New York City, July 9, 2015

★★ Here was another dim sky, now with a mist falling from it, in this indefinitely lightless stretch of July. The drizzle stopped; the cool and the flat gray light continued. Now and then the sun found a thin spot and cast a few shadows. A grimy pink haze was swelling in New Jersey. In the quiet of evening, darker clouds were moving fast over the tranquil forecourt, west to east. After the last light was gone, a rain-pecked shine suddenly lay over the pavement.

The Boombox Musical

by Richard Morgan

When a fire destroyed the New York Academy of Music, a suddenly homeless Parisian dance troupe improvised a partnership with an American play. On September 12, 1866, this joint venture, a show called The Black Crook, opened at Broadway’s thirty-two-hundred-seat Niblo’s Garden theater. It broke all the rules: Not only was it five hours long, but it made no distinction between actors and singers and dancers; they all did a bit of everything. It was the first venture into true musical theater and it succeeded wildly, going on for a record-breaking four hundred and seventy-four performances and hauling in a record-breaking million dollars. There were national tours, revivals, and a 1916 movie.

A hundred and fifty years later, a new kind of rule-bending musical is debuting on Broadway, six years after being created as a White House skit. Hamilton, by the thirty-five-year-old oft-goateed Tony-winning wunderkind playwright Lin-Manuel Miranda, is a period-piece retelling of the life of Alexander Hamilton as a hip-hop tragic hero. Miranda, a Puerto Rican, has cast himself in the role of Hamilton; Leslie Odom Jr., an African-American actor, as Aaron Burr; Daveed Diggs, also black, as Thomas Jefferson; and Christopher Jackson, who starred in Miranda’s breakthrough Spanglish musical In The Heights, as George Washington.

Last season, Jackson starred in another hip-hop Broadway play, Holler If Ya Hear Me, the Tupac Shakur jukebox musical (an industry term for musicals like ABBA’s Mamma Mia, Billy Joel’s Movin’ Out, or The Four Seasons’ Jersey Boys, where the soundtrack is composed of previously released music and often comes from a single artist or band) which was widely panned and shuttered after just seventeen previews and thirty-eight performances. “Can you really call it a jukebox musical when it’s Tupac?” Miranda asked me last spring, after a special showing of the movie The Warriors he had put on far, far uptown, at the United Palace. “We need a better word for that, don’t we? Something like a boombox musical.”

Hamilton, which closed a sold out off-Broadway run this spring, may be that boombox musical: Held up as a cure for Broadway’s racial and cultural problems, it has transfixed the largely white Broadway community and its acolytes with less subtlety even than this year’s Academy Awards, which made a performance out of Selma being its centerpiece despite having the whitest nomination list since 1998. From a recording studio in the Heights, Diggs told the Wall Street Journal this week: “It’s sort of ridiculous that it has taken so long for a musical that honors rap music appropriately to come to Broadway. Musicals in the 1920s and 1930s played jazz music. It is odd that musicals in the later part of the 2010s still sound like musicals from the 1960s.” When I asked him about Hamilton’s appeal, he was more politic: “Lin just wrote something we feel really comfortable performing.”

Miranda’s publicist, Charlie Guadano of Sunshine Sachs, declined interview requests, citing an exclusivity agreement with the New York Times, which kicked off its self-described “coronation” of Miranda as the very model of a modern major everything by declaring that “the crucible of American popular theater was the minstrel stage, where white actors blacked up to perform racist caricatures of African-Americans. Hamilton flips minstrelsy on its head.”

The upcoming Broadway season is otherwise about as culturally bold as letting Madonna do the Super Bowl halftime show in her fading fifties instead of her roaring twenties: The Color Purple, The Gin Game, The Wiz, a rumored Do The Right Thing musical. Yes, Taye Diggs is a transsexual East German. And, sure, Shuffle Along stars Audra McDonald, a black actress who holds the record for Tony wins (six!) for a performer. But they are tucked among a revival of Fiddler On The Roof and a play about Prince Charles as king. There’s truth, of course, to the idea that Hamilton is Broadway’s Barack Obama moment — a no-turning-back watershed of cross-culturalism, multi-culturalism, culture in the broadest brashest ballistic sense — but it’s equally true that Hamilton might just be the Tiger Woods of the Great White Way, the Fresh Prince of Broadway. Meanwhile, London theater arguably has been color-blind about its historical casting since 2000, when the Royal Shakespeare Company cast David Oyelowo as King Henry VI; it’s been done.

Four years after the New York Times first reported on a “gay cancer,” playwright Larry Kramer debuted his invective off-Broadway AIDS play The Normal Heart. Three years after Trayvon Martin triggered a new national consciousness about black lives mattering, where are the #blacklivesmatter plays and musicals? Shakur, who has been dead since 1996, was Broadway’s only credited African-American writer last season (ignoring the seven-day run of the combined Four Tops and Temptations concert). There is a bracing, renegade puckishness to Hamilton, but there is also an almost-camp winking whimsy to gangsta rap proffered by men in cravats and spatterdashes. It’s reminiscent of how often West Side Story’s jaunty “America” gets performed by orchestras and marching bands every Fourth of July — without, of course, the song’s jarring lyrics.

In June, at his annual Decades Ball, a fundraiser for Lapham’s Quarterly, Lewis Lapham feted the seventeen eighties and in doing so solicited a telling snippet of Hamilton. Nibbling on smoked pheasant turnovers with warm celeriac and brandy-infused cherry slaw, and quaffing cocktails of gin and violet liqueur, the five-hundred-dollar-a-plate attendees were treated to one of Hamilton’s only non-rap moments: a song performed by Glee’s Jonathan Groff in his role as King George III, a bait-and-switch of Shining proportions. The crowd — skewing as old and white and rich as that at any Broadway show, if not more so — loved it. It was like applauding Barack Obama on Election Night 2008 for his fine taste in his Hart Schaffner Marx hand-cut suit.

Like Silicon Valley or Hollywood — which contractually obligates Spider-Man to be white even as the actual Spider-Man comic book makes him Blatino — Broadway is so rich with white money that it doesn’t need young people or people of color or poor people to survive. Broadway is so white and so whitewashed that Clybourne Park, a play about racial tension over decades, was celebrated for its set design. Broadway is whiter than the Supreme Court, whiter than Harvard University’s student body, whiter than all of France. Its audience — mostly forty-four-year-old white women with a household income of more than two hundred thousand dollars — is twice as likely to be white as the average NBA fan. It can seem like the only black people regularly attending Broadway shows are the Obamas themselves — who have seen Joe Turner’s Come And Gone, A Raisin In The Sun, and, yes, Hamilton. Broadway is otherwise largely the worst sense of black box theater, about as authentic to the modern black experience as, say, Blair Underwood on L.A. Law or Diahann Carroll on Dynasty or Franklin in Peanuts or the entirety of Good Times. It’s no wonder, then, that Hamilton is being championed as a breakthrough moment.

Touching on Broadway’s safety-first, franchise-driven approach to musical theater — Legally Blonde: The Musical, Beaches: The Musical, Groundhog Day: The Musical, American Psycho: The Musical, James Bond: The Musical — Tony-winning composer Jeanine Tesori said in a speech at the Lucille Lortel Awards (the off-Broadway Tonys), “Whenever I think about getting a car, I’m the one saying, ‘Oh! 95 percent of Subarus are still on the road! Maybe we should get a Subaru?’” She added, “Thank God there are those out there proving that musicals can be Maseratis, too. I mean, just look at Hamilton.”

Moments before this year’s Lortels, Miranda greeted me on the red carpet, cheering about “our days uptown.” I asked him again about the Tupac Shakur musical, which had by then been thoroughly eviscerated. “I don’t know their journey,” Miranda said, “but it’s hard to bring hip-hop to Broadway, to bring hip-hop to musicals. Hard to use hip-hop. I love Tupac. I danced to ‘Dear Mama’ at my wedding. And I’m glad they found a way to give his music an audience. But also, guess what? He’s Tupac. The world has already heard his music.”

That analysis came shortly before Hamilton stole the show, sweeping every award for which it had been nominated. The only Hamilton nominations that didn’t win lost out to other Hamilton nominations in their same category. Accepting the Best Musical award, Miranda rapped his acceptance speech, a trick he also pulled at the 2009 Tonys, when he won for In The Heights. “He wrote that on the train,” his father, at an after-party, said of the acceptance speech rap at the Lortels (for the record, George Gershwin composed “Rhapsody in Blue” on a train to Boston). “He’s always doing that,” his mother chimed in, half-proud, half-meh.

Shortly afterwards, Hamilton scored a historic win for Best Musical by the Drama Desk Awards — which don’t distinguish between Broadway and off-Broadway (although an off-Broadway musical hadn’t won since 1983’s Little Shop of Horrors). Hamilton is, in some ways, serving multiple masters — in music, in content, in audience, and, perhaps most importantly on Broadway, in dollars: At the Public Theatre, its off-Broadway home, the show was able to offer ten-dollar lottery tickets (which it’s continuing on Broadway), but for its first preview performance on July 13th, Forbes reported that tickets prices were averaging more than six hundred dollars on the secondary market, with a minimum cost of a hundred and seventy-one dollars. Miranda has brought hip-hop to Broadway in a way that nobody from his neighborhood uptown can afford. “At the Public,” Miranda told me, “there was no stage door. After the show, you walk into the lobby and you see the audience and hear the conversation and feel the energy. You can’t buy that. You can’t fake that. But I’m nervous about bringing that experience to thirteen hundred seats. At the Public, we were kinda hotboxing that shit.”

It’s very early in Hamilton’s theatrical life. But it has a charisma and momentum that defies patience on top of everything else it defies. In that way, its Obama analogy may be truest; people saw a single speech and ached to vaunt a man to the highest office in the land. The worst part of the Miranda-Obama analogy, though, is how both men, talented as they may be, deliver big rushes of excitement only once every four years. They are only human: In 2016, both Obama and Miranda will gather their laurels and exit stage-left. Then what?

Hamilton seems destined for accolades and greatness beyond even Miranda’s wildest dreams. It feels custom-fit to be put on forever and ever and ever by high schools, colleges, and regionals, from now until the end of time. “My man Lin-Manuel Miranda making history in all the right ways,” cheered Pulitzer-winning novelist Junot Díaz (rightfully so) this morning on Facebook, linking to the Times coronation with his own anointing. That’s apt, as Miranda is the Díaz of theater, giving it twenty-first-century teeth.

But Miranda’s crisis is Marie’s Crisis, New York’s venerated singalong piano bar devoted to all things Broadway. On any given night, nearly uniformly white crowds cheerily go through razzle-dazzle ivory-tickling trite-and-true chestnuts from the Broadway canon: Chicago, Les Misérables, Pippin, Rent, and Wicked. But they rarely sing songs from jukebox shows like Mamma Mia or Movin’ Out and, despite its run on Broadway, the arena-rock ballads from Rock of Ages are unspokenly verboten. Is that an atmosphere in which Hamilton can also become canon? Is this crowd — this barometer — going to be spitting Revolutionary War raps in between “Good Morning Baltimore” and “Suddenly Seymour”? That will be the day that the game truly has changed. It’s an uphill fight, but not an impossible one: Just look at the stunning turnaround of that other live performance in town: Saturday Night Live.

Photo from The Public Theater

The Last Trailer Park in Techland

by Andrew Thompson

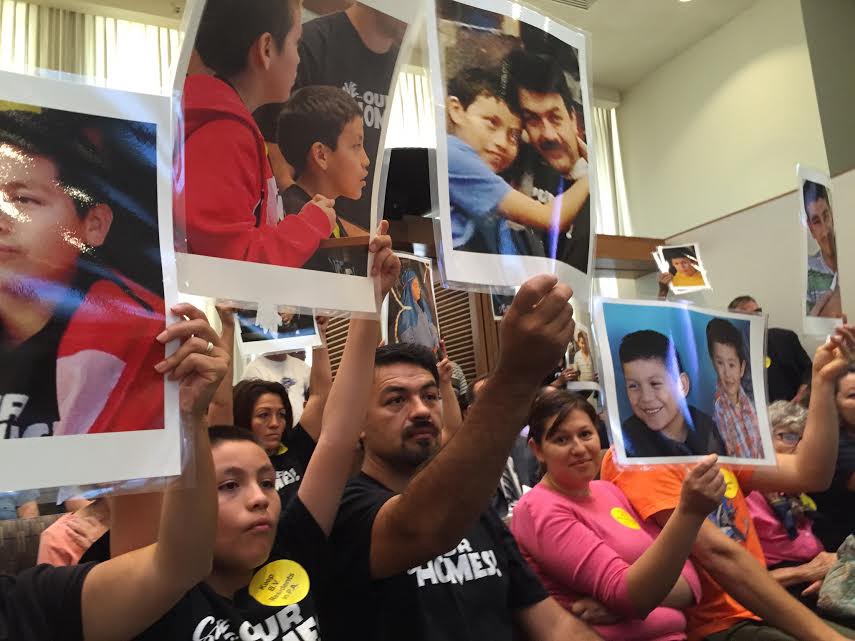

In October 2013, Joe Jisser, the manager of Buena Vista Mobile Home Park in Palo Alto, sent a letter to the park’s four hundred and seventeen mostly low-income, mostly Hispanic residents. It informed them that his parents, Toufic and Eva Jisser, who own the park, were selling the property to a real estate developer. Buena Vista is the city’s last trailer park, and closing it will result in the loss of around a hundred units of affordable housing in one of the most expensive housing markets in the country. The ensuing legal battle became a fractious, public proxy fight over who gets to live in Palo Alto, a city that has been radically transformed by an influx of raw, uncut capital generated at bewildering scale by two technology booms in the past twenty years.

A somewhat arcane city law required the Jissers to pay to relocate the residents to a “comparable mobile-home park.” The Jissers maintained that comparable options existed in nearby towns like Sunnyvale and Redwood City; they offered to pay about fifty-five thousand dollars to each resident to move. Residents argued that any trailer park outside of Palo Alto is effectively incomparable, in large part because of its highly regarded public-school system — which has been a path to the middle class for many Buena Vista residents, like Erika Escalante, a program manager at the Palo Alto Medical Foundation who grew up in the park, and who I talked to last summer. A few months later, in December, a hearing officer appointed by the city sided with the Jissers, allowing them to close the park and relocate its residents outside of Palo Alto with six months notice, a decision reaffirmed by the city council.

But since January, in the background of the appeal hearings, local politicians and philanthropists have rallied to meet the Jissers’ asking price of the four-acre lot and purchase the park, allowing the residents to stay in their homes. By then, Prometheus, the developer to whom the Jissers originally planned to sell the land — and one of the largest developers in Silicon Valley — had already backed out of the process, reportedly turned off by the situation’s poor optics.

Exactly what the land underneath Buena Vista is now worth is uncertain. The Jissers initially rejected a fourteen-and-a-half million dollar offer cobbled together by the park’s residents in favor of a thirty-million-dollar bid from Prometheus. But in Palo Alto, even a figure of thirty million dollars, appraised in 2013, is profoundly outdated. Average housing prices in the past year alone have risen twenty-one percent, and at the current rate, Palo Alto home prices increase on average by about thirty-five thousand dollars per month. Prices move upward so briskly that the City Council, in its most recent decision in May, required the Jissers to conduct a new appraisal.

Buena Vista’s advocates have largely been galvanized around a now-standard Silicon Valley irony — that a region so concerned with “changing the world” is able to so fully ignore the indigence of its own residents. “This would fulfill Palo Alto’s estimation of itself, ‘We can do it, we can do anything, we have fabulous values, we are more innovative than anybody, we can solve problems,’” Winter Dellenbach, a retired civil rights lawyer and the park’s chief non-resident vanguard, told me. “So if Buena Vista doesn’t work out…” she trailed off.

The park’s supporters have quilted together thirty-nine million dollars to buy it on behalf of its current residents: fourteen-and-a-half million from the county (for every square foot of land that Stanford has developed since 1999, it has paid twenty dollars into a county fund for the development of low-income housing within six miles of the university); fourteen-and-a-half million dollars from the city, in matching funds; and ten million in the form of a tax-exempt bond from Caritas, a nonprofit that manages low-income mobile home parks, and which would likely manage the park if it was successfully purchased from the Jissers on behalf of its residents.

With additional fees and other anticipated costs, the total amount needed to purchase Buena Vista is stands at more than forty million dollars — at least three hundred forty thousand dollars per trailer — and could rise by millions more, depending on the outcome of a new appraisal. To raise additional funding, a local foundation has contacted several local tech plutocrats in the hopes that their charitable interests might align with Buena Vista’s needs.

The question of whether or not it’s worth it is really a question of, “What would this cost to replace this affordable housing unit if we lost it from our stock?” Joe Simitian, a local politician-of-all-trades who, at various points, has been Palo Alto’s mayor, state senator, and is now its county supervisor, told me. He pointed out that an affordable housing project built in 2014 that took a decade of politicking and fundraising to develop provided fifty units of housing at six hundred thousand dollars a unit.

No matter how much money supporters raise, the whole deal is, of course, contingent on the Jissers accepting the offer. Neither Jissers nor their lawyer could be reached for comment. “I’m in regular contact with the property owners,” Simitian said, adding that the decision to allow the Jissers to close the park was made on May 26th, “and Mr. Jisser and I were in my office the next morning at 10 o’clock. We’ve probably met four or five times in the intervening months. We talk on the phone. He wants to shop the property and get sense of what the market is for his property. But we talk and we’re still talking.”

Photo by Melody Cheney

Wait, Now Smoking's Bad For You?

“One of the reasons we have not yet banned nicotine outright in this country,” a brilliant social theorist declared several years ago, “is that it is the cheapest treatment for anxiety that we have, in the sense that majority of the people suffering from the mental issues that are somewhat soothed by nicotine will pay for the drug without any kind of government or employer subsidy, and if we actually got rid of cigarettes the true cost of treating everyone who doesn’t even know that they’re smoking to be less sad would maybe break the country.” But what if smoking actually causes schizophrenia? “61 separate studies suggests nicotine in cigarette smoke may be altering the brain,” which experts call a “pretty strong case,” so I guess that’s that. Don’t smoke to keep yourself sane anymore, it’s only making things worse. (Also, pain medications will heart attack or stroke you, no matter how good they taste. Pain, it turns out, cannot be prevented; only postponed.) Sorry, smokers. The good news is it that quitting smoking is not impossible; why, the New York Times recenty told the heroic tale of a man who somehow managed to pull it off. There’s hope for you yet! I mean, unless you have a headache or your back hurts.

The Andrew Cuomo Apology Tour

“Confronted with a restive party, Mr. Cuomo, 57, now faces the most consequential political choice of his second term: whether to appease downtrodden Democrats by adjusting his personal style, or to continue relying on a set of hard-edged methods that his supporters call essential to maintaining political order in the state.”

Julia Holter, "Feel You"

Tragedy, Julia Holter’s debut, was released at the end of 2011, so she still feels “new” to me, but she’s not. She’s not new. 2011 was almost five years ago. The minutes and hours days and months keep passing us by, and they are rapidly gathering speed. The plodding pace at which time once advanced has now accelerated at an almost incomprehensible rate and we hurtle inexorably toward death without a chance to catch our breath or clutch a current moment to our chest. In just a second your future will be written on a page you have already flipped past and all your hopes and fears will come to nothing. Your life is written on water and the water drains away. Julia Holter’s fourth album, Have You In My Wilderness, is out at the end of September. Enjoy.

New York City, July 8, 2015

★★ Umbrellas were out for no real reason; whatever drops were falling were indistinguishable from the usual ambient blowing liquid. Sparrows tumbled under the low bottom bar of the playground fence, fighting or coupling. The sycamores had been dropping shreds of bark on the green concrete. A platoon of older kids in swimsuits swarmed the fountain, some of them grappling in the spray. The northwestern sky blued a little. The three-year-old came running up, bright-eyed and intent, to report collateral damage from someone’s water balloon. By the three o’clock hour, gloom had taken over.

Room Versus Board

by Brendan O’Connor

On Monday, an anti-Airbnb advocacy group called “Share Better” released a minute-long satirical video titled “Save the Moguls.” It’s a parody of the charity-drive commercial genre: There’s a female voice-over, a sparse piano-driven score, and downcast subjects, whose strife your money can alleviate. In this video, however, instead of homeless people or animals, the subjects are something called “real estate moguls,” and rather than a donation, the real estate moguls need the booking fees that they collect when you stay in their de-centralized hotel, distributed across Airbnb. It’s not that funny. But that’s okay! Being funny isn’t the point; it’s that the people benefiting most from Airbnb aren’t the hosts or the guests, but the arch capitalists overseeing the whole sharing-based affair. Of course, Airbnb rejects this premise. “This ad is dishonest and the hotel industry lobbyists who paid for it should know better by now,” an Airbnb spokesperson said in a statement.

In New York, it is illegal to rent out an apartment for fewer than thirty days if you — whether owner or tenant — are not also present in the apartment. It is not surprising, then, that according to data provided by Airbnb to New York State Attorney General Eric Schneiderman under subpoena last year, nearly three quarters of Airbnb listings in New York between January 2010 and June 2014 appear to have been illegal. But that, in and of itself, doesn’t tell us much; the law that defined these parameters was passed in 2010, before Airbnb was as ubiquitous and successful as it is today. (It was intended for a wholly different purpose: to crack down on operators who crammed people into unsafe and unclean spaces.)

Airbnb’s statement continues: “Ninety percent of Airbnb hosts in New York simply rent out the home in which they live.” While this is probably true, without more information about the rest of Airbnb’s hosts in New York, it is mostly meaningless. According to the data Airbnb provided to the attorney general, six percent of hosts accounted for thirty-seven percent (a hundred and sixty-eight million dollars) of all host revenue in New York. The AG refers to these hosts as “commercial users,” defined as hosts who list three or more unique units. According to the report, the single most successful Airbnb host in New York “controlled two hundred and seventy-two unique units and received revenue of 6.8 million dollars. This individual received two percent of all New York host revenue for private stays and personally earned Airbnb close to eight hundred thousand dollars in fees.” Altogether, the top twelve hosts on Airbnb — commercial users, all — controlled eight hundred and one unique rental units, accepted over fourteen-and-a-half thousand reservations, and generated more than 24.2 million dollars in revenue. Airbnb declined to answer questions about how much of their revenue is presently accounted for by the ten percent of hosts who do more than “simply rent out the home in which they live.”

“This is a story of personal empowerment and benefits to the city; no amount of advertising will convince New Yorkers to choose hotel industry moguls over regular people,” Airbnb’s statement about the video concludes. In fairness, “real estate moguls” may have been overstating the case, but Airbnb’s framing the issue as a choice between “hotel industry moguls” and “regular people” is just as egregious an overstatement. Per the AG’s report, thirty-eight percent of all fees Airbnb received in 2013 were generated by apartments that were booked, cumulatively, for six months out of the year or more. That is to say: These apartments were taken off the long-term housing market, shrinking an already diminished supply of housing in order to meet the demand of people who don’t actually live here.

In January, Airbnb executives made a contentious appearance before the City Council to answer questions about illegal listings on the platform. “The representatives from Airbnb were so difficult and were evasive in some ways and at times too cute by half,” Councilman Mark Levine told Crain’s New York afterwards. Later that month, the De Blasio administration began enforcing the ban on illegal rentals more strenuously than it had: According to the New York Daily News, during the first four months of 2015, the Office of Special Inspections issued five hundred and sixty-eight violations to illegal hotel operators, as compared to three hundred and ten during the same period in 2014. De Blasio has proposed doubling the office’s budget for 2016. In February, Public Advocate Letitia James released a list of the thirty top illegal hotel operators in New York City. Since 2011, the top three operators, High Point Associations, M 317–319 Realty, and Lighthouse West 49th St LLC, were all fined tens of thousands of dollars. In that time, the city fined the top thirty illegal hotel operators seven hundred and ninety-six thousand dollars altogether. In June, legislation was introduced to the Council that would increase first-time fines for illegal hotel operators from a thousand dollars to ten thousand dollars and increase the maximum from twenty-five thousand dollars to fifty thousand dollars.

Airbnb is not wrong about the source of funding for the ad: Share Better is backed by the Hotel Trades Council, the large and powerful New York hotel workers union. In the fall, Capital New York reported that Share Better planned to spend around three million dollars on its anti-Airbnb campaign; in March, Crain’s New York reported that Airbnb spent fifteen million dollars on television ads in the second half of 2014, while billboards and subway ads cost millions more. According to New York state disclosure records, since 2010, Airbnb has spent at least two hundred and eighty-one thousand dollars lobbying members of the legislative and executive branches at both the city and state levels; In the same period, the Hotel Trades Council spent at least three hundred and twenty-five thousand dollars — almost half of that in 2014 — lobbying the same people on issues specifically pertaining to illegal hotels. (The HTC spent much more than that altogether.) All of which is to say that, while clearly it is true that Airbnb faces stiffer resistance in New York than it has mostly anywhere else, the company, which is reportedly raising one billion dollars at a twenty-four-dollar billion valuation — a number that would make the company more valuable (theoretically, anyway) than giant hotel chain Marriott International — is not exactly punching above its weight.

Any company that valuable, too, is bound to pull other entrepreneurs into its orbit. One start-up whose business is contingent upon Airbnb’s continued success if Proprly: a cleaning and key delivery services for hosts and homeowners. “Airbnb is changing the landscape. It’s changing the way people view space,” founder and CEO Randy Engler, told me on the phone, speaking from California, where he lives, although his company is based in New York. “People have been using space illegally forever. Airbnb is just the first to do it so boldly.”

Proprly keeps in close touch with its progenitor. “It’s not a true partnership, but we keep close tabs on each other. It’s mutually beneficial to understand what the market is doing. When you’re a large company like Airbnb, it’s hard to understand what’s going on at the ground level,” Engler said. The company’s couriers and cleaners, Engler told me, are all contractors; mostly, they set their own schedules, and appreciate the flexibility. What Proprly and Proprly’s workers are doing is ensuring that there is another layer of quality control — should hosts avail themselves of his company’s services — in the Airbnb experience. Many of the company’s couriers, for example, are aspiring actors and actresses, Engler said. This means they know how to be cordial, friendly, and warm. Many are also multilingual, which puts international visitors further at ease. “If you’ve travelled internationally, you know when someone is really welcoming you, and when they’re just going through the motions.” What Proprly offers, Engler said, is “a really great front-desk experience, which is something that hasn’t really been done before in the sharing economy.”

A 2014 Fast Company magazine profile of Airbnb co-founder Brian Chesky describes his “eureka” moment:

During the winter of 2012–2013, he stumbled upon the introductory textbook on hospitality taught by Cornell’s hotel school. After reading it, he thought: This is what we’re missing! The story starts to sound a tad too neat when Chesky says there wasn’t a specific lesson from the 500-page text that grabbed his imagination; rather it was the whole book that crystallized the simple idea that hospitality should be at the core of what his company provides. Airbnb would no longer be about where you stay, but what you do — and whom you do it with — while you’re there.

Elsewhere, Chesky claims, “Our business isn’t [renting] the house… Our business is the entire trip.” In other parts of the world, this might be called owning the whole stack or vertical integration. Meanwhile, real estate investor Thomas Barrack is quoted in Fortune magazine, in April: “[Airbnb] is killing [the hospitality industry], of course. If you look at the hospitality industry… you have to adapt the regulatory environment, the tax environment, all of the local handicap requirements… keeping full-time employees. You just impute that on capital structure, versus a non-asset intensive engine of management, you can’t compete.”

The true innovation of the sharing economy — or maybe it’s the startup economy, or entrepreneurship (or maybe just…capitalism) — is in the continued refinement of the perception of value, not necessarily in offering new services and developing new products, but in making them available for cheaper, because, as it turns out, when you don’t pay anyone a salary or give them benefits because they’re all subcontractors, and you don’t actually have to invest in any of the infrastructure upon which your business model depends, either directly or by paying taxes, your costs are a lot lower than everyone else. “It’s New York: it comes down to money,” Engler said. “It’s super complicated, but it’s also simple: it comes down to making sure everyone gets a cut of this great thing called Airbnb.”

Have you noticed a real estate listing that you would like to have investigated? Send cool tips, fun listings, and hot gossip to brendan@theawl.com.

Public Waterworks

As with so many other things in life, Kim Kardashian is the gold standard against which we measure the ugliness of our crying faces. Among Kim’s endless portfolio of magazine covers, red carpet looks and high-fashion shoots is a collection of equally popular photos of the celebrity in hysterics — mouth agape, makeup still intact (thank God). The most iconic image of the crying Kardashian comes from an episode of “Kourtney and Kim Take New York” when she laments her failed marriage to Kris Humphries. This screencap is now purchasable in nearly every form, with Kim’s floating head appearing on t-shirts, earrings, phone cases, pillows and clothing.

Of course, Kim had no choice in the matter; she hasn’t known a private moment since Keeping Up with the Kardashians started airing in 2007. Yet many of us choose to forego our own privacy and take photos of ourselves crying, catapulting them onto our Instagram, Tumblr, or Facebook accounts. On the night before our college graduation, my friend Ben, with tears streaming down his face, asked, “Can we take more crying selfies?” Millennial vanity would be a trite explanation for this phenomenon; by making our grief public, we let ourselves and others know grief is not felt in isolation.

Crying in public becomes less acceptable as you grow older. This is one of the things I envy babies for most: It’s permissible for them to wear pajamas in public, to fall asleep anywhere, and to cry at any moment. But big girls don’t cry — except at the grocery store, at the bank, or on the subway. Since most of city-dwellers’ lives are spent in public, and there’s only so long you can hold it in, whatever it is, cities are breeding grounds for public displays of emotion. A hotel in Tokyo has found a way to capitalize on this problem, offering crying rooms stocked with sad-girl necessities: tissues, eye masks, make-up remover and an array of melancholy movies.

Still, New York City distinguishes itself as the capital for crying in public. The New York Times, Gothamist, and New York magazine have published ruminative Op-eds and comprehensive crying guides complete with gloomy playlists on the subject, providing tips for repeated offenders (always carry sunglasses) and suggesting places that might offer temporary respite for the tearful (parks, department stores). A Tumblr account called Crying New York has dedicated an entire website to the cause. Stare at yourself dramatically in a city puddle, the blog’s founder, Kerry O’Brien, suggests, while the daring may opt for weeping atop a double-decker tour bus in the rain. Cry on the S Train; it only has two stops. The world is your fainting couch, that free tabloid, your handkerchief. One day New York might catch up with Tokyo.

When a woman is seen crying in public, a few things might happen to her. If she’s lucky, she’ll be ignored. Though we often lament the stone-faced New Yorker, intent on getting to their destination with minimal human interaction, here is where they shine: They leave the crying person alone. In a moment where stress, frustration, sadness — or, in many cases, all three — reach a pressure point, the last thing we want is to have to assure a crowd of strangers, we’re okay, we’re okay, we’re okay. (For better or for worse, men who cry in public are nearly invisible, since society doesn’t know what to do with crying men anyway.)

If, like me, the crying woman is unlucky, she’ll be swarmed by kindhearted strangers. These are the same people who say “sorry” when they bump into you on the sidewalk or hold the doors open as you run toward the subway train about to pull away. But here, their kindness is misplaced. Usually, there’s nothing you can do to help the situation; better to let the weepy have a private moment. Consider public crying the equivalent of a “do not disturb sign,” a shade drawn over a window.

Evolutionarily speaking, the reasons why anyone cries are pretty paper thin. It was long thought that crying had no evolutionary purpose at all. Sure, we need tears to clean and protect our eyes, but why should they have any emotional meaning? Randy Cornelius, a professor of psychology at Vassar College, told NPR that there are a few theories. “Crying may have evolved as a kind of signal,” he said, “a signal that was valuable because it could only be picked up by those closest to us who could actually see our tears. Tears let our intimates in — people within a couple feet of us, who would be more likely to help.”

But if this is true, crying in public is certainly useless. Instead of opening ourselves up to family or friends who understand our sadness or can at least provide words of comfort, crying in public is to offer ourselves up to unsuspecting strangers. Most of them are uninterested in our tears, and that’s fine. Let the tears come; New York is hot, the G train will be down, and the line for cold-brew iced coffee too long.