LaCroix Sparkling Water Flavors, Ranked

13. Peach-Pear

12. Lime

11. Lemon

10. Orange

9. Cran-Raspberry

8. Berry

7. Pure

6. Passionfruit

5. Coconut

4. Tangerine¹

3. Mango

2. Apricot

1. Pamplemousse

1. Ed note: this post was updated on April 6, 2016 to account for Tangerine’s auspicious debut.

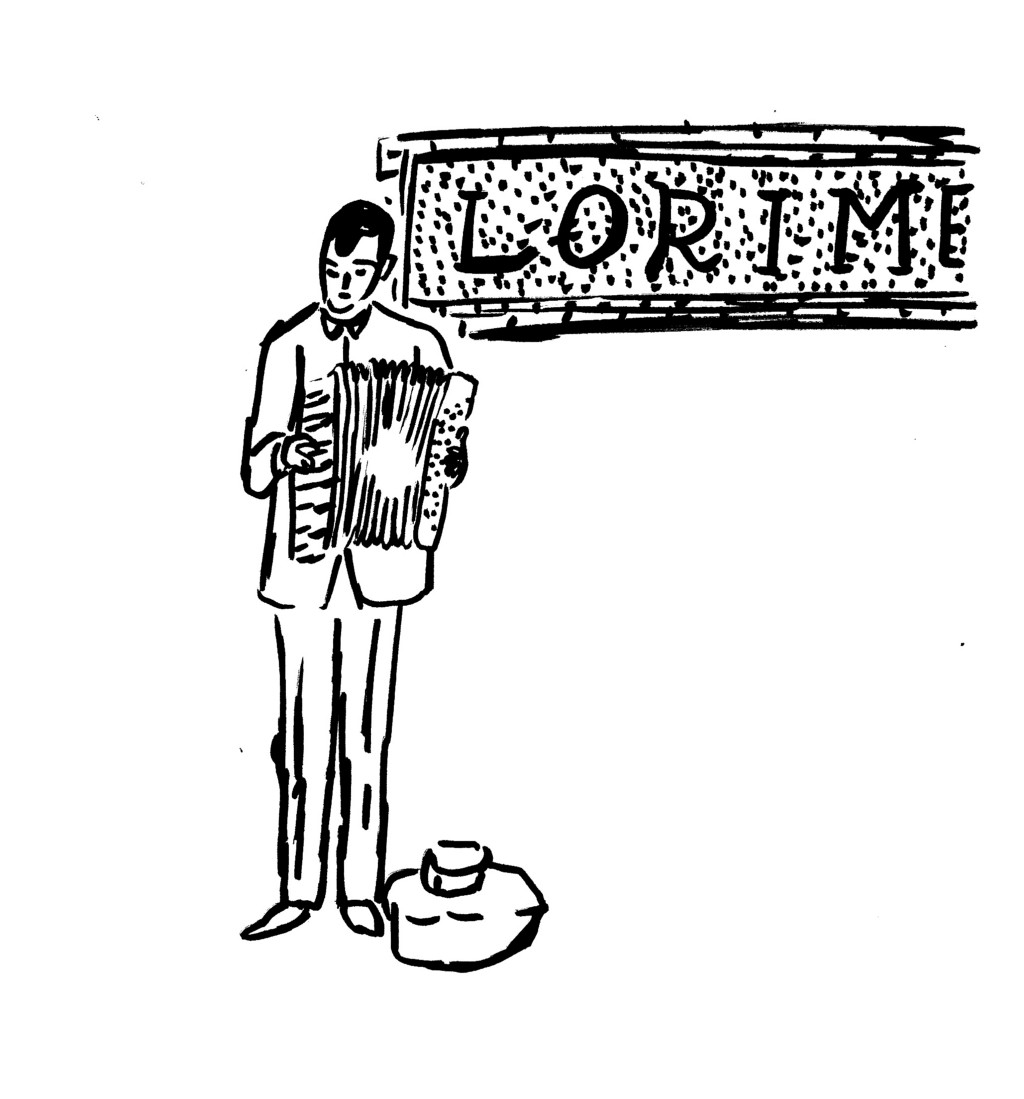

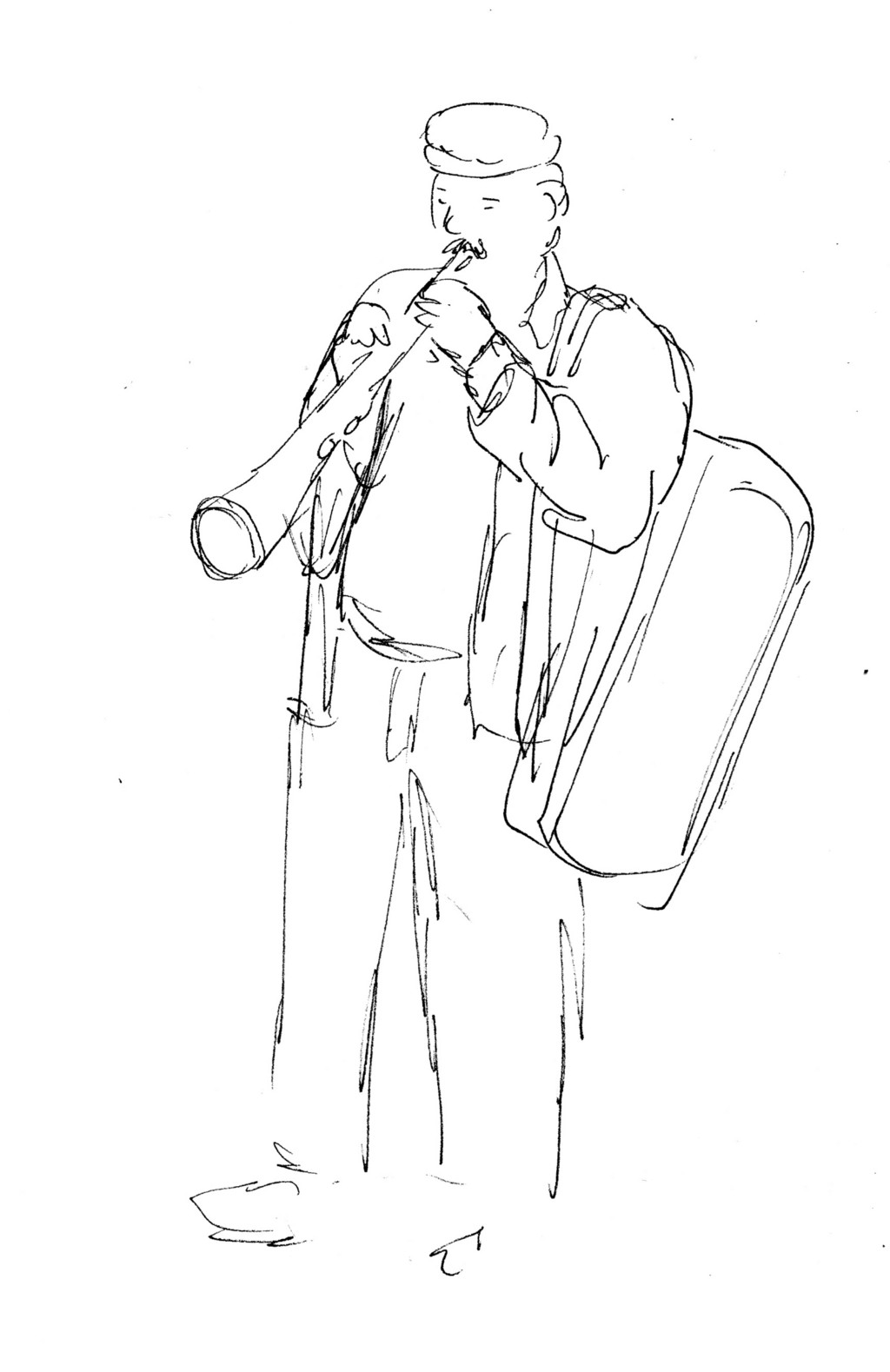

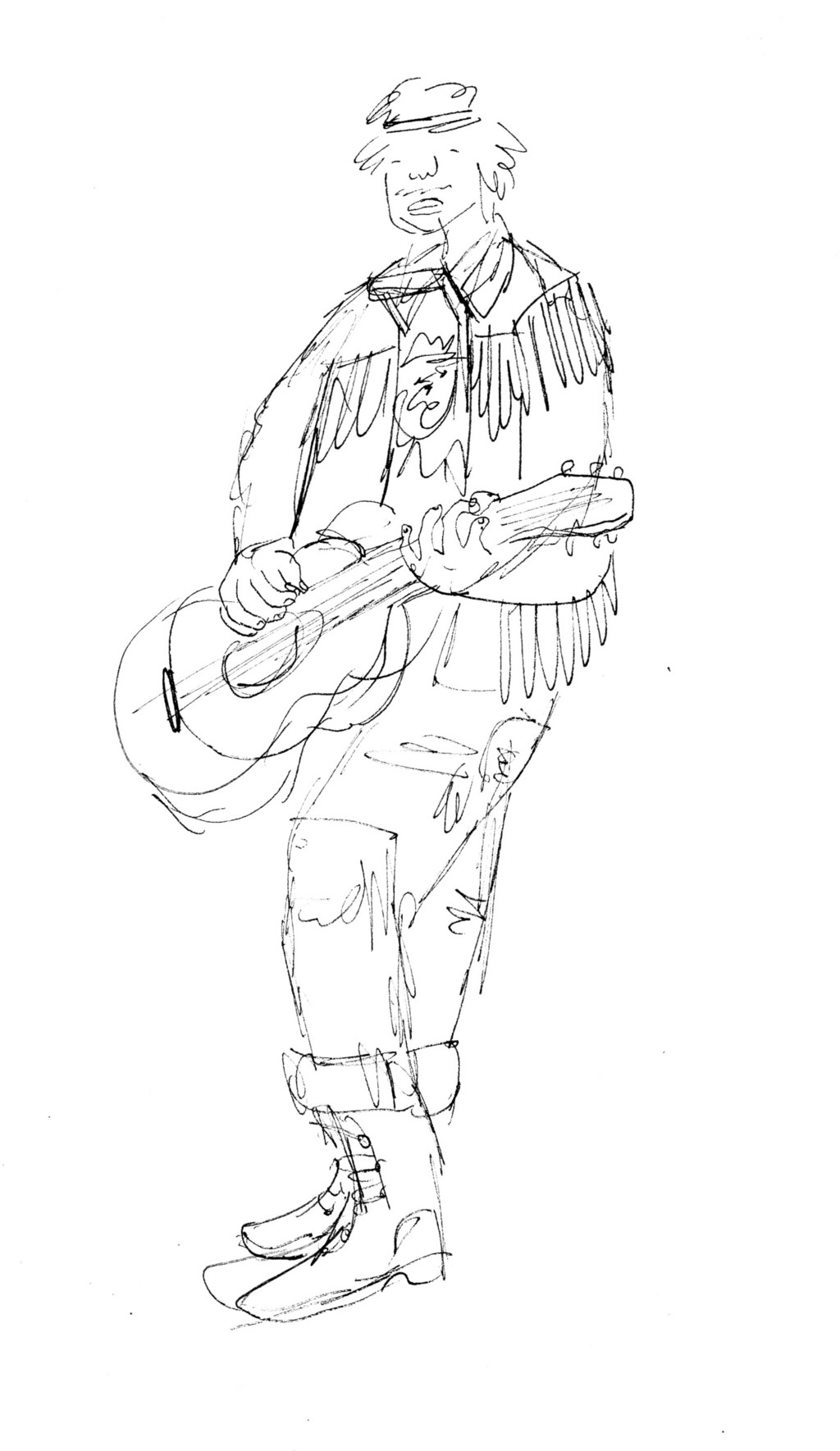

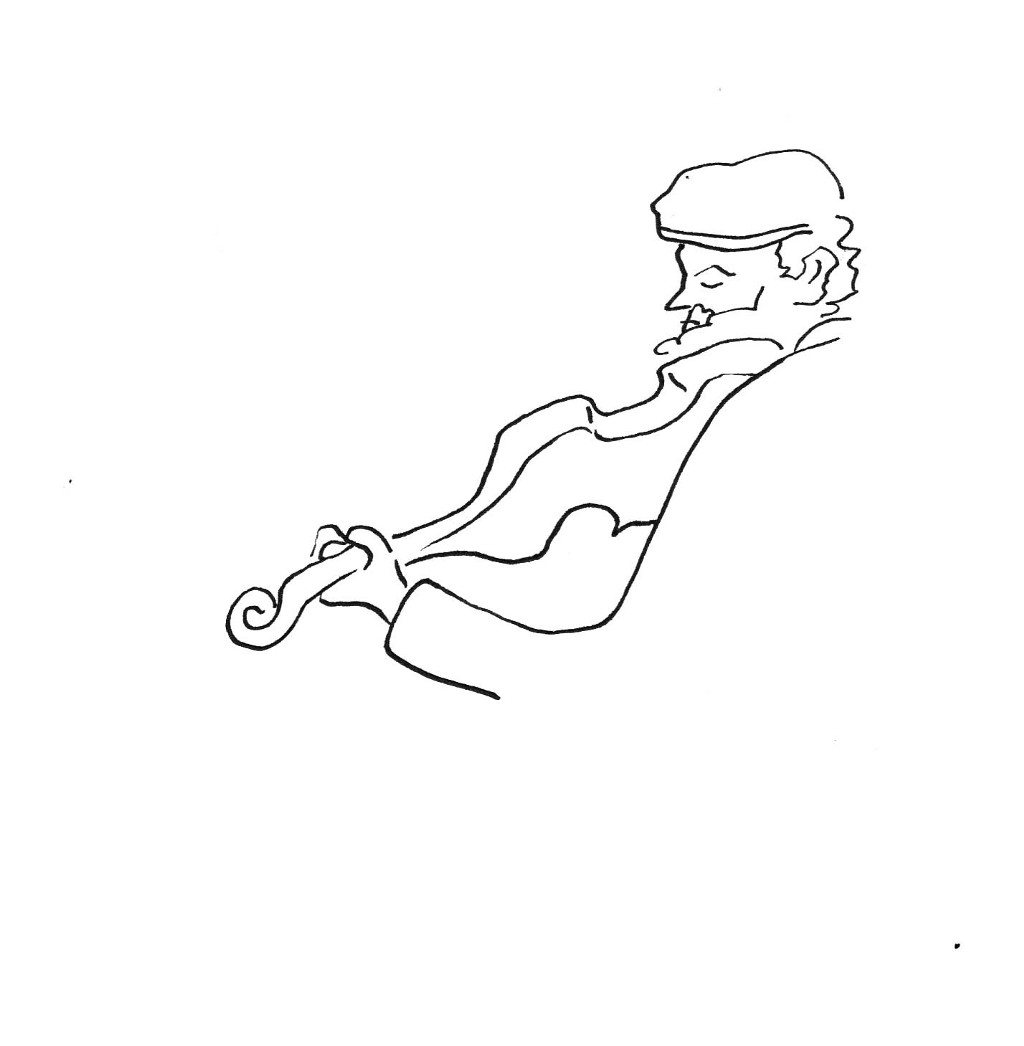

The Songs of the Subway

by Hallie Bateman

I started drawing and recording subway musicians in February 2014, and continued for the rest of the year. This is a selection of the artists I came across. Please forgive me for not formally collecting names and permissions. I was just doing these on the fly, in the middle of my commute, and didn’t think about it.

New York City, July 1, 2015

★★★ It was impossible afterward to remember in what order things had even happened: the flash-flood warning blaring on the phone in the dark, the purple stroke of lightning so bright it shone through the blinds, the bursts of rain clashing against the windows like gravel. By the groggy morning all that was left was dampness and muck, thick air and thin sun. People steered around puddles on the Park walkways. Shiny confetti lay submerged on the sidewalk downtown. All day the clouds were like a finger on a hair dryer’s trigger button, cutting the heat off and turning it on again. The sun went down with cotton-print stripes behind it, cheerful and harmless.

The Workers Behind WeWork

by Brendan O’Connor

Two weeks ago, office cleaners at WeWork locations throughout New York City began protesting unjust working conditions. WeWork is an international co-working startup recently valued at ten billion dollars that is based in New York, where it is, by footprint, reportedly the fastest growing company in the city. The janitorial staff at WeWork’s New York locations are demanding higher wages, benefits, and vacation time; they are also considering joining a union. On Wednesday, they, along with sympathetic union workers from 32BJ (the local chapter of the national Service Employees International Union), and a drum and bugle corps marched from one WeWork location, at 222 Broadway, near Fulton Center, to another, at the Charging Bull, in Bowling Green Park. Speeches were made; the band played; confused tourists looked on.

WeWork cleaners are not employed by the company, but by the Commercial Building Maintenance Corp., which is a non-union shop. They make eleven dollars an hour or less, without benefits; the prevailing wage in New York for union workers is twenty-three dollars an hour, with full benefits. According to 32BJ, ninety percent of commercial office cleaners in New York City — and ninety-eight percent in Manhattan — are unionized. Union members from 32BJ — which claims to be the country’s largest property service workers union, with a hundred and forty-five thousand members, including seventy thousand in New York City — leafleted outside WeWork locations in Boston, Washington, D.C., and Miami, where WeWork just opened. If CBM’s cleaners vote to unionize, they will likely join 32BJ. “Everybody wants to join the union,” Bolivar, a WeWork cleaner, told me.

Bolivar works the night shift at the WeWork space at 120 East 23rd Street. He and two other cleaners have five hours to clean the two kitchens, take out the garbage, mop the hallways, and dry mop the cubicle and office spaces. “We can’t do everything they want us to do,” he said. CBM also expects its employees to cover for absent co-workers whenever and wherever necessary, without paying overtime. “They love to add more work,” he said. For Bolivar, the organization effort is not only about fair compensation, “It’s respect that I would like.” Nobody inside WeWork has said anything to him about the union drive. “It’s business as usual,” Bolivar said.

According to a charge filed by 32BJ with the National Labor Relations Board, a WeWork executive threatened to fire workers who participated in the organizing effort during a meeting with CBM executives held after the cleaners announced their demands. The charge, which can be seen here, claims that WeWork violated the National Labor Relations Act “by threatening the employees of its janitorial contractor that if they unionized, [WeWork] would fire all of them.” WeWork’s only public response thus far has been to deny that the executive threatened to fire anyone. “We absolutely did not and would not threaten the employment of any one who works at one of our locations because of any union activity,” a company spokesperson said in a statement. “Moreover, since all of these individuals are employees of our contractor, we do not even have the right to terminate their employment.” (32BJ spokesperson Rachel Cohen told the New York Observer that the executive’s comments were sent to the union in writing.)

Because WeWork does not actually employ the workers who clean its spaces, the company can abdicate responsibility for how much the cleaners that work at WeWork are paid. Bloomberg Businessweek’s Josh Eidelson calls this the “Who’s the Boss?” problem: “The business models of many major U.S. companies depend on workers who are legally employed by someone else. Labor groups argue that such sprawling supply chains make it harder to hold companies accountable for abuse, let alone organize the workers involved.” However, while it is true that WeWork is not the cleaners’ direct employer, they do choose the company that cleans their spaces — and, at nearly two million square feet in New York City alone, this is a sizeable contract. “WeWork is the decision maker,” Cohen, spokesperson for 32BJ, told me. “They’re in control.”

Not only is CBM the contractor in all of WeWork’s New York locations, but, according to Cohen, CBM doesn’t have any other cleaning contracts with commercial office spaces in New York City. If CBM agrees to start paying their cleaners at the union rate, those charges would get passed up to WeWork; essentially, WeWork chooses whether or not to pay the union rate.

CBM does not employ unionized cleaners. However, one CBM cleaner told me that he’d heard the company’s owner also owns another company that does work with unions. There may be something to this: CBM is headquartered at 200 Oak Drive, #201, Syosset, NY; so is a company called Spanier Building Maintenance. It, unlike CBM, does employ unionized workers. 32BJ, meanwhile, says that it will not stand for WeWork pulling their contract with CBM in New York, regardless of whether it switched to a different, union contractor. “We would not accept any agreement that would not include the continued employment of the cleaners that are there now,” Cohen said. Neither CBM nor SBM responded to requests for comment; WeWork declined to comment.

The charge against WeWork, that an executive threatened to fire organizing workers, is currently under investigation by the NLRB; an initial letter informing WeWork of the investigation was sent on June 22nd. Two days after the letter was sent, WeWork announced that it had raised another four hundred million dollars, at a ten-billion-dollar valuation. At Wednesday’s rally in front of 222 Broadway, State Senator Daniel Squadron expressed disappointment that such a highly-valued business would treat its workers so poorly. “We’re very glad that they’re growing — if they understand that they’re responsible for the jobs they create,” Squadron said. “There’s no excuse for a growing business to come to my district — our city — and undersell our workers.” SEIU-32BJ vice president Shirley Aldebol echoed his dismay. “A company with a ten-billion-dollar valuation is denying workers justice,” Aldebol said. “We can’t allow WeWork to bring in contractors that are going to bring standards down,” she continued, referring to CBM. “We are about raising standards, for all workers.”

In one respect, the insidious brilliance of WeWork is the ease with which it capitalizes on the erosion of any meaningful distinction between work and life and how, through the marketing platitudes and hashtag banalities that sell its members — known elsewhere as tenants — on proximity to a culture of entrepreneurship, it further erodes that distinction. Adam Neumann’s vision for WeWork is not just to create a startup incubator disguised as a series of coworking spaces. “We are not competing with other co-working spaces,” he told Bloomberg. “We are competing with offices. And that is a $15 trillion asset class in the U.S.” Apartments too: WeWork is reportedly exploring a concept called WeLive, wherein WeWork members will live and work in the same WeWork-owned spaces.

Neumann refers to WeWork’s ideal tenants as the “We Generation.” This describes a community of people that “cherishes intention and meaning, a lot of times above material goods,” he says, which is an effective way of selling yourself to budding entrepreneurs and startups who aren’t necessarily making any money (or anything at all). But who, really, is a member of the “We Generation?” And who shares in the sharing economy, and who takes? Who is underneath, cleaning up the mess? WeWork fetishizes the “hustle,” and that’s fine, but what about vacation time and benefits for people trying to support a family in a city that only seems to be getting more and more inhospitable? Who gets to “Never Settle Ever?”

Not everyone, clearly. While reporting an earlier piece on WeWork, an employee of the company who was not authorized to speak to press told me that a man identified as the “head of maintenance” was awarded a surprise cash bonus of several thousand dollars at a WeWork company summit. The point, seemingly, was to express the notion that all kinds of work — not just entrepreneurial work! — are considered valuable in “the We Generation.” This “head of maintenance” is, apparently, a WeWork employee and not a cleaner employed by CBM; the degree of his involvement in the actual process of maintaining the quality and cleanliness of the space is unclear. Asked to verify the identity and position of this individual and whether he received this surprise cash bonus, a company spokesperson told me in an email, “We don’t comment on personnel matters.”

Have you noticed a real estate listing that you would like to have investigated? Send cool tips, fun listings, and hot gossip to brendan@theawl.com.

The Country Bumpkin Circle of Life

by Casey N. Cep

I don’t drink, but if I did, then here’s what I’d say to every bartender in the county: “I’ll just have a glass of anything that’s cool.”

That’s my favorite drink order, and also my favorite pick-up line. It’s a gift Cal Smith gave to the world in 1974. The song was called “Country Bumpkin” and the album was audaciously titled It’s Not the Miles You’ve Traveled. Smith was already a superstar, and this single went into the world between “An Hour and a Six Pack” and “Between Lust and Watching TV.”

“Country Bumpkin” spent a few weeks on the country charts, and the song won Smith both an Academy of Country Music award and Country Music Association award. The quiet ballad of a bumpkin and a barmaid was also my favorite version of love for the first ten years or so of my life — two people who meet and make a family without much fuss. It’s an American love story: A man walked into a bar and “parked his lanky frame upon a tall bar stool” while “a bar room girl with hard and knowing eyes slowly looked him up and down.” Eyes and voices are all it takes to fall in love, and the man’s “long, slow southern drawl” does all the talking. Within a verse, the woman confesses, “I’ve seen some sights, but babe, you’re something.” And then Smith tells us “just a short year later” they’ve married and are welcoming a son into the world, the “cuddly boy child” laying on the woman’s chest while she looks down with “a raptured look of love and tenderness.”

There’s a fullness of life in country songs that’s unrivaled by most other genres. It’s not just that life’s highs and lows are recorded there, it’s that so many of them get gathered into a single song. When Smith sings of “this wondrous world of many wonders,” it’s like Homer sorrowing sorrow, the language itself conveying the completeness of what’s being gathered in the lyrics. One day, it’s “hello, country bumpkin” and then suddenly, too quickly if you’ve done it right, “so long, country bumpkin.”

Someone always dies first, and in this song it’s the wife, leaving her country bumpkins behind. Her family’s sad eyes meet her sweet smile, the woman “knowing fully well her race was nearly run.” Life is full of seasons, and Smith mentions them all with the awkward, unexpected rhyme of “pumpkin.” In the bar, the woman asks, “How’s the frost out on the pumpkin,” and then, only two minutes later, on her deathbed she says, “the frost is gone now from the pumpkin.”

In between are the pleasures of love, the pain of childbirth, and the joys of marriage. “Country Bumpkin” also manages one of the world’s most honest descriptions of a marriage in only six words: “forty years of hard work later,” Smith sings in the flash forward that moves these two lovers along. There’s the work of the world, of course, whatever you have to do with your days to pay the mortgage and buy the groceries, but there’s also the hard work of building a life with someone else.

Strangely, though, the song doesn’t end; it just stops. Smith sings the last verse twice, the woman’s hello turned into a sad farewell, “I’ve seen some sights and life’s been somethin’,” but he stops short of repeating “see you later, country bumpkin.” Smith’s voice fades into an abrupt silence, “the heavy hand of time” not only changing the characters of the song but the voice of the singer himself.

I couldn’t tell you why this song affected me so much as a child. It could be it reminded me of my own parents, although while they’re both country bumpkins, neither spent much time on a bar stool and as much as they wanted a son, they had only daughters. I think it might have something to do with the way Smith’s voice just quiets into nothing. It’s like he knew that the only honest way to end a ballad is by not ending it, but by letting it go on forever.

Country Time is an occasional column about country music.

From Bust To Boom

If we really want to get America’s economy moving again we should arrange a prison break in every state.

A Poem by sam sax

by Mark Bibbins, Editor

Theatre of the Absurd

if you put a bed on stage

you have a bedroom

if you put a sink & two chairs

you have a kitchen

what if there’s only a child

applying foundation to his pristine face

what do you have then?

when a person’s dead onstage

does the audience burn

the scenery or applaud?

does the lighting designer kill

all the lights? though the words

may be the playwright’s

the framework is the inferno’s

furnace dressed in her paper

paper gown. what if the child

disappears into wings

the curtain rising finds

no one left to applaud

what if the child learns

to dance, what if he can’t

my god, what if he tries to sing?

sam sax is a 2015 NEA Fellow and a Poetry Fellow at The Michener Center for Writers, where he serves as the editor-in-chief of Bat City Review. He’s the author of the chapbooks A Guide to Undressing Your Monsters (Button Poetry, 2014) and sad boy / detective (Winner of the Black Lawrence’s 2014 Black River Chapbook Prize).

You will find more poems here. You may contact the editor at poems@theawl.com.

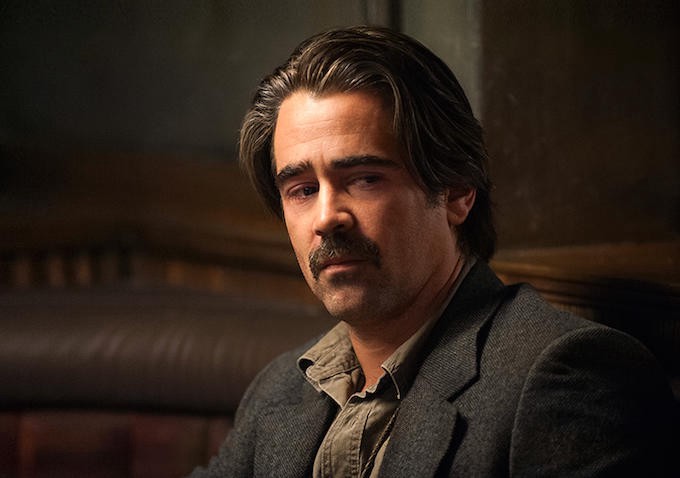

Moments from True Detective Season 2 Episode 2, Ranked

8. Woman says of man’s grisly anecdote, “Sometimes I wonder how many things you have like that that I don’t know about.”

7. Man says, “I’m a piece of shit but that boy is all I have in my shitty life.”

6. Man says to female co-worker, “You pull off that e-cig. A lot of people don’t. …Maybe it’s too close to sucking a robot’s dick.”

5. Sane and caring wife who was raped frets about why her husband is so messed up.

4. Detective stands in ransacked house and says, “Somebody was looking for something.”

3. Psychiatrist wears sunglasses inside, at his desk.

2. Man says to woman, “Sometimes a good beating provokes personal growth.”

1. Man says to woman, “Well, so you know, I support feminism. Mostly by having body issues.”

Songs Summered

No.

This comically incorrect ranking of the Songs of the Summer reminded me that is the twentieth anniversary of the New York Times Magazine’s “The No. 1 Summer Song of Love,” which, if you don’t remember (or weren’t yet literate), goes a little like this:

What becomes a Summer Love Song most? That is a tricky question, for like love itself, the song cannot always be measured by traditional means; both science and intuition play a role in its creation. But there are certain patterns. For instance, the song is usually a ballad and addressed to a universal lover, so that any teen-ager can fill in its “I love you” sentiment afresh, like a blank Valentine card. The song will become a hit, of course, but not necessarily the biggest hit of the summer. It will be neither a dance track (too impersonal) nor a novelty song (too goofy) nor a song with a message (too earnest). If it is a country song or a rap song, it must transcend its genre, because the Summer Love Song turns up at high-school proms and weddings in every kind of American neighborhood. Crucially, the song will feature at its core something indescribably sublime — a bone-deep groove or a lover’s moan — that helps it survive over time. For the Summer Love Song’s true role is to carry the moment into the future, not as history, but as a madeleine of pleasure and heartbreak.

Okay! Anyway, it says here that nothing is going to unseat “Trap Queen” this year and I don’t care how many money-deficient bitches Rihanna has to eviscerate to unseat him.

Generation Gets Celebrities It Deserves

“But the younger Grier’s star is rising swiftly in its own right: His Instagram account, whose shirtless pics and up-close selfies rocketed him to fame less than two years ago, has roughly as many followers — 3.9 million — as those of Neil Patrick Harris and Michelle Obama combined. All told, his Vines — which tend toward Jackass-lite stunts, innocuous physical comedy, and brief snapshots of life on tour — have been looped more than 300 million times. At this point, the Grier brothers are so famous that they can’t go to a mall or amusement park or high school football game without being mobbed. They are so famous that the rest of their family has become famous too, osmotically and apparently without even trying: At the L.A. stop of the tour we’re currently on, dozens of girls (and a not-insignificant number of moms) clamored to take pictures with their father, Chad, better known as “Dad” to many of the fans. Hayes and Nash’s half sister, Skylynn, who’s frequently featured in their videos and photos, has more than 1.3 million Vine followers. She’s 5.”