New York City, May 19, 2015

★★★ Fog again, a chill again. Birds had sung, loudly, through the open window in the dark hours of the night. It was time to drag the beds and the couch away from the heating-and-cooling cabinets so the crew could come in and change the filters. A few streaks of rain hit the windows around midday. It was a little too muggy out in the drizzle for the jacket, and a little too chilly to be without it. Amid the uncertainty, the air conditioning on the train was surely the wrong temperature. In the afternoon, the sun came out, or a blinding sunlike field of glare came out. The sky opposite it was blue, with a haze that only amounted to cloudlike streaks here and there. The hazy glare made its way west and grew yellower. A jet flew through it with an ooze and a flash like a bubble in shampoo. The first mosquito of the year flew into the living room, drifted under the neck of the little blue guitar, and allowed itself to be killed against the hassock.

Friedan's Village

by Marina Budhos

Long before Betty Friedan gave voice to American women’s discontent in her groundbreaking classic, The Feminine Mystique, she was a young mother and wife living in Parkway Village, a tiny, planned garden apartment complex in Queens, New York. This vanguard utopian, international, and interracial community served as her incubator and muse, allowing Friedan to rethink the norm for post-war American families. I grew up there, and though Friedan departed eight years before my family moved in, she was so legendary that I was sure she lived across from me, her parties spilling onto her patio.

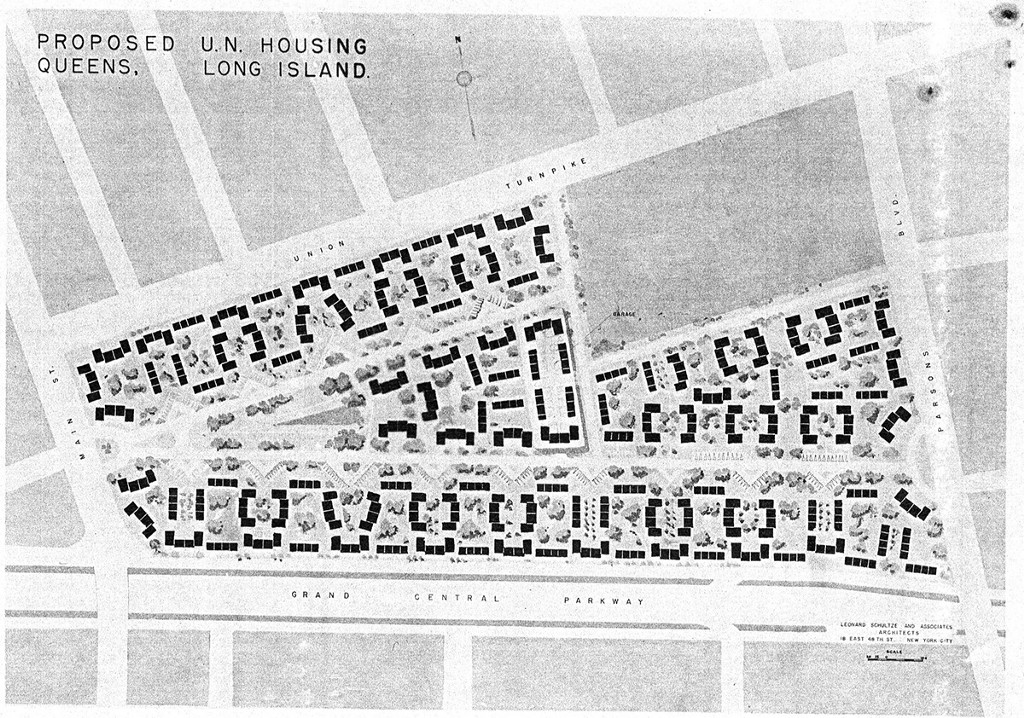

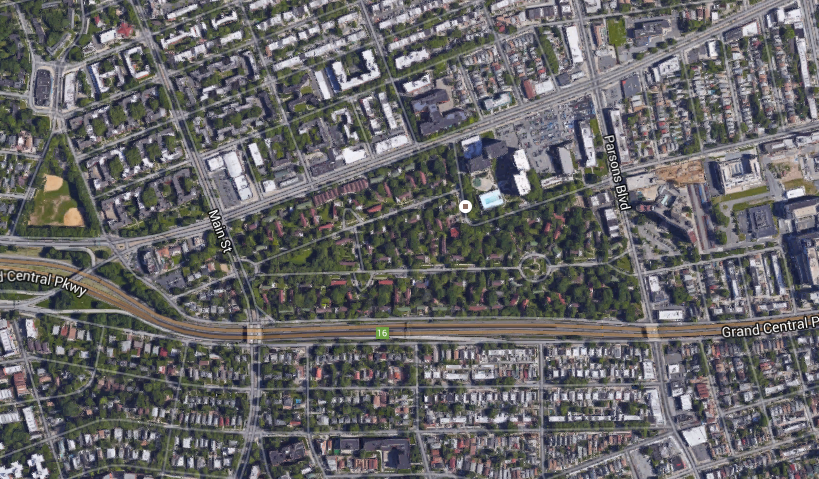

Built after World War II, Parkway Village was the brainchild of Robert Moses: a forty-acre enclave of garden apartments for foreign United Nations employees, many of whom could not find housing because of racial discrimination. Unlike other huge developments that explicitly forbid people of color, such as Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village, Parkway Village was open to all races, because no housing for UN employees could violate the UN Charter, which required no “distinction as to race, sex, language, or religion.”

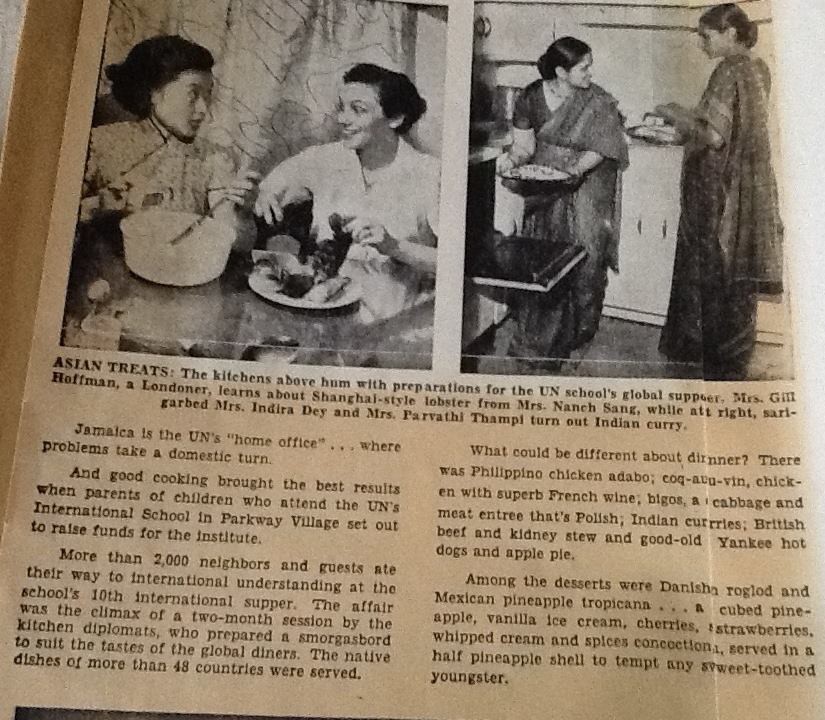

As a result, Parkway blossomed into an oasis of racial integration and international cooperation that was profiled in newspapers and magazines like the New York Times and Collier’s, which characterized it as “living proof” that the ideals of the UN “can work out on Main Street.” Ralph Bunche, the first man of color to win a Nobel Peace Prize lived there, as did Roy Wilkins, head of the NAACP, as well as Babe Ruth’s widow, who was known to give nice tips and hot chocolate to the boys who shoveled her walk. Eleanor Roosevelt and Margaret Truman came to visit the cooperative nursery school; Paul Robeson’s wife used to show up for parties. The local children were gathered and photographed for the cover of a seminal jazz album, Evolution of the Blues. And Latin American author Ariel Dorfman would remember Parkway Village as an international paradise, before McCarthyism drove his leftist father out of the UN and the country.

Friedan wound up in Parkway because she spotted a notice in a newspaper that the community had apartments for ex-GIs and newspaper correspondents. During a lunch hour at her job, she took the subway out and was so enchanted by the enclave and its spirit of equality that she convinced others to join them, such as Dick Carter, an award-winning journalist who would become the biographer of Jonas Salk. Once in Parkway, through the International Nursery School, their circle would quickly extend to William Jovanovich, the unconventional and daring publisher of Harcourt, Brace & Jovanovich, and Tom Wolf, later vice president at ABC News. These couples — young, liberal, and creative — formed a kind of quasi-commune, sharing meals, creating a babysitting pool, children running in and out of the shared yards. “I loved the concrete daily life of that community … the politics of it, the bonds we formed with other parents at the nursery school,” Friedan wrote in her memoir Life So Far. “We became an extended family for each other, but we also made close friends with Mexican and Iranian families, and French and Swiss we met. All of us were so happy in that community.”

What Friedan experienced was a product of the physical layout of the village, which had been designed by Leonard Schultze and Associates, an architecture firm known for their planning of post-war “cities within cities,” which drew from the tradition of the “garden city” movement in England. Garden cities were seen by urban planners and architects as a way to reinvigorate city living, offering many of the amenities of the suburbs — grassy, open space — while serving a segment of the urban middle class that rejected private home ownership. These were self-contained communities featuring a careful sculpting of the landscape around two-to-three-story buildings that were set within green spaces. Similar communities were built in Queens — Sunnyside Gardens, Jackson Heights, and Forest Hills Gardens — standing in contrast to both the huge, multi-story apartment complexes being built in the city and the individual homes multiplying in suburban Levittowns.

In the village, long apartments opened on to large, shared yards and courtyards and playgrounds, with the complex centered around a large village green. The only place I have ever visited that resembled Parkway was a kibbutz. And while Parkway did not have the extensive communal activities and structures of a kibbutz (though there were lots of organizing activities around playgrounds and international festivals), there was a feeling that every home was everyone’s home. For parents, to live here meant a kind of giving over, as children ran up and down the winding paths, in and out of apartments. When I grew up there, the general rule was that we could roam as far and wide as wanted inside of the village, so long as we came home when the street lamps blinked on. Even then, in the spring and summer evenings, there were so many adult gatherings, that most of us would bolt outside again, comforted by the sound of tinkling and adult voices shifting through the trees.

The most common critique of Friedan and First Wave feminists is that they were really only speaking for white, middle-class, educated stay-at-home housewives, but Friedan’s ideas were first inspired by her interaction in Parkway Village with women from very different backgrounds and countries. During that early period in Parkway, as she developed her brand of feminism, she was not writing from the mainstream center of America, but from a slightly Bohemian vantage which broke down the isolated existence of the housewife, allowing her to stand back to critique American womanhood and begin to imagine other possibilities.

As historian Daniel Horowitz has noted, after being fired from a union news agency when she became pregnant with her second child — a story that was often told by Friedan in later years as a turning point in her developing feminism — she transformed The Villager, Parkway’s local newsletter, into a vigorous outlet, profiling foreign women who offered a different vision of womanhood, working at careers, organizing politically, and knowing how to rely on networks of other women — while making sure their husbands did their share of domestic duties. Of a Filipino resident with six children, Friedan wrote: “American women who find it difficult to combine a career with even one or two children could learn from Mrs. Mendez, who got her children and diplomat husband to do much of the housework.” In another article, Friedan revealed that women from abroad often felt sorry for American women “whose lives were severely restricted by their obligations as homemakers and mothers.” Parkway was the alternative that Friedan glimpsed: not the nuclear family that locked housewives into numbing isolation, but a place of patios and conversation, of women of all nationalities sharing childcare and dishes across the yards.

In 1952, Friedan helped to lead a tenant’s strike, which was sparked by a proposed rent hike that threatened to capsize the community. Friedan and her fellow activists fired off telegrams to President Truman and the presidential candidates; they argued that Parkway Village was an example that could be expanded on a large scale, and that it represented our hope for raising a new generation of children, free from prejudice. Major political figures were enlisted in the fight, including Jacob Javits and Nathan Straus, the former US Commissioner on Housing. The tenants’ fight was covered by many newspapers, and even made it to the New York Times editorial pages, with a plea to save “this living example that the peoples of the world can live harmoniously together.” The group succeeded in a temporary stay, and then the landlords agreed to modified rent increase — sixteen percent, as opposed to the originally proposed thirty-two percent.

In 1956, Friedan and her husband went in search of more space for their growing family. They tried, valiantly, to re-enact the paradise they had found, scheming with Parkway friends and UN officials to buy land up the Hudson to build, as Friedan wrote, their own “truly future-minded cooperative, each with our own houses, a common library, pool, tennis court, as well as a nursery school.” The plan failed, as it “came up against violent opposition,” when local authorities discovered their “dream of a utopian international community” would be interracial.

The Friedans’ eventual home in Rockland County was hardly a faceless suburban subdivision. Set against the rugged bluffs of the Palisades, thirty minutes outside New York City, the Nyack area was also a Bohemian outpost, similar to Parkway Village, with its own storied history of artists and theater and film personalities. (My husband’s parents, Broadway set designers, would eventually build a house there; from their living room, I can see straight down to River Road, where Friedan would eventually pen The Feminine Mystique in a rambling Victorian.) Staying home with three young children, Friedan would regret their decision to leave Parkway — “I felt that I would never again, ever, be so happy as I was living in Queens,” she remarked in It Changed My Life, her personal history of the women’s movement. That ache of frustration and loss would partly impel her later monumental work, The Feminine Mystique. “I realized later that the kinds of community bonds that had sustained our otherwise ‘dysfunctional family’ in Parkway Village … were more important than an extra bedroom and a view of the Hudson River.”

A photo of Marina in Parkway Village, age six

Friedan’s earlier Parkway vision of raising the next generation of children free of prejudice largely came true. My family moved from Hollis, Queens, into Parkway Village in 1964, one year after The Feminist Mystique was published. We had fled a racially homogenous neighborhood, where the police once showed up at our door to report “the black man that was on our lawn” — my father, a dark-skinned Indian immigrant; we took over the apartment from one of the original GI families, who were retiring to Florida. As I was growing up, all over our community, in those airy apartments, mothers enacted Friedan’s revolution: They marched for peace and women’s rights; some pushed integration plans in the public schools, as if to mold our surrounding, neighborhoods into Parkway’s image. (The plan backfired during the tumult of the 1968 teacher’s strike and the racial splits of the time) They went back to school; they started the first women’s center in the borough of Queens; they divorced; they moved elsewhere, started again, and remade their lives.

By the early seventies, the social upheavals that were sweeping the nation crashed right into Parkway, where the counter-culture bloomed — impromptu rock bands playing on the Green, high schoolers holding radical meetings in the basement laundry rooms. But there was an undertow to all this change. Parents separated, were increasingly absent, leaving empty apartments to become havens for lots of risky teenage experimentation. As a private community, we were off-limits to the police, so the Green became an open drug market. Stories of drug overdoses, dropping out, were not uncommon. By the mid-seventies the city was bankrupt, the public schools troubled, and more middle-class families were leaving. A few staunch Parkway Villagers moved out — some to the suburbs, others to a new complex in Manhattan, Waterside Towers, which had opened up next to the United Nations International School.

In the eighties, the complex was converted to a co-op, making it harder to continue that same social cohesion that I experienced growing up. Yet its legacy endures: Friedan’s early motherhood and my childhood in Parkway remind us of a time when cities looked to intentionally engineer middle-class living. That backbone of post-war middle-class rental stock was crucial to the New York City of the fifties and sixties — it kept not just firefighters and nurses and teachers within the city limits, but the creative class, too. Parkway Village stretched that idea further — to racial integration and international cosmopolitanism. Given how racially divided the city during Parkway’s early decades, it was a radical notion. It meant that for children like me, the children of Friedan, the social order looked different than the rest of America; we carried within us a vision of what it might mean to live in a more mixed and equitable world.

All photos — except the final one — courtesy Marina Budhos; diagram via the Parkway Village Historical Society

Read an Excerpt From Kirsty Logan's 'The Gracekeepers'

by Awl Sponsors

Presented by Penguin Random House. Purchase The Gracekeepers here

.

The first Callanish knew of the Circus Excalibur was the striped silk of their sails against the gray sky. They approached her tiny island in convoy: the main boat with its bobbing trail of canvas-covered coracles following like ducklings, chained in an obedient line. Ships arrived a dozen a day in the archipelagos, and Callanish knew that the circus folk would have to fight for their place on her island. Tomorrow the dock would be needed for a messenger boat, or a crime crew, or a medic. In a world that is almost entirely sea, placing your feet on land was a privilege that must be earned.

As dusk fell, Callanish loitered at the blackshore, her slippered feet restless on the wooden slats. She watched as the circus crew spilled ashore: a red-faced barrel of a man, trailed by a bird-delicate boy; a trio of tattooed

ladies, hair bright as petals; two gleaming horses left to gum at the seaweed. To a chorus of shouts — hoist! hoist! hoist! — the crew pulled ropes in unison, their limbs slick with saltwater.

Callanish tugged at her white gloves as she watched the circus unfold. She saw how the boat’s sails would become the striped ceiling of the big top; how the wide, flat deck would be the stage. With each billow of sail or tightening of ropes, she inched further off the dock and on to the shore. It was only when the sun dipped below the horizon that she felt the damp chill in her toes and saw how her slippers had darkened with seawater. Oh, she would be in trouble now.

She ran home doing giant steps, leaping high into the air like a circus acrobat, hoping the wind would dry her slippers before her mother saw.

That night Callanish huddled under the striped canopy, mouth open as she gazed up, gloved hands gripped between her knees. Not all the landlockers on her island found the circus a glad sight: there were enough people on the island to crowd out the big top twice over, but it was only half full. Still, Callanish was excited

enough for every single landlocker in the whole archipelago.

Her mother had scrubbed and scrubbed at the white silk slippers, muttering that Callanish would have to skip the performance. Callanish had shut herself in the wooden chest, hiding among the sealskins, until her mother relented. She promised that she would not fiddle with her gloves and slippers, and she would be silent and good and unnoticed, and it would all be worth it for the circus.

“We shouldn’t welcome damplings like this,” murmured Callanish’s mother, folding her bare hands on her lap. “And at nighttime too, when good people should be tucked up safe in their houses! What are those circus folk hiding in the dark, hmm?” She patted Callanish’s hands, making sure the gloves were on. “Some islands don’t even let damplings come above the blackshore. If they want to perform, they can do it in the daytime with waves lapping at their ankles like they’re meant. Those people belong in the water. They’re dirtying the land.”

But Callanish knew that would never work. The circus would not look good in the bland, bright day: its colors would fade against the clouds, spitty rain would threaten the fire-breather, the acrobats’ sodden feet would make them shiver so much they missed their catches. What would be the point of an imperfect circus?

The red-faced barrel-man strode onstage, dressed in a ringmaster’s costume of an elaborate hat, black trousers, and a shirt covered in rows of paper ruffles. Even Callanish’s mother gasped at that: so much paper must have cost a fortune.

At the ringmaster’s urging the circus burst into colors, lights, the death-mocking glory of twists and catches and bright gleams of skin. To Callanish it felt more daring than secrets, more vivid than memory, and her eyes opened wide as eggs. After each act — acrobats! horses! fire-breathers! — the landlockers rushed to fill the ringmaster’s hat with lumps of gold and coal and quartz and copper. By the time he was introducing the final act, he had to drag his treasure-filled hat offstage.

On to the stage stepped a family: a man and a woman with a girl of about Callanish’s age. They were all dark-haired and draped in fabric, pure white and shimmering. The woman held one end of a golden chain, the other end hidden behind a curtain. They bowed to the crowd, then the woman tugged the chain. An enormous shadow lumbered toward her.

“A bear!” cried out Callanish. “From the storybook! A bear and a baby bear!” And sure enough, padding unsteadily in the big bear’s wake, came a bear no bigger than Callanish.

Offstage, a needle whined on to a record. Violins swooped around the big top. The man and woman began to dance. They waltzed around the golden-chained bear as it reached its heavy paws out for them, at first in play, then in frustration. The song eased into another rhythm, and the woman slipped away from the man and into the bear’s grasp. The crowd gasped, shrieked, stood as if to run — but the bear was turning and stepping gracefully, its paws clasping the woman’s hands. They were dancing. After a moment, the little girl and the little bear joined hands and danced too, a mirror in miniature. Callanish clapped with glee, and even her mother seemed charmed.

In the years that followed, Callanish tried many times to remember exactly what happened next. It did not help that as

soon as the big bear roared, her mother wrapped her arms around Callanish’s head and pulled her close, the world instantly reduced to the earthy, floral smell of her mother’s skin and the scratchy wool of her dress. But Callanish could still hear the screams, the roars, the chaos of running feet. She felt herself lifted as her mother hefted her on to her hip and ran.

Jolting with movement, Callanish fought to peer back over her mother’s shoulder. She saw landlockers scrambling to the exits. She saw the dropped bodies of the man and woman, their white clothing stained dark, their skin sheened red. She saw the bright gleam of a blade in the woman’s motionless hand. She saw the big bear, belly sliced open, a shadow heaving its final breaths. And in the center of it all she saw two figures: one draped in white, one furred black; both with eyes open moon-round and empty. A small girl and a small bear, hands and paws still linked.

The Quantified Baby

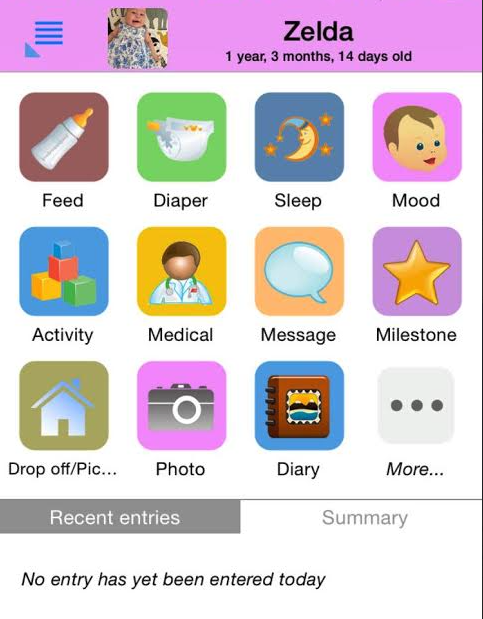

Last week, I was sitting on the couch at the end of a long day. I had an itch. I pulled out my phone. I opened my email, nothing new; Instagram, no baby photos to post; I didn’t even bother opening Twitter. “Oh right, Baby Connect,” I said to myself. I opened the app, which I have used to track Zelda’s sleeping and eating since she was just a few months old, and saw its familiar home screen. No recent entries. For three days, I had entered nothing. A new phase of life, one where my daughter’s sleep-wake cycles are quantified only our heads, had begun.

I didn’t come to obsessively tracking her with an app purposefully: It happened, almost, by accident. But I am a controlling, note-taking kind of person, so it shouldn’t surprise anyone that it happened. When I began consciously trying to put my daughter on a sleeping schedule, she was just four weeks old. In the first four weeks of her life, we had rolled with the punches, trying to pretend she was sleeping when we wanted to be asleep, and watching with wonder her capacity for daytime snoozing during all manner of racket. But by the time that month had passed we were exhausted, and having read a book called The Baby Whisperer in desperate moments of lucidity, I decided to try to nudge her toward a more human way of sleeping.

The Baby Whisperer (who is sadly RIP) suggested that the link between a baby’s eating and sleeping were all-important, and that, therefore, the most important thing was to know precisely when they eat and sleep. Doesn’t sound particularly revolutionary, but in the earliest days of parenting, I couldn’t have told you how many times a day my baby ate: Ten? Five hundred? When she cried, we fed her. That often seemed to work but it made for a lot of confusion. The Baby Whisperer claimed that if I knew how often she ate, I would begin to see patterns, and patterns, she went on, were the key to knowing when your baby was tired.

So I did what she suggested: I got a notebook. I began writing down every feeding, every time she went to sleep, and every time she woke up. At the earliest point, based on her age — four or five weeks — the chart in the book said she would probably need to sleep after being awake for an hour and a half. On paper, doing the math was sort of complicated: She woke at eight, needed to sleep again ninety minutes later. But she actually went to sleep seventy-five minutes later. Then she should have slept for an hour-and-a-half, but she actually slept for twenty-six minutes, so… when should she sleep again? In an hour-and-a-half? I still have these notebooks. They are horrific enough that I try not to look at them. One day often took three full pages of calculations, and at times, my husband would say, “This is insane, what are you doing? Why are you trying to force her onto a schedule like this?” And he was right — it seemed nuts. But I wasn’t REALLY forcing her. I was just observing, writing everything down.

Patterns did emerge, and her sleeping and eating started to look more like the chart in the book, until it eventually looked almost EXACTLY like the chart. I also noted that her moods seemed dramatically improved; she stopped crying so much. This was enough encouragement for me.

When Zelda was about four months old, we hired a nanny to come a few days a week. I needed to go to the dentist and the doctor, and I was thinking about working. She was on board with the concept of the baby’s schedule from the moment I met her, which was one of the many, many reasons I liked her so much. Val understood how important Zelda’s “good sleeping” was to me. She understood that I didn’t subscribe to the “never wake a sleeping baby” theory because I wanted her to sleep allllll the way through the night, so I often woke her after she’d been sleeping for just an hour. I showed her the pad of paper where I tracked everything. I tried to explain my, by now, extremely annoying system of marks and symbols.

Val suggested, almost immediately, an app she had used with other families: Baby Connect. It tracked everything just as I was doing, but on your phone. I wouldn’t have to add up each nap and nighttime sleep at the beginning of each day (which, in hindsight, definitely seems borderline insane); it would track all that for me. It would also track when she ate, and how much. I said something like, “Okay neat, I’ll check it out,” but inside, I revolted. I was attached to my paper system. A goddamned iPhone app?

I downloaded it anyway. I added myself, and my husband, and Val. Almost immediately, I could see the advantages, despite its clearly lacking design sense and interface. If I wasn’t around, I could open the app and see when she was sleeping, assuming whoever was with her had updated it. But updating it was easy: Open the app, push the button that says “sleeping,” and the timer begins. No more looking at the clock, no more doing the math in my head. “She’s been asleep for forty-seven minutes.”

We switched over to the app easily. I could see how much she’d slept in a day, a week, or a month, in charts or bar graphs. I could see how much she was eating — and back then, when she only “ate” milk, it seemed to matter so much. My life seemed to get easier. And though Zelda was pretty consistent, tracking her variances of a few minutes or an hour each day gave me a sense of control — not over her, but over myself. I could let go, just a little. I didn’t have to do so much math in my head. I could forget exactly when she went to bed, as long as I hit the button on the way out of the door of her room.

It became a reflex, something I didn’t think about. Until I noticed last week, that after almost sixteen months, I’d stopped. I had weaned myself from tracking her food slowly, around her first birthday, as Zelda drank less and less milk and ate more and more food within the general framework of three meals a day. Val and I agreed: It didn’t make much sense anymore to say, “Yes, she had lunch.” Of course she did. But I continued to cling to the sleep tracking, partly because it was still the most volatile day-maker/breaker: If something wakes her up from a nap after forty-five minutes when it usually lasts two or more hours, it’s going to show in her demeanor. So every day, we hit the button at night. We hit it when she woke up in the morning. We hit it again when she went down for, and got up from, first three, then two, and finally now one nap. We tracked all of it. Day in, day out, so that I know how long she slept on my birthday last year — fourteen hours and fifteen minutes; or Josh’s — thirteen hours and forty minutes; or on New Year’s Eve — thirteen hours and sixteen minutes. I know that she slept four hundred and forty hours in both December and January. None of this, in hindsight, is useful. But in the moment, it certainly felt like it was.

In the first year of a baby’s life, there is a lot of talk of milestones. Milestones increase over time in their impressiveness, starting with the almost humorously sad: the first time the baby lifts its head, or rolls over. Then they sit up, crawl, and walk. I didn’t encourage much of anything, and Zelda still seemed to develop generally along the same lines as most other babies — most of the major events happening when I was least expecting them, and least prepared. We rolled with the punches each day, forgetting quickly that just a few weeks ago, she couldn’t hold up her head or wave.

Now I’ve rolled through my own milestone. The itch is gone. I needed desperately to track every moment my daughter slept, until I didn’t. These days, Zelda applauds me when I pick up her toys or wipe off the tray of her high chair: She knows I’m accomplishing something and she wants me to know she thinks I’m doing a good job. I assume (or hope) that if she knew that I was obsessively tracking her sleeping and eating for the past sixteen months but suddenly and without warning went cold turkey one random night last week, she might clap then too.

That Mbongwana Star Record Is Good And You Should Listen To It

There’s a lot going on in Mbongwana Star’s From Kinshasa, so much so that it’s probably best if you listen to the whole thing yourself and decide whether or not it’s for you. The entire album is available below. At least give your attention to the first two tracks, they should provide a fairly fine indication of how well you will enjoy the rest. And hopefully what you will indeed do is enjoy.

Fancy New Robot Desk Will Tell You When To Eat, Shit

“Walk into work in the morning, and the new Autonomous Desk pops up to a standing position. Later, you can adjust it to take a sitting break, but if you sit for too many hours, the desk is going to remind you to stand up again. In the meantime, you can ask the AI-powered desk to order you lunch, set a couple of meetings, and adjust the temperature on your Nest Thermostat.” Also: “You can think of the desk as a personal fitness trainer.”

New York City, May 18, 2015

★★ Fog took away height and distance, then slowly lifted off with no diminishment of the overall grayness. The 1 platform was stifling; the train countdown clocks went backward by three minutes. Up on Broadway again, $2.75 wasted, the breeze was an immediate relief. The dimness of late afternoon was no different from the dimness of morning or midday. Only the clouds had changed, to a firm mottled ceiling, sliding past the buildings a little faster than walking would have made it move.

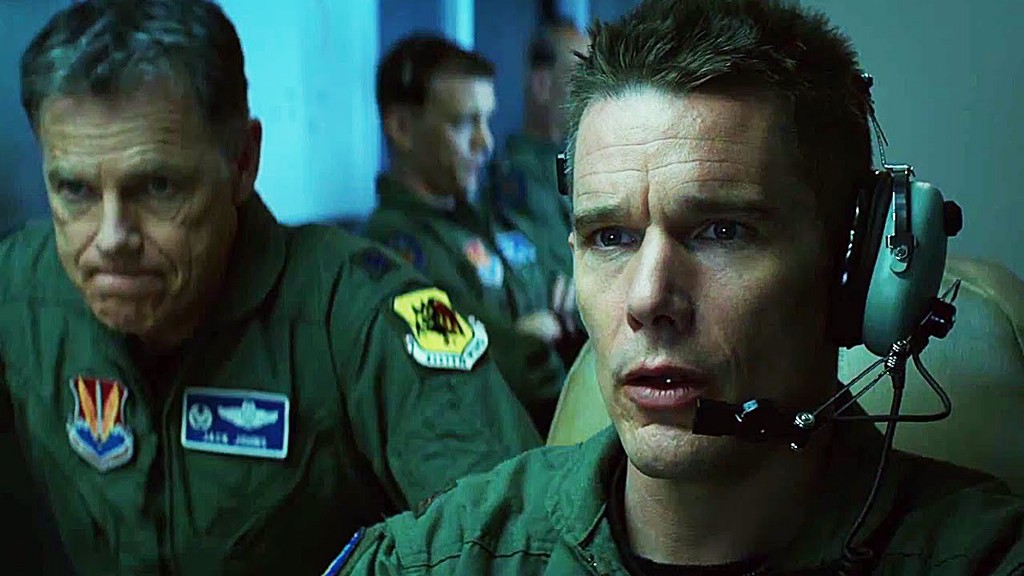

Good Kill, Easy War

by Emily Greenhouse

A drone strike comes fast, but the prelude is long: it stalks, it looms. Last fall, Steve Coll reported from Pakistan on the terror that civilians face as drones circle above them, sometimes for days. “People below looked up to watch the machines,” he wrote, “hovering at about twenty thousand feet, capable of unleashing fire at any moment, like dragon’s breath.” Good Kill, a new film by the writer and director Andrew Niccol, focusses on the people on the other end: the watchers, who bathe in the grimy imagery of the screen, always poised to deliver death from on high.

Ethan Hawke plays Tommy Egan, a U.S. Air Force Major who, after three thousand hours as the pilot of an F-16, is back stateside in Nevada, which means he can leave the base in Las Vegas every night to return home and spend time with the wife and kids. But this job, this life, isn’t what he signed up for. The film is a story, not subtly told, of stark moral disconnection, of a man longing for the honor and blustery courage of a Hemingway hero. Egan sits with other pilots in a metal trailer, operating drones. We watch as he watches as his target comes into focus. “Splash,” Egan, the unerring pilot, says. Then comes the explosion: “Good kill.”

Niccol makes movies about the intersection between technology and ethics — stories, as Hawke put it to me, “where technology pushes to a place where we’re on unsure ground ethically.” They do not tend toward understatement. But what they might lack in finesse, they can make up for in prescience and concern. The Truman Show, which he wrote and co-produced, presaged both the rise of reality TV and the near-ceaseless documentation and performance of our lives with tiny cameras that follow us everywhere, while Gattaca, the first project Niccol and Hawke worked on together, was released in 1997, and its vision of a future society carved by eugenics only feels more eerily prophetic as time goes on.

Good Kill, however, isn’t science fiction or a what-if. It’s a war movie that takes place, roughly speaking, in the present, during the escalation of the American drone war, and it asks a moral question of war waged by joystick: How much integrity is there to combat, as Hawke put it, “if you’re killing people but you’re not actually putting your own life at risk?” His unhappy character’s concern seems to be, at times, what becomes of the American hero of the battlefield when there is no battle, just a field of pixels? For Egan, Hawke said, “It’s not really about the war being good or bad, it’s about his own integrity. He’s feeling like a coward. This is a guy who I think dreamed of being a pilot. He’s grieving the death of his dream.”

Good Kill seems to be Niccol’s attempt to report out the answers to some of these questions. Hawke told me that when Niccol sent him the Good Kill script, “I realized how little I understood about the drone program. I didn’t have the criteria, the information, to have an educated opinion.” Niccol deliberately set the film in 2010 because it’s the last year that details of the drone program were open to journalists. “A lot of the words in the movie are not mine,” Niccol told the Hollywood Reporter. “They’re directly from the head of the CIA.” So the drama of Good Kill, according to Hawke, is simply our reality. “Technology makes the messy work of life easier to avoid,” he told me. “My generation is the first generation that’s been really asked to do this” — wage war by day, do dishes, watch Hulu, drink beer and play with dogs by night and by weekend. “I’ve met a few drone pilots, guys who work a whole shift flying a drone remotely with a joystick, who go home, buy potato chips and play video games all night long.”

Hawke seemed matter-of-fact in his approach to drones — he declined to comment on the specifics of President Obama’s drone program. As he put it to me, “Being against drones is kind of like being against the Internet — it’s the future.” He told me that he appreciated that Niccol’s thinking “doesn’t come from a left-wing or right-wing point of view, but a humanitarian point of view,” and that he is “always very suspect of art that claims to have a political agenda. I think if you just try to tell the truth from a character-based point of view, that truth will be political. I’ve never had an agenda with the audience about how people think. I’m kind of allergic to films that try to get your vote.”

Good Kill may not be quite partisan, but it is decidedly didactic. Niccol’s sensitivity and moral charge are clear, and the torment in Hawke’s performance is the most affecting and nuanced thing about Good Kill. But the other characters in the pilot’s hut feel like expository stand-ins. Nowhere is this more evident than in the onscreen depiction of women. It’s no surprise when the sole woman in Egan’s unit, Vera (Zoë Kravitz), gets the sexy outfits and the moral outrage (“Since when did we become Hamas… they give Nobel Peace Prizes for this now?’), plus some other contrived lines. Egan’s wife, Molly (January Jones), a former dancer, gets the usual alone together lines, as Egan, depressed, tunes out and hits the bottle. When a sullen Molly tells her husband, “to cheat on someone you have to be in a relationship,” she may as well be talking to Don Draper.

Even if indelicate, Good Kill comes at a moment, after Zero Dark Thirty and American Sniper, when American entertainment is looking at wars that resemble Call of Duty, not night-time raids. This past season on Homeland, we watched Carrie Mathison with her eyes on the drone feed. We saw her asset — her lover, even her ally — look up, and realize what will come. Frank Underwood on the latest season of House of Cards reckoned with the legal and moral matter of drone strikes — and of how much to tell the American public. And next Sunday at the Public Theater, Anne Hathaway will close her performance as a drone pilot, in “Grounded,” by George Brant. Some of her lines there mirror Egan’s: “I will see my daughter grow up. I will kiss my husband good night every night.” And, “the threat of death has been removed.” She takes her daughter to the mall and can’t escape the eye of the surveillance camera. “There’s always a camera, right? J. C. Penney or Afghanistan. Everything is witnessed.”

Hawke, in advance of the publicity rounds, clearly meditated on violence. Philosophizing a little on drones, Hawke mentioned Ayn Rand. He mentioned Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. He said, “The only two things that ever stopped wars is body bags coming home — the expense of the thing — or conquering a nation.” Today is a different time. “Here the cost is relatively cheap, but you’re never going to conquer, you’re not even there. It creates a state of perpetual war.” That seems to be the story Hawke wanted to tell. “War and cinema have had a long history and the only way the public have a real knowledge is through storytelling,” he said.

Good Kill, as a final product, is a maybe little too obvious. But when we’re dealing with something as murky, as obscured, as the American “War on Terror,” maybe obvious is what’s called for.