New York City, October 5, 2015

★★★★ Light bounced off glass in great flooding sheets, glanced off the quilted side of a food cart to make twisting figures on the sidewalk. People were out in their drab chilly-weather clothes. It took some searching to find a warm spot of afternoon sunlight, and a cloud fairly quickly picked it off. The switch from foot socks to full socks was not enough for the office; a space heater had to be deployed under the desk. The Empire State Building stood side by side with the upside-down Empire State Building of negative space up Fifth Avenue, in the rich late-day glow. A man paused to take frame the sun-flooded pillars and arches atop the MacIntyre Building in his cameraphone.

The Night the Lights Went Out

by Casey N. Cep

I’ve been thinking a lot about murder. Not committing one, but a few of them from a few decades ago, so my playlists have become filled with murder ballads. Life has changed and so has death, but not murder; there might be less of it, but it’s still bullets and knives, bare hands, pillows and poisons. These ballads are as old as time, though you don’t hear that many of them on country radio any more. Threats and taunts, yes, but nothing quite like the murderous streak from my childhood: Garth Brooks, with a pistol fired at a cheating spouse in “The Thunder Rolls”; Gillian Welch, with a broken whiskey bottle to the neck of a rapist in “Caleb Meyer”; and the Dixie Chicks, with poisoned black-eyed peas down the hatch of an abusive husband in “Goodbye Earl.”

On the top of that heap of bodies was, and always will be, Reba McEntire’s “The Night the Lights Went Out in Georgia.” I say it’s hers, but she didn’t write it (that was Bobby Russell) and she wasn’t even the first to put the song on the charts (that was Vicki Lawrence). Firsts don’t matter, though, because that lightless night in Georgia has belonged to Reba ever since she streaked wrinkles around her eyes and fixed a dusty white wig on her head, playing the lead in one of country’s best music videos.

It’s one of the sappiest, soggiest things you’ll ever see: an elderly murderess confessing it all to a feckless journalist. The turtle-necked gumshoe is somewhere between Emily Bronte’s Mr. Lockwood and Anne Rice’s Daniel Molloy. He barely blinks, but removes his bottle glasses for dramatic effect as he says things like: “So… he killed them both out of jealousy?” “Let me see if I got this straight: Your brother…pleaded guilty…to protect you?” “And the judge didn’t want to hear the truth…because of his involvement…with your brother’s wife?” The lights may have gone dark in the song, but in the video they’re thousand-watt bulbs burning bright. Nothing is left to the imagination, and most of the plot flashes bold across the screen as newspaper headlines.

Just over four minutes long, the song’s an encyclopedia of southern gothic tropes: cheating spouses, crooked judges, backwoods lawyers, big-bellied sheriffs, and make-believe trials. It somehow manages to argue against capital punishment, for vigilantism, and against adultery with a short refrain seaming it all together: “That’s the night the lights went out in Georgia. That’s the night that they hung an innocent man.” It’s the innocent man’s sister singing this sad song, saying how sorry she is her brother went to the gallows for murders she herself committed, but insisting how not sorry she is that the body of his cheatin’ wife won’t ever be found.

“The Night the Lights Went Out in Georgia” might never explain why the singer hid one body and not the other, or just how a crooked judge managed to have an innocent man executed in time to get home for supper, but it doesn’t have to. That’s just the way that murder ballads are. Whether it’s “Knoxville Girl” or “Banks of the Ohio,” these songs haunt with the flimsiest of facts. They are filled with arbitrary, but affecting details: boys named Willie, veils long and black, chicks named Nellie Bly, and sheriffs from Thomasville. Just specific enough to crouch in the mind’s corners, murder ballads all shuffle the same motives and means while varying a few specifics.

Not quite Colonel Mustard in the library with a lead pipe, “The Night the Lights Went Out in Georgia” features an inherited gun and a hangman’s rope, but also the strange specificity of the singer’s brother coming home from somewhere called Candletop, stopping for a drink at a bar named Web’s, having his best friend Andy Wo-Lo reveal he’s a cuckold a few times over, including by one Seth Amos. Doesn’t matter if you can’t find Candletop on a map or have never in your life heard a name like Wo-Lo, the song’s charm comes from every one of those proper nouns.

Country Time is an occasional column about country music.

What TV Does To Itself

Here is an excellent piece by Emily Nussbaum about “what advertising does to TV” at a time when the two are necessarily clutching each other closer and closer:

Viewers have little control over how any show gets made; TV writers and directors have only a bit more — their roles mingle creativity and management in a way that’s designed to create confusion. Even the experts lack expertise, these days. But I wonder if there’s a way for us to be less comfortable as consumers, to imagine ourselves as the partners not of the advertisers but of the artists — to crave purity, naïve as that may sound. I miss “Mad Men,” that nostalgic meditation on nostalgia. But embedded in its vision was the notion that television writing and copywriting are and should be mirrors, twins. Our comfort with being sold to may look like savvy, but it feels like innocence. There’s something to be said for the emotions that Trow tapped into, disgust and outrage and betrayal — emotions that can be embarrassing but are useful when we’re faced with something ugly.

This is a call to action, almost, but perhaps it’s better read as a eulogy, or as content-creator self-care. “To be less comfortable” with a brand as character or a product as plot is only an option when the two are somehow at odds — if not in practice, then somehow in spirit. And as easy as it is to dismiss the craven CONTENT IS CONTENT people, who are not so much making arguments as they are stating what needs to be true for their businesses or industries to thrive, it’s not clear what we’re really aiming for here. Where is the threshold for an honest transaction between artist and patron and corporation? Surely what animates an argument like this isn’t passion for a particular kind of limited commercial, or for the importance of whatever line product placement allegedly crosses. “Those of us who love TV have won the war” is a statement dependent on what the war was about. To give TV the credit it deserves? For what? For imitating forms politely regarded as less crass or commercial, only to be consumed, shortly, by one considered by the same people to be the crassest of all?

From earlier in the piece:

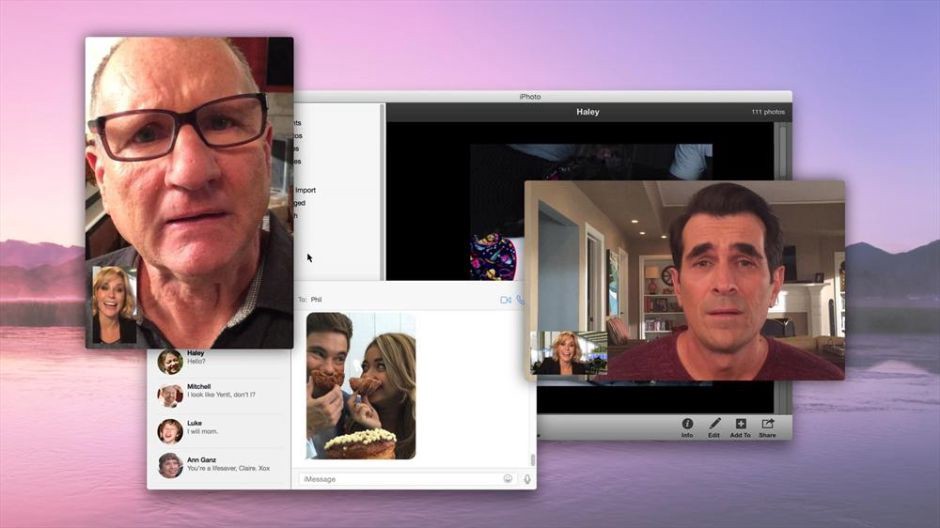

Product integration is a small slice of the advertising budget, but it can take on outsized symbolic importance, as the watermark of a sponsor’s power to alter the story — and it is often impossible to tell whether the mention is paid or not. “The Mindy Project” celebrates Tinder. An episode of “Modern Family” takes place on iPods and iPhones. On the ABC Family drama “The Fosters,” one of the main characters, a vice-principal, talks eagerly about the tablets her school is buying. “Wow, it’s so light!” she says, calling the product by its full name, the “Kindle Paperwhite e-reader,” and listing its useful features. On last year’s most charming début drama, the CW’s “Jane the Virgin,” characters make trips to Target, carry Target bags, and prominently display the logo.

Now, regarding that Modern Family episode, a Qz post from earlier this year:

FaceTime, Messaging, Safari, iTunes, Reminders, iPhoto and even the iCloud all make appearances at one time or another, but non-Apple apps like Facebook, Instagram and Google also get some screen time. The result is an episode that’s incredibly effective and very funny, without ever actually seeming like an ad. In part, that’s because — surprise! — Apple didn’t pay a cent to be involved.

We also learn that a previous episode, which revolved around the acquisition of an iPad, was uncompensated as well. Product placement wasn’t even necessary; but permission was. “Show producers sought out and received Apple’s blessing,” the piece notes. Its headline, presumably not compensated:

Modern Family’s’ Apple-centric episode is product integration at its best — and great TV

Where does a discussion about sanctity or truth or firewalls or checks and balances start, here, concerning this show about a happy family that loves Apple products? (A show you can watch soon after airing on iTunes, or on the Hulu app in your iPhone, iPad or Apple TV, which is available NOW in the Apple iOS App Store — please rate, thank you.)

What is a critic even supposed to ask for? And on behalf of whom? And maybe that’s what the piece is about, ultimately: still not knowing, even during the twilight of an industry, when things should be clearest.

Basic Soul Unit, "The Rift Between"

I rather like this. Perhaps you will too. The whole thing seems like a good soundtrack for a long walk, so if you’ve got something like that in your future click on the “Resident Advisor” bit at the top for the rest of it. I mean, if you are someone who owns one of those fancy phones that has a little computer in it that you can carry along with you on your journeys. Have I told you yet about how I still don’t have a smartphone? I haven’t? I must not know you personally, because oh my God everyone in my life is sick to death of hearing about WHY WOULD I WANT TO LUG THE INTERNET AROUND WITH ME ALL THE TIME / HOW GROSS IS IT THAT YOU CAN’T EVER BE DISCONNECTED FROM THE CENTRAL DISTRIBUTION POINT OF ALL THAT IS TERRIBLE ABOUT MODERN LIVING / DO YOU EVEN REMEMBER THE LAST TIME YOU HAD A THOUGHT ON YOUR OWN OR HEARD THE SOUND OF YOUR OWN VOICE INSIDE YOUR HEAD PROBABLY NOT / YOU HAVE NO IDEA HOW MUCH BETTER LIFE IS NOT HAVING TO LOOK ANY ANYONE ELSE’S PICTURES ON INSTAGRAM etc. It gets pretty tiresome even for me, and there are very few things about which I can’t be tiresome on a professional level, but I have so little left to be smug over in my life that I want to wring out every last drop of superiority that I can before they stop making phones that don’t connect you to the Internet and I become a glass-eyed scroll jockey like the rest of you. Wait, where were we? Oh, right, this track. I know nothing about the act in question but as I said before you got me distracted by the subject of smartphones, I rather like the song. Perhaps you will too. Enjoy!

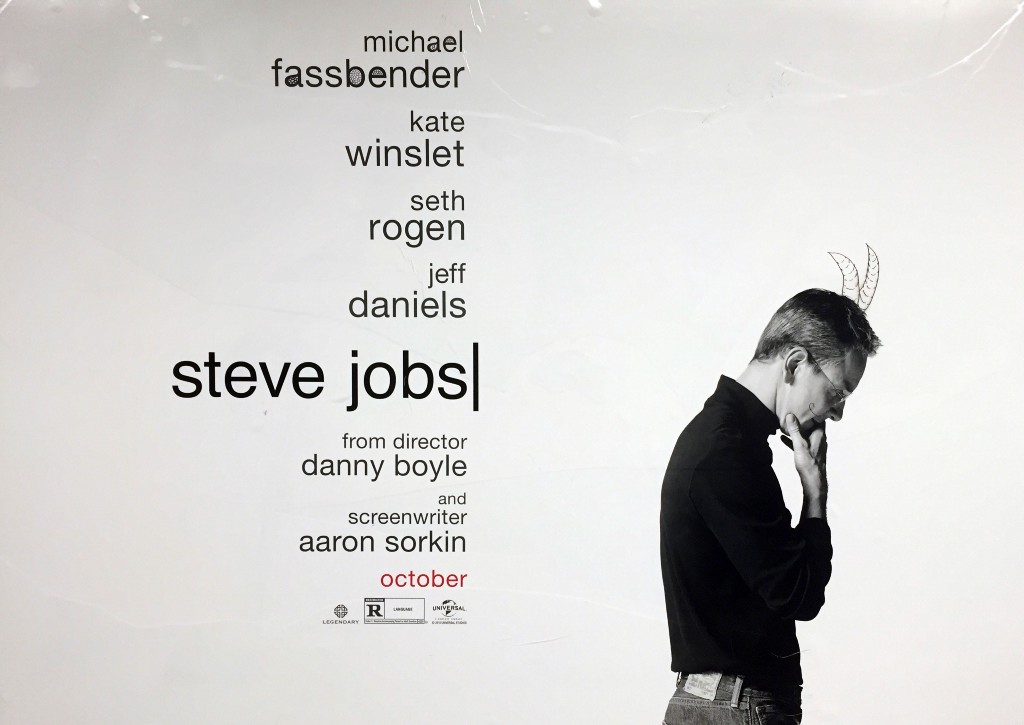

The 'Real' Steve Jobs

Steve Jobs is a three-act play written by Aaron Sorkin and directed by Danny Boyle, whose facts, such as they are, largely come from Walter Isaacson’s authorized biography of the same name. It is a superbly acted drama, but by far the most dramatic thing about it will be the internet’s reaction when it goes into wide release on October 23rd, because Steve Jobs is less about a product visionary than it is about a deadbeat dad who denies fathering his daughter, grudgingly accepts some culpability in her existence after reaching a low point in his career, then finally achieves resolution with her, which allows him to go on to do some truly great capitalism. All the while, this man is nagged by some haters while preparing PowerPoint presentations to announce some immaculately designed new computers, two of which, according to the film, are total failures.

If there are only two ways to portray Steve Jobs — as a visionary genius whose flaws weren’t really flaws because they were necessary to the practice of his genius, or as a deeply flawed megalomaniac who happened to be a visionary genius (maybe???) — Steve Jobs takes his genius for granted, if only to settle on the latter interpretation. This is the core of why people devoted to his company, his products, and their personal interpretation of his ethos will find Sorkin and Boyle’s film to be deeply offensive — because it inverts their preferred narrative of Steve Jobs and What He Means. (It will be especially offensive to those who, in an attempt to touch Jobs, have patterned themselves after him and decided that they are design or business mavens whose gift to the world is their extraordinary taste; it will feel like a personal attack on their entire mode of being.) To the extent that internet outrage manifests, it will be directly proportional to the success of this movie and its ability to concretize certain elements of Jobs’s public image through the virtuosity of Michael Fassbender’s performance, which is animated less by the man than the icon*.

The structure of the film is aggressively straightforward: It portrays in real-time(ish) a fictionalized account of the moments leading up to the launch events of the Macintosh in 1984 (Act I), the NeXT Computer in 1988 (Act 2), and the iMac in 1998 (Act III). As the film attempts to cram a redemption narrative, a complicated web of interpersonal relations, and more than twenty years of history into a series of backstage scenes at marketing events, it bends time and space greatly to produce an “impressionistic portrait” of Jobs. As Danny Boyle told the Wall Street Journal, “The truth is not necessarily in the facts, it’s in the feel.” And it does seem to feel… right, in many ways? Still, some of the odder results of the time warp include Jobs being aged several years, his hair grayed and his body slimmed down and slipped into his uniform of an Issey Miyake black mock turtleneck and Levi’s 501s at the 1998 iMac launch, the film’s climax, two years ahead of the onstage debut of the personal uniform he wore professionally for the rest of his life*.

Steve Jobs bends people too, but its attempted rehabilitation of former Apple CEO John Sculley, mostly known as the man who forced Steve Jobs out of Apple and led the company down the path that nearly killed it, will probably be called out the hardest. Steve Jobs shoves a backbone up Steve Wozniak’s backside as well — mostly, one suspects, because Seth Rogen can only play one part, which is Seth Rogen — so that he can ask the questions that every Jobs doubter poses: “You’re not an engineer, you’re not a designer… so how come, ten times in a day, I read, ‘Steve Jobs is a genius’? What do you do?” Who’s going to be so mad about that, especially since it has Steve Wozniak’s approval? (Never mind the uneasy parallel between the film, where Jobs suggests that Woz’s public criticism of him was a result of being manipulated, and that in real life, Woz offered his approval of the movie after being paid two hundred thousand dollars.) One can only imagine how the nerds will perceive Kate Winslet as Jobs’s longtime colleague Joanna Hoffman, who functions in the film as Jobs’s consigliere and conscience (and who appears at the iMac launch in the film, even though IRL she had retired by then).

But it cannot be over-stated how much screenwriter Aaron Sorkin is not exaggerating when he says that Lisa Brennan-Jobs is “the heroine of the movie.” For all of the people who show up at product launch after product launch after product launch to dutifully move their story forward — never forget the Apple II! — or to spout an endless stream of Sorkin-tuned quips at Jobs, the film pivots around his relationship with his daughter Lisa, which veers from inhumane to endearingly awkward, and which becomes thoroughly entwined with Jobs’s success as a businesshuman; consumerism abhors deadbeat dads.

It will no doubt be pointed out that while Jobs initially attempted to abandon his first daughter — who, the film did not make clear, did eventually take his name and come to live with him — he was devoted to the family he designed with his second wife, Laurene Powell Jobs, who apparently worked to derail the film, a fact that will be taken on its face to mean that the film is necessarily bad. The messaging to pre-empt the movie on this front has already begun: While Tim Cook’s letter to Apple employees on the third anniversary of Jobs’s death mentions only products and vision, the one released yesterday, for the fourth anniversary, pointedly mentions his family twice:

Steve was a brilliant person, and his priorities were very simple. He loved his family above all, he loved Apple, and he loved the people with whom he worked so closely and achieved so much…. He told me several times in his final years that he hoped to live long enough to see some of the milestones in his children’s lives. I was in his office over the summer with Laurene and their youngest daughter. Messages and drawings from his kids to their father are still there on Steve’s whiteboard.

What will get not a little lost amongst the people who care, above all, about fidelity to their vision of Steve Jobs, is that Steve Jobs is on its own merits, a self-consciously weird movie that goes to extraordinarily lengths to avoid being a generically shaped biopic (and yet…), and that maybe its clearly tenuous connection to reality truly is tangential, and that it will not change the already largely fixed iconography of Jobs, who has been beatified as a tyrant saint in boardrooms throughout corporate America and Silicon Valley, even if it manages to remind people that for a portion of his life he, like most men, was a terrible father.

Photo of poster grafitti taken in an NYC subway station

*Given the attitude toward Isaacson’s book in the Apple community (that it fails to capture the Real Steve Jobs, which is to say, the Good Steve Jobs), it is worth pausing to note Andy Hertzfeld’s take on the book: “Steve Jobs got the biography that he wanted and deserved: a best selling, well written, unbiased, comprehensive account of his life and work by the biographer of Einstein and Franklin. As much as he valued simplicity, Steve was a complicated man, full of contradictions, so there’s plenty of room for many different takes on his life and legacy.” I do think it’s fair to say, however, that separate from the issue of whether he properly recorded Steve Jobs’s life, Isaacson didn’t fully grok his subject.

*Although he wore the uniform in Newsweek that year, he wore a suit again when introducing iMovie in late 1999, before wearing the uniform onstage at Macworld San Francisco in January 2000.

New York City, October 4, 2015

★★★★ The light through the blinds gave cause for hope, even as the clouds were still there. People were out on the roof deck of the new building, bundled up in dark clothes, hurrying past the now-bare frames of the lounge furniture where sunbathers had lingered a month ago. The clouds broke apart to show a sky the blue of nice stationery and drifted southward. Straight-line light traced the straight lines of roofs. Blooms of reflected glow not seen in days returned. The iron planting-bed grate that had tipped up by a fallen tree had been put back in place, with an empty circle where the tree had grown. The children were zipped into their hoodies. In the night, slow ripples on the pool at Lincoln Center gently jumbled the reflections of the colored theater signs.

Welcome to Media Layoff Season

by The Awl

It’s our least favorite time of year: media layoff season. And thanks to El Niño, the cyclical contraction of capital in publishing every few years, it’s going to especially brutal this year at newspapers and magazines.

Bloomberg layoffs began last month, which aimed to slice off a hundred or so employees. No one would be surprised if more follow as Michael Bloomberg continues to dismantle any hope of a post-terminal future for his company.

The Boston Globe’s Boston.com suffered cuts last month.

Nylon just lost a third of its staff.

The Philadelphia City Paper is being shut down on Thursday by Broad Street Media; its staff is being laid off and its archive potentially wiped from the internet.

At Condé Nast, we have heard that the optimizers hired by David Geithner are looking to create efficiencies worth tens of millions of dollars. How many fewer jobs is that? We don’t know, but if you do, let us know. (It is also probably worth remarking that Condé, like many corporations, has learned to blunt the edge on big layoffs by slowly and continuously laying people off, two or three or four per a publication at a time, throughout the year, as it has done at GQ, amongst others. And then there’s Lucky.)

ESPN is rumored to be laying off “‘200 to 300’ employees in the coming months.”

The New York Daily News was thoroughly gutted the other week.

Despite executive editor Dean Baquet’s triumphant note to readers today that “many news organizations, facing competition from digital outlets, have sharply reduced the size of their newsrooms and their investment in news gathering” — which, we’re about a year from last year’s announcement of a 7.5 percent reduction in newsroom staff — some New York Times staffers are convinced that layoffs, if tiny ones, are coming soon. (To Baquet’s credit, the Times does have a knack for initiating layoffs without actually cutting down its headcount.) Maybe these staffers are just shell-shocked and paranoid — for good reason, just look at that revenue chart — but who knows???

The LA Times is gearing up for a loss of up to a hundred newsroom employees, along with ten to twenty percent of its total staff. Given the turmoil at the home office and its focus on centralization, it would not be surprising if other Tribune papers were also hit with layoffs. (Update: The layoffs start this week.)

There were fears of layoffs before Time Inc.’s move downtown, in part because it was revealed that it can cut up to a third of its staff without losing millions in job retention grants. The move to open-office hell of Brookfield Place has begun, and it was profitable in its most recent quarter without notable layoffs, so maybe it’ll be spared? (Then again, it had a rough year already, so.) There’s always next season.

Elsewhere, the Wall Street Journal did its culling over the summer, as did Meredith and Rolling Stone

. And at Hearst, where the magazines are in a constant, never-ending state of reorganization and consolidation, who could possibly tell if layoffs have happened, are happening, or might happen, except that it certainly seems like a lot of people aren’t around anymore?

Plenty of jobs at Vox, though.

Photo by Pat Castaldo

Obviously some of this is rumor and speculation (which we hope is wrong); corrections, more precise figures, a heads up about layoffs coming to a newsroom near you, and more welcome. Anonymity, if you want it, guaranteed.

Eric Prydz, "Opus (Four Tet Remix)"

This went up late Friday afternoon but I had a sense that we would need it more come Monday morning and lo, that turned out to be the case. This week, like the week before it and all weeks ever after from here on out until the meteor finally comes crashing into our lives, is going to suck, but there’s nothing that says you can’t start it off pretending that it won’t be the case. Perhaps this terrific track (it gets a little draggy in the middle but then so do I) will help. Enjoy.

New York City, October 1, 2015

★ Lights were on in apartment windows in the daytime. The floor lamp in the living room was still having an effect. It was certainly time to get out the hoodies; some children had gone all the way to puffy jackets. The jeans, air-dried and put away on some damp spring day, were a little musty, though there was no hope of rewashing and re-drying them anytime soon. The day darkened, not in any eerie or tropical way; little clouds moved under the rumpled cloud ceiling. Cold drops of rain began blowing. Night came on fast.

Drink the Brand

Although the big three soda companies all sell bottled water, they are not that excited about the trend. Bottled water is a less reliable line of business for them. Single-serving bottles of water, like Aquafina from PepsiCo and Dasani from Coca-Cola, earn margins similar to those of soda, but customers appear to have less brand loyalty to water brands than to Coke or Pepsi. It’s harder for the companies to compete in the grocery store, where low-margin companies that specialize in water are able to price large multipacks much lower than the soda bottlers want to sell them.

Generally, these companies worry about holding on to customers. The companies are expanding sales overseas, which has helped buoy their stock performance over the period. But in the United States, they all worry about losing even nontraditional drink sales to a competitor. Someone might be a die-hard Coke fan, but prefer Snapple iced tea to Honest Tea, which is a Coca-Cola brand.

It’s almost as if the Soda Brands are anxious about the power of their less established brands to compel consumption of a commodity product in this, the Year of Our Brand 2015. Not unlike some other industry right now! Hmm.

Photo by Daniel Orth