Allies For Everyone, "It Takes All Kinds"

Save this for late, late, late at night when you’ll need it most, and then enjoy.

Writing Russia

“Like every other culture to have held and lost the world’s attention (think France and Germany), it acquired the terrible habit of viewing every new product or event in grand terms of national decline or renaissance: Even light entertainment is a battleground for the country’s perpetually frustrated quest for global relevance. When a show or a film bombs, the public reaction is not that the writers are bad, it’s that Russia has failed yet again. If it succeeds, the reaction runs along the lines of ‘Finally, something we don’t have to be ashamed of.’ The highest form of compliment to a book, a movie, a show or a song is the word ‘nestydnyi,’ literally ‘unshameful,’ which implies that shame is a baseline condition of existence in Russia — and that the moments when that shame is alleviated are rare and precious. And that’s the secret of Putin’s genuine popularity: his talent for alchemizing this unfounded shame into equally unfounded pride by substituting territorial conquest for actual achievement.”

— Awl pal Michael Idov’s “My Accidental Career as a Russian Screenwriter” is a worthy sequel to his “My Two Days as a Russian Tabloid Sensation.”

New York City, January 5, 2016

★★★ The heater had baked a dry patch at the back of the throat overnight. Wisps of steam flared short distances from the building tops. Here and there someone had salted an icy patch on the sidewalk; spilled liquid had frozen in rivulets where it ran. The cup of coffee from the luxe bakery slipped out the sides and top of the lid and dribbled down the new glove. There had been none of the glossy brand-colored plastic lid plugs on the counter by the milk. Finally it was necessary to stoop by the curb and pour a steaming jet of coffee out into the gutter to get the sloshing under control. A man in a knit Philadelphia Eagles hat walked up the avenue with a woman in a knit New York Giants hat. The thermometer indoors on the office windowsill said it was 64 degrees indoors. The deep afternoon cold did not prevent a note of marijuana smoke from floating on the open air in Union Square. “I smell kush, man!” one young man declared to another. “I smell kush, too!” the other replied. The trains were stuffed, hot, and dysfunctional. The express train arrived on the local track and went 30 blocks nonstop from there. On the walk back from the express stop, a foot slipped on a narrow slick of black ice in the roadway.

Vox Media Terrorized by Pissroach

Earlier today, Eater’s new executive editor Helen Rosner (congrats!) referred to a “beautiful” companywide email. The Awl has acquired it from an anonymous source, and we have learned that Vox Media’s New York office manager Becky Rosefelt may be the bravest and most patient soul in media: She is currently combatting a gigantic pissroach on behalf of Vox’s many salesdudes.

Hello gentlemen of the 9th floor,

Now that 25% of you have approached me bearing an iphone 6 with a picture of a cockroach in the urinal, I’ll address this head on.

There is a cockroach in the urinal on the 9th floor.

Since I don’t want to touch it any more than you do, I’ve requested that the building take care of it. This hasn’t occurred yet, but when it does, I’m happy to notify you. No, you were not the only one to almost have a heart attack or wet yourself (although that’s the place to do it) — urine in good company.

Please refrain from showing me anymore cockroach pix. Check yourself before you insect yourself.

Thanks

Vox, a billion-dollar company, is reportedly moving from its current pissroach-infested offices in Midtown to seventy thousand square feet of space in the Financial District at 85 Broad Street, the former headquarters of Goldman Sachs. We hope, at least for the office manager’s sake, that in addition to its many other amenities, that it is pissroach-free.

UPDATE: At least some Recode employees were not informed of the pissroach.

UPDATE II: Tipster: “Greg T. Gordon — Executive Director of Video, Vox Creative — for the kill.”

UPDATE III: Original pissroach photo added.

UPDATE IV: August 29, 2017—According to Jenny G. Zhang, newsletter editor for Eater, the pissroach (or a relative pissroach) has returned, this time to haunt the women’s bathroom

pissroach has returned to vox media 🙃 https://t.co/tWW78JSfPB pic.twitter.com/SEZ4mY8GAf

— Jenny G. Zhang (@jennygzhang) August 29, 2017

And here is a video:

grainy af video for your pleasure pic.twitter.com/V5nGKCmBEd

— Jenny G. Zhang (@jennygzhang) August 29, 2017

WHY IS IT DROOLING??????

Photo by Becky Rosefelt

Better as a Tweet

A great number of journalists, including most who cover Twitter, have made the service a major part of their jobs. It functions less as a resource than a context; a feed-and-follower-based framework that matches a reporter’s self-conception better than most of the other things they do at work, where their stories are filed and piled into publications with diminishing sense of direction or purpose. It’s a place where they feel listened-to, at least by their peers; it’s a place where their news can get just the right amount of traction, becoming visible to thousands of people without totally losing context. It’s a service that allows the writer’s ego to remain, if diminished, at least intact. It is a place where reporters perform their jobs in every sense of the word.

And so of course we’re mad! This time about [CHECKS TWITTER] the long tweets. Jack Dorsey, writing in the voice of the first-ever man to discover that sentences can be linked together into groups larger than two but fewer than infinity, responded to leaked news reports about “10,000-character tweets” with this announcement:

— Jack (@jack) January 5, 2016

“We’ve spent a lot of time observing what people are doing on Twitter, and we see them taking screenshots of text and tweeting it,” Dorsey writes. “Instead,” he asks, “what if that text… was actually text?” Not-quite answering his not-quite rhetorical question, he says: “That’s more utility and power.”

Screenshotting text is a common recent behavior: celebrities posting screenshots of notes; publications posting preview quotes; most commonly, probably, readers screenshotting and highlighting the parts of links they most want their followers to read. Twitter has been gradually and deliberately adding new types of media to Twitter posts for half a decade: with clickable hashtags; with shortened links; with images, then grids of images; with “Cards,” which preview text — many characters of text! — and pictures; with videos, then auto-playing videos; with quotes of tweets inside tweets. 140 characters, once an all-encompassing limit, became just one limit of many: you can have this many photos, this many links, and these many letters tying them all together. As Matt Buchanan wrote in 2012, after the introduction of one of an endless line of “new Twitters”:

So, this is the Twitter we have today, and the one we’ll essentially have for the foreseeable future, particularly since Twitter has pushed out third-party developers and clients that would give us an alternative way to look at and use Twitter. It’s rich and graphical and dense and will only become richer, denser and more media-heavy still. It’s ultimately a different service now, no longer simply about the best you can do with 140 characters.

Then, a conclusion that could have been written at the end of basically any Twitter article published since: “Twitter may well be just as important today as it was yesterday, if not more so, but the things we’re saying with it now just don’t feel quite so essential anymore.”

Anyway, people were posting images of text on Twitter for lots of reasons. They posted images of text because there was no other way to write long. They posted images of text because they wanted to highlight a quote. They posted images of text because… they wanted to post images of text! For all its reported struggles with growth, Twitter still has the rare privilege of being a destination — a platform that people check frequently and repeatedly, from which they find other things. People are linking to images on Twitter? Let’s incorporate images! People are watching YouTube videos from Facebook? Let’s host videos of our own. People are reading articles from the feed? Let’s… put articles in the feed! Platforms are markets; they research themselves. It’s a great setup for the platforms! And one that Twitter has embraced enthusiastically, gradually assembling a service out of features conceived and tested by users and (mostly now defunct) third parties. (Down to its logo. Down to its verbs!)

So the capability to post longer text posts that expand inside the feed seems especially notable because posts can be counted in characters, and Twitter is known for its character count. But a feed in which you can already tap “play” or open a grid of photos into a slideshow or open a link into an internal browser is a feed in which tapping a text preview to see more text will feel natural. It won’t take long, I imagine, for links to start to feel almost out of place — for Twitter to feel a bit more like Instagram, where users frequently write blog-length captions, and where the links and the web effectively don’t exist.

Like each change before it, longer text posts will alter the character of Twitter — they will make certain behaviors more attractive and common and will marginalize others. Alternative link-shortening services still exist for a very narrow set of uses — analytics, mostly — and plenty of people still post links to images or gifs hosted elsewhere. But the dominant link and image behaviors on Twitter became, as soon as was possible, native.

What’s unusual about text, and which helps explain why journalists’ reactions to this change are so confident and visceral — as opposed to the resigned and uncertain responses they have to changes in Facebook, which, to them, is much more powerful in ways they can control much less — is that, unlike, say, native Twitter images, which marginalized a small number of Twitter-specific companies, longer posts change a professional calculus for anyone who uses Twitter to promote writing online. An old boss used to say, half-joking and then eventually not joking at all, “maybe that story would be better as a tweet.” What was initially almost pejorative — said to mean “short” or “slight” or “unworthy of a longer post” — became a complex judgement. Could this piece of news be conveyed well in a sentence or two with an image or video? Could we just screenshot that statement, or release, rather than asking people to follow a link to a post where it’s quoted? If the answer is yes, then the corresponding reader question — would I rather see this on Twitter, or click on some site — is answered as well.

The ability to post 10,000 characters will make the answer to that question “yes” in a majority of situations. Possibly a large majority! This post, for example, would fit in a 10,000 word text card. I doubt anyone reading it expanded in their Twitter feed would think, “damn, I wish I was reading this on a website instead of right here! I wish I had clicked a link, for some reason!” This is somewhat worrying if you’re in the business of making posts against which ads are sold.

In the past, the tweeting media professional could attempt to justify the enormous amount of labor invested in the daily use of Twitter with a number of arguments: it sends traffic, which makes money with ads; it develops loyalty not just to me, your employee, but to you, my employer; it keeps us in “the conversation,” or “a conversation,” or “the most readily visible conversation.” The first argument, which was always questionable — Twitter never sent THAT much traffic, and the arguments that it was somehow especially valuable traffic were conveniently unquantifiable — barely applies. The jokes about journalists all “working for Twitter” suddenly become true in every way except one.

Longer text will, in this way, ruin Twitter for the people who are most vocal about its ruin: it will make the work they do better for Twitter, better for Twitter users, but worse for them (or at least their employers). If Twitter could absorb what’s left of blogging, great news for Twitter! Moments seems like it might be a better, or at least more complete, product if a “collection of tweets” could include a little more text, right?

Now commence some now-familiar conversations:

— If readers never leave Twitter, what does a publication matter to them?

— If readers never leave Twitter, how do posters get paid?

— If posters get paid, why only those posters? Because they work for publishers? Didn’t we just lose track of what a publisher is?

— How would revenue sharing work? Twitter doesn’t really monetize posts or videos or images so much as it monetizes the entire feed, so… ???? (I think this explains, somewhat, some publishers’ early experiences with Facebook Instant articles, which are returning significantly lower ad rates per-reader than heavily monetized webpages. Facebook’s like “nope, that’s the right amount of ads,” because they also monetize outside of individual posts, in the feed itself; publishers are like, “hey, uhhhh, we need to be making a LOT MORE on these posts to keep doing what we’re doing??” And then everyone backs out of the room shrugging. Allegedly.)

And some newer ones:

— Why would your interview subject, who is on Twitter, talk to you for a post that you’ll be putting in a text box on Twitter?

— Inline Twitter writing would be… different, right? You wouldn’t just write a straight new article to be read inline — it would have to feel sort of natural in the flow? It’s maybe not a place for stories so much as… announcements? Announcement-like things? Stories told like announcements?

— Twitter is currently testing non-chronological feeds, and already shows you tweets you “missed,” etc. A stronger emphasis on engagement will naturally favor native posts. This isn’t a question I guess.

— Will this make arguing on Twitter easier? (Or just more tempting, oh god)

— Do tweets become… headlines for themselves?

— What’s the end-game? Where does that gradual trajectory of follower growth end up? At a sad plateau corresponding with the death of Twitter? Somewhere else entirely? Just… here, forever? Hm.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves here. The only question in Jack’s post was “What if that text was… actually text?” More utility, more power. For Twitter.

Wild Nothing, "Reichpop"

I have to think that should this song somehow fail to put you in a good mood it will, at the very least, not put you in a bad mood, which ought to count for something. You’ve started off the day much worse, probably even this week. Still, it’s almost certainly better for everyone if you let it put you in a good mood, so try to work with that. Enjoy.

New York City, January 4, 2016

★★★★ Blue dawn light came through the blinds not long after the smoke detector started chirping its battery warning. It would keep chirping, irregularly and intermittently, despite the new battery, as the full day came on and the clouds began clearing, till the maintenance men came and replaced the whole thing. In the northwest a low line of purple cloud, with pink on its top edge, stretched parallel to the purple line of the hills, with pink haze at their feet. Outside was the genuine sharp cold. The new parka went into service, with the new hoodie under it in anticipation of the office chill. The sky had become intensely, intensely cloudless. The Decker Building and its vertical ranks of filigree leaped out the row by Union Square. A swing stage carrying a work crew up a blank but irregular brick wall swayed toward and away from its shadow. The gloves had not turned up in any of the obvious coat pockets in the morning. Where were the gloves? It was certainly time for new gloves. The gloves would be one block west, one long block. Gradually the shade crept out into Fifth Avenue from the west side of the street. The gloves had not been gotten yet. The sunny fraction dwindled and was gone. Still no gloves. The walk west under the scaffold, in the bright electric light, with the wind blowing litter — it felt, for an instant, like a return to a familiar place after long absence: winter night, in this city, again. It was a briefly pleasant thought, the pleasantness made possible by the truly stalwart fabric of the parka. Then there was the store with the gloves, and another pair of jeans, and, why not, a pair of long underwear bottoms. The elastic was failing on the old ones, if memory served. Preparations had been lagging, but it was time.

What's in a Spotify Name?

by Jake Tuck

A musician’s name used to function as part of a fairly simple brand. Artists attached words to themselves that signified their coolness: “The Rolling Stones” is a cool metaphor that uses rocks; “Salt-N-Pepa” is a cool appropriation of condiments; “… And You Will Know Us by the Trail of Dead” is a cool goth sentence with a cool vestigial ellipsis. Now artist names have an additional function: they serve as metadata to be used in sorting music online. Sure, before the rise of streaming apps, some artists may have worried some about SEO (it’s not a great idea to name a band “The The” or “Yes” or “Search Engine Optimization Tips” anymore); but now that Spotify et al offers access to most of the music in the world, all in one place, there’s a more acute problem: if an artist doesn’t pick a name that no one else in the world has ever used, dumb computers are going to throw them into the same bucket as other artists.

From a Spotify user’s perspective, manifestations of this issue can be quite annoying. I recently got an alert from Spotify that Andrew Hill, the legendary jazz pianist, had a new song out. I was surprised — I didn’t think he still made music. I eagerly clicked on the song. It was a strummy breakup ballad with lots of water imagery. Andrew Hill the jazz pianist has been dead since 2007. This other Andrew Hill was squatting on his artist page.

If you can work through momentary annoyance, however, this common-name effect can be embraced as a pleasantly janky browsing function — especially if you’re interested in obscure international metal. Recently I visited the Spotify artist page for the rapper Despot, who has been working on his debut album for over a decade. There I found a full-length album, and I was very excited. Despot finally dropped his Detox! Except, no, the Despot that made the album I was listening to is a Brazilian black metal duo. Again, at first I felt duped, but then I kept listening; I wish I knew enough about South American metal that I could afford to dismiss happy accidents like this, but that’s not the case. A similar thing happened when I got an email from Spotify notifying me that Women, the great Calgary post-punk band that broke up a few years ago, had a new release out. I thought maybe it was a re-release of an old album or something. Nope, this Women is a British stoner metal band. Again, I briefly felt let-down, then got over it and wallowed in riffs for upwards of one and a half songs.

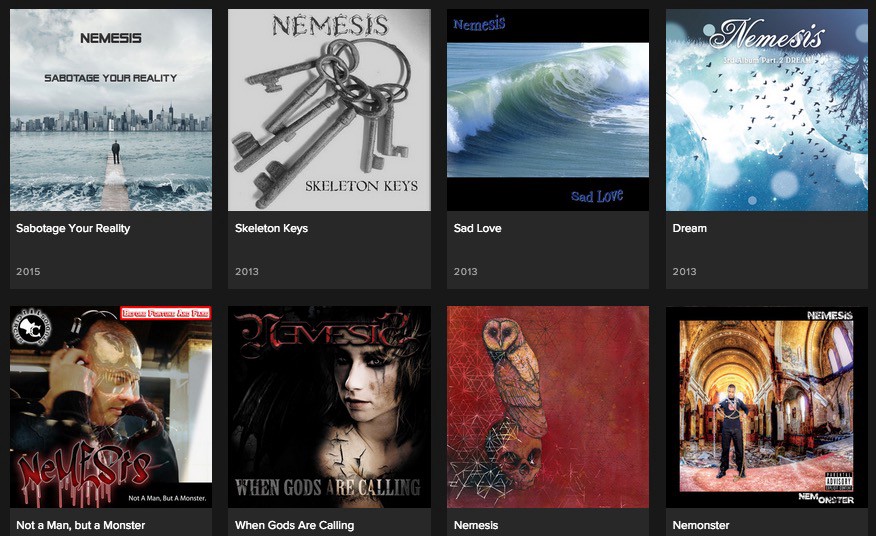

I’ve since gone deeper into the Spotify library and found some names with truly sick multivalence. I discovered “Nemesis” through this list of widely used names in metal, but there are just as many non-metal acts sharing the space. It’s possibly the apotheosis of badly-indexed online music (the Spotify artist page for “Apotheosis” is also also badly indexed, but not to the extent of “Nemesis”). There’s Nemesis the Chilean rap duo, Nemesis the Dallas rap crew, Nemesis the K-pop band that kinda sounds like Phish, Nemesis the other K-pop band that sounds less like Phish, Nemesis the German power metal band, Nemesis the Baltimore down-tempo deathcore band, Nemesis the Ohio hardcore band, Nemesis the Virginian butt rock band, Nemesis the Serbian DJ, among others.

I Facebook-chatted with the Nemesis responsible for the most recent full-length album on the page, the English electronic artist also know as Nick Snow. Though he hadn’t been on his Spotify page in years, when he checked it out, he was “a bit shocked at how disorganized it is.” When he came up with “Nemesis,” over ten years ago, after inspiration from a scene in Snatch, his Google research only turned up an old rap group, so he stuck with the moniker. “I didn’t expect so many other groups to pop up with the same name,” he said. If he had used his given name — which I half-expected to have been taken by several EDM DJs — he would’ve had an artist page all to himself.

Spotify does not seem actively interested in fixing this. The company provides a Google Docs form to submit metadata issues, and fixes them, sometimes. Not to defend an app I don’t think works particularly well, but the task of sorting all this confused metadata is a bit Sisyphean; music is constantly getting dumped into the Spotify catalogue; artists switch labels; deals with the service are made with labels or, worse, bundles of labels. Metal bands are still mining the Wikipedia page for Norse mythology. Indie bands are still fascinated by large woodland mammals and the beach. Rappers are still calling themselves Yung $omething. Guys named Andrew Hill or Chris Brown or “Joe” are failing to consider that a unique stage name might go a long way.

If you’re naming your band now and don’t want to fall into a tune-bucket, here are some recent examples to follow: Even before The Weeknd blew up and effectively subsumed anyone with a similar name (poor indexing most affects lesser-known artists), he differentiated himself from Weekend and Weekends, two other end-of-week acts I was already listening to when Abel Tesfaye appeared on my radar. He exploited the coolness of mundane words, but didn’t lump himself in with other acts doing the same thing. Similarly, the weed-punk guy Wavves — who might have ended up in the Spotify page for several bands called “The Waves,” one of which makes some very calming flute-synth muzak — has a Spotify artist page all to himself. And while you might make fun of a band called The World Is a Beautiful Place and I Am Not Afraid to Die, but they will never have to share Spotify real estate with a Maltese symphonic metal band.

I, Rodent

by Maud Newton

Last year started with fluey nightmares about mice. I dreamed of mice used in research to benefit humans: “frantic” mice, for studying anxiety; “Methuselah” mice, known for longevity; and mice with human liver cells and brain cells and tumor cells. I also dreamed of mice that, as far as I know, exist only in my mind — mice with human lungs, brains, or hearts growing out of their bodies to replace our worn-out organs.

If you’ve been on the internet for a while, you’ve probably seen that photo of a lab mouse with a human ear jutting out of its back. Controversy about genetic engineering raged after it first made the rounds in the late nineties, but researchers were quick to note that the mouse was a naturally occurring immunocompromised mouse, a “nude mouse”, and not genetically modified. (It did have cow cartilage implanted beneath the skin in the shape of an ear, though.)

Nude mice, and others like them, were used in research until scientists engineered more severely immunocompromised mice, some of which are “knockout mice” whose manufacturers inactivate selective genes based on the type of research they’re intending to do.

I was eleven and visiting a friend who was about fourteen when some of her even-older friends showed up. “If you were an animal,” one of the boys told her, “you’d be a lynx.” He was handsome, with an easy, generous smile, and he continued around around the circle. This friend was a zebra, that friend was a grizzly, the next was a fox.

Eventually he reached me, took in my pale skin, my freckled face, my enormous brown glasses. “You’d be a mouse,” he said. I wanted to turn over the coffee table and throw a lamp against the wall, quash his judgment with ten seconds of fury. Instead I smiled regretfully and nodded. I wasn’t up to a scene and objecting politely would only confirm his opinion of me.

Growing up, I was often compared to mice, usually because I was quiet, but also because I was small. I heard it to mean that I didn’t register, that I was doomed to insignificance and anonymity.

Before I started having the nightmares, I’d been reading about mice used in human research for years. Generally, I exposed myself to stories about them in the way many of us do: Transfixed but cringing, curious about the science, flummoxed by the advent of such potentially dystopian experiments, hopeful for people who might be helped by the research, sad for the mice themselves. After reading, I quickly clicked away to something less fraught.

Last December brought a wave of reports about mice infused with human brain cells. They were vastly smarter than their mouse-brained counterparts, said the researchers. Nevertheless, the researchers contended, the brains of the engineered mice were still fundamentally mouse brains, not human brains, because the parts devoted to thinking consisted entirely of mouse cells.

Though I didn’t enjoy being compared to them, I always liked mice. When I was eight or nine, my mom gave me two, one black and one white. Despite the assurances of the pet store clerk, they were not both boys. Soon I had ten mice, in different colors. I separated them, males in one wire-covered aquarium and females in the other. The males chased each other around the cage and bit each other’s genitals. This was normal, my mom assured me.

A favorite friend visited from California. We took all the mice out to play and they got loose in the room. Every last one went into hiding. I worried they’d be eaten by our cats or that they’d live in the walls and procreate endlessly. I lay awake and imagined them cowering and shitting behind bookcases. Their interchangeability troubled me; I’d given them names but sometimes got them confused. If only a few came back, would I know for sure which ones they were? I left food out and somehow within six days I’d recaptured them all.

A week or two later, reckless with triumph, I took all the mice out again. Again, they got away. This time, after I gathered them up, my mom took them to the pet store and left them. She suggested this solution, and I quickly agreed, or maybe it was the other way around. In bed at night I tried not to imagine them, their bodies trembling, hearts racing with terror, as they ran from someone’s pet snake.

According to New Scientist, the researchers put human brain cells into mice by injecting ”immature glial cells” from human fetuses into baby mice, where they ”developed into astrocytes, a star-shaped type of glial cell,” and became invasive.

“Within a year, the mouse glial cells had been completely usurped.… The 300,000 human cells each mouse received multiplied until they numbered 12 million, displacing the native cells. ‘We could see the human cells taking over the whole space,’ [said the lead researcher]. ‘It seemed like the mouse counterparts were fleeing to the margins.’”

Astrocytes, the story notes, “are vital for conscious thought.”

A year after my friend’s friend said I was a mouse, my parents had divorced and my mom had remarried. Somehow we had a new white mouse, only one this time. My stepsister’s cousin, who was about six years old, put the mouse in her shoe and then put the shoe on.

“Take it off! Take it off!” my stepsister and I screamed.

After a couple minutes, the cousin’s mother intervened. The shoe came off and the mouse came out. It lay limp in the cousin’s hand.

“It’s dead,” my mom said, lifting the tiny white body. “It suffocated to death.”

I touched its tender nose, its prickly little feet. I remember tears, but I can’t recall which of us cried, it was so awful and shocking.

Knockout mice have been around awhile, but their rat counterparts weren’t feasible until fairly recently, Nowadays there are multiple varieties.

Last year, the researchers who made mouse brains part-human were eager to try the same experiments in rats, which are considered naturally more intelligent than mice.

The team chose not to try the experiments on monkeys, however. ”’We briefly considered it but decided not to because of all the potential ethical issues,’” the lead researcher said.

Some months after the mouse suffocated in the shoe, we — my mom, stepfather, sister, stepsister, and I — moved to a house behind a shopping center with restaurant dumpsters that attracted vermin. My sister and I refer to this place as “the first rat house.”

The rats already had a stronghold when we moved in, and their fortifications grew with time. They only came out at night, and only in the kitchen, probably because it was out of reach of our dogs, who patrolled the place during the day but were sequestered with my mom and stepfather when it got late.

On the kitchen counters, in the sink, across the floor, the rats teemed and scrabbled. The room was papered in demonic red-and-white toile, its garish red cabinets and scuffed scarlet linoleum accentuating the surrealist horror movie vibe.

During the year we lived in the first rat house, my mom got two cockatiels. Within weeks she had twenty. Soon she branched out into parrots, parakeets, and finches. Eventually I realized that the rats flourished during our time in the first rat house because of the birds’ droppings and the husks of their feed.

It’s impossible to know how many many kinds of knockout and humanized rodents exist, in part because, if you’re a researcher, you can have the mice tailor-designed just for you. One company claims to provide at least seventy-five hundred strains.

On a webpage titled, “Why mouse genetics?” the company explains, “humans and mice are surprisingly similar. We share more than 95 percent of our genomes and get most of the same diseases…. A mouse with a specific disease or condition can serve as a model or stand-in for a human patient with that same disease or condition. This allows scientists to conduct experiments that would be ethically impossible in people.”

When we moved into the second rat house, it wasn’t a rat house yet. It had a pool and jacuzzi and, in several rooms, mirrored velvet seventies wallpaper. By that time my mom had accumulated more than a hundred birds. A few lived in our house; more lived in the yard; most lived on the back screened-in porch.

It must have been impossible for any self-respecting rodent to resist the bounty of spent kernels, plucked corncobs, and continually-flowing birdshit our house had to offer. By then we also had about ten dogs and after our boxer and Westie swallowed a few of the more intrepid rats whole, the rats of the second rat house, like those of the first, only came out at night and only in the kitchen.

If I needed something to eat after midnight, I liked to give them plenty of time to hide. I’d stomp to the threshold, reach quickly around the corner to turn on the light, and bang away for a bit. Then I’d return with even more noise, hoping they’d all have dispersed. Sometimes I saw them lumbering down from the sink, rushing to their mysterious tunnel under the cabinets.

In one of my favorite short stories, E.B. White’s “The Door,” a man ponders rats that a professor has “driven crazy by forcing them to deal with problems which were beyond the scope of rats, the insoluble problems” stemming from seemingly simple questions such as, which door leads to food and which leads to a shock.

Then the man catches “a glimpse of his eyes staring into his eyes, and in them was the expression he had seen in the picture of the rats — weary after convulsions and the frantic racing around, when they were willing and did not mind having anything done to them.”

I have no idea how many rats there were in the second rat house. Let’s just say, very very many. While I was away at college, my stepfather discovered that they’d eaten through concrete and established an enormous nest beneath the garbage disposal. He cemented the area back up, but even this didn’t eliminate them.

By the end of my family’s time in the house, I was in my mid-twenties and living elsewhere. Some of the rats had grown to the size of housecats. When I visited and deployed the lights-and-clattering gambit, they just leered at me from the counter.

So far, whatever discussion exists in the scientific community about how humanized mice themselves might be affected by, for example, having human brain cells, seems to focus on the ways we’ve succeeded in making the mice more like us.

Late last year, I read George Church’s Regenesis: How Synthetic Biology Will Reinvent Nature and Ourselves. As I wrote a few months afterward, the book is fascinating and repellent, brilliant and facile. It inspired my research into lab mice and my nightmares about them.

After I tweeted about humanized mice and linked to a site that sells knockout rodents, ads for genetically modified mice started following me around the internet.

I only encountered rodents in the wild — by which I mean, outside a pet store or my own home — with any regularity when I moved to Brooklyn at age twenty-eight. At night in the subways, the rats ran along the tracks, eating fallen Cheetos, licking soda straws, playing and fighting with each other.

Most things about the city are disharmonious with the timid animal part of myself I tend to disavow. There’s far too little nature and far too much noise, and it’s dirty and crowded and brash. But it’s taught me things.

I was too nice when I moved here, in a compulsive way. If someone seemed to take a dislike to me, I couldn’t stand it. Unless they were nasty enough to make my aggressive side kick in, I would keep trying to charm them, to show how genuine I was, how helpful I was, how well-intentioned. I met a woman who would later become one of my best friends, but who took a dislike to me because I wouldn’t stop doing this kind of scrambling. The harder I tried, the more chilly her responses. Much later, after we’d become close, we talked about the night we first met.

“You were like a hamster in a wheel,” she said, putting her hands up and paddling to signify running. “Squeak squeak, squeak squeak.” Nowadays she hates that she said this, but it was one of the most helpful things anyone has ever told me. After that, whenever I found myself hamster-wheeling, I knew I needed to stop. I tried to focus on my Cheetos, lick my straw.

Humanized mice give us hope of freedom from illness, from fear, from the inevitability of death. These are all things I was taught as a child that believing in Jesus could do. In the Bible story, though, the son of God chooses to become human.

Several years ago, my father-in-law died of multiple myeloma. In August, one of my best friends died of diffuse B Cell lymphoma. Both of them lived longer than they otherwise might have because of experimental chemo that was likely honed through research on knockout mice.

Former president Jimmy Carter announced last month that he’s free of tumors that were in his brain and liver earlier this year. He was given the experimental drug Keytruda, which was tested on syngeneic mouse models.

We’ve engineered rodents to take on diseases for us, to suffer so that we might be healthier and happier and live longer. Because of this, some of us have extra time on the planet. And also, because of this, lab mice exist in myriad permutations, many of them miserable.

We have brought these creatures into being. What are our responsibilities to them?

For a couple years I’ve been studying the Alexander Technique. I started because I had bad posture and a racing overanxious brain and nothing else I’d tried until then (apart from psychotherapy) had helped much with either.

The Alexander Technique is difficult to describe, but it can teach you to reduce unnecessary tension by becoming aware of your habits, of things that have come to seem inherent to an activity but aren’t really. For example, thinking doesn’t actually entail clenching your jaw or wrinkling your forehead, even if you always do those things when you’re concentrating. Sitting doesn’t need to involve swinging your arms. Texting doesn’t have to induce hunching.

Something you can do to try to train yourself out of habits like these is to tell yourself things like, “I am not sitting down,” even as you sit down, and see what happens. Or tell yourself, “thinking is not a jaw activity,” or even, “I don’t have a jaw.”

I’m describing it poorly, but the Alexander Technique has acquainted me with so many knotty places in myself that I can work with more easily now. One that remains mysterious is just below my chest, between my heart and my gut. It’s a spot that always feels kinked.

“Sometimes it helps to imagine what it feels like to be inside there,” my teacher said recently.

I’ve learned to take these suggestions seriously and when I got home later I tried feeling my way into the spot. It was hard like a walnut on the outside. The thunder of my heartbeat reverberated all around. Prying open the nut, I found a small brown mouse, trembling and uncertain, its whiskers twitching. It was braced to hamster-wheel. It expected to be disavowed. It’s okay, little mouse, I thought, and the kink loosened slightly.

This essay has been edited to reflect the distinction between humanized mice and knockout mice used in human research.

Photo by Lucas Cobb

Save Yourself is the Awl’s farewell to 2015.