New York City, December 20, 2015

★★★ Finally it was possible, if not strictly necessary, to try out the new parka. The sun was strong enough to feel warm where it landed, though the cold nipped through the socks over the top of the low sneakers. The bustling on the sidewalks and shops was energetic, not desperate. People were still bareheaded, coats not all zipped. The parka didn’t need zipping. The groceries could be toted in ungloved hands.

The Awl 2015 Gift Guide

by The Awl

Time is running out to buy holiday gifts! Here are some great items to buy, with The Awl’s Amazon affiliate code.

Need a good gift for your dad, your grad, your daughter, or your friend? How about a computer! Amazon Affiliate The Verge says the “MacBook” is the computer to buy. Amazon Affiliate The Wirecutter says the “MacBook” is the computer to buy. Amazon Affiliate The Awl agrees: The “MacBook” is the computer to buy! You can buy a “MacBook” using The Awl’s affiliate code by clicking here. Happy holidays!

Apple MacBook MJY32LL/A 12-Inch Laptop with Retina Display (Space Gray, 256 GB)

Need a good gift for your mom, your friend, your family member or your friend? How about a TV! Amazon Affiliate CNET says that the “VIZIO M65-C1 65-Inch 4K Ultra HD Smart LED TV (2015 Model)” is a good television to buy. Amazon Affiliate The Awl agrees: the “VIZIO M65-C1 65-Inch 4K Ultra HD Smart LED TV (2015 Model)” television sure sounds like a good TV to buy with The Awl’s affiliate code, which will result in a small commission being paid to us, by clicking here. Happy holidays!

VIZIO M65-C1 65-Inch 4K Ultra HD Smart LED TV (2015 Model)

Need a good gift for your son, your granddaughter, or your boss? How about a Bluetooth speaker! Amazon Affiliate TechCrunch says a good cheap wireless speaker is the “Anker Classic Portable Wireless Bluetooth Speaker.” Amazon Affiliate TechCrunch says a good, more expensive speaker is the “Bose SoundLink III.” Amazon Affiliate The Awl agrees on both counts: The “Anker Classic Portable Wireless Bluetooth Speaker” and “Bose SoundLink III” sound like good speakers to buy with The Awl’s affiliate code, which will result in a small commission being paid to us, as well as smaller commissions resulting from further purchases made during a short period following your initial Awl Affiliate session on Amazon. Happy holidays!

Bose SoundLink Bluetooth Speaker III

Need a good gift for an acquaintance, or closest living friend of a better but recently deceased companion? How about a coffee device! Amazon Affiliate Engadget recommends the affordable “Aeropress Coffee and Espresso Maker,” while Amazon Affiliate Slate recommends the “Chemex CM-1C 3-Cup Classic Series Glass Coffeemaker.” But Amazon Affiliate Business Insider and Amazon Affiliate The Verge both say that the more expensive “Cold Bruer Drip Coffee Maker B1” is good also. Amazon Affiliate The Awl says, “ok!” Both the “Aeropress Coffee and Espresso Maker” and “Cold Bruer Drop Coffee Maker B1” are good gifts to buy with The Awl’s affiliate code, which will result in a small commission being paid to us, as well as smaller commissions resulting from further purchases made during a short period following your initial Awl Affiliate session on Amazon, which is exactly the type of supplementary revenue stream that a largely advertising-based web publication is looking for at this exciting time online. Happy holidays!

Aeropress Coffee and Espresso Maker

Chemex CM-1C 3-Cup Classic Series Glass Coffeemaker

Cold Bruer Drip Coffee Maker B1

Need a good gift for someone who you can’t stop from buying a gift for you? How about a Star Wars Thing! Amazon Affiliate Bustle says that “Genuine Star Wars Luke Skywalker Adult Collectors Watch” is a good thing to buy. Amazon Affiliate io9 says that “Sony PlayStation 4 Limited Edition Star Wars Battlefront Console” is a good thing to buy. Amazon Affiliate The Awl does not disagree: “Luke Skywalker Watch” and “Sony PlayStation 4 Limited Edition Star Wars Battlefront Console” are good gifts to buy with The Awl’s affiliate code, which will result in a small commission being paid to us, as well as smaller commissions resulting from other purchases made during a short period following your initial Awl Affiliate session on Amazon, which is exactly the type of supplementary revenue stream that an advertising-based internet publication is looking for at this exciting time online, although some worry that escaping one major platform dependency by shifting to yet another asymmetric partnership is just delaying the inevitable. Happy holidays!

Genuine Star Wars Luke Skywalker Adult Collectors Watch

PlayStation 4 500GB Console — Star Wars Battlefront Limited Edition Bundle

Need a good gift for a human? How about an object! Amazon Affiliate Gizmodo and non-affiliate (???) publication Wired say that the “Amazon Echo” is a good object to buy. Amazon itself also says that the Amazon Echo is a good object to buy. Amazon Affiliate The Awl consents: The “Amazon Echo” is a good gift to buy with The Awl’s affiliate code, which will result in a small commission being paid to us, as well as smaller commissions resulting from further purchases made during a short period following your initial Awl Affiliate session on Amazon, which is exactly the type of supplementary revenue stream an advertising-based internet publication is looking for at this exciting time online, although some worry that escaping one major platform dependency by shifting to yet another asymmetric partnership is just delaying the inevitable. Others point out that, much like its willingness to temporarily forgo profit in favor of market domination, Amazon’s affiliate system does not seem like it would serve the interests of a further victorious and ubiquitous business. Happy holidays!

Need gift? Amazon! Amazon subscription good. Amazon Awl yes yes: Amazon good buy with Awl Amazon. Thank you. Thanks. Happy holidays!

Amazon Prime One Year Membership

Disclosure: The Awl is an Amazon Affiliate site and may receive a small commission on reader purchases.

Top photo by Kris Mouser-Brown

Save Yourself

by The Awl

The end is almost here. (Of 2015.) As we hurtle ever onward, we are constantly and emphatically told to never look back, or at the very least, to have no regrets. (YOLO, hakuna matata.) But this is wrong: Humans are perpetual regret machines.

The Awl’s 2015 year-end essays are about those machines: the things they made; the ways they could have been stopped. Pieces will be published daily until the year finally gives up. Contributions this year are from Carrie Frye, Rachel Monroe, Kevin Nguyen, Laura June, Lindsay Robertson, Bijan Stephen, Casey Johnston, Ryan Bradley, Rob Dubbin, Laur M. Jackson, Jia Tolentino, Jane Hu, Jenna Wortham, Emma Carmichael, Katie Notopoulos, Maria Bustillos, Paul Ford, Max Read, Leah Finnegan, Jazmine Hughes, Jacqui Shine, Rick Paulas, Helen Rosner, Dayna Evans, Bex Schwartz, Brian Feldman, Leah Reich, Johannah King-Slutzky, Jason Parham, Jo Livingstone, Matt Siegel, Silvia Killingsworth, Vinson Cunningham, Betsy Morais, Meghan McCarron, Cord Jefferson, Brendan O’Connor, and Maud Newton.

You can also find all the essays, as they are published, collected here:

Gifs from Imgur

Doomed

One Saturday morning this summer, I was sitting on my couch working on my book. It was early. The windows were open, and I could hear my neighbor and her toddler out in their yard playing and singing. Their voices drifted over in a burbly, companionable way, not too loud, not too soft: “If you’re happy and you know it, clap your hands (clap clap).”

My book’s a novel, and one thread is set in the late nineteenth-century Arctic. That morning I was reading about Robert Peary, the American who claimed to have reached the North Pole in 1909, the first to ever do so. (Peary rejected Frederick Cook’s claims that Cook was the one who made it there first, in 1908.) Now if they ever issued a series of nineteenth-century Polar explorer trading cards (snow-crusted beards, fur hats; think of the profits!) Peary’s card would be the card I least cared to keep. Short version: He was a dick. Still, I had been in a stir of sympathy for him all that week as I read the accounts of his different expeditions — five in all, the first one in 1886 — and sensed how, with each trip, he was growing increasingly desperate and haggard, feeling his chances at glory running out. On one expedition, undertaken when he was forty-two, he traveled for so long and through such intense cold that he lost eight toes to frostbite. EIGHT TOES! Only his little toes were left. He had his feet bandaged up, had his men strap him back to his sledge, and kept going. That is how badly Peary wanted to reach the North Pole.

There’s a part of my brain that can’t experience anything right now — reluctant admiration for a dead explorer, listening to a neighbor and her child playing (if you’re happy… clap clap), exhilarated feelings, sad stripped feelings, whatever — without an accompanying low scampering hum of “what of this can I use for the book, what of this can I use for the book.” I’ve been working on it for three years now, a long time. It’s been a largely good period — I’ve been engrossed, I know myself lucky. Still, it doesn’t escape me that I’ve grown shabby while working on it. The Arctic’s melted and melted some more. The little baby across the street has become a clapping toddler. Sometimes I’ve felt like the entire venture was a terrible, terrible mistake, but we’re — me and it — strapped together now and there’s no going back. Then I think, “Wow, maybe you can use that feeling for the book.”

If you’re frostbitten and you know it, amputate (thunk thunk).

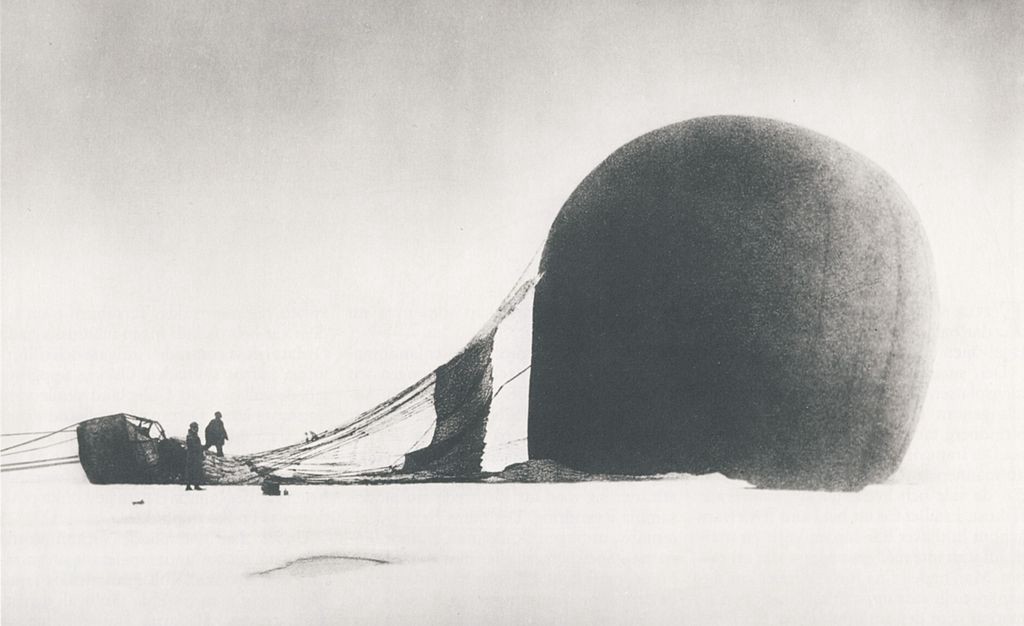

In 1897, a Swede named S.A. Andrée and two companions, Nils Strindberg and Knut Fraenkel, departed in a hydrogen balloon for the North Pole. Their plan went like this: Launch from a specially constructed hangar near Spitsbergen, in Norway; follow favorable air currents to the North Pole; drop a buoy over the pole (written in invisible ink on the side of the buoy: “Sweden waz here! In your face, Norway!”); then float on, possibly to the other side of the world. Maybe they’d descend in Siberia. Or Alaska. Or San Francisco. Who knew how far they might go! Andrée predicted that his balloon, the Eagle, might stay aloft as long as 30 days. As Alec Wilkinson writes in The Ice Balloon, his excellent account of their journey, Andrée packed a tuxedo for the trip, just in case.

The trip’s sponsors included Alfred Nobel and the King of Sweden. Their involvement gave the enterprise some of its air of viability. Andrée’s character also made the plan seem plausible (or plausible-ish). He was not — on the surface at least — either quixotic or romantic. He was an engineer. His day job was in the Stockholm patent office. (His balloon was a marvel of ingenuity and good mechanical design, with a special system of guide ropes and sails that would allow him to steer and a little stove that could be lowered twenty-five feet from the basket so that the men could cook without the balloon exploding.) He’d been to the Arctic once before, as part of Sweden’s delegation for the International Polar Year of 1882, and acquitted himself well there. He believed that hydrogen balloons specifically, and air travel more generally, offered a solution to a problem — how to reach the North Pole — that thus far sledges and ships hadn’t been able to solve.

The words “assured” and “calm” come up in many descriptions of him. Explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson wrote of him, “Andrée was tall, handsome, and modest. The world thought of him as young, although it could, when it wanted to justify its confidence in him, point to his forty-two years.” In the two portraits I’ve seen of him, his face looks as smooth and imperturbable as a balloon’s surface if a balloon ever had an enormous blond mustache.

The forces that drove him — that is, that made him a person fascinated by hot-air balloons and flight, someone who liked to float along the curve of the earth, free from all ties — went mostly un-verbalized, though they must have made themselves felt in person. You can hear some of this animating spark in his recollections of the man, John Wise, who first taught him about aeronautics. Wise had, Andrée wrote, made about four hundred flights in his long life:

He had flown [balloons] in sunshine, rain, snow, thunder showers and hurricanes. He had been stuck on chimneys, smoke stacks, lightning rods, and church spires, and he had been dragged through rivers, lakes, and over garden plots and forests primeval. … The old man himself, however, had always escaped unhurt and counted his experiences as proof of how safe the art of flying really was.

The Eagle’s departure in 1897 was something of a repeat performance. The summer before, the balloon had been brought to this same island near Spitsbergen, unpacked, and inflated with hydrogen. It was ready; the voyagers were ready; the international press was certainly ready. A favorable wind was not. Andrée needed a south wind, steady and not too strong. It never presented itself and the window of travel closed. The balloon was deflated, and Andrée had returned to his work in the patent office to await his next opportunity. Soon after, one of his two companions dropped out of the expedition, announcing in several public spots that he now believed the trip impossible.

In the meanwhile, the Norwegian explorer Fridtjof Nansen — feared dead after an absence of three years — had returned from the north: 1. not dead 2. with a new farthest-north record for Norway 3. still gloriously handsome and 4. with a giant sackful of heroic, amazing tales. (This is why the Nansen Polar explorer trading card is always the most popular. What can you do with a rival like that? The fucker was even a great writer.)

All of these incidents — the failed attempt of the year before, his friend’s defection, Nansen’s resurrection — would have been swirling around in the air at the 1897 launch. In Wilkinson’s description of those weeks, everyone sounds tense, snappish. I picture the scene as a few dozen mustached men — engineers, carpenters, journalists, etc. — slinking around the giant, wind-blown balloon house on the water, trying to not trip over ropes and getting in each other’s way as the tethered balloon rattled and rolled around like an impatient spirit. Each day everyone anxiously considered the weather. One day the wind was too blustery. On another, it came from the wrong direction. Finally a day came where conditions looked favorable. Still Andrée hesitated. Strindberg and Fraenkel grew openly impatient. Finally, he relented. They’d go.

It was July 11th. Farewells were made. The three aeronauts got into the basket. The final cables restraining the balloon were cut. The balloon rose. It knocked against something and Andrée was heard to say, “What was that?” Then they were off.

The spectators rushed outside and watched as the balloon dipped toward the water, touched against it, recovered and began to climb its way to the sky. To some of the observers it seemed impossible that it might clear the distant hills but it did.

In an hour, the balloon was nothing but a speck.

The three passengers were never seen alive again.

A brief sidetrack: I’m often struck/amused by how the accounts of Arctic journeys from this period can be seen as mirroring the stages of creative pursuit (minus the frostbite and scurvy). It begins with the person seizing on their plan in a burst of euphoria and optimism. Everything seems possible (“Why, I might even need this tuxedo when my balloon lands!”). This exhilaration is soon mingled with dread and panic. The explorer who has announced to enough people that he’s going to the North Pole will… eventually have to leave for the North Pole. The writer who has told her editor, “Sure, I’ll write that thing” finds… she has to write that thing.

The journey is embarked on. It’s found to be a hundred times more involved and awful than foreseen. Equipment is shed, loads are lightened. Proposed outlines jettisoned. And still the mountains that looked so close that morning end up being far, far away.

Elation gives way to trudging. Trudging gives way to despair.

Even Nansen — glorious, perfect Fridtjof Nansen — was not immune to this. From his book Farthest North: “Here I sit in the still winter night on the drifting ice-floe, and see only stars above me. … Thought follows thought — you pick the whole to pieces, and it seems so small — but high above all towers one form… Why did you take this voyage? … Could I do otherwise? Can the river arrest its course and run up hill? My plan has come to nothing.”

If you’re hungry and you know it, pemmican (chop chop).

The aeronauts’ first night aboard the Eagle was lovely. They skimmed along through the dark, over the clouds. Andrée’s journal entry makes him sound cold but content. When dawn came, the clouds had broken and he could see the surface beneath him. “The snow on the ice a light, dirty yellow across great expanses. The fur of the polar bear has the same colour.”

That day the balloon dropped down to the ice and bumped along the ground. Hydrogen balloons lose height in shadow and fog — fog now enclosed the Eagle. The men threw out whatever they could spare to lighten the load. The balloon didn’t rise but continued to scud along the ice. This eventually made Strindberg motion-sick, which gives a sense of how odd and concussive it must have felt. They continued this lurching, hiccupping progress over the next day. The party sent off carrier pigeons (thirty-six were on board) with messages of their progress. They ate chocolate biscuits and drank ale — this part doesn’t sound too horrible. Having risen in the air, they looked down and saw a polar bear swimming in a channel of water beneath them.

The balloon came down for good on July 14th.

As Wilkinson records in The Ice Balloon, the three had “made the longest flight ever, having been aloft for sixty-five hours and thirty-three minutes…” They’d traveled more than five hundred miles, but because of the zig-zagging of their path this put them “about 300 miles north of where they started, approximately 300 miles from the pole.”

Only one of the carrier pigeons made it back. The message gave their coordinates along with an “All well on board.” A couple buoys later turned up as well. But after 1900, nothing — no word, no Nansen-like return.

For decades the fate of Andrée and his companions was a great mystery. The men’s remains were eventually found, in 1930, in the lee of a cliff on White Island (now called Kvitøya). Strindberg’s body was buried in a cleft between two rocks, giving the impression he’d died first. Andrée’s body was propped against a rock, legs extended, in a pose that made him seem as if he were waiting. Fraenkel’s body lay nearby, frozen under deep ice. Polar bears had torn at both Andrée’s and Strindberg’s bodies.

Their final days are still mysterious in many ways. It’s not known how or exactly when they died. The most convincing theory I’ve seen was advanced by Stefasson in his 1938 book Unsolved Mysteries of the Arctic. He posits that Strindberg died in early October, after breaking through the ice while hunting a polar bear. Andrée and Fraenkel, he thinks, may have died soon after from asphyxiation when snow blocked the ventilation pipe of their cooking stove. But this is all conjecture. (Wilkinson gets more into the different theories here.)

Their journals, equipment and Strindberg’s rolls of film were found with the bodies. From these journals and photos it’s possible to piece together their journey across the ice to White Island.

After the balloon landed on the ice, they spent a week transferring its contents onto sledges. These sledges, once packed, weighed hundreds of pounds. The three then started walking back towards land and people, but choosing a route that would allow them to do some exploring along the way.

The ice in the Arctic isn’t smooth — it’s shaggy and ridged and filled with jagged, razor-y bits and hummocks and other obstacles to bark your shins against. There are pools of cold water to slip into (whoopsie-daisy!) as well as leads — or channels — in the ice to clamber across as you attempt to skip from floe to floe. In some places you might have to hack at the ice with an axe to make your way. In others, where the ice is new and thin, you might have to crawl, spreading your weight, so the ice won’t break beneath you.

All of this the men accomplished while also maneuvering sledges that weighed, basically, as much as upright pianos. And a boat! Sometimes they toiled like this for twelve hours a day. Andrée’s journal mentions the ice’s ceaseless “cracking, grinding and din.” It was always churning, night and day, and as the men walked in one direction (southeast), the current beneath the ice was moving them in another (southwest) until they finally gave up and changed course.

The sailors who found their bodies thought the three men had simply died of cold and exhaustion. As one put it, “The cold finished them.” This too seems possible.

The final page of Andrée’s water-damaged journal:

………… …… …… bad weather and we fear ……

………… …… we keep in the tent the whole day

………… …… …… so that we could

………… …… …… …… on the hut.

………… …… …… …… to escape

………… …… …… …… …… like

………… …… …… …… out on the sea

………… crash … …… …… grating

………… …… …… …… … driftwood

………… …… …… …… to move about a little

………… …… …… …… ermits

If a bear tries to eat you, shoot him first (bang bang).

Andrée’s journey is peripheral to the research I’ve been doing for my book. I came across the final journal entries in an anthology, and found them haunting. Another book I read mentioned Andrée in passing, the writer intimating that he’d gone forward with the flight only because he was too cowed to bow out, and this impression stayed with me (even though I no longer think it’s accurate). It’s one thing to float toward the North Pole in a hydrogen balloon having other people think it’s a terrible idea; quite another to be floating along thinking it yourself.

In The Ice Balloon, Wilkinson makes a convincing case that it was likely more complicated that that:

I don’t think he left because he was afraid not to. I think he left because he could no longer imagine not leaving.

This seems true. So much of what interests me about the Arctic are the ways it’s like life, but with all the motivations and character flaws exaggerated and set against a blank icy-white backdrop, so all the outlines stand out more sharply. Look at that giant grey balloon lying on its side on the snow and ice — that was once someone’s big beautiful doomed irresistible idea. Why did he go? Because it was his idea, and he had to see how well it could do.

Photos courtesy of Grenna Museum/ Andrée Expedition & Polar Centre. All three photos were taken by Nils Strindberg, a member of the Andrée expedition.

Save Yourself is the Awl’s farewell to 2015.

Apocalypse Tourism

by Rachel Monroe

This year I broke up with someone important and I didn’t know what I was doing for a little while. I spent too much money on a dress with a cactus pattern, but every time I looked at it in my closet I thought: I can’t wear that, I’d look like a tourist. I live in West Texas, and every day I see how the tourists dress up for the desert, all ponchos and wide-brimmed hats, allowing themselves to indulge in fringe.

Several years ago when I lived in an east coast city, my friends and I all talked about moving to a farmhouse upstate, vague fantasies of tomato plants and swimming holes and wood-burning stoves in the winter. Recently, the collective daydream shifted; now everyone wants to come to the desert. In Marfa, where I’ve lived since 2012, a new four-story hotel — the tallest building in town! — is set to open next month to accommodate all the visitors. In October, Travel & Leisure reported on the “new set of creative urban refugees… flocking to the town of Joshua Tree.” For the first time in a decade, more than a million people visited Death Valley last year. Succulents are on trend and there’s prickly pear juice in the cocktails.

The tourists come for the desert’s skyscapes and crumbling adobe buildings, its mysticism and tequila and Instagrammable earth tones. I’m a tourist, too, of course, even if I’m moving at a pace of years instead of days. When people ask me how long I plan on staying in Marfa, I answer vaguely: “It’s not my forever-place.” Whatever that means. Between the fancy grocery store and Amazon Prime, Marfa is hardly a place of deprivation. But even with kale and art openings, the desert is hard. Trash snags in the scrubgrass. Only rich people have lawns. Last week, a pack of stray dogs chased me down the street, and today the wind is so strong it feels like the house is under attack. When I go back east, I always get a little emotional the first time I see a cluster of trees — the easy abundance! All that green!

This is a strange time for a desert exodus. Though the whole world is getting hotter, climate change is affecting deserts much more quickly and direly than other parts of the planet. Cities in the Persian Gulf may be too hot for human habitation by the end of the century; the Joshua Trees will probably all die; there was a historic drought and then historic wildfires; we’re running out of water and draining our rivers; the towns are increasingly meth-y and militarized, and the only one who’s hiring is the Border Patrol.

I used to get so annoyed with people who talked about how end of the world was imminent. The inability to imagine human existence going on after you just seemed like the most grandiose form of narcissism. Increasingly, though, things feel bad in a big way — and I’m wondering whether people are coming to the desert not in spite of, but because of, its approximation of apocalypse. Maybe it’s attempt at inoculation, or a kind of masochism. Or maybe we just want to look at what we’ve done. If the farmhouse is a fantasy of refuge or retreat, the desert is a confrontation. We live among the trash of other eras, their old cars left to rust and their graveyards of historic, pre-pop-top beer cans. It’s too hot, and there is no shade.

I for one celebrate this move away from the bucolic and toward something more harsh and elemental, this aesthetic of bleached bones and regret. It may be too late, but we do the best we can anyway. When there’s no moon, the stars are bright. Our mistakes will outlive us, rusting into something that someone someday might consider beautiful.

Photo by edward musiak

Save Yourself, a collection of essays from writers we love, is the Awl’s goodbye to 2015.

2015, In Order

12. February

11. January

10. March

9. December

8. November

7. April

6. August

5. October

4. July

3. May

2. September

1. June

Related: 2014, In Order

Photo © 2010 J. Ronald Lee

New York City, December 17, 2015

★★ The top of the ostentatiously tall building for billionaires was being clipped by either high fog or a low clod, depending on how one felt about ambition. The walk to preschool was dry, over sidewalks still damp at the joints and edges. Wet blurry halos spread around the leaves on the concrete. The grass in the Park, seen though the open taxi window, was deep green. Rain started and gradually intensified. The hood of the waterproof jacket settled low and protective, doing its job. The Italian place late at lunchtime was warm and full, all clatter and electric light, so even the wait for a takeout sandwich felt civilized. The rain fell harder. The new seat in the office looked right out over Fifth, and the drops were splashing the puddles there forcefully enough to be seen three stories up.

Why Be a Renter When You Could Be a Sharelord?

Given mounting to opposition to Airbnb from various, disparate parties, one might reasonably ask how the company will fulfill its grander ambitions of making it so that “every person in every country can stay with someone on Airbnb,” and in the process, push forward a “broader evolution in capitalism,” in which one’s property and time become assets from which value can be unlocked by app middlemen, allowing you to maintain your ever-tenuous class position.

While the Home Share Lobby works on transforming government policy so that it is more favorable to Airbnb, the company is taking a more straightforward route with an opposition group motivated more directly by self-interest: landlords, who currently don’t get a cut of the revenue their tenants receive for renting out the apartments that they own. According to Bloomberg, Airbnb is “reaching out to some of the largest U.S. apartment owners with the aim of working out a deal in which tenants can rent out their units through the website — and have their landlord’s blessing.”

Any agreement would probably include some kind of revenue sharing, giving landlords a cut of income the tenants earn from renting out their apartments, said Rick Haughey, vice president of industry technology initiatives at the National Multifamily Housing Council. Negotiations would need to reassure owners that they’d have a say over what happens at their properties.

… Partnerships between Airbnb and landlords initially would be limited to markets where the legality of short-term rentals isn’t in question, the person with knowledge of the discussions said. That would rule out New York City for now but possibly include cities that have passed home-sharing regulations, such as Philadelphia; Nashville, Tennessee; and San Jose, California, according to the person.

This is only logical: If we arrive at the point where everyone is Airbnbing their apartment — or least thinking about it — the only possible result is that landlords begin baking that assumed income into the rent as a more complete assessment of their apartments’ value. If Airbnb signs deals with landlords, it would formalize such an arrangement and remove the lingering ambiguity that many hosts face about the legitimacy of their enterprise — and, in some cases, the risk that they might lose the very home they’re trying to keep.

But going a little further, one might ask: What does a slightly more efficient Airbnb look like? Who or what, given sufficient time or policy or technology, is less necessary than other components? For Uber, which efficiently allocates things in need of transit into empty car seats, drivers are openly a stopgap until driverless cars are ready sometime in the next fifteen years. Airbnb, viewed abstractly, efficiently distributes travelers into empty, extant rooms or homes, extracting value from underutilized space. Strictly speaking, the permanent tenants of those homes are not necessary, only the space. In the case of apartments it would seem more efficient for Airbnb to deal directly with a property owner than to sublet the space from a tenant. But removing tenants from the chain, however efficient, contradicts with not just the entire thrust of Airbnb’s current PR campaign for home-sharing — that it provides an economic lifeline to the middle and working class — but the policy goals that it is working toward, which would enshrine the right to share the home in which you live, whether you own or merely rent it.

Priorities shift though. Right now, at least rhetorically, much of Uber’s advocacy is around jobs and drivers, who leverage their time and vehicles to transport its users. (Uber even provides loans so that people can buy cars to become Uber drives!) But it’s clear, even today, that it will abandon them as soon as it is able to. In fact, it’s hard to overstate just how radically driverless cars will transform Uber: Currently, not a little of its value is predicated on how much of its infrastructure it doesn’t directly employ or own — meaning that it is very efficient — but a driverless world seems to all but require that Uber own or directly control its entire fleet.

Airbnb is slightly more opaque about its future, but there are probably hints in CEO Brian Chesky’s recent obsession with the hospitality industry, detailed in a Fast Company profile last year that also discussed the company’s hire of boutique hotelier Chip Conley:

“Our business isn’t [renting] the house,” Chesky says. “Our business is the entire trip.” His idea is to create a portfolio of new services that make the Airbnb experience more consistent from stay to stay, and that can generate lots and lots of additional revenue. One starting point: a cleaning service that will offer fresh sheets and towels to Airbnb proprietors. … Chesky’s first directive to Conley was to create a set of hospitality standards that could make the Airbnb guest experience more reliable. The aim was to figure out which baseline comforts Airbnb ought to offer guests, while embracing the unique, local, and often unpredictable charms its hosts provide on their own. In November, Conley rolled out nine such standards for hosts to follow. Some, like pledging that a listing is accurate, are general to the point of blather. But others specifically address cleanliness and appropriate ways to interact with guests.

Standardized hospitality and consistency, which would make Airbnb more hotel-like, seems to preclude the individuation of millions of regular, middle-class people sharing their homes, and points toward the ideal host being something between a landlord and a hotelier — or even toward Airbnb more directly controlling properties, even if much of its current value, like Uber, is tied up in the idea that it doesn’t actually own property. Then again, part of the pitch behind WeWork — the terrifically conventional real-estate company disguised as a startup which leases property, adds amenities like beer kegs, then sublets it to tech workers at a premium — has been that it is “asset-light,” meaning it owns no property, and yet it is now in the process of developing one. Which is all just a way saying it wouldn’t be so surprising if, in the next couple of years, Airbnb opens something like a “model hotel,” not unlike Amazon’s physical bookstore.

More broadly though, there’s a lot of property out there that could be developed into a fluid-use space, and whose value could be more thoroughly extracted if its usage and occupancy were allocated and distributed through a platform. Right now, cities largely make those decisions through permits and other regulatory frameworks; a loosening of that regime would, at least in the short or even medium term, make those properties more valuable by allowing platforms to take over that role. This is exactly what Airbnb is arguing about private homes after all: That cities — or even landlords — should not have the right to prevent the people who live there from doing whatever they want with it, like subletting it whenever they’re out of town for a weekend. Now extend that argument to every building in every desirable location, their utilization maximized through a platform: Wow, they all seem so much more valuable now.

Who knows though? It’s hard to predict what happens if we throw, like, traditional notions of the government enforcing property rights out the window and grant that to a large, ascendant middleman, because that’s precisely when things get weird. But one suspects there’s probably never been a better time to own a little piece of property in the heart of a very cool city.

New York City, December 16, 2015

★★★ No clouds were in the morning sky, but the sun still had trouble finding an angle down to the streets. People were bundled up again, but not fearfully so. At last the light got high enough to hit the corners of a column of balconies, and to illuminate the fine, fully bare branches where the last bright red leaves had been. By the end of the early afternoon school choral concert, the sun was gone, the sky covered in clouds that looked as absolute as the blue had. From up in the apartment, there was an opening in the cover still, down in the southwest. The light came rippling through it and spread highlights or lowlights along the bottoms of the clouds in a premature version of sunset, with dun and gray doing their best imitation of what scarlet and purple might do. Straight overhead the sky was abruptly clear blue again, then just as abruptly there was a pebbly field of cirrus there, then smoother cirrus. Down toward the sun all kinds of bright shapes were getting tangled up. By the time sundown really arrived, things had settled tastefully and anticlimactically on soft blurry pinks and bands of white. The night streets, on the way out to the grocery store, were shiny. It was raining harder than it looked like it was.