All My Cats Are Dead

by Mikki Halpin

My cat died last month. He had a good life — fifteen long, treat and cuddle-filled years during which he loved parties, burly men, sleeping with his head on mine, eating cardboard — and a good death.

Scientists who study such things say that we should all aim for “compression of mortality” — a long and healthy life, and then you die real fast. You don’t linger, you don’t make any tough decisions; you just live and then you die. My cat did compression of mortality like a champ. He started acting odd, was quickly diagnosed with a serious brain tumor, and went a couple of days later.

It’s hasn’t been that hard to accept that he’s being dead; it’s been hard to accept living without him. I’ve been crying a lot. For the first time in more than twenty years, I don’t have a cat. There is no one excited to see me when I get home, there is no one who will watch BBC period pieces TV with me and think they are having the best time ever, and there is no one whose delight in a piece of string can take my mind off of things. (I’m single!)

Of course, everyone keeps telling me to get a new cat. Or just assumes I will. But no fucking way. No fucking way am I getting another lovable, adorable, cuddly, affectionate, loyal little creature who is in fact a ticking time bomb set to explode my heart into a thousand pieces at some unknown point in the future. (I’m single.)

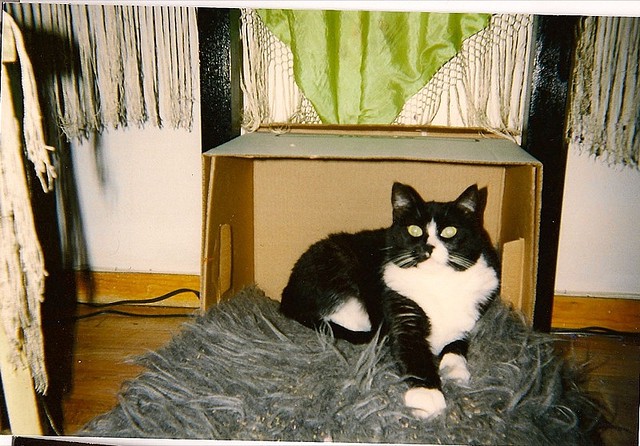

My first cat, Monster, was unplanned. I was going through a breakup — in the nineties, I was always going through a breakup — and had scuttled out of my apartment for errands before going back inside to lie on the couch, watch the OJ Simpson trial, and mull over whether life was worth living. At the hardware store on Santa Monica Boulevard, they had just found a little teeny black and white kitten, who had been pretty horribly abused. She had cuts and what seemed to be burns. She looked like the world had let her down and no one could be trusted; she looked like how I felt. I left my groceries at the hardware store and took her home.

The kitten, who turned out to be a year or two old — she was just tiny for her age — immediately went under the bed. She stayed there for about six months, with the only proof of life being a pair of glowing green eyes staring back whenever I put my head down to check on her or to introduce her to someone. My friend Ron asked if I was sure she wasn’t an owl. I got her out to go to the vet and get a clean bill of health, but otherwise my main contact with Monster was when I lay in bed at night, motionless, until she thought I was asleep: I’d listen to her scurry out to eat her food and use the litterbox before scurrying back under the bed as quickly as possible.

One night, as I was lying there, I felt a little beat of warm breath on the right side of my neck, and a faint purr. She had snuggled her tiny self on my shoulder, trusting and trembling at the same time. I held my breath and didn’t move, and she lasted about two minutes before diving back to her hideaway. (This, of course, is why I named her Monster — what else lives under the bed?)

After that, things progressed slowly, but steadily. Monster’s confidence was measured in inches. First she was ok being on the bed, at night, with me in it. Then she progressed to being on the bed during the day, under the covers, with me in the next room. Eventually we got to the point where I had to get a bigger desk chair to accommodate her on my lap as I worked. She remained terrified of other people — especially men — but gradually grew to rub against their legs and play fetch.

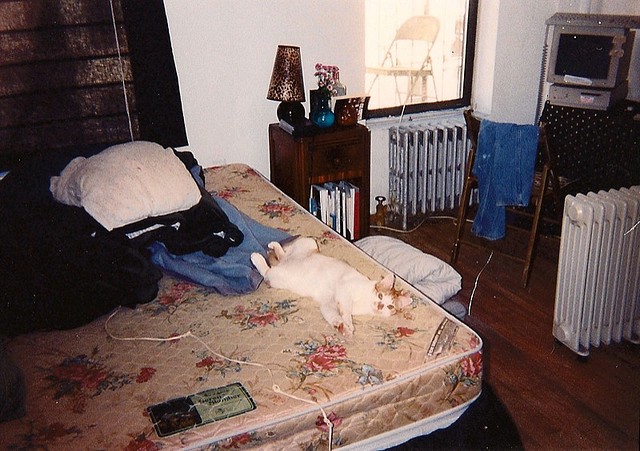

Once, I went to NYC for a week, and while I was gone she had gained several pounds. The vet explained that cats who are afraid of abandonment often overeat in fear that their food supply would dry up. We moved to NY, and settled into a little apartment near Gramercy where we spent the first few nights sleeping on a blanket on the floor. After my stuff arrived, my job started, and for the first time, Monster was home by herself all day, and sometimes at night, because I was going out.I hadn’t really thought about how this might affect her. She became incredibly needy whenever I got home, leaping into my arms, and often forcing me to carry her around like a baby while I cooked dinner or attended to other things. Neighbors who could see into my kitchen through the airshaft reported that she often sat on the windowsill and stared at them mournfully all day.

“She needs a friend,” the vet told me, going so far as to pull out a prescription pad and write “friend” on it, to make it more scientific. I was dubious. Two cats seemed like a lot for one woman in a fairly small apartment. What would potential dates say? Plus, twice as much litter? Twice as much food? What if Monster didn’t like the new cat? What if I didn’t?

A little while later, the vet called, saying he had found two kittens on the way to work, and that I should come in and meet them. They were both orange and white. One was cute, slightly neurotic and shy (a girl) and the other was a not overtly bright but very outgoing (a boy). My heart went out to the girl, but the boy seemed like what Monster and I needed.

Monster and Barrycat (named for his deep bass purr, odd when coming out of a four-pound kitten) fell in love immediately. She raised him and taught him manners, grooming, and all the ways of cats. Barrycat was everything Monster and I were not — carefree, goofy, freely affectionate, and kind of a slut. They slept with their arms around each other and their faces touching and it was beautiful.

One day, when Barrycat was two, I came back from a hike day and found him in a corner, unresponsive. The animal hospital said that he had acute thrombocytopenia, which means that he wasn’t making enough platelets. In cats, the disease is incredibly hard to spot; the damn little stoics will hold on until they get so sick there isn’t much to do. Barrycat died on the operating table when his organs shut down, and the hospital made the mistake of letting me in the room to be with him in his last moments. I ended up covered in his blood, and spent hours in the room they set up for us, morning his stiff little body, wrapped in a towel. I could only kiss his head.

I decided then, no more cats for me. It was the most traumatic thing I had ever been through, more visceral that the death of friends and other tragedies. I was wholly responsible for his little life, and I had not properly taken on that responsibility. Most people didn’t notice what was going on — 9/11 had just happened, I had just gone through another breakup, and I was just trying to carry on — though one a coworker kindly said in the elevator, “I know you are upset, but I haven’t seen you eat in a week.”

Monster suffered even more than I did. She walked around the apartment, looking for Barrycat, crying. She began licking her fur off. She stared at the neighbors again. Dr. Skip gave me the same advice: Get another friend. He even went so far as to suggest getting one who looked like Barrycat, which truly seemed like bullshit.

I went to a few shelters, but just the sight of the cats, and the thought of giving my heart to one made me feel sick. Monster went on Prozac. It helped — she seemed much less distraught, and some of her fur kept growing back. But I couldn’t help thinking about what the vet says. If what she needed was love, shouldn’t I give that to her?

I kept going to various shelters. For the most part I would walk in, then walk back out, crying. My goal in life is to avoid pain, and this seemed to be walking right into it. The fact that this was really for Monster was my way out. I wasn’t getting a new cat — she was.

At the PetSmart in Union Square, I saw a big orange and white kitty who had a bunch of kittens in the cage. The cat was grooming some of the kittens and letting the rest sleep on what looked to be a very comfortable, expansive, soft white belly. I looked closer at the sign on the cage and learned it was a boy named Pepito. I liked the way he was taking care of the kittens. It seemed to be what we needed. “Oh we always put the kittens in with Pepito!” said the volunteer. “He loves them and takes care of them.” Sorry, kittens. I took Pepito home.

I named him Fritz, because he was obviously German, and because meeting him had reminded me of the scene in Little Women where Jo spots Fritz Baer through the keyhole, playing with his nephews. His last name was Newman, because he was … our new man. (Monster’s last name was Halpin. We were a blended family.)

Monster and Fritz were never as close as Barrycat and Monster, because who could be, but they were lifelong buddies, grooming each other and cuddling all day when I was at work. They went through several severe illnesses with me, and a couple of surgeries, where it seemed like I would never get up off my couch and that was fine with them.

Two years ago, round Christmas, Monster got very sick. The vets told me to prepare to say goodbye, and I couldn’t. I could. Not. At that point, she was the longest relationship of my adult life. I had lived with her for more than half of it. I had lived with her longer than I lived with my parents. We had crisscrossed the country twice. We had been through a lot of boyfriends. I rocked her back and forth every night whispering, “Please don’t die. Please don’t die. I’m not ready. I’m not ready.”

She pulled through, much to the surprise of everyone except me. I knew she wouldn’t go until I could handle it. So I set out to treasure the time I had left with her. I worked at home as much as possible. I was already depressed, and reclusive, so I hardly went out, which cost me some friendships but thrilled her to no end. Fritz was her best buddy but I was still the number one light of her universe. I had a bad accident and shattered my ankle, which meant I spent another few months flat on my back on the couch. The cats both took advantage of the human-sized heating pad and the glasses of water I conveniently left around for them to drink out of.

By now, Monster was nineteen. I was on a trip to DC when my cat sitter called to say that she was acting a little strange — hiding, not talking, and not eating. I took the train home immediately, filled with dread but also with a bizarre sense of peace. I was prepared. We went to the hospital, and they said it was her time. I won’t say I wasn’t shaking and crying — I won’t say I’m not crying right now — but I was ready. I held her in my arms, and she put her nose in my neck, just like she did that first night, and she was gone. My heart, and my partner.

Somehow, I was able to get through work. I think it weirded people out. At work, I could pretend she was still at home, mostly. At home, I tried to fathom how Fritz must have been feeling. For most of his life, he had spent twenty-four hours a day with his best friend. Now he was stuck with me and I mostly cried and told him I was sorry.

People kept asking when I was going to get Fritz a friend, but this time I was determined to end the cycle: I would find him another home before another potential heartbreak entered my house. But Fritz seemed to love being an only cat. He was getting on in age, and had never gotten to be the center of attention. Now, if he got the prime seat on my lap while I was reading, he didn’t have to deal with Monster worming her way in to join him. We moved to a much smaller apartment, where a second cat would have been a pretty big inconvenience anyway.

Last month, like I said, Fritz had to leave. He snuggled like a pro until the very end. I couldn’t make it to his cremation, but the cemetery let me send all the amulets and treats that I wanted him to take with him to the afterlife, and promised to tell him that I loved him. His ashes are up on my little altar, next to Monster’s and Barrycat’s

People are already asking when or if I am getting a new cat, and I admit that I have an occasional twinge of loneliness that seems to be particularly cat-shaped. Then time telescopes and I see the inevitable end, another little jar of ashes. Sometimes I joke that if I could find a cat guaranteed to die after I do, I would consider adopting again.

There are upsides, honestly. No more litter. No more cat hair on my clothes. No more cat hair on my friends’ clothes. No more getting sitters when I travel, or rushing home to feed someone. No more chewed-up tulips. And I feel safe now. The unconditional love of a pet is a joy and a weight. They teach us that we can make another being happy just by being ourselves, and that sometimes, for no good reason, love and happiness end. I can take that lesson, and Monster’s, Barrycat’s, and Fritz’s love with me, but I can’t take on another cat.

New York City, June 17, 2015

★ Cool air brushed against the scalp. “It’s delightful outside, isn’t it?” a woman said. It was — utterly delightful, rich with promise. Sun on green leaves showed through the dense security mesh over the windows on the elementary school window. A man stooped and gathered little shiny bits of copper by the curb outside. The perfection invited plan-making: the Philharmonic in the Park, why not? But those ambitions from the brightness of midday met a late sky full of clouds. The sound of a passing plane rebounded off the low ceiling. Horse droppings lay in the splash marks of their attendant juices in the entry to the park. Balloons lunged and leaned against the barriers separating the general public from the VIP section. A raindrop or two fell. The balloons were liberated into the darkening sky, which got darker still as the introductory remarks and thanks to benefactors dragged on. Real rain began pattering down. Umbrellas and tarps came out, and a smell of wet grass and wet people thickened and clung to everything. The conductor apologized and vamped for a while as the string players struggled to protect their instruments from the oncoming elements. The three-year-old had brought his swim trunks and wanted to change into them. The stage and the program were hastily rearranged — Copland dismissed, the strings pushed further back from the stage. The rain subsided and the music returned. Eggplant colors appeared in the clouds around the edges of the park, while overhead appeared little curds of white, then deep blues and a glimpse of stars or planets.

Chopped Salad Joints, Ranked

6. Hale & Hearty

5. Just Salad

4. Dig Inn

3. Your local bodega that is trying to upscale in order to survive the crushing wave of rent hikes

2. Sweetgreen

1. Chop’t

Other deep thoughts on chopped salads are available here and here.

Photo by Larry Hoffman

The Members-Only Penthouse for Millennials

by Brendan O’Connor

On Wednesday night, around a hundred or so good-looking and successful twentysomethings (“Millennials”) gathered at a penthouse twenty stories above the Lower East Side. The majority of them were members of something called Magnises, a kind of social club for the aspiring entrepreneurial class. Magnises was founded two years ago by the broad-shouldered and affable Billy McFarland and the equally broad-shouldered but quieter Martin Howell. Until last month, Magnises operated out of a townhouse in the West Village; two weeks ago, they moved to the Hotel on Rivington, the penthouse of which was already being used as an event space.

“Our sunset cocktail hours have obviously been a huge hit, because — well, for obvious reasons,” Howell said, nodding to the view of Manhattan as we stood on the penthouse balcony. “People like to come down here, enjoy the sunset, enjoy the air of exclusivity. People love to bring their friends along too, because they know, without me, you wouldn’t have access to this. You know what I mean? It’s the kind of thing, we allow members to bring guests and then that makes the member feel all the better — in a Soho House way.”

“It’s been sort of interesting for us, as influencers,” Howell told me. “A lot of the members haven’t really been exposed to the Lower East Side at all, or in a very limited way,” he continued, “so the feedback’s been great: ‘Wow, we had no idea that the Lower East Side was, like, up and coming.’ Which is also why it’s great for us to work with local partners, with local small bars and stuff where we’re having one-off events, trying to bring the whole area up with us.”

�� #nyc #newdigs #LES #hotelrivington #magnises #penthouse #spoilednyc �

A photo posted by spoiled nyc (@spoiled_nyc) on Jun 17, 2015 at 8:25pm PDT

Both Howell and McFarland went to prep schools in New Jersey: Howell, who is from Zurich, to the prestigious Lawrenceville School — when I told him that I went to a nearby, less prestigious boarding school, he grimaced, and then we laughed — and then on to the University of Virginia; McFarland, who is from Short Hills, to the Pingry School, and then on to Bucknell, although he famously dropped out after a year.

According to Streeteasy, the lot at 107 Rivington Street was sold in 1998 for just under a million dollars, at sixteen dollars per square foot. Then, in 2000, it was sold for 3.8 million dollars, at sixty-three dollars per square foot. At the time, according to the website of Eastern Consolidated, a real estate investment service who represented both the buyer and the seller in the deal, there was a two-story building on the lot with over nine thousand cubic feet of air rights. Now, there is the glittering, twenty-story Hotel on Rivington. At 139 Ludlow Street, no more than a block away, the venerable Soho House is renovating a historic funeral home, where it will open its second location.

The original idea behind Magnises had been to provide twentysomethings with a more accessible (but still exclusive!) version of the invite-only American Express Centurion card — the so-called “black card” — that carries a five-thousand-dollar initiation fee, twenty-five hundred dollars in annual dues, and a reported quarter-million-dollar annual spending limit. “I was at dinner at La Esquina with friends, and we were all talking about how much we wanted a black card,” McFarland told the New York Times in December 2013. “So, that night, I did a ton of research on how to add a magnetic strip to a metal card without demagnetizing it and ruining data,” he said. “I got ahold of a place in China that could embed the magnetic strip onto the metal, and I had one made.”

Most coverage of Magnises thus far has focussed on this: that it is “the hot new way to spend money among NYC’s young elite,” as the New York Post described it last August. The Magnises card — which is, of course, black — is not actually itself a charge card, but can be used, for two hundred and fifty dollars per year, following an application process heavily reliant on referrals, in place of one’s normal debit or credit card; it is, essentially, a clone of an already existing card. (Disclosure: I applied for a Magnises membership about a year and a half ago in order to write a story about the process, but didn’t get a call back after my first interview — how embarrassing.) “If you think about it, the bank that you have doesn’t really matter. You probably picked whatever was closest to your apartment, or your school, and never really changed,” McFarland suggested to me. “Why not make that brand represent who you are, more relevant to you?”

��� VIP ACCESS ✔️� #penthouse #magnises #imcoolerthanyou #vipaccess #turntupthursday @n4ncyb0twin

A video posted by Karina Mejia (@anirakdesigns) on Jun 11, 2015 at 4:53pm PDT

But McFarland went on to de-emphasize the importance of the card in what Magnises is looking to do. “The card is a lot of fun, and is probably the best marketing tool we ever could have had — because it’s a physical, tangible thing, because it reminds you of the brand — but the brand is about the community of people, and how we connect,” he said. “That’s the real value.” Later, Howell said, “It’s a business card that no one ever throws away.”

Like any good entrepreneur, McFarland’s ambition is to weave a “fabric” that clings to every aspect of people’s lives — or at least the lives of Magnises members. “The key,” he said, “is that we’re with them everywhere they go.” Late last year, he told me, the company closed a round of nearly three million dollars in funding; in the next twelve months, Magnises plans to open up spaces for its members to use in ten new cities — they’ve already launched in Washington, D.C., while Boston and Chicago will follow, in July — and release an app. “We have the Magnises card, so we’re constantly in their wallet; we’re on their phone, through the Magnises app; and then we’re in their city, with a physical space,” he said.

“When we first launched the card, we noticed that whoever had the card, they wanted to sort of identify with each other — they considered themselves cool or whatever it was, they wanted to bond with each other, but there was no community,” Howell said. “We needed to create a space for them to all increase their networking potential.” That was when Magnises decided to start renting out a townhouse in the West Village. “This was not the plan on Day One,” he added.

Soon enough, Magnises outgrew the townhouse — the organization currently boasts nearly seven thousand members. (Most of those are in New York, McFarland said; there are around five hundred in D.C.) Magnises has access to the penthouse at the Hotel on Rivington from 12 P.M. to 9 P.M. almost every day: In the afternoons, it functions as a kind of co-working space; at night, it’s used for events and networking. “We have people that come in, they’re in the Lower East Side, they want to use the Wi-Fi, shoot a couple emails. We have people that come and have full-on meetings, that come do interviews. We have people that come to impress clients. We have people that are just coming because they’re new to New York — we have a lot of internationals that are new to New York and want to meet new friends,” Howell said. “So we have sort of the full mix, which is also what makes it so exciting. We’re not just a business networking organization, and we’re not just a social club. We cover the full spectrum.”

McFardland was reluctant to disclose how much Magnises is paying in rent for the sprawling penthouse, which, including the balcony, comprises three floors. “It’s hefty,” he said. “More than we were paying before,” for the townhouse at 22 Greenwich Avenue, which was listed at nearly fourteen thousand dollars per month when it last rented in January 2014. “It’s tens of thousands a month. More than ten, less than fifty.”

Access to the penthouse is not exclusive to the Magnises, however: The hotel can still use it to host events for other clients. According to nytix.com’s guide to New York City hotels that host bachelor parties — apparently there are not that many! — the average nightly rate for the penthouse is seventy-five hundred dollars. When that happens — or when a member wants to use the space for a private events like “birthdays, private brand launches” — Magnises members are offered a special corner of the restaurant on the ground floor of the hotel, as well as access to a large, private dining room. “It’s a better situation than it was before. In the old space, when there were private events, we had to turn people away at the door, whereas now we just redirect them to another space,” Howell said. “That’s a big step up. We don’t have any off days.”

To pay that “hefty” rent, in addition to its annual membership fees, Magnises also pursues partnerships with brands who seek access to the kind of young people who would pay two hundred and fifty dollars a year to be a part of something like, well, Magnises. “So, Tesla will pay us to do a car-racing experience with all of our members. Samsung will pay us to have their engineers come and talk to us about the new Galaxy phone to all of our iPhone users,” McFarland said. “Our concept is, you can advertise to people on our web platform and our physical space — through these events and experiences. There’s all these touch points for brands to advertise.”

Rather than seeking those partnerships out, Magnises is able to generate them from within, using its membership’s connections. “Almost every partnership comes from a member,” McFarland said. “Whether a member works there or has a friend who works there, almost every event or partnership we make is from an inbound member saying, hey, we really gotta do this, I work at XYZ, let’s do it.”

“We’ve created this platform where members feel truly comfortable bringing their own ideas and contributing in their own ways, and encouraging them to do so,” Howell said. “It’s been working beautifully, as members come back every day and try to contribute more to the community.” The DJ playing music at the party on Wednesday was a Magnises member, as is the rapper Wale, who performed at the recent D.C. launch party. (“The team behind Magnises are some real Zuckerberg types. They know what’s up and they know how to make stuff happen,” Wale told Billboard. “Once I met them I knew they would be blowing up, so that’s why I got involved.”) Reportedly, French Montana is also a Magnises member.

Magnises members who facilitate these kinds of deals, however, do not receive any part of the revenue generated as a result — there is no commission, or finder’s fee. “The cool factor is enough for them,” Howell said. One member, Greg Willyboro, who works in fashion, told me that of all the social clubs he belongs to — Ivy, Select, and one for French business people in America — Magnises is his favorite. “The people feel familiar,” he said. “We’re all entrepreneurial.”

Have you noticed a real estate listing that you would like to have investigated? Send cool tips, fun listings, and hot gossip to brendan@theawl.com.

Richard Sherman and 3 Unsung American Heroes Show You How Any Dream Can Become a Reality

by Awl Sponsors

Brought to you Oberto Beef Jerky.

This summer, Oberto is celebrating amazing triumphs of the human spirit with a brand new campaign entitled “Heroes of Summer.” Watch as Oberto Beef Jerky chronicles the drive and achievements of four individuals as they defy the odds and prove that with the power of belief, effort and hard work, anything is possible.

Meet the Heroes of Summer: NFL Star Richard Sherman, Blind Marathoner/Mountain Climber Randy Pierce, Dancer & Boston Marathon Survivor Adrianne Haslet-Davis, and leukemia-stricken youngster Brady Wein.

Be a part of the story!

Share your own story of personal triumph or inspiration for a chance to win a Toyota 4-Runner at www.Heroes.Oberto.com. For more information on Oberto, visit Oberto.com, Oberto on Facebook and Oberto on YouTube.

A Poem by Sandra Simonds

by Mark Bibbins, Editor

The Woman with the Foreign Accent

When I ask her where

she is originally from

she says, “Vermont.”

“Vermont?” I ask.

“Yes, Vermont,” she says folding each

dinner napkin into a swan and letting

each one slip from her hands as if

letting slip vowels or consonants

freeing them from a conquered language,

loosening them like feathers

from the borders, county lines,

dotted shapes of the interstate, removed

(as it were), from the ambulance

of the minor tongue, which,

in its opulence, must needlessly

justify itself over and over.

I think of my mother who says

to any passerby very proudly,

“I’m from France,” and I ask my friend

why the woman with the foreign accent

lies about her accent since my mother never lies

about being French

and my friend says, flatly,

“Because France is cool.”

What if the woman

with the foreign accent

is a Nazi and has spent

her whole life keeping her

family’s dark secret?

Or what if her father

is a monster and she decided

early on that she would

leave her mother tongue, move

to America, spend summers

on a motorcycle driving through

New England, stopping, on

the way to Vermont or Maine

at the occasional bed and breakfast

but also deciding to never, ever

get too emotionally close

to anyone she meets?

Everywhere in the hinterlands,

the countryside quakes

with regret or astonishment. The trains

and cows, the only remnants of collusion.

And when you really think about it,

everyone, everywhere

has an accent

when they go

somewhere else.

Everyone, that is, except babies.

Vermont? But, Vermont what?

Or what if the woman with the foreign accent

is a double agent? Or do double

agents even have

foreign accents? Or diplomats?

What if she’s the woman

who gave the “okay”

for the president of Poland’s plane

to be shot down? What if she’s the one

who pushed the red button

that sent an alarm so that

everyone at the factory

where they make toy trains

was suddenly instructed to leave

due to the chemical spill?

Is this how the community is spared?

Is this how the circles

of friendship tighten

into merry-go-rounds of gossip,

channels and pools of vague paranoia?

It was late in the evening and my

friends and I sat on the porch steps

drinking root beer and eating

crackers while the plump deer

of the environs chewed

blackberries. The sea,

in the background, did whatever

it does, suspiciously.

Beyond some

fence, another fence, and beyond

that fence, another fence, and perhaps

a bit farther out, something out

of nowhere lands on a house

and the explosion ripples outward

from the house to the watery village.

“Who, in the end,

stole the ping pong equipment?”

I asked my friends between crackers

but everyone shrugged

and, as a shorthand to all needlessly

tangled plots, the mystery is never solved

and word never does come back to us

from the village, except for the word

“carnage,” which the woman

with the foreign accent pronounces

“car-nich” but difficult to pay

attention to, considering tube tops

and violet leggings are back

in style and never mind

the complex drop off

pick up schedule of my children.

Let the gentle pastel rains

of Florida enable ways for us to feel

more deeply about homes, bodies,

and set them against the whorish intrigue

of book burning, the beloved

hashtags that bring us right to

the pinpoint morgue of the sun.

One must have a mind

of something. Not winter, exactly,

but something.

I began to question

why the woman with the accent

suddenly bloomed like minnows

enclosed in a globe of water, the habitat

which one could buy on the internet,

complete, a perfected love

insulated from the world around it,

devoid of class structure, of any structure

at all, in fact, taken out

of the small cardboard box

and placed on the bamboo

countertop of a sushi bar

in Seattle so the customers

don’t notice the minnows

immediately, but rather they see

an indistinct globe of water, with nothing

inside it except a bit of swaying

miniature seaweed, until midway

through dinner when, half drunk on sake

and full of salmon and rice — but this is when

it all comes to me —

I even put down my phone

for a second, savoring

the epiphany. I just know.

When the deer charged at me, I stepped out

of the way like a professional

and it ran straight

into the saltwater night.

I said goodbye to my friends

on the porch, went into the house,

walked over piles of library books,

my psyche encrusted

with wild lamentation, ridiculous

emotional excess,

obscene sentimentality.

The ping pong equipment,

neat in its white, netted bag,

sat on the kitchen table, next to

a ceramic vase of plastic flowers,

autumn colored the way a season

closes in on you, and then you look up

from the screen and it is already

gone and it felt as if, all along,

everyone was in on it,

as if the equipment

had never disappeared.

Sandra Simonds is the author of four books of poetry: Warsaw Bikini (Bloof Books, 2009), Mother Was a Tragic Girl (Cleveland State University, 2012), The Sonnets (Bloof Books, 2014) and Ventura Highway in the Sunshine (Saturnalia, 2015).

You will find more poems here. You may contact the editor at poems@theawl.com.

Three Moments in White and Black History in Charleston, South Carolina

No doubt the last thing that [Denmark] Vesey and his co-conspirators expected was that there would be whites in Charleston who supported their revolt…. At the time of the trial, the four men were all judged to have been between forty and fifty years of age…. in place of asking the men their actual ages, the court visually estimated and recorded them — a humiliating practice typically reserved for African American in legal proceedings, thereby conferring at the outset a kind of “less than white” status on the four….

The first white defendant, William Allen… “spoke of large parcels of arms secreted near the city….” Allen’s overtures had been reported by two free blacks… “The negroes objected that he (Allen) being a white man, could not be safely trusted by them. To this he replied, that ‘though he had a white face, he was a negro in heart.’”

John Igneshias, the second white defendant, was described as being “a Spaniard, a seafaring man….” As with the other white men on trial, the most damaging evidence against Igneshias were white witnesses, who testified that he had angrily declared to slaves in town after the plot’s discovery that “he disliked everything in Charleston, but the Negroes and the sailors.” According to testimony, Igneshias additionally exclaimed, “Damn them [the whites], I would kill them all.”

The third defendant… was overheard by a “respectable” white male witness… “speaking to several negroes concerning the execution of some of the slaves. ‘Poor creatures,’ said he, ‘my heart bleeds for you; the negroes executed were innocent… you… ought not to have permitted it… and you must rescue those who are still to be hanged.’”

The fourth defendant… allegedly came offering to lead two thousand men against the state, declaring that “the Negroes ought to fight for their liberty” and “that they had as much right to fight for their liberty as the white people….”

Not surprisingly… two of these reputed offers of aid… however well intentioned, were also paternalistic-sounding schemes to lead, not follow, large numbers of armed black people to freedom.

— Philip F. Rubio, “’Though he had a white face, he was a negro in heart’: Examining the white men convicted of supporting the 1822 Denmark Vesey slave insurrection conspiracy,” The South Carolina Historical Magazine, Vol. 113, No. 1 (January, 2012)

Slavery in Charleston ended when the 21st United Colored Troops, the 54th and 55th Massachusetts Volunteer Regiments, and the former slaves of the 3rd and 4th South Carolina Regiments entered Charleston in 1865. Charleston’s “black community… began taking charge of the new situation and assert themselves” as free people equal to whites. They “viewed themselves as a ‘working class of people’ seeking to benefit from ‘the fruits of their labor….’”

Nevertheless, slaves who were domestics redefined the rules of work and decided which white employer would employ them. Many left their former master/mistress for new employers as a means of creating personal autonomy. Blacks even fought off white plans to replace them with Asian and European immigrant labor. African Americans defined personal freedom by establishing bank and savings accounts for dependents in the Freedmen’s Bank…. African Americans understood that “freedom was a battle.” They gave no quarter in their attempts to maintain their new found freedom…. While African Americans defended themselves on Charleston’s streets from abusive white police officers, white Union soldiers, and whites who refused to recognize black freedom, Charleston’s African Americans could not protect themselves from the economic depressions…. They built their churches and paid educational tuition out of salaries constrained by local, national and global depressions.

— Gregory Mixon, “Reviewed Work: Seizing the New Day: African Americans in Post-Civil War Charleston by Wilbert L. Jenkins,” The Journal of Negro History Vol. 86, No. 1 (Winter, 2001).

In late winter 1867 the Congressional Reconstruction Acts imposed military rule on the South and required a non-racial franchise…. When a constitutional convention was held in the city during early 1868, over one-half of the delegates were black. This convention instituted universal male suffrage…. In May thirteen of eighteen aldermen were also removed and seven of their appointed replacements were black… All had been free before the war and represented a new class of leadership in Charleston’s black community. Throughout the period, except for the years 1871–1873, half the seats in the city council were occupied by black men….

The reaction of white Charleston to the prospect of black officials was swift and negative. They felt that the seeming social and political equalitarianism of Reconstruction degraded their once glorious city to the depths of a Paris gripped in the throes of the French Revolution. Chagrined at the unfolding scenes of Reconstruction, Eliza Holmes wrote a friend, “we are being made however, day by day, to realize, the… equalities of all things.” Aghast at the appointment of the black Dr. Benjamin Boseman as postmaster for the city, Holmes continued, “surely our humiliation has been great when a Black Postmaster is established here at Headquarters and our Gentlemens Son’s [sic] to work under his biddings — .” Bearing incredulous witness to the changes in the city council under military rule, Augustine Smith wrote in disgust, “we actually have negroes in Council. It is the hardest thing we have yet had done to us.”

— Bernard E. Powers, Jr., “Community Evolution and Race Relations in Reconstruction Charleston, South Carolina,” The South Carolina Historical Magazine, Vol. 95, No. 1 (Jan., 1994)

Bricks Back

“At the creative end, for architects, bricks are an incredibly open-ended material, allowing all sorts of interesting designs. Of course, most bricks go into housing, but they’re also becoming more sought-after for top-end design. They’re fashionable.”