Mikael Seifu, "Brass"

Lush and formless and yet not boring at all; thirteen minutes worth listening to a few times in a row.

Terrible International

Our country’s global moral and political influence may be on the decline, but it’s nice to know we still have the power to fuck things up pretty bad culturally if we want to.

New York City, June 23, 2015

★★★★★ The elevator on the way out into the day was already hot. High bright clouds switched the baking heat of the sun off and on. A police horse with white streaks in its mane and tail and rump ambled along the edge of the soccer camp. Mushrooms had sprouted in all the forks of one elm’s roots, while the next elm over stood mushroom-free. Downtown the morning light was chalky. By afternoon, the clouds were a thin sheet, making the roof a pleasant refuge from the air conditioning. A medium-gray cloud blanket was draped low down in the north, over the Empire State Building, but it didn’t amount to a threat. The real clouds came in over rush hour, and with them — a raindrop, or an air conditioner drip? A rumble of thunder, or a taxi revving? Then raindrops came for sure, and a gust and a flash, and certain thunder. But the B train outran or outmaneuvered the onslaught. The radar map on the phone showed something slashing through Brooklyn and away, but the people coming into the Columbus Circle station were still dry, the streets above still breezeless. One of the new New Beetles sat in a crosswalk with rain beaded on it, carried in from somewhere else. Finally a little rain fell, but only a little. Odd bright patches appeared in the west, even as a giant dark zeppelin-belly of cloud cruised by, flying uptown, gondola-shape dangling from it. A burning gold light found an opening in the clouds and came through strongly enough to cast a shadow on the wardrobe door on the far side of the room. Then came not just an intimation of the sun but the sun itself, framed above the next apartment in a gap maybe four times its width and twice its height. Out through the gap poured not only golds but restored blues and even whites. One long black spike of cloud still drifted in front of it, and after that passed, a little sprig of black followed. But the golden light was flooding everything, flocked with white and tinged purple. What had been the clear blue parts abruptly became textured, rippling gold too. Soft little olive clouds floated under the display, as the gold became orange, then red, then purple. Down low in New Jersey was a smooth milky purple, spreading like paint in paint thinner. The sky was blood, wine, tangerine peels, green glass. It was so far beyond the powers of a camera that the only thing to do was to shoot it in black and white.

Boomtown WTC

With development booming, and media companies like Condé Nast starting to populate the area’s skyscrapers, Lower Manhattan’s Neil Patrick Harris-like image turnaround seems to be in full swing. … “It’s beyond our wildest dreams,” said Peter Poulakakos, a restaurant entrepreneur who has invested in this swath of downtown since 1999. It has gone from sliding toward becoming a ghost town, he said, to “a neighborhood that competes with all the major developing cities in the world.”

Those big names will be showing up with their gold-prospecting gear only to find that early adopters like Danny Meyer, Andrew Carmellini and Stephen Starr have already set up camp. They built restaurants in anticipation of a growth spurt, and since Condé Nast started moving into 1 World Trade Center in November, they’ve been adjusting their menus and schedules to fit the eating habits of editors from Vogue and GQ. The Odeon has added a breakfast service. Graydon Carter of Vanity Fair, Dan Peres of Details, Pilar Guzmán of Condé Nast Traveler and Michael Hainey of GQ can be spotted there on a regular basis, commanding tables or phone-tapping privately at the bar.

It would perhaps be a mistake for the proprietors beginning to profit from the boomtown that has emerged in the shadow of the World Trade Center to think that people who currently comprise their new customer base — who seem to be drawn largely from the media, according to the media, anyway — will necessarily dominate the composition or tenor of the neighborhood in the coming years. Conde Nast has about thirty-five hundred employees occupying floors twenty through forty-four of One World Trade Center — out of seventy-eight floors designated for office use — and Time Inc. is bringing a little (or a lot?) less than three thousand employees to Brookfield Place later this fall, a fraction of the people who will be working (and living!) in the area.

Maybe think of the media companies and their employees as first-wave gentrifiers; a richer, more robust wave is just around the corner, and those people are far less likely to be permanently diminished or crushed out of existence if there’s a major dip in the ad market. Gotta think long term, you know?

Alessandra Stanley and the Diminishment of Criticism

exclusive look at TV Twitter finding out that Alessandra Stanley is no longer the NYT TV critic pic.twitter.com/f1xOAAFzFG

— Bertrand Hustle (@EricThurm) June 24, 2015

Over the years, I can think of no person that New York readers of the New York Times wanted replaced more than Alessandra Stanley — besides, of course, her friend Maureen Dowd. The difference is, they were wrong about Dowd.

Announced today, Stanley’s departure — she has held the post since, as near as the Internet can tell, January of 2003, although she wrote about TV in 2002 — is overdue. I suspect the Times kept her on this long just to look like they weren’t bowing to bloggers and those oh-so-important users of Twitter who like to discuss how much they hate her work. But Stanley’s recent work exhibits that she’s surely stayed on past multiple cycles of burnout. Her reviews of two very thoughtful and unusual new TV shows — Mr. Robot and Sense8 — were neither revelatory nor inaccurate but were more like flicks of some big cat’s lazy tail on a hot day. There are at this point hundreds of these place-filling stories in the archives of the paper. They are a far cry from her earlier work, like the 2003 review of Jimmy Kimmel’s show, which begins: “It would be unconscionable to judge ABC’s new late-night talk show, ‘Jimmy Kimmel Live!’ after one week. Two nights are plenty.” Now you will be lucky to get an inspired sentence or two.

But how could she do more? The practice of endless criticism is terrible! I would look at my TV in terror after just six months. But the times (lower-case) made it all much worse, because Stanley’s career as chief TV critic overlapped almost completely with the existence of Gawker. (If Gawker goes out of business next month, it’ll be the neatest narrative coincidence ever.) Stanley was the site’s perfect hometown enemy; perhaps she still is today. Stanley was elected — although it might be fair to say that she volunteered — as a symbol of a generation of aging, phoning-it-in journalists of power who suffered no public consequences for inaccuracy or badness, even while their good work went unremarked upon. These were people who thought the Internet was beneath them. Dowd, and Dowd and Stanley’s friend Michiko Kakutani, have also gotten a similar treatment — How dare this woman step all over the Clintons? and How dare this woman step all over this nice man’s book? — and there’s several good grad school theses about this and them and how they’re all women and etc. But then, do people treat Roberta Smith or Manohla Dargis like that? I don’t really think they do, although I can’t remember the last time I saw either of them pick up a big correction. What’s more, plenty of women have expressed vivid hatred of the work of Stanley anyway; certainly more than a few Times employees have openly expressed astonishment at the longevity of Stanley in this role.

The Alessandra Stanley announcement reads like when you take your boo’s phone and tweet nice things about yourself from their account.

— Jamilah Lemieux (@JamilahLemieux) June 24, 2015

Critics of the Times were never safe from criticism, to be sure. There was no better time, back in some misty day. “The nicest mail was from people who wrote as though they thought I was having a hard time,” Renata Adler wrote of reader input during her brief stint as the Times film critic. But being Gawker’s favorite punching bag must have been extra-tiresome.

Because, you know, what power did they have really? Just how far up were any of us punching? So Kakutani and Stanley work at a well-known newspaper. Big whoop. It didn’t turn out to be such a big deal. At this point, salaries, benefits and job security may very well be better at Gawker than they are for many at the Times. At the same time, over these dozen years, agents and writers alike have largely stopped reading the daily book reviews. Producers and publicists don’t read the TV and film reviews as they used to. Mega-dealer David Zwirner is not springing from his bed at dawn on Fridays to check the weekly art exhibition reviews. They do not make or break artists as they once did. These are not the days of Frank Rich closing down Broadway productions with 800 words of copy.

The paper’s criticism is valuable, but the critics — maybe the institution at large? — lack both the vitality and the influence that they (it?) enjoyed. I have always believed, rightly or wrongly, that the longevity of critics’ tenures is what is responsible for the dimming of the former. The paper, too, is afraid to inflame. The copy desk and the bench of editors, even as the paper changes and loosens, still will not tolerate crudeness, lewdness, and sternness. They do not often tolerate ferocity.

Stanley’s role as TV critic wasn’t really ever even a good match. The department kept her sharpest claws filed down. She could rarely be naturally rancorous in a fun way. She was ripe for misunderstanding. Her tone ruffled TV enthusiasts and industry people alike. Her new beat, covering the very rich, is at last, an impeccable match. It’ll be a treat for everyone. The more disastrous it might be, even, the better for all of us. This is the very definition of going big or going home. How great.

The thing is, I trust in Alessandra Stanley SO MUCH that I’m sure she’ll have us all feeling sorry for the 1% in a few months

— Ira Madison III (@irathethird) June 24, 2015

And it’s terrific to breathe a bit of air into the department of critics. Critics are long-serving, and they are uniform as hell. Other departments are also getting a slow and deliberate shake-up. It’s needed. But nothing will meet with as much celebration as the departure of Stanley. Except… who will we kick around now? Oh don’t be silly, we’ll find someone!

Breaches of Subway Etiquette, Ranked

by Brendan O’Connor

54. Gross kissing.

53. Talking on the phone on an above-ground train.

52. Talking on the phone on a subterranean train (how???).

51. Being a dick to the people handing out copies of the day’s AM New York or Metro New York.

50. Not moving so a pair of friends can sit together.

49. Not making way for people transferring across the platform from one train to another.

48. Not taking your backpack off and putting it between your feet when the train is crowded.

47. Not consolidating your groceries.

46. Rolling your eyes at someone with a stroller.

45. Not distributing evenly across the entire platform.

44. Not getting out of the Showtime Kids’ way.

43. Acknowledging the Showtime Kids in any way other than to get out of their way and maybe watch out of the corner of your eye and smile a little bit, unless they’re really good.

42. Bringing your bike on the train (non-rush hours)

41. Eating smelly food.

40. Eating messy food.

39. Eating food that looks good.

38. Bringing non-service animals onto the train during rush hour.

37. Making eye contact.

36. Singing.

35. Talking loudly.

34. Talking to your friend who is sitting on the other side of the car.

33. Talking to me.

32. Exiting through the turnstiles when there is a rush of people trying to make the train.

31. Exiting through the turnstiles after someone has already just swiped.

30. Failing to swipe your MTA card correctly more than three times; it’s not your fault, but you still need to get in the back of the line and start over.

29. Sticking your feet out into the middle of the subway car when sitting.

28. Not giving the kid selling snacks a dollar for a snack (unless he’s being extremely annoying about it).

27. Spilling a liquid on the seat and not cleaning it up.

26. Listening to music without headphones.

25. Listening to music with headphones, but super loudly.

24. Beatboxing.

23. Not offering a swipe, on your way out, if you have an unlimited monthly card, to people who are looking for a swipe.

22. Anything that would otherwise normally take place in a bathroom:

a. Picking nose.

b. Cleaning ears.

c. Clipping nails.

21. Bike on the train (rush hours)

20. Not moving to the center of the car when it’s crowded.

19. Leaving your garbage behind — except today’s newspaper.

18. Walking too slowly up the left side of the escalator.

17. Stopping on the left side of the escalator.

16. Stopping on the staircase to send an email or text message.

15. Stopping at the bottom of the stairs or escalator.

14. Stopping at the top of the stairs or escalator.

13. Stopping anywhere, for any reason, other than the platform.

12. Using your laptop on the train.

11. Manspreading.

10. Not moving in order to maximize the number of bodies that can fit on the bench.

9. Not leaning forward, to allow more people to sit back, if you are a wider person.

8. Getting frustrated with other people on the bench. You’re sitting — check your prviasjldfk.

7. Leaning against the middle pole with your whole body.

6. Not getting up for a pregnant lady, or an elderly person, or a person with a handicap, or a person who has sustained a debilitating injury.

5. Not helping someone with a stroller carry the stroller up or down the stairs.

4. Holding the door for someone who is oh-my-god-so-close-please-hold-the-door to making the train. Leave them, they’re on their own now. It’s not your responsibility to help them get to work on time.*

3. Not letting people get off the train first before getting on it.

2. Not getting out of the way of people getting off the train.

1. Drinking a drink from a can or bottle and letting the condensation drip onto someone who is seated.

* However, if they do get a foot or hand in the door, you should help them open it, because good effort.

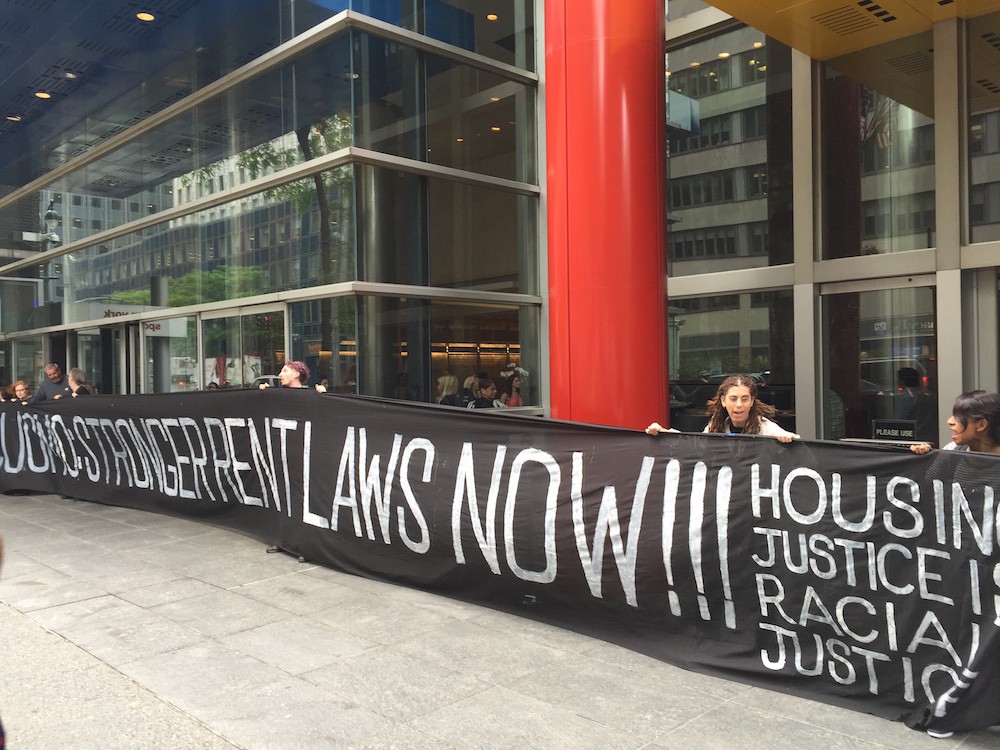

Can Successfully Kicked Down Road Past Rent-Controlled Apartments

The Assembly, controlled by Democrats, had pushed to strengthen rent regulations so that fewer apartments would become market rate in future years, but it faced opposition from the Republican-controlled Senate. As part of the agreement, the rent threshold at which a vacant apartment can be deregulated will increase to $2,700, from $2,500. That threshold would rise in the future based on increases in regulated rents approved by the Rent Guidelines Board. The Assembly speaker, Carl E. Heastie, a Bronx Democrat, said the agreement would “slow the loss of affordable housing in the city of New York.” Mr. Cuomo deemed the agreement “a major step forward in terms of tenant protection.”

The New York State Legislature asks, “Why bother fixing the current problems with rent control when you could make someone else do it in four years?”

The Flies in Kehinde Wiley's Milk

by Vinson Cunningham

Equestrian Portrait of King Philip II, perhaps the most famous work by the artist Kehinde Wiley, is a portrait of Michael Jackson that was commissioned not long before the megastar’s death and unveiled not long after. The painting is a beat-by-beat paraphrase of Rubens’ portrait of King Philip: Wiley’s MJ sits atop a whitish, curly-maned horse and wears black and gold armor, duly ornate, reminiscent of his trademark late-eighties betasslement. Cherubs fly overhead, offering a wreath. Some countryside unfolds toward the horizon.

King Philip is as representative a specimen as any of Wiley’s signature style, which is easy enough to grasp, and then to recognize again and again as it makes the pop-culture rounds, on Empire and beyond: He poses hyper-contemporary figures — mostly black, mostly male, clad mostly in sweatsuits and bubble jackets and Timberland boots — in brazen imitation of the old masters. His subjects are set against intricate patterns of flowers and tapestries, or, as in Philip, against skillful approximations of the landscapes and cloakrooms that background the old portraits from which Wiley draws inspiration.

Wiley’s first career survey, Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic, which went up at the Brooklyn Museum earlier this year, traced the evolution of this hybrid style, beginning with its prehistory; early efforts like Conspicuous Fraud Series #1 (Eminence), a sketch-like portrait of a businessman whose Afro has exploded into smoky tentacles, gave way to the bright, glossy numbers that have become Wiley’s stock-in-trade. Perhaps in answer to the increasingly loud — and somewhat fair — accusations of what a recent Village Voice review called a “deadening sameness” in Wiley’s work, there were hints, too, of a way forward: A series of bronze busts and stained glass windows pointed toward the potential for future applications of the artist’s core preoccupations, while a set of mini-portraits, after Memling, were the most uncluttered, intriguing items on display.

Accompanying many of the pieces were quick snippets of praise and analysis from curators, art-historians, and other Wiley-watchers. Largely, they echoed what has become at least half of the standard critical patter on the portraitist. Catherina Machada, the Seattle Art Museum’s contemporary art curator, says that the Ingres-inspired St. Anthony of Padua “prompts a conversation about portraiture as a vehicle for representations of power.” Morpheus, a flower-strewn reworking of Houdon’s sculpture, points, according to Yale’s Kobena Mercer, to “the potential for human identities to morph out of history and into new future possibilities.” Wiley’s own words also stick fairly closely to the script:

“[T]hat’s partly the success of my work — the ability to straddle both of those worlds, the ability to have a young black girl walk into the Brooklyn Museum and see paintings she recognizes not because of their art or historical influence but because of their inflection, in terms of colors, their specificity and presence.”

If reflection, recognition, representation — so often identified with Wiley’s work — comprised its entire attraction, I’d be grateful for its existence, in the same way that I’m grateful for the existence of, say, Tyler Perry. Mere existence is a real and valuable politics, one whose importance shouldn’t be underestimated. But this, for me, is where the difficulty starts with Wiley: If his paintings have any value as art qua art, that value lies in something else — his best paintings read as jokes.

A good joke is a kind of control, exerted backwards: The bit isn’t understood until the listener can see how punchline proceeds from premise, how premise, perhaps, proceeds from something small and hurt in the mind of the comic on the stage. There’s linearity, a narrative; despite its best efforts, visual art can’t really be said to narrate anything, not in the truest sense. But with Wiley’s work — maybe because it’s so surreal, so obviously from some plastic-coated alternate universe — you sense a kind of disoriented story structure. His funniest paintings almost ask for a caption.

The joke extends beyond any single portrait: This is where the other half of the rap on Wiley — that his oft-repeated style amounts to little more than a formula — comes in. His repetitiveness operates in a way not dissimilar from Chris Rock’s rhythmic punchlines — something like the chorus to a song, eventually revealing something that the Brooklyn Museum show bears out: Wiley has joined a long line of artists preoccupied with how being a black person among white people is not only difficult or isolating or a problem, but is also, more often than not, fucking hilarious.

Others have had their fun with the idea: In his semi-autobiographical summer-novel, Sag Harbor, Colson Whitehead has his young narrator remember bar mitzvah season:

I was used to being the only black kid in the room — I was only there because I had met these assorted Abes and Sarahs and Dannys in a Manhattan private school, after all — but there was something instructive about being the only black kid at a bar mitzvah. Every bar or bat mitzvah should have at least one black kid with a yarmulke hovering on his Afro — it’s a nice visual joke, let’s just get that out of the way, but more important it trains the kid in question to determine when people in the corner of his eye are talking about him and when they are not…

…“Who’s that?” “Whisper whisper a friend of Andy’s from school.” “So regal and composed — he looks like a young Sidney Poitier.” “Whisper whisper or the son of an African Diplomat!”

That yarmulke, the crucial half of Whitehead’s “visual joke,” is like MJ’s steed in “King Philip” (or perhaps like the brocaded outfit, or like the angels trailing overhead, or like the countryside behind, or even like the deadpan museum wall from which the frame hangs, enabling everything). It is a piece of otherwise unremarkable context, suddenly sharpened and used to lead us through the stations of comedy’s cross: interest, recognition, surprise, release, repeat.

Once your eye lifts its way past hooves and muscle, spurs and gloves, spread across the enormous canvas of King Philip, it alights on Michael’s face, so absurdly and somehow perfectly out of place. Then you laugh.

There’s something funny about Kanye West, let’s admit it. It’s not just his long history of ill-timed socio-political and pop-cultural commentary; not just items like that recent gif of him at the Bulls game, forcing his face down the swatch-scale from delight to diffidence. No, there’s something else, something more fundamental, born from his vast, naked, unquenchable desire to fit in. This seat-at-the-table fixation lurks behind many of his most emotional (and often perversely justifiable) fits of pique: He is miffed about never having won a Grammy against a white artist, even though he possesses more than twenty of the things, and, having sold uncountable pairs of Nikes — then auto-tuned a good-bye letter to the company, gone for Adidas — he stands pounding at the gates of whichever European fashion house will have him, even for an internship. Thus Kanye’s anguished response when, during an appearance on the radio show Sway in the Morning, the show’s eponymous host suggested that he go it alone, Fendis and Pradas be damned:

Sway: But why don’t you empower yourself…and do it yourself?

Kanye: How, Sway?

Sway: Take a few steps back, and —

Kanye: You ain’t got the answers man! You ain’t got the answers! You ain’t got the answers, Sway! I been doing this more than you! You ain’t got the answers! You ain’t been doing the education! You ain’t spend 13 million dollars of your own money trying to empower yourself!

West, like Wiley’s smirking figures, knows that the game is played within the borders of foreign frames.

It is in this way, through a loud and unashamed — and, yes, sometimes comic — insistence on his own belonging, dissonances be damned, that Kanye West remains America’s lone true rock star, if by “rock star” we mean the raw and awkward forerunner of what eventually becomes normal: His odd theme, so loudly pronounced, has cleared the way for infinite variation. His person and positioning, somewhat like his music, have given others the cover to create something startling and new, but also so organically arrived at that it’s already all but taken for granted: namely, the weird fact that, here in the mid-twenty-teens, the iconography of black musical production has completed a five-hundred-year life cycle, from field holler to Fader. The oft-cited borrowing, or theft, or sublimation, or whatever, of properties ranging from the twelve-bar blues to the sixteen-bar rap verse has finally, and somewhat miraculously, culminated in a pop landscape lorded over by black artists. Not just artists, either, but, in the popular imagination, auteurs. Musical Negroes have at long last joined prestige TV show-runners on the list of fortunates whose output is regarded with the kind of reverence and patient befuddlement once reserved for heavy books and quiet movies.

The music-critical media just months ago devoted itself, in an impressively sustained few moments of collective focus, to the long awaited return of the R&B; singer-songwriter D’Angelo, who hadn’t released an album since Hillary Clinton last occupied the White House. His light-headed, lyrically incomprehensible Black Messiah, released on what seemed like a whim in the wake of the troubles in Ferguson and beyond, was treated like a particularly important snippet of Talmud, combed and re-combed for whatever insights — music-theoretical or hyper-contemporary — it might offer.

A few months later, it was Kendrick Lamar’s turn to satisfy our current critical culture’s hunger for big, meaning-laden objects to devour, digest, and ultimately leave it its wake. Same abrupt, surprise-ish release date, same intensely attentive reading, plus a meta-conversation about the role of the generational savior in hip-hop mythology — a role which, for better or worse, Lamar appears lab-engineered to inhabit. But, as Jay Caspian Kang outlined in an incisive essay in the New York Times Magazine, Lamar’s To Pimp A Butterfly suffered somewhat under the weight of the designation, and, perhaps, of the suddenly awed tones of the (mostly white) writerly corps tasked with interpreting his effort. Taking up the tools of Western modernism — denseness, disjointedness, impenetrability — Kendrick largely left behind humor, a crucial tool passed down by the rap messiahs who came before him.

Which brings us back to Kanye West, through whom rage and isolation are almost always transubstantiated into hilarity. Consider a few lines from Kanye’s “New Slaves,” punctuating a verse heralded by, well, himself as the greatest rap verse “OF ALL TIME IN THE HISTORY OF RAP MUSIC, PERIOD”:

They prolly all in the Hamptons

Braggin’ ‘bout what they made

Fuck you and your Hampton house

I’ll fuck your Hampton spouse

Came on her Hampton blouse

And in her Hampton mouth

This bit of blues-descended overstatement would do well as a setting for Kehinde Wiley’s inevitable portrait of West: Imagine Kanye, skin asmolder in purples and blues, dressed in sightless garden-party white, behind him the slightly menacing striped trim of a Hamptons lawn. A shingled house somewhere in the distance, off-center. An UberCHOPPER hanging overhead. Kanye threatening to rip through the canvas and embarrass you in front of your guests.

There’s something to learn from the fact that Ralph Ellison, America’s great artist of racial encounter, also happens to be one of our funniest writers. He squeezed infinite amusement, sometimes brutal, from the optics of isolation: A man writing prologues from the black of a cave; little boys watched boxing for coins, on and on. In Juneteenth, the posthumously published section of his never-finished second novel, Ellison performs a deft reversal, then re-reversal, of the theme, tracing in Falkneresque stream-of-consciousness the life and trials of a white boy raised and trained to preach by a black tent revivalist, taught to think himself a Negro, only to become, later in life, a race-baiting U.S. Senator.

In his short essay A Special Message to Subscribers, Ellison describes the subconscious process that led to the creation of Invisible Man’s protagonist. A voice, he says, comes streaming into his ears while he sits at his desk in Vermont, the voice of a comedian in blackface, calling himself an “invisible man” from the famous Apollo stage.

Here’s Ellison:

He had described himself as “invisible” which…suggested a play on words inspired by a then popular sociological formulation which held that black Americans saw dark days because of their “high visibility.” Translated into the ironic mode of Negro American idiom this meant that God had done it all with his creative tar brush back when He had said, “Let there be light,” and that Negroes suffered discrimination and were penalized not because of their individual infractions of the rules which give order to American society, but because they, like flies in the milk, were just naturally more visible than white folk.

Yes: flies in the milk. In Kehinde Wiley’s painted world, the textiles and the landscapes are the milk, the hip-hop kids the swimming flies — not drowning, but cracking up.

Photos by Libby Rosof (1, 2)

Maybe You're Sad Because You Want To Be Sad (And Also Because You Suck)

“New research suggests that even when depressed people have the opportunity to decrease their sadness, they don’t necessarily try to do so.”