Masayoshi Fujita, "Tears of Unicorn (Vibraphone Version)"

I can’t overstate how much I am enjoying Masayoshi Fujita’s Apologues. Watch this solo version of the track “Tears of Unicorn” and then compare it with the album version. (Here’s an actual review.) Even if you are someone who usually has an aversion to the vibraphone I have to believe that there is something on this record you will be able to enjoy.

New York City, September 13, 2015

★★★★ A steady drip in the predawn dimness, some remnant of the pattering rain at bedtime, seemed to be coming from inside the room, up by the bookshelves. Full wakefulness was required to establish for certain that it was outside. The day to which eyes reopened hours later was clear and sharply detailed: lampshades in apartments across the avenue, balconies off in New Jersey, aircraft over the Hudson. A small plane banked and turned, showing the white of its wings. There was a cool, lively breeze to match the light. Down at far west 34th Street there were white peppercorns of clouds through the new glass canopy over the new escalators up from the deep new 7 train station. Immediately to the west, the clouds formed a blinding sheet that made it hard to look at all the cranes. The eight-year-old struggled to unfold and read the revised transit map in the wind. Happy people wandered around taking pictures. No transit or development improvements had made up for how sneeze-inducingly sun-blasted the open concrete of Eleventh Avenue was. In the time it took to walk from the new subway stop to the old elevated rails of the High Line, the clouds had begun to predominate. The seed heads and bright purple flowers shook in the gusts through their replicated accidental meadow-space. Reflected clouds filled the available panels in an unfinished glass wall. Enough sun came back for the return trip that the cooled air of the subway was a palpable minor relief. Later, uptown, the picturesque variety of whites and grays suddenly flattened into a single shade and rain came rattling down. Within the hour the clouds had pulled apart again to resume their dramatic contrast and motion. A small but color-soaked sunset showed in a gap between buildings, and then the sky was all iron and silver and steel. The apartment door rattled in its jamb; the wind crooned and shrieked notes on the building that hadn’t been heard in months.

Welcome to the Block Party

In a 1997 segment on the short-lived tech TV show The Site, host Soledad O’Brien sits at a bar in front of a laptop computer, talking to Dev Null, a full-scale human avatar with frosted fuchsia tips and a soul patch. Motion-captured from the show’s second host backstage, he swivels from side to side, arms swinging at their joints like a marionette, jaw moving up and down as a crude stand-in for a talking animation. The clip of their discussion of recent tech news is awkwardly edited, and a huge chunk of the conversation is cut out before the avatar breaks in with a choppy laugh. “It sounds like web heaven to me, but I guess that some of the content providers weren’t so thrilled about it,” he says.

“But if you strip banner ads out of most websites… isn’t advertising really how the web is supported, financially?” O’Brien replies.

Based on the air date, July 10th, it’s possible that they were talking about the then-newly trendy practice of turning off the “auto-load images” setting in the most popular web browser at the time, Netscape Navigator. The setting had existed since version 1.0 was released in 1994, but around late 1996 and early 1997, people began to realize that they could use the setting to prevent the internet’s burgeoning population of banner ads from loading on their favorite websites. (It’s also possible that they were discussing Internet Fast Forward, an early plugin for Netscape Navigator that blocked ads, cookies, and… blinking text.) Null answers O’Brien, “Oh basically, yeah, you’re undermining the entire infrastructure of the web, sure. But at least you don’t have to see commercials.”

Gawker has one of my favorite shamelessly aggressive pop-up ads on the internet. On any piece that seems to be getting a modicum of traffic, a silent, autoplaying video loads about ten seconds after the article does (preceded by thirty or so tracking scripts). There is a tiny link to dismiss the ad in the corner; if your cursor aim is not true, and you try to click, it will open you a second tab for whatever product it’s hawking. The videos last only a few seconds, which I used to spend being angry and impatient, but now I find it’s enough time for me to reflect on what I’m paying, and what I’m getting in return, and how long these transactions are really going to last. The ad can be skipped in 5, 4, 3, (take aim) 2, 1, and the link leaps out from under my mouse as I click. Another favorite: The other day, I took a break from reading an article on this website to check out some towels. I browsed the options, assessed the prices, and decided they weren’t right for me. I went back to the article I was reading. There, on the right side of the page rail, was an ad for the towels I was just looking at, from the same store. I didn’t even have to refresh the page.

Display ads on websites have only grown more aggressive in the last two years, taking up ever-expanding amounts of space, bandwidth, and attention. Interstitials that load as a separate page — or pop-ups, which load over the content and require a click to dismiss — are more popular than ever, especially on mobile; video ads that play automatically, too often with audio, have creeped onto more and more pages, which are themselves so engorged by the number and weight of ads that they take forever to load. And, to fill ad space on their sites, most publishers use third-party networks that often place tracking cookies on each user’s device in order to sop up information that can be used to serve new, more personalized ads, or to collect information that could be aggregated, repackaged, and sold to other marketing agencies.

A few months ago, the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at the University of Oxford released its Digital News Report 2015. One of the products of the current online ad environment, according to the report, is “significant consumer dissatisfaction with online advertising, expressed through the rapid take up of ad blockers.” Another, recent report from Adobe and PageFair, a service that attempts to monetize users who block ads, estimated that sixteen percent of people in the US block ads. In some pockets of the internet, the rate of adblocking has always been high — according to Adobe and PageFair, 26.5 percent of people who visit gaming websites block ads, and at a tech website I used to work at, even five years ago, the rate hovered around thirty percent — but according to the Adobe report, usage of adblocking software has grown forty-eight percent in the US over the last year.

In June, Apple announced a new class of “content-blocking extensions” for iOS 9 and OS X that would allow developers to create extensions for Safari that “block cookies, images, resources, pop-ups, and other content,” like scripts for ad networks, before they even load. While ad-blocking extensions have been around for desktop browsers for well over a decade, it was a tiny declaration of a new era in the mobile internet. The response to one early content blocker in development for iOS 9, called Crystal, has been borderline rapturous, especially since the developer, Dean Murphy, revealed benchmarks showing that it makes pages load, on average, nearly four times faster using half as much bandwidth, all while blocking third-party scripts that would compromise privacy. The verdict on how mobile ad-blocking will affect publishing and advertising has been near–unanimous: “A reckoning is coming.”

The central philosophical dispute over ad-blocking goes something like this: Publishers have no right to force readers to be exposed to certain kinds of ads or allow numerous third parties to collect their information without a prior agreement; readers have no right to read or view content that they don’t pay for in one form or another, be it with money or data. What is not in dispute is that if ad-blocking becomes ubiquitous (and there’s nearly every reason to think that it will be!) it will be devastating for publications who derive much or all of their revenue from advertising — which comprises most of the professional publications on the internet. When Murphy first posted about “an hour with Safari Content Blocker in iOS 9,” he asked, rhetorically, “Do I care more about my privacy, time, device battery life & data usage or do I care more about the content creators of sites I visit to be able to monetise effectively and ultimately keep creating content? Tough question. At the moment, I don’t know.” (With the impending release of Crystal, it seems he’s resolved that tension.) When I spoke with Chris Aljoudi, lead developer on uBlock, an extension that tells users how many third-party scripts are active on a webpage, and asked how sites should sustain themselves if all of their ads are blocked, he replied, “I’m not an expert on whether it’s a business model, I don’t think we need to know as developers of a tool like this.” Even if they don’t have solutions, “users need to be able to control what they are forced to come across,” Aljoudi said, using the example of nytimes.com, a website for which no known mandate of visitation exists.

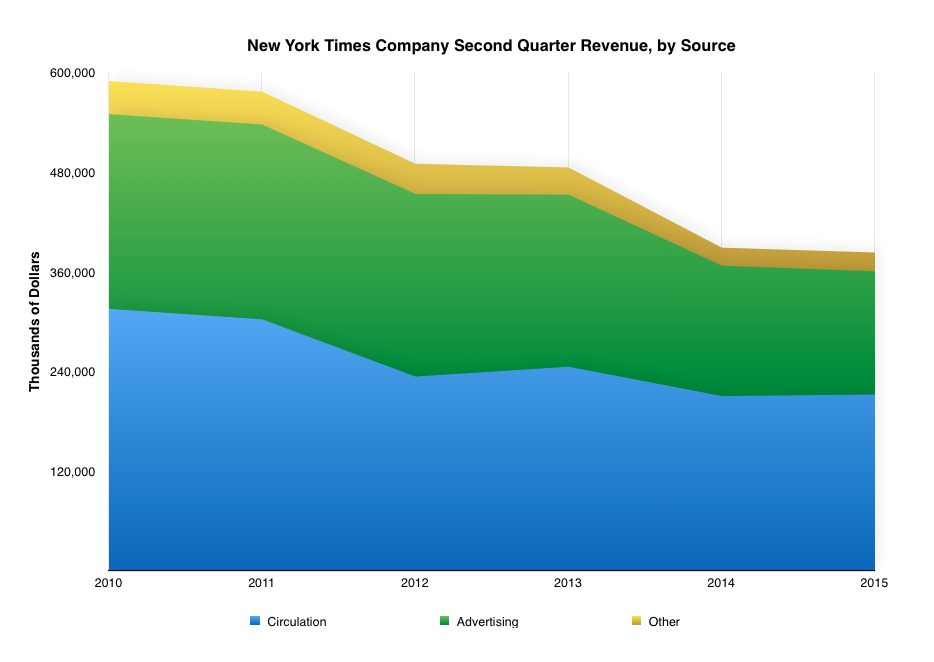

In 2014, the total operating cost of the New York Times Company was around 1.48 billion dollars (it is on track to shrink slightly this year), roughly three hundred million dollars of which goes toward “news gathering.” The Times Company is supported by a mix of revenue streams, of which “circulation” is the largest, followed by advertising. It recently hit a milestone of one million digital subscribers — at which it has “plateaued” — in addition to its roughly six hundred and twenty-five thousand print subscribers. Even though the Times has been on a forceful subscription drive, advertising still provides roughly forty percent of its revenue, according to its most recent quarterly earnings report. Unsurprisingly, given that it now reaches a hundred million unique visitors a month, digital advertising — particularly on mobile — is a growing percentage of that mix, but overall, in the quarter, advertising revenues are down 5.5 percent percent year-over-year, while circulation revenues are up less than one percent (breaking a multi-year slide, as you can see above); the end result is a net revenue decline of 1.5 percent. In other words, even the most important and widely respected newspaper in the world is nowhere close to being healthily monetized, especially not by the small number of people who pay for it.

The math is even starker for smaller publications and individual bloggers, who rely more heavily on display advertising — and who have already been battered by shifts in the advertising market; some longtime professional bloggers, like Heather Armstrong, have given up writing their blogs full-time. The Awl’s publisher Michael Macher told me that “the percentage of the network’s revenue that is blockable by adblocking technology hovers around seventy-five to eighty-five percent.” Currently, readers use an ad blocker on around twenty-five percent of all pageviews. Nicole Cliffe, one of the founders of The Toast, said that “adblocker is brutal for us. And people always break out the ‘Subscribers model! I donate twenty bucks a year!’ thing but it doesn’t add up.”

Indeed, Marco Arment, the creator of Instapaper, which copies content from websites and more often than not strips out advertising, and The Magazine, an iPad magazine that died after its subscriber base could no longer sustain it, suggests that “it has never been easier to collect small direct payments online, cutting out the advertising middlemen and selling directly to your true customers.” (Since this article was first published, Arment, who says he “make[s] most of my living from ads,” has released an adblocker for iOS.) But it is clear that most people do not want to pay with money — according to the Reuters report, despite the rise of paywalls over the last few years, only eleven percent of respondents in the US and six percent in the UK say that they have paid for online news in any capacity; the average amount paid per month per user was ten dollars (ten pounds in the UK).

The users of ad-blocking tools often view them as a force of natural selection: It is a way of letting publishers know that they love what they are selling (their content) but not what allows that content to exist (ads and trackers). Therefore, by blocking them, the argument goes, they are encouraging the system to evolve. “If advertisers would get the hint that people will surrender their eyeballs in a REASONABLE exchange, they can get what they want,” wrote one Reddit commenter in a thread about online advertising. “Like I said I never agreed to give up these impressions nor did the other users. Ads are their source of income but it doesn’t give them the right to force it down everyone’s throat,” wrote another. “Adapt or die” is a common refrain on the internet among people who do not like its prevailing business model. The other week, New York Times tech columnist Farhad Manjoo published a column on the state of adblocking, and suggested, as many people who participate stridently in arguments about adblocking do, that it has the potential to do good:

But in the long run, there could be a hidden benefit to blocking ads for advertisers and publishers: Ad blockers could end up saving the ad industry from its worst excesses. If blocking becomes widespread, the ad industry will be pushed to produce ads that are simpler, less invasive and far more transparent about the way they’re handling our data — or risk getting blocked forever if they fail…For better ads tomorrow, block ads today.

What will these “better” ads look like? One answer is that as publications transition to becoming direct content providers for the social networks and platforms whose audiences they are currently borrowing, like Facebook, Twitter, Snapchat, Google, perhaps Apple News (or Medium??)‚ many of the ads will be the same as before — placed in front of, beside, and between content — but sold and provided by the platform, rather than the publisher. Ad-blocking, insofar as it contributes to the decimation of advertising revenues, will hasten this exodus to the platforms.

And there is no way to block the ads shown to you by Facebook or Google or Twitter in their own apps, especially not on mobile. At that inflection point, the argument about how ad-blocking protects privacy by evading trackers also becomes largely irrelevant; there’s only one website I’ve found with a single third-party tracker, and one with zero trackers, according to the browser extension Ghostery: Facebook and Google, respectively. These are two of the largest marketing and advertising companies in the world, and they have to do virtually zero work in divining personal information from their users — in most cases, it’s just handed to them. Driving publishers to Facebook will not get rid of invasive trackers; it’s only declaring allegiance to the most comprehensive one, which has bought data from brokers with hundreds of millions of consumer profiles, and whose privacy policy doesn’t prevent it from selling users’ data, as long as it is anonymized (a process widely considered insufficient for privacy protection).

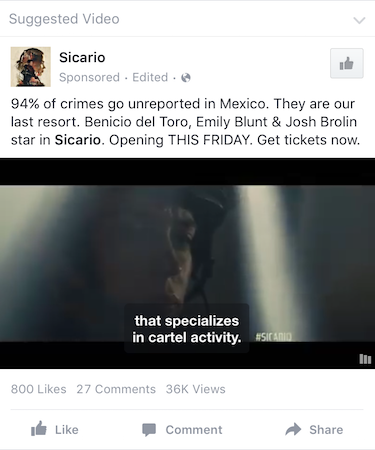

The other answer is that maybe these better ads simply don’t look like ads at all. The standard for an ad impression has gone from complex (the transaction requires a user’s click) to simple (must load on the page to register) to complex again (must load and have fifty percent of the ad by area be viewable for at least one second). Rather than playing this game, the fastest-growing media companies have figured out that the real way to make money does not involve display ads or ad exchanges at all, but native ads, which are designed to look and feel like the editorial — or at least unsponsored — content that it is next to; Ev Williams, the co-founder of Blogger, Twitter, and Medium, has espoused that today, “Native ads are the only thing that can work.” Outlets like BuzzFeed, Vice, Vox Media, The Atlantic Media, Condé Nast, and many, many others run “content studios” that develop advertising and sponsored campaigns for their business partners, often circulated through social media. While an extension can block a sponsored post on BuzzFeed’s front page, it can’t block it from your Facebook News Feed when somebody shares it, where it can reach millions of users either organically or via strategic paid placement. An extension can nix pre-rolls on YouTube, but BuzzFeed also develops video ads that are unaffected by adblocking, like a full-length video dedicated to Joe Dirt-themed lifehacks.

Perhaps the most famous example of these video’s is BuzzFeed’s “Dear Kitten” series for Friskies, segments which aired during the 2015 SuperBowl. One of these videos currently stands at 23.5 million views on YouTube. And that’s on the transparent side of things: Some sponsored content is not even well-marked. Refinery29 runs sponsored pieces that aren’t marked in any particular way on its front page; a business named LiquidSocial pays platform users to promote brands with zero disclosure. Both of these things seem to violate the FTC guidelines for online content sponsorship, but the guidelines are not proactively policed.

People who block ads are right; if this stuff doesn’t interest them it’s just as well they don’t see it. But when the ad is content being shared by people on a platform, it will be increasingly laser-targeted, and it won’t be blockable. When content and advertising and user profiles hoarded and traded by marketers are all inextricable, brand affiliations will precede users virtually everywhere they go. Desktop and mobile display ads as we know them (and block them) now will fade out, in the image of Buzzfeed, because they’ll be inferior. Blocking ads will lead to “better” ads, for some parties. Publishers that can sustain their own advertising arm can circulate sponsored content through one platform after another, using their internal data to inform their targeting strategies. Other publishers, smaller ones that hand over control of their business to platforms will get better-targeted ads, thanks to even tighter integration with the most comprehensive, all-knowing trackers on the internet; both publisher and advertisers will do better business reassured by the closed nature of apps and platforms that their ads are reaching the optimal audience who cannot escape them. And we can say for certain the pages will load very, very fast. For a while, anyway.

No Sleeping Cats

by Kevin Nguyen

My first job out of college was at I Can Has Cheezburger, where I was paid ten dollars an hour to format posts in WordPress. That might not seem like a lot, but this was 2009, and adjusted for inflation today, that would be $10.94.

On my first day, I learned two things. One was the company motto: to make people laugh for five minutes a day. The second was Cheezburger’s only rule: No Sleeping Cats.

My boss, Emily, explained that readers might confuse sleeping cats with dead cats, and the last thing we wanted to do was upset our audience with a potentially dead cat.

“Never any sleeping cats?” I asked.

“Never,” Emily said.

“Not even if they’re really cute?”

“Never ever.”

I remember this conversation because it’s funny and kind of peculiar. I also remember it because I saw the exact same conversation re-enacted on screen, three years after I’d left the company, in the opening scene of a comedic faux documentary TV series about Cheezburger that aired on Bravo, called LOLWork. Emily is in the scene, as is the CEO Ben Huh, pacing at a treadmill desk. Aside from them, everyone I’d known and worked with at I Can Has Cheezburger had been replaced by people who were suspiciously good looking. “Just as a general blanket rule, no sleeping cats ever?” asks Paul, the eccentric, bushy-haired content editor who is supposed to be me.

Emily replies, “People don’t come here to see dead cats.”

The No Sleeping Cats Rule has probably been told to just about every Cheezburger employee on his or her first day, but it’s hard to separate myself from that moment. Reliving a conversation I’d had years before was like an out-of-body experience, only with poorer production values. The archetypes of my former colleagues were there, but this bunch was more attractive. Except Paul. I should point out that the only ugly person in the show is supposed to be me.

The show could be described as “bad” and “not at all good.” Almost all of the talking-head interviews are exposition or opportunities for one person express his or her contempt for someone else. This obvious imitation of The Office is lazy, but the show does dive into strangely ambitious metafictional plot lines. In the first episode, Ben has the Cheezburger staff team up to produce ideas for a webseries that will be “like a miniature TV show” — a show within a show, right out of the gate. The fifth episode finds the office raising money so someone’s cat can have nine-thousand-dollar hip replacement surgery, so the content team decides to run a telethon, complete with talent show and a bachelor auction. The episode becomes so high concept — another show within a show — that it veers into pretension. LOLWork even has the audacity to feature someone performing Hamlet’s “to be, or not to be” soliloquy translated into LOLspeak. All this teetering back and forth between clever and inane makes it impossible to know just how self-aware the show is, what exactly it is trying to project, and to whom.

If there is a bright spot in the LOLWork, it’s watching the show do its best to establish romantic tension as quickly as it can in its six-episode run. The prospective pair also happen to be the most attractive people. There’s Forest, a content editor who possesses the anxious charm of Adam Scott, and Sarah, the quiet art director who hides behind her bangs. The show does little to disguise that their courtship is manufactured. In one episode, Emily prods Sarah about her feelings toward Forest, as if it is entirely normal and appropriate for your boss to ask you if you want to bang your co-worker. Still, this is where the cynicism of LOLWork’s cast is best employed. When asked about Forest and Sarah, some of the coworkers are nosey, while others remain apathetic. Will, the content supervisor, says, “Watching Forest try to pick up on Sarah is like watching a dog hump a pillow. You just want to look away.” Later, he delivers the series’ best line: “Listening to straight people talk about dating is very exhausting.”

More than two years after the show had ended, I emailed Forest to see if I could ask him a few questions about LOLWork. We never overlapped at Cheezburger, and he had since left the company, so he was happy to talk. Forest explained that while the show was not scripted, it was “highly directed.” No lines were given, but each scenario and situation was planned out by the producers. The same scenes were played out multiple times to catch them at different angles. When I asked him what LOLWork’s semi-fictional depiction of the work place was attempting to evoke, he urged me to not read too far into it.

He talked at length about the artifice of reality television — not necessarily a new idea, but one that was interesting to hear from someone that had been party to the charade.

The biggest surprise was that his relationship with Sarah was actually genuine. Or at least it became genuine: Forest and Sarah started dating toward the end of filming, and their relationship continued for another year before they broke up. Sarah reiterated the same notion: “Our relationship was genuine. A lot of it we actually had to hide from the cameras, rather than play it up.”

Two years since LOLWork aired, no one from the show except Ben and Emily are still at the company. Though it grew quickly in its early years, I Can Has Cheezburger’s growth flattened as its users moved from reading primarily on desktop computers to mobile devices. Ben raised an additional thirty million dollars, raising the stakes of what Cheezburger had to become to remain profitable. I heard stories from old colleagues that when the round of investment was announced, Ben went around the office handing out envelopes filled with a thousand dollars in cash to each employee. (This is not dissimilar from what Shane Smith did before VICE’s 20th anniversary party.)

In April of 2013, a third of the company was laid off. In tech lingo, you might say the business “didn’t scale.” Ben writes somewhat regularly on Medium about what it’s like to manage the company. He’s reflective on his own shortcomings and the decisions that led to the company’s failures. In a post he concedes that venture capital transformed the company into “a confused, money-losing mess.” This past July, Ben stepped down as CEO. In his farewell post (obviously on Medium), he wrote, “The time has come for Emily and I to go on another unscripted adventure, without a reality TV crew.”

There has been a recent trend in treating business failures as a badge of honor, particular among startups. This, unsurprisingly, is how people talk about failure when they risk nothing, when you’re in your early twenties and playing with someone else’s money.

I wonder what LOLWork would have been like if it had been on long enough to see the company diminished. What if the show possessed Ben’s newfound self-awareness? This version of Cheezburger, the one in decline, is the one I wish I could see. But that probably doesn’t make good television. I rarely tell anyone that I worked at I Can Has Cheezburger anymore — not because I’m embarrassed, but because people are usually disappointed when I don’t have funny anecdotes about it.

The only notable story I have is about my weirdest day of work. During a period of rapid growth, Cheezburger shared the floor with a medical supply company that was not doing as well. A couple months into my brief tenure, their entire sales team was abruptly laid off. The company sold machines that prevent sleep apnea; I asked a colleague what sleep apnea was exactly, and she described it as a disorder that causes breathing issues during sleep, the most serious of which could cause strokes.

“So the machines they’re selling prevent people from dying in their sleep?” I asked.

“Yes, literally that,” she said.

When I went to the kitchen to microwave my lunch, I saw a woman sobbing and asking herself out loud how she was going to find another job. I didn’t know what to say. It seemed unjust that a company that actually made people’s lives better could be on the rocks, while a bunch of poorly dressed nerds who posted dumb pictures on an even dumber website would flourish. Instead of saying anything to the woman, I took my lukewarm Thai food and went back to my desk and to upload some photos of Lady Gaga into WordPress.

Later, I saw Emily consoling some of the supply company salespeople, offering them free Cheezburger merchandise like t-shirts and stuffed animals from our unsold inventory. It seemed half-hearted, but it appeared to cheer up at least a few people. People smiled, and it was the first moment I realized why the site had captured such a massive audience. All good comedy is about timing. It turns out making people laugh for five minutes a day could be important, if you caught them during the right five minutes.

A longer version of this essay appears in the anthology Cat Is Art Spelled Wrong, available from Coffee House Press on September 15.

Photo by Alexandra Guerson

If You're Still Reading Fiction, Read Percival Everett

The short stories in Percival Everett’s Half an Inch of Water are deceptively simple, and yet you finish each one with a distinct sense of unease and and weird wonder about what just happened. (In the best way possible.) These are good, solid stories that leave you feeling differently than you did when you started them, and really, how often does that happen anymore? Everett may be the best American author writing today, but even if you are someone who prefers the Jonathan Franzens and Jennifer Weiners of the world you will still find plenty to enjoy here. The man doesn’t waste a word. Would that this were so of everyone else. I will just urge you to pick up a copy of this book and go silent myself. You’re welcome.

Darkstar, "Stoke the Fire"

Please don’t let the nice weather today trick you into thinking everything will be okay. It won’t. The weather will change and everything will still be bad, but not so bad that you won’t be wishing for it once things get worse, which they will. Anyway, weather like this can only be enjoyed for what it is: a temporary respite from the parade of aggravation and sadness that is your life. Take whatever comfort you can while you can and never get fooled that it’s anything permanent. Speaking of brief but pleasant things, this song is nice. Enjoy it.

New York City, September 10, 2015

★ Rain fell in the dark, sleepy morning. It took a sudden wash of sun, and the project of looking for rainbows, to pry the slumbrous three-year-old out of his bunk. The air outside had cooled off but was still uncomfortable and thick. The rain started again and stopped again. A few fresh drops were on the pavement on the way to the elementary-school pickup. Before the class got out, the rain was coming down so hard it was necessary to retreat to the scaffold over the driveway. Water was dripping steadily from the roof of the far-right-hand elevator, the air conditioner overwhelmed by the sogginess. When it was time to run out to get milk before dinner, the radar map said there was no shower, but a light rain was coming down anyway. There was nothing autumnal in the sweltering gray, but there was in the haste with which the daylight failed.

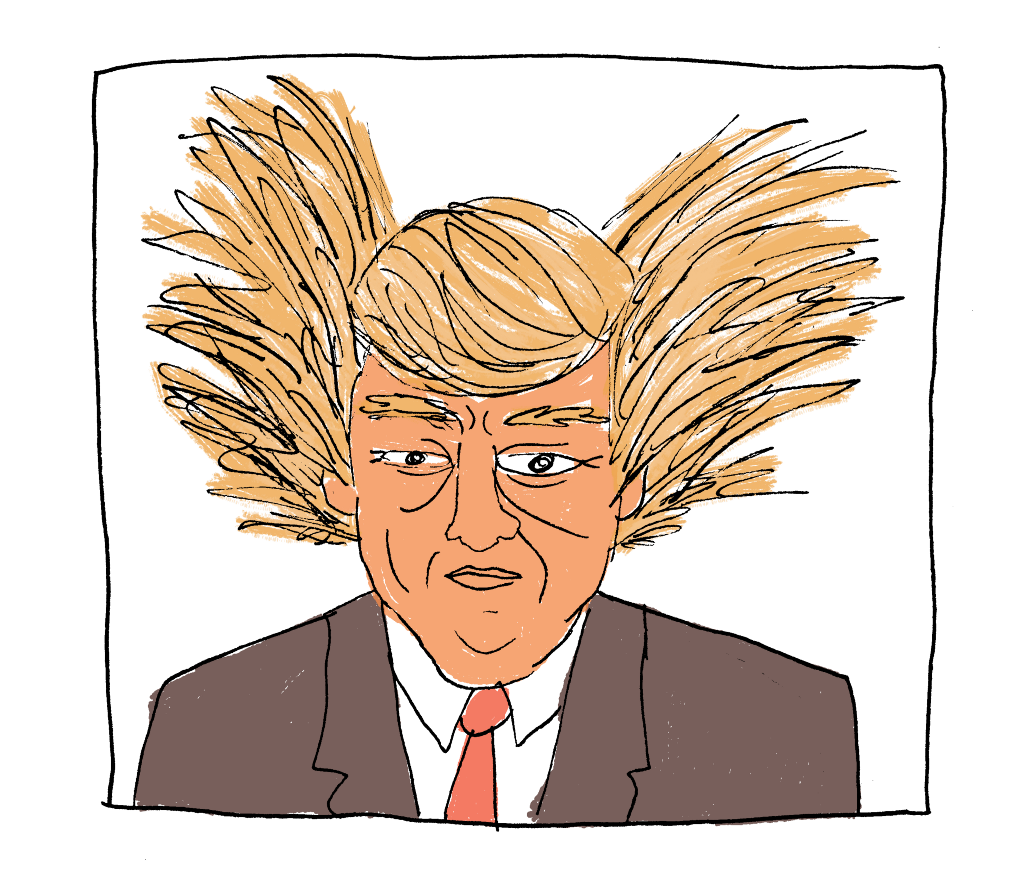

Some Mild Suggestions for Donald Trump's Hair

by Hallie Bateman

“I would love to crop it short on the sides, keep the top a bit long. I think we’d really need to move him away from that weird orange color. Maybe give him some highlights — not so he’ll have highlights, but just to transition him to his natural color. Gray, or whatever. It’d be like restoring an old building. I think that would help a lot…. I don’t really want to help him, though.”

— Luke, Soon Beauty Lab, Fort Greene

“If he’s a man, and wants to show he is a true leader, he would make it shorter. Take out the piece and walk like a businessman. Trim it close and keep it natural. Don’t try to cover it up.”

— Albert, L’Mosh Aliz Unisex Salon, Upper East Side

“Cut it all off. Totally bald.”

— Tony, Cle’s Cuts, Bed Stuy

Irina: I think he should get extensions. Or, what are they called… Hair plugs. It’s not his hair but it would look nice. Just nice bangs. Or spike it. He’s gonna be more handsome than his style.

Lana: Maybe he’s scared to get the surgery. People come in here who’ve had it done. They take [the hair] from the back. It grows!

Irina: He has the money to do this. This is the best way.

Lana: This is the best way. Don’t be scared. Any new procedure is scary.

— Irina & Lana, Svetlana’s Hair Salon, Upper East Side

“The hairstyle is so bad. His style is so bad. The middle part is too long. Cut at least 2 inches at the side. At the center cut 3 inches. In the back, cut 1.5 inches, with some layers. Color is so bad. A little darker at the base and have some highlights. I want him to look good. It doesn’t mean I criticize him. He should come to our salon. Tell him my name is Butterfly. Our price is not high but we tell the truth. Our price is inexpensive! Congresswoman Carolyn Maloney is our customer, too.”

— Butterfly, Farfalla Hair Salon, Upper East Side

“I saw him once. I was jogging and I saw him getting into his helicopter. I saw his hair and thought: “no way.” … I’d try to cut out the top, part the hair in a normal place, make it shorter on the sides… It has to be shorter and not too blonde. Dark blonde. Not as light as he has now but not one color tone. It’s not working for him.”

— Freddy, Bleu Sur Bleu Hair Salon, University Place

“Like fire to the sides. Like Sonic. But still keep the bangs because that’s Donald’s signature. But gotta get the fire going. Because, if you think about it, he pretty much has the same personality as Sonic. Crazy. Wild.”

— Sean, Heads Up Barbershop, Downtown Brooklyn

“I would change is color. More ashen than warm. Still light, mixed with grey hair. This color is too warm for him. It eliminates his features. He has a beautiful face. It’s going to be a nice, convenient haircut. He’s going to be President, right? Or not. It’s always yes or no, isn’t it. Life is fun. Send him over here. I fix.”

— Leonid, Vanilla Hair, Upper East Side

“He has to stop doing the comb over. Like the rest of the nation, he should cut it short on top and make the best of it. Or else, shave it.”

— Anonymous, Supercuts, Upper East Side

“Part of me loves it the way it is. It’s a whole separate entity. His hair could just live by itself. His hair could be a separate candidate altogether… Would Cousin It be Cousin It without his hair? Would Don King be Don King without the fro? How could you change it?”

— Franco, Cutler Salon, SOHO

Previously: The Trump Fantasy

Nothing Lasts Forever, Not Even Your Brief Window of Dominion Over Your Home

“Every inch of Manhattan real estate is in play, even the once-sacred co-ops,” said Adam Leitman Bailey, a lawyer who represents Mr. Selbert. Mr. Bailey, who won a temporary injunction to stop the collapse, or legal dismantling, of Mr. Selbert’s co-op, said he has a dozen clients in similar situations and that the number of cases he is getting has skyrocketed in the past 18 months.

The buildings most at risk of being caught in the cross hairs are in popular neighborhoods, have unused air rights or lucrative retail spaces on the ground floor and have just a handful of apartments. But buying three-quarters of the shares is no easy feat even in the smallest of co-ops. Multiple shareholders must be convinced to sell, which can lead to infighting and lawsuits among neighbors.

God help you if you live in a building with untapped air rights in a neighborhood that people would like to move to.

Photo of unrelated apartment buildings by Jeffrey Zeldman