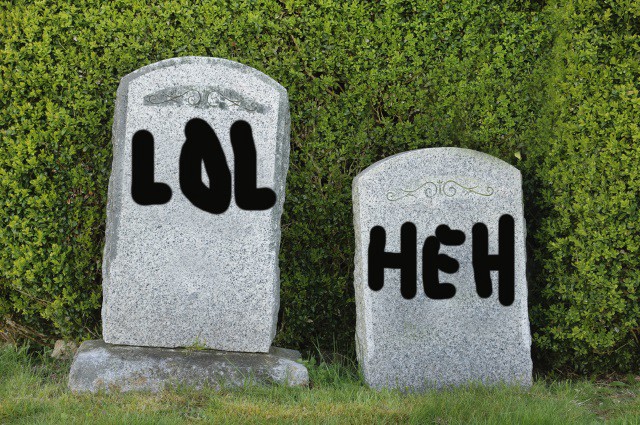

The Death of lol

“A new report from Facebook into how users express laughter shows that ‘haha’ and its variants are by far the most common terms used on the social network. They accounted for 51.4 percent of mirth in the anonymized comments and posts looked at by Facebook’s data team, with laughter emoji claiming 33.7 percent, and ‘hehe’ and its cognates 13.1 percent. The once-mighty ‘lol’ only appeared in 1.9 percent of the text sampled by Facebook — a pretty staggering fall for an expression that was once synonymous with online txt speak. Although not surprising for such a venerable term, ‘lol’ proved slightly more popular with older users. Differences between generations were not heavily pronounced, but it was emoji that were most popular with users with the youngest median age, while ‘haha,’ ‘hehe,’ and ‘lol’ were favored by progressively older individuals.”

— As a confirmed “hahaha” man myself — and, more importantly, as someone who has always read “lol” as vaguely hostile or sarcastic — my joy at lol’s passing is only tempered by the knowledge that pretty soon all written communication, even idiot acronyms whose ambiguities are only amplified by the lack of tonal clarity textual conversation provides, will be superseded by those stupid smiley faces so popular with the kids. Thank God our post-literacy world will only last a little longer before we’re running from fires and eaten by robots.

Photo: Shutterstock.com

Your New York City Horoscope

Did I ever tell you about my subway horoscope column idea? The premise was essentially that you could forecast someone’s weekly commute in the same way astrology forecasts offer, uh, guidance for their personal and professional week. Your subway sign would be your usual station of origin and then the most common transfer or destination of your trip, i.e. “I’m an F with a 6 rising.” Each week you’d get something like, “Ls should plan to spend a lot of time near home for the next few days” or “Rs with a special someone who shows a J rising, this is when you need to make your move!”

Sadly, and as is the case with most of my ideas, it fell apart in the execution stage: To really pull it off you’d need someone with enough of a grounding in both the intricacies of our transit system and the astounding bullshit that is astrology, a commonality unlikely enough to start with, let alone one that could be found in someone articulate and willing to write essentially a one-note joke of a column. Impractical as it may be, I still hold a place for it in my heart (along with some of the other, better ideas I have never managed to get implemented here, like the Doody Car story) and hope that someday, somehow it might happen. Why do I bring it up?

There are about a million walking tours you can take in New York City. But there’s only one (that we know of) that’s is tailored to your astrological birth chart. That’s the premise of the expedition around the city that Bess Matassa will plot out just for you. The astrologer and urban cultural geographer plans expeditions that take her clients to sites that embody qualities expressed in and absent from their charts, which document the position of the sun, the moon and the planets at the time of and in relation to the place of their birth.

Well, I guess, good for her. In the meantime, if you feel like you could make my subway astrology column a thing that works, please get in touch. It should probably be much easier now that all the trains suck all the time.

Moments from True Detective Season 2 Episode 8, Ranked

13. In his final act of bad parenting, man is revealed to have given his ten-year-old son an email address that is the son’s real name.

12. Man proposes a heist to solve all of the problems that solving the case of another heist caused.

11. Man puts the weight of his badness on his son: “I’m sorry for the man I became, the father I was… I hope you got the strength to learn from that.”

10. Man tries to turn his wife out by saying, “If you can’t have a kid what good is the design, see?”

9. In his final moments, man hallucinates about the time he was mocked by his father and… a group of black youths.

8. Man refers to the act of news breaking with a stunning new metaphor: “shit hits the cloud.”

7. Man’s voice recording won’t upload from his phone even though he has 4/5 bars of reception. Must have been AT&T.;

6. Man and his phone’s data connection die together in the woods. It was definitely AT&T.;

5. Woman tells man he has sex like he “was making up for lost time.”

4. Man describes another man who has tortured and killed several people through the course of the show as “actually not a bad guy.”

3. Woman says, “My life ended that day.” Another woman responds, knowledgeably, “No it didn’t.”

2. Man voluntarily gives up a million dollars, but literally dies on the hill of having to give up his suit.

1. Woman says “We’re going to talk again right?” Man responds, “Are you kidding me? You’re going to need a restraining order.”

Barnaby Carter, "Partizan Belgrade"

It seems like spring wrapped up just seconds ago and yet at the end of the week it’s the middle of August and your summer is set to start circling the drain. You’ve wasted another one, haven’t you? You’ll open your eyes one morning and suddenly find fall fully on, all the irresponsibilities you neglected this season now distant regrets over bad decisions not made. Sure, you’ve still got a few weeks to do something stupid, but the stupidest thing you’ll do is let torpor take over, and the one thing we know about torpor is it loves Hulu and Seamless and staying in nights. Maybe next summer will be better for you? Hahaha, no it won’t. Anyway, it’s Monday. I’m not going to tell you that this song will take the pain away because nothing can do that. But for about five minutes it will let you focus on something else, which is really all you’ve got going for you now. Enjoy.

David Nobbs, 1935-2015

“Writer David Nobbs, best known for creating the television character Reginald Perrin, has died, the British Humanist Association has said. Nobbs, 80, from Ripon, North Yorkshire, also wrote for The Two Ronnies, Ken Dodd, Frankie Howerd and Radio 4’s The Maltby Collection. The creator of The Fall and Rise of Reginald Perrin also wrote 20 novels.”

— It’s probably right that Reginald Perrin is the first line in his obituary, but Nobbs’ Henry Pratt character is a sweeter, warmer and more human creation, without sacrificing any of the humor that made Perrin so delightful. You can pick up a cheap omnibus of the first three Henry Pratt books here; the first three Perrin books are here. I’m not sure where to find the television series but I don’t doubt if you’re clever enough it is streaming somewhere. Nobbs was 80.

New York City, August 6, 2015

★★★★ Thin clouds were on the sun again; again the morning air was cool. It seemed possible that the summer might have moved past its sweltering height, that the calendar and the planet’s axis had made irrevocable progress toward the autumn. Two helmetless children rode little bikes up the sidewalk of Fifth Avenue. The sun moved through pickup time, keeping its light cloud escort. Its descent looked unassuming, another unremarkable sunset — until bits of sudden bright and weird color began appearing: a flare of hot coral inside the latticed superstructure of the old apartment slab, pink and yellow bands in the northwest, a pale blue wake behind a boat on the otherwise indeterminately tinted river. Bigger stripes formed, dark and seemingly settled purple, chased unexpectedly with a late-arriving hot pink.

The Bachelor Delusion

by Batya Ungar-Sargon

Is a show built around a successful woman who makes good money and is good at her job a feminist show, even if said job consists of commodifying other women? How much of a feminist can you be if you routinely manipulate women into making fools of themselves for profit, or worse, for the sheer pleasure of being good at it? Is that a sign of illness, or of female empowerment? These are the questions at the heart of Lifetime’s new show, Unreal, which is simultaneously the most and least feminist television show on air.

Unreal, which just wrapped its first season, takes place on the set of a Bachelor-esque reality show called Everlasting, which, like its reality TV source material, pits tens of women in a competition for the love of one man. Unreal centers around the lives of Everlasting’s producers, those elfin presences who encourage and enable the self-destructive behaviors that make for great reality TV by any means necessary.

The show wastes little time with throat clearing, its shots skipping back and forth between the set of Everlasting and the dark control room lair where its producers watch the footage on big screens and shout out orders (“We’re producing true love, people!”), but the third episode is where it reveals the stakes. Cutting between an argument producer Rachel Goldberg is having with her mother and scenes of women driven wild by the producers’ crass exploitation, the show goes after the source of Rachel’s talent. Her mother insists that Rachel has an undefined psychiatric disorder (it’s either ADHD, narcissistic personality disorder, or bipolar, take your pick!). “The reason you’re so good at what you do — the manipulation, the attunement — that is the disease!” Cut to a scene of some women getting into a catfight because Rachel thoroughly manipulated them. “There is nothing wrong with you,” her boss, Quinn, played by a magnificently cast Constance Zimmer, purrs over a shared cigarette as she and Rachel sit back and watch the catfight unfold. “You’re a genius.” The show returns to this question again and again: Is manipulation a talent, or an illness? And by doing so, points at what it thinks keeps viewers coming back to The Bachelor, season after season.

Here’s how The Bachelor works: Twenty-five women are gathered in a secluded mansion. They are there to compete for the love and commitment of one man, the titular bachelor, who winnows down the group through dates — both group dates and one-on-one dates — and the weekly rose ceremony, where he calls their names one by one until there are no roses left; those not awarded one are sent home. Twenty-five women date one man until it’s down to the final ten, the final six, the final two, and then the one.

But the competitive aspect of The Bachelor has, in recent seasons, been radically disavowed. The show is now more often framed as a journey for love, the formerly synonymous goals of pursuing passion and destroying the competition heavily contrasted throughout the season. “Are you here for love or are you just here to win?!” is a question contestants often hurl at each other; being on the show “for the right reasons” is a constant source of drama. What are the right reasons for being on a reality show? It’s a good question, one asked by Rozlyn Papa after she became the first contestant to be booted off The Bachelor for making out with a producer. They can’t be to win, that’s for sure: The contestants are put in the position of maintaining the show’s fiction for an audience who know better by now; they must act like going on a reality TV show is merely an unfortunate byproduct of a completely honorable pursuit, a quest for true love. It’s part of what makes the show work; contestants who seem too canny (like last season’s Kelsey, who bragged that her husband’s death was “such a good story, right?”) are booted off with much fanfare.

Unreal’s gambit is to traffick in the aesthetics of reality shows like The Bachelor — its show-within-a-show, Everlasting, is every bit as misogynist and compelling as The Bachelor — while providing the viewer with a potential alibi: that by making the scaffolding of the industry visible around the margins of the show, it proffers a compelling critique of shows like the The Bachelor.

But the nugget of Unreal’s excellence lies in the complexity of its treatment of women. While it certainly understands and exploits the sumptuousness of cat fights and beautiful women with competing goals, everyone — including the sexy, slutty contestants — is awarded plausible goals, and very few of them include love or romance. One of the contestants is gay and wants the “suitor,” Adam, so she can continue her affair with her secret lesbian lover; another is on the show to get recognition for a hair product line; most just want to be famous; and others just want to win. No one seems to actually want a life with Adam. And while viewers of The Bachelor enjoy consuming the self-destructive behaviors of people with flaws just like their own — the desire to be famous, the hunger to be loved — Rachel and Quinn, Unreal’s anti-hero protagonists, enjoy inducing those behaviors, because they make for good TV. The broader tension in the narrative derives from whether the show can get us to root for women who would manipulate and even destroy other women. In other words, the show fully expects its viewers to see producing the sexist tropes of Everlasting as on par with other forms of bad behavior that we forgive in compelling and charismatic male protagonists. It works: In the first shot of Rachel, she’s lying on her back in a limo conveying six women to meet their Bachelor, when the process of commodifying their desperate loneliness will commence. They are dressed in ball gowns; she is dressed in a T-shirt that reads, “This is What a Feminist Looks Like.”

Why do we love The Bachelor? Unreal suggests that more than the delusion of the contestants or the competition for love, what we love about it is the invisible hand that coerces to people degrade themselves on national television. What Unreal suggests is that watching a group of otherwise normal women fight over a man because someone made them do it is a pastime we won’t easily give up, and that like all power, Rachel’s is morally neutral. But it’s awfully nice to see a woman wielding it.

Evidence That Your Life Is a Fairy Tale, Ranked

by Lisa K. Buchanan

28. You are torn apart by wild horses, rolled down a hill in a barrel of nails, boiled in oil, locked into a heavy trunk and thrown into the sea.

27. You dance to your death in red-hot iron shoes.

26. You melt in the incinerator flames, just out of your lover’s reach.

25. Your mother abandons you to a forest of ravenous wolves.

24. Your stepmother decapitates your brother, then ties his head on with a scarf so you will think it’s your fault when you smack him gently and his head falls off.

23. Your father chops off your hands because you won’t mate with him.

22. You chop off your own hands so your brother won’t want to mate with you.

21. You chop your sister into bits and bury her right eye.

20. Birds peck out your eyes.

19. You’re speechless because you’ve sold your voice.

18. You’re speechless with starvation and acute hypothermia.

17. Your voice is the howling of the wind.

16. Your mother in-law strangles your newborns while you sleep, smears their blood on your lips, and tells your husband you tried to devour them. (The stew does indeed taste funny.)

15. A little gray man forces you to suck his “finger.”

14. You’re adopted, so it’s kind of okay that your dad wants to mate with you.

13. You long to mate with a frolicking weasel.

12. A “finger” prick causes a century-long swoon.

11. A married prince knocks you up while you’re asleep in a tower.

10. You give birth to seven babies, one each day for a week.

9. The prince’s mother is a child-eating ogress.

8. Your prince shits the bed.

7. A severed “finger” lands in your lap.

6. Your lips are as red as blood, your skin is as white as snow, and you’re insufferable.

5. You’ve lobbed the slimy frog against the wall and splattered his guts.

4. Your talking cat growls like Roy Orbison.

3. Your prince has tender paws and a penis with a knot that swells inside you.

2. The mirror on the wall does you shaggy and red-eyed with pointy cuspids.

1. The beast in the bed is you.

Virtual Future Even Stupider Than Actual Present

“The image of a nerd in VR glasses is funny to us now, but just imagine what will happen when Valve releases Half-Life 3 in VR and we all end up sitting for hours, heads encased in black plastic, as we grunt and gesticulate in our desk chairs…. VR is coming. It’s going to change the way we interact with the world. Parents will look back on the days when their kids just wanted to play Angry Birds on the iPad with wistful nostalgia as their kids cocoon themselves into VR-induced comas. The same guffawing Internet users will find that some things — primarily gaming — are better in VR. And the world will change, once again, as VR becomes easier to use and less goofy. We can laugh all we want but right now remember that we’re chortling from the seat of our horse-drawn buggy as the first Model T chuffs down our country lane.”

The Greatest Music Beefs in History

by Brian Barone

Pepin the Short/Charlemagne/Popes v. Gallican Rite: c. 789 AD

The foundational music beef of Western civilization. After Pope Stephen II convinced the Frankish King Pepin the Short to defend the papal stronghold in Rome against the Lombards in 754, a political, military, and spiritual bond was formed between the papacy and the Frankish throne. When Pepin’s son, Charlemagne, took over in 768, he also displayed a penchant for vanquishing Lombards. In 789, Charlemagne issued the Admonitio generalis, which demanded that churches and monasteries in central and northern Europe abandon the prayers and music they’d been using under the “Gallican rite” and replace them with his pal the pope’s favorite music, called “Roman chant.” The eventual hybrid of Gallican and Roman chants would become known as “Gregorian chant.” As a reward, for this and more, on Christmas Day in the year 800, Pope Leo III declared Charlemagne emperor of what we’d later call the Holy Roman Empire.

But it’s hard to forget a tune, even when you want to. This was especially true in a time when the only way to learn or transmit music at all was through memory. So imagine the challenge Charlemagne faced erasing a Gallican chant that churches didn’t feel like changing in the first place. Charlemagne’s biographer, Notker Balbulus (literally, “the stammerer”), reports: “Charlemagne got some experienced chanters from the Pope. Like twelve apostles they were sent from Rome to all provinces north of the Alps. Just as all Greeks and Romans were carping spitefully at the glory of the Franks, these clerics planned to vary their teaching so that neither the unity nor the consonance of the chant would spread in a kingdom and province other than their own. Received with honor, they were sent to the most important cities where each of them taught as badly as he could. But in the course of time Charlemagne unmasked the plot…Pope Leo, informed of this, recalled the chanters and exiled or imprisoned them.”*

A legend began to circulate that God Himself — through a collab between the Holy Spirit in the guise of a dove and a former pope named Gregory — wrote the Gregorian chant and preferred it to all other music. Strict discipline — bullwhips — characterized the lives of the choir boys who studied and performed this music in choirs called scholas. Eventually, the development of a notation system for music helped ensure that nobody would muck around with the pope’s favorite songs. But Charlemagne’s reforms probably never really standardized chanting; some monk has always goofed around with sacred melodies, riffing on old ones and inventing new ones. Music doesn’t like to sit still, even for a king.

Trobar Clus v. Trobar Leu: 12th and 13th Centuries

In this case, the songs of the troubadours and troubatrices, or poet-musicians, of medieval southern France served as both the object and medium of a heated aesthetic debate. In the language of the day, which went by the name Occitan, or langue d’oc, poetry was called trobar, which term gave troubadours their name. Often troubadours and troubatrices were nobles who pursued poetry as a hobby, but some lower-status performers called jongleurs, or minstrels, became troubadours by dint of experience. These artists wrote poems and songs about fin’ amors or the refining and beneficial adoration of an unobtainable beloved. On their saucier cuts, called albas (meaning “sunrise”), troubadours sang of the thrill and danger of getting caught in flagrante delicto as the dawn breaks after a night of love. Because the liaisons described or desired in these songs were often illicit, troubadours and troubatrices relied on a code name, or senhal, to describe the object of their affection.

Another style of troubadour song, the tenso, served as the vehicle for poetry that argued about poetry. Tensos staged a debate between two (real or imagined) troubadours, who might have it out over any number of social, philosophical, or artistic issues. In some cases, the debaters in a tenso were depicted as animals, or even inanimate objects. Often, they’d spar over what kind of poetry is best: obscure, difficult poetry for connoisseurs (trobar clus — “closed” poetry), or clear, accessible poetry for a wider audience (trobar leu — “light” poetry). A favorite argument — in keeping with the meta-ness of all of this — held that trobar leu was the superior approach because its apparent simplicity relied on an art that concealed art, which is necessarily more artful than the art that is known to be art. The clus v. leu quarrel remains unresolved and fiercely debated in Vassar dorm rooms to this day.

Monteverdi v. Artusi: 1600

This disagreement has a backstory which is its own disagreement. In the years between about 1550 and 1570, the Italian scholar Girolamo Mei set out to investigate ancient Greek music (about which still very little is known). Composers of Mei’s day — as well as a leading theorist, Gioseffo Zarlino — liked to claim a classical heritage for the way they wrote music. Mei’s conclusion, that authentic Greek music sounded nothing at all like sixteenth-century music, the so-called ars perfecta, made composers a little tense. On top of that, the ars perfecta musicians were simultaneously under siege from a new approach to vocal music called madrigalism, according to which composers could write any crazy shit they wanted as long as the words of the poem justified it. As one madrigalist wrote: “The notes are the body of music, while the text is the soul and, just as the soul, being nobler than the body, must be followed and imitated by it, so the notes must follow the text and imitate it.” To get a taste, listen to the still wild-sounding music of madrigalist and infamous double murderer Carlo Gesualdo, a composer whose strange music and even stranger life have obsessed more than a few listeners:

Tensions came to a head when Mei befriended Vincenzo Galilei — student of Zarlino and father of Galileo — winning the lutenist and composer over to his way of thinking. Mei and Galilei particularly opposed the ars perfecta practice of polyphony — the intertwining of several simultaneous melodic lines. According to them, such an approach made it impossible to recapture ancient Greek music’s rhetorical power. With so many melodies running around at once, ars perfecta composers were always contradicting themselves. Never mind that polyphony did horrible violence to the structure and clarity of a song’s poem. A crony of Galilei’s, Giulio Caccini, summed up the argument when he called polyphony “that mangler of poetry.”

Galilei broke with Zarlino and started hanging with a crew in Florence (which included Caccini) who began to make practical experiments based on Mei’s scholarship. This bunch of musicians made a splash as part of the entertainment at several weddings of members of the powerful Medici family in the late sixteenth century, especially one in 1589, which featured the debut of a shockingly huge new kind of lute played by the singer Jacopo Peri in a number that featured a ravishing underwater echo effect. In the wake of their success, Peri, Caccini, and other members of the circle proceeded to argue among themselves throughout the next couple decades over who’d actually been the first to invent what’s since been called “the new music.”

It was also at the turn of the seventeenth century that Giovanni Maria Artusi (again, a student of Zarlino) attacked Claudio Monteverdi, a madrigalist who’d eventually adopt the innovations of the Florentines and was thus an ars perfecta-defender’s worst nightmare. He also happened to be a very, very good composer. Cruelly, the ambush came before Monteverdi had even published the madrigals Artusi so despised; Artusi seems to have been one of those people who has trouble with change. Here he hyperventilates over Monteverdi & co.’s musical experiments: “We have reached the point of absurdity, but it is altogether possible that these modern composers will so exert themselves that in time they actually will find a way to turn dissonances into consonances and vice versa.” But the most savage attack was his likening Monteverdi’s music to “a great roar of sound, an absurd confusion, an array of defects.”

Monteverdi fired back in a preface written by his brother and published in a 1607 collection of his music. It accused Artusi of having densely (or willfully) ignored the relationship between music and language in Monteverdi’s work, in which it was “his goal to make the words the mistress of the harmony and not its servant.” He echoes the madrigalist idea that music should imitate its text, and joins with the Florentines in radically declaring words the dominant partner in the coupling of music and poetry. Monteverdi calls the approach the seconda prattica, contrasting it with the older way of writing advocated by Zarlino. The Monteverdi brothers’ response comes down to ridiculing Artusi as a fanboy of a bunch of has-beens. As every hipster knows, that one can sting.

But of course, Monteverdi’s sickest burn would be provided by history itself, which has dubbed him one of the greatest composers of all time. This piece, from the end of his long and varied career, is the most beautiful music I know:

Bach v. Scheibe: 1737

One for the true beef connoisseur, the Bach-Scheibe affair bears several resemblances to the Monteverdi-Artusi spat, most notably that the eventual reputation of a world-historical figure makes the relative nobody who started it look like an utter clown today. Bach had something of a tendency for scrapping with people he didn’t like. Famously, he once went to jail after attempting to duel with a guy he’d called a “nanny-goat bassoon player.” And his disputes with religious leaders, town councils, and deadbeats who owed him money produced letters that are still fun to read. Yet, in the Sheibe showdown, Bach kept mum — or at least that’s the appearance he wanted to cultivate. Like Monteverdi, Bach waged his side of the beef through a surrogate, the rhetorician Johann Abraham Birnbaum.

Birnbaum’s essayistic contributions to the feud were distributed and financed by Bach, so we can be sure that he supported their arguments and probably even helped craft them. The groundwork for the feud was laid in 1729, when Sheibe made an unsuccessful bid to become organist at St. Thomas Church in Leipzig; Bach was on the panel that chose someone else. By 1737, Sheibe was producing a periodical called Der Critische Musicus, in the sixth issue of which he published — only reluctantly, he claimed — a report of the travels and opinions of an “anonymous” and knowledgeable musician. The report told of a “Mr. ______ the most eminent of the Musikanten in ______,” whose flaws (as the correspondent saw them) it outlined in enough detail that any moderately informed reader would have surmised that Bach of Leipzig was its target. As Scheibe would later admit, there was no “anonymous” reporter.

A good deal of the consternation expressed by Bach and Birnbaum following this opening volley centered on the shade thrown by Scheibe’s use of the word “Musikant.” A beautiful and oft-repeated trope in disputes like this: One side uses a word that’s by turns innocent and damning, which goads the other side into obsession with it. We have no exact equivalent in our English, but Bach’s cohort found offense in “Musikant’s” connotation of a mere player-of-notes — a gun-for-hire set of musical fingers — whereas they felt Bach should have been described as a virtuoso in his playing and as a kind of intellectual in his composing. As Birnbaum put it: “The term Musicanten is generally used for those whose principal achievement is a form of mere musical practice…bringing pieces written by others into sound by means of musical instruments. As a matter of fact, not even all the men of this sort, but only the humblest and meanest of them usually bear this name, so there is hardly any difference between Musicanten and beer-fiddlers.” “This is in my opinion equivalent to wishing to pay a special tribute to a thoroughly learned man by calling him the best member of the last class of school boys,” Birnbaum said. “The use of a word that has such an inappropriate meaning, in place of which a far more emphatic one could have been used with little trouble…[indicating] that the author was not really in earnest.”

Scheibe and Birnbaum would go two rounds themselves before others joined the fray, with Scheibe eventually publishing a satirical “letter” supposedly drafted by a thinly-veiled Bach stand-in called “Cornelius.” Instead of playing the mighty organ, as did Bach, Cornelius calls himself “the greatest of all artists on the cittern” — a meager, plucky stringed instrument (think a mandolin or ukelele). The mock letter also takes a shot at Bach’s dependence on Birnbaum: “Though I cannot write against you myself, I will persuade one of my good friends to defend me against you. The learned man who is now writing you this letter according to my indications and ideas will protect me against you, you may be sure.”

Earlier Scheibe had criticized Bach’s music as too polyphonic, too hard, too ornamented, and too dissonant. He called Bach’s pieces “turgid” and in “conflict with Nature,” writing that such complex writing “darken[ed] their beauty by an excess of art.” In response, Birnbaum offered a circular argument defining art as that which “imitate[s] Nature, and, where necessary…aid[s] it,” and therefore claiming that the application of art cannot possibly conflict with nature. Not that Scheibe’s arguments were any more logically sound.

Scheibe would slide into relative obscurity but for his supporting role in Bach biographies; Bach would go on to the greatest musical reputation of all time. The lesson: don’t pick a fight unless you’re sure your opponent won’t become one of the most famous people, ever.

And actually I take back that thing I said before about the most beautiful music I know. This is really it:

Brahms/The Schumanns v. Wagner/Liszt: Middle 19th Century

It was actually more like an all-out turf war, emerging from the power vacuum created by the death of Beethoven. On one side were Clara and Robert Schumann and Johannes Brahms. After Robert hailed a twenty-year old Brahms as “a chosen one” in his magazine, the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, he and Clara adopted Brahms as something of a son. Yet, there has long been speculation about a possible romantic attachment between Brahms (a lifelong bachelor) and Clara, who was fourteen years his senior — especially in the wake of Robert’s death in 1856. On the other side were Franz Liszt and Richard Wagner.

Musically speaking, the beef boiled down to a conflict between “absolute music” (that is, instrumental music ostensibly without extra-musical references) and the merger of music with literature that was mockingly called “the music of the future.” Both sides saw themselves as the inheritors of Beethoven’s throne. But while Brahms continued to write in ‘absolute’ forms like the symphony (his first symphony is still jokingly called “Beethoven’s Tenth” for its affinity with that composer’s style), Liszt and Wagner took off in a more progressive direction inspired by the choral outburst of Beethoven’s Ninth, inventing the ‘tone poem’ and seeking to transform mere opera into the “total artwork” that would embrace all branches of the arts. Wagner — in his classic blowhard style — explained why he and Liszt felt it so necessary to wed music to language: music, he said, “expresses altogether, and in full measure, the emotional content of the elemental human language, independently of our word-language, which has become purely an informational tool. That which, accordingly, remains inexpressible to absolute music is the precise identification of the emotion’s or sensation’s cause, through which they themselves attain greater definition; the necessary continuation and extension of the musical language’s range of expression consists, then, in acquiring also the capacity to indicate with recognizable precision the individual, the particular; and this it acquires only by being wedded to the word-language.”

One of Brahms’ known replies came in response to the takeover of the Robert Schumann-founded Neue Zeitschrift für Musik by a “music of the future” partisan named Franz Brendel, who was responsible for re-christening the Liszt/Wagner faction the “New German School” at a speech during a conference convened to celebrate the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Neue Zeitschrift. In response, Brahms planned to circulate a letter to be signed by a host of eminent German musicians calling-out the Neue Zeitschrift for being in the bag for the progressives. But the letter was intercepted and published by a Berlin newspaper after having gathered only four signatures, a huge embarrassment for Brahms.

This is the rare conflict that ends in victory for all, like the three-way Rolling Stones-Beatles-Beach Boys rivalry of the sixties. Brahms would be remembered as the only symphonist never to write a dud; Clara Schumann and Liszt would go down as two of the greatest pianists to ever live; Robert Schumann remains our finest writer on music and one of the supreme composers; and for some reason crowds still flock to be screamed at in German for five hours wherever a Wagner opera is staged.

*The historical quotes used in this piece can be found in Music in the Western World: A History in Documents, edited by Piero Weiss and Richard Taruskin, and in The New Bach Reader edited by Chrisoph Wolff.