Albrecht La'Brooy, "Pavilion"

Yeah, I get it, it’s cold. Guess what? That’s what happens in January. For now. I bet you’ll miss it when you’re running from fires. Which you will be soon enough. Try to appreciate what you have while you still have it, I always say. Anyway, enjoy.

68 More Fantastic British Names Gathered While Watching BBC Credits Over the Years

by Mikki Halpin

1. Pooky Quesnel

2. William Postlethwaite

3. Vivian Ackland-Snow

4. Tussy Facchin

5. Tim Piggot-Smith

6. Tabitha Peacock

7. Sarah Wormbescher

8. Sandrine Mugglestone

9. Ross Onions

10. Phoebe Waller-Bridge

11. Clinona Harkin

12. Philippa Broadhurst

13. Peregrine Andrews

14. Patrick Ryecart

15. Olivia Sangster-Bullers

16. Holly Bowcott

17. Geraint Morgan

18. Oliver Cockerham

19. Martin Chitty

20. Barnaby Papworth

21. Christine Walmsley-Cotham

22. Maeve Dermody

23. Leila Mimmack

24. Kayleigh Cruickshank

25. Harriet Beasley

26. Patrick Malahide

27. Fern Deacon

28. Hannah Gawthorpe

29. Oriel Bathurst

30. Graham Headicar

31. Dominic Threlfall

32. Graeme Wetherston

33. Kit Hesketh-Harvey

34. Gillian Dodders

35. Fiona Button

36. Jo Fernhough

37. Finbar Hopson

38. Daniel Dewsnap

39. Eve Wignall

40. Dylan Raw-Reiss

41. Dash Lilley

42. Lucie Ponsford

43. Dan Whybrew

44. Charles Bodycomb

45. Beaumont Loewenthal

46. Abigail Cruttendon

47. Pip Donaghy

48. Abi Nettleship

49. Daniel Wombwell

50. Damian Butlin

51. Nigel Venables

52. Teague Bidwell

53. Claire Porrit

54. Gilly Poole

55. Hugues Mace

56. Darcey Martindale

57. Alleyne Kirby Davies

58. Emeline Tedder

59. Morven Christie

60. Declan Brophy

61. Burn Gorman

62. Claire Pidgeon

63. Ussal Smithers

64. Hamish Doyne-Ditmas

65. Oonagh Bagley

66. Linden Brownbill

67. Crispin Layfield

68. Finn Mccleave

Previously: 68 Fantastic British Names Gathered While Watching BBC Credits Over the Years

New York City, January 3, 2016

★★★★ The air through a briefly opened window was mild enough to serve as a call to go outdoors, which even the children were willing to entertain. The sun coming up the avenue was noticeably warm. In the cross-street shade, the wind whipped at the trash bag around a Christmas tree, but the playground was still washed with sunshine. As the children rode their scooters, the shadow of the apartment complex spread up the asphalt relentlessly and not slowly. When noses ran, there was a tissue in the adult’s coat pocket. What were not in a coat pocket were the four-year-old’s gloves, when he decided his hands were getting cold on the chains of the swings. He chose to keep clutching the metal barehanded. By the time he was cold enough to leave, the light had retreated all the way to the gate.

In Between Spaces

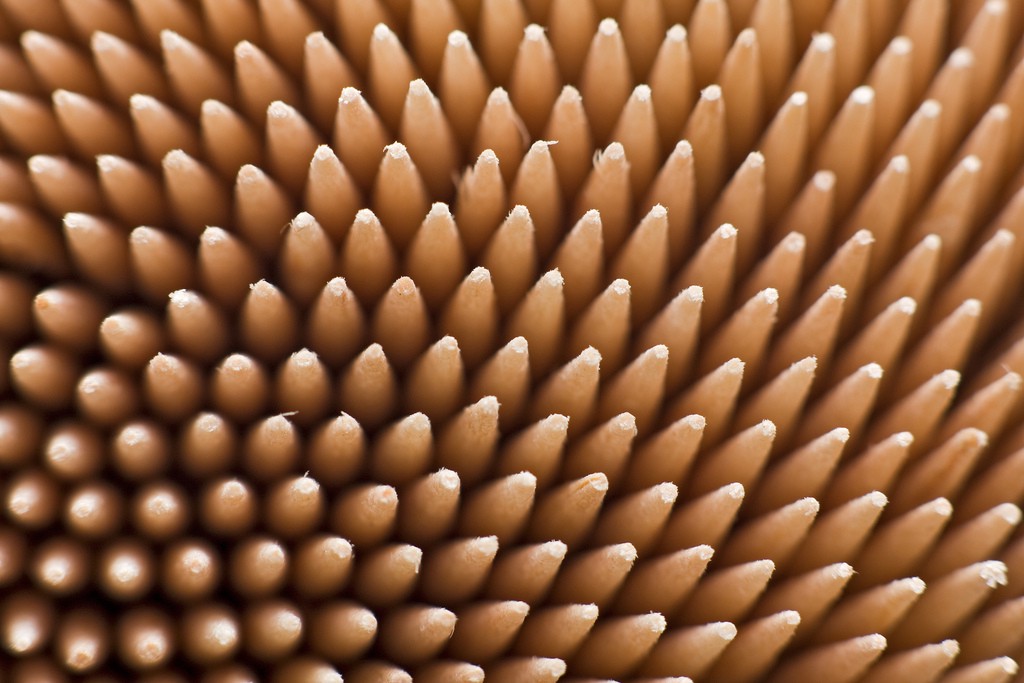

Several years ago, on a warm summer afternoon, I was handed what appeared to be a standard-issue toothpick. I had just eaten a plate full of Hunan-style cumin lamb and I was sleepy. My mouth was tingly and cuminy. I remember this moment particularly well because of what happened next.

An outrageous, aggressively fresh sensation followed. The chilly tingle combined with the cumin tingle to create an overwhelming, ultimately painful feeling in my mouth. I removed the toothpick and stared at it. My lunchtime companion, Paul, the pick pusher, dramatically removed a plastic pack from his pocket and rattled it mischievously, then presented it to me. The pick was an Australian “chewing stick” infused with tea tree oil. I made note of this, popped the pick back into my mouth, and rode the tingle out until it subsided into a nice fresh sort of buzz. Later on, I bought a pack of picks of my own.

I did not get too deeply into the toothpicks until years later, after moving to Los Angeles. The problem with toothpicks and tooth picking, I’ve found, is that there is but a small window in which it is okay to have a pick in your mouth, and that is for approximately ten minutes post-meal, when it’s necessary to needle stuff out of your teeth. Unless you are Steve McQueen — not the director, but the actor, who is dead — if you walk around with a toothpick in your mouth trying to look cool, you look, instead, like a prick.

Los Angeles presented a different situation. The essayist David Ulin has written that “this is a city where the most basic cornerstones are understood to be private — private life, private architecture,” to which I would like to add: private car time. Tooth picking time. I pop a pick when stuck in traffic, or slaloming through downtown, or pretty much anytime I am alone behind the wheel and not singing along to something. Carefully, I work the pick, masticating it until it is frayed and turned into something more brushlike at the business end. Then, I brush my teeth with it. This is the best part, after the mouth tingle: when the pick has turned brushy, when one tool has become another. It’s in these moments, stuck in traffic, crawling through the endless anonymous, unremarkable space, that it seems as though time is both slowing and speeding up. That is, the pick project helps to pass the time, so there it goes, but also, dwelling on the minutia of the pick, pausing within the moment, savoring it, time slows. Frankly, it calls to mind Aboriginal dreamtime, often described as time out of time. Time can be slowed and sped up and sometimes it can even stand apart from itself altogether. Maybe the way a toothpick is also a chewing stick and a toothbrush too. Something like that.

Usually, within this moment, I search the space around me, outside the car. This surrounding space is routinely, almost aggressively boring. I love it. Rebecca Solnit, in one of my favorite essays ever written about LA, calls these regions on and around the road “drably utilitarian spaces.” Their ubiquity, she writes, is “in part because cars demand them, and it is a city built to accommodate cars. These spaces tend to be grey, the grey of unpainted cement, asphalt, steel and accumulated grime; and they tend to be either abandoned or frequented by people who are also discards, a kind of subterranean realm hauled to the surface. Or not.” Or: yes, yes exactly. LA is hell with mild weather.

What I like most about this notion of a subterranean realm hauled surface-ward is the sense of infrastructure laid bare. All the secret things, the in between things, the things that are supposed to simply exist and make our lives easier without thinking about them until they stop working or flood the bathroom, these things are just there, sitting by the side of the road, squat and duller than brick. There is even, on my drive to and from the airport, an oilfield. “The world seems to be made more and more of stuff we’re not supposed to look at,” Solnit writes, which is certainly true, but most things we’re getting so good at covering back up. So much of our technology is wrapped in sleek pieces of plastic or metal that we’d never dream of opening up and are even warned against ever opening. And so many of our things have been turned into, either through marketing or engineering or both, complex pieces of technology. Most people would rather not look at this stuff too closely, anyway. That feeling, of disgust, or boredom, or horror I’m told people get when seeing the insides of things they don’t normally see, that is exactly the thing that I like, maybe most of all.

One day, sitting in traffic and picking away, staring into the murky ceiling of a highway underpass, I turned my thoughts inward, towards the pick in my mouth, an ancient piece of technology. Even the use of tea tree oil was old: Aboriginal Australians crushed the leaves up and used them in healing poultices thousands of years ago, and still do so today; they also burn the leaves and inhale the smoke, and bathe in lakes infused with the leaves. I decided to get a hold of Kate Hammer, a researcher in the school of pathology at the University of Western Australia, in Perth, who studies tea tree oil. When I called her, she told me straightaway that she never had, and never would, stick a tea-tree-infused toothpick into her mouth. “I am not a huge fan of the taste,” she said. The only time she might be driven to dab a little tea tree on her gum is when she’s got a nasty canker sore.

All the Americans she knew enjoyed chewing gum, she said. Why was I so into these toothpicks? In my mind, I began to explain my traffic and toothpick routine, but thought better of it and just told her I was a journalist, working on a story (which is often my excuse for weird questions or behavior or being somewhere I’m not supposed to be). Hammer then explained that what made tea tree oil so tingly was its turpins — chemicals that, among other properties, are drawn to fat but not water. They’re drawn, specifically, to the fatty membranes of bacterial cells. “If the bacterial cell is a bit like a balloon,” she said, “the turpins sit inside it until it becomes leaky, and the bacterial guts leak out, and the bacteria cell dies.” Those tiny explosions of freshness in my mouth were the trigeminal deaths of a thousand bacteria?

“No, it’s more like millions,” Hammer said. Later that day, long after our call, I went for a drive through the hellscape of LA. It was evening, the sky was pink and purple, the ugly infrastructure was silhouetted black or fallen into shadows, disappearing completely. I put a pick in my mouth, allowing it to soften, then bit down enough to release a burst of tea tree oil, and thought of the bacterial apocalypse I had unleashed. It was satisfying. I lingered at a stoplight, chewing slowly, murdering millions of mouth bacteria while the light went green and the driver behind me began leaning on the wheel and only then, with the drone of the long honk behind me, did I begin to speed up.

Khotin, "Baikal Acid"

Was last night the worst case of Sunday Dread you’ve had in a long time? You are not alone. The good news is it probably won’t be that bad again for a year. Which is not to say it won’t be bad, just not that bad. Eh, what are you going to do? Anyway, while you’re digging out and getting back into things you can listen to this, and if you’re looking for the occasional distraction you can dip into any of our year-end essays that you might have missed. Our gratitude and admiration go out to Carrie Frye, Rachel Monroe, Kevin Nguyen, Laura June, Lindsay Robertson, Bijan Stephen, Casey Johnston, Ryan Bradley, Rob Dubbin, Laur M. Jackson, Jia Tolentino, Jane Hu, Jenna Wortham, Emma Carmichael, Katie Notopoulos, Maria Bustillos, Paul Ford, Max Read, Leah Finnegan, Jazmine Hughes, Jacqui Shine, Rick Paulas, Helen Rosner, Dayna Evans, Bex Schwartz, Brian Feldman, Leah Reich, Johannah King-Slutzky, Jason Parham, Jo Livingstone, Matt Siegel, Silvia Killingsworth, Vinson Cunningham, Betsy Morais, Meghan McCarron, Cord Jefferson, Brendan O’Connor, and Maud Newton.

The Year That Time Collapsed

by Brendan O’Connor

Sometime around February, a friend introduced me to a Japanese iPhone game called Neko Atsume. It involves cats. I say that it’s a Japanese game because it appeared to be for Japanese people, or at least people who speak Japanese, given that it was entirely in Japanese. As with real cats, you don’t have to do much: Make sure there is food in the bowl and pillows to sit on or boxes to sit in; unlike real cats, however, Neko Atsume cats give you money to buy them things. Sometimes they bring you gifts — real cats do this too, but it’s usually something gross like a dead animal or a hairball. The game cats bring earrings and cicada shells. It was a simple premise, and it’s also addicting. The point was never clear. For about a week after I first downloaded the game, I would wake up, feed my real cat, clean her litter box, and then get back into bed and play with my Neko Atsume cats.

In the future, I will remember 2015 as the year that time collapsed. I have been working, essentially, seven days a week since last December, having been offered a weekend gig that, after about ten months, turned into a weeknights gig.

Without lengthy, consecutive breaks in which to do something other than work, I started losing track of what day it was. If I took a day off it was often out of either necessity, or by accident, or both: I would wake up and waste a morning and then decide that I needed a day off. Maybe it was a Monday, or a Thursday. Ostensibly my day off was Friday. It never seemed to work out. This experience has only accelerated since moving to nights. It’s a good schedule really: six-ish to midnight-ish, unless there’s breaking news. It offers plenty of time to do other freelance reporting and writing during the day (theoretically, at least), so long as I actually get out of bed don’t have any other errands to run or chores to take care of.

(If I believed that the world reflected my inner life, the fact that, at least in New York, we have had such a mild winter, which followed a very mild summer, would seem to be an externalization of this temporal smushing. But I don’t believe that. The weather is just the weather. Let’s not be ridiculous.)

Anyway, despite waking up and not knowing what day it is and growing more gray hairs in the past two months than I have in my past twenty-six years, the schedule shift has been, on the whole, good. I’m making more money!

In March, the New York Times reported that Netflix was expected to spend more than $450 million on original programming in 2015, up from $243 million in 2014. Next year, Bloomberg reports, Netflix expects to spend $5 billion on programming altogether — both original programming and that which it licenses from other producers.

From Jonathan Crary’s 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep:

A 24/7 world is a disenchanted one in its eradication of shadows and obscurity and of alternate temporalities. It is a world identical to itself, a world with the shallowest of pasts, and thus in principle without specters. But the homogeneity of the present is an effect of the fraudulent brightness that presumes to extend everywhere and to preempt any mystery or unknowability. A 24/7 world produces an apparent equivalence between what is immediately available, accessible, or utilizable and what exists. The spectral is, in some way, the intrusion of disruption of the present by something out of time and by the ghosts of what has not been deleted by modernity, of victims who will not be forgotten, of unfulfilled emancipation. The routines of 24/7 can neutralize or absorb many dislocating experiences of return that could potentially undermine the substantiality and identity of the present and its apparent self-sufficiency.

Some people — presumably those who don’t speak Japanese — don’t like that they don’t understand what’s going on in the Japanese cat game app. When the game started getting popular with English-language users, for example, the comments in the App Store were kind of amazing.

“I love this game. It’s very cute and fun to play,” wrote Lily Baby 18. “I only have one problem. I wish you could change the language to understand what’s going on. If there is a way to add other languages, that would be great.”

“The cats are so cute,” wrote nichAsun. “But please add English.”

As far as I was concerned, this is did not detract from the experience of playing this game, but enhanced it. The point was never clear; there didn’t seem to be a way to win. If there was, it was secondary. Everything that happened was a mysterious surprise: the game was mostly inscrutable, with occasional glimmers of causality.

I have a theory about Netflix: It does not mean anything for television to be “good” anymore.

I try to be a critical, skeptical person — especially of that which appeals to me. But this year I spent so many hours watching (and enjoying) television shows that I thought were “bad.” Many of Netflix’s original shows are eminently watchable, but they are, looking at them with anything resembling discernment, not actually good. Marco Polo is extremely bad. Peaky Blinders (not a Netflix original, but they acquired the exclusive distribution rights for the United States) is extremely bad. Sense8 and Narcos: extremely bad. All of them I watched in their entirety in a matter of days. It’s not just Netflix, either. Or maybe this is The Netflix Effect, and it’s echoed back up into legacy programming. In any case, nobody actually cares about the quality of the final season of Mad Men or who is dead and who is alive on The Walking Dead. Prestige television is a sham. Nobody cares. They just want to get it over with.

Again, this is all just a theory. I don’t know if I really think any of this is true. But if consumption is compulsive, then it doesn’t need to be compulsory. And compulsive consumers will always come back, whether they want to or not. They don’t have to be convinced.

I have not been an avid player of video games since I was very young, but, a few weeks ago, a friend introduced me to Skyrim, and I connected with it in a way that I haven’t with a game since Ocarina of Time. This was an entire world, full of countless stories and adventures, puzzles and fights. Dragons! I watched her play for hours. Then I made my own character, and I played for hours. A week later, at her apartment again, I played even more. I decided that I needed my own Xbox, so I bought one on Amazon. It was an impulsive decision.

The console came a few days later, and in the box was also a first-person shooter. I installed it, played it, and did not like it. For one thing, the on-screen bloodshed made me queasy. For another, in contrast with Skyrim, all the choices are foreclosed. It’s not necessarily easy, but it’s straightforward, barely more complicated than watching an extremely violent, poorly scripted movie.

As much fun as I am finding Skyrim, though, I have to admit that this is a difference of degree, not kind. You’re in their world. There are many choices to make, but they remain choices constructed for you. The game’s intoxicating freedom ultimately proves illusory, although by the time you realize this you’re already hooked. I’m not claiming to be breaking new critical ground here or anything, but it’s really no wonder this is a $90 billion industry.

The other day, after a few months of not playing, a friend opened Neko Atsume on her phone. It was in English, now, and all the cats were gone.

Save Yourself is the Awl’s farewell to 2015.

Best of Luck

I remember telling a girl I dated in college once that I’d like to be dead by fifty. It was an egregiously stupid thing to say, the kind of low-risk rebellion a teenager from the suburbs engages in to seem dangerous and irreverent, like smoking a joint or shoplifting or wearing eyeliner (all of which I have also tried). I said it with a sly smile, which only got bigger with her protestations. “Why would you say something like that?” she asked. She seemed slightly disturbed, the response I was going for. “This world is trash,” I said. “Who the hell would want to live here for a long time?”

As was the case with a lot of the stuff I said back then, I didn’t know what I was talking about. I did believe — and still do — that the world is awful in many ways. But I knew nothing of death. I’d never had anyone close to me die. Save for a back surgery my dad had when I was ten, I’d never even visited a hospital for anything serious. The only funeral I’d attended was for a good friend of my father’s who drank himself into the grave after his wife left him. It was a Jewish service. As people surrounded the family to offer their condolences, I saw the dead man’s young son smile for a moment. I still think of that smile a couple times a year, like a childhood riddle whose answer still eludes me.

I spoke flippantly of death — and falsely longed for it to impress girls — because I really knew nothing about death. Of course I knew it happened, but it was so far away and inconceivable as to be ignored, like the outer reaches of space.

One day in August, ascending the stairs to my apartment after returning from the gym, I almost passed out. My vision went spotty and dark the way it does after looking at a camera flash, but not before I looked down to see my chest rapidly pulsating with my heartbeat. I scrambled to unlock my front door and ran to the couch to lie down. After a few minutes, the vertigo went away and my vision returned, but my heartbeat stayed fluttery and rapid. When I finally stood up and looked around, I noticed that in my haste I’d knocked over a stool and forgotten my keys in the door.

It was a hot day and I felt dehydrated. I’d spent a couple hours at the gym and I live at the top of a five-story walkup. To me, the signs pointed to a case of overexertion, so I decided to drink a lot of water and sleep it off. After going to bed at around 11, I woke at 3 A.M. with the sound of my heart pounding into the mattress and vibrating up through the pillow into my ear. I turned on a light and briefly considered going to the emergency room. I nixed that idea because then, by definition, I would be having an emergency, and I didn’t have emergencies. I had minor problems and I drank water and slept them off. Going to the emergency room would have forced me to reevaluate everything I thought I knew about myself. And so I googled to see when Mount Sinai’s Brooklyn Heights urgent care opened. I then spent the next five hours tossing and turning in bed, berating myself for all the stupid decisions I’d made with my health over the years, the garbage I ate and drank and smoked, all the while confident that death was like space, confident that I would never walk in the darkness of either.

At urgent care, a gentle nurse wearing tinted glasses and a thick gold chain over his scrubs calmly checked my blood pressure and put a cold stethoscope to my back, sending goosebumps down my arms. He dotted my torso in electrodes and administered an EKG. Before he left the room, he said, “Best of luck to you.” My stomach sank at that: “Best of luck.” It’s what someone says when they’re not sure you’re going to be O.K. A few minutes later, a physician came in and told me that I was experiencing what’s called atrial fibrillation. Though I was sitting still, my heart was beating erratically at a rate of a hundred and forty-two beats per minute. “That’s how fast it should be going if you’re running a marathon,” the doctor said. She told me she wanted to call an ambulance to take me to Mount Sinai’s cardiology center on the Upper East Side.

“I took an Uber here,” I said.

“You’re free to do what you want, “ she said, “but this is more serious than an Uber.”

I acquiesced and they wheeled me out of the building on a gurney. As I rolled past the nurses’ desks a couple of them turned to me. “Best of luck,” they said.

The ride to the hospital was one of the more surreal experiences of my life as I sat awake, lucid, blasting through New York City across the Brooklyn Bridge and down the wrong way on one-way streets with a siren blaring overhead. On the thirty-minute trip, I finished reading the last two pages of Slaughterhouse-Five, a book I’d often chastised myself for not reading sooner. Billy Pilgrim’s predicament, being “unstuck in time,” resonated deeply in that moment. In an ambulance, an E.M.T at the ready if I were to begin dying — maybe I already was dying — my mind wandered scattershot to various eras and people in my life: A cruel thing I’d said once that I might never be able to take back now. My mom singing to me. A girlfriend I’d once had. I’ve heard she works near the Brooklyn Bridge these days; maybe just then she was on the phone making dinner plans with a new boyfriend, maybe she had to pause for a few seconds to let the siren pass.

At Mount Sinai, they attempted to slow my heart rate with an IV drip of a beta blocker. When that didn’t work, my heart began to race even more. There is a comedic cruelty in trying to steady your pulse as doctors and nurses swarm you, stabbing you with needles and asking if you smoke crack. After a couple hours, they told me they were going to try a cardioversion, a procedure in which they stop your heart momentarily and then shock it back into rhythm. “Turn it off and turn it back on?” I asked. “Like an old laptop?” “Kind of,” said the nurse, offering a weak smile. As she pulled shut the curtain to my bed she said, “Good luck.”

The doctors said that sometimes a cardioversion can result in “complications.” For instance, a cardioversion might dislodge a blood clot hiding in your heart and lead to a stroke, which in turn can kill you. I figured I should let some people know if there was a greater-than-usual chance I could die soon, and so I called my mom. I’d avoided calling before so as to not worry her, I said. “Don’t shut me out of your life and tell me you’re doing me a favor,” she said. Next I texted my friend to tell her that I was in the hospital and I dearly appreciated her friendship. After that, I cried silently for a couple minutes.

The last thing I remember before the cardioversion was the anesthesiologist saying, “This is only going to take a second, but you do not want to be awake to feel it.” When I came to, my heart was back to a normal rhythm and there was an electrode burn on my sternum about the size and shape of a deck of cards. It lingered for weeks, scabbing over and itching and reminding me of the time they powered me down.

They sent me home that day with blood thinners and a beta blocker, which I took daily for three weeks, shaving and walking carefully lest I cut myself and “bleed to death all over the freakin’ place,” according to one doctor. I started drinking a lot of juice and eating more foods rich in omega-3 fatty acids. And then, two months after the first attack, as I exited my favorite smoothie shop on my way into work, it happened again. I took a big sip of my Protein Buzz and gasped as I felt my heart quake and fall into an erratic staccato rhythm, like a jazz drum solo. I went to work and waited to see if things would calm on their own. When they didn’t, I hailed a cab to see my cardiologist, who prescribed an anti-arrhythmic pill. An hour later I was back to normal. Today I keep a troika of beta blockers, blood thinners, and antiarrhythmics lined up neatly on top of my dresser, sentinels in the fight against my own heart.

My cardiologist tells me atrial fibrillation isn’t life threatening: It’s common, and that I could live a happy and healthy life for several decades with little management other than exercise, healthy eating, and taking medication as necessary. He tells me I should take steps to “chill out,” so I’ve signed up for therapy and piano lessons. (When they fall on the same day, I walk into my counselor’s office with “Row, Row, Row Your Boat” stuck in my head.)

I accept most of the doctor’s opinions at face value, but the heart isn’t a gallbladder or even a limb. The heart is foundational. The heart is a linchpin for life, and mine is jittery. Flying home for Thanksgiving last month, I felt myself become nauseated when I got to the part in The Year of Magical Thinking when Joan Didion described her late husband’s health issues:

His cardiac rhythm had been slipping with increasing frequency into atrial fibrillation. A normal sinus rhythm could be restored by cardioversion, an outpatient procedure in which he was given general anesthesia for a few minutes while his heart was electrically shocked, but a change in physical status as slight as catching a cold or taking a long plane flight could again disrupt the rhythm.

John Dunne’s last cardioversion took place in April 2003. Nine months later he’d be dead of a heart attack so sudden he couldn’t lift his arms to catch himself before falling and smashing his face into the dinner table.

These days I’m less glib about death, despite the general and sustained ugliness of so many things. Plane flights scare me more than they used to, and I drive slower, with visions of shattered glass and scorched metal easing my foot off the gas pedal. Perhaps that’s just because I’m older now, not a nineteen-year-old who can’t see past Thursday. Perhaps it’s because a lonely ambulance ride will do that to a person. I’ve always been aware that the potential for tragedy surrounds each of us constantly, but nowadays that tragedy seems just an inch closer to me than it was before. I’ve come to think about my heart the way others think about god, an all-powerful force I can’t see that could wipe me out on a whim. I will catch people looking at me on the subway, staring quizzically as I stuff my hand up my shirt to clutch my chest and see if anything’s amiss. I stand stock-still to better feel the beats. I think to myself, Best of luck.

Photo by Marcin Krzyżanowski

Save Yourself is the Awl’s farewell to 2015.

To Live and Die in L.A. (Again)

by Meghan McCarron

In the summer of 2005, I moved to Los Angeles. In the summer of 2006, I left. In the summer of 2015, I moved to Los Angeles again. I wish this were some tidy story about striving and exile and triumphant return, but it all happened by accident. I moved out here after college on a whim; I moved back because of my girlfriend’s job. Now the weird, lonely person who lived here ten years ago, who I had mostly managed to forget, is my guide at every intersection and my companion at every restaurant. We compare notes a lot. It’s strange to bury a piece of your history; it’s maybe stranger still to exhume it.

My original move to Los Angeles happened like this: Two weeks before graduation, the head of my college’s film department randomly took me aside in a hallway. She told me she could put me in touch with screenwriters hiring assistants. But I could not wait! I had to move to Los Angeles immediately.

Up until that point my post-graduation plan was to go home to Philadelphia and then maybe move to San Francisco with my friend Martha (sorry, Martha). But the impulsive, zany urgency of moving to Los Angeles now was too hard to resist, so two days after graduation, I started driving across the country. My brother came for company and we crashed on friends’ couches and smoked weed with their high school friends and ate gigantic biscuits in Flagstaff, Arizona, and we drove until we hit the ocean.

I did not get those jobs. Does it even need to be said? Qualified professionals in their late twenties got those jobs. I spent the summer living in a dining room in Westwood and reading a copy of Story from the library. One of the screenwriters offered me an internship and promised to lie to prospective employers that I was his second assistant; my graduation gift money would last me a month or two, so I accepted. The production office was a tiny room in a giant backlot, where I was trapped alone with their real assistant, who could not stand me. I drank Diet Coke to curry her favor and listened to our boss’s calls, which mostly consisted of complaining about the cost of private school with other producers. When I got a real job in the industry, my new boss did me a solid by requiring I stay an extra hour each night so that I got an hour of overtime pay even though he had little for me to do. I spent an inordinate amount of time trawling the office in search of the gigantic, luxurious cupcakes that fancier departments were sent as gifts.

In other words, I was very lucky, but it did not do much to diminish existential dread. No one is happy the year after college, especially after leaving a coddled liberal arts bubble, but I had underestimated how much better it might have been to be miserable in Brooklyn with my friends than miserable in a surreal, sunny city where I knew no one.

A few months in, I got an apartment with a friend, but she and I were on wildly different schedules. When we did overlap, I was terrified to let on that I never, ever had plans on Saturday night. Or any night. Instead, I spent an incredible amount of time driving back and forth across the city. It’s quaint to think about now, but back then, only the fanciest people had GPS. To orient myself, I obsessively drove major arterial roads: Hollywood, Sunset, Santa Monica. I don’t remember why I kept driving these routes; I just remember it seemed the only possible way to figure out where I was. Astro Burger on Santa Monica, I decided, was the perfect restaurant, and I ate hamburgers there constantly. A small treat after was a stop at an open air car wash, feeding coins into the meter and covering the car with slick green soap before blasting it off with a hose.

I did find some friends, or at least people who were willing to hang out with me. At a temp job, my fellow receptionist turned out to know my friend Martha. They had gone to elementary school together in Moscow. Another college friend invited me to shows at Spaceland and matzo ball soup at Canter’s. Activities helped, too: Building a bicycle from spare parts, joining a science fiction writing group that met at a Denny’s, coaching a youth rugby team.

Sex, of course, was a disaster. At this point, I had one foot out of the closet, but one still very firmly in. I went on desperate dates with girls I met on MySpace (this was 2005!) and made out with random dudes I met at parties. At a bar during the Super Bowl, I found myself and a friend of a friend competitively flirting with a Suicide Girl. Two comics writers got me and another girl drunk and then told us they were sadists. A group of lesbian screenwriters adopted me and invited me to their weekly bar nights. I was horribly in love with one of them who later told me, “I only date hot people.” But in retrospect, I am hopelessly grateful for those nights sitting at plush outdoor lounges near the Beverly Center or standing around gay leather bars, hardcore military porn playing on the TVs above our heads while we made small talk about agents.

Under all that misery, I liked LA. I liked blasting Annie while crawling through Koreatown during rush hour. I liked the tall, elegant palms lining the streets in my neighborhood, liked the mountains surrounding the city, liked watching old movies in palatial theaters, and liked eating hamburgers in the same place Hilary Swank went after winning an Oscar, something I knew because a picture of her in a formal dress hunched over a burger was framed on the wall.

But beyond a vague urban satisfaction, there was nothing holding me in LA, and when the opportunity came to take a new job in a new state, I left as impulsively as I arrived. Nothing was holding me anywhere, in fact, so I spent my twenties teaching at a boarding school in New Hampshire and selling books in New York and writing about restaurants in Austin. Out of all my moves, the only one I regretted was LA. I had done so many thirsty, entitled things there, and wasted so much time.

But perhaps I had just lunged toward the city too soon. When I was applying to college, my mom had a rule that I could not apply anywhere in California because I would meet someone and marry them and never come home. Somehow, I still found a girl from Orange County and years later, she kidnapped me to bring back to her homeland.

I’ve lost my obsession with hamburgers, and I no longer own a car. Instead, I am obsessed with tacos, which is embarrassingly on-trend but also true. When I move through Los Angeles alone now, usually it’s on my bicycle. Navigating the city by side streets and patchwork bike lanes, alone and vulnerable in a different kind of way.

I have no patience for sitting in traffic or finding parking, and driving on the freeway scares me, but when I do drive alone, that’s when I feel closest to the person I used to be. That long-gone past self sits inside me, or on top of me, the two of us moving through the same space in the same isolation. In those moments, I don’t want to go back and save her from her aimless driving or burger eating. Is there anything more obnoxious than an adult looming through the mists of time to say, “I went to therapy and met my beloved and also could probably finish a screenplay now and it gets better”?

Maybe, somehow, she will save me. You can’t save yourself without taking on some self-loathing, and perhaps someday we will drive around the city together, blasting music and wasting time, comfortable together at last.

Photo by Sarah Ackerman

Save Yourself is the Awl’s farewell to 2015.

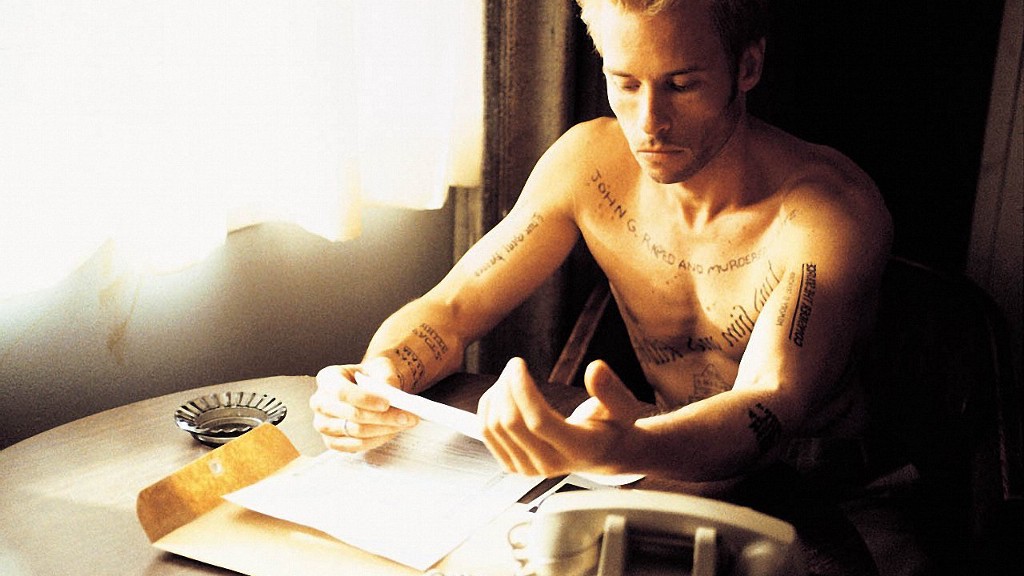

The Year Without Memory

by Sam Biddle

At the end of 2015, I realized I felt completely fucking insane. Not manic (I rarely have much more energy than the level required to write a blog or adjust Wi-Fi router settings) or delusional (keep your expectations low, rigid, and right, I say), but just fucking weird. My ability to map my thoughts and actions to the underlying reality was off-kilter, and I had no idea how to explain it. I just felt wrong. After some Googling and rare stretch of self-examination the lasted for more than five minutes, I realized at some point recently I’d lost the capacity to create and recall short-term memories.

It’s a blessing to be defective in an obvious way with simple signs and textbook fixes, but the unrelenting and pathological anxiety I’ve dealt with since my teens is murky and slippery. Treating it with a circa-2003 Shock and Awe bombardment of bunker-busting Klonopin pills in 2010, followed by a surgical deployment of quieter, agile Zoloft tablets beat it back almost entirely. I no longer had to spend hours of each day wondering if I had said something wrong in an conversation, with a vast branching tree of dialogue nightmares, stopping only when I decided that Yes, indeed, it was likely that I had said something that was interpreted in a way that would somehow hurt me in the future and anger others. I never again had a panic attack like the time in 2009 when I told a girlfriend I was en route to meet her but hadn’t even left my apartment yet, and then agonized over the possibility that someone at an adjacent construction site had seen me through the window, caught me in the lie, and informed her. I can’t believe I can even type that and it applies to me — but it’s over and that’s great, right?

The downside to mashing your worries is that everything else gets stomped on too, a phenomenon doctors I’ve googled often refer to as emotional “flattening” — the bad goes way down but good and normal feelings are also compressed. Think of it as an overly aggressive spam filter: you’re no longer getting ATTN EBAY SAM F BADDLE YOU WILL BE FIRED FOR SPILLING THAT CUP or A+++ VI@GRA CATASTROPHIC SOCIAL CONSEQUENCES, but the things you want are also suctioned away.

It’s dull and frightening to feel this way — like you’re missing most of your emotional guts — and it’s the reason I was so averse to medication until things became internally unbearable in my twenties. I’d like to think that the status quo, flat or not, is workable for the rest of my life should that be the case — I don’t feel great, but I feel good enough. So when a psychiatrist suggested I try adding Wellbutrin to my regimen for its stimulant effects, I was hesitant. I didn’t want to start taking medication to medicate against my other medications, uppers against downers, a neurological ping pong match. This was going to take my brain chemistry, speeding in one direction, and drive it directly into oncoming traffic. On the other hand, my doctor told me there was little chance the pill would make me fat. So I plunged in, and within days felt more broken than ever, having not been warned against the extreme and abrupt memory loss side effect of Wellbutrin.

I tapered off after a few weeks, and will begin 2016 not knowing whether or not I could’ve soldiered through the fog and regained a fuller emotional palette. On the other hand, I can now remember all my pleasant sandwiches and fun nights at bars and decent sunsets and good mornings and conversations with my grandfather and worthwhile articles and a lot of very, very stupid tweets.

Save Yourself is the Awl’s farewell to 2015.

Unsupported

by Betsy Morais

One Sunday evening, when the December air felt too warm, and the sidewalks were packed with storefront-gazers, I went to midtown. It wasn’t very late, but the sky had already turned black. I wore a puffy coat, which brushed against people and scaffolding with an excited “swoosh” as I walked with brisk pace to Lord & Taylor, which had sent me a freebee discount in the mail. I have never liked Lord & Taylor as much as my mother does, but their marketing department’s computer had remembered my birthday. When your birthday coincides with holiday gift-buying season, the stern sales barks — “Time is running out!” — feel all the more pressing. So off I was, in search of a bra.

I have reached that point in a woman’s life when I basically know which bra will make me feel the least lumpy and gross. Before going to this store that I don’t especially like, I checked the back of the coupon (as so many six o’clock news specials have instructed me to do) in order to confirm that the kind of bra I set out to get was not excluded from the sale. This is significant in part because I am not a person who cares deeply about designers or brands, nor am I a person who wishes to dwell at all, if I can help it, on the selection of beauty products. A bra can be beauty-enhancing thing, an assertion of one’s sexuality, or a self-pleasing extravagance, a hot frivolity, or a political statement, but it is most fundamentally, to me, an undergarment. In the morning, I am getting dressed with a wish that my bra to be the least noticeable element of the day.

I arrived at the store with my very patient boyfriend. What my boyfriend did not know was that it took many years and trials to get to the point of being able to walk into a store, and over to a particular rack, with confidence. I bought my first bra at the KMart on Route 17, in Paramus, while my mother was shopping for laundry detergent and Lean Cuisines; I wandered off, in search of some sense of autonomy. I bought my first mall bra at Victoria’s Secret, with my friend Kathleen, who assured me that this was where mature girls went. My most formative bra-buying excursion, one that many women endure, involved the kind of intrusive measuring and scooping motion and stranger touching that some experts believe is required to identify the right fit. A peroxide blonde woman wearing a mostly unbuttoned black blazer unfurled some measuring tape and went about her business in a way that she probably believed to be clinical but felt to me like a second date. In the end, though, she was the best second date I ever had, since she not only found exactly my bra size but also transformed, through a sequence of tutorials with different sample bras, the way I put one on.

Keeping those lessons in mind, I tried on a number of styles, while my boyfriend waited, taking a seat on a stool by the fitting room. From over the door, I heard a saleslady approach him, and then a muffled exchange that included the phrase “You can’t be here, SIR.” I emerged, led him out, apologized, and got some more bras to try on. Each one cost between $50 and $70. Hence the motivation of a discount. It is hard to justify paying that much for an item of clothing that exists for the very purpose of being unseen, but it is also hard not to, because without it, you certainly will be.

Here are the stakes: A bad bra can give you a bizarrely landscaped chest; it can exacerbate back pain; it can dig into your sides; it can stick out from your clothes at inopportune moments; it can itch; and it can fail to provide support (and when that is the thing you are willing to pay for and still do not receive, it is all the more disappointing).

I found a good one. It was not too padded or pointy or flashy or tight; the straps were O.K., the cups didn’t stick out, and so on and so forth, with all the considerations that upon enumeration make one feel at once both self-conscious and bored. I showed it to my boyfriend, who, more than anything, appeared relieved to be finished with this part of our day. At the register, I presented the bra, the tank top that would get me over the required seventy-five dollar threshold to receive the discount, and the coupon. The cashier was on her phone, unenthused, as if my arrival at this phase did not represent a personal victory. This is not merely a purchase, Miss; this is underwire. She rang me up and told me the total. “Sorry, the system won’t allow you to use the discount on this — ” she began. No, I protested, that can’t be. Yes, she said, pointing to her screen, it could.

Regret, the agony over squandered opportunity, is often felt acutely in December, on a birthday, when hours are devoted to dragging yourself to shop for a bra that you cannot in the end afford. Should it, could it, be easier than this? My great-grandmother, after arriving in America as a young woman, worked in a brassiere factory in New York stitching pieces together; I’ll never know whether she had any grand theories about any of that. A load of emotion and alienation and history and gender-complication is bound inside a bra, but it can’t merely float abstractly as a symbol of something else — it’s got a job to do. I admit that at times I’ll enjoy a bra, though that must be partly because my satisfaction with it has been so well earned. A woman’s bra can be her own measure of herself, and on this night I was going home empty. These and other frustrated thoughts filled the resentment-purse inside my ovaries, as my boyfriend and I descended the escalator. “Well, it wasn’t a total waste of time,” he said. “I got accused of being a pervert in a lingerie department.”

Save Yourself is the Awl’s farewell to 2015.