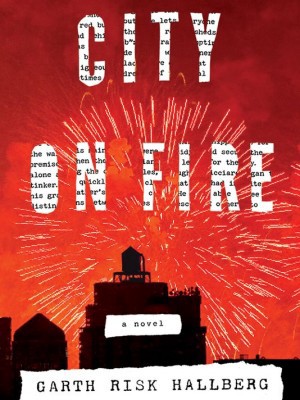

The 50 Most Unacceptable Sentences in City on Fire, In Order

by Carmen Petaccio

Like many a novel before it, City on Fire, Garth Risk Hallberg’s overlong debut that takes place during the 1977 New York City blackout, comprises a series of sentences. Here are fifty of them.

50. “Just then, a horripilating Scaramouche appeared at her elbow.”

49. “Detonations crash in from nearby like the walls she’s a void at the center of.”

48. “Every time a truck passed the frayed ends of the wine’s wicker sleeve trembled like the needles of some exquisite seismometer.”

47. “Hairs snowed crimson on the formica.”

46. “Steering between the Scylla of too-much and the Charybdis of not-enough, he’d worked hard to project a retiring asexuality.”

45. “Only out in the corridor did Charlie look back, so that the last thing he remembered seeing before forging on through the maze of the basement and up stairs was the two men, one burly and one small, inclined almost Talmudically over the sink, murmuring over what it contained.”

44. “She seemed to want to retract any extension of herself, to become a move-less white egg.”

43. “What was the thing they used to say, back when there were no skyscrapers? The higher the building, the closer…Oh, God.”

42. “Like reggae music and Amateur Night at the Apollo, soul food was one of William’s elective affinities with negritude.”

41. “But that was where the drawing ended. Below was just white space.”

40. “Goodbye, bird.”

39. “The winter sky wheeled around until he was face to safety-pinned face with Sam’s so-called friend, Solomon Grungy. Fee-fi-fo-fum.”

38. “That I may yet myself be delivered.”

37. “But of course, this was true of everybody; who didn’t exist at the convergence of a thousand thousand stories?”

36. “It was supposed to be about America, and freedom, and the kinship of time to pain, but in order to write about these things, he’d needed experience. Well, be careful what you wish for.”

35. “He could hear her upstairs now, her feet pressing faint concavities into the ceiling as she roamed from oven to fridge, humming along with the other countertop radio she hadn’t touched in years.”

34. “Bruno’s indifference to the fiscal was part of why she was able to work for him with a clean-ish conscience, but now that their fortunes were yoked together, she would have liked to have seen a little more entrepreneurial vim.”

33. “And you have to hand it to the man in the miniskirt. Even when the siren bloops, even when the megaphone sizzles to life again, s/he stands his/her ground.”

32. “It was like trying to squeeze toothpaste back into the tube.”

31. “The sun over Jersey was medium rare.”

30. “Soon patches of unaccountable hair would bloom on his blemishless body and strange yearnings would seize him like giant fists.”

29. “She couldn’t tell if it was good, exactly, but no one could say it wasn’t ambitious.”

28. “Then the detective, who must have seen the look on her face, spoke up Solomonically.”

27. “Having finally finished his article, he would deliver the fanzines to his friend Larry Pulaski. Only here came that other friend, Complication.”

26. “Mercer couldn’t see one anywhere, but like some bounding St. Bernard of the metaphysical, he couldn’t quite let go of the belief that there must be an objective reality out there, beyond his own head.”

25. “Looks like you got a real shitstorm on your hands, Pulaski.”

24. “She wanted to rub his come into her skin like a transfiguring lotion.”

23. “He made a cherubic trumpet with his mouth, sucked the Cheerio down.”

22. “But all he got now was Daddy glancing over the top of the business section, like an ornithologist at some mildly diverting bird.”

21. “Lines were forming in the lineless face, cinching it into a moue of displeasure.”

20. “Are you going to be obstreperous all night, Bruno?” Jenny asked him.

19. “There was a period just after the inevitability of ruin hove into view and just before it smashed in to the hull of your life that was the closest to pure freedom anybody ever got.”

18. “What if one eye was missing, its soft pink socket gaping like the eye of a painting that follows you around the room?”

17. “You could hear the upstairs neighbor kids running around, like shoes tumbling in a dryer.”

16. …”but the voice set tumblers falling inside her, in a keyhole that had locked other things she ought to have known.”

15. “That she didn’t think he was was why she loved him.”

14. “‘Do you know what I like best? …Just sleeping with someone. Just being next to someone while I sleep.’”

13. “Then the sky flashed white and ripped and the rain began, a real five-o’clockalypse, and when the guitar stopped, whatever cohesion or pressure held the audience together dissipated.”

12. “…his crotch bestirred itself happily when, in the invisible understory below shoulder height, she let the back of her hand rest against it.”

11.”And here was this broad soft broad in her oversized jersey, boogieing closer.”

10. “Breasts like bronzed mangoes.”

9. “Seven o’clock was some kind of citywide dog walking hour, when hordes of ostensibly autonomous individuals, still in permutations of professional attire, rushed out of their co-ops tugged by leashes taut as water-skiers’ ropes, at the other end of which, straining like hairy engines, were spaniels, shah thus, bichon frises.”

8. “There has to be a natural limit to how long anyone can spend like this, in a black aluminum suppository lodged in the asshole of the earth.”

7. “His beard was Amish-ish. The girl wore some kind of insalubrious sports uniform and carried a bag with a broken zipper.”

6. “Once he’d carried her to the bed, he lifted her nightgown and moved down between her legs and lapped at the spiced copper there until, across the quivering swell of her belly and breasts he saw the flush leap into her throat, her hands twisting the sheets by her head.”

5. “She looked like a mythological creature, a silkie or dryad, long blond hair and a low-cut dress in which her breasts, without any apparent means of support, were offered like alluring canapés.”

4. “There were her tits, perfect pale apples, their small stems hard from the basement chill.”

3. “In the moonlight through the ceiling’s trapdoor, her tits look like soft blue balloons.”

2. “You are infinite. I see you. You are not alone.”

1 . “Great rolls of toilet paper arc like ejaculate through the black sycamores.”

Lionlimb, "Domino"

Great, muffled fun that reminds you of a thousand other things but still sounds like itself. Enjoy.

It's Always Sunny in 'Philadelphia'

by Andrew Thompson

Last week, H.F. Lenfest, the owner of Philadelphia’s daily newspapers, the Inquirer and Daily News, donated the parent company of the papers and their website, philly.com, to a local philanthropic foundation. He included $20 million to support their operations. For the past decade, the papers’ turmoil has tracked with the dailies of other cities: In 2009, they filed for bankruptcy, and have undergone multiple rounds of layoffs since, most recently in November, when forty-six staff members were let go. This move relieves them of the seemingly unattainable goal of profitability. Lenfest was the last among of a series of owners, all of whom had believed either that the market would change, or that they could somehow change it; his donation seems to mark the end of that belief in Philadelphia.

The transfer of the city’s dailies to a nonprofit comes just months after another defeat for local print media. In September, the long-struggling alt-weekly Philadelphia City Paper closed. Over the last decade, somewhat in lockstep with the dailies’ degeneration, issues of City Paper had shrunk to a gaunt thirty-or-so pages, while the masthead slowly withered. After years of appearing terminal, everything ended all at once: It was bought by a competitor — the owner of Philadelphia Weekly, a shell publication of events listings — and closed in a single motion. “This was supposed to be a Music issue,” a longtime editor began an article in the final issue. A going-away party was thrown at the city’s press club, attended by hundreds of former staffers and contributors who, like myself, began their careers at the paper. By the end of the night, most of the orange honor boxes that had occupied small posts on the city streets since the nineteen eighties were collected and thrown into a warehouse.

The last issue of City Paper included a meditation on the state of the alt-weekly, executed as a brilliant conceit: a play starring two anthropomorphic issues of the paper talking over drinks at a local bar, one named CITY PAPER, the other CP. The fictional bar contained people actually interviewed by reporters, who were cast as characters in bar scene. “CITY PAPER notices a woman across the room at a table by herself, reading a novel and sipping chardonnay. It is magazine writer SUSAN ORLEAN.” The papers invite Orlean over to the table, and a bit later invite Mike Newall, a writer brought up at City Paper and now a reporter for the Philadelphia Inquirer, who “comes over with a tray of shots.”

NEWALL: It hurts, it hurts a lot. There are so many great voices on all these platforms, but are we still getting those 3,000-word take-outs on those platforms? Is there a place where people are letting it rip? A city without a weekly — it’s a sad thing.

CP: Well, it’s not like there’s not going to be an alt-weekly —

CITY PAPER, interrupting: But how the hell did this happen? Was it us? Is it alt-weeklies in general? Everything was so clear in the ’90s. Do we even make sense in 2015?

ORLEAN: Each time the technology for delivering information changes, there’s a huge change. I think back in the day advertisers were drawn to alt-weeklies because they had a younger demographic, but I’m just not sure younger people read newspapers anymore.

Only one longstanding Philadelphia print publication has experienced a largely upward trajectory in recent years. Over the past three years, Philadelphia, a glossy magazine aimed at an affluent and overwhelmingly white audience in a city that is forty-four percent black and has a poverty rate of more than twenty-five percent, has more than tripled its web traffic from six hundred thousand visitors per month to nearly two-and-a-half million, and increased its digital revenue by fifty percent. Tim Haas, the magazine’s director of digital operations, showed me a graph of Facebook engagements-per-week with Philly media: Philly.com received about twenty-six thousand, with phillymag.com close behind, at twenty-one thousand. (The next highest site received about five thousand.) In other words, the print media market, occupied by multiple dailies and weeklies, has been supplanted online by a duopoly played out between the assets of a non-profit and a glossy magazine.

Earlier this summer, I met Tom McGrath, the magazine’s editor until his recent promotion to Chief Content and Strategy Officer of its parent company, Metro Corp., in his thirty-sixth floor corner office downtown. “I think daily newspapers have looked at the rise of the internet and understandably seen a threat,” he said. “And I think if you’re a monthly magazine, you look at the internet and see a lot of opportunity. And in the first roughly hundred years of the magazine, we’ve had a once-a-month relationship with our audience, and the web now lets us have a daily relationship with our audience. From our standpoint, that’s a really good thing.” In an ad last May to find an editor to helm its business blog, BizPhilly, its thirteenth and most recent vertical, Philadelphia invited the applicant to join the city’s “dominant media brand,” a claim that once upon a time would have sounded inflated. (I should note here that I contributed to the magazine’s website in 2013.)

“I take my hat off to them,” Mike Schaeffer, the editor of Washingtonian, Washington DC’s urban glossy, told me. “In a city where the media has really taken an enormous hit, where the big wonderful leading dailies have been in terrible financial straits and have suffered from changing management, I think they’ve had this — there’s been this big empty space in the middle of the conversation and they have really smartly stepped into it.”

As a magazine, Philadelphia would be formally recognizable to residents of pretty much any city with a namesake urban glossy, from Los Angeles to St. Louis to Atlanta. Urban glossies came of age in the nineteen sixties and developed a fairly standard template — service packages, gastrophilia, power profiles and generalized urbanity — across the country during a publishing heyday that had yet to introduce general interest magazines focused on a local audience. Some of the similarities within the genre are surely teleological (which city has wealthy residents that don’t like eating out?), but the familiar urban glossy model was also developed by regional editors working in concert. “There was a little, almost a fraternity, although it included some women editors, the top city mag editors, and we would sort of trade trade-secrets and such,” Richard Babcock, who ran Chicago for eleven years, told me. “You could shamelessly rip off a colleague basically because you weren’t direct competitors; they might be on the other side of the country.”

Philadelphia has standing to the claim of the country’s first urban glossy. In 1908, the Philadelphia Trades Council, a precursor to the Chamber of Commerce, published the first issue of “The Philadelphia Magazine, A Quarterly Business Magazine.” After a few pages of ads, the new publication introduced itself: “The purpose of this Magazine is to exploit the business interests of Philadelphia; to set forth the advantages of the City as an industrial, trade and commercial centre. In its pages will appear the announcements of representative manufacturers, wholesalers, and reliable business houses.” The introduction was followed by an essay by the mayor’s statistician, and small, charming pieces of mercantile propaganda rattling off Philadelphia’s output in rugs, millinery, silk, and so on, every issue bellowing the city’s industrial dominance. For the next forty years, Philadelphia took stock of the state of trade and manufacturing, railed against the Sherman Antitrust Act, and published the notes of Chamber affairs.

It wasn’t until 1947, with the post-war era’s increase in leisure time and discretionary income, that Philadelphia began to resemble a modern magazine — prosaic reports on shoe production began to be replaced with featurettes on model homes in Gladwyne, embryonic versions of service pieces appeared on where to vacation on the newly popular airplane, and articles on the miracles of asbestos that could be appreciated by a generally optimistic middle class, developer or otherwise. Pre-war, the Chamber publication was written by executives and city officials; post-war, it was written about them. Pre-war, it was about commodity production; post-war, it was increasingly about consumption. But despite the somewhat sudden change in tone, the magazine didn’t lose its focus on business, and a condensed and updated version of the 1908 manifesto was published for a decade under the masthead beginning in the late forties: “Philadelphia Magazine is a business magazine serving ‘The Workshop of The World’ and is dedicated to the interests of those who manage the many and varied commercial and industrial enterprises in the Greater Philadelphia Area. It is devoted, in cooperation with the Chamber of Commerce, to promoting, for the Area, an over-all development of business, civic and cultural progress.”

Over time, the publication became a financial liability to the Chamber, which sold it in 1951 to Municipal Publications, an outfit owned by the newspaper owner Arthur Lipson — and which would become Metro Corp., the magazine’s present owner. Arthur functioned as the magazine’s publisher until the late fifties, at which point his son, Herb, took over as editor, and then publisher. Herb hired Alan Halpern, the editor-in-chief who steered the magazine until the nineteen eighties, and when Halpern died in 2005, Philadelphia memorialized him by writing, “He made this magazine America’s most honored regional publication and, along the way, created the city magazine genre.”

I met the eighty-six-year-old Herb Lipson in July in his office at Philadelphia, which doubles as the headquarters of Metro Corp. He wore a brown dogtooth suit, and the combination of his own diminutiveness and his circular, black horn-rimmed glasses inevitably gave him the likeness of the character from the Six Flags commercials. His desk, a gold-fabricked antique upon which sat more antiques next to a south wall lined with framed nineteenth-century hunt scenes, was littered with scraps of paper. I assumed they were drafts of his column, which appears on the first page of every issue of Philadelphia. “It’s not always focused on Philly the way it used to be,” he said of the column, typically a brand of provocative conservatism that, over the past sixty years, has targeted desegregation, plaintiffs in the Bhopal disaster, and what he deemed excessive coverage of the events in Ferguson. “It’s things that bother me. Things like political correctness and hypocrisy. I’m trying to figure what I’m going to do next month.”

“Is that what that is?” I asked about a yellow sheet torn from a legal pad.

“No, this is a letter from someone who loves my column. I haven’t read it yet.”

“Do you want to read it now?”

“’Dear Mr. Lipson, I have been threatening to put pen to paper in observance of your monthly opinion pieces for some time and now is the time’ — I haven’t read this yet, it could be horrible — ‘I look forward to your comments and must admit that I cannot remember disagreeing with any of them.’ Gotta be an insane person. ‘Maybe it’s because of our age’ — I think he was born in ’34, whoever this is — ’and our upbringing is different than it is today. Values and tradition mean something to us. The beginning of our corrupt culture occurred in the ‘sixties and some of those characters ended up in D.C. government.’” And so on.

When he finished, he reached for a manila folder buried under more notes and pulled out a printed copy of a 1968 story in the magazine. “I have here the root cause, I don’t know what the date is — ‘Pray for Barbara’s Baby,’” he said. “It talks about Barbara and her baby and how in those days it was the beginning of the Great Society and they were rewarded financially for having babies, and she was having a baby and all her friends had babies, and she was sixteen or so. And because, I would say most of our problems today are the lack of fathers — I don’t want to get into that, but that’s what gets me crazy, the hypocrisy and PC shit, that drives me crazy.”

When his father bought Philadelphia, in 1951, Herb Lipson had recently graduated from Lafayette College, and he moved to the city to work on the magazine. He was slightly less button-down than his father; ultimately, his magazine would craft the bulk of its contents from the primary colors of power, capital and sex, only two of which sat well with the Chamber. “If we ever did something a Chamber member objected to, the shit would hit the fan,” he said. “We’d hear from the Chamber, ‘you shouldn’t be doing these articles, this that and the other thing.’” Philadelphia semi-officially remained a business publication after Arthur’s company took over, subtitled “The Magazine for Executives.” In 1960, a reader wrote a letter to the editor asking, “I wonder why you refer to the Magazine as being ‘for executives.’ Does that limit your readership?” The staffer assigned to respond wrote, “We’re in agreement with your objection. Of late, the magazine has been transcending its executive audience and building up additional circulation on the professional and governmental levels. We’ve kicked around alternative slogans and toyed with substitute words like ‘leaders’ and ‘influentials’ but have not come up with any that rang the bell.”

Philadelphia still published corporate board photospreads well into the sixties, but its birth as a consumer magazine occurred with “Lurid Locust Street: A shocking report on Philadelphia’s sin center,” written in October 1961 by Gaeton Fonzi. Alternating between descriptions of Locust Street and The Way It Used To Be, Fonzi wrote in sixties magazine jazz with vignettes of rich downtowners buying champagne for high-class hookers soliciting prospective johns: “A husky redhead who had stepped from the stage after rasping through a series of old standards approached the man. ‘Waiting for someone?’ she asked. Disillusionment had begun to set in.” Afterward, the magazine began to assume a role as a white-collar version of Rolling Stone, chronicling a loosening of morals and rising of counterculture and the civil rights movement with something between fascination and worry. Fonzi became the closest thing the region’s leaders and influencers had to Hunter S. Thompson, his stories about politics and the newfangled Playboy clubs sandwiched between articles like “You Can Still Make a Million” and exposés of sly tactics of life insurance salesmen. In 1966, Fonzi wrote “The Marijuana Thing,” Philadelphia’s version of the then-nationally ubiquitous weed article and the magazine’s first acknowledgement of counterculture’s existence. He interviewed college students who got high and wrote in the language of a detached, scouting anthropologist letting parents know what their kids were up to.

“We did stuff that was outrageous. Even I was scared to death,” Lipson said, mentioning an article about group sex on the Main Line. Like Lipson’s knowingly egging columns, it often became difficult to tell if the magazine was being satirical or serious or both at once. Fonzi’s epic stories on the Warren Commission and Walter Annenberg were serious; “Ripping Off The Welfare State,” a step-by-step guide “for the gainfully unemployed who have managed to shuck the Puritan Ethic and are oblivious to the social stigma of having someone else earn your living for you,” was satire pointed in a weird direction. Others were unclear. “A Millionaire’s Guide to Christmas Shopping,” with its recommendations for where to buy cigars for your banker and which safari your nephew might like, could as soon be read as a jab at the super-rich or a useful buyers’ guide, or both.

Over the following decade, Philadelphia got enough attention that by the seventies, issues ran upwards of two hundred pages a month and continued to grow in circulation. “No other advertising medium in this region has a greater concentration of affluent and influential readers,” Lipson would later write in a letter to readers, ultimately settling on the “influencer” title. In 1971, propelled by the success of Philadelphia, Lipson purchased another chamber publication in Boston and created Boston magazine, which is also still run by Metro Corp.

Lipson and Halpern spent the seventies publishing screeds against Mayor Frank Rizzo, whose villainy reached comic-book stature, and fretting over increasingly brutal trades unions and the ever-relaxing mores of the day’s youth. Meanwhile, the service packages that have since become the cornerstones of most urban glossies began to appear: “The Best and Worst of Philly” was first published in 1974, adopted from Boston, while the first version of the Top Docs feature was introduced in 1977. Within a couple of years, service pieces — ”How to Be Single, with 10 Great Pickup Lines”; “The Ten Safest Suburbs”; “20 Great Summer Vacations” — began gracing the cover of nearly every issue.

The seventies ended with the greatest population loss in the city’s history: Suburbanization reached a peak; the good jobs finished leaving; crack arrived; and the unwinding began. But the worse it got in Philadelphia — aside from the occasional eruption of racial anxiety, like a piece published that same year, “Is Philadelphia Going Black?,” which grimly predicted the growing black population of the city over the coming decade — the better it was in Philadelphia. In 1979, the magazine published one of the first of many packages on home buying, called “The New Philadelphia: Get it While it’s Hot!,” a prospectus for and about young home buyers moving into West Philly and Center City. “What was a well-kept secret has blossomed into a renaissance,’” it said. A few years later, in 1982, it prophesied “18 Ways You Can Profit From the Coming Boom,” reporting that “builders, investors and businessmen are convinced that a vital, new Philadelphia will reposition itself as the primary metropolis of the Middle Atlantic and discard its reputation as just another secondary or tertiary city in the Northeast.”

Who were the inhabitants of this new Philadelphia? They were, according to one piece titled “The New Philadelphians,” a suited neo-Organization Man with a Burberry scarf draped on one arm and a girlfriend draped on the other, looking down at a geezer in his armchair reading the defunct Bulletin. “Something exciting is happening in Philadelphia,” the article began. “Over the last ten — and particularly the last five — years, New Philadelphians have been arriving in record numbers. These talented newcomers are the sort who view the world as a horse race and themselves as leaders of the pack.”

By this time, the magazine’s audience of upper-crust readers increasingly lived outside of the city and in the suburbs. But the steady suburbanization of the city’s white population and the magazine’s focus on that demographic created a dissonance between the name Philadelphia and its suburban, expatriated audience. In another 1982 piece, titled “Bury My Heart at the Tacony-Palmyra Bridge” (and subtitled, “You can take the lady out of Philly, but you can’t take Philly out of the lady”), Pamela Erbe, a suburban-born writer, recalls her childhood of molting her Philly-region accent — one that is as elusive to transliterate as it is to impersonate — and she reminisces on Philadelphia’s essence after her departure from a brief time living here in her twenties. Her essay is one of the clearest expressions of tension between suburbanite-cum-urbanites’ desire for deluxe amenities while maintaining a nebulous notion of urban identity I’ve ever read:

Some people used to say that what was uniquely Philadelphia was its image of itself as a loser. They said the city’s character developed out of lousy athletic teams, lousy restaurants and a lack of any culture…Nobody wants to return to the days when the only decent food in town was served at home. The boom in entertainment is nothing but a plus. And it’s great to have the Phillies, Eagles and Sixers recognized as good teams…But neither do I want Philly to become so homogenized that it’s nothing more than New York South or Washington North, and ‘Philadelphia Style’ is just recycled Soho Chic or Georgetown Panache. When I miss Philadelphia, I, like every other expatriate I’ve ever talked to, miss those things that make Philly Philly.

Erbe’s essay is something of a rough prototype of every identity story the magazine would go on to publish over the next thirty years: To affluent and aspirational whites, Philadelphia was the accent, it was the Mummers (a local Mardi Gras-on-New-Year’s parade), the Italians (for their food), the “Stores with Funny Names,” Connie Mack Stadium (now demolished). “Most of the stories [today] are the stories we created years ago,” Ron Javers, who was editor at that time, told me. He was referring specifically to the service pieces, but Philadelphia began to reiterate not just restaurant guides, and not just stories about singles, children, developer profiles and true crime, but a particular narrative of the city, one of young pioneers rediscovering the allure of urban charm. Throughout the eighties, alongside features on careers and the social scene, the magazine published a monthly one-page featurette called “The Real Philadelphia,” the words backgrounded by a silhouette of the then-dwarfed skyline. The Real Philadelphia was the city of Erbe’s memories, nostalgic for the present — corner stores, the Ben Franklin Bridge, Rittenhouse Square, and other miscellanies from the mise en scene of urban life.

Over the next two decades, the Philly explosion continued in the pages of the magazine. “Philadelphia’s High Renaissance is upon us, a flowering seeded in but far surpassing the proto-renaissaince of the ‘70s,” a food package said in January 2000. There were booms in tech, the magazine telling readers how to “GET RICH QUICK!” There was talk of “prices gone wild” in the housing market and “teens gone wild” in the suburbs. The New Philadelphians brought capital to a new kind of skyline: “Those moving into apartments are the first generation of outsiders lured by reporters of renaissance.” The magazine profiled the developers of the high-rises as the New Philadelphians began scouting Fishtown as the “Philly ‘hood that promises to be the next Northern Liberties” and the restaurateur Stephen Starr built cafeteria after luxe cafeteria to feed them all.

If one had read nothing but Philadelphia, they would be forgiven for not knowing that somewhere in all this — after the bond market crashed and the rate of incarceration grew so wildly that local prisons overflowed and the plan to GET RICH QUICK burst with the rest of the first internet bubble — that the prices gone wild in the housing market beckoned the global financial system to a state of near collapse, causing a diffuse local mayhem and whisking away the lives of large numbers of Philadelphians.

In 1975, Lipson started a weekly paper called the new paper, the magazine’s answer to the idea of an alt-weekly. It lasted only a few issues before it folded; in 1991, Javers recalled its brief life, writing, “I’ve always thought the problem with the new paper was that it was ahead of its time. It was designed to attract Center City yuppies. Trouble was, there were no yuppies in 1975, only a few handfuls of urban pioneers slowly seeking to regentrify (hate that word!) city neighborhoods that had fallen on hard times.”

Philadelphia’s sprawling web operation is something of a delayed fulfillment of the new paper’s attempts to create a media space specifically for these so-called urban pioneers of New Philadelphia — essentially the magazine minus the suburban coverage and on a non-monthly timeframe. Between the beginning of the “High Renaissance” in 2000 and when the magazine’s internet and social media strategy launched in earnest in 2013, Center City and “up-and-coming” neighborhoods from river to river were filled with the contemporary equivalent of the yuppie, the Young Person in an Ethically Produced Hoodie, providing the long-awaited audience for thirteen different verticals. Each one reads like a streaming extract of standard Philadelphia topics, distilled on their own blogs, and all of it written in the crisp, irresistible language of the internet — the dialect of “here’s why” and “X Things To Know About Subject” and so on. “What we’ve done is try to do a real mix on Facebook,” Haas, Philadelphia’s director of digital operations, told me. “We’re like half news there and half service from the other channels. Certain things, like a lot of in depth and political type reporting and that sort of stuff, doesn’t travel very well.” What does work, though, “is a lot of identity stuff, like what we call Philadelphia identity.”

Haas pointed to a few pieces, including “The 25 Most Beautiful Philly Streets” (a list of streets); a piece about the imminent renovation of the Gallery, a lower income mall in Center City that other writers on the website had been clamoring to close for some time (“One hailed as a cornerstone of a Philadelphia renaissance…” the dek began); and a piece about a cookie factory in the Northeast closing, taking with it the smell of sweet gingersnaps. “What we try to figure out is, How do we make this snappy and worth clicking on but also giving it enough context,” Haas said. “Ithink the overall strategy is trying to put out the stuff that draws the community together, and by that I mean, through this identity stuff.”

The specter of Erbe’s essay floats throughout the site–in a piece about how far Rocky would have actually run had his iconic last scene been transposed onto an actual map of the city; in a humor piece about using different Philadelphia landmarks, like the sports stadium, to house the papal pilgrims. In 2014, “Why the Philadelphia Accent Is So Fascinating” looked at recent national press about the Philadelphia accent and a Penn study of its gradual disappearance. “The findings, which only apply to white Philadelphians ‘with deep ties to the city,’ are interesting: The change in accent is happening among Philadelphians regardless of background or education level, language change is primarily driven by women, and the Philadelphia accent — once the ‘northern-most southern city’ — is shifting to be more like Northern U.S. cities.”

“Yes, Philly, we’re starting to sound more like New York and Boston,” it read, Erbe’s fear of the city’s homogenization finally realized. “I know. It’s enough to make you want to get off the pavement and run screaming through the shtreets.”

The question that loomed for more than a decade over Philadelphia media was perhaps definitively answered when Lenfest handed his dailies over to nonprofit and City Paper died. That the dailies are now a non-profit is perhaps a technicality after having operated like one for some time. They will continue to struggle while trying to cover the city, the alt-weeklies will rest in peace, and Philadelphia will chronicle the city less as a place than as an idea. “Who reads Philadelphia Magazine, and why?” an editor wrote in 2000. He offered a profile: “Power players, suburban moms and dads, hip Old City types, opera buffs, Flyers fans, fashion victims, Philadelphians in exile (a surprising chunk of our subscriber base), and anyone else who cares about our city and region. This magazine is for you. And about you.”

In my interview with McGrath, I had asked him if he felt Philadelphia had new obligations with its newfound prevalence in our daily stream of local information. “We’ve always as a publication tried to be relevant to what’s happening in the city and what’s happening in our readers’ lives, and that mandate remains exactly the same. Does it mean that now that we’re covering things daily that we’re going to cover, I don’t know, a neighborhood meeting, well, anywhere?” he said. “I think the DNA of the brand is unlikely to change.”

Photo by Pat Belanger

Beacon, "IM U"

If we somehow survive the snow there will be a new Beacon LP on the other side of it, so at least keep that in mind. Enjoy.

New York City, January 19, 2016

★★ The four-year-old’s double-layered pants were too loose in the waist and had to be replaced with Batman pajama bottoms under regular pants. It was too warm in the apartment to put on all the necessary layers without overheating. The sweater could wait till the lobby, where the frigid air was mixing in. The shelter of the subway platform was of no benefit; descending out of the sun into it was like entering a walk-in freezer. Little shreds of cloud moved startlingly fast from east to west. People’s skin looked raw or dusty in the midday brightness. The passing of a small cloud across the sun was a momentary disaster.

Dear Birthparent

by Nicholas Mancall-Bitel

Dear Expectant Parent,

We know this is a difficult time for you, having to make a very important decision in finding a responsible and loving family that can take care and raise your unborn baby. We have come to learn that sometimes doing the best thing for our loved ones is hard and it requires a lot of courage. That is why we can assure you we are ready to offer your child a home where he or she will feel loved and welcomed not only by us but by our large family of relatives and friends. We also want you to know we would like you, as the child’s family, to become part of our extended family so you can see by yourself how your child grows happy and healthy.

The “dear birthparent letter” is often the first salvo in a larger pitch known as an “adoption profile,” which prospective adoptive parents create to prove to expectant mothers they are capable of raising children. Along with the letter, adopters include heartwarming pictures of friends and family, personal bios detailing lifestyles and family values, and requisite government certifications, all constructing a distilled snapshot of the adoptive parents. Jennifer Curiale and her husband Jason, who adopted their son Justin in July, used a profile to convince a birthmother that the couple were the right parents for her child. Having already spent some six years trying to conceive and adopt, Curiale struggled with her profile. “You try to think what you would want to know if you were in that situation: you’re a married couple, your ages, what you do for a living, your educational background,” she told me. “But then you have to decide how to portray your personality or the things you like to do.”

When most people think of adoption, they imagine closed adoption, a formal procedure in which the birthmother relinquishes her child, and any legal parental claim, to the state. Beginning in 1935 with the Social Security Act, the US government increasingly regulated foster care in all forms, and over the next forty years, the state continued to take authority from birthmothers. While increased government oversight of child welfare was undeniably necessary, under closed adoption, birthmothers not only lost privacy and control, but also any chance of ever seeing their children again, a strict measure the state justified through the illusion of biological normalcy it granted the adopted family.

However, since the seventies, public opinion has shifted, forcing new regulatory norms. While closed adoption is still common for older children coming from foster care and infants legally taken from households for abuse or other mistreatment, because the system has been increasingly associated with psychologically damaging secrecy and shame, an informal alternative called open adoption is becoming more popular among willing birthmothers. Though adopters must still pass a state investigatory report in order to qualify to care for a child, a birthmother’s approval is the primary authority in open adoptions.

As open adoption has grown popular, a new private adoption industry has sprung up. These adoptions are not necessarily decided by the strength of adopters’ conviction, but more often by birthmother demand, which differs by location and medium. For nearly every regional, stylistic, ethical or tactical adoptive niche, there is an adoption service, but they can all generally be divided into three types: local, individual agents; national and international agencies; and internet-based services. Reversing the classic image of adopters perusing a lineup of orphans, adoptive parents use these services to offer themselves to the world of birthmothers with vulnerable optimism, arguing their cases in newspaper ads or digital adoption chatrooms, awaiting any response from the void.

Some adopters choose to work with local adoption authorities like social workers and lawyers. That’s what Luis Corteguera and Marta Vicente, a couple from Lawrence, Kansas, did when they adopted in 2012. The couple, who penned the letter that opens this piece, worked with a social worker based nearby in Kansas City, who provided them access to an extensive regional network, which included local lawyers who represent birthmothers and support groups for adoptive parents. But that access didn’t reach far beyond state borders, limiting the pool of possible birthmothers. Corteguera is from Puerto Rico and Vicente from Catalonia, so the couple had to find a Midwestern birthmother looking to place a child in an international household. “People told us, because of our last names, we probably didn’t fit the image a lot of people imagine,” Corteguera told me.

The couples’ dispassionate Catholicism, middle age, and Vicente’s unwillingness to give up her career to be a full-time parent all became issues of representation in their adoption profile. It took Corteguera and Vicente over two years to finally adopt; they had planned to stop trying if it took more than three. “We didn’t know if we were going to adopt or if we could keep this up, because our life was kind of on hold,” Corteguera says. “It was pretty nerve-wracking.” The social worker offered all the advice that she could, but race was ultimately a major factor in their success: Their adopted daughter, Isabel, is Mexican-American, and the birthmother picked them partly because she could pass for their biological child.

Local birthmother preferences are less of an issue with private agencies, which utilize large national and international networks to bring adopters together with mothers from afar. However, agencies introduce new hurdles like extra paperwork, certifications, references and home studies (on top of the basic legal qualifications). They also charge for their services, adding to the total financial cost of the process. Eric Gutierrez and his partner Jim adopted their son Isaac in 2001 through an agency called Open Adoption and Family Services based in the Northwest. While private agencies can be large and impersonal, they often work both online and off, providing digital reach while maintaining traditional regional contacts; they can also offer unique services unavailable at the local level, like specific support for same-sex adoptive parents, who still face a medley of discriminatory legislation.

Setting aside the pros and cons of adopting as a gay couple, Gutierrez was at an advantage, given his experience as an ad agency director. OAFS agents taught adopters to “market their parenthood” through adoption profiles. “We were creating a brand for the Jim and Eric family. We were creating a story,” Gutierrez says of the couple’s profile. “And fundamental in advertising and branding is the communication should really point to the audience, not so much to yourself. Rather than spending every paragraph and every sentence talking about us, you want to create a communication with that prospective birthparent that’s a little bit more about them.”

But expensive, heavy-handed services don’t always yield results. After working unsuccessfully with two agencies, Curiale became disenchanted and decided to seek out birthmothers over the internet instead. “I think in this day and age, the digital network aspect is crucial,” she says. “More and more pregnant women, especially younger women who are considering adoption … go to the internet. They’re going to Google ‘How to adoption’ and just see what comes up.” She adds, “Less and less, I think women walk into an agency and ask for help. They’re in their rooms and online.”

Adoption websites, in addition to offering wide exposure, are usually cheaper than agencies, though they lack any significant support services. While Curiale was interested in connecting with birthmothers over the internet, navigating the tech adoption landscape alone remained intimidating, so she sought middle ground. She finally found success after posting her profile to Adoptimist, which functions both as birthmother network and ad agency for adopters. Taking adopter marketing to the extreme, Adoptimist helps promote adoption profiles across Google and social media through ad creation and placement, though it offers no legal, matchmaking, or counseling services. The company describes itself delicately on its website as “a technology company devoted to family-building.”

Company co-founder and president Philip Acosta launched the service in 2012 as an alternative to the leading service at the time, ParentProfiles, one of a number of adoption ventures owned by Elevati, a company based in Provo, Utah. Acosta explained to me that adoptive parents build profiles similar to those on the other sites, but that Adoptimist marketers edit the content, customizing photos and blurbs “to make the page look good.” Occasionally the team vetoes content altogether — for example, if an adopter is wearing sunglasses in a photo. “That’s not going to help them make a connection at all,” Acosta adds. After profiles are tweaked, the team distills them into ads in several sizes for maximum exposure, then blasts them across the internet. While ParentProfiles drives hits to profiles through other adoption websites, like Adoption.com, BirthMother.com, CrisisPregnancy.com, and UnplannedPregnancy.com, Adoptimist primarily pushes profiles to social media and search engines: Premium offerings include Google ad banners and AdWords, promotion on the company’s Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, and Instagram pages. Down the road, Acosta has sights set on Vine and Instagram video, though he admits it’s difficult to predict how effective any platform will be for adopters.

Like a startup in beta testing, adoptive parents on Adoptimist can use analytics like pageviews or click ratios to improve their profiles. Acosta explains, “They can see how many pageviews they’ve had, from which states, how long someone stayed on the page, all of these different statistics that they can use to find out if they’ve created a compelling profile on the site.” The site even ranks families based on these numbers, allowing adopters to see how many birthmothers (registered with the website) visit their profiles. Because Adoptimist emphasizes pageviews, rather than more significant contact like ParentProfiles’ “favorites,” traffic can be difficult to interpret. Curiale says she looked at her analytics, but admits that she didn’t understand much of the feedback.

All of these services add up, creating one of several barriers that limit who can find a child through open adoption. The total cost of Curiale’s search was around $17,000, which she says is typical for a two-year process that also involves material distribution, agency fees, legal expenses, and more. Such prohibitively expensive services practically disqualify entire tax brackets from considering open adoption. So do less visible barriers. Removing government regulation has allowed entrenched social privilege — as expressed both in the services adopters can afford to utilize and the preferences of birthmothers — to replace legal qualification as the primary hurdle to adopters. When Corteguera and Vicente were indirectly guided toward their “ideal” profile through successful examples, they immediately recognized the advice for what it was: pressure to lie in order to accommodate normative expectations. “The supposed ideal adoptive parents are a white couple in their twenties, where she is a stay home mom and they’ve got a big house and maybe a dog,” Corteguera says. “This story wasn’t really our story. It was the story we would tell birthparents.”

If there is clear upside, it is that, despite all the strategy and curation, the connection between adoptive parents and birthmothers remains as deep an emotional bond as any other familial commitment, and seemingly as random. A birthmother chose the Curiales because they, like the mother’s boyfriend, enjoy Thai food. “It’s something so little and innocuous as that,” Curiale says. Though she chalks it up to luck, perhaps such idiosyncrasies play a greater role than the marketers and adoption agents like to admit. They offer a glimmer of a person, hopeful and ready to care for a child, shining through a sea of monotonous, curated profiles.

Photo by William Creswell

Landslide, "Red Forest"

“Icy Menace” would be a good name for a band but until one appears we will just content ourselves with listening to music that fits the description. Enjoy.

The Places We Go

by William Harris

The year has turned, and Turkey’s olive groves have given way to a food scene; Hangzhou’s artistic history has been upstaged by e-commerce; three hundred new restaurants have opened in Oakland; planes will soon touch down in Saint Helena; the Alps are metastasizing with mountains of development; country clubs have taken over Vietnam’s coast; St. John awaits a megamarina; luxury bungalows have sprung up in the Democratic Republic of the Congo; and a kitschy fleet of museums is set to shake up Switzerland. There’s even more, and it’s all captured in the New York Times travel section’s “52 Places to Go in 2016,” an advertisement for places, hotels, museums, restaurants, architectural firms, and the type of world the travel section wants to see cities and nature become. It’s also maybe a dystopian novel, a stylized safe travel report from the state department, a pirouette on a postcard from this year’s most thrillingly gentrified districts.

Each year, the travel section condenses into list form the somersaulting highlights of capitalist junkspace, in which the ideology of the cityscape, as the architect Rem Koolhaas put it, is tabula rasa: rife with perpetual renovation, reinvention, razing. Last year’s list was the first one I’d read, and it was, as always, strung between development and ruination. Tourists were encouraged to go to Oman, to see its silent mountains rising up out of the desert, to see its sea breaking softly in oriental splendor, to see the moon shining over its cliffs. But they had to go immediately, before 2015 vanished, because Oman was “in the throes of a hotel boom of Dubai-like proportions,” and, due in no small part to lists like this, was about to be ruined by a stream of tourists and tourist infrastructure.

Reading the list turns vacation planning into a form of frenzied panic: Are there any idyllic locales that haven’t already been trashed and carnivalized by people doing the exact same thing I intend to do? And yet there’s hope in junkspace, or more precisely: Junkspace is hope. The list’s final irony is its faith in the magic of gentrifying reinvention. A ruined city is never actually ruined. A new christening is always just around the corner, for replacing blight or nature with a Frank Gehry is a sure way to find yourself back on the list. Hangzhou, a city an hour outside Shanghai, has twice made the list: in 2011, when the first Shangri-La hotel was built, and then again, this year, when the Shangri-La franchise decided to build the city yet another.

You get the sense there’s a system of exchange at work. It’s as if all the adjectives, or even whole sentences or paragraphs, could be cut-and-paste from one place’s description to the next, or even from one year’s list to another’s. “Always blessed with natural beauty, [X] has successfully recast itself in recent years as a luxury destination.” Is it Ubud, Indonesia? Kansai, Japan? The Southern Gulf Islands near Vancouver?

A different writer pens each entry, and what ends up coming across is the impersonality of the list, how it expresses itself through a set of moneyed preferences, a happy accordance with modernity and all it’s brought us. In a subsequent feature explaining the travel section’s choices, the editors described aiming for places “we expect to be particularly compelling in the coming year; reasons might include a museum opening, a new transportation option or a historical anniversary.” And yet there’s a clearer way to frame the formula: Follow the money. The emphasis on money and makeover puts the list in thrall to current luxury taste; it showcases a consensus, among the global jet-setting riche, of exactly which kind of spatial transformation would most enjoyably shock through our cities and peripheries.

But where has the consensus arrived? I recently saw a sample of Roland Barthes’ diary in which he journals his likes and dislikes. There’s specificity and idiosyncratic qualification to Barthes’ likes: “too-cold beer,” “flat pillows,” “loosely held political convictions.” There’s attention paid to the personal charms of place: “the bend of the Adour seen from Doctor L.’s house,” “the mountains at seven in the morning leaving Salamanca,” “walking in sandals on the lanes of southwest France.” There’s provocation (“having change,” “all kinds of romantic music”), winningly inane incontestability (“colors,” “salad,” “toast,” “the piano,” “coffee”), and a playful range (“Sartre,” “Brecht,” “the Marx Brothers,” “all kinds of writing pens”). And then there’s what he dislikes: “villas” and “the afternoon,” among other things.

The 2016 travel feature’s list of preferences, by contrast, revels in abstraction, in pseudo-contradictions, in a mix of obscene wealth and anodyne current taste, and in a perversely generous wish to offend no one which naturally turns into its opposite. The travel section likes “newly paved roads,” “lonely dirt roads,” “local over commercial,” commercial over local, “authenticity,” the spread of global capital, “Noma-inspired” restaurants, “Uber,” “bike paths,” “adding more jewels to cultural crowns,” “remote stillness,” condos, private villas, “eco-conscious treehouse-inspired resorts,” “barefoot-casual resorts,” “endearing locals,” “undulating wooden structures,” “biodiversity hot spots,” “mindful living communities,” “interactive deep dives,” “English-language travel apps,” “cool alternatives,” “locally grown avocados,” “artichoke tea,” “growing asparagus,” “eternal spring weather,” “beautiful vistas,” “Ai Weiwei,” “Anish Kapoor,” “nuanced perspectives,” “famous people seeking quiet lives,” “third-wave coffeehouses,” “gentle whale sharks,” “original beachfront boutique hotels,” “tranquil, unpretentious hideaways,” “wine-minded outdoor types,” “rare plants and endangered lizards,” “private castles-turned five-star hotels,” “Korean, Chinese and Japanese restaurants, as well as pizza and burger joints,” places “abloom with developments,” “a bit of crystal encrusted luxury,” “glassy four-story playtowers,” “suspended cumulous-shaped nets studded with 800,000 crystals,” “subterranean retail spaces,” “three-year, 44 million-euro renovations,” “five-day tourist passes,” “thriving arts scenes,” “vibrant culinary cultures,” “mixed-use developments,” “extraordinary beach holidays,” Gaudí, and “bearded liberalness.” It feels ambivalent about slavery, which it calls a “complicated legacy.” It dislikes “unfriendly encounters between rebels and tourists,” the criminalization of homosexuality, places without airports, and places that seem obvious: “Who needs the French riviera?”

A Venn diagram of Barthes’ preferences and the travel section’s collective sensibility would both circle around “loosely held political convictions,” and kept firmly on the sides would be Brecht and every preference offered by the travel section, whose goal, seemingly, is to reflect weekend liberalism’s emptiest and least polarizing likes.

Reading the list is worthwhile, however, if you’re curious about what contemporary city and regional governments are thinking — why they’re skimping on social programs and littering their skylines with gherkins and sinuous curving mounds and mirrored, tin man variations on Disney Hall. Architecture is everywhere on the list. Visit Abu Dhabi to see Gehry’s Guggenheim, Zaha Hadid’s Performing Arts Center, and Norman Foster’s Zayed National Museum. Go to Malta to bask in Renzo Piano’s renovations. In Uruguay, Rafael Viñoly designed “a gateway to the rustic countryside,” bridging the city and wine country, and it’s this last detail that’s the most telling. Viñoly got his start designing social housing, but now that neoliberal regimes have cut social spending, architecture has lost its public function. The job of today’s architect is to stuff the city with icons in a global bid for symbolic visibility, and it’s the job of the New York Times travel section to stare into junkspace and froth at the mouth, so tourists will too.

Knowing the list’s inevitability, the way it always swings back around and cycles through the world, cheerleading the rise of some new glitzy ephemera, some new contribution to climate change, some further confluence between culture and luxury, rampaging across the globe on the lookout for relevance, flashing its ad-speak, its absence of self-awareness, its culmination of the travel section’s year long championing of junkspace, it’s a little sad. And yet there’s something exaggerated about taking down the New York Times travel section. The travel section’s a more or less innocuous symptom: You can’t blame it for spectacle society, or the way high-stakes financial trading transforms space, or the colonial logic of modern tourism. But — to channel art critic Hal Foster — does it have to endorse these things so loudly? Does it have to reflect these values so thoroughly, with each changing year?

Perhaps it does, for I can’t imagine the list becoming anything else. Still, over the years it’s made adjustments. For each of the past three years, the list has suggested fifty-two places to go. But it wasn’t always this way. After starting with a bang in 2008, with fifty-three places, in 2009, there were just forty-four, and in 2010 the list bottomed out, when they were only thirty-one places to go. In 2011, the rebound began: forty-one places, then forty-five in 2012, followed by forty-six in 2013.

Over the last five years the proportions of the list haven’t changed much: pristine nature on the verge of extinction; cities festooned by the culture industry; places previously off-limits due to war or authoritarian travel restrictions; an influx of ambitious luxury developments, all receive their fair share of coverage. The writing’s cynicism, too, has remained constant. From 2012: “Tensions have cooled since violence erupted at the recent Occupy Oakland protests, but the city’s revitalized night-life scene has continued to smolder.” Or from 2015: “Security fears in neighboring Kenya have inadvertently worked in Tanzania’s favor, as far as tourism goes: Its luxurious new lodges are enticing diverted visitors.”

As the number of destinations increase, the more the list becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy, tracing the outlines of a diminishing world map. In 2013, Hvar, an island off Croatia, was number fourteen; now, in 2016, Hvar has been thoroughly commercialized — Beyoncé and Jay Z took a trip — and Korcula, a nearby island offering “authentic life,” is number seventeen. We’ve reached peak destination, and each of the fifty-two places seems shadowed by its own future, the theaters of luxury and spectacle descending on it. The list’s tagline is: “It’s a big world out there, so we’ve narrowed it down for you.” How very narrow they’ve made it.

Previously: The True Nature of The 52 Places to Go in 2015

Photo by Stuart Price / Make It Kenya

Lurker Doxxed

“The solar system appears to have a new ninth planet. Today, two scientists announced evidence that a body nearly the size of Neptune — but as yet unseen — orbits the sun every 15,000 years. During the solar system’s infancy 4.5 billion years ago, they say, the giant planet was knocked out of the planet-forming region near the sun. Slowed down by gas, the planet settled into a distant elliptical orbit, where it still lurks today.”

— Also, astronomers at the California Institute of Technology “are calling it Planet Nine (and, for the past year, informally, Planet Phattie — 1990s slang for ‘cool’).” WE DON’T DESERVE ANY NEW PLANETS.

Telekinesis, "Courtesy Phone"

This song is not going to change your life but by the time it ends you will be smiling a little bit more than you were when it started, and that is reasonably all you can ask for most of the time. Enjoy.