B.B. King, 1925-2015

“B. B. King, whose world-weary voice and wailing guitar lifted him from the cotton fields of Mississippi to a global stage and the apex of American blues, died Thursday in Las Vegas. He was 89.”

New York City, May 13, 2015

★★★★★ The leaves below, now thickly massed, heaved in the breeze. Cool air blew in over bare toes; music carried up and in. Out on the downtown sidewalk the ends of a man’s skinny red necktie separated at right angles. Green treeshade lay under cloudshade. Up on the office roof, the wind seemed to be blowing dry dirt out of the planters onto the white cushions of the furniture. Two downy little squabs huddled together on the guano-spattered windowsill of the next building. The taxi crosstown passed a playground; a paper airplane speared up past the top of the high chain-link fence. The roof now where the cocktails were came with an immense portion of sky, blues and grays and whites. A little bird crossed the deck like a feathered bullet. To the south the clouds were somber and glow-cut. That it was too cold up in the open was a personal failing, a momentary idiocy committed walking past the coat closet hours before, nothing to be held against this enlarged and long-lasting day or its air currents. The brownies were warm. Ice lingered in a cup of rye. The brisk air bore away cigarette smoke, nicotine vapor, marijuana vapor. The wood stove was lit, paper spreading to kindling to high-piled chunks, till in no time at all the denim in the fireward leg of the jeans was alarmingly hot. A burning end of wood fell out onto the floor and had to be returned. The cabbie afterward kept his window open and smoked in retaliation for having to take a fare uptown.

The Academic Behind the Media's 'Transgender Tipping Point'

by Nicole Pasulka

While Bruce Jenner often looked like the pushover of the Kardashian clan, in reality, he told Diane Sawyer last month, “I had the story.” Over four hundred and twenty-five episodes of reality TV, “the one thing that could really make a difference in people’s lives was right here, in my soul,” Jenner said. “And I could not tell that story.” Until he did. In a moment that Time magazine has dubbed the “transgender tipping point,” the Jenner interview is only the most recent and high-profile example of the media’s growing fascination with the stories of transgender people.

Behind the scenes for the Jenner interview, the show Transparent, and the Time magazine article is Susan Stryker, a professor of gender and women’s studies at the University of Arizona, and the author of several books on transgender history, who has been giving interviews about trans issues for twenty years. These days, she asks journalists why they’re approaching trans stories “as some weird thing you’ve never heard of,” when according to one survey, nearly ninety-one percent of people in the United States are familiar with the term “transgender” and three-quarters of them can define it correctly.

The other day, I talked with Stryker about consulting on the Jenner interview, how media attention to trans stories has changed in recent years, and what all this visibility means for the future of trans rights.

There has been a remarkable surge in media interest when it comes to trans people and their stories. Why do you think this is happening?

First, there has been a persistent drumbeat of activism on this topic since the early nineteen nineties, like a trickle of water running across a plain that eventually carves a canyon. Second, the landscape really changed in the United States after the repeal of the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy on gay and lesbian military service and the Supreme Court decisions on marriage equality. Transgender issues were suddenly positioned as the “next big thing” in a civil rights progress narrative.

Third, thanks to our contemporary biomedical and communications environments, it’s simply not as difficult for most people to accept that our bodies and selves are radically transformable over time. Fourth, higher rates of migration, as well as higher levels of global media exposure, have made it easier for more people to see how sex, gender, sexuality, embodiment, and identity vary from place to place. Finally, kids today, ya know? Many of the so-called millennial and post-millennial generations accept that transgender phenomena are simply present in their world. No big.

It’s my understanding that you’re being asked by a lot of media organizations and journalists to talk about trans stories. Who’s calling and what do they want to know?

Last summer, I spent hours with Katy Steinmetz talking with her for what became the Time magazine cover story on the “transgender tipping point.” I’ve been in communication with the producers of the forthcoming Eddie Redmayne film, The Danish Girl, about the nineteen thirties transsexual Lili Elbe, to consult on questions of transgender representation and to strategize with them about how to head off sensationalistic media coverage in advance of the release. I’ve done two different “Room for Debate” opinion pieces for the New York Times on transgender-related topics, been in conversation with their editorial staff about the current series of editorials they are running on transgender issues, and worked closely with the producers of “Retro Reports” on a story about transgender history. I talked with Cosmopolitan magazine about how transgender issues might be pitched to their readership, perhaps focusing on relationships in which a partner transitions, and with The Advocate about the complexities of race, class, and transgender identity. As that tsunami of attention to trans issues was cresting, I spoke with NPR and the News Hour with Jim Lehrer here in the United States, and with the CBC in Canada. After the Bruce Jenner story broke, I talked with the Hollywood Reporter about whether the forthcoming reality show would be exploitative.

I’ve been asked to offer remedial level “Trans 101” information (“What’s the difference between gender identity and sexual orientation?”), help editors think about story lines, provide professional expertise on transgender history and politics, and give insider advice on how to finesse delicate questions of language, reception, and messaging.

When did you first start talking with media?

I first started talking to local LGBT media in San Francisco in the early nineties, and to national mainstream media by 1995, when the transgender movement rapidly expanded along with rise of the Internet and became more visible. My steady trickle of media engagement took an uptick around 2005, with the release of my historical documentary film Screaming Queens, about trans women banding together to resist police harassment at the Compton’s Cafeteria in San Francisco’s Tenderloin neighborhood in 1966. My filmmaking partner Victor Silverman and I spent a year on the festival circuit, had a national PBS broadcast in 2006 and did a lot of media to publicize the story, but had trouble breaking into the mainstream — transgender stories were still being treated as something that would appeal mostly to a small niche market.

I had other media exposure over the last few years related to my current work in higher education, especially about the transgender studies initiative I’ve been spearheading at the University of Arizona. But all of this pales in comparison to the recent onslaught of attention to transgender issues.

Could you talk about working with ABC News on the Bruce Jenner interview?

It was non-stop for a few weeks. All I knew at first was that Diane Sawyer was planning on doing a “big story” on transgender issues. After being sworn to secrecy, I learned that it was going to focus on Jenner. I worked closely with one of the associate producers on everything from what to read to prep Sawyer for the interview, sources for archival media, how questions should be framed, who to call on for talking-head commentary, and who might make good test-audience members. Of course, in the end they made their own decisions, regardless of what I suggested.

What did you think of the interview?

I thought the interview itself was OK. Jenner had the grace and wisdom to not act like her/his experience of being trans was definitive of other people’s experience. S/he was “relatable,” as they say, which is important in our media-saturated society. More significant for me than anything Jenner actually said was the opportunity the interview provided for reframing how trans issues should be approached in mass media.

How is the coverage of trans issues and stories changing?

What has seemed significantly different to me about the recent wave of attention is that the media professionals involved have the perception that this is a delicate topic with a potential for backlash, and that what sets us apart from other people needs to be handled with respect. They are very eager to “do the right thing,” even if they don’t know exactly what that is. And rather than asking non-transgender psychiatrists and surgeons and police officers or members of the clergy or representatives of some radical feminist fringe faction to please tell the world, “What do transgender people want?” they have turned to trans people themselves. We are increasingly seen as the go-to authority on our own lives.

So, if trans stories have been told for decades, Jenner’s story isn’t exactly new?

Taking the long historical view, both sports and the military — signifiers of a robust masculinity — have long been points of fascination and contrast in mass media stories about trans women. The “macho man becomes sex kitten” idea is irresistible catnip to media consumers. Back in the fifties, Christine Jorgensen, who was the first transsexual to receive huge mass media attention (bigger than Jenner today), was consistently framed as the “ex-GI who became a blonde beauty!” even though her military service consisted of being drafted after the end of combat in WWII, and serving ten months processing paperwork at Fort Dix, New Jersey. Twenty years later, transsexual tennis pro Renée Richards got similar treatment. Jenner is now being framed the same way: How could an Olympic athlete, this paragon of masculinity, consider himself to be a woman?

What impact do you think Bruce Jenner coming out will have?

It’s hard to say. It’s easy for me to be cynical given my historical knowledge stretching back more than a century, personal awareness of trans issues since my childhood in the sixties, and direct activist involvement since the nineties, I can feel that I’ve seen this all before and that media visibility alone is pretty inconsequential. All I can say is that I sense a difference in how journalists and mainstream media-makers feel they must represent the issues if they are to be accountable to the zeitgeist.

It’s my sense that many assume this coverage will lead to greater acceptance and rights. What is the relationship between visibility and policy changes or gains in legal rights?

Well, just ask yourself: even though major civil rights legislation addressing injustices experienced by racial minorities was passed more than fifty years ago, even though every schoolchild in the United States has likely heard the phrase “I have a dream” and has an image of King standing in front of the multitudes at the Lincoln Memorial, have we ended racism in this country? No. Media coverage at best amplifies the message that social change agents push for. It doesn’t make change in itself. As such, media visibility is only ever a part of a struggle, a means to the ends of struggles, and not the goal itself.

Most of the time I feel like it’s great that these stories are getting out there and people are more open and aware, but I wonder if there are some reasons to be wary of all this interest. Are you? Is there something we’re missing here?

We can’t be complacent and pretend that freedom has been won for entire categories of people just because there’s more positive mass media representation. While it’s great that some trans people can have job security, get passports, access health care, and not get hassled by the cops for walking down the streets, others can’t. Trans communities — never monolithic or homogeneous to begin with — are increasingly bifurcated into those kinds of trans people deemed worthy of respectability, acceptance, or tolerance, and those deemed unacceptable: people who don’t pass as non-transgender, poor people, people of color, people who do things that have been criminalized in order to have food to eat and a place to sleep. If only some trans people benefit more from “progress” on these issues, then that isn’t really progress at all.

There seems to be an assumption that after recent gains in gay marriage, trans issues are a natural next focus and all this coverage is somehow part of an evolution in awareness or acceptance. Do you think this accurate, or is something else going on?

I think there is a relationship between the success of the marriage equality campaign and the recent upsurge in attention to transgender issues. Much of this annoys me — as if, now that we’ve taken care of a more important issue, we can move on to less significant matters. Generally speaking, I’m not a fan of progress narratives. And I’m very suspicious of how transgender being the “next big thing” can serve interests other than those of transgender people.

How so?

Over the last decade or so, gay and lesbian human rights issues have been used to legitimate US foreign policy agendas — no foreign aid for some African country unless they stop criminalizing homosexuality, for example. As transgender becomes the “cutting edge” of human rights discourse, it’s not difficult to imagine scenarios that might have sounded improbable a few years ago. Like, should the EU ban immigration of Middle-Eastern and north Africa Muslims to Europe if their cultures can be labeled transphobic in contrast to the neoliberal western democracies?

What stories still aren’t being told?

I think the media is still largely focused on transition stories, the way there used to be a predominant focus on coming-out stories for coverage of lesbian and gay people. Even a show like Transparent, which has a fair amount of nuance, revolves around how the adult children of a trans person deal with the slow rollout of their parent’s new gender expression. But it’s not like the only thing transgender people do is change sex. We have whole lives. We face challenges related to being transgender that are not related to transitioning, and we do things with our lives that have nothing to do with being transgender. Where are those stories?

What about stories of older trans people who have lived many decades after transition? How can we understand trans people other than through the framework of medicalization? We don’t diagnose people as having homosexuality anymore, for example — why can’t we just say that some people have a need to express their genders differently than most other people do, and leave it at that? Why does that have to be socially sanctioned or recognized by calling it a disease or a syndrome or a psychological condition? I could go on and on, but maybe it’s best to let journalists and their audiences discover for themselves in the years ahead the seemingly infinite variety of stories that can have a “transgender angle.”

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

The Remodeling of Greenpoint

by Brendan O’Connor

1133 Manhattan Ave, N713

• $5,042 per month

• 2 bedrooms, 2 bathrooms

• Nearest subway: G train at Greenpoint Avenue

In 2005, the New York City Council rezoned much of north Brooklyn’s waterfront, which had, until that point, been a predominantly industrial area. “The rezoning,” the New York Times wrote that May, “would transform the long-crumbling waterfront into a residential neighborhood complete with 40-story luxury apartment buildings, shops and manicured recreation areas.” And so it has, at least in Williamsburg. To the north, Greenpoint has largely yet to feel the direct effects of that landmark plan. Over the course of the next ten years, however, that is all going to change: planned new construction will add eight thousand new apartments in the next decade, the New York Post reported in March.

On Tuesday, a tall white man wearing headphones and a t-shirt emblazoned with a black-and-white image of a young black child framed by the words, “Brooklyn Before Gentrification” walked past one of those buildings, found at 1133 Manhattan Avenue. In marketing materials, the building is referred to as “Eleven33.”

The developer, the Domain Cos., received fifty-seven million dollars in financing towards the eighty-million-dollar development project. “The property will be the first apartment tower in the neighborhood to tap tax credits and low cost debt allocated to developments that include affordable housing and remediate polluted land parcels,”

Crain’s reported in 2012

. “That financing strategy could be increasingly common as more sophisticated builders come to the neighborhood bordered by Newtown Creek, which is a Superfund site.” Nearly sixty thousand people applied for the two-hundred-and-ten-unit building’s hundred and five affordable apartments.

The building, which is quite large, has two entrances. Both are accessible to all residents, Katie Eckel, an agent with MNS, was quick to assure me. There is no distinction between the affordable units and the market-rate units, she said. “They’re all mixed in together.” Asked whether the presence of the affordable units changed the way the building was marketed, Eckel was emphatic. “Not at all,” she said. “People are just concerned with the location. If anything, the market-rate tenants are jealous.”

All tenants at 1133 Manhattan Avenue enjoy discounts at local businesses, like happy-hour specials and ten-to-fifteen percent off at restaurants, Christophe Tedjasukmana, another MNS agent, told me. The building offers Verizon FiOS and each apartment has a pantry in the kitchen. “There are really a lot of condo finishes,” Tedjasukmana said as Eckel sang the praises of the walk-in closet. “Everything a girl could want,” she said. “Or a gay,” Tedjasukmana added.

The building is about eighty percent occupied, Tedjasukmana said, and there are less than two dozen (market-rate) units left; at this point, only two-bedrooms are available. For tenants who sign before May 15th, MNS is offering a month-and-a-half of free rent and no broker’s fee. The views of the East River and Manhattan from the roof — and the northern penthouse terraces — are impressive and, for now, unimpeded. Eleven33 is not directly adjacent to the water, and future developments in the area will stand between the building and the river. “In a few years, it could be a problem,” Eckel said. “But, if you’re renting, you don’t care.”

17 Monitor Street, 5K

• $4,335 per month

• 1.5 bedrooms, 2 bathrooms

• Nearest subway: L train at Graham Avenue

In 2013, St. Cecilia’s Roman Catholic Church in Greenpoint signed over two buildings it owned — a shuttered school and a smaller building — to a developer on a forty-nine-year lease. According to the Real Deal, rent on the properties starts at 1.2 million dollars annually and rises to 3.2 million dollars in the forty-sixth year of the lease.

“The properties have an unhappy backstory, which isn’t the developers’ fault,” the Brooklyn Eagle wrote last April. “After the century-old school closed in 2008, recession put the kibosh on a plan to market the buildings. The pastor, Father James Krische, invited artists to use them — and drew an enthusiastic response.” The school hosted an average of ten film and video shoots every week, the Eagle reported, until two years later when St. Cecilia’s was merged with two other parishes and Father Krische was transferred. “The artists’ days on Monitor Street were over.”

Now, there are sixty-nine apartments in the old, nearly fifty-thousand-square-foot school building at 17 Monitor Street. Although renovations are not quite yet complete — the official move-in date is June 1st — at least one is occupied, and other tenants have negotiated a May 15th move-in. Deposits on twenty-one apartments have been accepted so far.

Many of the apartments occupy old classrooms, Moiz Malik, partner and CTO at Nooklyn, told me. All units come with built-in, Bluetooth enabled speakers. On the top floor, the apartments are lofted — the high ceilings reminiscent of an old basketball gym. In the basement, there is a yoga room. “It’s kinda funny,” Malik said. “Buddhist yoga in a Catholic school.”

110 Nassau Avenue, 3A

• $1,800 per month

• Studio

• ~400 square feet

• Nearest subway: G train at Nassau Avenue

A few blocks north of McCarren Park, an eighteen-hundred-dollar-per-month studio is about seven hundred dollars below market rate for an equivalent apartment in the area. “The landlord could easily be getting way more,” Lotfi Chortani, a broker and the owner of Target Realty Group, said. “But he’s not that kind of a landlord. He’s not greedy.” The studio is small: the current tenant’s bed occupies the width and most of the length of a closet-like space separated from the main living area.

Chortani went on: “He’s got the commercial tenant on the ground floor. He covers his mortgage, and that’s it.” Standing outside, he waved down Nassau Avenue towards Williamsburg’s glittering waterfront. “They used to dump garbage there,” Chortani, an immigrant from Tunisia whose wife grew up in Brooklyn, said. “They would find bodies!”

The current tenant is moving to California for graduate school, so, if you like, you can buy all of his stuff — two years’ worth — and the apartment will be furnished when you move in July 1st.

A Poem by Steve Healey

by Mark Bibbins, Editor

Lab Report

He had a face with two eyes and a mouth.

He was my boyfriend; I was his girlfriend.

We went to the same highschool in the suburbs.

He was into science, and I was part of science.

I had a face with two eyes and a mouth.

The human body was a conductor of electricity.

I was his boyfriend; he was my girlfriend.

The sun rose at the exact time predicted.

There were microscopic animals everywhere.

I had a job on the weekends washing dishes.

We hung out at the park near our highschool.

The sun set at the exact time predicted.

The trees divided the sky into a grid.

We carved our hands into the picnic table.

There was broken glass on the playground.

In Biology class we dissected fetuses.

I was part of science, divided into boyfriend.

Left-handed, amputated, beheaded.

Our homework was learning to be liars.

We dissected what had never been born.

We never saw the dust mites eating our skin.

Between us we had a vagina and a penis.

There was science in not being boy or girl.

I had a job on the weekends saying nothing.

Anyone can be beheaded and rebuilt.

Our homework was learning to be bionic.

“What’s wrong?” he’d always ask me.

Between us we had hypothesis and data.

“What’s wrong?” I’d always ask him.

Steve Healey’s two books of poems are 10 Mississippi and Earthling, both on Coffee House Press. His work has appeared in American Poetry Review, Boston Review, Denver Quarterly, Fence, jubilat, and in anthologies, most recently The New Census: an Anthology of Contemporary American Poetry.

You will find more poems here. You may contact the editor at poems@theawl.com.

New York City, May 12, 2015

★★★★ One more rainy-looking morning once more brightened and dispersed. A bicyclist rolled along in a wide-brimmed hat, bound under the chin with a scarf. The sun came through forcefully enough to prickle the arms. There was nothing but a smooth-sawn oval on the tree trunk where the wreckage of the flowering branch had been. Inside the office, the artificial chill was so grim it was necessary to open a conference-room window to let in the warmth. The afternoon had enough clouds to blunt the heat; for a moment, at commuting time, it seemed necessary to check the overhead dimness for another threat of rain — but there, instead, were blue gaps opening. Uptown the wind was elating, the sky blown clear. An immense purple-gold cloud sailed across the west, with sharp silver contrails emerging behind it like subsidiary fireworks, and then departed. Shut off the air conditioner and open a window, and in a while, shut the window too.

Notes on the Surrender at Menlo Park

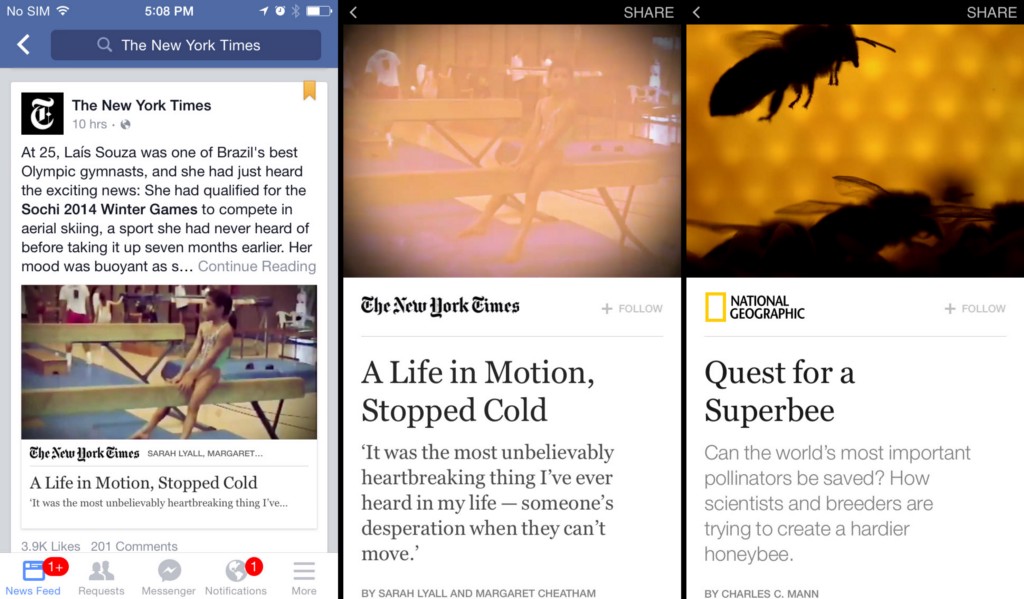

1. The manner in which Instant Articles are seen within Facebook’s News Feed is nearly as important as they way they’re hosted. Yes, they load faster. But the way they are previewed in the feed — differentiated fonts, auto-playing video — gives them a second advantage over everything around them.

2. The first batch of articles is very very very very long. This is as much a reflection of each institution’s anxieties as of its talents. Print publishers are jumping straight in with the long-formiest longform they have, as if to say, “look, Facebook will not interfere with our goal of publishing many very long and Very Good things.” (A little like Snapchat Discover’s first day!) The Times is leading with a terribly sad article about an athlete’s career cut short packaged behind a light curiosity-gap headline and teaser. The Atlantic is using its cover story, a ~9000-word article about a botched execution. NatGeo has a feature about breeding bees to survive the beepocalypse; NBC News, which is using the medium most thoroughly of the newsy group, has a story about almonds in California (they are bad). BuzzFeed has created what appears to be an attempt at the definitive viral post: a “13 Steps To Instantly Improve Your Day” that is really many posts in one, using every available Facebook publishing option (galleries, videos, long photos) to create something that feels like a choose-your-own adventure game in which every ending is Share This Article. The BBC and the Guardian haven’t posted anything yet.* Nothing from Spiegel or Bild, either.

3. Everything is overworked (for now). This always happens when publishers try new formats: It happened on Snapchat Discover, too, where publishers are gradually learning not to OVER-package their videos, because social media abhors conspicuous professionalism. (Conspicuous earnestness is fine, as long as it mimics the network’s local dialect.) This will be fixed when publications just start publishing everything.

4. The article previews display view AND share counts, regardless of what they are. (Update: View counts, which were displayed [seemingly erroneously] under the first posts, are no longer present. Read irrelevant thoughts about this at the bottom of the post!**)

5. In the beginning, having access to Instant will provide a huge advantage over publications that don’t. Eventually, publishers’ numbers will even out as competition increases. Easy traffic will be harder to come by, and certain tricks — as on the web — will wear out and become useless. This will be good in that it will prevent lazy behavior; this will be less good in that it will have transferred economic competition into an environment managed by one other company, which is itself engaged in a separate economic competition. What is a trick, or what is lazy, or what is clickbait or sharebait, is no longer an argument. It is a unilateral assessment (supported by data, of course — data produced and collected by the same company).

6. These articles exist within a separate parent interface in the app. If you tap the Times story, for example, it loads quickly underneath a slim black header bar. Scroll to the bottom and click a “related” story and it will open the Times website in the same frame, but will use that black bar as a loading bar, which moves in a non-linear way (slow at first, then faster). Not a very subtle suggestion! Also, maybe a temporary state of affairs: perhaps those related stories are only links because there isn’t enough native stuff to fill the boxes yet. Why, if you’re Facebook, leave open this pathway to the outside web?

7. That the first batch of stories is, like, MAXIMALIST PUBLISHING, leaves a few questions about advertising. Most of these stories have very few ads, which is flattering to the whole Facebook experience. The Times is showing me a small unit for Shell that looked a lot like a web article ad (blurry, bad, easy to ignore). BuzzFeed’s has an ad at the bottom, but it’s a display unit for one of its sponsored posts on its website. That is: It’s a display advertising unit (a banner ad, basically) for a piece of sponcon somewhere else. Presumably there is a lot we haven’t seen yet? (Facebook is letting publishers keep 100% of revenue for ads they sell, and 70% of what Facebook sells.)

Also: Facebook has spent a long time now trying to find ways to excise “low quality” content from its feeds, by which it meant, mostly, links to sites that hosted image memes but added nothing to them except a whole bunch of ads. What will Facebook think about a one-sentence Instant article with a blurry Minion meme embedded in it? Why give a publisher a share of that? What have they done to earn it, exactly? This, I imagine, could become a point of contention: Facebook’s attempts to define quality are more urgent when they’re the host. One advantage of a centralized internet is that you can easily banish people or behaviors; it is almost necessary, if you acknowledge that your particular platform is imperfect. So Facebook will be in the position of picking winners whether it wants to or not.

8. These stories, for now, only exist in the Facebook iOS app. If you share them on Twitter from within the app — which is an option — you will be sharing a link to web versions of these stories. As I understand it, publishers have basically been given an API for Instant, which they can use to more-or-less automatically export their stories to Facebook. Follow this through:

– Publishers want to publish directly to Facebook because it gives them greater access to Facebook’s users

— This belief in greater access is predicated on the idea that native Facebook stories will share better than linked ones

— If this is the case, and if all stories are co-published on Facebook, the result is that the near-entirety of a publisher’s Facebook mobile is hosted and monetized through Facebook (for some partners this is clearly the intention; for others, maybe not)

Facebook owns an enormous share of mobile traffic overall, meaning that any publication’s mobile web referrals were already composed largely of people coming from Facebook. With wider adoption, Instant would effectively remove Facebook from the mobile referrer pool, and mobile web traffic would plummet — for adopters, totally; for everyone else, more than they might expect. If enough partners use Instant, and if there is enough good Instant content to read, users will begin to regard linked-out stories as weird slow garbage that should Not Be Clicked.

9. Basically: Instant allows publishers to hand over nearly all of their mobile business to Facebook.

10. The Facebook app converts any link to a story with an Instant version to an Instant embed. I posted a link to the Times launch story — the web version — on Facebook. Viewed on mobile, this link was replaced with the Instant story. Makes sense! Remove the inferior version when possible. Death to links!

11. It’s a little weird to see publication employees in this Facebook ad for Instant? Like, some people, sure. But hearing Chris Cox intercut with James Bennet, EIC of the Atlantic, who says, “that’s what’s shareable, good stories are shareable,” before a software montage and a Facebook logo, is………………………………… HMMMM???????

12. Facebook has spent the last few months negotiating with publishers and has made a number of concessions: in response to worries it might cut off audience analytics, it is allowing for third-party analytics, including Quantcast, to tag Instant posts; in response to worries that it would take too large of a cut out of advertising, it is providing friendly rates (though the 100% figure is only accessible to publications large enough to sell ads directly, which is a fairly high threshold); in response to worries that such an arrangement might disintegrate a publication’s identity, they are allowing for custom article styling and fonts; in response to worries that Facebook would capture too much of publications’ businesses, it is allowing sponsored posts. You might characterize this as cautious behavior! Or as friendly. But consider the power differentials between “partners” here. Concessions that mean a great deal to publishers mean virtually nothing to Facebook. Facebook could afford to pay publishers 100% of all ad revenue into perpetuity if it wanted to. Facebook could probably buy every single one of its Instant publishing partners outright! Tomorrow!*** These are less concessions than symbolic assurances that Facebook is not a malicious actor. Almost any arrangements, formal or informal, between Facebook and publishers could be declared invalid or irrelevant whenever Facebook chooses, especially if Facebook’s macro internet situation changes.

To Facebook’s credit — in Facebook’s defense??? — the existence of this power differential makes even good-faith efforts difficult to take as such. But also irresponsible! Every single person in leadership at Facebook could be absolutely committed to the future of journalism and there would still be reasons for caution: all platforms have ideologies, even when they try not to; the internet changes very quickly, so anchoring yourself in one place is inherently risky; Facebook became the most important company in media in a few short years and the next Facebook will probably do the same; above all, Facebook is an advertising company that answers to its shareholders.

And to the various Facebook employees who have expressed surprise and disappointment, in public and to me directly, at the constant criticism their company receives: It’s not about you. It’s not about your ideals. It’s about a reasonable concern, based on the history of the internet and the modern economy in general, that the priorities of powerful partners usually change, eventually, in the partners’ favor. That this seems complex and mystifying from both sides of this arrangement is an example of the incredible power of professional rationalization.

13. Some future controversies we can look forward to: differences spotted in web versions and Facebook versions of articles; publications exceeding vaguely defined standards for, say, violent content; image rights issues (the DMCA never imagined this scenario in its wildest nightmares). Haha, sex stuff. Have you SEEN Facebook’s “community standards?” Facebook is very prudish, historically! Many, many discussions about the ideological opacity of T H E A L G O R I T H M. Idk, some other stuff. It will be crazy-making for all kinds of people. Lots of tweets. Can’t wait!

14. Now that we can see Instant in action,**** we can more clearly see what constitutes a publication on a Facebook-centric internet. A Facebook publication is… a brand? A “vertical?” It doesn’t own its distribution, it doesn’t meaningfully control its sources of revenue. It has no “design” outside of its individual articles. It is composed entirely of its content, as represented to Facebook users by Facebook. A lot of institutional advantages sort of evaporate. What is the difference, from the outside, between a large publication and a small one? One with a hundred reporters and one with ten? One with bureaus all around the world and one with a single office? One with strong institutional politics and one without? These distinctions are to be expressed through Facebook, which means through the News Feed, which means… not very coherently at all. An internet intermediated by Facebook is one in which publications are constantly struggling to stay on the right side of a thin line: are they justifying their own existence on Facebook’s new terms, or are they just weird middlemen introducing inefficiency into a system in which they are very obviously guests? This is slightly worse than a channel relationship. Partners are not guaranteed any more space, or traffic, than they can earn within Facebook’s own structure. They are essentially Facebook users with special publishing tools, legacies, momentum, and an immediate need to make money. Or are publications…. celebrities? No. I mean yes, sorry! Definitely! Congratulations!

15. The selection of the first round of publications will suggest different things to different people. It is a small and prestigious group of large publications; you could average them out, if you wanted, to a center-left ideology. Their selection was probably mostly about demonstrating the platform to the fullest and signaling a certain level of quality. But it immediately poses the question: Who next? There were no outright partisan publications. There were also no token niche or independent publications. They mostly just started at the top. Again: fine! But joining the media means that people will care about decisions like this. These people will be both extremely annoying and extremely not wrong.

234875627839452. Or maybe this is all just a short detour for Facebook. The history of software and web platforms is instructive here: Platforms grow by incorporating the labor of users and partners; they tend, over time, to regard the presence of the partners as an inefficiency. Twitter asks developers to make a bunch of apps using its data, so people make a bunch of mobile apps, then Twitter notices that these apps are actually very important to Twitter, and so Twitter buys one of the apps and takes steps to expel all the other apps, rendering the job of “Twitter app developer” more or less obsolete. In this formulation, publishers are app developers: They are working not only for their own benefit but, in addition, to find ways to increase Facebook’s share of user attention and satisfaction. If they find ways to succeed, through the practice of journalism or some other sort of content production, Facebook will take note. Perhaps Facebook will then devise a way to compensate reporters, or content creators, directly, rather than through the publications they work for. Maybe they’ll just buy a publication! Or many publications. If Instant is a success then, like everything at a functioning technology company that wants to make money, it will be iterated.

45862170348957103946872039568270. This is unspooling into a more general complaint, but whatever. There is toxic mindset that permeates discussions not just about Facebook but about most accelerating, inevitable-seeming tech companies. It conflates criticism with denial and nostalgia. Why do people complain about Uber so much? Is it loyalty to yellow cabs and their corrupt nonsense industry? Or is it a recognition that, as soon as a company reaches its level of importance and future inevitability, it should be treated as important. A word of caution about Facebook is not a wish to return to some non-existent ideal time. Print media was broken, TV was broken, commercial and public radio were broken, local media was broken, web media was very broken. Understanding this — or even just assuming it to be true! — is understanding that it is imperative to seek out the manner in which your media is broken, and the pressures that keep it that way. Worrying about the details of the coming future is merely taking that future seriously. People who insist otherwise? They have their reasons.

23489572089345720938457029384570293845720938452asdkjf. One of the great triumphs of Silicon Valley is its success in framing its companies’ objectives as missions, and their successes as pure contributions to progress. This is a sentiment that would not stand quite so easily in most other contexts: the success of a single business does not map perfectly onto the greater success of the economy, which does not map perfectly onto any useful concept of human progress. Anyway, what were we talking about? This is all going to seem so insane in twenty years. Or two years.

19. Oh, right: So what happens when Facebook goes away? Are today’s publishers, by then, just portable content generators ready to be passed to the next platform? Or have they been replaced by something else entirely? There is apparently only one way to find out!

*This article originally misstated follower counts for the Guardian’s US and UK pages. Sorry and removed! I hope Facebook sends me to future content jail.

**Regarding view counts, which have disappeared, so who cares: “This is a small but interesting choice: It suggests that Facebook sees them as valuable indicators not just to publishers but to users. View counts are one of those things used differently by publishers and platforms: YouTube has them everywhere, even when they’re low; Facebook videos have them too. It was considered sort of scandalous for Gawker to display them next to articles in 2007. One of the things Gawker discovered was that people seem to like to click on things with higher view counts. Now, incidentally, BuzzFeed displays them to readers only sometimes, when an article is especially successful, which is less about trumpeting success than inducing another read. These numbers are a useful display of Facebook’s underlying math — sort of like its News Feed algorithm in miniature. A reader can see that a story has lots of views but not that many shares, or lots of shares but not many more views, or few shares and few views, or more comments than might be expected for its popularity. Readers will assign meanings to these things! And this is now part of the package, even for institutions — like the Times — that had never previously displayed views at all.”

***The ones that could be sold, at least.

****24 hours in, NatGeo (mutant bees) is handily winning the Instant share race.

The CONTENT WARS is an occasional column intended to keep a majority of CONTENT coverage in one easily avoidable place.

The Little Things

A few weeks ago, I ran out to do some errands. Because I was accompanied by my fifteen- month-old daughter, Zelda, we moved at a languid pace. On my own, I would have rushed out the door with my purse and sunglasses and car keys, pulling my seatbelt on as I backed up out of the driveway. I would park at the pharmacy, dart in to pick up a prescription and some nail polish, “no thanks, I don’t need a bag!” and back to the car — or maybe I’d just walk over the five minutes to the nearest grocery store, snag a basket, and race around to grab items from my list, doubling back to the produce because I’d forgotten the lemons.

Trips like this take crazy amounts of time with a baby. But the whole process, once you’ve resigned yourself to spending two hours on errands and gotten the logistics down to a science, can be much more enjoyable. Though you have to pack a totebag of milk and snacks and diapers and a backup outfit just to go to CVS, and though you have to load the baby in and out of the car seat repeatedly, and then in and out of the stroller or shopping cart repeatedly, a small child in a grocery store is a joy. Last Saturday, I realized Zelda hadn’t had a peach since the days of purees, so I picked one out of the bin and handed it to her in the cart. She smiled at its weight, inhaled deeply to smell it, and then tried to bite into it. Babies revel in sensory experiences and a large or decent-sized grocery store is a perfect one: lots of people and action, but space to move around, and a special place for them to sit that is HIGH UP. (This gets very important as they get older and realize the world hasn’t been made to their specifications.)

That said, I don’t always have two hours to kill on errands. A few weeks ago, I had to make quick stop at the grocery store for milk, run by the pharmacy, and hit the bank for cash to pay a handyman at my house. Instead of grabbing the cash at the grocery store’s ATM, I went to my own bank in order to avoid paying a two-dollar fee, because I just cannot. I knew this meant hauling Zelda back out of the car and into the bank, but I did it anyway. As we pulled around to the back of the bank, I noticed something I hadn’t thought about in at least a decade: there was a drive-up window, complete with a special lane painted in the parking lot. The window had obviously been permanently closed some years ago: It was fogged up or filmed over, and it had the general aura of “Hey, I’m a relic of the past!” surrounding it.

I know that drive-up bank windows still exist, but they’re dying off: There’s less demand for them, and they’re undoubtedly expensive to staff when traffic is in decline. I remember going through so many bank drive-throughs with my parents and grandparents; some even had those amazing pneumatic tube systems that shot your check up into the bank, like magic. I hauled Zelda out of the car and into the bank, set her down in front of an ATM and, as I waited for my cash, watched her amble around the bank, bumping into strangers and smiling up at them.

Last Friday, I took Zelda to her pediatrician for a checkup. Though I live more than thirty miles from Greenpoint now, I decided to take her there because I have become emotionally attached to the practice. But for reasons I will never fully explore, rather than drive to the train station ten minutes from my home and ride the Metro North into the city, I decided to drive her all the way there alone. We arrived, sweaty and hungry, two hours later. We strolled in our old neighborhood, Zelda got her two shots, then we were on our way. As we drove out of Greenpoint, I realized that we needed to get gas. It wasn’t a desperate, on “E” situation, but I didn’t feel like tempting an out-of-gas experience in the heat and traffic with a baby. We pulled into the station, I got out of the car, and slid my card through the reader, staring at Zelda in her car seat, who was still smiling because she didn’t know we had another two hours of transportation Hell yet to go. The machine didn’t take my card. I swiped another. It “processed” for a while, then gave me an “Error” message. I looked around and realized the other patrons of the station were experiencing similar failures, and were heading inside to pay the attendant directly. I backed up to another pump, and tried a second credit card machine. It also failed. “Come inside to pay!” an employee from within barked at me over the PA system. I looked in at Zelda; she had passed out. “Oh no,” I laughed to myself, “I’m not hauling her in there when it’s possible she will sleep all the way home.”

I can’t argue that we don’t live in a “convenient” era. Bank of America shut down a bunch of drive thrus because it could, since we have entered the era of “self-service,” their PR person told me, and many people use apps to bank instead of going into the building. I can order a car, or have my groceries delivered to me, find a doctor who will come over to my house, all from my phone. But the new way, the startup, app way, is just me interacting with an app: sometimes, these days, what I need is another human’s assistance. When you become a mother, you are often nodding gratefully and thankfully at people for helping you with your stroller onto the subway, or giving you a seat on the bus. You feel overwhelmed with love when people hold open a door for you, a woman with a baby in a stroller and a bag and a purse on her arm. Sometimes, too, I think, I’d be willing to pay a bit more for my everyday errands for a little helping hand.

What would I have paid, in that moment, for a full-service gas station? An extra fifty cents a gallon? Maybe an extra dollar! In pockets of the world, these small conveniences surely still exist. But it’s not my oldness that makes me want to have these things back, and it’s not nostalgia; I don’t think Zelda will be any worse off for never having seen the pneumatic tubes carry a check to the bank teller two feet away from our car. And it’s not quite laziness, either; I am a type of lazy, but not the type that doesn’t want to get out of her car pod at all costs. But in the year and change since having my baby, I’ve realized that these dumb conveniences, which never seemed to matter to me ten years ago, they served a purpose: They were for tired moms just trying to get fifty bucks or a tank of gas without hauling a mad and tired baby in and out of the car every thirty seconds.

I got in the car and, as we pulled away, gasless, my iPhone randomly Bluetoothed into my car’s stereo system and began blasting “Ms. Wrong” by that dog. “What is this, 1995?” I asked, to the air. “Hi! Hi! Hi!” Zelda said from the backseat. For a second, I sort of wished it were.

Photo by Daniel Oines