But What If People Actually LIKE "Friends"?

“Rachel makes them happy. Monica makes them happy. Chandler’s annoying intonation makes them happy. The song Smelly Cat makes them happy. Those bits where people who were famous 20 years ago but aren’t any more walk on and everyone claps make them happy. People whooping at kissing makes them happy. The jingly-jangly music they play between scenes — the music that makes you feel as if an awful plague has befallen your ears and brain and you’ll never be rid of it, and it’ll be the last thing you hear, and the only thing you’ll hear in the deathless void of eternity — makes them happy.”

— In a world as awful as this one should we perhaps be less judgmental about whatever small joys people can find in their otherwise bleak and worthless lives? So what if you think “Friends” is the worst kind of brain-numbing garbage, the kind of work that, because it is just slightly better than mediocre, allows people who would be ashamed to celebrate outright mediocrity to abdicate critical responsibility altogether and convince themselves that “no, it’s actually good,” and they are not even pretending to be ironic? With life being an endless journey of suffering that only ends when we are returned to the void can’t we just be okay with anything that brings people a release from agony, however brief and vacuous? This is a serious question, I’m pretty conflicted. “Friends” is SO BAD YOU GUYS. This is not a thing that gets said enough.

Footnotes To Masculinity

Why do self-styled intellectual-type dudes — the grossest, most ineffectual, least appealing specimens of masculinity, the kinds of guys who even in their twenties are walking advertisements for the “low-T” scam the pharmaceutical industry is trying to pull on the flagging libido of the American male — gravitate to David Foster Wallace? (I dunno, MAJOR MISDIRECTED OVERCOMPENSATION?) And how sad is it that they think he will help? God, I could not feel sorrier for you straight ladies, given what you have to put up with these days.

Chvrches, "Never Ending Circles"

I’ve been trying to avoid the onslaught of hype about the new Chvrches album because I am definitively at the point in my life where reading the same story in six different outlets about anything, let alone something I know to be okay, turns me against it even before I can start to sour on my own. Also, the less I am reminded about that fucking “V” in their name the better. And no, telling me they only did it to make the band more Googleable doesn’t help. Why would you think that would help? It’s actually so much worse! It is as stark and concrete a reminder of just how stupid and awful our world is now that you can get. I’m always about to be all, Ugh, you know what, fuck Chvrches, but then there’s the music, and at least for a moment my fury subsides. You, whose fury is nowhere near mine, will have an even easier path to enjoyment, so enjoy.

New York City, August 11, 2015

★★★ Wet windows let in the diminished light of morning. At commuting time, the most recent wave of showers had faded to something just heavy enough to be impossible to ignore. Clouds nipped away the top of the Empire State Building, leaving some different, squared-off landmark. The rain held off at lunchtime, and a cool gust blew. Sun and gray alternated through the afternoon. The waterproof jacket served as proof against the air conditioning. As evening approached, immense piles of gold and white swelled over the Flatiron; on the cross streets, the east was red-orange, the west banded in clear blue. In every direction were tiny airplanes, in sharp silhouette or abundantly illuminated. If you kept an eye down for resudiual flooding in the gutter, conditions were fine for walking. On Union Square, in the dark, someone shot an LED toy skyward, against a background of undulating dirty-purple clouds.

The Lease-to-Own Acquisition Strategy

Today, Vox Media announced (officially!) that NBCUniversal is investing two hundred million dollars in the company, at, according to Peter Kafka, “a pre-money valuation of $850 million…which is another way of saying Vox Media is now worth more than $1 billion.” Congratulations to everyone at Vox! The path to being fully acquired by Comcast is now laid bare.

NBCUniversal is a division of Comcast, which has been one of Vox Media’s most prolific institutional investors. Comcast has invested in Vox multiple funding rounds through various iterations of its venture capital arm: in 2009 (Series B), 2010 (Series C), and 2013 (Series D). Additionally, in May, Vox Media acquired Recode, Kara Swisher and Walt Mossberg’s tech news and events startup, in an all-stock transaction; NBCUniversal News Group had made “strategic investment and partnership” in Recode’s parent company, Revere Digital, a year earlier.

At the time of Recode’s acquisition, we had heard that Comcast Ventures was keen to sell Vox Media to Comcast proper. NBCUniversal’s new investment and partnership with Vox makes for a fairly smooth transition from strategic investment to outright acquisition, as Peter Kafka explains:

Vox Media CEO Jim Bankoff — again, my boss — says that in addition to the NBCUniversal investment, the two companies now have a commercial partnership. That means, among other things, that they will collaborate on digital advertising, will work together on video advertising and video programming, and that you will likely see Vox Media employees more frequently on NBCU-owned networks like CNBC. (Re/code already had and continues to have a news partnership with CNBC).

Hurray for everyone, but especially Jim Bankoff.

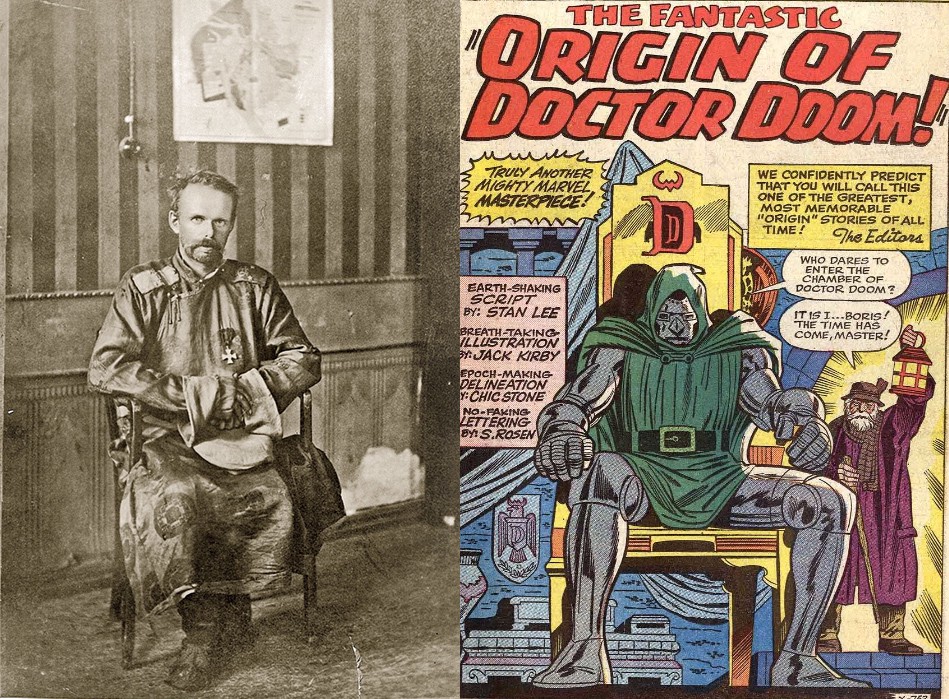

The Forever-Doomed Eastern Europe of Our Imaginations

by Harry Merritt

Comic book films that can’t manage find convincing motivations for their protagonists can often be rescued by matching the heroes against a compelling villain — Loki alone has saved at least two Marvel movies now. But the latest Fantastic Four, which is so spectacularly awful that it’s the first movie to self-reflexively call into question the entire set of structures that have produced The Age of the Comic Book Blockbuster, abandons any possibility of making even Dr. Doom frightening or interesting. In a departure from the comic books, the actor playing the Fantastic Four’s nemesis announced last year that his origins would be rewritten as a Russian hacker named Victor Domashev — stripping Dr. Doom of what makes him a captivating villain.

Dr. Doom represented a new kind of supervillain when Stan Lee and Jack Kirby created him in 1962. Where earlier mad scientist types often possessed limited capabilities and ambitions circumscribed by their name — Calendar Man, Clock King, and Weather Wizard — Dr. Doom was endowed with a brilliant intellect, empowered by an armored suit, and armed with the resources of a small country as the ruler of the European kingdom of Latveria.

Where, exactly, is Latveria? According to Fantastic Four Annual #2, it’s an “isolated kingdom,” which, depending on the panel you at look at, is either located in the Balkans or nestled in “the heart of the Bavarian Alps.” And, though it seems to borrow its name from the real nation of Latvia, Latveria’s mixture of various geographic and cultural features place it in imaginary Eastern Europe, which has a long history in comics — Hergé’s Syldavia, DC’s Kasnia, and, more recently, The Avengers: Age of Ultron’s Sokovia could all share borders with Latveria.

One common element in many versions of imaginary Eastern Europe, including Dr. Doom’s Latveria, is the presence of a German aristocracy. Nowhere did it wield greater power in Eastern Europe than in modern-day Latvia and Estonia, which had been conquered by German crusaders in the thirteenth century. In the centuries that followed — though the lands changed hands between Denmark, Poland, Sweden, and Russia — this Baltic German aristocracy maintained effective control over local affairs. By the turn of the twentieth century, these “Baltic Barons” — a subject of fascination for American journalists — had distinguished themselves repeatedly as loyal generals, scientists, and administrators for the Russian Tsar. But when revolution arrived in Russia in 1905 and 1917, the special position of this elite came under existential threat.

Comic book readers might find Dr. Doom’s army of castle-dwelling robots to be silly, but this synthesis of medievalism and modernism wouldn’t be overly weird in the Baltic region. Facing Bolshevik revolutionaries on the one hand and Latvian and Estonian national activists on the other, the Baltic Barons recruited veteran soldiers from Germany that imagined themselves as medieval crusaders. These soldiers fought in units called

Freikorps, referencing defunct eighteenth-century Prussian military formations. In a fictionalized account of his time with the Freikorps, titled The Outlaws, Ernst von Salomon describes his fellow fighters as “outcasts from the world of bourgeois norms” and “mercenary foot soldiers” (Landsknechte). These men marched past ancient castles carrying flags featuring the Bundschuh (a symbol of Protestant Reformation peasant revolutionaries) and the symbols of the Hansa (a medieval Germanic Baltic Sea trading league), yet went into battle with modern rifles and machine guns, accompanied by armored cars and aircraft.

The Baltic Barons also give us the closest real world analog to Dr. Doom — Roman Nikolai Maximilian von Ungern-Sternberg. Growing up in present-day Estonia, Ungern-Sternberg followed a path taken by many of his kin and entered the Imperial Russian Army. After fighting on various fronts during World War I, Ungern-Sternberg found himself in the tiny garrison town of Dauria, east of Lake Baikal and near the borders of Manchuria and Mongolia, when revolution broke out. Combining a personal brutality with fervent anti-communism and a staunch belief in monarchism and state power, Ungern-Sternberg led his forces into battle against Bolshevik troops in Siberia, then pivoted south into Mongolia.

In February 1921, Ungern-Sternberg captured the Mongolian capital of Urga (today Ulaanbaatar) from the Chinese army and was proclaimed the reincarnation of Ghengis Khan by the Bogda, the spiritual leader of Tibetan Buddhism in Mongolia. Much like Victor von Doom first assumed the identity of Dr. Doom after being clothed in his armor by Himalayan monks, Ungern-Sternberg abandoned his army uniform for a modified version of the Mongolian

deel as he transitioned from military commander to warlord. From his new base in Urga, Ungern-Sternberg dreamed of the restoration of the Qing and Romanov dynasties in China and Russia, respectively.

Ungern-Sternberg’s megalomania and harsh meting of punishment was coupled with unexpected sympathy and understanding for populations traditionally looked down upon by the European elite. Though Ungern-Sternberg was a dedicated anti-Semite, he sought to understand and eventually adopted Buddhist religious ideas and Mongolian cultural traditions. Similarly, Dr. Doom was a patron and protector of Latveria’s Roma, who have long been an “unwanted people” in both real and imaginary Eastern Europe. But when Ungern-Sternberg launched an ill-advised offensive into Siberia in summer 1921, he did not live to fight another day; betrayed by his subordinates and captured by the Red Army, he was tried and executed.

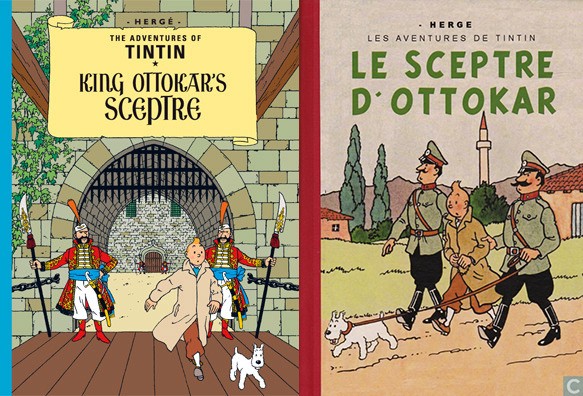

During and immediately following World War II, Eastern Europe’s multi-ethnic, multi-religious, and multi-linguistic borderlands were transformed beyond recognition through population exchange, genocide, and state repression. But even after the Baltic Barons faded from history, other potential avenues for imaginary depictions of Eastern Europe emerged. In a story based on Nazi Germany’s annexation of Austria, Tintin helped save Syldavia from being taken over by its fascist neighbor Borduria in the 1939 comic King Ottokar’s Sceptre; when he returned to Borduria in 1954’s The Calculus Affair, it was depicted as a communist dictatorship ruled by a leader resembling Joseph Stalin.

Once the Cold War began, comic books had more reasons than ever to use Eastern Europe — real and imaginary alike — as a setting. Not only did the Fantastic Four and other Marvel Comics heroes do battle with Soviet-sponsored villains from the sixties onward, but the Fantastic Four’s origins exist in a Cold War context as well. The space flight in which the Fantastic Four gained their superpowers was made hastily, so that “the commies [don’t] beat us to it.” Later, as parts of Eastern Europe fell into ethnic conflict in the nineties, these developments were reflected in the Superman and Batman animated series of that era, with fictional countries such as Kasnia standing in for Milošević’s Yugoslavia.

The collapse of the Eastern Bloc and growth of the European Union have served to further alter the boundaries of Eastern Europe. When Latvians in the nineties flew to Berlin, Paris, or London, many would say that they were travelling “to Europe.” By contrast, today they generally feel themselves to be European. Specifically, Latvians today identify as northern Europeans rather than Eastern Europeans. Other nations have seceded from Eastern Europe as well. Estonia? A Nordic country. Poland? Located in Central Europe.

But Eastern Europe was never truly about geography. In Inventing Eastern Europe*, Larry Wolff argues that Eastern Europe is a concept created in Western Europe during the Enlightenment in order to delineate the boundaries of the civilized world. Eastern Europe, which could neither be considered fully part of the enlightened West nor of the barbarous Orient, served as a liminal space, one both familiar and strange. Whether under absolute monarchies, fascist dictatorships, or communist regimes, Eastern Europe could maintain an exotic quality in the eyes of West Europeans or North Americans.

Thinking back to Fantastic Four’s “reboot” of Dr. Doom’s as a disgruntled Russian hacker — which was largely rescinded in the final cut, restoring Doom’s name and place of origin — such an overhaul makes sense as Eastern Europe’s borders have continually been pushed further eastward, to Russia. Unlike its western neighbors, Russia is still presented as a strange and alien place — recall coverage of the Sochi Olympics, when reporters gleefully shared details of their brushes with Russian backwardness — yet one that we can quickly come to understand because of its simple and unchanging nature.

Given Russia’s resurgent appeal as a source of villainy and setting for intrigue, it may seem striking that Avengers: Age of Ultron returned to a fictional Eastern European nation. But the film’s setting of Sokovia was likely chosen for another reason: Sokovia’s capital served as a backdrop for the film’s climactic battle, leading to its destruction. After the devastation The Avengers visited on Manhattan — and the criticism Man of Steel received for its reckless disregard of fake human life in its cataclysmic final battle in Metropolis — a fictional, quasi-exotic location allowed Ultron to elicit the high stakes excitement of urban annihilation with almost none of the guilt that typically follows when a movie traffics, implicitly or otherwise, in the visual language of disaster established by 9/11

.

The failure of comic book films to build engaging backdrops out of imaginary geography is first and foremost a problem of translation. Despite their lack of multimillion dollar budgets and legions of CGI animators, comic books have long managed to immerse their audiences in fanciful locations that somehow also feel real. But even compared with the half of the film spent in dimly lit compounds, the planet in another dimension visited by characters in Fantastic Four felt dreary and monotonous. The great lengths to which today’s filmmakers behind comic book films go to make their movies gritty and realistic have instead only created worlds that are duller versions of our own.

If Fantastic Four acts as a wakeup call for studios to stop demanding that comic book films be ever more serious, then future filmmakers will hopefully consider returning to the roots of the genre. Rather than insisting that every comic book movie be set in our present-day world, filmmakers can embrace imaginary locations like Latveria, which function as essentially timeless places with vast possibilities for plot and character development.

*Correction: This piece originally mis-titled Larry Wolff’s book. We regret the error.

Destroyer, "Times Square"

What’s that you say? You’d like to hear the standout track from the new Destroyer record? As you wish. Enjoy. [Via]

Let People Know You're Listening And They'll Never Shut Up

“A new study in the journal Marketing Science finds that on one hand, addressing complaints on social media does improve customer relationship with the company. On the flip hand, however, it also increases customers’ expectations to receive help, and makes customers more likely to speak up in the future. That is, responding to complaints has the downside effect of encouraging even more complaints.”

You Too Can Have a Debut Novel Like Mine

by Jane Gayduk

Sitting beside a lager the size of her head and an equally large coffee cup, Alexandra Kleeman spoke slowly and deliberately, describing things in their most biological form — an ode, perhaps, to her academic background in science. Her CV reads like that of a tenured professor, but after nearly a decade of non-stop education, teaching jobs, and loads of accolades, Kleeman is finally ready to unleash something that is strictly her own. Her debut novel, You Too Can Have a Body Like Mine, which arrives on August 25th — and has already received acclaim from The Paris Review, Publishers Weekly and Awl pal Emily Gould — is a story about a nameless character, “A,” who loses herself both literally and figuratively, much to the horror of no one, in a town where people disappear with amazing regularity. Over drinks, we talked about gender dynamics, the role of advertising, and how difficult it is to write something worth reading.

You Too Can Have a Body Like Mine, by Alexandra Kleeman, will be published August 25th. You can buy it wherever capitalism allows you to obtain books:

• Amazon

• iBooks

• Powell’s

You said in a previous profile that “sometimes you go for weeks without writing successfully and you don’t feel like a writer anymore.” How do you get over that slump?

A lot of the time you don’t get over it, so when something comes out, whether it’s an article or a short story or the final novel, I often read it over and I’m like, “Wow, this reads like it was written kind of in order by someone who was just sitting at a computer and thinking.” But there was really so much angst behind it and so much lost time where maybe the other conditions are right. Like, you’re awake and you’re alert and you’re in a good mood and you can write that first part of the scene that you had in mind, but then you hit this impassable wall, where it’s like what I thought should happen next is not good enough to happen next — it doesn’t do everything I hoped it would, now I’ve written negative words, I’ve gone backwards, and I have to figure out how to write the better thing which I couldn’t figure out after thinking about it for weeks. There’s a lot of that. But the best thing that’s developed in the last couple years when I’ve been working is I’ve just experienced that panic contour so many times that I know in the end I will find it. And it might be one day or two days three weeks of trying to work things out, but I will find my way through the narrative problem into something that I think makes the story better — good enough.

How did you to get to this point of relative serenity?

That’s developed over time. Part of it is just trial and error. You’ve found that after struggling it did ultimately result in something. It lets you accept the struggle as just a natural part of the process. And the other thing is I’m just more patient with myself now, because I know also that when you push down on the gas pedal you get this burst of adrenaline and urgency and anxiety. That can help, but more often it’s just a distraction. It’s better to wait and consider and don’t feel bad about things you have to delete because you don’t know how many deleted pages there are in your favorite books.

What’s it like for you as young writer in the current publishing landscape? Is it hard to get your work out there?

I think that it’s hard because MFA programs are expanding so much and they’re producing so many people with degrees and manuscripts in fairy polished condition, so there’s this bottle-necking thing that happens. On the other hand, maybe it’s partially ineffective [in NY], but you’ve got a really great tight-knit literary community and when someone releases a book, you hear about it — it feels like something is happening. It feels exciting and supportive. I don’t know what it means in reality, but when you do get a book out there, I think there’s at least a particular group of readers who are really excited to get at it.

Why did you decide to pursue a PhD on top of extensive schooling and an MFA?

Both my parents are professors and I never really saw people do any other jobs, so I didn’t really know how to want a different kind of job. Once I got into school, I had a lot of interests I felt I could be emotionally committed to — and that I was emotionally committed to. When I was in my last year of college, I made a deal with myself that to do everything I wanted to do I’d have to take two paths, and have to do one first, then the other. So I told myself I’d do the PhD, then before writing my dissertation I’d do an MFA and finish my novel in that time period, then go back to the other thing. But it’s proven a lot harder than I thought to switch — especially because when you write fiction, the more you know, in some way, the more flattened out and narrow your story becomes. You end up writing the thing that you could think of at the beginning, and that’s rarely the best thing you could think of. So I try to go in now thinking of a problem that really moves me and trying to find my less automatic, reflexive solution to it.

In the novel, I noticed a lot of gender dynamics at play. For instance, it seems like most of the men refuse to confront any problems, choosing instead to subvert or run away.

It is based a little on personal experience. I find that men in general are much less conditioned to look self-reflexively at themselves and search for problems that need to be fixed, and I feel like women are trained in the idea of self-improvement and in figuring out the exact ratio of blame that she should accept, or taking on [blame] to save face or something. So I wanted to create a dynamic like that too. I understand, though, that a problem doesn’t exist unless you believe it does, especially for really subjective issues and you could go through life very happily or more happily like that.

Throughout the novel, every time A [the narrator] comes to C [her boyfriend] with a problem, his first instinct is to invalidate everything she feels.

So I’ve talked about this with some people, but is C a good boyfriend or a bad boyfriend? For me, it’s really hard to tell. Obviously he’s wrong for [A] but he is trying to do something. He’s not like a passive drone but maybe the heart of it is that relationships with people are mostly deforming — even though the ideal relationship as we talk about it is, you’re exactly you and they’re exactly them and they respect who you are and you respect who they are. But just naturally by being with someone, what you do is a little bit modified, and modified more and more if you’re with a person who is strongly themselves. So instead of us giving a value to how C is, I just say he’s always working to shape her into another peaceable citizen, like himself, which is what he thinks is right. And for her, that’s a total betrayal of how she relates to the world.

Also, all the men of the Conjoined Eaters Church are described as fleshy, while the women are bone thin. It’s as if the women are constantly wanting of something and all the men are complacent.

To the culture in the Conjoined Eaters Church, maybe no one thrives in it, but men can continue to dwell in it and women are pushed out. It disagrees with their bodies more than it does with the dominant bodies.

And I was going to add about the earlier question: It’s like the difference between Leaving the Atocha Station by Ben Lerner and How Should A Person Be? by Sheila Heti. They’re both about people, approximately the same age, finding their way through life, but in Ben Lerner’s book, all the humor comes from how, when faced with a situation that would make him reconsider who he is, he decides to just fumble and lie his way through it and totally fudge what he actually believes. It’s funny and it’s a different perspective on the challenges that a man of that age could face.

In Sheila Heti, a lot of the challenges are conceptual and they’re thought-based: They’re figuring out how you should be, what kind of decisions you should make as a woman artist of your time and period and age, and reflecting on them almost until it becomes impossible to do them. I think [women are] just trained to think of ourselves differently.

What was the research process like for this novel? Did you look at cult mentalities? Eating disorders?

I didn’t research eating disorders so much as I actually read a lot of things on medieval society and medieval religious society, especially the role of female Christian mystics in the church. They had really, really interesting eating habits that you could say looked like anorexia because it was often this modification of food intake and things like that. But more than being worried about how their body looked, they’re modifying their relationship to the spirit world by eating less. So as they reduce more aesthetically, they’re showing their distance from the cares and pleasures of the world.

That has hints of Buddhism.

Yeah, like a very plain way to live. It was also like eating for meaning rather than eating for all the things that we eat for nowadays: nutrition, pleasure, shaping, sculpting. So I was really interested in that and in creating a cult that thought about food in a similarly spiritual way — but in a way that’s more twisted and twerked into a version of the way we [think of food] as a dominant culture.

I read some great books on the history of food processing and nutrition in America. There’s this great one called Fear of Food that talks about different foods that have become scapegoats for the health problems of the nation and different foods have been the saviors, like I guess yogurt is back now.

I read a lot of reactions to your novel where people warned readers that they may never again want to eat an orange. I actually went to a grocery store halfway through reading the novel with an insatiable craving for oranges.

I was surprised that people reacted that way too. I tried to make oranges strange, but I think they already are strange — not like anything new is being added there. The fact that they’re semi-living beings and have got this whole network of fibers and connectors and vessels actually makes them better food, because they’re living things and you’re a living thing, so they’re commensurable, but I guess I can understand. As a culture, we really like our food passive.

Yeah out of all the things that grossed me out in your novel, oranges did not make the list.

I feel like things are weirder in our food production chain than I can even make up. I wouldn’t invent pink slime, but pink slime exists: It’s a non-fictional entity. Like that stuff grosses me out so much I couldn’t make it up.

Food, advertisements and commercials are a huge topic in your novel. What role do you think advertising has come to play in our culture?

I’ve come at advertising after a period of having boycotted television for several years; up until 2011 or something I never had a TV in my house. And when I came at advertisements from not having seen them for a while, they seemed extra surreal to me. They’re these little pockets of weirdness in a programming world that’s otherwise pretty literal all the time — pretty realistic — but then suddenly you get these characters who so fervently believe in the power of a certain product, they’re so fervently wanting to fix this one problem. You have these weird extreme emotions like jealousies and affections for things that no normal person would, so I find them really interesting and almost beautiful in that way, like surrealist films. You can feel how much money goes into commercials by how swiftly they act on your mind. And they’ve got like a hypnotic quality to the way they present their products. I can feel myself taking on a desire for that thing, or at least like feeling the desire they want me to feel, when I see a beautifully done eye, or make up, or the softness of some cotton fabric bouncing up and down. You want it on this bodily level even though mentally you don’t need that thing at all and you’re a little bit confused about why you’re watching it. So it’s an amazing art form when you look at it.

“Art form” is an interesting way to think of it.

It’s not art, but it borrows a lot from art, and I think the level on which it affects you emotionally is often a similar plane to how you feel drawn in by a sculpture and the texture of a painting or color. They’re making use of all the emotional, sensory things to get you involved. It’s also — in the time in which we live now, we have ideas about the circumstances art should be made in and how it should be captured, packaged and presented, and part of the work of those production mechanisms is to separate art from advertising and popular film. But in the days of Michelangelo or whatever, art could be bankrolled by large organizations for a public or unifying purpose, so I think that Blockbuster movies could be like the cathedrals of now. And you don’t have to love them, but you have to respect how much energy has gone into trying to make them immediately appealing to you.