Leo Abrahams, "Chain"

“The sound of [Brian Eno’s] stacked vocals is, for me, one of the greatest sounds in music history,” says Leo Abrahams of this track, in which that sound does indeed play a prominent part. Enjoy. [Via]

New York City, September 15, 2015

★★★★★ The light in the street was a stage-lighting treatment of daytime, so that a Mercedes, not a particularly well-kept one, gleamed down to its hubcaps. The temperature was a tiny increment higher than ideal for long sleeves; there was a little eyestrain at the crosswalks. This was summer again, remnants tidily packaged. Loose open-backed dark shirts were falling off tanned shoulderblades while they still could. The air conditioning had gone fully insane — it took layers and a raised hood to fight it off. Eventually it was time to take off the layers and go out, to stand on the far, sunny side of Fifth Avenue, by the gutter full of dry trash and sediment, absorbing the gentle blessing of the heat.

My Superpower Is Being Alone Forever: Off the Market

by Joe Berkowitz and Hallie Bateman

Some people say they have no regrets. I regret things about this morning. (Also yesterday morning. Pretty much any morning.) Show me a person with no regrets and I’ll show you someone who hasn’t considered all the possibilities. It’s this kind of catastrophe-awareness, though, that can make dating feel impossible. By the time you’ve been through a few relationships, it’s hard not to size up anyone you have feelings for as an ambassador of future regrets. Time misspent. Integrity diminished. Memories that follow you everywhere like Pac-Man ghosts.

Every new relationship is a potential future ghost. It takes an almost delusional level of optimism to ignore the possibility. But we try our best. We’re like the nomadic survivors on The Walking Dead — skeptical of new people, but maybe not enough. The dwindling principal cast on that show always stumbles on a fresh community, gives them the benefit of the doubt, and then somehow it all ends in a bloodbath. Still, they continue searching. Even though I’ve never personally witnessed blunt zombie-fingers rip through buttery chest cavities, I relate to The Walking Dead more than any of the infinite TV series about thirtysomething white-guy malaise. It’s the unlikely suspension of distrust. No matter how badly I’ve been ripped apart before, I never lose faith in the dream of sustainable shelter from the zombiepocalypse of solitude. When I met my girlfriend on a holiday party couch, starting a conversation about her electric blue pants of all things, a voice in the back of my head was already whispering that maybe this time it will be better. Maybe this time it will be the last time.

Very few people up and join a cult as soon as they enter a prayer circle in the freegan farmhouse. Instead, they’re honeypotted with promises of enlightenment, and only gradually discover the creepy clause in the contract. By then, it’s too late and you’re already eliminating suppressive persons from your life and accruing operating thetan levels like cub scout badges. Similarly, when you start to see someone, all you see is their best stuff — the premium anecdotes, conveniently aligned opinions, and outfits with accent pieces. There’s no way to know the other details right away, like whether this person has ever had bedbugs or played quidditch. If we did, we’d all be making sober decisions early on instead of slowly revealing our dealbreakers by hanging out together. Once you get to know someone beyond the way their face makes you feel or their perfectly timed joke about Law & Order: SVU, once you memorize their scars and befriend their pets, it might dawn on you that you’ve finally met someone who ticks all the boxes and even adds new boxes. By the time you lose track of which outfits this person has seen you in, and stopped conditionally customizing opinions, it’s too late — you’ve joined a cult of two, like couples who CrossFit.

If you could train two puddles of vomit to say “I miss you already” a thousand times a day, it would be an accurate performance art piece depicting couples in their Honeymoon Phase. Aficionados would applaud your attention to detail, and Marina Abramović would petition to adopt you. “Honeymoon Phase” is a misnomer, though. An actual honeymoon is just an echo of the initial infatuation, with an all-inclusive resort tacked on. By the time most couples get there, they already know each other so well that any surprises count as full-blown betrayals, signaling a possible invasion of body-snatchers. But during the infatuation phase, even just discovering that my girlfriend also craves fried pickles or that she used to play the violin registers as news worthy of World War III headline font. Infatuation is nostalgia’s cool cousin who knows how to party. Staying in on Friday night is now a slumber party with your best pal, where you order Indian food, watch a horror movie, drink whiskey, and mess around. You feel like geniuses for figuring out you can even do this, and everyone else seems like idiots for being with anyone else. Boring stuff is exciting again, experienced through the new prism of We. That nine-hour train-ride to Vermont just whizzed by! Every new way you spend a Saturday has an aura of infinite possibility. This could be how it is from now on: so wonderful and disgusting everyone else could just puke.

Unlike companies on the New York Stock Exchange, only after single people are off the market can they go public and issue a relationship-IPO. Friends and family receive the announcement happily, but are unsure how much emotional capital to invest, without seeing key performance indicators. Everybody asks whether you two are getting serious, despite the fact that this is a bizarre question. (What are you supposed to say? “It’s actually not serious?” “We make love in the style of Monty Python?”) Now the stakes are suddenly higher. If it doesn’t work, you have a lot of ret-conning to do about why you were never right for each other to begin with and how this is for the best. So you make plans for the future, putting tiny down payments on staying together. You establish routines in dinner preparation chores, along with backrub style and duration. You experience a conscious coupling. There’s now a performance element to things — convincing the world as you convince each other that you’re basically the #relationshipgoals hashtag incarnate. You look to what everybody is saying, or not saying, for a sense of your street value, and hope it doesn’t turn out to be a bubble.

When things are going well, I always start to worry that the other shoe is going to drop — that there’s an entire Narnia-closet filled with other shoes. Any traits I may have downplayed at the beginning aren’t gone forever, but lying dormant. Some people say “if you can’t handle me at my worst, you don’t deserve me at my best,” but even I can’t handle me at my worst. I hate that guy! Maybe the ultimate lifehack is finding someone you want to never freak out in front of so you can trick yourself into being perfect from now on. That’s me calmly waiting while our flight delay is sorted out. That’s me, meeting her handsome guy friends with studied nonchalance. It’s not a lie if how I am for her is how I always wanted to be.

Even when it seems we’re past the point in a relationship of playing games, communication can still feel like an exercise in Cold War-era brinkmanship. We say things that seem designed to provoke, because we now know each other enough to potentially implant hidden meaning in any sentence. Each of us is basically a collection of things we’ve learned to say in different situations, which becomes a huge problem when you misidentify a situation. It always turns out that I only thought we were playing games when we weren’t — I might as well have initiated a round of chess with a cat. The only game we’re playing is taking turns on the high horse about who looks at their phone too often. And sometimes Mario Kart. If things were really this good, would I continue to worry so much, or do I only worry so much because things are really this good?

Nothing gets a new couple high on their own supply like having brunch with an inferior couple. You trade glances and sub-table knee-squeezes, aching with anticipation for the moment you can openly talk smack about them. So many other couples practically live inside a mobile dust-cloud of flying limbs while you, well, you’ve never even had a fight. Your existence is a möbius strip of montage sequences — watching the grunion run and skipping stones forever. When the first fight finally does arrive, it feels like a fluke. You make up fairly quickly and laugh it off. Just a misunderstanding that penalties out to some extra affection. How ridiculous that you were even fighting over something so stupid — you’re both such dumb idiots! It’s a little harder to make up the second time. Now, part of the fight is about the fact that you’re fighting at all and how you’re worried the spell may be broken. The slide from “We never fight!” to “We make up well!” feels like the point in a nice dream when you realize you’re dreaming.

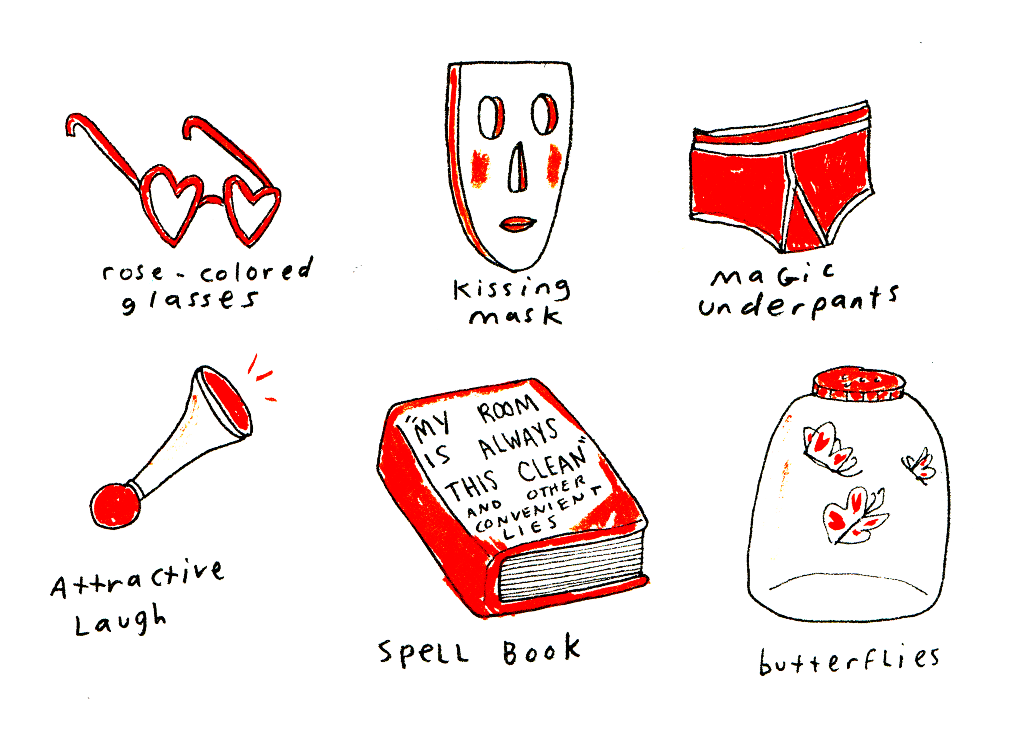

Making someone fall in love with you is a magic trick. You misdirect attention from the parts of yourself you don’t want seen, stack the deck with the parts you do, and when it works, you make the rest of the world disappear. But there’s nothing less exciting than finding out how a magic trick works. Maybe you repeat a joke about Law & Order: SVU at the exact same verbal prompt as before, and now it’s clear it was always one from your repertoire. Also, that you have a repertoire. What comes after seeing the same outfits over and over again is hearing the same anecdotes and jokes for a second and third time as you go to more parties together. Once you’re no longer a new couple, something has to replace the novelty. That’s how a magic trick ceases being a trick. People mourn when the mystery starts to wear off, but that’s when you can stop being audience to a magic show.While you’re sitting there at some party, telling the same story again for the thousandth time, you absently touch each other’s arms as though you still can’t believe you’re both there and how lucky you are it wasn’t all an illusion. Abracadabra.

Previously: My Superpower Is Being Alone Forever

My Superpower Is Being Alone Forever: Newly Single

Tightness Disdained

“I’ve long had an irrational hatred of tight clothing. A bandage dress? I’d rather actually be in the hospital. Lululemon Apparel? As John Galt once said on a Lululemon bag, ‘don’t tread on me.’ By far the worst phenomenon of the last decade has been ‘skinny jeans,’ designed by a male sadist, miniature pairs tested on dead lab rats. Women are expected to wear tight clothing to be ‘sexy,’ which is bullshit, and similarly many women say that tight clothing makes them feel sexy. The word ‘tight,’ in our current parlance, has positive connotations, as in describing someone’s excellent and modern style or the fine intricacies of the female sexual organ. But tight clothing is threatening to the body. It strangles you, it leaves marks on your skin. It is an undertaking: a person is restricted in a tight garment, and even simple tasks are difficult to accomplish.”

The Way We'll Eat Then

“Yeah, we’re going to be doing modern takes on classic Brooklyn-American food of our grandparents’ generation, and the only way to do that right is with real meat. So it’s another period restaurant… a throwback to the late twentieth-century, early twenty-first century — but at a much higher level. Think roasted pig’s belly, lots of vegetables charred in cast iron dishes and seasoned with more pork, heirloom borecole salads, steak and beef tartare and tubers, of course, and in a couple of years, aged meats. Unfortunately, not poultry or oysters — which were key to that era’s style of dining — because they’re gone, obviously. What I wanted to get back to again was this period of a certain kind of casual luxury, an era where everyone could afford to be inefficient, when eating meat was normal and natural, and we’re taking the re-creation of that culture very seriously.”

— How will rich people eat out in 2081? Here’s a preview.

Craft Spells, "Our Park By Night"

At first you will find yourself skeptical about this track but as it plays through it will settle itself into your subconscious so that by the third time the chorus comes around you will wonder what you ever doubted about it. Then you will play it again. Enjoy.

New York City, September 14, 2015

★★★★★ Light reflected and refracted all through a flawless crystal morning. The breeze gathered strength as it came up Broadway. Sweaters were out, and sport coats. Instead of last week’s hot exhalations, the subway stairs breathed in cool air. A police officer was out below the Flatiron directing traffic contrary to the signals, and then came more police and police cars, and a surveying tripod right out in Fifth Avenue, and a barrier drape, parallel to the lane markings, that did not conceal the red of a pool of blood. A block beyond, the gorgeous day went about its business. Blinding white flared into the office off the shades and blinds half-lowered on the windows of other offices, across the street. The wind flipped the cover of a paperback of Six Centuries of Great Poetry lying on the pavement by an overflowing trash can. The breeze was cool but warm, some inverse of feverishness; the buildings separated themselves from the sky like thick lines of paint coming off the brush. Bunches of wheatgrass and jars of preserves glowed on the Greenmarket. Uptown, a man sat by the curb of Broadway with a canvas propped up, at work on a picture of a building that bore no obvious resemblance to any of the buildings in his view. The wind inflated the cloth cover over a parked motorcycle. The sunset sky was featureless but orange fires burned on distant shiny surfaces upriver and downriver, and nearer at hand they seemed once more to burn straight through the tower that would stand in the way.

The Humans on the Other Side of Uber's Help Button

Drivers are far from the only form of Uber non-employee. Meet the person on the other side of the help button:

In 2014, I spent nine months as an Uber Customer Service Representative (CSR). I found the posting on Craigslist while looking for telecommuting jobs. At the time I didn’t think it would be the job I would later leave off of my resume. I interviewed with a woman over Skype whom I never met again. The offer was $15 an hour. I signed the standard non-disclosures.

Uber is not the employer of record of its CSRs: that’s ZeroChaos, essentially a pass-through HR agency that touts itself as a clearinghouse for “contingent worker solutions.” At the start of our two-week orientation we were introduced to “Hector,” who walked us through the mechanisms Uber uses for client satisfaction and tracking: programs with names like Hipchat, Zoom, Zendesk.

Of course we had other questions for Hector. Vacation time? No. Work holidays? Mandatory. Performance incentives? We’ll mail you an Uber T-shirt.

Our Racist Dogs

by Kelly Mays McDonald

The first time I encountered the 1982 movie White Dog was on a lazy laundry-folding afternoon in 2012. I’m a weirdo who is completely obsessed with dogs, and I have a bad habit of searching for the word “dog” on Netflix and watching whatever absolute garbage turns up. I think last week’s pick was Snow Buddies, the second movie in the indomitable direct-to-video Air Bud spinoff franchise about talking holiday puppies. I’m not terribly selective with my laundry-folding films, as long as they feature a dog (especially many dogs), despite the fact that I make my living hanging out with dozens of cool shelter dogs every day. So I assumed that the film was schlocky German Shepherd Hero matinee fodder for 80s tweens — gee, a racist dog… who is literally a white dog?? lol — and pressed play.

White Dog, adapted from the autobiographical novel of the same name by French author Romain Gary, is the story of a diminutive white starlet named Julie who takes in a stray white German Shepherd dog, who — oops! — turns out to be violently racist. But she straight up denies that he might be a problem for society until he maims not one, but THREE people. Three. Finally, after she inexplicably brings her giant murderous dog on the set of a commercial job, he mauls her black costar, provoking Julie to take this shit a little more seriously. She refuses to give him a name so I will just have to refer to him as White Dog.

Dog trainers have a tendency to pan animal movies for being unrealistic. Cinematic liberties are easy to take when the results of a dog behavior rehabilitation program are often chalked up to a combination of animal whispering and magic. So on that basis alone I think I spent a good 90 percent of this movie laughing to myself. Additionally, the very notion of the White Dog was completely ridiculous. A dog that’s so virulently racist that he kills every black human being he sees? How does a dog even detect skin color? Can’t they only see the colors blue and yellow? If so, do I look blue or yellow? Sure, white people’s dogs have jumped at me a few times, but they never seem to be intent on ripping me apart. Does the movie conclude with the revelation that the dog is just a furry robot programmed by members of the KKK? Does the KKK put little dog-sized hoods on their robot dogs, or do they only make custom hoods for horses?

Julie visits the city pound after the dog goes missing (to kill a black truck driver in the film’s most Stephen King-esque murder, of which she is unaware).

The shelter is brimming with poor defenseless pets waiting to be executed in an old-school gas chamber. She can’t possibly bear the idea of bringing her murderous, treacherous, gigantic dog to the shelter, or even to an actual dog trainer, so naturally she drives him to an exotic animal trainer deep in the Valley. Lo and behold, the white trainer Curruthers (played by a jocund Burl Ives teetering on the edge of senility) and his black assistant Keys (Paul Winfield, at his most strapping) happen to believe their life’s work lies in “curing” racist dogs, despite their primary focus of taming snakes and tigers for movies. Keys even volunteers to work for three weeks — day and night, without pay — to reprogram the dog with advanced training techniques such as:

- Yelling expletives from the other side of a fence while White Dog tries to bite him;

- Standing around in a full body bite suit while White Dog bites him;

- Eating hamburgers in front of White Dog;

- Lifting up his shirt to show White Dog his big brown tummy, which enrages White Dog, then rubbing his tummy to enrage White Dog even further, then giving him a hamburger for not biting the tummy;

- Waiting until White Dog is tired and then taking an afternoon nap together in a cloud of dust. White Dog is still mad, but also he is too sleepy to be racist.

Progress is derailed for the next few weeks by Julie’s guilt-fueled coddling with secret bonus hamburgers (the dog is only supposed to eat from black hands, so this is a big no-no). Despite these exploits, Keys’ training seems to be wearing down White Dog’s resolve to bite the brown tummy. Meanwhile, Julie is approached at her doorstep by a hail-fellow-well-met white man accompanied by two little girls. “Please lady, can we have our dog back?” they lisp. The man claims that White Dog ran away from the trailer park, then boasts proudly that he trained the dog himself. Julie suddenly grows a backbone and barks back that the dog has been “CURED, BY A BLACK MAN!!!” before she righteously speeds away in a roadster to witness the final test of White Dog’s newfound sanity.

Needless to say I was a little baffled by this premise, and also a little distracted by my laundry, but something about White Dog got under my skin.

Two years later, I was working as an animal behavior assessor at a small shelter in the Midwest when I was again confronted with the concept of dog racism. Whenever a dog was aggressive to me during its assessment, the shelter manager dismissed it and opted to place the dog up for adoption. Inevitably the dog would bite someone, and I would be left scratching my head and wondering why my assessment was discredited. This went on for months before I finally confronted her. Why didn’t she believe me when I told her that a dog was aggressive?

“Oh,” she said, “a lot of dogs don’t like black people but they’re fine with everyone else.” With that she flipped her blonde ponytail and walked away. Was this just a workplace microaggression, or are these dogs actually racist? I found myself grappling with the idea that not only do actual humans hate me for being black; dogs could also hate me for reasons that are out of my control. I tried to fight her claims with deep academic research into animal cognition and ethology, immersing myself in texts and academic papers to unearth the potential for a dog to distinguish human beings by shades. I already knew that, for the most part, dogs bite people out of fear, generally solicited by underexposure or traumatic experiences. For example, I meet a lot of dogs who are afraid of people wearing hats. But dog discrimination in this context is less black and white than whether or not someone is wearing a hat. How dark would a person have to be for an undersocialized dog to feel triggered? Can dogs even distinguish people by color? Do I emit a smell detectable only to dogs that denotes my status as a human being worth biting?

Later, when I was working at an animal shelter in New York City, I was mauled during a routine walk with a 110-pound dog. The ten-minute attack was punctuated by the dog’s wagging tail, happy soft eyes, and what seemed to be a physical inability to detach his jaws from my leg. “He is having fun,” I thought to myself as I passed out. “He thinks this is a game.” In the ensuing months spent hospitalized and bedridden, dog experts in the field offered their reactions, which ranged from 99 percent blaming me for being attacked, to blaming me 110 percent for being attacked. Surely, they thought, a dog would never ever bite a person without provocation, much less maul them almost to death! But after revisiting the film during my lengthy recuperation process, it finally dawned on me that White Dog, like the dog who mauled me, was not a typical pet dog. He was a highly trained soldier.

Here lies the missing link in my initial dismissal of the film’s premise. In my ignorance as someone who works with pet dogs, I was considering aggression to be what it is in its most common state, which is fear-related reactivity stemming from poor socialization. I was correct in assuming that the pet dogs that I was encountering in Illinois were “racist,” projecting their owners’ choice to exist in a whites-only world, and perhaps even reflecting an inherent bias cultivated over decades of segregation. But I was missing the framework of a world of dogs beyond pets — a world made up of of what I call “weaponized” dogs — in which dogs are trained to violently target specific populations.

What is critically important about the origins of this dog, but is lost in the cinematic adaptation, is the fact that White Dog’s trainer is not an ordinary citizen, but a police dog trainer from Alabama. Director Sam Fuller clearly revised Romain Gary’s memoir to gloss over the fact that the titular dog’s violence is specifically related to state-sponsored police violence. In the book, the man who arrives at Gary’s doorstep to reclaim the dog is actually a former sheriff whose police officer son trained white dogs for two decades: “My son’s just retired from the police, after twenty years. He plans to go into business for himself. He wants to open a kennel. He’s a professional dog-trainer. Police dogs… I used to be a sheriff, myself.”

The sheriff, like the one depicted in the film, is completely unapologetic, even proud. When confronted by Gary with assertions that the dog is racist, he replies, “Yes, Sir, he’s a fine police dog… As good as they come. My boy trained him. He’s been training them for twenty years of his life, he’s a real professional… Fido has three generations of attack dogs behind him, all in the Police Canine Corps, all trained by my boy.”

This dog is one in a long line of Southern police dogs, trained to selectively kill and maim, originating from ancestors bred and trained by slave-catchers to hunt down errant human property: “Police dogs like [White Dog], I am told, almost all have generations of specially trained animals behind them. Both training and their inbred atavistic capital of push-button hatred are ‘improved,’ that is, facilitated by environment, with its automatic way of conditioning. Untrained dogs in black sections of the South will bark at whites just as in white neighborhoods they bark at blacks. Conditioning, training, and environment snowballed through generations until this ugliness becomes second nature.”

Weaponized dogs are ever-present in humanity’s long legacy of colonialism and slavery. They have fought alongside many instances of human atrocity to perpetrate acts of physical and psychological violence that supersede the scope of a simple gunshot. European colonizers of the New World notably trained their dogs to “relish Indian flesh” by explicitly feeding them the bodies of the victims after a battle. Throughout America’s early history, slave masters and bounty hunters adopted bloodhounds as the primary means of tracking down runaway slaves by scent, which is widely depicted in popular media. What is left out of the popular narrative, however, is the fact that when they encountered people on the run, the dogs were often trained to bite and tear the flesh of slaves to hold them there until they could be shot, shackled and dragged back to their masters for public lynchings and beatings.

Ansdell, Richard. The Hunted Slaves. 1861. Oil on canvas. International Slavery Museum, Liverpool, England.

Mississippi Governor James K. Vardaman’s infamous Parchman Farm correctional work camp encouraged black inmates to violate its invisible fences in order to relish in the activity of hunting them down with ruthless bloodhounds. After decades of success in military work (most successfully by Germans during WWI), Shepherds were embraced by American police and military forces as a means of keeping specific populations under control with the threat (or more frequently, action) of maulings. Not much has changed in the past sixty years, since the famous use of police dogs to curb Civil Rights protests.

A 2013 independent review by the Police Assessment Resource Center revealed that 89 percent of people who were bitten by LAPD police dogs between 2004 and 2012 were black or Latino.

White Dog remains all too relevant, pointing to a distressing lack of progress in police dog training in the 34 years since the film’s inception. There do exist trainers such as Steve White, supervisor of the Seattle Police Canine Unit, who works tirelessly to establish standardization of sound training methods to ensure that dogs remain under control and “release” just as readily as they will bite. Despite his efforts, there is no established nationwide standard of police dog behavior, and their presence in our communities is still to be feared. Like the dog who mauled me, police dogs are brainwashed from an early age to have fun while they are “apprehending suspects,” and are often looking for an opportunity to play the “bite game” whenever their handler so much as hints at a command to attack. Popular opinion assumes that police dogs are trained to carefully follow a scent to ensure that they are catching the right Bad Guy. The reality of K9 pursuits could not be further from the truth. When there is a suspect in a general area, dogs are released by their handler to rove the area in search of whoever is in sight. When police dogs are triggered by running or quick movement, they hunt and take the trigger down with a technique called “bite and hold” until officers arrive to release the grip of its teeth from your leg, arm or neck — which is often difficult since the dogs enjoy biting so much.

Accidental discharge occurs on a regular basis, due to the trigger-happy nature of weaponized K9s and the lack of standardized training or management. In January, Norfolk, Virginia police released a K9 on a local college student for being too loud as she left a campus party; the dog tore apart her leg in several places before they were able to get him to release her. In Charlottesville, Virginia, a 13 year-old girl was maimed by a police dog who was accidentally let out of a car and ran to bite the first person he saw. Often, this hair-trigger training even leads to dogs maiming their own human handlers, like this K9 officer in Richmond, California. Sometimes police dogs who are cared for in the homes of officers attack members of their own family.

Weaponized dogs inhabit all levels of state-sponsored control, spanning from correctional dogs used to drag American inmates out of their cells, to the German Shepherds used by Ferguson police to intimidate black citizens on a regular basis. And although White Dog takes a lot of Hollywood liberties with the depiction of a former K9, we are still faced with the threat of bodily harm that can easily be dismissed as accidental. This form of police brutality, veiled in the guise of a dog’s intent, can serve to alleviate an officer from being held legally accountable for his or her own violence. Culpability is also diminished by the American public’s love affair with all things dog — although the dogs that we see in uniform are not pets, but weaponized animals encouraged from puppyhood to bite with force equivalent to being run over by a small automobile. And, like White Dog, they will continue to rehearse what they were taught until their archaic role in modern American police forces is put to sleep.

There are a handful of dispersed voices within academia and the legal system questioning the ethics and pragmatism of dogs working in a weaponized capacity. Some fairly high profile court cases questioning the viability of drug detection dogs as a tool of mass incarceration have led to a legal examination of whether or not drug detection dogs are acting upon racial bias from their handler, due to the Clever Hans Effect of unconscious cuing. But these voices are only blips in the sea of popular opinion, which extolls working dogs as selfless heroes. In the same vein, bite-and-hold dogs get a bit of a free pass because they’re often physically indistinguishable from dogs who are trained in unilaterally heroic pursuits, such as search and rescue or bomb detection. And although questioning police dogs in the courts and classrooms might lead to a broader conversation, we’re a very long way off from abolition.

So are White Dogs still a thing? Have weaponized dogs, after generations of intentional breeding as hegemonic tools, been threaded into the fabric of American dogs to the point where their own bias is inextinguishable? In the third act, Julie is jolted from her nonpartisan reverie when White Dog escapes the training facility and slaughters a black man on the altar of a church.

Unable to deny her culpability or the dog’s intentions any longer, her suggestion for euthanasia is decried by a dogged Keys:

Julie: He killed a man. In a church. And I’m sure it’s not the first black man he’s killed. Why didn’t you kill him?

Keys: I wanted to shoot him at the church.

J: Why didn’t you?

K: How I wanted to put a bullet in that son of a bitch!

J: Then why the hell didn’t you?

K: Because there’s still a chance to cure him.

J: Cure him? He just killed a man. There is no way you can cure that dog! I want you to shoot him now, before he kills more blacks!

K: So you finally joined the club. That club of horrified people who raise holy hell about that disease — that racist hate — but do absolutely nothing to stamp it out. That dog is the only weapon we have at least to remove a part of it! If I cure him.

J: If? “If” is not gonna stop him from killing people!

K: Yes, Julie. I can’t guarantee the result. But if I fail… I’ll get another white dog… and another, or another, or another, and another… and keep on working till I lick it. Because that’s the only way to stop sick people from breeding sick dogs. And goddamn it… I can’t experiment on a dead dog.

As a black American, I will continue to be tormented by the notion that I can somehow wield control over the oppressive system that I inhabit. Despite the innumerable generations of our nation’s stolen labor, stolen people, and stolen lands, the “if” is just too strong of a possibility to ignore. And so, while I know that I can’t rid the world of white dogs, I am driven to sacrifice my own sanity and safety to help change them.

Further reading: “You Should Give them Blacks to Eat”: Waging Inter-American Wars of Torture and Terror

Data Weighed

“I loved losing weight; I loved being more fit. I hate that the weight crept back. But it did, and anyone who would sneer at me for lack of willpower is welcome to walk a mile in my size-44 trousers. What I’ve been wrestling with now that I no longer quantify myself is why I don’t want to write the stories and take the pictures that made my diet blog compelling. I think it’s because it’s too detailed a mirror. I’m not in denial about the calories, or the snacking, or the judgments of the scale. I just don’t want to tell that story any more.”

— If you haven’t read this yet, read it.