How to Eat Sushi

by The Awl

How did they find some guy who’d never eaten sushi before? Anyway, there’s always more to learn.

Previously: should we even eat sushi?

New York City, May 7, 2015

★★★★ The warmth in the sun and the coolness in the shade lay in a balance not banal but equitable and wise. Tulip stems stood up like yardsticks; the sky was cloudless, stained around the edge. The forecourt was tranquil for the mad dash to retrieve the forgotten piano music in the middle of the viola lesson. The late-day colors were bright and clear. Sunglasses rode tucked in collar. Hair blew around gently. Little blinding bursts of light arrived from all directions.

Graceland Deferred

by Tyler Gillespie

At a stoplight in Memphis, seven hours after leaving New Orleans, my roommate and I idled next to a nineties-style, three-windowed white limousine with Elvis Presley’s profile outlined on its side door. The King’s face pointed toward a small, blue wall lined with silver block letters that spelled out Elvis Presley Boulevard, the street’s official name since 1971. On the corner stood a visitor’s center, which looked more like a bowling alley than any type of official state building. The boulevard stretched on in the distance, parallel lines of fast food joints and car dealerships, until we saw the Heartbreak Hotel. After the Presley-faced limo sped into away, we drove by the singer’s former home, which was closed for the evening. But we weren’t disappointed: The next morning, we were going to Graceland.

In the late eighties, Paul Simon sang, “I’m going to Graceland / For reasons I cannot explain.” He’s not the only one. Each year, nearly six hundred thousand Elvis fans buy tickets to tour the grounds where the King is buried. The property, a 13.8-acre estate, with a twenty-three room mansion, racquetball court, a car museum, and an archives studio, was purchased in 1957 for reportedly just over a hundred thousand dollars. Twenty years later, at the age of forty-two, Presley died there; his then-fiancee Ginger Alden found him unconscious on the bathroom floor. After his death, relatives, like his aunt, moved into Graceland, and five years later, his ex-wife Priscilla opened it up for public tours. In 1993, his daughter, Lisa Marie, inherited the property, which is now a designated National Historic Landmark.

A day at Graceland can cost almost as much as one at Disney World. Tours start at thirty-six dollars and run as high as seventy-seven. Each package comes with a self-guided iPad tour narrated by Full House’s own rocker-uncle John Stamos. After my roommate and I discussed our options, we landed on the forty-five-dollar platinum tour package, which included access to Presley’s airplane collection and an “Archive Experience,” basically a presentation of rare artifacts from the vaults, given by an actual human. The mid-price package sadly meant we’d forgo “front-of-the-line mansion access,” but we wanted to save money for souvenirs.

On a recent first date, a guy told me he owned an Elvis cookbook. “Elvis loved pie,” he said. “The book contained some of his favorite recipes.” While there was no follow-up date, his Presley fandom lead me to some of the weirder fan merchandise. An Ebay search for “Elvis” returned nearly two hundred thousand hits: a commemorative pocket knife, a G.I. Blues Christmas teddy bear set, and Sun Studio collector’s plates galore. Presley is printed on money, stamps, patches, magazines, and photo albums. His image is on items ranging from beach towels to a Monopoly board to a homemade-looking piece of “clay art” selling for eighty dollars. When I told my mom about my Graceland plans, she asked me to buy her Elvis-themed salt-and-pepper shakers. I hoped to find them at “Graceland Crossing,” a Presley shopping center we passed before we turned into the parking lot of our hotel, the Days Inn at Graceland.

Lit up by a neon guitar near the entrance, the hotel’s lobby was a shrine to Presley mania: Mock-gold records lined the walls, while a statue, mouth open, mid-song, stood next to a wood table cluttered by framed photos of him. A giant portrait, the most handsome image in the lobby, hung behind the counter to greet visitors, while a white bust kept the front desk worker company. I paid for our sixty-five-dollar room and walked by a poster board covered in purple flowers to commemorate Presley’s recent eightieth birthday. From our balcony, I could see the guitar-shaped pool in the courtyard, and what I am pretty sure was one of Presley’s old planes, permanently grounded next to the Heartbreak Hotel. By the pool was a mural of Las Vegas, where Presley played residences, wed Priscilla, and now marries couples for about two hundred dollars.

Before I crawled into bed, I studied the room’s photos of Presley at different phases of his life. In Presley canon, his career changes are often placed in four shorthand categories: the early “Hound Dog” years; the movie years (he made thirty-one films); the concert years (signaled by the 1968 television broadcast of Elvis, widely known asthe ’68 Comeback Special because it marked Presley’s return from a ten-year performing hiatus); and the “Viva Las Vegas” jumpsuit years. In one of my room’s photos, he wears a uniform to commemorate his years of service in the army. In another, he’s decked out in a white jump suit, grabbing a microphone stand. Next to it was a photo of him lounging in a Hawaiian shirt; this Elvis watched over me as I drifted off to sleep.

I had wanted to find an Elvis impersonator — who greatly prefer being called “Elvis Tribute Artists” — but a hotel worker told us we’d come during the “off season.” There are an estimated eighty-five thousand ETAs around the world, but apparently, none live in Memphis full-time. During “the season,” she said, which coincides with Elvis Week, a ten-day celebration in mid-August, flyers for ETA performances clutter the hotel lobby’s windows as competitive ETAs flock to the city to compete in the “Ultimate Elvis Tribute Artist Contest” to win twenty thousand dollars, a contract to perform with Legends in Concert, and the distinction of being the “best representation of the legacy of Elvis Presley.” To qualify, an impersonator must win a preliminary round held at one of nineteen earlier competitions sanctioned by Elvis Presley Enterprises — an organization created by “The Elvis Presley Trust” to handle official Presley and Graceland business — which take place in cities like Presley’s birthplace of Tupelo, Mississippi, Ontario, Canada and Lancashire, England.

With so many ETAs out there, only a select few can make a living off of the craft. In 2012, thirty-year-old Victor Trevino, Jr., placed second in the big competition, which scores contenders based on their vocals (forty percent), style (twenty percent), stagewear (twenty percent) and presence (twenty percent). In a YouTube clip from that year’s performance, Trevino walks on stage to screaming fans, wearing a fifteen-hundred-dollar gold jacket. Before he starts singing “It’s Now or Never,” he smirks, perfectly mimicking Presley’s half-lip curl. When he sings, his voice hits a similar treble and vibrato that matches the King’s later vocal stylings; if you close your eyes, you almost forget how young Trevino is. As a full-time tribute artist since 2007, he’s performed internationally in countries such as Sweden and Spain, where he did a week-run of a show that portrays Presley’s different eras. “They really like the shows in foreign countries,” he told me. “He never really got to do any full-blown concerts in foreign countries.” On Gigmasters.com, a booking site for impersonators, his rates now range from two hundred and fifty to twenty-five hundred dollars per hour.

When Trevino was in college, someone suggested he start performing as Elvis. He eventually competed in a Legends concert in Branson, Missouri, where he was scouted by managers who booked him for Elvis Lives, a touring show formatted as a “musical journey” of Presley’s career from the earliest Sun Studios years to the ’68 Comeback Special. The iconic black leather suit of the Comeback Special is most comfortable for Trevino to portray, because of his youthful look. He told me that a respectful tribute artist knows how to have an authentic characteron stage; he also doesn’t “particularly like” the way he looks in a jumpsuit, Presley’s iconic later-career uniform. “There’s some people who constantly think they’re Elvis,” he said. “It’s the weirdest thing. I don’t care for those kind of people.”

Along with Elvis Lives and Legends, Trevino also occasionally stars in a show called “A Night to Remember,” which pays homage to the Million Dollar Quartet, a 1956 Presley jam session which included Johnny Cash. The impromptu set was recorded by Jack Clement, who, Trevino says, asked him to record original music when they performed together in Europe. While he never followed up with Clement, who died in 2013, Trevino still works on some of his own music. Mostly though, he wants to honor the King’s legacy. “Elvis wasn’t the first rock ’n’ roller, but he was the most important,” he said. “His music not only changed America, it changed the world.”

The day after arriving in Memphis, I woke up early to hit the continental breakfast. As I made my way to the free eggs and waffles, I noticed small ice patches. “How charming,” I thought, “there’s a little bit of snow on the ground.” At the breakfast nook, I grabbed coffee and sat at a table with fifteen other Elvis early-birds, older people who wore mostly white t-shirts and talked quietly amongst themselves. Their eyes slowly began gravitating toward the TV. A newscaster was announcing that schools and businesses would shut down for the winter weather. “They’d never close Graceland,” I thought. “That’d be just so wrong and un-American.”

One of the other breakfast eaters, who sat beside a cardboard cut-out of a young Presley, called Graceland. Then, she delivered the bad news. It had shut down for the day. “We came all the way from Winnipeg,” a woman at a nearby table said. We had started breakfast as strangers, but now we bonded through our grief. In Februarys, the mansion is closed on Tuesdays, and the weatherman predicted worse weather for Wednesday. “Graceland may be closed for weeks,” one of my fellow breakfast mourners said. “We may never get to see it.”

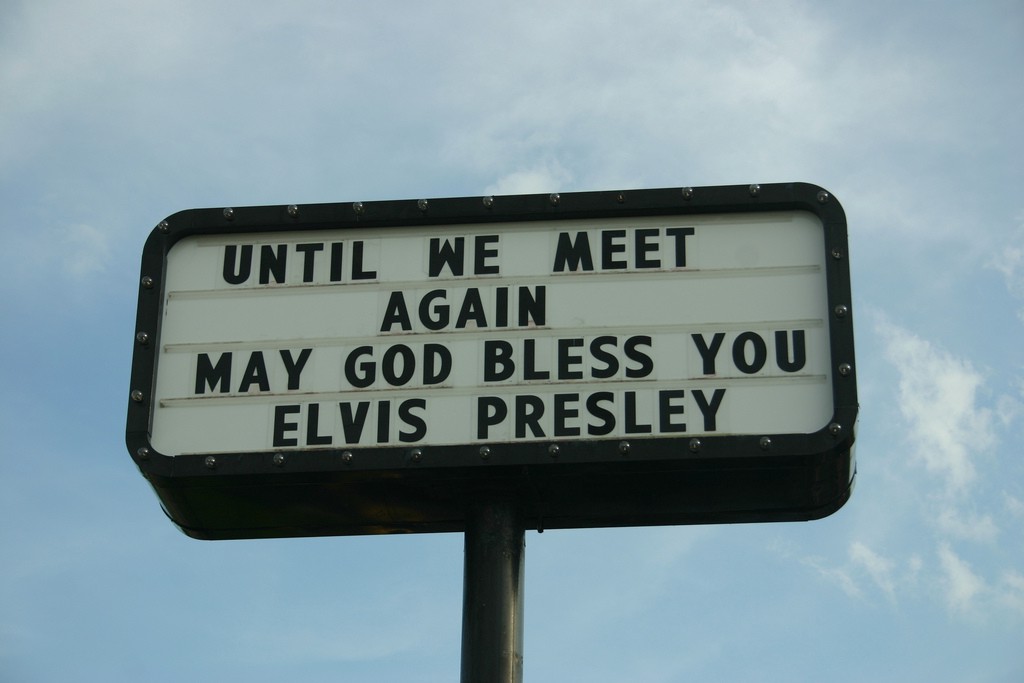

My roommate and I took the next hour or two to process our feelings. We’d be denied entrance into the famous, music-note iron gates. We wouldn’t step foot onto his racquet ball court. We couldn’t walk among his hall of gold records.We’d miss out on the airplane tour and the automobile museum and all his archives. No jumpsuits. Dejected, we decided to cancel the rest of our trip. We didn’t have the time or money to wait out the winter storm, so, only one day after we arrived in Memphis, we scraped ice from the car’s windshield and prepared for the drive back to New Orleans. After I stepped over some ice, I looked up at the Days Inn road sign which read: Until We Meet Again May God Bless You, Elvis Presley.“At the very least we can have some retail therapy at a souvenir shop,” I said as we drove away from the hotel. “I want to buy it all.” There are probably ten Elvis-themed shops on Elvis Boulevard, but they were all closed, too.

Three days later, in New Orleans, after I recounted my failed Graceland endeavors, a friend mentioned the Krewe of the Rolling Elvi, a group of men who dress up as Elvis and ride scooters in a Mardi Gras parade. I’d seen them roll the previous year and remembered their sparkly jumpsuits, Elvis wigs, and sunglasses. They had ridden glowing bikes through a line of outstretched hands. This year, the Krewe counted a hundred and nineteen “rolling members” and thirty-five “Memphis Mafia,” guys who were basically auditioning for full-fledged membership in the Krewe. There were also twenty-five Priscillas, a “lady’s auxiliary” who wore big buns to resemble the King’s ex-wife. Graceland may be the epicenter of the Presley universe, but his fans live everywhere.

On the Friday after Mardis Gras, I walked to a crawfish boil to meet the thirty-one-year-old Krewe captain Tim Clements. While he chatted with some people, I noticed how he looked strikingly like the sixties, Elvis is Back!-album Presley. Though his Gmail icon had shown him in full Presley gear, I hadn’t expected such as strong resemblance — he could pass as the King’s distant cousin, except that he speaks with an unmistakably New Orleans who dat drawl. “When you see a group of Elvi riding their scooters,” he said, between bites of the season’s first crawfish batch, “it’s the coolest thing in the world.”

As a kid, Clement’s sister listened to New Kids on the Block, but he played Presley songs like “Return to Sender” and “Teddy Bear.” In 2007, he first witnessed the Rolling Elvi — a term, he says, is the grammatically correct plural of “Elvis” — a sighting which proved monumental. “It was the greatest frickin’ thing I’d ever seen in my life,” he said. “If there’s anything I love more than Elvis, it’s Mardis Gras, so the Krewe was made for me.” But it wasn’t easy for him to join the organization; they wouldn’t return his emails. One day, he noticed a guy wearing a Rolling Elvi shirt, and the guy told him about an annual Presley death-day party that many Krewe members attend. Clements dressed in a jumpsuit and hopped on his Vespa to hit up the party. He hounded the Krewe until they let him in, mostly, he says, because he naturally had “the sideburns” to go with the costume.

Before he joined in 2009, the Krewe mostly met on Presley’s birthday and death-day parties. In costume, they all introduced themselves as Elvis, so they didn’t really know each other. He decided to organize different functions and at these events, he says, he’d see members for the first time “without their sunglasses or hair.” As the organization grew, charities asked members to perform at events. Eight or ten guys, he says, now make regular appearances. There’s even a section of the Krewe called “The Jailhouse Rockers,” which works on their dance steps for these functions.

But Mardis Gras remains the biggest event of the season. They ride in the massive Krewe of Muses parade, which features over one thousand riding members and the all-female Muses. In 2011, Clements, dressed in full-on Presley gear, and re-created his wedding proposal during the parade. He had a blinking ring for a throw (items members toss from floats), and he gave his wife one “to put next to her real ring.” It was also the first year, he says, his scooter did not break down during the ride.

Before I left the boil, Clements told me to check out Clockwork Elvis, fronted by a man he considers the “hands-down best” Presley singer in New Orleans. The band happened to be playing a gig at a bar within walking distance of my house, so a few hours later, I went and listened to Clockwork Elvis’s funkified rendition of “Hound Dog.” The voice was as good as Clements said; it sounded like an updated version of Presley, confident and raspy, yet somehow still melodic. Multi-colored Christmas lights hung from the ceiling to help light the stage as the band played Presley songs in alphabetical order (their choice to organize the night’s set). About twenty people, a few more than who’d earlier mourned with me when Graceland closed, convened with the King’s spirit at the eccentric neighborhood bar. A gray-haired man in a button-up shirt bobbed his head in a corner booth. A college couple drank Coronas while a tipsy woman, feeling the music, shakily danced.

Clockwork Elvis formed back in 2001 at the suggestion of a bar owner who wanted an Elvis band to play at his parties. While the band had kind of started as a joke, they realized they had fun playing together, and, after a few solid shows, people asked them to perform at different functions, like an all-expenses-paid trip to play at a wedding in Hawaii. (The couple, however, separated less than two weeks before their nuptials.) After a few years of being called “The Elvis Band,” they changed to their current name to avoid becoming “just be another tribute band.” The band decided to juxtapose Presley with Alex DeLarge from Clockwork Orange to show how both were “fictional characters” in their own right; their lead singer DC Harbold now regularly wears a Clockwork hat.

During the band’s set break, Harbold smoked a cigarette at the bar. I told him I’d just come from Memphis, but I couldn’t bring myself to mention that we didn’t make it into Graceland. When most people think of Presley, they imagine rhinestones, over the top costumes, sideburns, rambling, and scarf-throwing. But Harbold, who manages No Fun, a comic book store, by day, wears jeans and a short-sleeve shirt. At times, he sings with a cigarette loosely hanging from his lips. The exaggeration of impersonators, he says, has more to do with the iconography of American pop culture than the musician. “We’ve lionized Elvis and canonized him to the point of being a twentieth century American Jesus,” he said. “Elvis was a real person who grew up just like the rest of us, but had a talent and was in the right place at the right time.”

Harbold says that Presley’s legacy is music that’s “young, dangerous, sexual, and unexpected,” but people expect the over-affectation of Elvis. He thinks that it’s a “mockery” for people to just associate Presley with wardrobe. “He liked dressing up and liked cool suits,” he said, “but the bulk of his career had nothing to do with jumpsuits.” Still, he admits that the get-ups are more fun to wear, because “guys love wearing onesies, man.”

While Clockwork Elvis played a country-meets-soul version of “G.I. Blues,” my favorite song from the movie of the same name, I realized I was glad my trip to Graceland didn’t work out: I wouldn’t have heard this if I had made it to the mansion. Though he died thirty-seven years ago, Presley’s fans keep him alive. As Harbold belted out the “G.I. Blue’s” lyric, “We’d like to be heroes, but all we do here is march,” I thought about Presley’s small-town, Mississippi roots. He could have never dreamed people would portray him for a living — his legacy is some type of great, hallucinatory American Dream, and it seems like we won’t be waking up from it anytime soon.

Photos by Betsy Weber, Mark Stephenson, Kees Wielemaker, and Dudley B. Batchelor, Jr., via Flickr Creative Commons

Things To Have Named After You, In Order Of Difficulty

by Eric Spiegelman

51. a Wi-Fi network

50. a star

49. an online publication

48. your son

47. your daughter

46. your company

45. your band

44. an autobiography

43. a public square in Los Angeles

42. a burger, drink, salad or sandwich at a Los Angeles restaurant

41. a scholarship

40. an award

39. a folly

38. a lunar crater

37. a hospital wing

36. a biography

35. a public park

34. a library

33. a high school

32. an expressway

31. an airport

30. a disease

29. a television series

28. a steamboat

27. a sports move

26. a generic item of clothing

25. fauna

24. flora

23. a comet

22. a musical instrument

21. a weapon

20. a medical procedure

19. a part of the human body

18. a public square in a European city

17. an “ism”

16. an adjective

15. a mountain

14. a bay

13. a river

12. a public holiday

11. an adage

10. a theorem

9. a law of physics

8. a unit of measurement

7. a chess opening

6. a slang word for money

5. a disreputable profession

4. a dynasty

3. a religious sect

2. a city

1. a month

Photo of Rosetta, a comet, courtesy of the European Space Agency

The Beautiful Annihilations Of Yesteryear

“Reminding myself that the anxious, muddled present is just one of an infinite number of unlikely outcomes for the planet turns out to be a pleasant way to drift off to sleep. I find the most apocalyptic episodes to be the most therapeutic, especially when they end, as they often do, with jokes. Hearing jagged fragments of today’s news and culture in any of the shows’ thousand may-be worlds affirms the value of vigorously imagining the worst: The stories that worry most vividly are the ones that have aged best.”

— It’s funny because it’s true.

A$AP Rocky, "Everyday"

Rod Stewart, Miguel and Mark Ronson: this is the musical equivalent of stunt-casting. And it works!

How to Catch Up on TV Over the Weekend

by Logan Sachon

This post is brought to you by Hulu. Sit back and catch up on all of the shows featured in this post and more on Hulu ahead of the season finales!

My brother and I each took turns living at home as adults.

Our gap years in adulthood came a few years apart, but they both had a few things in common: 5 p.m. happy hours on the porch with my parents (they are retired, and very good at it); rude weekend wake ups from my dad when he’d decided we’d slept too long; and rollicking family nights around the TV watching The Voice.

Have you ever watched The Voice? It’s great, especially when you watch with your parents. I cannot recommend it enough. We’ve all become experts at performance and presentation. My mom has watched it so much that she is now basically a world-class vocal critic and knows what each judge will say before he says it. It is incredible. Because of The Voice, I have only ever felt deep affection for Adam Levine and will listen to otherwise unlistenable songs on modern country radio just in case it is Blake Shelton singing.

But: It seems The Voice comes on practically every night of the week, so no, I don’t watch it live now that someone isn’t fixing me snacks and pouring me wine each Monday and Tuesday at 8/7 central. (Now I catch up on all missed episodes on Hulu.) But it’s still something special that our family shares. I call my mom and she gives me the play-by-play on what happened, who did well, which performances I absolutely have to see and then every few weeks I catch up and call her, wanting praise for catching up, and she’s like, not really impressed. But it’s work, catching up on TV. It takes stamina, it takes planning. And I’ve perfected it.

As a person who watches The Voice, The Blacklist, Dancing With the Stars and all other TV exclusively in marathon watch sessions, here is my personal guide to watching a lot of TV in a long sitting. (Maybe it’s weird to present a TV watching guide right as spring is about to get sprung. But don’t worry! We’ve got like, two weeks max before it gets disgusting outside again and we have to stay in bed in front of the air conditioner.)

My two favorite times to marathon TV are Friday night or Saturday day, or preferably, perfectly, both.

Friday Night

Catching up on Friday night is fantastic. Fridays are a horrible time to go out and be with people. All I ever want to do on Friday is be alone. If you want to attempt this method, simply say no to everyone who asks you to do anything and then rush home after work and order takeout and open a bottle of wine and sit on the couch eating takeout and drinking wine and catching up on your favorite shows and that is it. That’s the guide for that. Maybe have a second bottle of wine on hand; I don’t know your life.

Watch until you pass out or are sick of watching, which sometimes never happens! The only sunrises I see are when I’ve stayed up all night watching TV.

Saturday Day

If you’re spending your Saturday watching TV, the key is to start early. Set your alarm for an hour after you normally wake up, give yourself a little cushion there, a little treat. The alarm will go off and you’ll be like, “WHAT I THOUGHT IT WAS SATURDAY,” and then you’ll remember, “Oh, it is Saturday.” Then you will be happy and energized enough to get out of bed and make some tea or coffee and then head to the couch or back in bed. (If you don’t have a TV in your bedroom but are a Hulu subscriber, you can stream all of your favorite shows from your mobile devices.)

A bagel and a latte while you catch up on your shows might sound like a good idea, but I’m going to advise against it. Don’t go outside. You should probably avoid the windows, too. You will see people out in the world and you will wonder if you should be out in the world, too. Nope! You can go out in the world tomorrow. Tonight, even. But not today. Today is for TV.

So. You’re in your house. The shutters are drawn. Scrounge some food for breakfast. Leftovers are good Saturday morning TV-watching breakfast. Cold Thai food is pretty great if you’ve got it. Or maybe you’ve got cereal, that’s nice. Don’t cook anything, God no. Lethargy is the goal of this day, no sudden moves. If you cook eggs, which is work, you’ll have to do the dishes, which is more work. Or you won’t do the dishes, and then you’ll be thinking of them all day instead of what you should be thinking about, which is TV. I’m getting stressed out just thinking about it! No cooking. No dishes. Get comfortable. Start watching. Then, once it’s noon, you can think: “It’s only noon, and look what I’ve accomplished! I’ve already watched so many episodes! To think I could be sleeping! This feels great.”

When you get hungry, you can order lunch, which might be a little bit hard. A lot of the best and classic takeout is not available at noon on a Saturday. This is actually a real problem for me, because I want to eat Indian and Thai food at all times, but it is not available at all times. Maybe you can hold out on eating until 4 p.m. when chicken korma and papri chaat are available. Sometimes I can. If not, hamburgers are nice. Hard to mess up a hamburger. Fries. Ask for extra ketchup, learn from my mistakes. Maybe get a deli smoothie, a deli salad, for health. Deli chicken fingers. Lots of options. Don’t despair. Or maybe you have food in your house. What is that like? Eat some of it. But remember: no cooking. No dishes.

After you eat your food, it’s getting to be time to be aware of your deadline, the time when you have to leave to do whatever you’re doing, you know, like, out in the world. Do you have time to watch another episode? Do you really?

Friday Night and Saturday Day

This is the real deal. This is how you do it. I’d take a Friday night/Saturday day combo once a month over more frequent viewings every time. What a joy, the Friday night/ Saturday day combo is. With real indulgence comes real accomplishment.

Friday night goes exactly like it would if you were not also planning to spend all of Saturday watching TV, except you need to double up your supplies. Buy two (or three) bottles of wine. Order double the amount of takeout. “But I can just order more takeout tomorrow,” you might say. That’s not always true. What have we learned about the availability of premium ethnic foods during the daytime? Be prepared for anything. Order an extra thing of drunken noodles, another thing of fried rice, a chicken tikki. Go wild. “I just spent $40 on takeout for one person,” you might think. “That seems excessive.” It’s like ten meals. It’s fine.

So: Friday you eat half the takeout and drink half the wine. Don’t kill yourself staying up all night. Or do. If you do stay up, let yourself wakeup naturally. If you go to bed early (“early”), set that alarm. Don’t sleep through your TV time! You only live once, make sure you’re spending it watching other people’s lives on a small (or really small) screen. Wake up, watch an ep. Breakfast is cold takeout, perfect. Lunch, more cold takeout. Or maybe microwave it, be gourmet, you foodie! Two p.m. is a good time to start drinking wine on a weekend, uncork it. Do you still have takeout? Just keep eating it all day, why not.

When it’s time to go, go. If you haven’t finished, you need to be spending more time watching TV. More frequent marathons, that is my prescription. See a friend. Ask them how their day was. They probably did a lot. Smile and nod. And what’d you do? You watched TV. Say it loud, say it proud. Don’t say you read, don’t say you worked out or worked or did chores. You had a great time. You watched TV, and you watched it right.

New York City, May 6, 2015

★★★★ The gray morning was gentle on the eyes and cool like damp concrete. Petals and maybe a raindrop blew on the breeze. People were still out in cutoffs. Intermittent sun would appear, allowing them to justify the decision. It was hard to tell the film-crew members from the people staring at the film crew from the people who were just standing around out in the air. There was blue and white in the rush-hour sky, and then uptown it was totally and disorientingly clear and blue, with the late light flowing over everything and the Park a bright green little door at the end of the long narrow corridor of the shadowed crosstown blocks. Sun passed through the depths of the monkfish cheeks, lifted out of their pan on the spatula, till the last traces of translucent pink were gone.

Where Will WeWork?

by Brendan O’Connor

In December, the Wall Street Journal reported that coworking startup WeWork had leased around 1.6 million square feet of office space in New York. This made it the fastest-growing company by footprint in New York since 2010. In the months since then, WeWork has added nearly another half-million square feet.

“We take large spaces and cut them up into smaller spaces,” WeWork co-founder and CEO Adam Neumann said in a TechCrunch Disrupt Q&A from earlier this week. The business is much more complicated than that, of course: It offers free beer at all of its spaces; there are couches, where people from all walks of life (who are members of WeWork) can talk to each other; and there’s an app, a kind-of social network for members. In December, the four-year old WeWork closed a $355 million funding round at a $5 billion valuation.

“It’s almost like you’re a real estate company wrapped in this tech sheen,” Bloomberg Television’s Betty Liu pointed out in an interview with Neumann and early WeWork investor Mort Zuckerman, of Boston Properties, in February. “There is no real estate company that can become worth five billion dollars in four years,” Neumann demurred. In other interviews, Neumann emphasizes the WeWork app as much as the WeWork space itself. “We don’t have tenants, we have members. It’s a month-to-month licensing agreement, we’re not actually looking for long-term commitment,” he said.

Whether WeWork is looking for a long-term commitment from its members or not remains to be seen, but they have certainly made one — several, actually — to landlords in the city. (WeWork did not respond to requests for an interview.)

According to a survey of recently signed leases in Downtown Manhattan by a NYC commercial brokerage firm, in February, WeWork signed a new, sixteen-year lease at 85 Broad Street, in the Financial District, for 233,174 square feet across six floors. WeWork is paying approximately $5.1 million per year for the lower three floors, at $44 per square foot, and approximately $5.7 million per year for the upper three floors, at $49 per square foot; cumulatively, WeWork is paying somewhere around $11 million per year in rent for the next five years. (It goes up after that.) Average rent in the area was $56.94 per square foot at the end of March, according to market analysis by CBRE, so market rate for this amount of space would be closer to $13 million. In other words, WeWork is getting a pretty good deal. (It is also getting the first fourteen months for free.)

A couple of months later, in April, WeWork signed a nineteen-year lease for the entire fourth through seventeenth floors — 180,000 square feet — of 1460 Broadway in Midtown. The same day, WeWork signed a fifteen-year lease for 140,169 square feet — all nine floors — at 315 West 36th Street in Midtown West.

The more conventional real estate world admires WeWork’s rapid rise, but scoffs at its pretensions to being something other than it is. “It’s not original in concept: they’re executive suites. They’ve built on everyone else’s successes, and taken it a step further,” Jeff Nissani, a commercial broker at Marcus & Millichap, told me. Asked what their impact on the market has been, Nissani deemphasized WeWorks effect on rent rates. “Their impact is that it’s very difficult for other executive suites to compete. Because they’ve capitalized so well, they can offer a much higher-end build-out.” And, in turn, they can charge more for the space they provide: According to WeWork’s website, tenants at the space on Broad Street will pay from $750 per month for a one-person private office to $3,900 per month for a six-person private office.

So far in New York, WeWork has fifteen locations in Manhattan and one “coming soon” in DUMBO. (In November, Forbes confirmed reports that WeWork would be the anchor tenant of a $300 million redevelopment in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, of which Boston Properties is a co-owner; it will have some 200,000 square feet of space there.) The Brooklyn market is ripe for the taking: “The demand for small office spaces is the highest it’s ever been in the history of the borough,” Christopher Havens, vice president of aptsandlofts.com’s commercial division, told me. “When tenants call me looking for office space for one or two people, I say the chances are infinitesimal that they’re going to find something. People just don’t build offices that small. There are a lot of illegal subdivisions along the L train, east of the highway. But I tell clients, ‘Go to a coworking space.’”

“The demand for small office spaces in Brooklyn is not physically satisfiable — not without new construction,” Havens continued. “[WeWork] won’t ‘have an impact.’ They’re fulfilling a need — a desperate need. There’s no space.”

Neumann, who serves as the company’s public face, grew up on a kibbutz. “A kibbutz is a failed social experiment that happened in Israel,” he says in a video from a Q&A at this year’s TechCrunch Disrupt. The major flaw with the kibbutz Neumann grew up on, he says, is that everyone made the same amount of money. WeWork, he says, is a “capitalist kibbutz.” “One the one hand: community. On the other, still, you eat what you kill.”

The community that WeWork imagines itself providing is one from and through which capital flows, but it is also one in which people help each other out of the goodness of their hearts. “When Hurricane Sandy hit, our members were helping each other, some people had power and some people didn’t,” Neumann says. “That was the first time I saw our community really alive.” (Sharing economy start-ups in New York City love talking about Hurricane Sandy.)

“The world is changing. You have a generation that cherishes intention and meaning, a lot of times above material goods,” Neumann says. “We like to believe that anybody in the world who understands the sharing economy, who defines success not just as financial but also as feeling good, treating other people well, and just being grateful understands that by leveraging the sharing economy he or she can get space, cars, bikes, hotels — not only at a discounted rate, but through leveraging the sharing economy through a much more social experiences.” He continues, “Anybody who gets that is part of ‘the We Generation.’ It’s not limited by age.”

It is a convenient idea, this “We Generation.” It refers to a category of people united across all boundaries — space time, race, class, gender — by the illusory notion that we are all working and living for each other, and that somehow this notion is inherently compatible with the demands of investors, the market, and capitalism. The logical conclusion of WeWork’s vision is to expand into the residential market — to break down the boundaries between residential and commercial. This is already happening: landlord and developer Vornado Realty Trust is redeveloping a building for WeWork in Washington, D.C.’s Crystal City neighborhood that will include both residential and office space. “Landlords briefed by WeWork on the concept liken it to a dorm for Millennials in their 20s,” the Wall Street Journal reported. WeWork wants to control the space in which every significant aspect of a certain kind of person’s — the We Generation’s — life takes place.

One employee, who requested anonymity because talking to the press about WeLive is expressly forbidden by the company — “a higher up who did so was half-jokingly publicly shamed at the corporate summit” — told me, “They see themselves as Uber for space.” This person added, “They want to destroy the work-life barrier.” Imagine: You are a WeWork member, a graphic designer, maybe, or a serial entrepreneur. You have friends and colleagues and clients — what’s the difference, really — all over the country, or maybe even the world, and you can travel between WeWork’s residential office spaces to see them all for a few days, weeks, or months at a time, without ever leaving the comfort of your coworking home. Wherever you go, there We are. Living. Working. Weing.

In the Bloomberg Television interview, Zuckerman made it clear that he doesn’t think WeWork getting into residential is the best idea. Neumann is “the master of this new kind of office space,” Zuckerman said. “I would concentrate on that.” Then, he added, “When he has grey hair, then tell him to move into residential.” Neumann just smiled in response.

Internally, while there is some skepticism that the WeLive project is possible, there’s also the whole-hearted belief that if anyone can do it, Neumann can. “If you’re ever stumped for conversation you can just talk about how great Adam is,” the employee said. “Yesterday, people put wigs on for his birthday, to wish him a happy birthday.”

Photo by Payton Chung

Correction: This piece previously stated some of WeWork’s yearly rates as monthly. We regret the error.