Baptism by Song

by Casey N. Cep

There are many ways to take a bath, and just as many ways to perform a baptism. Some Christian traditions sprinkle a little water on the foreheads of infants or adults, drop by holy drop, and call it a day. Immersion is something else, and plenty of denominations have full-body fonts in their sanctuaries — or know where there’s a river or creek nearby deep enough for wading. Lots of hymns are available to mark the occasion, but country music also has its fair share of songs about baptism.

Carrie Underwood had a big hit last year with “Something in the Water,” a song she co-wrote about following a “preacher man down to the river,” experiencing a conversion where you get “washed in the water, washed in the blood.” In his 2008 song, “Muddy Water,” Trace Atkins sang, “There’s a man in me I need to drown,” while almost a decade earlier, Kenney Chesney recorded a beautiful duet with Randy Travis called “Baptism” where “it was down with the old man, up with the new: raised to walk in the ways of light and truth.” That imagery is borrowed from the liturgy itself, which usually begins by evoking the protection of Noah and his family from the flood and the parting of the Red Sea so that the Israelites could pass safely; it’s not only a time to consider the baptism of Jesus in the Jordan, but more perilously all the times that people were drowned, right along with their sins.

It is a serious, somber business, and yet if it you’ve done your part and God does God’s part, there is real joy in the idea that the old is made new. Take Randy Travis’s other baptism song, from his gospel album, Rise and Shine: A lighter song, “Pray for the Fish” has a catchy chorus about the piscatorial witnesses to an immersion baptism. “They won’t know what’s coming, when the sin starts rolling off the likes of him. Lord be with ’em, they ain’t done nothin’. Please, won’t you leave them just a little bit of room to swim?”

It’s hard to imagine a religious ritual other than marriage that gets this kind of attention on the radio. But these songs do well because even if you don’t believe in the saving power of the rite, they tell a story of change. These songs are all about men and women who are living a certain kind of life and then decide to live another. That’s why one of my favorites sketches a full life in only a few verses, where the old life is every bit as important and evocative as the new one.

Dallas Frazier and Whitey Shafer wrote “The Baptism of Jesse Taylor” in 1973. “Among the local taverns there’ll be a slack in business” and “among the local women there’ll be a slack in cheatin’,” the song begins. Why? Well, because when “they baptized Jesse Taylor in Cedar Creek last Sunday Jesus gained a soul and Satan lost a good right arm.”

And while a lot of folks have covered this song about a ne’er-do-well who finds religion — everyone from Tanya Tucker to George Jones — it was the Oak Ridge Boys who did it best. By the time they released their version, they’d already won a Grammy, but they won another for it in 1974. The thing about the Oak Ridge Boys cover is that they take you deep down under the water, and then up, up, up toward the heavens. They bounced around between country, gospel, and pop, but it’s a song like “The Baptism of Jesse Taylor” where you really hear their best. They sound like they’ve known more than a few Jesse Taylors, with scarred knuckles that “were more than just respected.” They wallow in the verses about Jesse’s misdeeds, and revel in the ones about his new life. There’s real joy in their mention of his wife Nancy and son Jim: “Now Jimmy’s got a daddy and Jesse’s got a family, and Franklin County’s got a lot more man.”

But man oh man, do they pound the chorus, crying “Hallelujah” with real conviction “when Jesse’s head went under, ’cause this time he went under for the Lord.” You not only hear, but believe both sides of the story: old man and new man, prodigality and piety, sin and salvation. The simultaneous desire for and fear of drowning only works when you know what kind of man is being washed away, so it’s the gambling as much as the goodness that makes “The Baptism of Jesse Taylor” such a good song. A whole life lives in those verses because nothing is not worth mentioning, including “the county courthouse records [that] tell all there is to tell.”

Country Time is an occasional column about country music.

'Let Me Down Easy' in Order of Easiness

40. Sheppard

39. Saving Jane

38. Ronnie Laws

37. Rob Baird

36. Richard Page

35. The Bleachers

34. Nat Dunn

Free EPK from ReverbNation.com

33. 2AM Club

32. Exposé

31. Tompall and the Glaser Brothers

30. Van McCoy

29. Case

28. Cornelius Brothers and Sister Rose

27. Liquid Smoke

26. Paolo Nutini

25. Richie Davis

24. Mick Hucknall

23. Jeremih feat. Marcus French

22. Peggy Sue Webb

21. First Choice

20. Inez Foxx

19. Billy Currington

18. Rosemary Clooney

17. Spencer Davis Group

16. Rare Pleasure

15. G.C. Cameron

14. Lobo

13. Paloma Faith

12. The Stranglers

11. Chris Isaak

10. Cher

9. Sonny & Cher

8. Isley Brothers

7. Dennis Brown

6. Cold Blood

5. Dusty Springfield

4. Johnny Cash

3. Bettye LaVette, 1965

2. Little Milton

1. Bettye LaVette, 2012

The Startling Humanism of 'Mad Max: Fury Road'

The story of Mad Max: Fury Road centers on the escape of a harem of young women in a “war rig” driven by the unstoppable Imperator Furiosa, a splendid Amazon played by Charlize Theron, with the aid and counsel of Mad Max Rockatansky (Tom Hardy, glorious as usual). The women’s captors, a terrifying patri-army of punk-rock hot rodders and their leader, Immortan Joe, spend almost the whole movie in furious pursuit of the fugitives in the most explosively rip-roaring gasoline-spitting rocket-fueled action flick in about forever. But much of the critical conversation surrounding the film, which saw a respectable box office opening of forty-five million dollars, has centered on its gender politics.

Women are portrayed as warriors and survivors in this movie; on the other hand, the harem girls are so young, shapely and lovely and so scantily clad that they resemble nothing so much as a herd of supermodels waiting around for Steven Meisel. The women need Max’s help in order to escape their pursuers; on the other hand, he needs theirs. So there’s as much fodder for the Men’s Rights Activists at Reddit and elsewhere to complain about the weakening and “feminization” of Max (“Nobody barks orders to Mad Max”) as there is for Jezebel’s “Hysterical Man” to claim, “The New Mad Max Film Is So Feminist My Scrotum Killed Itself”.

A few days ago, Anita Sarkeesian and the shoal of fools that follows her around to yell at her constantly took to Twitter to contend over whether or not the movie is a feminist document. Sarkeesian says it is not, because, among other reasons, “Viewers get to feel good about hating cartoon misogyny without questioning themselves or examining how sexism actually works in our society,” and that while “Fury Road is different from many action films in that it lets some women participate as equal partners in a cinematic orgy of male violence[,] feminism doesn’t simply mean women getting to partake in typical badass ‘guy stuff.’” She thinks that “We’re starved for representations of powerful women but we need to re-imagine concepts of power & move beyond the glorification of violence.”

This is a profound misreading of the movie, but not for the reasons her opponents claim. There are two camps arrayed against these views: Loads of self-avowed feminists say that Yes, the movie is feminist, and they are happy about this, pointing to the power and authority of Furiosa throughout, to the agency and bravery of the fugitive brides, to the respect paid to the wise old Vuvalini, and to the cry, “We are not things.” (Much has also been made of the involvement of Eve Ensler as a consultant on the film, and that Miller’s wife, Margaret Sixel, edited the movie.)

In the opposite corner, the so-called men’s rights activists have gotten their knickers in a monstrous twist about the ruin of their favorite action classic by so-so-called Social Justice Warriors, because they don’t care for Social Justice, apparently, and prefer women to be things. Their misconceptions are hilarious for so many reasons, not least because Fury Road was directed and co-written by a seventy-year-old Australian man who explicitly told Vanity Fair, “I’ve gone from being very male dominant to being surrounded by magnificent women. I can’t help but be a feminist.”

The discussion around feminism has meant that so far, there has been little comment on Fury Road’s preoccupation with the evolution of men in recent decades. It’s a movie about how men and women can be not just “allies” to one another, as if our fates were separate, but real comrades, who must overthrow a common enemy and share a common fate. Instead, the balance of criticism has generally tended toward a defense against charges that Mad Max, the male protagonist, has been somehow weakened or made subservient to Theron’s Imperator Furiosa, who, with one arm, is the better shot — though not, perhaps, Max’s equal in raw survival instinct, because she is fighting for something more than survival. In this vein, the reliably excellent Sasha James observed: “Has [director George] Miller actually taken anything away? No. He has only allowed heroism in the Mad Max universe to be co-ed.” And that is certainly true. But however much he may share the lead role with Charlize Theron as Furiosa, Tom Hardy as Mad Max is still the heart and soul of this movie. It’s a real pity that that has gone unnoticed, because the deeper story has been ignored in favor of the feminist one. At bottom, Fury Road is a political allegory: The story of a revolution that ends with the overthrow of the ancien régime; it just so happens that the usurpers are mainly women. Perhaps the most compellingly real story is in the suggestion of how IRL young people can unite to cause the downfall of their oppressors — all of history’s oppressors — to take back the world and, though it will be super hard, establish a better and fairer humanity in place of the horrible old one.

And from another angle, the action revolves around three men: Immortan Joe, who represents the old patriarchy in all its grotesquely narcissistic, greedy, delusional excesses; Nux, who’s been exploited, poisoned and oppressed, but doesn’t see or understand that yet (he represents all the patriotic young kids who enlisted after 9/11 and then were hurt and disillusioned and ruined and disfigured in the eternal wars); and lastly our hero, Max, who’s known the score from the beginning and who has long been alone, a survivor haunted by his failure to save his own family. (There’s another sense in which you can see all three of these men as victims of a larger, inexorably pitiless machine; Immortan Joe, we see from the start, is not really so Immortan as all that, in his doomed attempts to move heaven and earth to maintain his position and in his pretensions to all-powerful abilities that he manifestly does not possess; this ultimate symbol of the patriarchy is a withering, dying old man, kept alive by broken technology. The old Freudian association of teeth with power enters in here: Immortan Joe’s teeth are assumed, not real, animal teeth, and the War Boys paint their teeth with chrome in a symbol of ersatz “hardening.” Max, whose mouth has been chained shut by Immortan Joe when the movie opens, can only act when the mask and chains come off; Joe dies only when his real, powerless mouth is exposed.)

All three men are altered by contact with women who’ve risked everything to reject the old order: The women imprisoned by Immortan Joe rise up to destroy him; Nux realizes that he’s been duped into volunteering himself as cannon fodder through the friendship of the women he’d come to capture and/or destroy; and Max, who has steadfastly avoided making a connection with any other human being, breaks down and shares his most precious bodily fluid with Furiosa — blood, to give her life. Max leaves her at the end of the movie, still the quiet loner who shows no emotions, the man whom the women ultimately needed to make it through, and there’s little that is progressive about that, in some sense. But I think he’ll be back.

In Max, we may read modern men in general, who were taught to fight and die and bleed for everyone else, uncomplainingly and alone, who were taught that women were weak, dependents to be “cherished” and protected — not equals who could fend for ourselves or fight side-by-side with them. But at some point in the late twentieth century, men somehow learned a different way of thinking about all that. What Miller is really doing is teaching men, not only women, how to rise above the patriarchy.

New York City, May 20, 2015

★★★★ The air conditioner had drowned out the soft buzzing of the phone alarm for an hour or more. Ivory-colored clouds drifted from west to east, separating till bright white light slapped the surfaces on Broadway. Downtown, the clouds were knitting back together. Once more it had been a mistake to go out without a jacket; it would have been superb jacket conditions — the month speeding by but the temperature refusing to hasten into summer. Brightness returned. The breeze filled the unfastened purple graduation gown of a young man slowly crossing Houston Street. Green maple samaras traced the foot of the churchyard wall on Prince Street. The sunset clouds were a rich magenta, flaring suddenly to shining pink, as a thin and ghostly crescent moon edged away from the glass apartment tower.

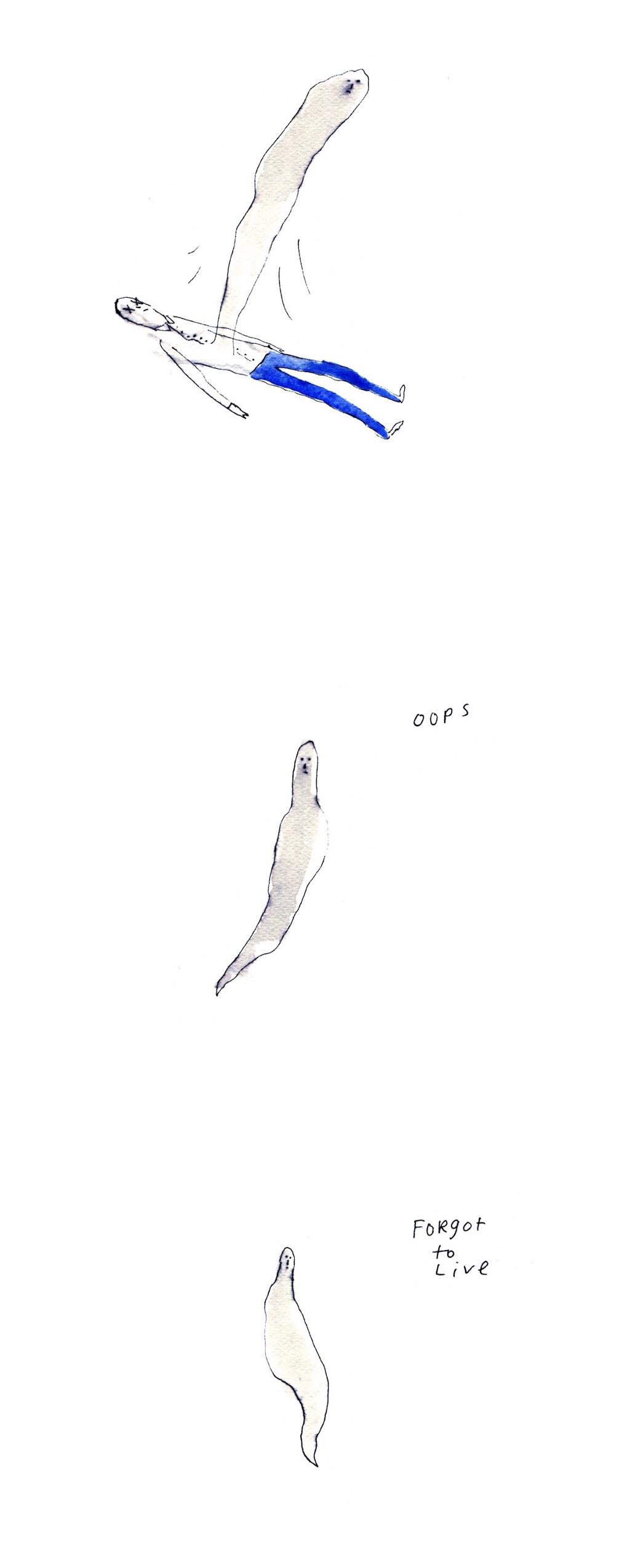

The Plan to Save Public Housing

by Brendan O’Connor

On Tuesday, in a gymnasium at the Johnson Houses in East Harlem, Mayor Bill De Blasio announced a new plan to revitalize and expand New York City’s public housing stock. Currently, more than half a million New Yorkers live in housing run by the New York City Housing Authority — nearly four hundred thousand in the city’s three hundred and thirty-four public housing developments, and another two hundred and thirty-five thousand in Section 8 housing. Founded in 1934, during the depths of the Great Depression, NYCHA began a long, slow slide into insolvency in the late eighties, as the federal government began divesting from public housing across the country. According to the New York Times, had earlier funding patterns held, the Authority would have received over a billion dollars more in federal funding than it actually has since 2001. They didn’t and it hasn’t, so the city’s public housing program is falling apart. “This is, at this moment, the worst financial crisis in the history of NYCHA,” De Blasio told dozens of reporters and a handful of tenants. “Literally the worst.”

The Authority’s buildings, more than three-quarters of which are over forty years old, require approximately seventeen billion dollars in unmet capital needs. “All types of repairs need to be done for the long haul, and the resources have not been there,” the mayor said. Moreover, “NYCHA has approximately one month of surplus cash on hand — one month, and after that will go into deficit.” If nothing is done, the mayor said, the housing authority’s deficit will build to two-and-a-half billion dollars over the next decade.

De Blasio bracketed his presentation of the plan to save NYCHA — branded NextGeneration NYCHA — with calls for the federal government to re-invest itself in affordable housing and infrastructure. “The federal government has to be much more of a key contributor again,” the mayor said. In response to a question regarding how much time he’s been spending away from New York City, the mayor said, “If you wanted the federal government to get back in the affordable housing business, one of the only ways to get there is with a more progressive tax system.” Last week, De Blasio traveled to Washington, D.C. to present a federal policy agenda with Senator Elizabeth Warren, and then to California to speak at UC-Berkeley with former Secretary of Labor Robert Reich. “I hold out the hope if we do that well, and if we join with cities around the country that we might be able to get more of the resources we have long been waiting for,” he added. (Many of New York’s mayors find their office taking them outside of the city: Michael Bloomberg, for example, spent many weekends in Bermuda.)

However, NYCHA’s current crisis can’t entirely be attributed to federal divestment: In December, Comptroller Scott Stringer found that NYCHA had, due to what he called a “culture of incompetence,” failed to collect on nearly seven hundred million dollars in federal and state incentives and subsidies. “NYCHA never acknowledges any of our audits. Never acknowledges there’s a problem,” Stringer told the New York Observer in April. “They are an embarrassment to government.” The new state budget, passed in March, authorized a hundred million dollars in funding for the Authority; the state funding is supplemented with another audit. Stringer’s office declined to comment on NextGeneration NYCHA.

The De Blasio administration has already taken steps to ameliorate the situation, cancelling a thirty-million-dollar annual tax payment the authority has had to make to the city since 1949, and absolving the authority’s responsibility to pay the NYPD $72.5 million annually for policing public housing properties. In addition to saving the Authority $4.6 billion in capital needs over the next ten years, the mayor argued that NextGeneration NYCHA will also create new revenue streams, leading to a two-hundred-and-thirty-million-dollar surplus. Among other things, NextGen NYCHA will enable the authority to increase the rate at which it collects rent — currently about fifty-four thousand households are delinquent — at a gain of thirty million dollars annually. It will also start charging as much as a hundred and fifty dollars per month for parking.

The cornerstone of the NextGeneration NYCHA plan, though, is the leasing of public land to private developers. This is not a new idea — the current administration’s plan is reminiscent of a Bloomberg proposal that De Blasio killed shortly after taking office — but the mayor alleges it will be executed in a new and more equitable way than previously envisioned. The Bloomberg plan, initially put forward in 2006, would have authorized developers to construct buildings on public land with a ratio of eighty percent market-rate apartments to twenty percent affordable units. (In 2008, as Manhattan borough president, Scott Stringer issued a report critical of the Bloomberg plan. “NYCHA’s development rights are a precious publicly owned resource — perhaps the last large-scale stock of public property in the city that could be leveraged toward meeting New York’s affordable housing needs,” the report reads. “Once these development rights are sold, they are gone forever. We owe it to ourselves, and especially to the public housing community, to look carefully before we leap.”)

Under NextGeneration NYCHA, however, the privately developed rentals built on leased public land will be available at very different rates: The mayor’s plan will create ten thousand new units in buildings that will be a hundred percent affordable, and another thirty-five hundred affordable units in buildings that will be fifty percent percent market-rate housing and fifty percent affordable. These units will count towards the mayor’s grander plan to build or preserve two hundred thousand units of affordable housing over the next decade.

This part of the mayor’s plan — a combination of a hundred percent affordable buildings and these 50:50 buildings — is supposed to generate five hundred million dollars in revenue for the Authority over ten years. The locations chosen will be very important. According to a report published by NYU’s Furman Center earlier this month, not all mixed-income housing will generate the same amount of revenue:

In strong markets, such as Downtown Brooklyn, a high-rise building with 302 units could generate approximately $2.24 million annually for NYCHA while maintaining 20 percent of the units as affordable. If NYCHA chose to forego a ground lease payment and instead maximized the number of affordable units, 47.5 percent of the units in this new high-rise development could be affordable to low-income households without any additional subsidy. A compromise approach could result in an annual ground lease payment of $1.48 million to NYCHA with 30 percent of the units affordable to low-income households.

The capacity to lease NYCHA land to generate value in the form of affordable units or ground lease payments is much lower in parts of the city with lower rents. In an area with moderate rents, such as Astoria, a mid-rise development with 20 percent of the units affordable to low-income households would only generate an annual lease payment of $117,000 for NYCHA. Even with no lease payment, that development could only support making 26 percent of its units affordable to low-income households.

An earlier Furman Center study, from March, was specifically critical of the administration’s plans to facilitate affordable development in lower-rent areas like East New York and the Jerome Avenue corridor in the Bronx by allowing for zoning variances that would increase buildings’ height. The report argues that you can increase height — and therefore density — all you want, but in such areas, developers simply aren’t going to be able to charge enough in rent to cover the costs of construction. “If you’re in Union Square you can build anything you want because the rents pay for it,” David Kramer, a developer at Hudson Companies, which builds both affordable and market-rate housing, told the Wall Street Journal. “Then you go out to Astoria and you can’t be too fancy. Then you go to East New York and there’s no new construction of market-rate housing at all.” (The average rent for a one-bedroom apartment in Astoria in April was over two thousand dollars per month.)

This, then, is at least one argument in favor of renewing the 421a state tax abatement — which reduces property taxes for a set period of time (usually ten years) — that developers receive for building on underused or unused land: Without 421a, set to expire in June, some developers say they won’t be able to build affordable housing in lower-rent neighborhoods at all. But tax abatements for developers don’t really make the city a more affordable place to live in — they make the city a more affordable place to build in. Rents have continued to rise, and people continue to move further out from the city center. Unless, of course, the present abatements were revised to require that more housing in a given building was “affordable” in order to qualify for a tax break. Another solution would be to focus the search for underutilized NYCHA property in higher-rent neighborhoods, where the revenues from market-rate units in mixed-income buildings would be maximized; rising rents all over the city, but particularly in these neighborhoods, would allow developers to charge more for the market-rate units.

Of course, if rents weren’t rising so dramatically, the government wouldn’t need to subsidize private developers to build such highly sought-after affordable housing for the city’s increasingly overburdened working class in the first place.

Top photo by Edward Banks

Ass So Fat...

by Sam Stecklow

I might take a vacation1

You would’ve thought it was bogus2

I seen it with my pimp view vision3

Need it softest4

She need lipo5

I’m crying anti-depressants6

Her cheeks were jolly7

It tipped over the Aston8

It was built in a factory9

No butt pad10

Should’ve YOLO’d twice11

Make me wanna dive in it12

It’s popping out my jeans13

Let’s make a baby14

You can ride me like a stable horse15

Man, I swear I can’t even speak16

I just wanna hocus-pocus abracadabra that17

Make a player wanna smash that18

How you support all that?19

You could park ten Tahoes on it20

4. Red Cafe, “Making Me Proud”

5.Joyner Lucas, “Look Around Me”

6. Mykki Blanco, “Angggry Byrdz”

14. Wiz Khalifa, “We Dem Boyz”

17. Lunar, “What You Twerkin With”

A Poem by Catie Rosemurgy

by Mark Bibbins, Editor

In Which Blame Like Formaldehyde Is an Attempt to Preserve the Dead

In which composite of bad things

In which grown up huge from seed

In which I don’t know who is speaking

In which why do you think I would?

In which what happened and what didn’t switch places

In which in that way a girl matters

In which first the tart and then the lemon

In which first the burning and then the witches

In which density of the forest

In which small ones don’t get enough light

In which dead ones stand for years held up by the living ones around them

In which women refuse to be named

In which guessing is a pattern called Seven Sisters

In which whoever told you metaphor is figurative?

In which what happened props up one end of a wooden plank

and what didn’t props up the other

In which the surface isn’t quite even

In which I put the bad ideas in mason jars that I tie with twine and hang across my porch

In which women become interchangeable as an adaptive advantage

In which like the crayfish’s exoskeleton

In which both make a noise when crushed

In which I forget how to phrase things as questions

In which metaphor is the scissors and the glue

In which you are cut into an arrow-shape and hung as road sign

In which trees actually do matter

In which no one prunes a whole forest

In which fire does

In which you are already too large to be dug up and replanted into good soil

Catie Rosemurgy is the author of two collections of poetry, My Favorite Apocalypse and The Stranger Manual, both published by Graywolf Press. She lives in Philadelphia and teaches at The College of New Jersey.

You will find more poems here. You may contact the editor at poems@theawl.com.

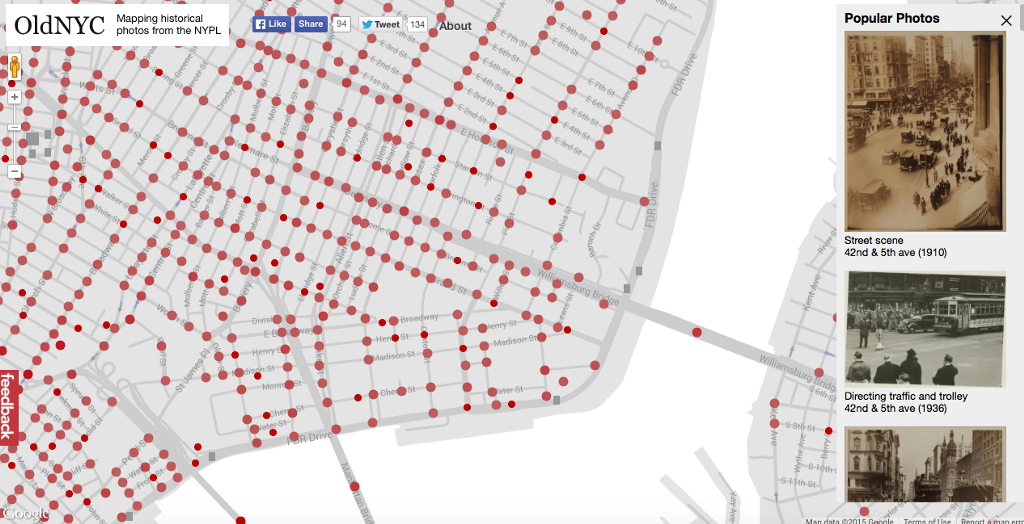

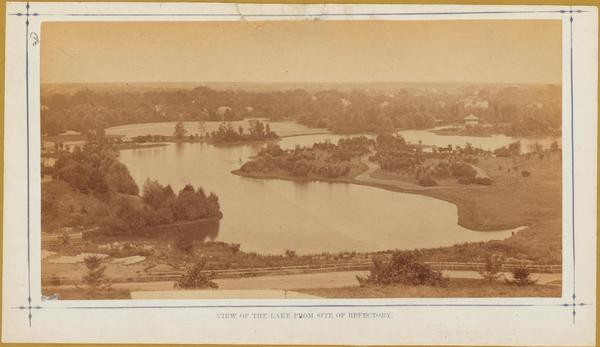

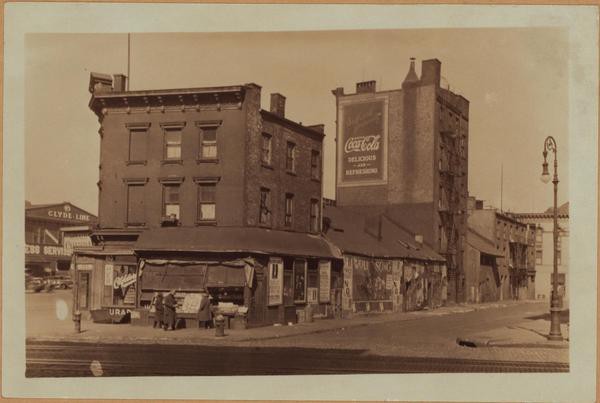

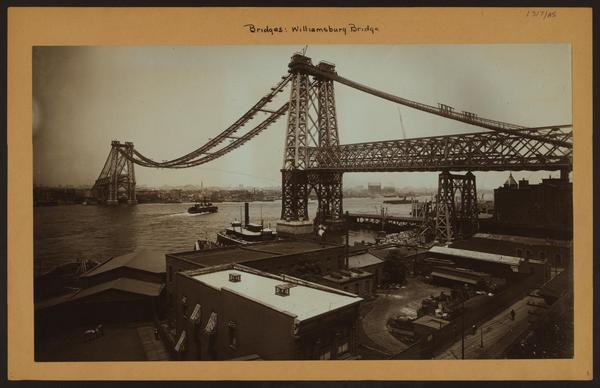

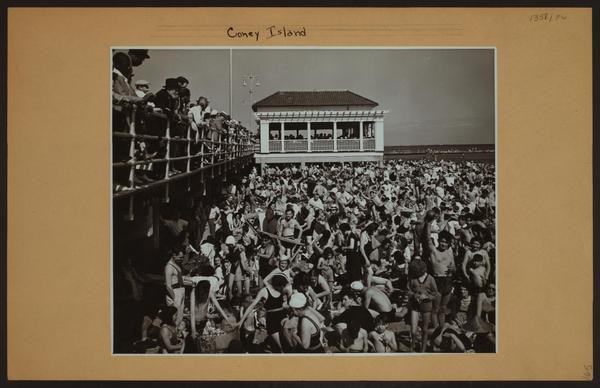

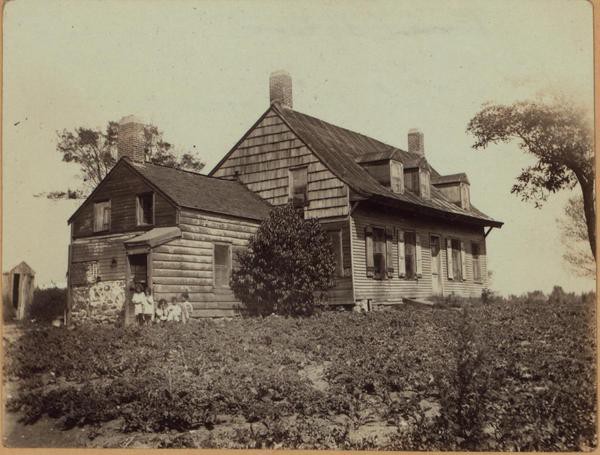

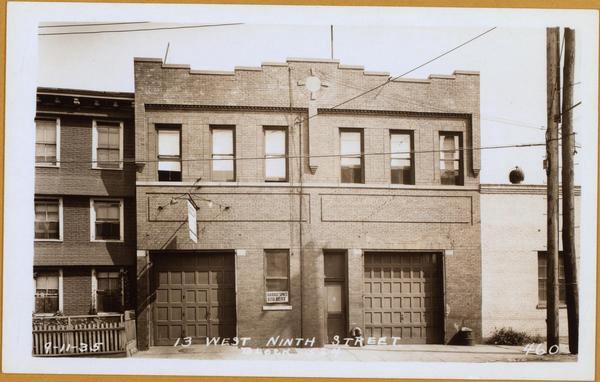

Old New York, Mapped

The New York Public Library’s massive collection of historical city photography has been mapped:

This site provides an alternative way of browsing the NYPL’s incredible Photographic Views of New York City, 1870s-1970s collection. Its goal is to help you discover the history behind the places you see every day.

And, if you’re lucky, maybe you’ll even discover something about New York’s rich past that you never knew before!

This is a rare and excellent internet object; a fascinating but unapproachable collection of media made approachable. I RECOMMEND IT, it is a powerful time-waster that asks for nothing in return. Mmmmm. A few tastes:

Tearing down the 6th Ave El at 42nd Street, 1939.

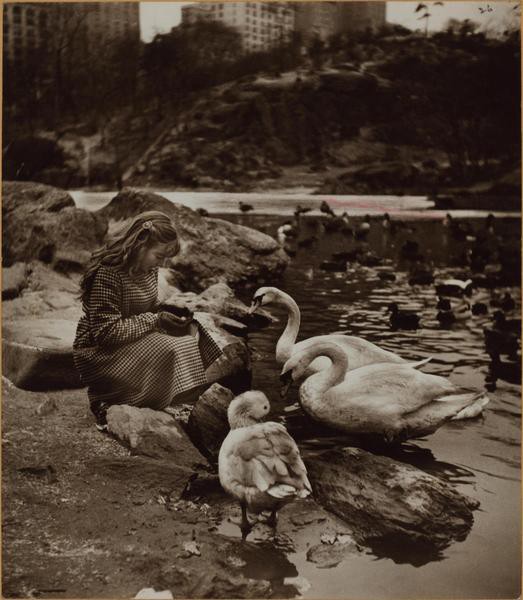

The mud-eating trash birds of Central Park, 1938.

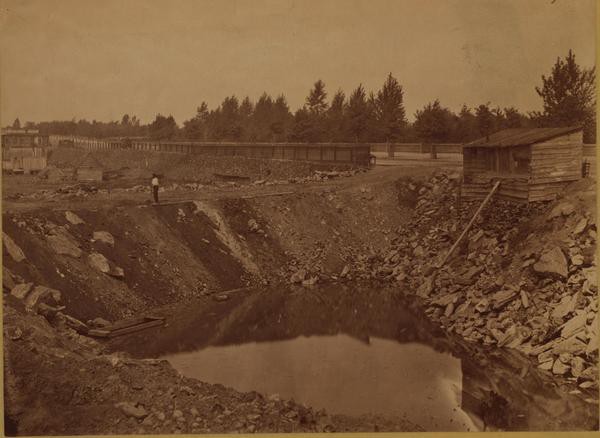

The beautiful view from what would become some of America’s most expensive real estate, at Central Park near 59th Street, 1870.

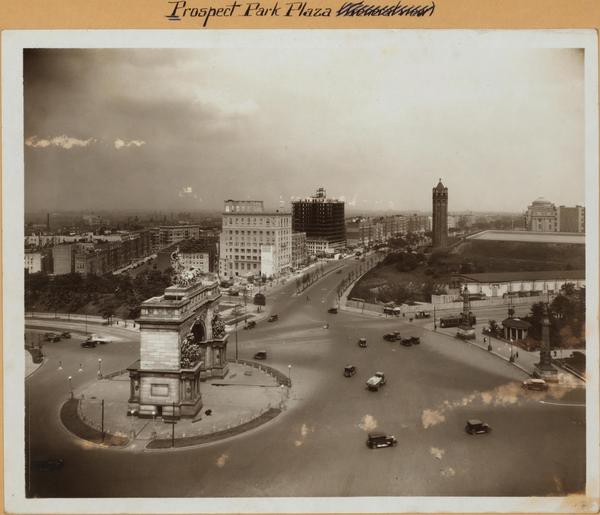

Grand Army Plaza near Prospect Park, 1926.

Empty quiet Prospect Park, 1880.

West Village, 1927.

Broadway and 34th, who knows but before the El died. There were so many trains! There were also so many apartment windows that were like 20ft from these trains.

Groceries, 9th and 40th, 1936.

Williamsburg Bridge, not done, ~1903.

Wall Street, ~1900, plotting a century of serial crime.

Relaxing day at Coney Island, body-positive, 1939.

Future site of JFK Internaional Airport and Security Checkpoint, 1922.

The creation of Very Long And Skinny Park in the LES, 1932.

Gowanus looking familiar, 1935.

Most of the locations have multiple photos, so the collection is much bigger than it first looks on the map. Anyway it’s great, spend a while clicking around.