Love Communicated

“The early iterations of Smart Reply were overly affectionate. ‘I love you’ was the machine’s most common suggested response. This was a touch awkward: because the model has no knowledge of the relationship between an e-mail’s sender and its receiver, it provides the same suggested responses whether you are corresponding with your boss or a long-lost sibling. “The team was really puzzled about this,” Gawley said. ‘It turns out that our internal testers are very affectionate and that I love you is a very common thing for people at Google to say.’”

We Need a Part-Time Bookkeeper

by The Awl

A small and independent internet media company (okay, it’s us) requires a part-time bookkeeper, probably one to two days each month. (You’ll tell us!) Most work can be done remotely. The ability to meet monthly in our Downtown Brooklyn office is preferred but not necessary.

Responsibilities:

• Enter Accounts Receivable/Accounts Payable in Quickbooks Pro 2014

• Match bank deposits with client payments

• Assist sales team with collections and track receivables from issued invoices

• Monthly bank reconciliation

• Pay 1099 vendors via Bank of America Quickpay and PayPal on a monthly basis

• Consult with partners to time accounts payable with cash on hand

• Issue 1099s

• Develop and coordinate invoice tracking system with Publisher for online advertising sales

• Quarterly meeting with external accountant

Skills and experiences:

• Must have own computer with current quickbooks installed (file is currently QB Pro 2014)

• Expert Level Quickbooks, including import of banking transactions and journal entries

• Experience in a start-up and small business environment

• Working knowledge of Microsoft Excel and calculating formulas

• Familiarity with Google drive

• Experience coordinating information from multiple platforms

• Understanding of balance sheets and P&L;

• Must not embezzle

• Sense of humor.

Please send us a note about your work that includes your hourly rate requirement, as well as a formal resume and client references to legal@theawl.com. This listing was posted on December 10, 2015; we will note here if the role is filled. UPDATE: WE DID IT!!!

Oneohtrix Point Never, "5-5 Zebra2 (Indian Wells Rework)"

I’m not completely enamored with Oneohtrix Point Never’s Garden of Delete just yet — there are too many harsh edges for a man of my placid demeanor — but this Indian Wells version buffs over all those spiky points to make something even I can appreciate. Plus, it works great with rain, which is what we’re going to get today. Enjoy.

New York City, November 8, 2015

★★★★★ The apartment and the subway were stuffy still, but outdoors was the clean, sane chill of November. The streets were quiet and bright. Sun flared high up off the glass skin of the luxury tower, and a while later it flared off whole the glazed surface of the white brick tower across the street. It was cold enough for making a meat sauce but fine enough out for going to get the ingredients. Best to stay on the sunny side of the avenue. A dog sniffed at the used records and books stacked at pee height, and had to be hurried along before it could stop at any of them. Every building had dignity; the newer control house at 72nd Street looked almost as respectable as the older one. The sun went down clear and round, unimpeded by cloud or building. Had there been a cloud at all, all day? The four-year-old’s dark hair, where it stuck above the back of the couch by the window, lit up like new copper wire.

Automation for the People

One could fret over his or her inherent job security after reading a new McKinsey report, “Four fundamentals of workplace automation,” which deduces that “that 45 percent of work activities could be automated using already demonstrated technology” — though if “the technologies that process and ‘understand’ natural language were to reach the median level of human performance, an additional 13 percent of work activities in the US economy could be automated” — and that “60 percent of occupations could have 30 percent or more of their constituent activities automated.”

Or, faced with the knowledge that “automation technology can already match, or even exceed, the median level of human performance required,” proceed straight to the idea that when most of your job is automated, if you are one the lucky ones who manages to keep it to perform the remaining tasks that cannot yet be granted to a machine, all that free time will allow you to reckon not just how pointless it all was anyway, but to consider the marvelous and creative and feeling person that you truly are:

While these findings might be lamented as reflecting the impoverished nature of our work lives, they also suggest the potential to generate a greater amount of meaningful work. This could occur as automation replaces more routine or repetitive tasks, allowing employees to focus more on tasks that utilize creativity and emotion.

In the future, when the body and mind are no longer sufficient for the purposes of the production of capital, emotional labor is the only labor we will have left.

Photo by Jessica Merz

Cubenx, "Phase Rotation"

If you stayed off the Internet this weekend you deserve a Nobel Prize in the field of Being a Fucking Genius. What a nightmare the whole goddamn thing has become, right? Now, yes, I realize I have developed something of a reputation for being a bit of a downer, the kind of person who can only see the negative side of life, so I took some time yesterday to delve deeply into my psyche and discover why I’m so frequently discouraged with the way the web has played out. After all, there are tons of people out there to tell you that things are terrific, they’ve never been better, there’s nothing but blue skies ahead. Not all of them can be completely self-delusional or trying to sell you something, can they? Some of them must, in spite of all the evidence to the contrary, believe it to be true. And yet I remain unpersuaded. Is this false nostalgia on my part? The bitterness of a man growing older who pines for the seemingly sunnier days of his youth? No. I wasn’t exactly in love with life back then either. So, after careful consideration, here is what I have concluded: It’s not that things used to be so much better, it’s that everything is getting so much worse. Also, there are fewer places to hide now. You used to have to make an effort to realize just how awful it all is; now they ring your doorbell, shove it straight at you and then put up a picture of you with it smashed all over your face and expect you to like and share it. And you do. Really, it’s all your fault. Anyway, if you have to be on the Internet — and you hate yourself, so you do — at least there’s music. Why, here’s some now! Enjoy.

New York City, November 5, 2015

★ The river was lost in a dirty gray blur, inseparable from the lowest level of clouds. Higher up, for a while, the gray was feathered over silvery white and blue; a perfect white paw print floated in a clear patch. The preschool teacher was passing out plastic bags and matching floppy hats for a leaf-gathering excursion to the Park. A man pedaled around a corner on a Citi Bike, the tail of the jacket of his suit flipping up to reveal a red lining. The river faded into view then out as the warm murk thinned and thickened. The sky became full gray, with occasional drizzle. Cooking smells or cigarette smoke stuck to the wet air coming through the windows. A few spots in the west glowed pink, then returned to colorlessness.

The Guilded Age

1. The seal is broken on the “sharing economy.” There is a chance we can roll back that name; the collection of things it represents, however, is sticking around in some form. Uber has steamrolled through municipality after municipality. Airbnb Head of Global Policy Chris Lehane, at a press conference following the defeat of Proposition F, a ballot measure that would have more stringently regulated Airbnb-style rentals in San Francisco, described this change as emblematic of “a broader evolution in capitalism.” He’s probably right. Airbnb’s pitch, that your home is not just a place you live but an underutilized asset, represents a kind of systemic creep that’s hard to reverse. In the coming years, with or without interruption, various Uber-fors will grow in size and influence.

2. It is already possible to imagine better versions of most of these services! Not better in the slightly-cheaper-immediate-competitor sense. Better as in more efficient, conceptually. Better in that they are involved with fewer pieces of the things they enable, requiring, or enabling, them to take less of a cut. Take this first round of companies as proofs of concept: Uber as a way to get a ride or get paid for giving one; Airbnb as a way to find a place to stay or to get money for letting people stay in your home. These companies brought their concepts to the masses by, essentially, taking care of all of the details. They function as exchanges, as vetting systems; they handle payment and, to some extent, customer service. Their role as middlemen is part of why they’re valuable. In the short and medium term, it’s something nobody else has. But in a world where a few of the things Uber offers — let’s say payments, or safety certifications, or ratings and reviews, or dispatching — become trivial or public or in some other way closer to universal, their role as middlemen starts to seem less necessary. If two people can pay each other in an above-board way as easily as they do with Uber without Uber’s help, or if rider and driver can find each other without Uber’s network, then the value of Uber as it works today is diminished. Who knows how this will happen. It will take a long time, probably! But services or systems that offer Uber-or-Airbnb-like abilities to rent time or space or cars or trips or whatever without a strong and assertive single intermediate party are at least plausible. Airbnb is centralized and substantial enough that undercutting it, or disintermediating it, will become a priority for the internet and the people who invest in it. (If I were a better scam artist this is where I would try to get you to invest in a brand new BLOCKCHAIN startup. Very secret. Ground floor. It’s like Uber for paying Ubers. Investments cash only please, thank you.)

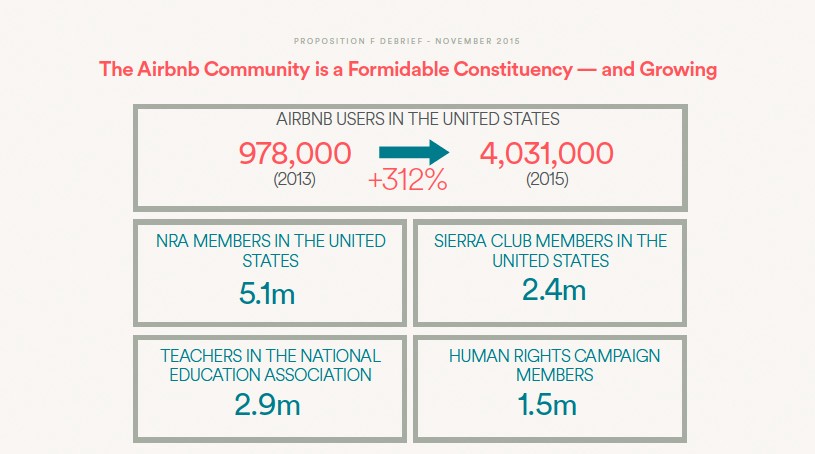

3. In the meantime, sharing economy companies must deal with more immediate issues. For example: A lot of the things they help people do are not quite legal. By extension, despite these companies’ best efforts to evade liability and pass it to their partners, some of the things they do are not quite legal. A lot of the things they help people do, as self-evident as these companies may think they are, are either not widely understood or are running up against some pushback. Some of this pushback comes from incumbent competitors, to whom the sharing economy companies represent a more efficient or cheaper competitor. So they’re trying to change the law; they’re trying to alter public opinion; they’re trying to win private and public battles in politics and public relations. They’re hiring the biggest-shot lawyers and PR people in the world. They’re also trying to mobilize their users, “partners,” and anyone else who’s using their various platforms. In Caroline O’Donovan’s characterization, Airbnb is “Building an Army.” According to her reporting:

A year ahead of the 2016 presidential election, Airbnb is launching a global campaign to unite its users and advocate for the company. Dubbed “100 Clubs” by the company, the initiative aims to network Airbnb users — hosts and guests — around the world into a series of guilds. The goal is to have 100 such clubs in major cities around the world by 2016, though Lehane said that figure was “more a floor than a ceiling.”

That these are called “guilds” speaks to just how strange and insincere the discussion around labor and the sharing economy already is. (Although maybe no more than the fact that we can’t seem to come up with anything stickier than the densely ideological term “sharing economy.”)

4. For Airbnb, this means that, much in the way that the Airbnb rental stock is both theirs and not theirs, depending on who’s asking and why, a mobilized platform/partner lobby is both theirs and not theirs, depending on who’s asking and why.

5. Uber’s regulatory battles will, to some extent, pave the way for other services, be they car-hailing apps or delivery networks or privatized replacements for public transit or just other types of on-demand labor whatevers. Airbnb’s will free up, to some extent, Airbnb competitors. But because they’re first, and because they’re huge, and because their investors have lots of adjacent interests, these regulatory battles belong to them. This means our next laws regarding how people drive and get driven, and the next sets of rules determining what and where a hotel can be, will be written largely by these companies. Or, at least, in the context of the specific battles these companies are fighting. Let’s say you don’t have any, or many, qualms about this “broader evolution” in capitalism and all the changes it may entail in our ideas about labor, ownership, and capital itself. Or just that you’re directly invested in it: you use or drive for Uber; you use or host on Airbnb. Your interests, in the near term, would obviously align with Uber’s and Airbnb’s! They’re fighting for your ability to use Uber and Airbnb. Of course you want that. You have demonstrated that you want that! These companies are fighting on your behalf in a real way. But they’re doing so as an unavoidable side effect of fighting for themselves. Airbnb in particular is comfortable speaking as a perfect representative of the concept it popularized, and the types of laws it would seek to defeat or enact would have to be somewhat well-aligned with the general idea of person-to-person nightly room rentals. But an ascendant Airbnb is different from a dominant Airbnb. An Uber battling with taxi companies is different from an Uber that has replaced taxi companies. These companies know this. Their leaders are CEOs and investors, not activists. Their interests will change, and not necessarily in parallel with the interests of their partners.

6. There is a vanishingly slim chance that, over time, Airbnb and Uber become less assertive with these partners, or with their users, or with governments. That would make them shitty companies! (To their investors, I mean.) Uber has been very clear that it doesn’t want to be just one of many Uber-like services. The dominant, victorious versions of these companies will be incentivized to do many of the things they criticize in the incumbents they’re replacing. As middlemen, they will extract greater tolls. They will find new sources or revenue and see opportunity in the thousands of asymmetric partnerships for which they set most of the terms. They will use their size to their advantage in every possible way. They will behave as incumbents behave; they will use their power to seek rent. I mean, maybe they won’t. But it would be an incredible rarity in the history of capitalism, evolved or otherwise! What happens when Airbnb starts, idk, giving people loans to buy homes to rent? Uber already does something like this!

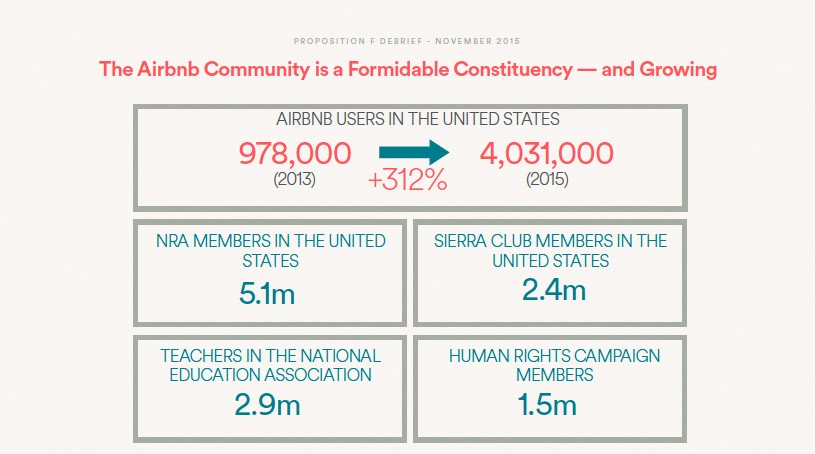

7. Assuming success for Airbnb and Uber casts political mobilization efforts in a different light. Here is one of the first slides in Airbnb’s post-Prop-F debrief presentation, published by Noah Kulwin at Re/Code:

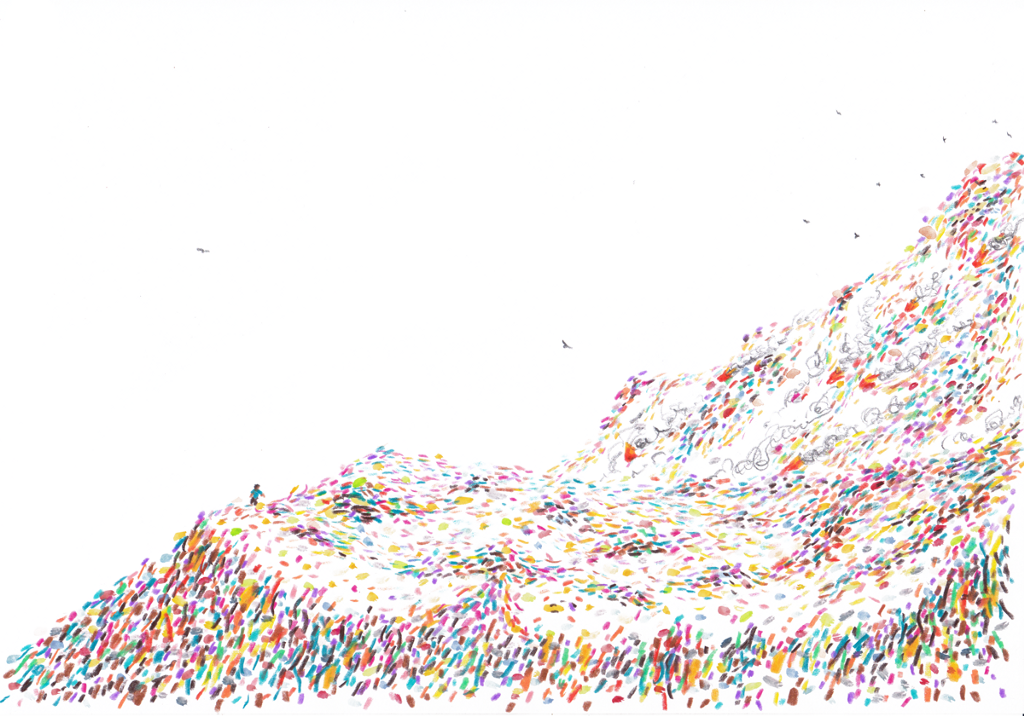

This characterization conflates Airbnb the company with the concept of apartment sharing. It is just barely visible: a helper, a lifeline. Certainly not an entire economic context! No way.

8. Airbnb is not a perfect representative of the libertarian vision of the sharing economy, in which Airbnb would be forced into instant and constant competition with unencumbered upstarts. Nor is it a perfect representative for the people who make money using its service, who are animated by a specific desire to keep making money from its service or services like it, and who would probably like to make more. It’s obviously not a good representative for people who are interested in neither of these things, but happen to live in a place and an economy that will be shaped by Airbnb. Airbnb is a perfect representative only for itself.

9. For a sharing economy booster, “guilds” in which renters collectively exert influence are probably worth organizing. It would be a subversive act, even! A recognition that, under a system like Airbnb’s, a home is different kind of asset, changing not just its place in the economy but yours. A guild, or union, would organize power not just against the cities and states, but against middlemen like Airbnb, which, if dominant, would set the terms of this new arrangement in almost state-like ways. That would be interesting, and perhaps help foster broader, healthier regulations that might moderate or prevent the types of excesses or abuses made tempting in a sharing economy at all points.

But that’s not what Airbnb’s “guilds” are meant to be. Airbnb’s guilds are a misleading concept to hide a new type of lobbying. (A type of lobbying which is characteristically ill-regulated.) A middleman-backed campaign, fake-guild-supported or not, would seek to eliminate regulation to clear the way for dominance over incumbents. When that is achieved, protective regulation might suddenly become Very Important And Totally Different By The Way. Whether or not a middleman company could coax its guild-things into rallying to support that depends on the nature of its competition: if these competitors offer partners a better deal, then maybe not; if they merely offer consumers a lower price, at the expense of a partner’s revenue share, then… maybe? Uber might be able to rally some drivers to campaign to preserve Uber as it works now. But what happens when the company starts lobbying for self-driving cars?

10. The political and legal fights over the sharing economy currently have three sides: the companies at the center; the incumbents they might be destroying; the governments that regulate their operation. The laws and norms resulting from this fight will reflect this. They will be some deviation from the average between the needs and desires and fears of one set of companies, another set of companies, and the government. There could, and should, be a fourth side, representing the people who make and/or spend money on these services. A sharing economy company might suggest that this fourth side is just the market. But then why try to co-opt hosts and users into this Airbnb-sanctioned guild system? What are they worried about? If everyone’s incentives are naturally and perpetually aligned, then won’t this take care of itself? Weird!! Related: the words “algorithmic labor union” are appearing together with increasing frequency.

11. An economy in which millions of jobs are replaced with on-demand labor, or in which more jobs are supplemented by on-demand labor, would change a lot of things. One thing it wouldn’t change is desire of these laborers to have some sort of leverage over their not-employer-employers, in cases where they feel under-compensated or aggrieved or abused. That such organizations may then be harder to form against amorphous contract middlemen will make these companies’ efforts to help their partners organize and mobilize morbidly funny.

12. Or maybe Airbnb is setting itself up for a headache? The Awl’s Tech Lord/Code Human Dusty Matthews made a good point in our work chat: “Seems a little dangerous to create regional ‘guilds’ in Airbnb.” That is: setting precedent for the type of host-to-host communication that could eventually become a liability.

13. The companies best positioned to make the most money from the early days of an “evolved” capitalism will play an important role in establishing how such an economy should function. Their successes and failures will make some people richer and others less rich. But the widespread success of sharing economy concepts will change a lot more than its leading companies’ fortunes. Airbnb founder Brian Chesky is already trying to get out in front of these changes, suggesting that his company helps “make ends meet, keeping people in the middle class.”

14. But this is a different middle class! (Also: Hm. What might be pushing San Francisco’s middle class out?) It’s a middle class in which owning a home might not be possible without also renting it out sometimes; in which your ownership of assets is contingent on your willingness to put them, and yourself, to work. This would be a profound change in the daily lives of many people. Hosting a few nights a month in order to keep your apartment is something we hear about people doing in expensive cities. It’s not a common behavior, really, and it’s certainly not a standard behavior. So it’s easy to think of a company like Airbnb, in that context, as a helpful facilitator. But what if their model becomes the norm? What if renting your apartment is just another item on the list of things you have to do to get it, right after “getting a terrible loan?” Then how will you think of Airbnb? What kind of relationship will hosts have with it? And what will they want?

When a company says it’s changing the world it can mean be interpreted three ways: as a statement, as an admission, and as a threat. That much, at least, is still up to you.

Gifs cut from a video by Harvard’s School of Engineering and Applied Sciences and the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering

Where Ships Go to Die

by Peter Wieben

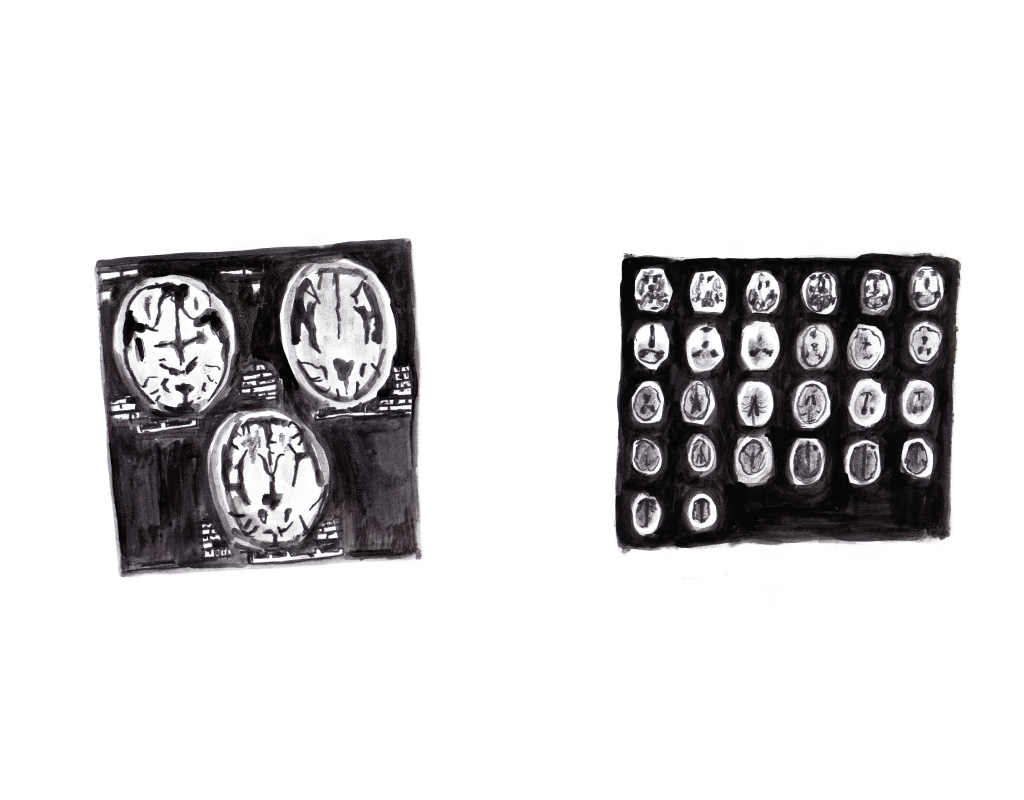

My friend Will makes industrial machines. A while ago, he moved to India to start a company. While driving one day, he had a stroke, and lost control of his vehicle. After being let out of the hospital, he emailed me and said that he wanted to show me the future of industrial civilization. A few months later, I flew from Cairo to Ahmedabad.

Scans of Will’s brain, following stroke.

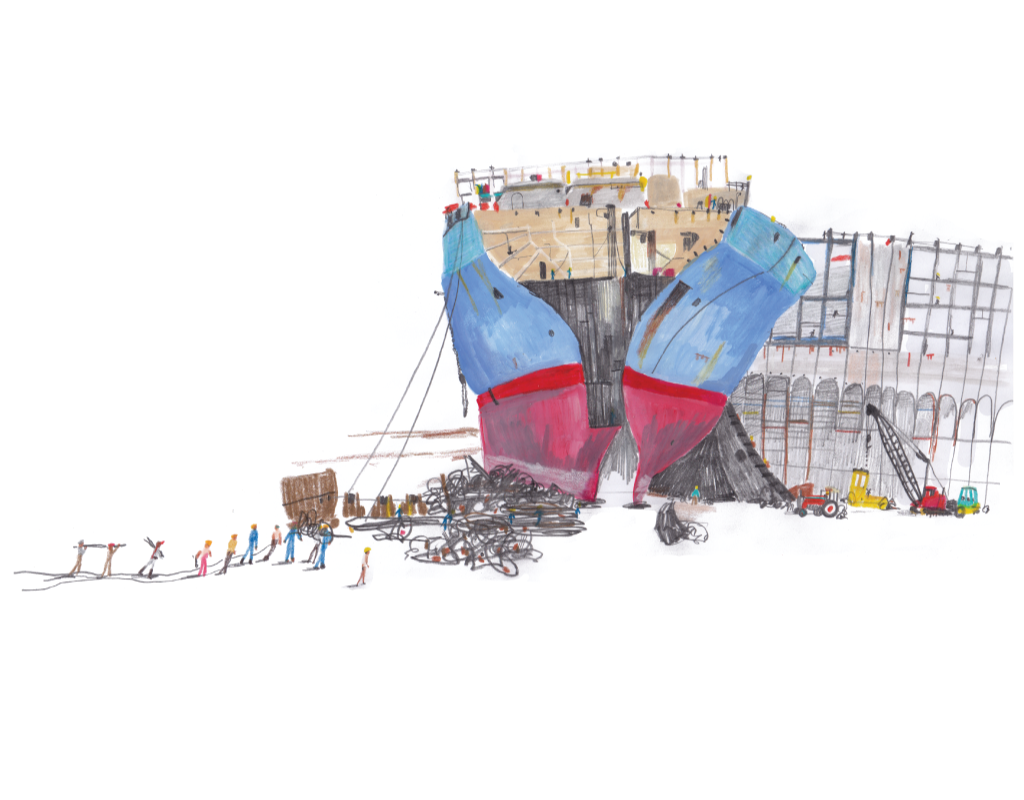

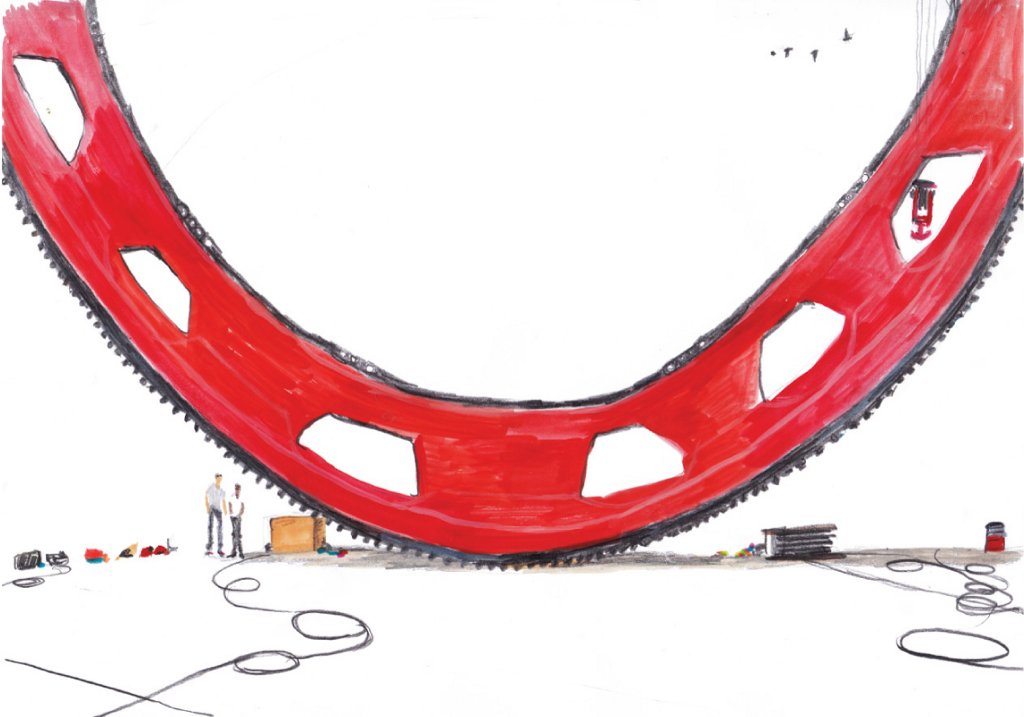

A little while into our journey, we decided to sneak into a shipyard at Alang. It’s a graveyard for ships — around half of all ships are sent there to die — where giant boats are torn apart with basic tools. We were told that it was usually not legal for anyone to go there who is not interested in buying scrap metal; too many foreigners had ventured there with the intention of exposing its labor and environmental practices. In order to get in, Will told someone that he was interested in buying scrap metal, and due to his machine-building background, he was very convincing.

The drive to Alang from Ahmedabad was very long. When you arrive, you drive through a huge flea market that sells anything that has been taken out of the ships. The ships are sold whole, so even the family photos of the sailors are sold off afterwards. There were warehouses full of lifejackets, treadmills, and blenders.

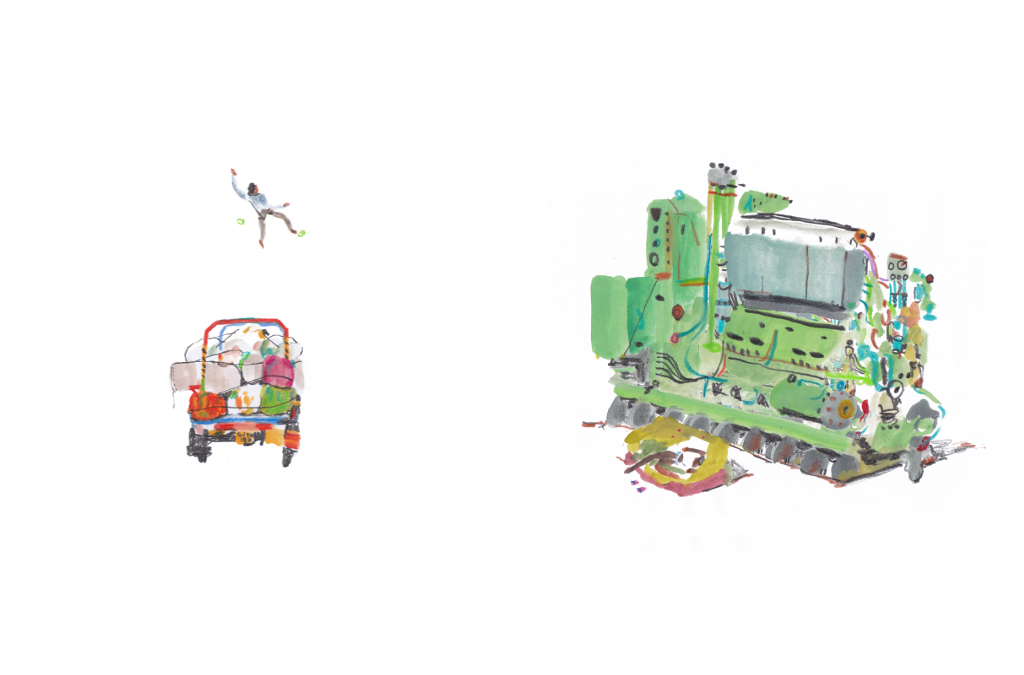

A man flies off the back of a potato truck and loses his shoes; a sick man is lying in the shade of an engine that was taken from a giant ship.

The shipyard smelled like a chemical fire. There were men crawling on piles of sharp metal, and machines tearing large pieces of metal apart. Everywhere we looked, men were engaged in Sisyphean tasks, surrounded by sparks and smoke. The ships went on for kilometers, one ship after the next; they were all so enormous that the little men on them look like fleas. While driving up and down the rows of ships, a dog attacked our car. It looked like it had been dipped in oil.

We asked a yard boss how many people die every year. He shrugged and said “four or five.” There were open fires burning insulation, and men climbing up through the guts of the ships. Most of the deaths, we assumed, were industrial accidents. Falling, crushing, burning. Others, due to inhalation, took longer and happened beyond the borders of the shipyard.

At the edge of the shipyards were open sewers and muddy workers’ quarters. The shacks were made of corrugated steel, and fifteen workers could stay in each one. All over Alang, there were hand-painted signs that said things like SAFETY IS OUR MOTTO or CLEAN ALANG GREEN ALANG.

The coastline at Alang, covered with oil, metal, feces, trash, shoes.

After leaving the shipyard, Will said he had another idea: Back in Ahmedabad, at the edge of the city, he said there was a mountain made entirely of trash. We left Alang, and went to look for it.

On the way, we kept getting sidetracked, looking into machine shops and pulling over to watch festivals. We went to a giant warehouse that is home to a five-axis CNC lathe, a very powerful machine capable of making machine parts; Will called it a “mother machine.” This is a gear that is part of a machine that digs down into the earth to mine materials used to make more machines.

A painting outside a small machine shop in Ahmedabad.

We found a large number of statues. These represent Lord Ganesha, Remover of Obstacles. (Will is in the middle, for scale.)

People walk up the stairs of a temple and float away forever; an abandoned letter.

We went to a festival for holi and saw a machine that could single-handedly make music for weddings. Included in the machine were drums, horns, xylophones and many gears.

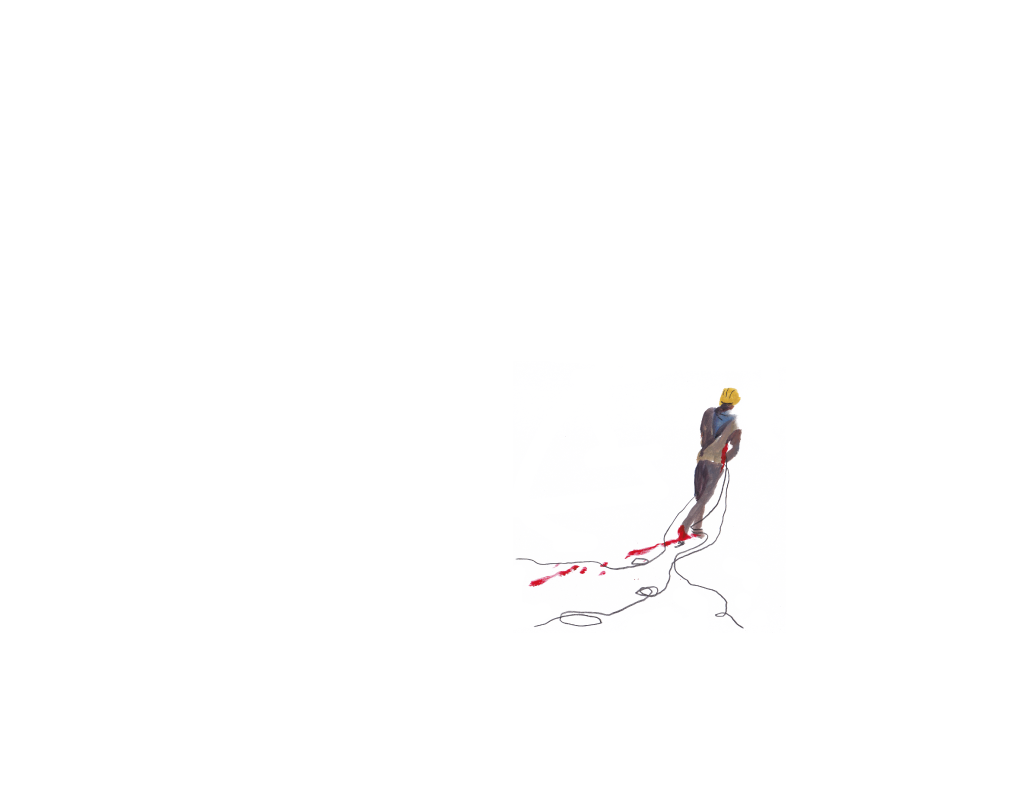

Street sweeper.

Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India.

I became obsessed with abandoned shoes. I saw them sitting everywhere. I took pictures every time I saw an abandoned shoe. The area we were in was very chaotic, and people were moving machines around and making a lot of noise, so I tried to concentrate on the abandoned shoes.

Near the end of the journey, we found what we were looking for, a looming shadow in one of the industrial districts of Ahmedabad. The mountain seemed to be ten stories high. Trucks constantly dump new trash into the pile, which smolders twenty-four hours a day. There are families that live on top of the pile in huts made of trash. All of the children were wearing mismatched shoes; on top of the mountain there were many, many abandoned shoes.

Will claimed that this could all be done in a way that was safe and clean, using robots. It would be efficient, cheap, free from suffering. In the end, he said, industrial civilization always only wanted more machines.

"If trees gave off Wi-Fi they'd be everywhere."

“A confession: it’s getting harder for me to read. Though I continue to carve out hours a day for it, it’s getting harder to carve out the corresponding mental space, the energy and concentration to focus on language and stories and ideas. The myriad things beeping, buzzing and flashing all around me have so habituated me that I now check on them when they’re silent to find out why they’re not beeping, buzzing and flashing. The other day, I overheard someone say, ‘If trees gave off Wi-Fi they’d be everywhere. Too bad they only give off oxygen.’ That about sums it up.”