Garbage Removed

Younger readers will not remember this, but there was a period of about three weeks back in 1988 when the man now noted for picking up rubbish on the Boston subway was about to be the next President of the United States of America. Clearly, he was too good for the job.

Movement Conserved

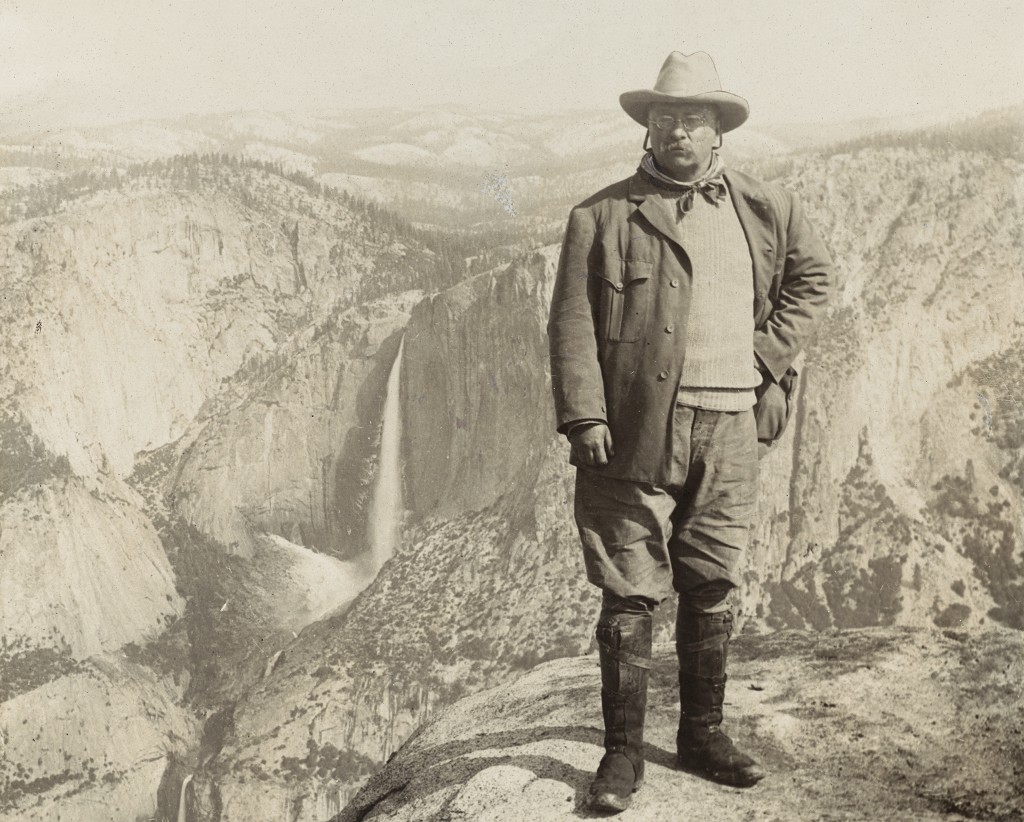

In which the New Yorker (dot com) reminds us that the history of the conservation strain of American environmentalism is not a little racist:

[Madison] Grant’s fellow conservationists supported his racist activism. Roosevelt wrote Grant a letter praising “The Passing of the Great Race,” which appeared as a blurb on later editions, calling it “a capital book; in purpose, in vision, in grasp of the facts our people most need to realize.” Henry Fairfield Osborn, who headed the New York Zoological Society and the board of trustees of the American Museum of Natural History (and, as a member of the U.S. Geological Survey, named the Tyrannosaurus rex and the Velociraptor), wrote a foreword to the book. Osborn argued that “conservation of that race which has given us the true spirit of Americanism is not a matter either of racial pride or of racial prejudice; it is a matter of love of country.”

Even after conservation gradually blended with environmentalism and thus became primarily identified as a liberal cause — because modern conservative orthodoxy no longer allows even entertaining modest impingements to the operation of enterprise, no matter how moral or sensible — it has remained primarily led by well-off whites. As Jedidiah Purdy points out, “a 2014 study found that whites occupied eighty-nine per cent of leadership positions in environmental organizations.” But in 2015 one can be sure that the current principals of the conservation and environmental movement have become sufficiently enlightened to care as much about the kinds of environmental burdens largely borne by poor communities — where, for instance, waste facilities are disproportionately located, according to Purdy — as they do about maintaining the semi-pristine conditions of the wilderness they love to hike through in head-to-toe Patagonia, right?

The Way We Read Then

“I haven’t gone back to Proust since and remember almost nothing of his cast of characters; friends, neighbours, lovers, or the constantshuttle of small events as they unfolded, but I remember being entirely held, and surprised by how held I was…. I could never hope to recreate that reading experience again. The structure of my life would not allow it. But more profoundly, neither would my powers of concentration. My brain has changed, and I do not read like that any more. It felt like a pure luxury, that book. Irrecoverable.”

— This is ostensibly about Proust, but it’s really about something much more poignant.

Diane Coffee, "Soon To Be, Won't To Be"

I am never fully sure of what’s going on but I will cling to any shred of certainty I can somehow convince myself is correct and proclaim it as loudly as possible to pretend to everyone else that I understand how things work. I don’t know why this song appeals, for example, but I am pretty sure that it’s quite good and that if you give it a listen you’ll agree with me, and that’s going to have to be enough. Enjoy.

New York City, August 12, 2015

★★★★★ Sharp light and fresh air came in. The sun was strong enough to be hot; the sidewalk lit faces from below. Facades were neatly defined, and the bricks behind the facades showed all their gradations of color. The clouds seemed to speed up a little when a gaze was fixed on them. The copper dome over luxury condominiums flared or blackened to amplify the passing shadows. Breeze gently flipped the ends of the flags of the United States and H & M. The only flaw with the plan to skip the subway and walk twenty-two blocks was an immense and sticky dog turd at the 23rd Street crossing. Nine, ten years ago this had been the regular walk, Flatiron to Penn Station. The blocks of wholesale goods, with mango vendors on the sidewalk, were hotter than everywhere else. A demolition-waste truck spread dust across Broadway. There were people out on 32nd Street in benches, all along the block, in what was now a traffic-calming lane.

29 Truths About Cancer

by Emy Koopman

1. The truth about cancer is that the word alone scares you. This is why you seldom think about cancer until you have it. Once you do, you will repeat the word in your head, endlessly, until it sinks in. It never does.

You may find yourself thinking, “I have cancer” at the most random moments and in the most random places. Grocery shopping, a festival, a meeting. “I have cancer.” There’s a slight fear you will suddenly blurt it out. You may actually blurt it out when someone who doesn’t know yet asks, “So how are you?”

2. The truth about cancer is that you have to tell people about it. Then they will call and send cards and ask, “Can I do anything?” You may fantasize about asking them to do crazy things. Pray for me, you want to tell the non-religious ones. Bring me some ice cream, you want to tell those who live far away. Buy me a dog and then walk it for me. Go to the washroom for me, take all the swims I cannot take. Or you know what would really help? If you could talk to all these doctors for me. You never actually ask for crazy things, because things are crazy enough as they are.

3. The truth about cancer is that you will appreciate the calls and flowery get well-cards and offers to help, even if that means you won’t have a second to not think about cancer. You might even appreciate the card that tells you that this is an opportunity for spiritual growth. Because one of the things worse than having cancer is having cancer and nobody cares about it.

4. The truth about cancer is that you are very likely to know people who got it before you. This does not prepare you in any way.

5. The truth about cancer is that you really don’t expect to get it before you are fifty. (After you’ve turned fifty, you probably still don’t expect it. But I wouldn’t know, I have twenty years to go before I’m fifty.)

6. The truth about cancer is that you especially don’t expect it if you don’t smoke.

7. The truth about getting cancer when you do not and have never smoked is that it makes you want to start smoking.

8. But the truth about cancer is that as long as you still stand a chance, you are more likely to start bargaining with any omnipotent power around. You will be nicer to people, you will exercise more, you will eat more carrots, you will even eat the overpriced yuppie-superfoods you don’t believe in. Quinoa salad with goji berries, chia seeds, and cacao nibs, yes please.

9. The truth about cancer is it is not a punishment for anything you ate or failed to eat or that you did or did not do. Even smoking.

10. The truth about cancer is that even though you may understand that it’s not a punishment for anything you did or failed to do, you desperately want to hear what caused it — particularly what you did to cause it, since you still assume that you are the master of your own body.

11. The truth about cancer is that even if the doctors can tell you a possible cause, it’s not likely to make you feel better. In my case, it was the human papilloma virus — a virus that most people get, and which most bodies can clean up by themselves. Which brings me back to: What did I do?

12. The truth about cancer is that in most cases, the doctors simply don’t know what caused it. Or why some bodies can’t get rid of the human papilloma virus. Or if my specific type of cervical cancer was caused by the virus after all.

13. The truth about cancer is that since there’s so much that we don’t know, we tend to blame people who get it for behaving in bad and unhealthy ways. (Until we get it ourselves.) As Susan Sontag explains in Illness as Metaphor (1977), we have been defense-mechanism-blaming others for their illnesses since there has been disease. In the sixteenth century, people believed that “the happy man would not get plague.”

14. The truth about cancer is, says Sontag, that it “is interpreted as, basically, a psychological event, and people are encouraged to believe that they get sick because they (unconsciously) want to, and that they can cure themselves by the mobilization of will; that they can choose not to die of the disease.” Sontag wrote Illness as Metaphor while she suffered from breast cancer. She survived, but died many years later of leukemia.

15. The truth about cancer is that if it has a sense of humor, it’s a very black one.

16. The truth about cancer is that once you know you have it, you have the distinct impression of being eaten alive from the inside. “Cancer is a demonic pregnancy,” wrote Sontag, mocking the metaphors that others use for their cancer.

17. The truth about cancer is you may need some metaphors. Sontag could not do without metaphors herself (“Illness is the night-side of life…”). “Demonic pregnancy” is a painfully accurate metaphor for cervical cancer.

18. The truth about being eaten alive from the inside is that it may not hurt at all, not in the beginning at least, not until the doctors start trying to cure you. But without the doctors, there’d eventually be nothing left of you.

19. The truth about cancer is that you will need to find at least one person who cares enough to hold your hand through all of it.

20. The truth about cancer is that you feel the need to joke about it, preferably to the person holding your hand. I joked about the pretty blonde female gynecologist-in-training announcing she would have to basically feel me up.

21. The truth about joking about cancer is that it makes most people without cancer feel uncomfortable.

22. The truth about cancer is that as long as you stand a chance, you can joke about it.

23. The truth about cancer is that you are not in a story, although you may sometimes think you are. You are not in Love Story, Love Life, Turkish Delight or The Fault in Our Stars. Nor are you in some cinematic tragedy with Richard Gere. This means you stand a better chance than you would had you been in a story, since fictional cancer patients tend to be girlfriends who need to die for the protagonists to have their sad, deep, life-altering experience.

24. The truth about cancer is that it increasingly doesn’t have to end with death.

25. The truth about cancer is you’ll be thinking about death all the way through.

26. The truth about cancer is that once you have had it, how can you ever trust your body again?

27. The truth about cancer is that if it does not end with death, it never really ends. You’ll be seeing doctors for years, perhaps for as long as you live. You’ll need them to mediate between you and your body; they will scan your treacherous body over and over to tell you whether it is acting up again.

28. The truth about cancer is that insofar as there is a narrative, the never-ending one with all the doctors and the jokes and the subdued body, is the one to be preferred.

29. But the truth about cancer is that you hardly ever get to hear that truth.

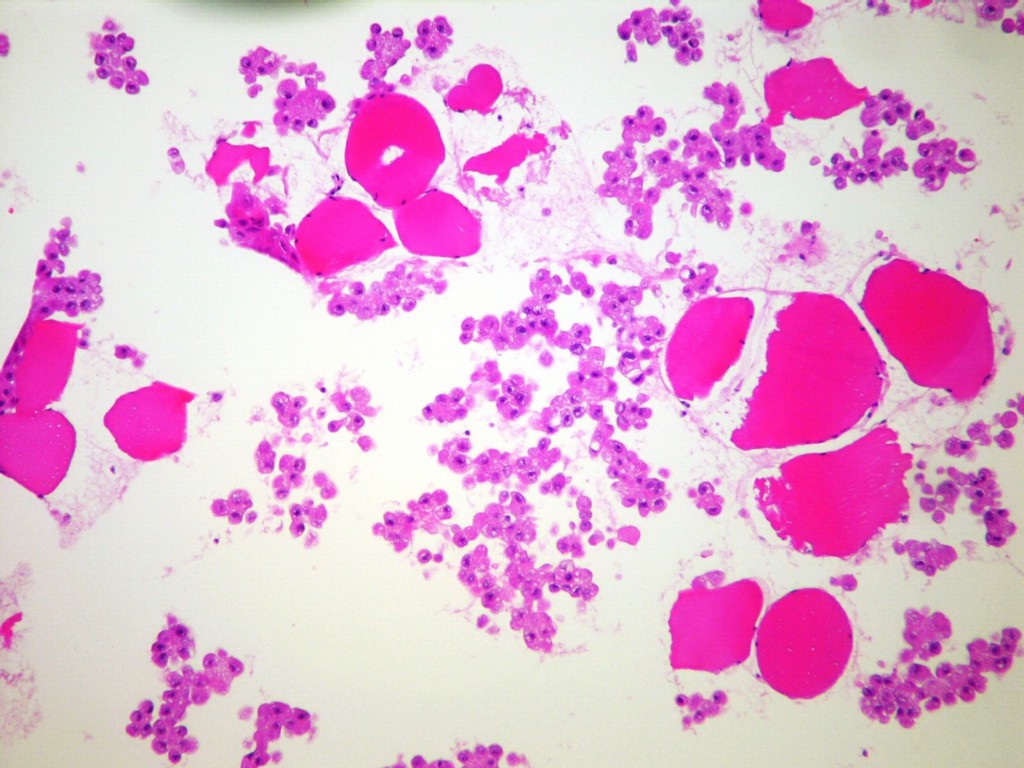

Photo by Yale Rosen

A Poem by Laura Kolbe

by Mark Bibbins, Editor

Vacation Sonnet

for the Go-Go’s

Get me wrong, find it sad: no trunk but that

which glues my arms, two round pegs in sere holes,

not driving, I need a drink. No trip but

the lost goodbye between foot and footing —

oh where does the girl of a hundred lists

take a dry crotch and her crawdaddy charm

on holiday? My luck, it’s everything

but party time. Streets cold as a scraped nail,

television’s a tray of raw chicken,

aquiver, colors who the hell ever

wanted to see — gone the ace days of prime

and purse, how spring was once all over me

like a cheap suit, and now roots nose before toes,

my flush abandoner, a drunk punk on skis.

Laura Kolbe studies medicine in Virginia. Her poetry, criticism, and fiction have appeared or are forthcoming in The New Yorker, The Literary Review, and Alaska Quarterly Review.

You will find more poems here. You may contact the editor at poems@theawl.com.

"I'm going to show you how to clean the ball pit."

by The Awl

I have a theory that the easiest litmus test for privilege is how much contact someone’s had with poop that isn’t their own. Shit: the great social divide. I’m not talking about cleaning up your child’s or pet’s leavings. You love them. It’s different. I’m referring to the clear-cut capitalist exchange of cash for cleaning up. I’ve found that as I rise unsteadily through the social stratosphere, the amount of crap I have to deal with in my jobs has sunk proportionally.

Time Is a Privacy Setting

Twitter starts its latest announcement — “instant and complete access to every historical public Tweet” — with a truly excellent pair of sentences:

Dr. Carl Sagan once famously said, “You have to know the past to understand the present.”

followed by

For brands to most effectively analyze Twitter data in the present, they also need to know what’s happened in the past.

Continuing in the spirit of pale blue dots on which nothing could possibly matter, the feature promises to “solve enterprise business needs with user experiences not previously possible.”

The morning before this post went up, a friend had asked me about deleting her tweets. I’d done so a few months before; plenty of other friends and acquaintances had done so in the last couple years. In each case the impetus was ill-defined and hard to articulate. These were not people who are afraid of anything in particular, really, or worried about horrible things they might have said before becoming suddenly and conveniently enlightened or just paranoid. Mostly these were people who have used Twitter steadily for years. They watched it change in form and function; they watched the people using it adapt to the changes in expected and unexpected ways. They watched it become a machine that manufactures a thousand new contexts a day, urges users to fill them with messages, and moves on as soon things slow down. Imagine explaining to a Twitter user in 2007 what the service would be like in 2009, or to a user then, 2012. Then imagine telling that person what it would be like today. What the hell is Twitter going to be like when they drop the 140-character limit? And how weird will that make our form-obsessed old short messages look? The semi-intentional realities of a platform of millions are only ever obvious in retrospect.

Watch this video and sign this petition if you know that a human life won’t become a donkey or a cat: https://t.co/neRez6ule9

— Marco Rubio (@marcorubio) August 10, 2015

How does your student loan debt make you feel? Tell us in 3 emojis or less.

— Hillary Clinton (@HillaryClinton) August 12, 2015

Maybe people just better understand that this platform is going to change underneath us in ways we won’t be able to easily anticipate? Or the simultaneous inevitability and inconceivability of the changes coming to the various apps and services we use has settled in, and one of the responses these mindful people are having to this is a desire for this small measure of control? When Facebook introduced its timeline-style News Feed, arranging your live events from “Born” to the present day, a number of users assumed old private messages had been exposed — their wall-to-wall public conversations were carried out in such a different context that they couldn’t believe they’d posted them in the open. A few months ago, a friend mentioned a joke I’d forgotten I posted more than a year prior, made about a sporting event I didn’t remember watching. That’s why I deleted my posts: because, looking at the archive, through months of content, not even I could figure out what I was talking about.

Twitter is a massive rolling context experiment, its conversations and subjects and audiences materializing and disintegrating constantly; a single user’s Twitter archive is a series of permanent and public contributions to discussions that have long since ended. A user’s posts referencing the Oscars also reference other users’ posts from the same time, and are experienced first in full transcript. In the archives, however, each speaker is isolated to the point of incoherence.

This is only a mortal risk if you’re in the habit of saying terrible things that you couldn’t defend if challenged, but a scattered trail of thousands of public messages, originally interpreted in the context of a feed but now only available one at a time and lacking context clues beyond a timestamp and maybe a link, still feels like a stupid way to represent yourself to the world. That you might be able to explain them if asked, or reconstruct the context, is irrelevant, because that’s not how they’ll be experienced: they’ll show up in a search, where their decontextualized strangeness, failing to rise to the level of actual inquiry, will nonetheless leave some kind of impression.

Naomi Zeicnher, the editor of Fader, wrote recently about her emerging habits:

After live-tweeting an event, I’ll comb back and trash anything that didn’t meaningfully connect. Sometimes I delete weeks after the fact, while I’m checking in on my profile, thinking about how it comes off in aggregate. Beyond Twitter, I erase text message exchanges to make space on my phone for selfies I’ll delete later too. I untag photos people have taken of me. On weekends, I delete emails for fun.

Here is one conclusion: Time is a privacy setting. Even Facebook knows this! Users can, for example, keep new friends from seeing private posts from the past. On Twitter, there’s a lot less flexibility. You official options are going entirely private or deleting your account; your unofficial option is to delete your tweets.

I archived everything before deleting it all, and now my posts automatically disappear after a week, courtesy of one of the dozens of sites that offers such things. The result is that new posts aren’t saved anywhere anymore, privately or otherwise, unless they’re screencapped or embedded. This is fine but not ideal. I think a reasonable demand — or expecation, given how much of a grind the overall Twitter experience has become as the service has matured, and how evident it’s become that all that funlike work and worklike fun that was much easier to rationalize when both the service and your own experience was expanding in exciting ways was never really going to amount to much — is for the company to treat the age of a users’ posts as one more privacy parameter. I don’t suppose they’re really incentivized to do this. The new search product they’re selling to brands suggests that they’re incentivized not to. But at the very least we can understand this as a problem; as something a better service would offer, and that users of a better internet would take for granted.

Make my dumb bad posts private after a week, a month, or a year. Or at least make the incredibly complicated process of deleting old posts a little bit easier. You’ll probably get more from us if we can still deceive ourselves into thinking it’s ours!