Beautiful

by Paul Ford

I used to tutor this guy, I’ll call him James. I was about twenty, and this was twenty years ago. He was a guy about ten years older than me at the time. He was getting a graduate degree in counseling and was dyslexic. I was just about to graduate with an English degree.

James would come to my apartment and we’d work on his papers. I was paid minimum wage to work with him. It was pretty good work, because I liked him and I’ve always liked helping people write, and I also got to see what people learn in graduate psychology classes.

We were in a tiny town in upstate New York. The town was totally white, and the campus was extremely white, and James was black, and about six-foot-three, so he really stuck out. I remember when OJ Simpson was found not guilty, James saw me and he said, “Paul, white people are heated! Heated!”

I said, “Well, I mean, OJ probably did it.”

James said, “But Paul, I didn’t do it!”

One day we were typing up some notes from a visit he did to a prison. The notes were pretty fascinating. James would interview the prisoners about their problems. I asked David, who is serving a five-year sentence, what he liked to do to relax and he said that it was ‘smoking crack and having sexual intercourse,’ and then I asked David how he felt he could improve his life after prison and he said, ‘I need to stop smoking crack before sexual intercourse.’

James had rough handwriting, and would replay conversations from memory later. He had a great memory, for obvious reasons.

I was finishing up my English degree and writing a thesis on the hegemonic literary canon; James was talking to prisoners about smoking crack and getting his MS in counseling so he could be a social worker. We would type up his notes at my place — I’d use WordPerfect on an old DOS machine that someone had given me. Then we’d go out and drink.

One day James got bored with our work and went to the mirror in my apartment and began to pat his hair down and nod.

“Look at that ugly son of a bitch,” I said. Which was a normal thing for me to say to him, or vice versa. We were both giant dudes and we made fun of each other all the time.

And he got a tiny bit serious-looking right then, and didn’t turn his head, just kept looking in the mirror, and said, firmly, “That’s a beautiful motherfucker.”

“Right,” I said.

“But look at this,” he said. “Just look at this beautiful motherfucker. Paul, that is an absolutely beautiful motherfucker right there.” He made a “hmm” noise, like he’d just eaten something wonderful, as if his beauty were delicious.

He kept saying it, three or four more times, beautiful, beautiful, beautiful, beautiful. As if I weren’t in the room. Until finally I said —

“Yeah, yeah, I got it. You’re a beautiful motherfucker. Let’s get back to work.”

“That’s right,” he said, and we got back to work.

I think about that conversation. I’ve been thinking about it these last few weeks, and for the last twenty years. Sometimes things feel very out of control. I have too much to do, I have children, I have a whole life that keeps sliding out from under me as I try to stay on top of it. You are allowed to do this, though: You can go to the mirror and say, “Just look at that beautiful motherfucker.” People can be telling you the opposite, in a million different ways, you can be telling yourself that you are the opposite of a beautiful motherfucker, but they can’t actually stop you from standing there and putting your hand on your head, repeating those words or words like them. Until the other party gives up and just lets you say it, and then you can get back to work. Also remembering that the only reason James protested his beauty on that day was that I had told him that he was one ugly son of a bitch.

Photo by Les Chatfield

Save Yourself is the Awl’s farewell to 2015.

Not Lived Up To

In San Francisco’s Northpoint Theater at 10 a.m. on Sunday, May 1, 1977, San Francisco Examiner feature writer John Stark attended the premiere of a science-fiction movie at the invitation of a friend who worked as a theater booker. “No press allowed,” this friend had told him. “It’s a single screening by Fox… to gauge audience reaction. If you want to go I can sneak you in with the projectionists.” Stark was in his early twenties at that time, up for whatever: “There was no buzz about the film,” he wrote in a blog post, many years later. “How could there be? No one had seen it… The sci-fi genre was considered deader than dead.” The pair seated themselves just before the show began. “The auditorium was packed with people of all ages,” Stark recalls. “There were a lot of families.”

“That’s the director, George Lucas, sitting in front of us,” his friend whispered.

Lucas, in attendance with his wife, Marcia, was anticipating the worst, according to a highly entertaining account of the morning’s events in Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, Peter Biskind’s seminal book about seventies Hollywood. “Previews always mean recutting,” the director surmised gloomily.

“The suits were there, Ladd and his executives,” Biskind wrote. “Marcia had always said, ‘If the audience doesn’t cheer when Han Solo comes in at the last second in the Millennium Falcon to help Luke when he’s being chased by Darth Vader, the picture doesn’t work.’”

Stark described what happened next:

“A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away.”

I was taken aback. The past? Whoever heard of a sci-fi film that didn’t take place in the future? But that was only the first of the film’s many startling innovations…

As the plot unfolded the audience became more and more pumped: cheering, laughing, clapping. It was as if we were all passengers on a fantastic journey. I’ve yet to experience a more electric moment at the movies than when Han Solo’s spaceship, the Millennium Falcon, jumped to lightspeed. The man sitting next to me had his little girl on his lap. They both screamed with joy. The whole theater did.

I was a teenager at that time, and found myself just as transported as the rest of the world, easily shedding my proud, foolish carapace of habitual ennui. It was the wrong sort of movie for an uppity teen to like, not having been directed by Jean-Luc Godard or equivalent, but everything about Star Wars was that irresistibly fresh and new, and we uppity teenagers fell for it in droves. It’s wonderful to me, too, that Marcia Lucas should have known exactly what the key moment in the film was, having labored and thought over it for years with her husband, without having the foggiest clue what effect that moment would have on a real audience. Its appeal, its message of redemption and loyalty, the surprise of it — so perfectly timed, so obvious-but-not-obvious — is a nakedly emotional one. Sure, people have to look after their own interests. But when they come forward, despite everything, to risk themselves on something they believe in, something greater than themselves, in honor of friendship, or of justice, or out of some other private imperative? It’s the most thrilling thing in the world.

There’s a lovely old phrase my mom taught me: “mi novio del cine,” “my movie boyfriend.” That is, the movie star of one’s dreams. Harrison Ford has always been my chief novio del cine.The Empire Strikes Back, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and Blade Runner debuted in 1980, 1981 and 1982 respectively, and it was as if Rick Blaine had come back to life. Or rather, some alchemically potent combination of Rick Blaine, George Bailey, James Bond, and Allan Quatermain. Harrison Ford, detached, comely, witty, playful, elegant, though not too elegant to appear in a mass-market entertainment, was like a cisphoon, a cisnado or cisquake (The Big One) of male beauty. He was altogether disturbing to a teen, and in the best way. That old phrase! Sex Appeal.

My younger friends have been mystified, even outraged, that I do not care too much for the new movie. It’s been difficult to explain my disappointment exactly, when there is so much about it to admire. The Force Awakens is a thousand times more impressive technically than the first and second films, Episodes IV and V; it has the most wonderfully appealing new characters in Kylo Ren, Rey, Finn and Poe Dameron; it has excitement and dash. [Ed. note: Spoilers follow*, you baby.]

What it does not do is evoke a single strong emotion, so much as the ghost of one — even in the face of genocide, the destruction of whole planets. Not that I absolutely require fiction to produce some specific sign of the cross on our behalf in depicting a tragedy; not when at this very moment there are tens of thousands starving to death in the real world, just for starters, and the real news goes by every day without so much as a mention of them. Seen in a certain light, it would be a disgrace to demand empathy in the movie, considering what is really going on out there. This is escapism and fun, and lord knows we could use that.

But even so, the film failed to create what I most wished to feel: real grief at the passing of a cultural moment. By rights I should have felt, very much wanted to feel, not sad but inconsolable, given what Han Solo has meant, not just to me but kind of at large, during the greater part of my life. But the moment just raced by — oh, sad! and whoosh to the next thing — it was derivative, unexplained and unfelt. So that the concept of adulthood of a whole generation, forged in no small part according to the imagination and wit of Harrison Ford, was forgotten or misplaced in the mad rush to satisfy — what? The visual impulse, maybe: achievement unlocked there, for sure. Maybe also there was an understandable desire to bury the failed prequels in a series of deafening echoes of the original trilogy, the part of the story people are loyal to. I appreciate that a lot, because we really are very loyal. I mean, for literal decades my main to-do list has been headlined There Is No Try.

Part of regret is feeling the loss of those beautiful things that have been degraded or lessened, or otherwise not lived up to, but there is a lot more to it.

Oriel College, Oxford, is trying to figure out what to do about its giant statue of Cecil Rhodes after students at the University of Cape Town decided they had had enough of their own Rhodes statue, which was removed from its pride of place on the UCT campus last April after a student named Chumani Maxwele flung a bucket of poop over poor closeted old Cecil, thereby igniting a series of protests that became known in the press as “Rhodes Rage.”

The dude who threw shit at the statue of Cecil Rhodes is my inspiration, because what else is there to do with that kind of thing?

— Aaron Bady (@zunguzungu) May 15, 2015

There have been a lot of attempts at revisionism this year, one way and another. The Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam is changing the titles and descriptions of various exhibits with a view to eradicating racist words such as “negro,” “Moor,” “Mohammedan” and so on, changing, for example, the title of a painting from “Young negro girl” to “Young girl holding a fan.” Woodrow Wilson’s racist and segregationist beliefs were characterized as a “toxic legacy” by the New York Times Editorial Board last month, as student protesters demanded the renaming of Princeton’s School of Public and International Affairs.

The answer won’t and shouldn’t be the same in each instance, but the dangers inherent in this sort of erasure should be considered very carefully. In particular the desire, often seen among the young, not to be offended, to somehow get rid of every offensive thing or utterance, is terrifically dangerous.

No: Be offended, speak up, don’t try to shut anyone down, make them reveal themselves! If you shut people up, hide the statue, their bad feeling won’t go away, history won’t go away. It will only fester in some gross corner. We can only bring the new world about by getting in a big family argument of the sort we all dread but somehow survive every year. Granted, that can be uncomfortable. But it is extremely useful. For example, the sole service ol’ Biff Trump has done the nation is to show, day by day and in painstaking detail, exactly what it is that must be stopped dead in its tracks come November.

Cecil Rhodes, zillionaire founder of the DeBeers diamond empire, was a fucking monster. He is a real embarrassment to anybody who would defend the patriarchy. Here he is in 1887, addressing the government on whether or not to permit “the natives” of South Africa the vote:

Does this House think it right that men in a state of pure barbarism should have the franchise and vote? The natives do not want it […] let them be a subject race, and keep the liquor from them […] We have to face the question and it must be brought home to them that in the future nine-tenths of them will have to spend their lives in daily labour, in physical work, in manual labour.

Today, black Rhodes Scholars from Africa attend Oxford. William Jefferson Clinton, also something of a monster — though substantially less of a monster than Cecil Rhodes — was a Rhodes Scholar. There are just a handful of tenured professors at the University of Cape Town who are black. Wilson was a segregationist horrorshow, and also he was the president of this country, if a weak one; a founder of the League of Nations, and a pacifist. What I mean by all this is that every institution we possess is irremediably tainted.

We don’t want to get rid of the past; what we want is to regret it. Move the statue, yes, but don’t destroy it. We must supply ourselves with plenty of buckets of poo, and never forget a thing. Oxford classicist Mary Beard made a similar point a few days go in the Independent, expressing admiration for student activism and resistance to racism, but cautioning against what she saw as a “dangerous attempt to try to erase the past.”

“Of course Rhodes was a racist,” she said. “My worries are about the narrower historical point: that history can’t be unwritten or hidden away, or erased when we change our minds. We need to face the past and our dependence on it and do better than it… that’s what the past is for.”

In other words, if we get rid of the statue, where will we even aim the poo.

To regret is three things: to lament our personal failings; to mourn the lovely things that are irretrievably past; and to know our own brevity, the fleetingness of the bad, as well as the good. It is among the sweetest and most perfectly human of emotions, and it is to be sought, and savored. Without regret we will understand nothing about where we are, or how we arrived here; what we did right, or wrong. Quoting Seneca in an essay, Francis Bacon wrote in 1625: “The good things which belong to prosperity are to be wished, but the good things that belong to adversity are to be admired.” It hurts, but that’s all to the good; through your whole life, everything you feel is going to have been worth it. We need to look back, in love and in sadness, in order to know ourselves.

*Honestly, if you care that much about being spoiled, why haven’t you see the movie already? But I also don’t feel like dealing with mad Twitter eggs, so who is really the baby here?

Save Yourself is the Awl’s farewell to 2015.

The Troll Awakens

by Katie Notopoulos

Early in the day that the new Star Wars movie came out, my boss and I were joking about how it would be really funny to do fake spoilers. I remembered a really funny time when Adrian Chen tweeted out a fake spoiler for The Dark Knight Rises in the Comic Con hashtag when the trailer first came out. The genius was that he made the fake spoiler as an image, the tweeted out, “Whoa, very hot Suicide Girls at #comiccon #SDCC”, thereby tricking horny Comic Con attendees — the ideal marks — into seeing it. So I attempted a blatant ripoff of Adrian. I put the fake spoiler into the bottom of an image, and tweeted with it “Holy shit — Martin Shkreli releases the Wu Tang album!” (Martin Shkreli was very topical that morning). A bunch of people replied something like “fuck you,” and I cackled, feeling smug under my assumption I’d be vindicated once it was clear that this was a fake spoiler. Just another zinger from ol’ trollmaster Kapie. Kek kek kek. The problem was, it turned out my “fake” spoiler actually happens in the movie. It was a real spoiler. Oops. I respect spoilers. I love movies! I love the wonderment and emotion and attachment we have to the noble and beautiful art of the cinema. I respect people’s right to enjoy Star Wars without knowing a key plot point in advance. I felt absolutely fucking awful. Since real spoilers for the movie were actually out there on the internet that morning, people thought that I had found a real spoiler and did it on purpose. That night I got a Google Alert for my name for an article about spoilers that said, “There will always be malicious folks who blast out spoilers simply to troll — like Buzzfeed’s Katie Notopoulos, who tweeted out an image of probably The Force Awakens’ biggest spoiler on Thursday morning for no reason other than to screw with people…” That’s not me! Sure, I was trolling but not maliciously! I’m the nice troll not the bad troll! I didn’t mean to hurt anyone. I regret this very much.

By the way, it WAS really weird how there was that really long scene with C-3PO’s nude dick.

Save Yourself is the Awl’s farewell to 2015.

Trying

by Emma Carmichael

In the final few weeks of what was, for me, a pretty bad year, a phrase has hung around in my head. I say it to myself sometimes: “Babe. Neither of us r the same.” It’s a seven-word excerpt from a Twitter story that captivated the internet for a few days this fall, and it’s only as deep as you want it to be.

About six-and-a-half months ago, my cousin and I were crushed between the passenger side of a fourteen-thousand-pound Ford F450 truck and a line of cement Jersey barriers, the only objects that separated us from a very long drop into very shallow water. It was a Thursday in the first week of June, nearing midnight, and we were trying to get from New York to Rhode Island for a bachelorette party. We had a flat tire, and then the car caught fire and, anyway, we made it as far as the Q Bridge in New Haven.

I’ve been having a hard time writing about what happened, which is odd because I find it easy to talk about. I talked about it my first conscious day at the hospital, when I was so loaded with narcotics that I don’t remember a single word I said and regularly picked up imagined fragments of conversations out of the air. “Did you talk to the guy?” I’d ask my dad, out of the blue. I’m told I said a lot. I knew some details, the basic angles, of what had happened. I remembered the way a pair of headlights flashed in a stranger’s eyes right before my back, pelvis, and leg were shattered and my cousin, Molly, nearly bled out onto the pavement a few feet away from me.

Neither of us are the same. I’m still learning how that will be true. A week into my hospital stay, a doctor mentioned that I’d broken my back, a detail no one had yet told me. A few months ago at a follow-up appointment, my surgeon said that they’d been unsure whether or not I’d keep my leg. I look at my leg and try to imagine it gone; I look at the new titanium in my X-rays and try to imagine the surgery, my skin opened up to bright lights and probing tools. It’s hard to excavate or linearize the in-between, the moment the loud noise in my memory became the scar on my leg, the way I flinch at certain sounds now.

I talked about it in the weeks following, as friends came to visit. “Want to hear what I remember?” I’d ask. I was prepared, even if my audience was not. For a while, I found comfort in re-telling it, and even in seeing their horror. I couldn’t remember much, but I could tell you about where we’d been standing, and just how it looked when my vision mercifully faded black as I went into shock. Telling it, more than the rods protruding from my body — four down my left leg, one in each hip — was proof that it had happened. It all felt like a dream, so the story mattered.

At dinner not too long ago, I found myself using salt and pepper shakers to show where the cars had been, a fork to show the side of the bridge. See? And then, after a long look: Is this weird? Another time, meeting with a new physical therapist, I found I had to stifle laughter mid-story as her face shifted from interested to frightened. It’s not that it was funny, it’s just that I didn’t know what I could say to comfort her — and yet I knew that part was up to me, too.

Like any good, accommodating young woman, I have learned how to read my audience, to decide how much of myself I’d like to give someone or how much they can take. I have, by my own measure, overshared; I have also said very little. Once, when I was on crutches at a house party, someone asked what had happened. “I broke my leg,” I said. A friend guffawed. It was true, I pointed out later.

A story becomes less your own when a public version of it exists, which is a funny thing for a blog editor to learn first-hand. One day removed we were already “pedestrians” who’d “suffered serious injuries to their lower extremities”; not long after that I was the editor of a “a popular news site” who was “recovering from a fiery 3-car crash.” We learned, quickly, that much of figuring out what to say meant deciding what kind of reaction we were game for. Molly won’t say “car accident” because she thinks it diminishes the fault of the driver that hit us. Sometimes I say it anyway because there are fewer follow-up questions. “I got hit by a truck” is technically true but also gets a double-take. “Car fire” is incomplete; “flat tire” feels like an inside joke. “Well, babe,” I think I’d love to tell a stranger, “neither of us are the same.” I’m still figuring out how to control the story’s general emotional power; sometimes even just stating the facts induces tears.

I’m surprised at the way the arms of my trauma unfold and pull people in. The young man who stopped to help us says he no longer slows for cars on the side of the road. My dad remembers the caller ID flashing late at night, an institutional voice on the line asking if I was his daughter. My younger brother thought, for thirty minutes between phone calls, that Molly and I were both dead.

“I went over to the first victim,” one of the first responders on the scene told a local news station the next day, in a segment I watched twice and then never again, “and I thought she was just leaning up against the truck. She told me that she was trapped and that her cousin was trapped. I didn’t see her cousin so I looked over and it was one of those, oh my god moments.” I don’t remember seeing him, but I try to place myself there, stuck, hurt enough to scare someone.

When I left the hospital in July, after a six-week stay, I was in a wheelchair and had a series of metal bars protruding from my pelvis that made it look as if I had a perpetual, giant boner; some weeks after that I was using a walker with tennis balls on its legs to get around New York City; a few weeks after that I was on crutches. I only just ditched the crutches at the beginning of December. For the first time in more than six months, I have no signifier that announces that Something Bad Happened Here, so I don’t have to explain myself as much. This is both a startling adjustment — what am I now that I’m not hurt? — and a welcome one. It’s nice to get around unaided, and to skip that conversation, the probing addendums that come with it: Many people have absurd unsolicited advice for how we should have behaved differently when we nearly got crushed to death.

You shouldn’t have pulled over, I’ve heard. You should have run, I’ve been told.

But we were so lucky, I’ve said again and again. I know it’s true, and also that it’s a hollow line for a moment of chance I’m unable to make sense of. I try to understand it as a physics problem — salt and pepper shakers and a fork — but I was never any good at physics. My cousin and I both turned to our left at this moment, and then we turned back to our right at this moment, and for some reason, when the truck crushed us, it did not paralyze or kill us. God sent His angels down to that bridge to save you, a nurse told me as I cried in her arms in the hospital one morning. I nodded because I needed to feel the warmth of her belief as much as she needed to have something to say. Some people have told me we should have stayed in a burning car, and I don’t have much to say back. If I can’t fill the in-between, at least I can listen to the version of the story someone else is more comfortable hearing. The physics of it, though, are no more comprehensible to me than a nurse’s conviction that I was saved by God. I don’t understand why it wasn’t final. I try to understand that what I am dealing with here is essentially the results of unfortunate circumstances and fortunate spacing. I try to picture it.

I’ve been made to believe that a natural progression from a close encounter with death is to have a new perspective on things, maybe a steelier resolve. On some level, this must be what people mean when they ask me now how I’m doing, or if things are back to “normal” yet. Molly and I talk about how our version of “normal” has necessarily shifted, but that’s a functional blanket for an infinite number of things that have slowly moved around, not a sudden tectonic rupture. It’s not that deep, but neither of us are the same.

When I was staying in an accessible building this summer, I often sat out on the balcony in my wheelchair, five stories up, and calmly pictured the structure departing from the building facade and dropping me into traffic in the West Village. Not long ago a curious but erratic cab driver brought me through a quiet section of Bushwick, asking me about my crutches. As we crossed a four-way intersection I saw an eighteen-wheeler coming at us with no signs of slowing. The driver accelerated slightly and I looked out my window at the approaching headlights and thought to myself, “Oh, it’s going to happen again.” The how of it speeds by, and all I can see is the collapse.

A few months ago, I found some comfort in the part of the narrative I knew. Now I’m trying to find comfort in what I don’t, that proximity to powerlessness, in not really knowing what to say.

Photo by Emma Carmichael

Save Yourself is the Awl’s farewell to 2015.

New York City to Elizabeth, New Jersey, to New York City, December 27, 2015

★ Fog whitened the view out the window like a coating of road salt. The bleak lights in the Port Authority bus garage were consonant with the wan daylight coming in where it opened onto the ramp. Fog chopped off the boom of a crane atop a rising piece of the new West Side. The bus looped up out of the tunnel, and off to the right spread a glowering midrise version of Manhattan. The plants on the rock embankments were still green. Out in the marshes, the waters were as matte as the paint on a boiler-room wall. Where no one had bothered to build a stretch of sidewalk between the mall and the hotel complex, the bare dirt of the desire path was dark enough to steer around. The lights of the football stadium shone clearly in the distance across the flat brown landscape coming back. The city looked still fogbound from the bus, but after it finished creeping its way through the tunnel, and after a quick subway ride, the air near at hand seemed clear in the blueing dusk, and a gust came down Broadway.

The Year I Was About It

by Jenna Wortham

This morning, I got an email quoting from the foreword from Near to the Wild Heart, the sensational first novel written by Clarice Lispector, an elusive Jewish-Brazilian author who published the book at twenty-three and then all but disappeared, sending the Brazilian literary world into a frenzy. Near to the Wild Heart is a deep-water submarine, exploring cavernous interior lives, and the raw and unfiltered power that comes from reflecting on how we perceive life and how we live.

In the foreward, her biographer, Benjamin Moser, writes that Lispector had a fundamentally different conception of art. It was less of an intellectual, or even artistic pursuit. It was spiritual. “The possibility of uniting a thing and its symbol, of reconnecting language to reality, and vice versa, is not an intellectual or artistic endeavor,” he writes. “It is instead intimately connected to the sacred realms of sexuality and creation. A word does not describe a pre-existing thing but actually is that thing, or a word that creates the thing it describes: the search for that mystic word, the ‘word that has its own light,’ is the search of a lifetime.”

As 2014 wound down, I took stock of myself, took note of the relationships and imbalances that were making me unhappy, and then started to strategize about how to color-correct them. I stopped whining about what I wanted my life to be like, and started to investigate why I wanted what I did, and then began the process of figuring out how to make my life mirror those desires. 2015 was the year I forced myself into an entirely different conception of life.

Put another way — like Trina does on her guest verse on Pitbull’s “Go Girl”: “Don’t talk about it boy / Be about it boy” — 2015 was the year that I created space to figure out what “it” meant for me, and then started to understand what it meant to be about “it.” All of this is a very long way of saying that I didn’t have many regrets this year. To get closer to your true self means spending a lot of time interrogating your current self, looking at the parts you don’t like under extremely sterile lighting, acknowledging them, then making peace with them. It was not pleasant, and although I didn’t find the process of self-excavation tremendously unpleasant, it wasn’t painless, or easy. Not to get all Chani Nichols about it, but altering how I move through the world means living with my eyes facing forward, honoring the past, but leaving it behind.

That said, there is a very short list of things I do regret about this year, and they are listed below, in no particular order:

1. Minutes (hours?) spent in the particular kind of speechless white-hot rage that only the Internet can induce

2. Learning about the dab too late to do anything clever with it :/

3. My continued hyperdependency on Amazon Prime, Seamless and Uber

4. Sleeping on the Rihanna Anti-World tour pre-sale

5. Not dating women sooner. Like whoa.

Giph from “A Message”

Save Yourself is the Awl’s farewell to 2015.

Money from the Sky

by Chris Arnade

An amorphous group of well-connected bankers and economists — and the politicians they support — run global economic policy. On Wall Street, its members are called Smart Money, and they usually come in the form of a hedge fund manager who lives Manhattan or London. They wear clothes bought in SoHo in NYC, or Chelsea in London (Never SoHo in London or Chelsea in Manhattan), and they have slicked back hair, snazzy glasses, Ivy League credentials, and global think-tank connections.

Their view on the seventies is rather dim. Bankers never like inflation, since it withers away the value of the money they lend, and the seventies was further proof how destructive it could be; New York and London were in disarray, rife with crime and run by governments spending too much on silly things like welfare. It was before the dual-headed deity of banking, Margaret Reagan, rose from the ashes to set things right and deliver an edict: Kill inflation and government spending (well, not the defense part). For the last forty years that paradigm has ruled, and Smart Money has supported economic policies steeped in moralistic platitudes about sound money and mathematical proofs about the value of austerity. The result was a financial boom that was good for the markets and very good for their wealth.

Now, inflation is dead and growth is close to nonexistent; Japan hasn’t had much of either for over twenty years, the U.S. and Europe for close to ten. It has left Smart Money stuck, desperately trying to get the world growing again. Since they don’t like government spending, that means finding a way to get people to spend, or markets to climb. In the past, that meant interest rates cuts, which made it easier to borrow to buy homes and cars. But rates are at essentially zero and — despite having sent markets higher — nobody is spending. In Europe rates have even gone below zero, making borrowing costs negative: You have to pay to put your money in a bank account. Gone are the days of getting a free toaster or iPod when you open an account. Now, you have to give the bank a toaster or an iPod.

The U.S. is in slightly better shape. After nearly six years of zero interest rates, the Federal Reserve raised rates earlier this month to just a quarter of a percent above zero. It could easily be a short-term thing. Inflation is still very low, and growth is low, fragile, and at risk of a shock — like a terrorist attack, or another recession (which usually comes every three years or so.) If that should happen, the Smart Money in the U.S. will suggest we follow Europe’s lead and cut rates to negative, pushing markets — and their wealth — higher, but hurting most everyone else.

Or maybe, hopefully, they will support something less disruptive, more effective, and more egalitarian: Just print money — literally print it, not borrow it — and give it to everyone. It is an idea that some economists have suggested for a long time, including one named Ben Bernanke.

When I joined Wall Street as a bond trader at Salomon Brothers in 1993, the Smart Money’s ranks were swelling, riding a wave of deregulation and globalization. Gone were the smaller and quieter private partnerships that had dominated investment banking since the thirties, replaced by sprawling global public companies selling complex financial products. Margaret Reagan was also gone, but there was a new dual-headed acolyte in Bill Blair.

My first boss was classic Smart Money, a well dressed managing director who worked tirelessly, had a genius for making money, and was always concerned that his wealth was about to disappear. “Do you see what is happening in Brazil? A thousand percent inflation and the government seizing bank accounts.” Our office was in the World Trade Center, and whenever we went to a business meeting in midtown, he would wave down a black cab. If I suggested the subway was quicker, he would scoff, “Too dangerous, it is filled with tuberculosis.”

The Smart Money world view dominated, but cracks were starting to appear. Japan was on the backside of a mother of all financial bubbles, which had imploded spectacularly in 1991, and it was stuck in a depression it was unable to escape. Japan cut rates, as prescribed, but growth wasn’t coming. With its rates at zero, they started spending more and more, hoping to get anything going. The Smart Money smelled blood, sensing an opportunity to exploit what it saw as a massive mistake, convinced that the spending would lead to inflation, or worse, a complete implosion of the economy from too much debt. After repeated trips to Tokyo, countless dinners with their cohorts in universities, think tanks, and governments, Smart Money re-focused its trading books to bet that Japan would implode in a future crisis they had already labeled the “Sakiiiii bomb.”

It didn’t happen. The bet became known as the “widowmaker,” leaving the Smart Money with a lot of losses, and bad memories. It also was responsible for one of my favorite trading floor exchanges:

Trader 1: “What is the smart money doing in Japan?”

Trader 2: “I don’t know what the smart money is doing, but the dumb money is running them over.”

For the next twenty years, Japan spent its way to debt three times bigger than it was in the nineties. It never experienced mega-inflation; it didn’t grow much either.

Around that time, the chair of the Princeton Economic Department, Ben Bernanke, who had studied and written extensively about the Great Depression, was also thinking about Japan, which was following the conventional path of having its central bank cut interest rates to get people to spend. The problem, he thought, wasn’t too much inflation and too much government spending, but the opposite: too little inflation and too little spending. In a December, 1999, he gave a talk outlining how Japan should deal with its low growth and low inflation:

An alternative strategy, which does not rely at all on trade diversion, is money-financed transfers to domestic households — the real-life equivalent of that hoary thought experiment, the “helicopter drop” of newly printed money. ….. Then the real wealth of the population would grow without bound, as they are flooded with gifts of money from the government. Surely at some point the public would attempt to convert its increased real wealth into goods and services, spending.

This idea was both simple and old: Japan was not growing because people were not spending, no matter how low interest rates were, so the central bank should just print money, without borrowing it, and give it to everyone (the “helicopter drop”). Then keep printing money and keep giving it to people until they started spending, and the economy — and inflation — should start to grow again. This idea had been proposed long ago, by nerdy economists doodling around with the very problem Japan faced, something they called a “Liquidity Trap.” It was an idea that didn’t just break the Smart Money edicts, but did so spectacularly. It was uber spending, an indiscriminate dispersion of wealth that gave money to everyone (even the poor!), didn’t increase debt, and was sure to cause inflation. The Smart Money laughed at Bernanke, and whenever he appeared on business shows, his face on the TVs of the trading floors, whoops of “Helicopter Ben!” would rise above his words.

“Helicopter Ben” was serious though, and besides being a great economist he was a good politician, so he downplayed his edict-breaking musings and kept climbing the policy ladder. After a period as a member of the U.S. Federal Reserve, in 2006, “Helicopter Ben” became its chairman.

Two years later, an economic crisis consumed the U.S. as the financial system that the Smart Money had constructed came undone; markets collapsed, and many banks went underwater. The policy that Bernanke unleashed to deal with it was two-pronged: The Fed, which Bernanke ran, printed money, while the U.S. government bailed out the banks and the financial system, under TARP. The government, now partly controlled by Obama, also gave out borrowed money to the “plebes” via the “American Recovery and Investment Act of 09,” pushing up the government debt, and angering the Smart Money. Meanwhile, Bernanke’s Federal Reserve, unable to cut rates any lower, did begin to print money under a complex program called Quantitative Easing. The money wasn’t given out, but used to buy a lot of government bonds, in an attempt to bring the longer term cost of borrowing down and to encourage spending (print money, spend it on bonds, cash from bonds is put in bank, bank lends out cash).

QE split the Smart Money. Some saw it as breaking the edict to kill inflation. (Their view is any printing of money, regardless what you do with it, debases its value, causing inflation. Or in their words, “If you just open the fucking taps, the fucking bathtub will flood.”) But those complaints generally fell on deaf ears, since QE had also stabilized the markets, their jobs, and their wealth. The cash used to buy bonds ended up sitting in the banks, who hoarded it. Which, to some, made QE pointless, and to others, wasn’t that surprising of an outcome. (It’s like a billionaire going out and saying, “Hey, I am going to buy nothing but hot dogs,” and then being surprised when hot dog vendors end up with lots and lots of cash.)

So, if the government was willing to hand out cash, and the Fed was willing to print money, why didn’t it do a helicopter drop? The Fed doesn’t have a clear mandate to give out cash to citizens, which is considered fiscal policy, and that is the job of the elected government, not appointed officials. Yet it’s not a problem that couldn’t be overcome with an aggressive interpretation of the Fed’s role, some clever accounting schemes, and politicians willing to support it. (There is little hope of getting politicians to support it, though. Neither of the current political parties are crazy about cash handouts, albeit for different reasons. The Republicans hate the idea of expanding the role of the Fed or the government, especially when it is to give a certain class of people something for nothing — even if giving out printed cash is really just another form of a tax cut. Democrats, on the other hand, would rather give out targeted cash through complex programs to encourage this or discourage that.)

Roughly thirty-four years after the ascendency of the Smart Money, a period that has seen it acquire vast wealth and power while the rest of the U.S. has stagnated, much of the world faces low growth, zero rates, and little inflation. The Smart Money has started to come to grips that this might not end anytime soon, a possibility they have taken seriously enough to give it a name: secular stagnation.

Four years ago, I quit finance, sick of the whole game. A few months later, after Obama’s re-election, I went out with a group of traders, including my old boss. We ate steaks, drank a lot, and told stories of trades that worked, and trades that didn’t. Many of the traders were drinking away a bad year they had spent betting that the U.S. would blow up, and that inflation would spike. Like Japan, it hadn’t. After dinner, my old boss offered to split his black cab with me. I declined, saying the subway would be faster. He looked at me and smiled, although it wasn’t clear he was joking. “You should wear a mask,” he said. “With that man in power, it is only a matter of time before this country is filled with inflation, crime, and the subways with tuberculosis.”

Things I Regretted Eating in 2015

by Jane Hu

Week-old vegetable stew.

One large SkinnyLicious® sangria, avocado eggrolls, dynamite shrimp, miso salmon, fresh strawberry cheesecake, and a side orders of fries all during the first Cheesecake Factory trip of my life. 2015 was going to be the year, I told myself. I projectile vomited soon after the meal. Were we ever so young?

Last meal I shared with my ex before moving out of his apartment. (I didn’t have much of an appetite. He ate most of them.)

The words said and emails sent immediately after moving out.

Whiskey without the rocks.

All the fun-sized chocolates I don’t actually remember eating at this year’s Halloween party.

Beet hummus. 🙁

One vodka martini (after a matinee screening of Spectre), followed by one glass of white, and far too much Chinese food on Thanksgiving at Oakland’s Shan Dong. I may have vomited afterwards as well.

Oreo Thins.

Illustrations by Becky Clark

Save Yourself is the Awl’s farewell to 2015.

A Small Place for Fugitives

by Jia Tolentino

This year, I shelved a novel that I had been writing since 2010. The last draft I sent to my agent had its moments, but it read inert and youthful, sort of stained with indecision; at any rate, I’d started to think it had problems that neither of us would fix.

At final count, the manuscript was three hundred and six pages and almost seventy-eight thousand words long. There were fifteen chapters, all of which I’d edited several dozen times. In retrospect, that seems sensible — what you’d want to do, when a book was concerned — and also insane, as I don’t remember any of it. Editing is a fugue state; the time self-erases. I’d have forgotten about it altogether except for the fact that the weight of the effort has lifted only gradually, and also, the fact that the evidence is two clicks away: the evolution of an idea from nothing to something to nothing again sits peacefully in a folder named “Novel!” that I dragged off my desktop early in the fall.

Anything that long, you end up in something like a relationship. This one was absorbing and fun and punishing and important; it was naive in a good way, and suddenly incompatible with my life. I had spent hours trying to do well by it: I bound its pages and took it with me on vacation; I talked to it on dog walks and edited in the rain. And, just like a relationship, I think about the next one sometimes. I’ll be wiser, better at it — more controlled and more open and more specific in my hope.

I miss my book sometimes, is what I’m saying. It was a good book — quieter and sadder and more solemn than me — although now I’m trying to tell myself it was dour and awful, because if the book was bad then it’ll be easier to forget about it, and I never want to look at it again.

But writing things off is the exact trap fiction guards against. The form’s great grace is the argument it makes for ambiguity; it fails as soon as a story can be too easily reduced.

We do, too. I have learned this lesson in iterations with the people close to me; I learned it again with the characters in this book. There was a quiet long-distance taxi driver hiding his sexual orientation, and his daughter, an unflappable, antagonistic camgirl, and her nervous childhood friend, all caught up in the effects of a gold mining company scam. The book was set in Kyrgyzstan — LOL, did I mention that yet? — a post-Soviet, syncretically Muslim, rapidly globalizing country in Central Asia that looks like a combination of Switzerland and the moon.

The working title was The Earth Is a Small Place for Fugitives, a translation of a proverb that accretes meaning as technology spreads unevenly, wiring us to person and place. In the Kyrgyz village where I served a year in the Peace Corps, there were cookies shaped like iPhones and no running water; there was dollar-a-liter vodka and anvil-heavy tradition. It seemed a great human constant to try, and fail, to escape one’s own self.

Or maybe everything I thought while I was there was projection. I started the book during my increasingly depressive off-hours between shifts teaching at the tiny village school. I knew that writing about the country was hubristic — but then writing is, in general, and I was twenty-one. I spoke the language, anyway, and it’s hard not to mistake words for knowledge. In service of understanding, they kept tumbling out.

In country, I wrote out of pure compulsive behavior. When I got home to Texas, I kept at it because I was sad, and bored, and couldn’t stand to write about myself. I applied to MFA programs to see if what I’d written was worth anything, then I moved to Ann Arbor because it was worth at least that stipend, then I signed with my agent to see if I could write a decent book. Once I did, which happened around when I moved to New York last October, then I didn’t know what to do. The book was decent. What else had I ever wanted? “Oh,” I realized, after a very odd summer. “Why didn’t you try to write something fucking good?”

My answer to myself was that I couldn’t have. I write to find the limits of my ability to understand things, and I found them this summer — on a project with a difficult premise, which I started before I knew I could write. But I have a goldfish memory and an inability to sustain cognitive dissonance. I feel so certain of some stories I tell myself until I feel certain, suddenly, that they are lies. Seen another way, this sequence seems suspicious. Who spends five years on a book out of curiosity?

It’s not the giving up that bothers me. Everyone has a drawer novel, a stretch of being religious, a longtime boyfriend now farming psychedelic mushrooms in Berlin. What bothers me is that I keep forgetting this isn’t the first novel that I’ve put to bed.

That other story begins in 2009, the year I graduated from college, pragmatic and scrappy from the recession. In the months I spent waiting for my Peace Corps departure, I tried out an idea that I thought could sell. The vibes, I’d say, were “ersatz J. Courtney Sullivan.” I plotted a story that would take place over the course of one summer, starting with four girls biking along the Hudson River on a bright, hot, blue day. A plane crash-landed just as one of them confessed something startling, and the emotional plot clock started to tick. The characters were roughly based on me and my three best friends from college. There were two embarrassing epigraphs. The novel, if you will literally believe it, was called Girls.

Thankfully, I am spared the evidence of myself, because about a hundred and fifty pages into the draft, I lost the entire thing. I kept working on the manuscript when I got to Kyrgyzstan, and then my backpack was stolen out from under me at an internet cafe when I was Skyping my boyfriend. I watched the security camera footage — two men pick it up and walk away.

To continue the relationship metaphor, the loss was a violent kind of breakup. I felt hollow and panicked and insane and I cried all day. My friends took me to the police station, combed the secondhand markets, bought me beers, and in the nicest thing anyone’s ever done for me, one of them even lent me his laptop; he knew that I needed to write to get out of my head.

I did, on a blog now set to private. And I went back, finding an entry from November 2, 2010.

There’s a line in “The Rabbit Hole as Likely Explanation” by Ann Beattie: “You think you understand the problem you’re facing, only to find out there is another, totally unexpected problem.”

Since college, when I started studying writing, I haven’t been able to get around the wall of artificiality involved in relating a story — particularly one belonging to a person you make up yourself. My professors (including Ann Beattie) elide this completely in their own work, but I often feel like a little girl designing a wedding dress when I try to write fiction. How can you write into the base level of what constitutes an experience and make it true?

The thought eventually slipped into the way I conceived of my life, and it does so even more in Kyrgyzstan. Here I’m alone most of the time and must relate things with the idea that the telling has a point. I can tell you that a man pushed me into a taxi telling me he was going to make me his wife, but why would I? Only because it sounds like a good story. It sounds different than what it felt like: a hangover, a cloudy day, a dirty man wearing a leather jacket, something that registered only as dull, sad annoyance.

Still, like a liar, I like to shape things, and I like to write. Last fall I started a novel that I had gotten deep into by this point, a year later. I’m a tough sell but I was beginning to think that my book was decent, that I could eventually get it published. Then last weekend, two men stole my laptop while I was Skyping at an Internet café in the capital city.

I have excuses for not backing up my work, but they’re just excuses. Here’s where the artificiality kicks in: I can say that I’m devastated to have lost all that work, which is true, and that I lost book reviews and grants in progress and a dozen small projects and teaching tools, which are all true statements as well. I can say I’m writing this because I want to explain why I am letting this blog slip.

But you think you understand the problem you’re facing, only to find out there is another, totally unexpected problem. This is a theme of working for Peace Corps. You have a hard time understanding where your priorities should lie, what your perception of an event should be. You’re constantly creating a narrative for yourself that keeps derailing under these unexpected problems. You thought work would be hard until you realized you have to create the infrastructure first. You need to brush your teeth, but first you need to haul some drinking water, then you find that the well is dry. You think your language will be inadequate to speak to the police about your recent theft, then realize they only want to talk to you about your love life anyway.

You think the biggest problem will be rebuilding your novel, only to realize that you are barely capable of telling a story truthfully. In this I have somehow managed to make it appear that life is hard for me, as if that’s what was important.

The first week I got to my village, a drunk man threw a baby against a metal gate and it died. A month ago, my bus hit a person on the road and didn’t stop. Two close friends of mine (one of them a girl) were beat up on the street after leaving a club. Last night in my village, a drunk driver ran over a person on the street and in the resulting fight two more men were killed. The word for “woman” in Kyrgyz is the same as “wife” and there’s a wife down the road who always has a black eye. When I complained to my twelve-year-old sister about a man grabbing my crotch, she sighed and said, “Yeah, Kyrgyz men are like that.” There’s been a funeral in my village every day for weeks.

You think you understand the problem you’re facing, only to find out there is another, totally unexpected problem. What a minor tragedy, losing a manuscript that you know was sophomoric. What a major travesty, to be in the middle of all this and only be able to know your own story. Still I don’t think I can help being sad about this. I have enough trouble convincing myself that I can actually write without losing the first real thing I’ve ever written. And like all problems in Kyrgyzstan, it exfoliates outward endlessly, magnified and connected to sadnesses that I have no right and every right to feel.

I’m already telling myself that it’s better I lost my half-finished book so that I didn’t waste any more time on what I’ll call a warm-up exercise. That is not true at all, but I’ll probably believe it within a week. The mind can do easily what the author cannot. The story is done with, and like all the best ones, it makes me feel better about myself — which is always proof that it’s leaving too much out.

I shelved my second novel out of certainty that my writing had developed, that my instincts had gotten better, that as time went on they’d continue to. I suspect, reading this, that I am under some illusions, which I nonetheless hope to maintain my entire life.

The use of a year as a bounded unit is that, at the very end of it, you feel changed. You’re molting. You can identify what has exhausted you and what has made you hopeful; you know what you’ve clung to and what you’d like to leave behind.

A book, as a unit of focus and devotion, can function in the same way. Here, I am forcing myself to admit how thoroughly the second book was a reaction to the first one, which was itself a reaction to a problem around identity, a concept in which principle and projection seem almost reversible, in which there are shifting distances between how you see yourself and who you really are. I have been too uneasy about the “write what you know” edict; I have looked for too many ways around representation: who you want to write about, which means who you are writing for; the question of whether your eye reduces experience or enlarges it; the burden of this translation, and the gift.

To be less abstract about this: When I wrote that first book, I tried to pad it out with things that I thought people found appealing, which meant New York, money, status, anxiety, sex. (I had no money, had never lived in New York, and was celibate/shitting in an outhouse.) I was bad at writing about those things, but I thought they were “universals,” or would pass as such, and would help the book sell eventually. Very specifically, I wonder — and I would be so sad to have done this — if I ever took a look at the horizon and decided to make all the characters white.

But I can’t go back and I can’t look and I certainly don’t remember. Five years after I lost the first book, even the girls’ names escape me, and just months after the second one, I can barely recall how I felt while writing it — only how I felt when it was gone.

Photo by Thomas Depenbusch

Save Yourself is the Awl’s farewell to 2015.

The Humbling and Inspiring Tale of the Game That Proved Hitler's Name Is Still Worth at Least A...

The Humbling and Inspiring Tale of the Game That Proved Hitler’s Name Is Still Worth at Least A Million Dollars

by Rob Dubbin

You probably know about Godwin’s Law, which states that as an argument escalates, it becomes more and more likely something will be compared to Hitler. The idea seems almost quaint now, when fascism makes headlines and snakes its way into every political argument, Godwin constantly poking his head into frame with a cardboard cutout of Hitler, waving it around for attention.

Some months ago, I was invited — very excitedly by a game designer I respect — to play a new game, a work-in-progress even, called “Secret Hitler.” If you have played Mafia or Werewolf, it’s a party game like that, where people divide into factions and trade hidden information to expose each other. They’re all games where you can sort of performatively be an asshole to your friends — lie to their faces, manipulate them against their own interests, “evil” type stuff that is mostly okay as long as everyone feels real-world safe.

At the time, I knew Secret Hitler shared a designer with Cards Against Humanity, the game of politically incorrect sentence completion so wildly successful that it spawned a whole cottage industry of large-scale marketing stunts. This very winter, Cards Against Humanity mailed 8 nights of Hanukkah presents to 150,000 customers who’d paid $15 each, including a 1/150,000 share of an original Picasso. Everyone who bought in — I’m one of them — gets to go to a special website and vote on whether the framed sketch is donated to a museum, or laser-cut into 150,000 pieces. However we vote: It’s an impressive feat of logistics, driven by a keen sense of how to manufacture outrage and generate publicity.

Even with this context, the title “Secret Hitler” extended something of an aggressive invitation. It’s endemic to the Mafia/Werewolf game genre that whoever the bad guy is, someone has to pretend to be that person. I’ve never been particularly comfortable getting into the mindset of a secret gangster or werewolf, but next to Hitler they both seem to offer a pretty chill headspace. It almost surprised me how quickly I declined to play this game, leaving the party pretty much in that same sequence of motions. Then I forgot about it.

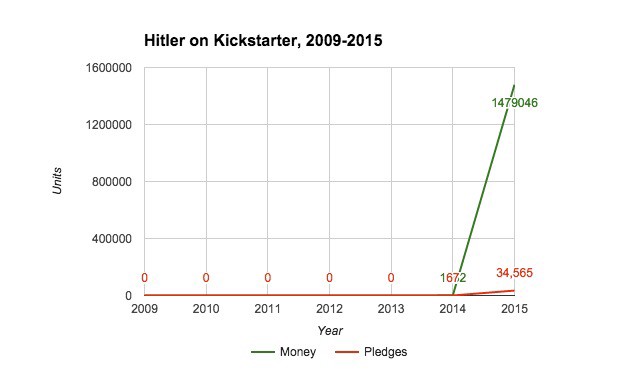

…Until a month ago, when Secret Hitler launched a crowd-funding campaign. Its goal was $54,000, but it crossed the finish line with nearly $1.5 million in pledges. Which do you think is better, looking at it like the Hitler game got a lot of money, or that it got a lot of pledges? Either way, 2015 was a banner year for Hitler on Kickstarter:

(Note the massive year-to-year increase over 2014’s successfully funded “Killing Hitler With Praise And Fire Choose Your Own Path”)

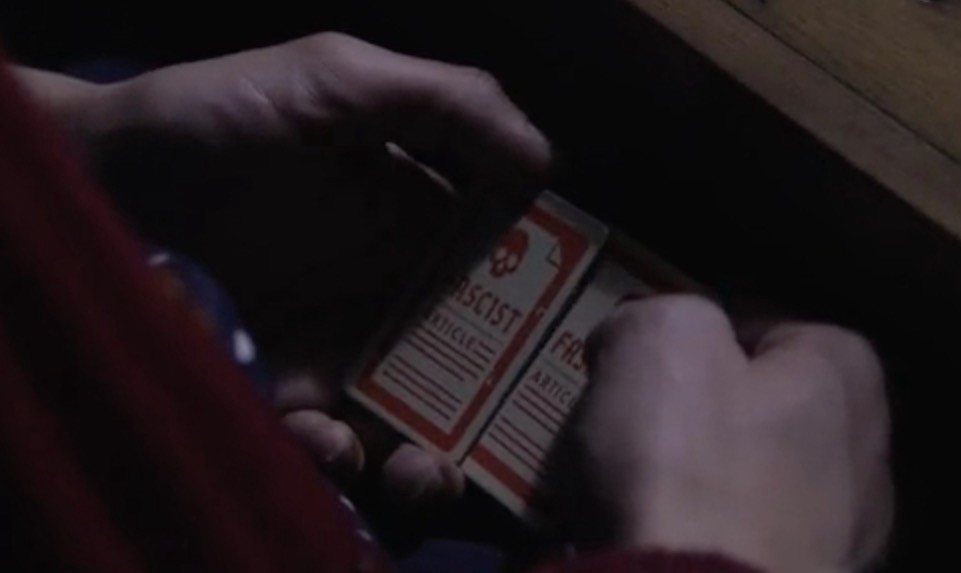

Did you know the Nazis had a style guide? All kinds of stuff in there: logos, uniform standards, just some really tight overall branding. Typefaces. It’s all done up in this kind of angular, Teutonic lettering that makes a goddamn heck of an impact. It lives here, and I understand if that’s not something you want to click on or experience. For me, it helps that I can’t read German.

You could also check out some dope Nazi typography on the Secret Hitler Kickstarter page, where it’s everywhere. In the campaign intro video, on the cards, and all over the page as pre-rendered images, because I guess modern browsers don’t ship with Reich-standard fonts. You’re not gonna lose me just for using these symbols, I’m all for evoking a time and a place. But they printed endorsements with it! If I had tested this game, and in good faith given its designers a positive blurb, and they printed it in the Nazi font on their website — well, did you do that? If so, how do you feel about it?

I’m not a prude about using Hitler’s name. I believe it should be known. But I also believe his name has power, and have consistently felt an immediate wrongness around how Secret Hitler has deployed it. There should be a high bar for invoking this person, and there should be such a thing as falling well short of it. I wonder if someone walked into a US Trademark office and sheepishly filed these papers.

The people who made Secret Hitler advertise it as a playable psychological model of how totalitarianism takes root. Their sales pitch also reassures that the game “doesn’t model the specifics of German parliamentary politics.” Which makes sense: just as all art must draw some line around reality, so did Secret Hitler’s designers pick and choose from the horrific totality of actual-Hitler’s work, isolating just the right parts to weave into their party game. You don’t want to bum people out with this stuff.

Of course, it’s also a laudable goal to want to make people sensitive to fascism, and the dynamics that can help it along. Here are a few to watch out for. One is desensitizing people to fascism’s consequences. Another is to reframe its historic perpetrators as little more than mascots and thematic bunting. A third way to make fascism seem appealing is to demonstrate its remarkable ability to move units. As a game, Secret Hitler claims to be about subverting the mechanisms of tyranny. As a marketing campaign, it seems to rely on emulating them.

At best, Secret Hitler is a clever and enjoyable party game wrapped in a ghastly skein of totalitarian semiotics, with one of the most infamous names of the 20th century attached like a warhead to the title. It’s designed to shock, and obviously with me it succeeded. It’s possible this whole thing just has you thinking “Fuck yeah, Secret Hitler, I know exactly what we’re doing on Ryan’s bachelor weekend now.” The Kickstarter has already concluded in triumph, and Secret Hitler will forever pair with Cards Against Humanity in countless duffel bags.

To be clear, I don’t challenge this game’s existence. Hitler’s agenda targeted every Jew, and so it is every Jew’s birthright to make whatever garbage they want with that legacy. The design team has already taken their shot at the critique that Secret Hitler is gross, announcing a set of stickers that will ship with the game for anyone who’s offended or would like “to pretend that historical figure Adolf Hitler didn’t exist.” So you can rebadge your copy with Trump, or South American Junta Mustache Guy, or Santa Claus. This sweaty attempt to satirize the offended is laced with the anxiety of having committed to doubling down on an aesthetically bad bet.

The deepest irony is not that this game will become a financial success while dwindling ranks of present-day Holocaust survivors tread water at the poverty line. That’s less of an irony and more of a melodramatic truth. The deepest irony is probably that Santa Claus sticker. Because: Could these exact rules have been called “Secret Santa” and tracked a cutthroat St. Nick’s brutal rise to power in a gritty, prewar North Pole? Certainly. Would that have been a better game and a better joke? I say yes. But would it have sold as many copies? Not a chance.

Save Yourself is the Awl’s farewell to 2015.