New York City, August 16, 2015

★★★ A dirty haze was rising in the west at dawn. A little squad of clouds cut off the direct sun briefly and then departed. More came in after, their contours dramatic but unreal through the blur of haze, the light around them tinted oddly. Out in the thick heat, an SUV sat at the curb with its windows down, blasting music too loudly for its speakers as the driver bustled around doing something outside it. A pigeon waded into a puddle up to the feathered part of its legs, bent its head, and drank. Some of the clouds, moving overhead in the afternoon, looked capable of rain. The blacktop by the Tavern on the Green was intolerable, making escape to the Park momentarily worse before it got better. A saxophonist played what was, on attentive listening, “Call Me,” with a 30-foot radius around him empty of anyone not in the process of going by. Two kids whirred along on free-range go-karts, checkered pennants flying from the rear. The doubled shade of the clouds and trees had an effect; a cool breeze rolled along the dusty ground. A little burst of raindrops fell. Later, another little spray would streak the apartment windows, followed by returning sun and a confused blue mist on the river. The air in the Times Square subway station was so hot it hurt the eyes. As the N train rose up into Queens, the sun was finding thickness in the battered markings on roadway ramps. Light traced a swayed roofline nearby and the top edge of a cloud mass high over Manhattan. After dinner, the night clouds appeared to be, through some accident of the light pollution, plain white.

Notes on 21st-Century Mystic Carly Rae Jepsen

by Jia Tolentino

The first time we were anything is the last time that anything was possible. We start off life totipotent: one cell, absolute potential, ready to knit itself out towards infinity. Totipotency is a state that lasts about four days and feels as distant as some other, wilder precedents: the fish, the amphibians, the speechless hominids staring at the sun. Every Sunday night proves it: You’ll never get this back. Cells themselves can regain totipotency1, but the means by which they do so remain occult. We — that one cell turned into a degrading thirty-seven trillion — sense our lost totipotency only in the rarest of flashes, and I think, only at the very first second we feel a new kind of love.

Carly Rae Jepsen is a pop artist zeroed in on love’s totipotency: the glance, the kaleidoscope-confetti-spinning instant, the first bit of nothing that contains it all. This is audible and immediate in her voice, whose definitive quality is a childlike ardency inflected with coyness; she sings like her smile is bursting, like there are stars imploding in her eyes. Her music, strictly and deliberately generic, transcends its structure through this sonic technicolor hurry, this ecstatic sense of the possible, untethered from the way anything works.

And so Carly Rae’s music is tied up with an adolescent but ageless question: What’s more compelling — the falling or the love? Infatuation is an unrealized glimpse of future possible, and how you are as a person depends greatly on whether this vision supersedes, creates, or gets eclipsed by the actual possible. Carly Rae, anyway, is not interested in actual possible. She sidesteps the conundrum, and in a very particular way. The nameless, sparkling tension in her music comes from two parallel but opposite forces: Her substance regresses back to an impossible purity of emotional intention, while her form progresses towards an emotional climax that, necessarily imaginary, can never come. Carly Rae wants love; she wants nothing more than to want it — as in, she literally will not move past that point.

And so Carly Rae becomes somewhat of an unlikely mystic. In Decreation, the poet Anne Carson wrote about art without a personal center — a hole in the middle, left open for God. Carly Rae has resuscitated this idea, shot it through with molten sugar and planted it in genre. She’s displaced herself from the center of the pop album, a self-centered form, designating love — or E • MO • TION, the album’s title — as her god.

Decreation’s title comes from religious philosopher Simone Weil’s idea of self-erasure. Carson quotes her: “If only I could see a landscape as it is when I am not there.” That’s the project that occupies much of E • MO • TION, its diffuse and unbearable babyish exaltation the sound of a highly pop martyrdom. The love of Carly Rae’s sonic imagination is distinctly spiritual: directed with unimaginable force at some distant object, further distinguished by having no subjectivity at all. Piece by piece, she insulates her subject matter against self-pollution, building a cathedral out of crystal and neon and smoke.

She stays, for the most part, absent, and in doing so becomes wildly present. The productive paradox of the mystic is in here: You can’t have erasure without a self to erase. When you raze your own presence, you are empowered by what goes up in place of it; the mystic becomes stronger in a degree that corresponds to self-extinguishment. The thirteenth-century mystic Marguerite Porete, eventually killed as a heretic for claiming to be able to access the divine directly, cried out in her writing to be an “annihilated soul.” Six centuries later, Weil wrote, “But when I am in any place I disturb the silence of heaven with the beating of my heart.”

Decreation draws heavily on both Porete and Weil, and for the writer, the paradox gets sharper. “Withness” was the problem, wrote Carson: “I cannot go towards God in love without bringing myself along.” The teller can’t disappear from what she is telling, and what’s more, a writer’s vocation renders this project disingenuous from the start.

For the pop star, disappearance is even less fundamentally possible, and Carly Rae — productively — is not always content to stay on the outside. It’s in the friction between her self-effacing vacancy and desperate presence that she achieves something like genius. The synth-blistered, drug-distilled, hyper-real sax howl that opens the album into “Run Away With Me” opens up into a tripleted club beat that, by the chorus, has Carly Rae pounding her fists on the walls of her cathedral she built to protect what she’s looking for. Baby, she sobs, take me to the feeling. It’s the best pop song of the year.

Carly Rae has always been in pursuit of interpersonal totipotency, the bubblegum/impossible/first kind of love. She is, really, the queen of it: Her breakout track, “Call Me Maybe,” situated pure heart-eyes potential in a single transaction that’s almost sure to go nowhere but is, at that moment — and here’s what those skipped-beat synth riffs will convince you — capable of leading to an eternity of bliss. Hey, I just met you/ and this is crazy. The text-message lyrics are fitting; infatuation is the dumbest, most colloquial thing in the world.

Because of this focus, Carly Rae is often criticized as being juvenile — isn’t she actually almost thirty, people will say, accurately — or lowest common denominator, for doing things like placing an entire hit chorus on the stairway-to-nowhere of I really, really, really, really, really, really like you. She’s also criticized for being, I guess, unsophisticated, but a few times through E • MO • TION and it’s obvious she is in control of the genre, rather than the opposite. Her music is often read as unintentionally blank when it seems to me to be obviously deliberately so, and much of the basis for all this confusion, I think, is the fact that she appears somewhat narrative-less: At a time when music criticism is both overworked (hello) and heavily reliant on intentional fallacy, pop stars are expected to provide either biographical or signatory hooks on which to hang a reading (or ideally, like Taylor Swift and Beyonce, both at the same time). Carly Rae was on Canadian Idol, released a debut album, released “Call Me Maybe,” another album, and now she’s here. Her hooks are only, and abundantly, musical. Outside that, she has her thicket of bangs, and fin.

So, though E • MO • TION should by all rights be enormous, Carly Rae seems paired with this basic confusion: Why isn’t she clearer about how we’re supposed to read her, why isn’t she bigger, why don’t we have more to work with here, people will say. Even people who love the music could wonder: How are the songs so direct and the artist so absent, the licks so obvious and the image so dissipated in smoke? The listener, I think — like the critic — wants to be the intermediary: to be pulled into the equation between the artist and what the artist seeks. But Carly Rae, like Marguerite Porete (who, again, was burned at the stake for it) seems to be after direct communion. Her willingness to be directly possessed by emotion — to regress, away from narrative, away from audience, back to that original point — reminds me of Porete’s idea of the soul stripped naked by divine presence. A soul:

to whom one can teach nothing

from whom one can take nothing away

to whom one can give nothing

and who has no will at all.

To be an original in this respect does not necessitate that Carly Rae be original in any other whatsoever. Melodically, she’s right on top of other people’s territory for much of the album. “Making the Most of the Night,” co-written by Sia, sounds like her; “Warm Blood” sounds like Lykke Li on moon rocks; “All That” perhaps should have been Jessie Ware; “LA Hallucinations” (whose first line is incredible: I remember being naked/ We were/ Two freaks just fresh to LA) has a tack-to-delectability ratio and hilariously declamatory chorus that conjures Britney Spears in “Born To Make You Happy”; the great bonus track “I Didn’t Just Come Here to Dance” sounds like what Taylor Swift’s next album will sound like if she keeps dating Calvin Harris. Vocally, Carly Rae gestures towards Ariana Grande on “Boy Problems” — whose first hook is so far up and forward in the nose that I sneezed in sympathy — and, with her roughed-up alto pulled up into little-girl coquetry, she sounds like Selena Gomez on every other song.

But “Run Away With Me” is the song that only Carly Rae could do, the song that epitomizes and matches and clarifies her artistic center. Listen to it again, right now. Robyn could get the closest — Robyn can do pure longing — but it would be more complicated: Robyn is as sad as she is buoyant, always knowing, always wrecked. Katy Perry could do it, too, but then it would be slick, anthemic, the finish line of the race rather than the gun that begins it. Taylor Swift could inhabit and electrify the sheer direct pull of the song, the big Swedish chorus. But it’s the defining feature of Taylor Swift: She is never, ever, ever going to be de-centered.

So, Carly Rae is almost everyone, and in the process she becomes no one — just not in the way that people might think. She’s not derivative but absorptive. E • MO • TION burns three decades of pop down to a few heartstrings and plays them from a home base of pure need. And in the playing, Carly Rae becomes invisible, the Casper of pop music, this album her Lazarus machine. There’s her resolution to that paradox. If only I could see a landscape as it is when I am not there. One way to do it is to be a ghost.

I feel sort of a reverse recognition when I listen to Carly Rae. I have never been good at valuing infatuation or falling helplessly to my needs, but I would like to be. Love is steady even when it’s enveloping; it’s an endpoint that’s always felt un-mysterious and immediate to me. The great, stupid, fascinating mystery is that vectored positioning — that ambient hunger, that sense of possibility, the deliberately thoughtless worship of love before it complicates or decays. Wouldn’t it be wonderful to stay there, hovering at the unreal beginning, under a spell of violent self-enchantment? Tearing your eyes out and replacing them with stars?

Gimme love, goes one of her choruses. Gimme love, gimme love, gimme love, gimme love, gimme touch/ Cause I want what I want/ Do you think I want too much? That’s Carly Rae for you. The world, as they say, is a vampire; by sheer force of wanting, Carly Rae outpaces the world. On the chorus of “LA Hallucinations,” there’s a line: There’s a little black hole in my golden cup/ So you pour and I’ll say stop. It’s a neat and perfect recompression of her genre, whose broadly painted cravings are just accessories to infatuation; it’s a sixteen-word explanation of her endlessly desiring ethos, and of endlessly desiring, you and me.

1. Well, pluripotency, but close enough.

The Color of Disruption

by Rebecca Huval

Startup offices tend to look the same; they save the “innovation” for the apps. Exposed pipes or concrete pillars provide an industrial flourish, so web developers can romanticize their work as hard labor. White walls function as a blank page, just begging to have buzzwords plastered upon them. Meanwhile, natural pinewood speaks of cleanliness, friendliness, neutrality, banality, and humanity. Invariably, an accent color disrupts the dull, neutral canvas in the form of a bright couch, a stiff designer chair, a throw pillow or two, or a jarring rug. Often, that color is chartreuse.

The midway point between green and yellow, chartreuse might appear as subdued as pear and pistachio or as zesty as lime. It is the answer to that contested question: Are tennis balls yellow or green? They are neither and both; they are chartreuse. Some shades are more natural than others; the unnatural hues have a sharp yellow zing, while the mellower tones show off refinement. But why chartreuse, always?

Branding. Chartreuse “screams lively or quirky,” Michelle Richter, senior designer at O+A, an interior design studio that has decorated for the likes of Uber, Yelp and Cisco, told me. Tech workers use zany hues because “uniqueness is valued” in the industry, Leatrice Eiseman, director of the Pantone Color Institute, says. “It’s a real attention-getter, and that’s what you need when you’re starting out. It truly is an unignorable color. There are other colors that you hardly see, but not in your chartreuse range.”

Bandwagon chartreuse offices and interiors around the world include: Meltwater, squaretrade, Microsoft Startup Labs, Airbnb, Cisco, The One Workspace Headquarters in Santa Clara, the AT&T; Foundry in Palo Alto, the publishers of the Myers-Briggs Personality Assessment in Sunnyvale, Zendesk everywhere, chat software producers LivePerson NYC, half of these “inspirational collaborative workspaces” for Generation Y, ad agency 22squared in Atlanta (pictured), this chartreuse abuse at tech company Koninklijke Philips in Somerset, this so-cool-it’s-serious coworking space Kleverdog in Los Angeles, Microsoft in Vienna, an alien-themed collaborative workspace in Spain, and Google everywhere, but especially this shire of chartreuse inside Google Dublin, among others.

Chartreuse balances opposing moods. Green is universally adored. Consistently voted second place in favorite-color surveys, green signifies “calming” and “peaceful,” and connotes nature and ecology across cultures. Tech companies can safely use the color for interior decorating and branding to win everyone over, with very few exceptions. (In China, a green hat symbolizes that a man’s wife is cheating on him.) Yellow, on the other hand, can be a risk: It is the world’s least favorite color. Although it can radiate happiness and extroversion, it can also be diseased, jaundiced, insane, like Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s short story, “The Yellow Wallpaper,” about a woman driven mad by the “sickly sulphur tint” of her wall decoration. It’s the color of cowardice, like the yellow-bellied wimps of old Westerns. Interior designers want to add vibrancy to a startup’s palette, but they tread gingerly down yellow roads, brick or otherwise.

Together though, yellow and green is a powerful combination. “Chartreuse is the most exciting of all greens,” Eiseman says. “Yellow denotes friendliness and good cheer. You’re adding a bit of sunshine, if you will.”

Chartreuse gets its name from a liqueur, which in turn was named after the Grand Chartreuse monastery, tucked in a valley in southeastern France. In the early seventeenth century, Carthusian monks developed the pale apple-green drink using a secret recipe gifted to them by one of King Henri IV’s marshals, a blend of a hundred and thirty herbs, roots, seeds, and flowers. It was supposed to produce an “Elixir of Long Life,” and in one sense, it has provided them extreme longevity: Carthusian monks have made 11 million euros off of Chartreuse, allowing them to remain completely cloistered in the Grande Chartreuse monastery. “The Carthusians are the most contemplative and withdrawn religious order in the Catholic Church,” according to the Independent. “They live an entirely enclosed existence.” The order maintains a non-disclosure agreement on the recipe, known to only two monks. If they were in Silicon Valley, the Carthusians’ resume might read: “Crushing it — and herbs — since 1605.”

The term wasn’t used to describe a color in English until the late nineteenth century, when the British fashion-and-literary magazine The Domestic Monthly described a “delicate, pale green, with a yellowish tinge, entitled ‘Chartreuse’” as “a rival to the renewed apple green” which “is lovely in the large feather fans.” (Keep that in mind the next time you buy a large feather fan.) The new pigment bedazzled velvet hats and Chantilly cloaks, until it came to mark a certain fin de siècle aloofness; the phrase “greenery-yallery,” meaning green-yellow, became a putdown for the hue as well as the British Victorian intelligentsia and their affectations. Even then, chartreuse was regarded as a difficult green to match. In 1905, Dry Goods Reporter noted, under the subheading “Choosing an Easter Hat,” that, “Chartreuse greens are among the colors hardest of all to combine artistically, and yet with the new popular bluet are charming.”

In the nineteen fifties, chartreuse arrived in modern interiors, which flashed bright shades in the optimistic spirit of the post-war boom. Yellow-green entered the realm of kitchen cabinets and sofas in the US, where it married natural avocado tones with futuristic style, indicating a rosy outlook on the nation’s prosperity. With more money in their pockets, middle-class shoppers distinguished themselves through the uniqueness of their consumer choices. In the 1956 issue of Billboard, a chartreuse jukebox was advertised “as colorful as its colorful music.” Chartreuse was for consumers with personality, who danced next to their in-home musical machines — not unlike the dose of charisma and futurism startups use it for today. The tartness of the color ratcheted up in the sixties, when it entranced viewers on psychedelic posters and tapestries, and was deployed to make department-store products groovier, from dresses and purses to plastic phones and microwaves. Finally, in the seventies, it rooted itself in ecological propaganda. “But by the eighties, everyone had gotten tired of yellow-greens,” Eiseman says. This trend is visible in Pantone’s “The 20th Century in Color” graphic (from the book of the same name, co-authored by Eiseman): Chartreuse raged through the fifties to the seventies, but its popularity went dormant in the eighties and nineties.

Then the first dot-com boom vomited primary colors onto every interior surface. Leslie Bamburg, interior designer of Lab Experiment, worked in Bay Area startups in the late nineties and saw it firsthand. “Companies like Google were just getting big and making their splash with these crazy offices that were all about whimsical fun, like treating work as a place to play rather than a place to work,” she says. “It was all primary colors, bold and vivid, and it felt like a playground.”

In the early aughts, chartreuse regained its footing in the home once interior designers saw it with fresh eyes after two decades of letting it rest. First, it popped up in smaller, boutique home accessories lines. Over time, big box stores such as IKEA and CB2 picked up on the trend in their furnishings for home offices. “I think it was around 2010 when CB2 had a huge amount of offerings in chartreuse,” Bamburg later wrote to me in an email. In the houses of the sixties and seventies, chartreuse was paired with brown and orange; accompanying gray and black in recent years, it felt like a whole new color.

Tech companies, which began looking to home design to evolve their interiors, matured their color palette with the aid of chartreuse. “I’ve noticed a move toward sophistication,” Richter says. “It’s less about having the loudest and proudest color; it’s more of a blend and a layering of palettes. Startups are growing into their roots.” As an accent color, the overly exploited chartreuse is the ideal compromise, with the vivacity of a primary color, but the urbanity of a more complexly blended shade. “Employers want their employees to feel excited, energized and creative, and chartreuse encourages those things,” Bamburg says.

As a home interior designer who has also worked in office design, Bamburg noticed that the tint, which creeped from homes into offices, shifted back home again, like a green ouroboros. This is the logical outcome of today’s employers wanting workers to practically live in the office: Startups create workspaces that look and feel like home, so young employees who spend most of their time at work acquire their first interior design influences at the office. “The differences between a twenty-something’s apartment and their office is becoming smaller and smaller. The things popular in the residential design world have been influenced by the tech world, and the things in the tech world are influenced by the home. It reinforces the office’s home-away-from-home quality.” (Is that Mark Zuckerberg, studying Chinese with a tutor in his in-home office, painted in a pale chartreuse? Yes it is.) “The new thing is to make these places feel comfortable and welcoming,” Bamburg says. “That helps the bottom line if employees feel like they’re at home and they never want to leave. I see more comfortable spaces like living rooms, basically, in offices.”

The result is that chartreuse has become “the new bright orange,” Bamburg says. “Ten or fifteen years ago, bright orange was the hot color of the moment — it was vivid and exciting, but because it got so overused, it fell out of favor. Chartreuse is in that camp now. It’s used everywhere, but I can also see it becoming so overused that people back away just in reaction to it.” But if the ubiquity of chartreuse comes to an an end, it’s only a temporary one. “Most colors, especially bright colors, have their moments in history and come and go and come back again decades later,” Bamburg says.

Eiseman believes the future of chartreuse can be found in the Chartreuse Mountains as easily as in her own garden in Bainbridge Island, near Seattle. “Chartreuse combines so well with other colors. Looking at bright yellow-green, you can see it as a background to other flowers or a foreground. You can’t look at it and think, boy, mother nature made a boo boo. You look at it in the context of nature. Some people say, ‘Oh, you should never do yellow-green with purple’ because that’s their personal take on it. But you see hydrangeas in front of chartreuse you go: ‘Oh my god, it’s gorgeous.’ If we look at nature and keep our minds open to color combinations, it can be quite incredible.”

Photo of Chartreuse by Dominic Lockyer; retro kitchen image via retro renovation; and photo of Koninklijke Philips office by Interior Design

JoJo's Back, Baby

by Rachel Stone

JoJo’s first single “Leave (Get Out)” shot to the top of the 2004 Billboard charts and the CD drives of America’s minivans when she was only 13; her eponymous first album went platinum. Two years later, she followed up with “Too Little Too Late,” and a sophomore album called The High Road.

And then she went MIA for a maddening nine years.

In what I had previously assumed was either a D’Angelo hype-building technique or just the Absolute Worst Puberty Ever, JoJo’s absence was caused by legal issues with her record label. They effectively kept her new music hostage, the artist unable to release anything but mixtapes and YouTube covers until she finagled a contract with Atlantic Records in 2014.

And now, she’s back — dropping three songs this week, and people are amped. Who needs a refresher on her most important work?

Drones Bad For Bears

“Bears show signs of stress when drones are flown near them, according to a new study.”

23 Things You'll Only Understand If You Join A Union

“We are all replaceable. We work in an industry in which there is a greater supply of good writers than there are well-paying writing jobs. Ask the thousands of talented and experienced newspaper reporters laid off in the past decade how non-replaceable they turned out to be. Even the most skilled and gifted writer of astounding prose is replaceable, if business reasons call for it. Listicle composers, even more so.”

O R C A S, "Into The Night"

Those of us who were there for ’90s the first time around know better than to be enthusiastic about having to do them all over again as digital downloads, but if you who were too young to fully experience the Clintons and “Twin Peaks” and clear beverages during their original run I can only say “sorry,” “good luck,” and also, “Maybe this time let’s skip the nu metal thing.” Enjoy.

New York City, August 13, 2015

★★★★★ Bright and shapely clouds, smooth in general shape but a little ragged in the details, stood in not quite formation against a clear light blue sky. Their distribution was irregular but complete, so that blue and white were fully and multiply represented in every gap between buildings. The sweltering stale atmosphere in the subway had nothing to do with the topside air. Up on the new, high office roof — the view easily spanning from the Hudson to the East River and the abundance of of water towers in between — the sun was strong, the parapet hot to the touch. Plants stirred in some rooftop gardens and stood still in others. The street shade deepened while the higher floors of buildings still shone. A family of three generations swayed and sang along with a street trumpeter playing “When the Saints Go Marching In” on his silver horn. In the tranquil night, the smell of growing things entered the cab window on the approach to the Park. The sky was discolored by haze and light but cloudless now. Prolonged gazing up into it gradually revealed faint stars, elusive to the eye but fixed in their places, and one very late distant passing airplane, and then — possibly, fleetingly, in the floating uncertain depths of vision, a quick fingernail streak that might have been the incineration of a Perseid.

I Watched the Bear Cam for Eight Hours Straight

by Shane Ferro

July 25, 2015

9:07 AM: I’ve committed to watching the bear cam for eight hours.

The bear cam is a National Parks Service-run twenty-hour live feed of one tiny section of Alaska’s Brooks River, where brown bears often are found hunting for salmon in the summer. The river is in Katmai National Park, which is nearly three hundred miles southwest of Anchorage, and pretty much only accessible by boat or plane. Or it was, before the bear cam.

9:08 AM: I never noticed there’s a still image that says “Live Cam” before you press play on the cam. This indicates that you are about to watch nature porn.

The camera moves occasionally, but inconsistently. It is mounted on the shore, and is usually trained slightly upriver on what is known as Brooks Falls, a waterfall that stretches across the river and is maybe five to ten feet high. Most of the time the bear cam’s view encompasses a maybe two-hundred-and-fifty-square-foot area that contains some the most popular bear fishing spots on the river. It looks like this:

9:09 AM: Two bears, at the far end of the falls. (Update: Just one bear at the end of the falls. There was a rock that looked like a bear’s butt.) I like watching the falls without bears, though. It’s very soothing. One of the bears comes toward the camera, fighting through the rougher part of the river to get to shore. It succeeds, then wanders off.

Two of the best fishing spots are at the section of the falls closest to the camera — the lip, at the top of the falls, and the jacuzzi below it (so named by the National Parks Service), where water rushing off the lip creates a large area of foamy water. The far end of the falls is shallower and is known as the “far pool.” According to the NPS, bears that fish at the far end are often less tolerant of people, and stay away from the camera. As far as I can tell there is a camp and a park ranger station near where the camera is positioned.

Here’s what it looks like when bears are fishing on the lip, the jacuzzi, and the far pool all at once:

Sometimes — and it’s unclear whether this is done automatically based on movement or by hand — the camera will swivel downriver, where females, younger bears, and smaller or less aggressive male bears will fish. The camera also will sometimes zoom in on a bear, which makes me think it is done manually.

9:13 AM: Another bear has appeared at the top of the falls (although it is perhaps the bear who went to shore?)

9:16 AM: The bear caught a fish!

9:20 AM: The cam is black and white, which must mean that it’s still nighttime?

9:23 AM: I visited the National Park Service’s website, where there is more information on the bear cam. I learned that July is the best month to spot bears fishing for salmon (I’ve just made it, as it is currently the last week in July), although they are present from mid-spring to late summer. Brown bears are the only kinds of bears in Katmai National Park, although there was once a single sighting of a black bear. There is also an ebook specifically written on the bears of Katmai National Park. I have obviously just downloaded it.

9:31 AM: My coffee is finally ready. I’ve decided it would be festive to drink it out of my Teddy Roosevelt mug, as he is known for doubling the number of national parks in the system while he was president. (He became a conservationist after going on a buffalo hunting trip to the badlands, just as the species was about to go extinct.) Please do not ask me why I have a mug with Teddy Roosevelt on it.

9:41 AM: While I was writing about Teddy Roosevelt, the bear cam froze.

9:47 AM: According to Google, sunrise in Katmai is at 5:52 AM, which is in five minutes. I wonder when the camera changes from black and white to color.

9:56 AM: Sunrise has come and gone. Brown bears don’t care. One of the bears is dunking his head in the frothy water at the bottom of the falls.

10:14 AM: Four bears now! The real fishing day has begun. Still in black and white.

10:22 AM: And we’ve got color!

10:45 AM: At the top of the falls, one of the bears is going after the salmon. I have a feeling that things are about to get exciting; the bear slaps the water several times after failing to catch a fish. Pretty sure the bear is trying to trap the salmon between a rock and its paw, but in my mind he is throwing a temper tantrum. This is clearly the best fishing spot.

11:00 AM: This bear still hasn’t caught any fish. A bear at the bottom of the falls, though, is munching on something.

11:07 AM: The constant running water is very soothing, but that will make it hard not to fall asleep. The bear missed a fish again.

11:08 AM: Frozen, again.

11:18 AM: I’ve had a lot of technology trouble, but this bear is still at it, having a mild temper tantrum over not catching any salmon.

11:27 AM: MAJOR UPDATE: I ditched the iPad in favor of a computer, which I then ditched for the Roku box. All of them are frozen. I’m ready to say that this is a problem at the National Park Service level, not with my devices. Also, I’ve realized just how many devices I have in my apartment that allow me to stream YouTube.

11:34 AM: I am taking this opportunity to read the Washington Post’s profile of the painter Alex Katz. The beauty of the internet is that when one thing goes down there is always a replacement.

11:49 AM: In the continuing absence of the bear cam, I’ve been reading the Katmai National Park’s ninety-three-page ebook on the bears of Brooks Falls. So far I’ve learned that brown bears and grizzly bears are generally considered the same species, and the difference is only their geographic locations and food sources (grizzlies are further inland).

Also: Hearing and vision is estimated to be equivalent to humans, but a bear’s sense of smell, which is many times better than a dog’s, sets them apart. Bears use scent to communicate everything from dominance to their presence in an area to receptivity to mating.

11:52 AM: I miss the bears.

11:53 AM: THE CAM IS BACK.

11:59 AM: A BEAR CAUGHT A FISH. I REPEAT, A BEAR HAS A FISH. This is more or less because the fish jumped into his mouth, but I imagine that a bear will take what he can get. After fitting the fish into his snout, then sulked away onto the shore, out of view of the cam.

12:04 PM: The camera is now trained on the sole bear still out fishing, at the bank opposite the camera. This one is a dark brown-red, with bits of golden hair on the tips of his ears. I’ll call him Tippy. He’s just standing knee deep in the water below the falls, looking around for something to swim past. He doesn’t look like he’s close to catching anything, but he’s having fun. It’s more about the chase than the prize, right?

Ooh goes Tippy for a fish! He lunged, but came up bare handed.

12:08 PM: Lol puns.

12:10 PM: I would like to swim in the river. It’s hot in here. I’m also getting very hungry. I’ve decided if Tippy catches a fish, I’m going to make myself an omelette; I now have skin in the game here. Gooo Tippy go!

12:14 PM: The camera panned away and I can no longer see Tippy. I wonder if this means I can never eat again.

12:16 PM: The cam is frozen again. I guess I’ll eat lunch.

1:12 PM: After a half hour of staring at the cam as it constantly lurches from buffering screen to buffering screen, I’m starting to wonder if I should give up due to technical difficulties; I’ve reached the point where this has stopped being a novelty and become a test of endurance. I am not tired of the bear cam, exactly, I’m just starting to think of other things I could be doing, like going to Target or watching a meaningless sitcom I’ve already seen on Netflix, and I’m powerfully aware of how hot it is in my living room. There is a window unit AC, but it’s not powerful enough to cool the entire room. Perhaps I’m having a hot flash. Can you have a hot flash at twenty-six?

The bear cam is back, and has turned itself to the right to look further down river, where two bears are froclicking in a shallow rocky patch of the river. A couple hundred feet down river from the bears, there appear to be three men fishing mid-river. Just a couple hundred feet from a pack of bears. My boyfriend just yelled, “Get away from the bears!” (He’s here too.) I wonder if these fishermen are catching salmon that would otherwise go to the bears, because human jerks can leave nothing to the animals.

1:22 PM: These bears downriver seem smaller than the ones at the falls. I wonder if they are lady bears.

2:56 PM: I fell asleep. I’m awake now. The fishermen have moved further up the river, into bear territory.

2:57 PM: Definitely all men. Ban men.

2:59 PM: When the camera pans back and forth along the river you realize how little perspective you get on the bear cam. It’s easy to forget that this one little spot is just a tiny part of the river and forest that make up the bears’ habitat. You’re strangely looking at this crazy nature thing going on live thousands of miles away, and it’s more real than, say, an edited and packaged piece of “reality television,” but at the same time, the viewer’s perspective is limited to whatever angle the camera happens to be at. You see a limited version of what is going on at this place, but it is nothing like actually being there.

I wonder what Susan Sontag would write about Slow TV.

3:34 PM: Getting tired. Resorting to screenshots.

3:40 PM: Just realizing the name “bear cam” really ignores the large numbers of seagulls on the river. There are dozens of the rat-like sea birds around.

3:52 PM: Bear butt.

4:14 PM: I might be getting bored. I’m learning more about how the bears interact with humans as I make my way through the Brooks Falls bears ebook.

From Page 47:

#854 has learned to associate people with fish. In the lower Brooks River, she will often sit or lie on the shore while people fish nearby. She often looks like she is resting and not paying attention to the water, but when someone hooks a fish, she quickly enters the water in pursuit of an easy meal. Anglers should be especially careful around bears and remember that the sound of a splashing fish is the sound of food to a bear. Each time a bear takes a fish from someone’s fishing line it reinforces that behavior. The bear is then more likely to approach people in the future with the idea of obtaining food.

4:23 PM: The camera zoomed in on a bear who had caught a fish and was eating it on the shore. I learned why so many seagulls were around: Once the bear had enough, the seagulls began fighting each other for the fish scraps.

6:24 PM: Cub alert! three cubs playing in the grass! (This is technically outside the scope of the 8-hour livestream, but I tuned in again and THERE ARE CUBS!)

They went for a swim, now they are sitting down having a snack with mom.

The Scourge of Vine Cover Artists

by Helen Holmes

The most popular Vine vertical, by far, is the comedy page, wherein inexplicably famous mostly male young people produce inexplicably adored six-second clips of themselves rehashing inexplicably popular memes in order to make a quick (and massive) buck. Some of these Vines are barely tolerable, and some of them are very bad. But the worst Vines, aside from the ones featuring a man peeing into his own mouth or white kids spewing actual hate speech, are singing Vines. At least selfies are silent.

YouTube, whose oft-successful manner of musical content production — wherein people with good voices attempt to crowdsource fame (see: Justin Bieber, Tori Kelly) — spawned this behavior, is the perfect arena for discovering blossoming Grammy winners before they blow up. Listening to Tori Kelly is like listening to a flawless Disney Princess with a little bit of twang, and she can play the guitar with a deftness that’s impressive to anyone who picked up the instrument for five minutes in high school but quickly got frustrated (guilty). She’s adorable, and has just released a crop of original songs that sound nowhere near as good as she does, alone in her bedroom, belting Michael Jackson.

But can you imagine anything worse than a pitchy Mariah imitation on a six-second infinite loop, repeating until the sun explodes?

To trace the origins of the most unbearable singers on Vine, it’s necessary to revisit Karmin, a boyfriend-girlfriend duo who first took the Internet by storm four years ago with their cover of Busta Rhymes’ “Look At Me Now,” which currently has just over ninety-seven million views. Seated behind an electric keyboard, Amy Heidemann, the female half of Karmin, adopts a nasally tone as she sings the song’s complete set of lyrics off of cue cards. I’m ashamed to say that I was enamored with this video when I first saw it: There was something intoxicating about seeing a beautiful, impeccably made-up white woman nail every syllable of an extremely complicated rap. For reasons that are all too obvious to me now, I remember thinking: I could totally do that.

Time passed, and Amy bleached her hair, and Karmin released a crop of modestly successful, highly produced pop fare (“Brokenhearted” is actually a pretty decent jam). Most recently, the heterosexual pair can be found talking about how eager they are to get married. “I want our wedding to be a gay wedding. Gay weddings are more fun than straight weddings,” Heidemann said. Their success, one of the purest indications of the power of internet popularity, is almost directly responsible for the insipid crap now circulating in droves on Vine under the hashtag #6secondcover.

The six-second cover, an idea which has since exploded to include everyone with a Vine account compelled to croon a few bars, is, both formally interesting and troublesome. Filming in the safety of home makes doing an acoustic or acapella cover of any song very simple, and this opportunity has compelled hundreds of thousands of musicians, primarily white ones, to use social media to broadcast their knowledge of “Ignition (Remix)” and the like. As Judnick Mayard recently put it: “Being black is the coolest thing because it is currently (and always has been) the most dangerous thing to be in this country.”

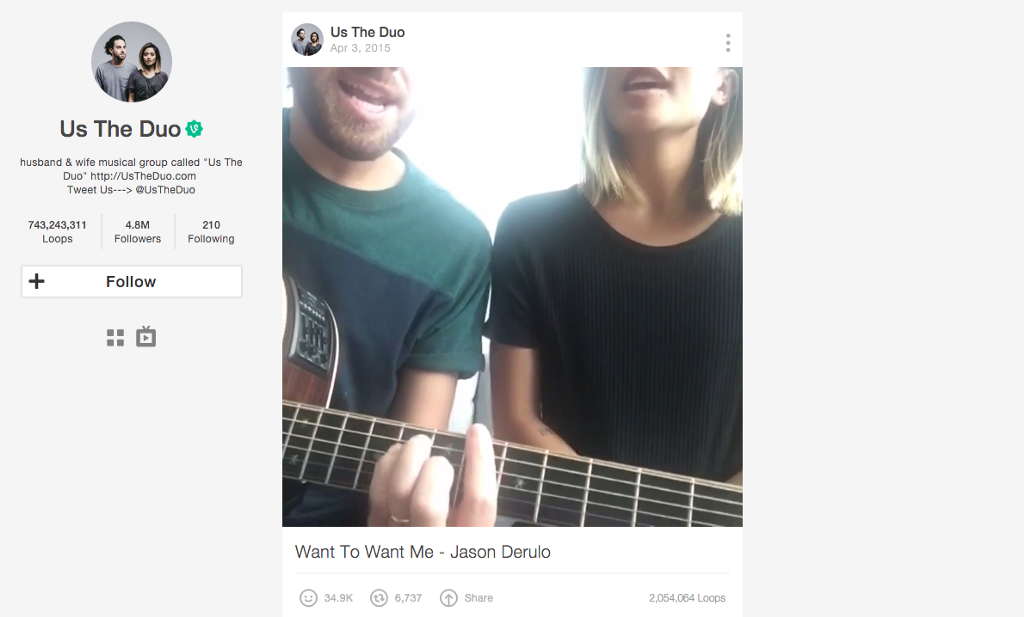

Us the Duo, the faulty grammar of which burns me to my core, are the worst. In the mold first hewn by Karmin, the band consists of a pair of good looking white heterosexual adults breaking their backs to cover Top 40 hits as soon as they come out.Vine Wiki has a concise and helpful explanation of Us the Duo’s career:

Us the Duo posted their first vine under the hashtag #6secondscover. The vines they posted were covers of Destiny Child and The Neighbourhood. The account gained over 1M followers within 30 days of their first post. Following major success on Vine, Republic Records signed Us The Duo with them and released their first studio album “No Matter Where You Are”. The album became #9th on the Itunes Pop Album Chart and Top 30 in the overall Album Charts. The group have been to various interviews and shows from Oprah to Good Morning America.”

Vine’s format makes them infinitely more infuriating. Seated close together behind, yes, an electric keyboard, the two cram their mouths into the iPhone camera’s tiny frame as they beatbox and harmonize their way through classics such as Fall Out Boy’s “Uma Thurman” and “I Don’t Like It, I Love It” by Flo Rida (Ft. Robin Thicke). Since this is Vine, these twee clips of course loop endlessly.

I hate you, Us the Duo. Go bother your miserable extended families at Christmas with this garbage. In conclusion, Zayn saved my life.