Are You Subsidizing Your Employer?

“Decades worth of collective bargaining may have led to the delivery of acceptable health and safety standards in the workplace, but what good is all that legislation if the rise of hipsters working in coffee shops or on park benches has created an entirely new norm for acceptable worker environments just because the boundaries of the office space no longer have to be respected — one where it doesn’t matter where you are or what you’re doing, as long as you’re connected, you’re deemed available for work-related matters. Which prompts the awkward question: how long until we find ourselves providing not just our personal capital, data, energy and time on voluntary grounds to our corporate overlords but paying them a tribute for their protection as well? You might say, well, that’s a slightly far-fetched concept at this stage. We’d say, actually — it’s not too removed from the extreme profit maximisation strategies being applied to new business models in Silicon Valley tech lord world today.”

The Hottest Pitcher in America Teaches You How to Pitch a Fastball

by The Awl

What if we could all marry Daniel Norris and live in his van with him and go surfing and also pitch superlative two-seam fastballs? What then?

New York City, March 11, 2015

★★★ Water beaded in the bottom of the sheet-metal box of Star Wars figures where it sat on the air conditioner vent. Something like rain lurked for a while and then went away, leaving sharp light and dull air. It was time to close the blinds when going out for the day. Downtown, the breeze came up Lafayette almost gusting, as if cheerfully pleading helplessness. Gray moved in from the harbor, with the scent of the harbor pushing ahead of it, the wind now swirling cool and warm. There may have been the sound of thunder; it may have rained somewhere. The streets around stayed dry, but the heavy warmth lifted. A clean drop-top Chrysler blasted old music out into the street. The haze on the river uptown looked like a sentimental illustration or a trash fire.

Ask the Publisher: What the Hell With This Verizon/Aol Thing?

Verizon and Aol Why? What? Hmmm? These are just three of the many questions the world had about today’s $4.4 billion acquisition.

They were met with hundreds of responses. Given the subject matter — content blobs and ad tech — these responses were fuzzy and conflicting. Did Verizon just buy a bunch of blogs? The future of web advertising? A scam timeshare in content shitworld?

I asked Michael Macher, Awl Network publisher and advertising expert (I hope????), to explain.

John Herrman, Awl Content Producer: Publisher, why did this happen?

Michael Macher, Awl Content Monetizer: The answer is pretty simple on the Aol side of things: Verizon has deep pockets and will help Aol scale its adtech and media business at a much faster rate. For Verizon, who already spends a substantial amount on advertising with Aol, it’s about streamlining their marketing and accessing Aol’s sophisticated programmatic advertising channels.

From the content side (the blogs, HuffPo, etc) this is sort of strange: there are a lot of companies I might have expected to sell before Aol. So I’m inclined to believe this is mostly about advertising? But I thought web advertising was terrifying and changing all the time. Why would you spend four billion dollars on it?

Yeah. I think the content side of things is more of a byproduct of this deal, rather than the focus. There is already talk of Aol’s brand group (which includes the premium properties like HuffPost and Techcrunch) spinning off. Four billion dollars is a high number, but for a consolidated tech platform for mobile and video, it’s not as ludicrous at it initially sounds. It’s a drop in the bucket for Verizon, especially if they do spin off the premium content side of the business.

I’ve heard you talk about programmatic ads a lot. They’re… like automatically allocated/bid-upon ads?

Programmatic is basically an umbrella term that means automation, and there are different ways brands leverage tech to make the ad buying process more efficient. RTB, data and audience buying are all subsets of what we call programmatic. (Actually Aol pretty recently fired most of their “direct” sales staff to make more room for programmatic specialists.)

“Direct” being like Aol ad humans who would set up deals directly with advertisers or their ad agencies?

That’s right. These are your classic ad sales people who schmooze with clients over drinks. After that ad sales person convinces a brand or media buyer at an agency to sign a contract for, say, $1,000,000, human ad operations people would then manually set up that campaign in their ad server. Then there’s reporting, campaign optimizations, invoicing etc. The whole thing takes a lot of time and energy.

So the programmatic deal is like, you plug your site/content operation into some sort of machine, and instead of shaking hands and talking up your audience, you… pray? Use data? Leverage demographic insights to ensure maximum brand reach?

Programmatic deals all happen over a tech platform that allows the media buyer to decide where their media runs, at what CPM [rate, basically], and for which audience all without the manual processes required in a direct deal.

So the media buyer (person placing the ad) has a sort of big buffet, or like, an interface where they can check various options.

Here’s a simplified version of how it works: Publishers plug into systems called SSPs (supply side platforms) where they, like, package their inventory (by vertical or demo etc). Then buyers access this inventory over DSPs (demand side platforms). You might say “package their inventory into buyable chunks” or “segments.”

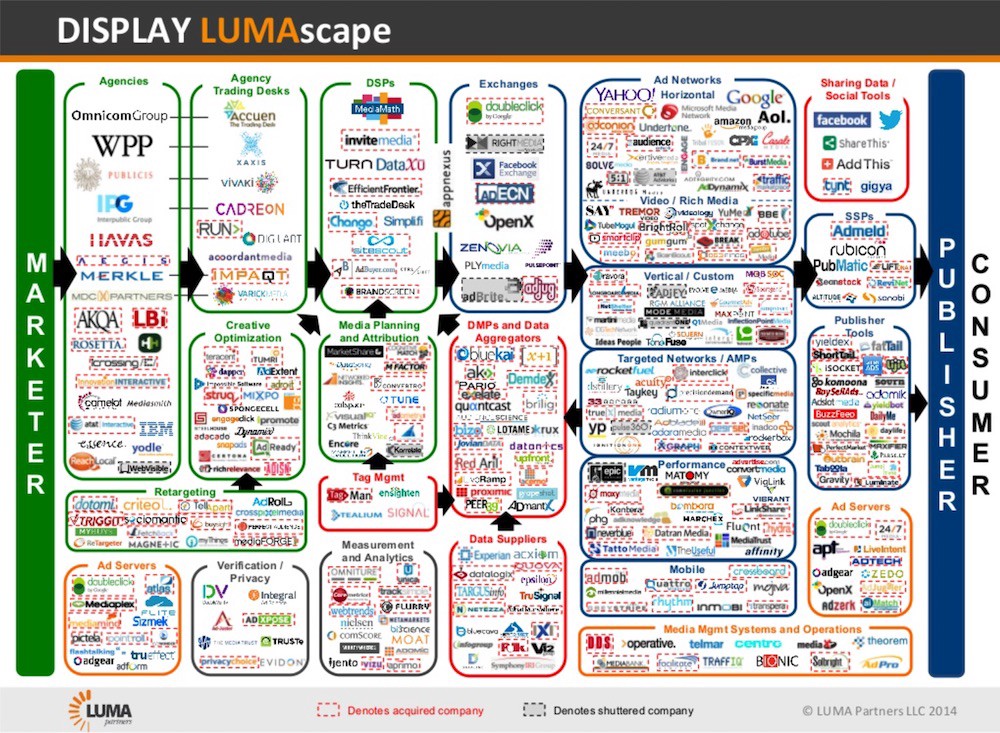

Right, and this is a pretty huge simplification of the dreaded LUMASCAPE world, right? Or is this one more addition?

Haha YES. For those who haven’t seen the LUMASCAPE, it’s an insanely complex graphic that shows all of the technology and intermediaries that stand between advertisers and audiences. These are data providers, ad servers, creative agencies, ad exchanges etc. ANYWAY, Aol is an ad exchange — or a marketplace where buyers and sellers can meet.

This interview is mostly an excuse to embed that photo.

As a publisher, I completely understand. I think the LUMASCAPE should be embedded in every piece of content, regardless of whether it’s relevant.

So Aol’s programmatic exchange is growing, and that’s interesting to a Verizon because programmatic overall is growing. Is there a sense that their style of ad-selling is THE FUTURE of at least some parts of the internet?

Internet ad spend was something like $121 billion in 2014. That’s going to increase as more advertising moves to digital. And programmatic is increasingly the framework in which digital advertising transactions occur.

So who does this matter for? This isn’t Facebook or Google. This is like… sites and site-like things. Or: What is the market for this? Who is now facing down programmatic as this inevitable thing?

It’s not super interesting outside of the adtech sphere. It matters for publishers and advertisers using Aol’s platforms. It’s a confirmation that programmatic matters on a large scale and while this particular merger might surprise some people, the underlying logic isn’t surprising.

So in the future, Verizon hopes, people are selling ads all over the internet through its network, like a big automated centralized clearing house. Or delivering ads in Verizon-world, whatever that means.

Not to mention Verizon now owns a huge marketing distribution wing for their own campaigns. Which they’ll be able to push out for cheaper and at a larger scale. It’s all incredibly boring actually!

Rude. So us, the Awl Network. This is relevant here. We might be selling inventory through VerizAoln.

Yep. Aol Marketplace is actually one of our advertising demand sources. So kind of. Though the effects likely won’t be super significant to us.

Are they the biggest game in town, programmatic-wise?

Aol is big in adtech. But it’s a highly competitive space with a host of major players. There’s Google’s AdX obviously, which is a behemoth. Not to mention AppNexus, OpenX, and more. Microsoft has a pretty sizable ad network, and Yahoo acquired its ad exchange overnight when they purchased Right Media in 2007.

None of those companies are quite a Verizon, though. I guess that’s what seems weird? You hear about consumer web companies buying adtech firms pretty often and you’re like “sure, one more revenue contraption in the web apparatus, whatever.” But Verizon?

Aol differentiated itself by being good at video. They bought 5min Media — then later Adap.tv. When they plugged those into HuffPost’s inventory they became a major force.

From the outside I don’t really get what that means, that they were “exceptionally good at video.” Video from where, seen by whom?

It means they had a TON of people watching video, and a ton of advertiser demand looking to access that audience. And a strong tech platform for connecting the two.

BUT WHAT VIDEO? WHERE?? Like within Aol properties? Or also through advertising arrangements outside?

Any type of video “content” running on websites plugged into the system. With 5min they bought a library of thousands of videos, which could then be distributed across HuffPost in “contextually relevant” articles. These videos could be cooking tips, or short interviews, or DIY tutorials, or more cooking tips.

Oooohhh, so the vast wilds below/near articles.

HuffPost was a major syndication platform, but there were tons of other sites in the network as well. Back in the day, advertisers would often buy tons of pre-roll impressions against video content in specific verticals, without ever knowing where that content ran. For example, 99% of a huge campaign budget might run on just one or two less-than-premium sites — whereas only 1% might show up on a brand name web property, etc. There was not a lot of transparency then, and a lot of video buying still works that way.

It seeeeems like programmatic would, among many many other things, alter those arrangements. Like, you take out a few layers, you remove a few opportunities for, let’s say, euphemistic descriptions of content/readers/placement.

Exactly. In terms of transparency, things may not be so different. However, now that advertisers are buying audiences — they at least “know” that they are targeting their core demo. The point of audience buying is that it’s site agnostic, but the more sites you have plugged in the better. And it still might be the case that a disproportionate amount of video views could come from a handful of sites.

Or from creative ad units on existing sites. One thing: This still feels pretty firmly outside of social platforms. It sounds like a big change for display advertising and video on the web but doesn’t seem like it cracks open the door to any of the huge platforms that publishers (and advertisers) are staring down right now.

That’s right. The type of ads being bought and sold programmatically have largely emerged in parallel to social platforms, not within them. Programmatic channels and social will still compete over ad budgets — especially for video.

So a social media triumphalist might say like… who gives a shit? This is a dead web. Alternatively someone less bullish about the biggest platforms and apps might say, well, this is a separate, less centralized, less contingent thing. (That many companies are attempting to turn into a platform, lol.)

Haha, they might say that! At the end of the day, what really matters is demand. And there is still significant demand for ad products that exist outside of the social realm. And you can still buy Facebook and Twitter through some DSPs. There is always the capacity to integrate those worlds, and some are already making headway.

So either a whole bunch of people use Aol’s programmatic stuff to buy and sell ads, and/or it becomes some sort of revenue thing inside a big mysterious video…. thing, or it evaporates into thin air taking piece of the internet with it.

I think any of those are possibilities.

Ok good.

With Verizon’s money behind the platforms, we can expect AOL’s adtech platforms to wrap its tentacles around more publishers while shoving more advertising demand through…those tentacles.

Nice, nice.

You can edit all of this for clarity.

Nope I think this is very clear, thank you.

Podcasting and the Selling of Public Radio

by Conor Gillies

A couple of weeks ago, NPR and two of its most influential member stations, WNYC and WBEZ, invited a large group of media and marketing people to Le Poisson Rouge, a nightclub in Greenwich Village, for an event called “Hearing is Believing.” Its purpose was to persuade brands to advertise on public media podcasts. Onstage, some of the most listened-to podcasters — Jad Abumrad, Guy Raz, Glynn Washington, Brooke Gladstone, Lulu Miller — presented public radio’s offerings: an intimately engaged audience, a unique narrative platform, a chance for “Mail Kimp”-level virality. Later, after an indie band performed, Ira Glass, the host of This American Life and producer of Serial, told a reporter for AdAge, “My hope is that we can move away from a model of asking listeners for money and join the free market.” He added, “Public radio is ready for capitalism.”

In 1961, during a broadcast-industry convention, the message public media delivered to the private sector was quite different: In what has become known as the “wasteland speech,” Newton Minow, then-chairman of the FCC, criticized the corrosive effects of commercial media and mapped out a vision for ad-free, publicly supported alternatives. “The people own the air,” Minow reminded the crowd. The efforts of Minow and his fellow social democrats coalesced into the 1967 Public Broadcasting Act, which led to the founding of PBS and NPR, and established the rule that so-called noncommercial educational broadcasters must make clear where their money comes from — but without advertising in order to limit private influence on public airwaves.

Since then, the FCC has required that public broadcasters acknowledge their sponsors through underwriting spots — short, neutral, non-promotional messages made for “identification purposes only.” But on the internet, those rules are basically null; there is no publicly owned digital commons to regulate, and the FCC has no say yet over public broadcasters’ websites, apps, or podcasts.

“Podcasts are not donated airwaves. They’re podcasts,” Erik Diehn, the vice president of business development at Midroll Media, a podcast media company, told me over the phone. “There’s no exchange happening where the broadcaster has to agree not to take ads because they are being given this grant of a public good.” Midroll Media produces original shows like WTF with Marc Maron and Comedy Bang! Bang! and sells advertising on nearly two hundred podcasts, including shows from Public Radio International (an NPR rival), like Studio 360 and Science Friday. The company’s ads — “integrated, native, often host-read spots” — are hugely effective compared to most internet advertising, so businesses pay good money for them. Podcasts, which tend to run one or two ads before the show and two or three ads during the show, can earn around three hundred dollars per ad if they average at least ten thousand listeners. For the elite circle of shows with over four hundred thousand listeners — generally the iTunes Top 50 — a single ad spot can net over ten thousand dollars.

While there are a few legal hurdles facing public media’s entry into the free market, for the first time, U.S. public radio will be able to broadcast commercials.1 And because hosts and producers aren’t just offering ad space, but effectively branding content, they are threatening a long-protected public trust.

NPR has allowed corporate sponsorship of their podcasts since at least 2003. Back then, funding credits followed on-air rules for underwriting: a short, neutral message, usually at the start of a show. Sponsor, slogan, website. This year, NPR began rolling out longer, more promotional spots, as in calls to action for a business, in the middle of their shows. On Car Talk, Ray Magliozzi makes first-person approvals of products punctuated with his signature laugh. In a recent episode of Fresh Air with guest Louis C.K., an ad for stamps.com — though not voiced by Terry Gross — is scored with music from the soundtrack to Louie. NPR’s new flagship podcast, Invisibilia, runs two thirty-second spots together in the middle of the show, produced with funky music and lively voices that interchange, Radiolab-style.

“These credits cannot be voiced by NPR journalists, but non-journalist hosts of entertainment podcasts may voice credits,” Bryan Moffett, interim president and CEO of National Public Media, which handles NPR’s corporate sponsorships, told me in an email. “We will not offer endorsements, testimonials, specific product prices, or promotional calls to purchase. Podcast credits may mention an offer or discount for podcast listeners, and tell them where or how to get it, however.” NPR’s podcast sponsorship guidelines have yet to be further defined, Moffett said. But NPR is committed to maintaining “a non-commercial posture with sponsorship on digital platforms because users expect us to have the same sound and non-commercial feel everywhere they listen or experience NPR.”

When I asked Kerri Hoffman, chief operations officer (also my former boss) at the Public Radio Exchange, a Cambridge-based nonprofit that produces and distributes shows like Reveal — whose host Al Letson has started reading ad copy mid-show — about their podcast sponsorship policy, she said, “We actually encourage our hosts to deliver spots in keeping with the sound of the show. We do ask that they identify sponsors as such — to make it clear that it is a paid sponsorship.” As for underwriters sending producers gifts, as podcast advertisers sometimes do, so that personalities can personally endorse products, she told me, “I think this is absolutely of concern with news shows. It is a little less clear with entertainment programs.” She told me producers do a great job policing themselves. Most shows on Radiotopia — PRX’s podcast network funded, in part, by large grants and listener support — make sure that sponsor products aren’t too closely aligned with show topics, for example.2

Maximum Fun takes a more old-school approach to underwriting. “Generally speaking, we try not to have more than two ad spots in a show, we keep them short and avoid personal endorsements, hard selling, and products we don’t like,” Jesse Thorn, host of Bullseye and the network’s president, wrote in an email. “We’re listener-supported, and we love to have companies support us as well, but advertising isn’t the core of what we do.”

In this early stage of podcasting, listener expectations are far from set. The “sonic environment” of podcasts, as Diehn put it, isn’t like that of the radio dial, which makes the difference between commercial and noncommercial channels clearer. When listeners subscribe to podcasts — six is the average number — they don’t necessarily hear institutions or networks; they hear individual producers from a variety of backgrounds making similar choices. “So when you hear an ad on This American Life that sounds not too different from WTF, it’s all consistent in the listener’s soundscape.” He added, “Those ads tend to not be obtrusive. They tend to sound good. They tend to sound like the rest of the show. So I think as long as you stay in that range of listener expectations, you’re not going to offend listener tastes too much.”

Benjamen Walker, host of the Radiotopia podcast Theory of Everything, isn’t so sure about the true cost of these ads. “No one’s getting paid enough for what that means: using your own credibility, your own voice — the reason people are listening to your show — to read the ad copy,” he told me over the phone. Walker has started reading ads at the end of his show, the way Roman Mars does in his podcast, 99% Invisible. “The show’s over. That bothers me a lot less,” he said. But when it comes to public radio people reading ad copy at the beginning or middle of a show, Walker told me “that’s a terrible, terrible idea.”

“The leg up that public media folks have going into podcasting comes from this connection to the listener-supported content model,” he said. “And for us to endanger that with the fucking ads seems like a terrible idea. Who’s going to want to give support for their favorite podcast when they hear eight million ads?”

Advertising on public radio doesn’t totally undermine the virtues that make public radio public or worth supporting; we accept ads on city subway platforms and in non-profit magazines.3 However, what makes these ads troubling is that they don’t sound like ads: They sound like public radio. They exploit a special kind of trust listeners reserve for noncommercial educational media — a trust built over decades and deeply connected to the distance producers have maintained from a profit motive — to get listeners to buy things. Advertisements, no matter how relevant or blended-into-the-tone-of-the-show they are, serve only to extract dollars from the listener. Public radio serves a civic good.

When Jay Allison, the great curator and de facto leader of public radio here in the states, gave a speech in 2011, he defined public radio as “a mission-based enterprise.” He said:

Mission can become inconvenient sometimes, too much work. Understandably, as an enterprise, we crave success, too. And money. For one thing, those are quantifiable. And this is tricky, because when success and audience numbers and money are the goal, our mission can become a burden. There are easier ways to get money, and we get lazy. … The original purpose of public broadcasting, I think it’s worth remembering, was broadly educational. Education is an unassailable civic good.

We’re getting lazy.

Think of the old Newton Minow principle: what interests the public ≠ the public interest. Clicking around the internet, it’s clear that we’ve entered another wasteland, only now we face the omnidirectional pressures of data brokers and targeted advertising, of competition for likes, shares, and unique visitors, of the entrepreneurial (journopreneurial?) class’s gospel of monetization. With their “personalized storytelling” and “especially sticky audiences,” podcasts might seem like a “pretty natural fit” for native advertising. But shouldn’t public media, of all things, avoid mixing commerce and culture?

“This line between what is public media and what is not doesn’t exist anymore,” Walker says. “But I think aesthetically you, as a creator, can guard what you do and what you don’t do with your own voice.” Public media organizations would be served well, then, to at least write out their podcast sponsorship guidelines — as they would a privacy policy — to keep ads minimized and commercial pressure away from people making art and news. Do you air ads in the middle of a show or in the credits? Who produces and voices the ads? How long should they be? Can anyone sponsor a show? Do you treat entertainment different from news? Should producers be sent gifts from their underwriters? And really, listeners should have the final word.

Maybe, once the dominant public radio sound — which owes everything to This American Life’s twee first-person storytelling and fake populism — is sold off, a rising generation of listeners and podcasters will want to organize around something different, online. Something more community-minded. Or something that at least takes its audience more seriously. Maybe something closer in spirit to Radio 4, Home of the Brave, PRX Remix, Berlin Community Radio, The Biggest Story in the World, or Paper Radio. A new, more democratic, public media for the internet. What would that sound like?

1. Here are the legal hurdles. First, public broadcasters, like any registered U.S. nonprofits, need to pay tax on revenue from advertisements, defined by the IRS as: messages containing qualitative or comparative language; price information or other indications of savings or value; an endorsement; or an inducement to purchase, sell or use any company, service, facility, or product. Also, according to Jeffrey Tenenbaum, a non-profit tax lawyer, nonprofits can’t raise a substantial amount of money — the number is around twenty percent of total income — from unrelated business, or they risk losing their tax-exempt status. Finally, by inserting ads into their podcasts, public radio stations run the risk of violating contract agreements, like with music publishers who limit use of their recordings to noncommercial purposes.

2. The distinction between crowdfunding and real public funding is worth keeping in mind. As Astra Taylor writes in The People’s Platform, “Crowdfunding allows individual creators to raise money from their contacts, which gives well-known and often well-resourced individuals a significant advantage. In contrast, a government agency must concern itself with the larger public good, paying special attention to underserved geographic regions and communities.”

3. As a case study of one, here are my own habits when it comes to audio-related stuff and giving money. I am a twenty-four-year-old white male whose annual income falls under fifty thousand dollars, and as of May 12th, 2015, I listen to real radio more often than podcasts, but I do subscribe to the following shows through an app called Podspace on my Moto E smartphone, which I usually hook up to a monaural Tivoli speaker around bedtime: Fugitive Waves, The World in Words, Theory of Everything, FACT MIXES, Car Talk, Ideas, 99% Invisible, The Bugle, Short Cuts, Comedy Bang! Bang!, In Our Time, Between the Ears, Love + Radio, Re:Sound, and Radio Diaries. I give five dollars a month to MPBN to support public media in my home state of Maine. I started giving ten dollars a month to WMBR in Cambridge, where I live now, during one of their pledge drives, because I love them and want to help them however I can. I gave forty dollars to Radiotopia’s Kickstarter campaign. I did not give anything to Serial when Sarah Koenig asked for money, not because I was annoyed by the manufactured vox pop commercial but because the show felt like blockbuster entertainment, and I don’t see the point of supporting just one show.

Correction: Maximum Fun does not operate as a non-profit.

Photo by Patrick Breitenbach

Eat the Greek Yogurt (Correctly)

The Greeks have a few different words for what we call “yogurt,” which makes sense, because yogurt is a major part of their diet and over the millenia they’ve been eating it, they’ve recognized that there are several different kinds. Today, a decent-quality supermarket in America now includes American-style yogurt, Greek yogurt, Icelandic yogurt, drinkable yogurt, yogurt with various toppings, and yogurt with disastrous neon colorings and flavorings.

This is fine. Good, even. I like almost all of those yogurts! But because American-style yogurt, which is thin, mild, and usually sugary and/or heavily flavored, was by far the most popular variety of yogurt in this country up until just a few years ago, it still colors the way we think of all yogurt. Which means that Greek yogurt is often mistakenly treated the way we would treat American-style yogurt. This is obviously wrong. Greek yogurt is best thought of not as a yogurt, but as a soft white cheese.

In Greece, there is a strained fermented dairy product called “straggisto” which is fairly similar to what is branded as Greek yogurt here. In fact, most of the Mediterranean and Middle East has some variety of strained yogurt-type product. Straggisto yogurt in Greece is sometimes mixed with honey or fruit preserves in the way that we will sometimes drizzle goat cheese with honey. But more often than not, it appears in a savory dish: tzatziki, a mixture of yogurt with chopped cucumbers, olive oil, and sometimes lemon and/or herbs.

That’s not to eliminate all sweet Greek yogurt dishes; soft cheeses, which include creme fraiche, cream cheese, and ricotta, are great in some desserts. What they are NOT great in is American yogurt dishes. Like parfaits. For the love of god, stop putting Greek yogurt in a bowl and topping it with fruit and granola. Imagine sticking a blob of cream cheese in a bowl and covering it in granola. That’s what Greek yogurt parfaits are. A yogurt parfait works with American-style yogurt because it is airy, sweet, and has not been drained of most of its water and lactose; the yogurt is comparatively mild, won’t overpower the other flavors, and has a high water content so it mixes easily.

Greek yogurt, on the other hand, works well with vegetables, with meats, with herbs and spices. It adds creaminess and fattiness and a bit of tang, which makes it a great helper for vegetable dishes. That’s assuming you buy the right yogurt, which many people do not. Full-fat Fage is the best option that can be found almost anywhere. The zero percent Fage yogurt is also very good, but it can be crumbly, so it won’t work as well for certain dishes. Any of the major American-style yogurt brands’ attempts, like Dannon’s “Oikos” or Chobani, are total bullshit.

Once you’ve got the right yogurt, it’s easy to use. It might feel weird using something from the yogurt aisle in savory dishes, but an easy way to use it is to simply replace various other soft white dairy products with Greek yogurt. Any recipe that calls for creme fraiche, sour cream, or cream cheese can almost certainly be made in exactly the same way with Greek yogurt. Many more cheese-like dairy products will work too — goat cheese, ricotta, queso blanco, and even feta, sometimes. It also works, rarely, in place of mayonnaise.

Asparagus With Herbed Yogurt And Roasted Almonds

Shopping list: Asparagus, Greek yogurt, garlic, olive oil, parsley, thyme, chives, lemons, raw almonds, butter, sugar, cumin, cayenne

Pre-heat the oven to 375 degrees. In a small saucepan, melt two tablespoons of butter. Add in a pinch of sugar, a pinch of cumin, and a smaller pinch of cayenne and stir to combine. Toss in a handful of almonds and stir until they’re all coated. Spread evenly on a baking sheet and roast in the oven for about ten minutes, until fragrant and toasted. Eat one to see if it’s done; it should be crisp, not cardboard-y the way raw almonds are, but not burnt. Try not to eat too many of them.

Take a microplane grater and grate two cloves of garlic into a bowl. Add in one small container of Greek yogurt. Chop a bunch of herbs very very finely; the ones I listed are just a suggestion, pretty much anything works. Add the herbs to the yogurt. Squeeze half a lemon’s worth of juice into the yogurt, and pour in a tablespoon of olive oil. Stir to combine and let sit.

Put a cast iron pan on the stove over medium-high heat. Chop off the woody ends of the asparagus but keep the rest of the stalks whole. When the pan is hot, pour in a tablespoon or so of olive oil and, before the oil starts smoking, throw in the asparagus. Turn frequently; you want a little bit of char, but they should still be firm and crisp. Shouldn’t take longer than three minutes. Salt and pepper to taste.

Lay the asparagus down on a plate. Spoon the yogurt sauce over it and scatter the almonds over the top. Finish with a drizzle of olive oil and/or lemon juice if desired.

Beets And Toasted Israeli Couscous With Harissa Yogurt

Shopping list: Red beets, Israeli couscous, red harissa, Greek yogurt, radishes, arugula (alternately: get beets with the greens attached), fresh mint, olive oil, orange, red wine vinegar

Preheat the oven to 350 degrees. Spread the dried Israeli couscous as evenly on a baking tray as you can; they’ll roll around but don’t worry about it too much. Put it in the oven for about five minutes, watching carefully, until golden. Remove from oven and turn the heat up to 400 degrees.

Trim greens from beets, if they’re attached, and save them for later. Wrap each beet completely in aluminum foil and stick right on the bare rack of the oven. Roast for, I don’t know, forty-five minutes or so, until tender. Let cool, then peel. Wear gloves if you don’t want your hands to be pink for the next twelve hours. Chop beets into cubes.

Cook the couscous the way you normally would, which is to say like any other pasta: bring a pot of salted water to a boil, toss ’em in, cook until al dente, maybe seven minutes. Drain.

Squeeze half a small orange’s worth of juice into a container. Throw in a small container of Greek yogurt, and pour in a tablespoon or two of olive oil and a couple teaspoons of red wine vinegar. Mix thoroughly; it should be about the color of the beets. Also chop some mint, and slice some radishes.

To plate: put the toasted couscous down on the plate, scatter beets on top, stick the radishes in between the beets, pour the yogurt dressing all on top and around, and scatter the mint. Finish with a touch more olive oil.

Roasted Rhubarb With Sweetened Yogurt

Shopping list: Fresh rhubarb, white sugar, Greek yogurt, honey, fresh basil

Here’s how you do dessert with Greek yogurt. Pre-heat the oven to 400 degrees. Trim the ends of the rhubarb and chop the stalks into about four-inch pieces. Place them down on a baking sheet and scatter sugar all over them. The amount depends on the tartness of your rhubarb, but it shouldn’t ever be, like, covering the rhubarb. Maybe two teaspoons per stalk. Put in the oven and roast until very tender, maybe half an hour.

Mix your yogurt with honey in about a 3:1 ratio. Add salt, too. Chop some basil however you want to; a chiffonade is fine if you’re a shithead like me who wants to show off, or you can just tear it into smaller pieces with your bare hands. It’ll taste exactly the same.

To plate: in a bowl, place a few stalks of roasted rhubarb on one side, and tilt the pan to add some of the juices on top. Take a spoonful of the sweetened yogurt and put it on the other side. Add basil on top.

These recipes barely crack the surface of what you can do with Greek yogurt; one of my favorite stupid recipes is to mix it with cilantro and cumin in it and plop it on top of nachos, or add (with pickled onions and mustard) to a hot dog, or, hell, just mix in some olive oil and lemon and dip in any kind of bread product. This isn’t to argue that Greek yogurt isn’t spectacularly versatile; I’d merely suggest that it’s a mistake to treat it as if it was American-style yogurt. When you see “yogurt” you shouldn’t automatically think “breakfast.” You should think “cheese.”

Photo by Klearchos Kapoutsis

Leonard Cohen, "Got A Little Secret"

It’s funny — good funny — to look back now at how we used to think of I’m Your Man and The Future as late-period Leonard. Anyway, here’s a basic blues from his latest live collection, which we will hopefully someday similarly look back at as another middle period. Anyway, enjoy.

Prophet Ascends

Verizon, which operates the largest cellular network in the U.S., has acquired this man, Shingy, for 4.4 billion dollars. Incidentally, it will also own whatever company currently employs him.

Celebrity's Unorthodox Version Of Hashtag Activism Involves Actually Doing Things

“It’s all very well for me to sit in my cosy leftie bubble with my baja-sporting friends, spending our free time attending vegan popup barbecues and meeting in art centres to have a bit of a moan about Ukip; we missed the changing climate of British politics. We dismissed the growing support for the right wing as just a few comedy racists, underestimated the momentum they were gaining, and thought that by retweeting the latest Owen Jones article, we were doing our bit. Wrong. We need to take the action we should’ve taken before, now.”