The People's Critics

For one of his last meals as the chief restaurant critic of the New York Times, Sam Sifton ate at “the best restaurant in New York City: Per Se, in the Time Warner Center, just up the escalator from the mall, a jewel amid the zirconia.” He (re-)awarded it the Times’ highest rating, four stars, and was so moved that he savored one dish as one “might have a massage or a sunset.” And of course he did: No one would have expected any less for Thomas Keller, long considered one of America’s greatest living chefs.

That was five years ago. Earlier this month, Sifton’s replacement, Pete Wells, declared that “the perception of Per Se as one of the country’s great restaurants, which I shared after visits in the past, appear[s] out of date” and stripped the restaurant of two of its stars. Even though it had been anticipated, it’s hard to overstate the magnitude of Wells’ review in the restaurant world: It’s maybe sort of like if people still cared what music critics said about albums and the most important one of all wrote that, like, Radiohead’s new album is not that good and certainly not great but especially not perfect?

Anyways, Wells’ takedown was received with rapt and thunderous applause: It became one of this most-read reviews in his more than four years as the Times’ chief restaurant critic and sucked the sage-scented air out of almost every other conversation in the dining world, at least for a moment. And why not? People love to watch falling stars, especially when the crash is this spectacular: The greatest restaurant in New York from one of the greatest chefs in the country is in fact a smoldering garbage fire, and has been for a year, or maybe even longer.

With the vague outlines of the-emperor-has-no-toque story, it’s perhaps not entirely surprising where the narrative went next: that Wells had somehow struck a blow for the people against a stuffy, elitist, and out-of-touch dining world. The Times’ public editor, Margaret Sullivan, noted the “populist schadenfreude,” while Jordan Weissmann at Slate explicitly valorized Wells as a “populist hero” for “his fierce emphasis on value and fairness,” connecting his Per Se review to earlier takedowns of ludicrously expensive restaurants from similarly elite chefs, Masa Takayama’s Kappo Masa and Daniel Boulud’s Daniel, as if he were charting Wells’ march to the sea. Isaac Chotiner, also at Slate, pushed this line again in an interview a few days later, at one point suggesting to Wells, “You seem to take a certain pleasure in puncturing what you see as elitism or old-fashioned pretension in fine dining.” (For the record, Wells likes “old-fashioned things when they’re done really well.”)

.@pete_wells a populist hero? Well, his second favorite chocolate bar will cost you $14. You decide.

— The Wolf of NASCAR (@CitizenKBA) January 17, 2016

But this is all a relatively strange and ahistorical reading of Wells’ reviews, even if he is the most exceptional Times critic — and one of the greatest food writers — in a generation. While a good critic does far more than merely say whether a restaurant is good or bad — there’s always Yelp or Foursquare if that’s all you want and you have a deep and abiding faith in the taste of your fellow man — considering the value of a restaurant relative to its cost is core to the entire proposition of a food critic as a service journalist, especially at a large daily or weekly paper, where their chief task is to answer the question, “Is this restaurant worth your paycheck?” Wells’ review of a restaurant that exists far outside the daily realm of possibility for most New Yorkers is also far from unusual; if anything, such restaurants were more or less the primary domain of the Times’ chief critics until the arrival of Ruth Reichl in 1993, when she began “giving SoHo noodle shops 2 and 3 stars,” which, according to her predecessor Bryan Miller, “DESTROYED THE SYSTEM.”

Nor is it particularly exceptional for Times’ critics to lambaste restaurants for the rich or splurge-y over what they deliver for a price, even considering that the audience for Times reviews have expanded far beyond the power lunchers and the lords and ladies of the Upper East Side. The first paragraph of Sam Sifton’s carpet bombing of Nello, a longstanding cafeteria for the rich, immediately hones in on the price, nearly six hundred dollars for “diner food.” Frank Bruni, Sifton’s predecessor, who first awarded Per Se four stars in 2004, was perhaps as price-conscious as Wells or Sifton, if not more so. He napalmed the institution Harry Cipriani, awarding it zero stars, explicitly citing his concern for “the uninitiated New Yorker or innocent tourist who sees the Cipriani name, with its connotations of extravagant banquets and extraordinary privilege, and waltzes through the doors expecting something magnificent in return for a king’s ransom,” and will pay “$22.95 for asparagus vinaigrette — 12 medium-size spears, neither white, truffle-flecked nor even Parmesan-bedecked — and $34.95 for an appetizer of fried calamari,” as well as “$66.95 for a sirloin, $36.95 for lasagna, $18.95 for minestrone.” Bruni concluded that the service is “so confused and food so undistinguished it wouldn’t pass muster at half the cost.” Ditto Michael’s. In his review of Kobe Club, “a cynical stab at exploiting the current mania for steakhouses in Manhattan by contriving one with an especially costly conceit and more gimmicks than all of the others combined,” he rips the restaurant for, among other things, serving measly portions of pedigreed beef for hundreds of dollars. Bruni also blasted the Russian Tea Room “in the context of dinner entrees that frequently exceed $40, appetizers that infrequently fall below $18 and 30-gram servings of caviar that cost as much as $300.” He had no problem destroying chef-deities like Jean-Georges Vongerichten (multiple times!), either. And he even employed a move that Wells was praised for in his review of Daniel — watching how a restaurant treated another table that didn’t have a critic sitting at it:

I, in turn, kept watch over other tables and listened hard to acquaintances’ reports of their experiences. I am convinced that everyone at Per Se is pampered.

Even further back, in 1998, Ruth Reichl — whose noodle-shop advocacy maybe makes her a much better candidate for a populist critic? — opened her review of Box Tree with a price-oriented salvo:

THE last time The Times looked at the Box Tree it was a pretentious place serving fancy, not very good Continental food for $78 a person, prix fixe. That was six years ago. Since then there has been a lengthy strike, which ended last month in a victory for the workers. You might think that would have improved the restaurant.

No such luck. Today the Box Tree is a pretentious place serving fancy, not very good Continental food for $86 a person, prix fixe. But one thing has changed. The service used to be genial and attentive. Now it is as pretentious as the setting — when it is anything at all.

Who knew there were so many unsung populist heroes in the archives of the New York Times dining section?

The real story of the Per Se review, obviously, is that @pete_wells found a way to untie his legacy from Guy Fieri’s.

— Ben Leventhal (@benleventhal) January 12, 2016

But there is something that distinguishes Pete Wells’ run as critic, and it’s not just his deep awareness that his potential audience is both larger and different than his predecessors — a savvy on full display in his atomic obliteration of Guy Fieri’s American Kitchen & Bar or four-star crown for Sushi Nakazawa (whose chef is mildly famous for being the apprentice who cried when he made the egg sushi correctly in Jiro Dreams of Sushi). It would be hard to overstate how profoundly high-end dining has changed since Per Se opened in 2004, during a decade or so that has been largely marked by the democratization of high-end cooking: Or, in a picture, carefully grown and obsessively sourced food, radically composed and meticulously prepared, then dropped onto your cramped table with deeply uncomfortable seats by a cranky, tattooed and taciturn waiter for tens of dollars a head. What might have seemed like sorcery in 2004, “hunt[ing] down superior ingredients — turning to Elysian Fields Farm for lamb, Snake River Farms for Kobe beef — and let[ting] them express themselves as clearly as possible” through “cooking as diligence and even perfectionism” — amount to mere table stakes for any remotely hyped restaurant in gentrified Brooklyn (or Manhattan or any major city) in 2016. What was praise from Bruni in 2004 reads like a recipe for inducing nausea today, in a world where the kind of diner who would save up for a meal at Per Se probably dreams of eating a single scallop off of a bed of smoking moss and juniper branch at Fäviken:

Sybaritic to the core, Per Se is big on truffles, and it is big on foie gras, which it prepares in many ways, depending on the night. I relished it most when it was poached sous vide, in a tightly sealed plastic pouch, with Sauternes and vanilla. The vanilla was a perfect accent, used in perfect proportion.

Leaving aside the dismal execution that Wells experienced, part of Per Se’s problem, in other words, is that it is no longer elite enough even in a city host to merely the fifth-greatest restaurant in the world. (Eleven Madison Park, which Pete Wells loved, by the way, is now more inaccessible than ever, with a starting price of $295 a head for dinner.)

This is all perhaps a long overreaction to a handful of reactions to a restaurant review, even a much-discussed one, but for the fact that the high-end dining world is currently in the middle of remarkable downshift on what it means to be a “populist,” as chefs like Eleven Madison Park’s Daniel Humm are hailed as nigh revolutionary men of the people for developing chains that serve $10-$15 veggie plates and $8 chicken sandwiches, and where Sweetgreen, a salad joint backed by a $100 million in venture capital says, with little pushback, that as part of its mission of “mak[ing] healthy food accessible,” it is opening in “food deserts” like Greenwich Village and Columbia University. (And that people who can only afford traditional fast food should really just look at the Big Picture: while a $10 salad is more than a Big Mac, an angioplasty costs a hell of a lot more.”)

Then again, against the backdrop of the current moment in dining, with the emergence of Food Culture and the attendant interest of the moneyed in displaying Actually Good Taste fueling the rise of a new breed of expense-account restaurant — one where the food actually kind of matters — exemplified by the Major Food Group empire in New York, it probably does seem remarkable that a chef with an $84 signature chicken dish is willing to make something that costs just $15, even if he’s hoping to make untold amounts of money by selling it to a million people. Populist, even?

Gwenno, "Fratolish Hiang Perpeshki"

Okay, this video may or may not remind you of what happened the first time you got to play around with the graphic filters on a new imaging program, but Gwenno’s Y Dydd Olaf was one of my favorite records in 2015 and it still sounds like summer, which is not at all unwelcome on a day such as this. Enjoy.

New York City, January 24, 2016

★★★★★ The sky had emptied out into a clear blue morning. The windblown slush had hardened into crooked fingers of ice clinging to the windowpanes, refracting the scene beyond. On the luxury building’s roof deck, the drifts were up to the controls on the gas grills. The lobby was full of bundled-up children coming and going. The four-year-old reached the sidewalk and immediately began climbing and pummeling the snowbanks, all other purpose forgotten. The snowpack on the curved glass roof of the Apple Store was dripping menacingly. On Broadway the first slush was already in the gutters. The trains were running far apart. There was a smell like wood smoke, a nice familiar after-blizzard smell, but in the Times Square station. Out the train windows, underground, there was snow: a medium-sized snowstorm’s worth of accumulation had found its way through the grates onto the 23rd Street platform; here and there snow traced the cables running along the tunnels. Huge wedges of snow reared atop the cars in Brooklyn. The four-year-old resumed his attack on the banks. A man passed wearing woolens, carrying wooden cross-country skis. A crew of entrepreneurs with shovels was digging out people’s vehicles from their parking spaces. Cars already liberated threw loose slush at pedestrians, and a truck strafed the sidewalk with salt. Steam rose from an egg-and-bacon bagel sandwich as young mouths nibbled at it on the go. Every visible contour of Prospect Park was being sledded on. The children found a pair of suitable runs and began saucering down them, while grown adults claimed the next run over. Eventually the adults fractured their last plastic disc with their weight and departed, their abandoned path glinting like a luge run. The children clustered their saucers and went down in a bumping mass. They heaved snowballs at one another. More adults arrived, sliding on a flattened Amazon carton and a partial saucer scavenged from the trash, the saucer fragment gliding and turning till it the broken edge caught and stranded the rider. A snowboarder hit the little slope, indifferent to where anyone else had been or aimed to go. The sun found a sheet of cloud and dimness fell so that the troughs of the saucer-tracks became invisible. A chill settled into the fingertips inside their gloves. The children retired from sliding and focused entirely on snowballs, keeping it up most of the way back from the park. The only complaint about their wet socks came when it was time to slip the boots back on, after hot chocolate, and their heels got stuck going in.

The Range, "Florida"

There are a few different things going on here but all of them are amazing. I kind of feel like even if you’re not me (a fact for which I suggest you spend a short amount of time at some point each day thanking whatever power to which you assign agency for existence) you will want to play this one over and over again, and if you are me (a fact for which I can assure you is the cause of constant remonstrance at every point each day against any and all possible powers assigned agency for etc.) you will have already done so. Enjoy.

An Afternoon at the Death Cafe

by Brendan O’Connor

On a cold and rainy evening, a few days before Christmas, the Rev. Dr. Barbara Simpson hosted the last “Ethical Death Cafe” of the year, at the New York Society for Ethical Culture, on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. Simpson, an ordained interfaith minister, who now works in hospice, but used to work in finance, started hosting the cafes at her home, on the Upper West Side, about two years ago. Quite quickly, there wasn’t enough room to accommodate interest, and Dr. Anne Klaeysen, a Leader of the New York Society for Ethical Culture, invited her to move the cafes to the Society’s West 64th Street location. “I always liked death. I hate to say that, but I’m always interested in everything around death,” Simpson said, laughing, shortly before the most recent cafe. Not everyone is so enthusiastic, however. “It’s a forbidden topic in this country,” she said. “People back away from me when I say, ‘I work in hospice.’ I think they think they’re going to catch it or something.”

The first death cafe was hosted by Bernard Crettaz, a Swiss sociologist and ethnographer, at the Restaurant du Théâtre du Passage, in the town of Neuchâtel, in 2004. The idea was simple: to provide an open, public place for people to gather and discuss mortality, without prescription or judgement. “If your head gets clouded up with all this religious stuff, you can’t think clearly,” Simpson said. “You’re thinking about all this stuff about religion, and ‘Did they do the right thing? Am I doing the right thing?’” She added, “It’s better just to have death. Plain and simple.” According to Jon Underwood, the not-for-profit “social franchise” Impermanence, which he founded, has helped people to organize over twenty-seven hundred death cafes, in thirty-two countries, since 2011.

A little more than a half-dozen people — all women — came to the society’s last death cafe of the year. Sitting in a circle, they introduced themselves, and explained what had brought them there. One woman was a right-to-die activist; another, who, after attempting suicide, in 1974, saw heaven, only to return to earth, was there because she still could not understand why she was alive, and that perhaps a place where death was openly discussed would be where she might figure it out. Another had simply been invited in from the rain as she was walking by.

As a child, in Penkhull, Stoke-on-Trent, a very old, English village atop a hill, Simpson’s mother would take her to a nearby cemetery, where they’d clean Auntie Alice’s granite gravestone with newspaper. “I learned to read reading gravestones,” Simpson said. “Mommy and I would go, and we would walk around the cemetery, and she’d point out and say, ‘What does this say, Barbara?’ Then we’d find a gravestone with a child’s age — eight, or something like that. I was about seven at the time. It would be very exciting! They had angels on them.” Simpson laughed. “We’d sort of imagine the angels coming to life and talking to me.”

One day, when Simpson was very young, she came home from school and found that her grandfather, who lived with her family, and would help her with her spelling tests, was not sitting in his usual armchair, by the fire. “I said, ‘Mommy, Mommy, where’s Granddad?’ And she said, ‘Barbara, he’s resting. He’s upstairs resting.’ Her tone sort of told me not to ask any more questions.” The next day, he still wasn’t in his chair. “I said, ‘Mommy, Mommy, is Granddad still in bed?’ And she said, ‘Yes, yes, he has to rest.’”

Not long after, Simpson was sitting on the stairs, playing with her dolls, while her mother, and the lady next door, Mrs. Hancock, and her Auntie Ida were in the kitchen talking about hats. “These two tall men came in, and went into the lounge area, and I didn’t know then that granddad had died, but they went in to work on his body. My mother was, ‘Oh, what do you think about this hat,’” she recalled. “They loved hats. They would always wear different hats to church and everything. And then Mommy said to me, ‘Granddad died, Barbara.’ She said, ‘Go and play with your dolls.’” Simpson went back to her dolls, and her mother and her friends went back to their hats, but eventually Simpson’s curiosity got the better of her, and she snuck into the room the two tall men had gone into and come out of. There was her grandfather, lying in his coffin, wearing a satin shirt. “I said, ‘Granddad, are you okay?’ He said — I think he really did say this — he said, ‘Oh Barbara, this shirt’s too tight.’ I swear he did talk! I was only seven. I was only seven years old. Then I heard a noise behind me. My mother said, ‘Barbara, you’re not supposed to be in here by yourself. Out you go.’ Then I had to go out and sit on the stairs again.”

When it was time to say goodbye, Simpson’s mother led her and her sister, Julie, into the room where their grandfather lay. “She said, ‘You can touch his hands if you like.’ I touched his hand, and it was cold, like the rocks in the rock garden. It was so cold. My mother said, ‘It’s good luck to touch the body.’ Then I went out,” Simpson said. “I wasn’t afraid of death at all after that.”

Photo by John Unsworth on Flickr

New York City, January 21, 2016

★★★★ The first kick of wind through the lobby door was the worst. A crumpled plastic jug scraped loudly along the sidewalk amid general litter blowing east. Despite that, the cold had softened a little more, enough that it was possible to go out and get a coffee without fumbling with gloves. The longer walk for the better coffee, even. While everyone’s attention was on the shifting dramatics of potential future weather, here was full and ample and stable sun. The light penetrated the darkened windows of a stretch limo going by, showing the empty interior. On the south-facing walk, the muscles around the eyes cramped from squinting; the gaze relaxed and fell to the red-flashing shadows. The wind worked at the hat until it could get at the ears, but it took a while, and when it got there it still didn’t hurt.

All the Mayor's Horses

by Brendan O’Connor

One of the less explicable things the affably inept Bill de Blasio promised voters during his mayoral campaign was to ban the horse-drawn carriage industry in New York City — in his first week in office. “This is an utter embarrassment,” Councilman Ritchie Torres, a Bronx Democrat, said in response to draft legislation introduced in 2014. “I have so many more important priorities in my district and this is not one of them, so I can’t believe we are spending time on this.” On Sunday, in the middle of a holiday weekend, the mayor announced a deal that would resolve the city’s most absurd and acrimonious dispute of the past two years, if it’s approved by the City Council.

The deal would not ban the horse-drawn carriage industry outright, but would shrink it significantly, reducing the total number of carriage horses permitted to operate in the city to seventy-five, down from two hundred and twenty. Moreover, the horses would move from their current stables, on Manhattan’s increasingly valuable West Side, to a city-owned building in Central Park, near the 86th Street Transverse, which would be renovated to accommodate its new tenants. The Parks Department, Politico New York reports, has for decades used the building (“the shop”) as a maintenance facility.

New York City, 19 January 2016. 🐎🐎🐎 pic.twitter.com/ogqElQUw6V

— Josh Robin (@joshrobin) January 19, 2016

Initially, New Yorkers for Clean, Livable and Safe Streets (NYCLASS), the animal-rights group leading the effort to ban the industry, came out against the proposal. “The legislation doesn’t go far enough to protect the horses from working in extreme temperatures, and doesn’t protect horses from working into old age of twenty-six,” the group said in a statement on Wednesday. “We will settle for nothing less for the horses.” On Thursday, after reviewing the agreement further, NYCLASS appeared to change course. “After careful consideration of the legislation, we support its passage to help protect the carriage horses from traffic and cruelty,” the group said. “The Mayor and the Speaker have stood up for horses and we are ready to stand with them.” Back in 2007, though, when he was still a councilman, the New York Post reports that de Blasio passed on the opportunity to stand up for horses when similar legislation came through the City Council.

Campaign finance records show that, in 2010 and 2011, de Blasio received $5,500 from Steve Nislick, who is the co-founder and president of NYCLASS. (Reached by phone on Thursday, a receptionist at Nislick’s office asked me to wait while she checked to see if he was in his office. Without covering the receiver or putting me on hold, she could be heard asking if he would take a call from “Brendan Connor, from the Awe. A-W-E.” She told me he was not in his office.) Wendy Neu, who owns the Hugo Neu Corporation (of which Nislick is the chief financial officer) and sits on NYCLASS’ board of directors, gave de Blasio $9,900. These are paltry sums, however, compared to the $225,000 NYCLASS gave to another group, “New York Is Not For Sale,” whose sole purpose was to oppose the candidacy of Speaker Christine Quinn — long thought to have been destined to succeed her mentor, Michael Bloomberg, as mayor. To that end, records show that the group, which reported over a million dollars in contributions, spent $856,762. Also, Steve Nislick and Wendy Neu sat on its steering committee.

“Those carriages are rolling torture wagons…” –@AlecBaldwin RT if U want to #FreeTheHorses! #SpeakOutForHorses pic.twitter.com/3aPJa5Y5ov

— nyclass (@nyclass) January 21, 2016

The contributions didn’t stop once de Blaz got elected, though. According to the New York Times, “Campaign for One New York,” a nonprofit organization created and run by operatives from the de Blasio campaign to help the mayor to push his agenda through the City Council, has received nearly $2.3 million in payments — including $1.1 million from real estate interests, like Two Trees Management Company, which gave it $100,000 after reaching a deal with the city to redevelop Williamsburg’s Domino Sugar Factory. Back when he was public advocate, De Blasio offered testimony before the New York State Office of the Attorney General at a hearing on political disclosure regulations for nonprofits, lamenting the rising influence of “shadowy nonprofit organizations” that he described as “not only a threat to our democracy but also to the integrity of our nonprofit sector.” Campaign for One New York has received more than $100,000 from Stephen Nislick and Wendy Neu.

“I cannot think of anything more horrible in the name of romance.” RT if U agree w/ @davenavarro! #SpeakOutForHorses pic.twitter.com/vGh1pmNeKL

— nyclass (@nyclass) January 21, 2016

Before he joined the Hugo Neu Corporation, a recycling company, as chief financial officer, in 2014, Nislick spent nearly forty years working at Edison Properties, a real estate development company owned by his cousin Jerry Gottesman. According to Politico New York, when Nislick started working for Edison Properties, in 1973, the family owned thirty parking lots. By the time Nislick retired, as CEO, in 2012, Edison owned more than two hundred lots and garages nationwide and had expanded its Manhattan Mini Storage brand across the country. Today, Edison owns twenty-one parking lots and seventeen storage locations in New York City.

As it happens, parking lots and garages are an exceptionally valuable asset in the Manhattan real estate market. A 2012 parking rate survey conducted by Colliers International found that the median monthly parking rates in Midtown and Downtown Manhattan were the highest in North America — $562 and $533, respectively. That is to say, rather than just letting a lot sit vacant until turning it into a luxury condo, residential developers can offset the cost of future construction by getting into the parking lot game. Or, having made money from the parking lot game, a developer might then get into residential, as Edison Properties did in 2007, when it began converting part of the parking lot at its 188 Ludlow Street location into a twenty-three-story, two-hundred-and-ten-thousand-square-foot, two-hundred-and-forty-three-unit mixed-use rental building. “2006 marks Edison’s 50th anniversary,” the company’s president, Gary DeBode, said in a statement. “Entering into residential development in this dynamic location is the perfect way to celebrate this milestone.” The celebrations continued as recently as this past fall, with Edison gobbling up properties throughout Hell’s Kitchen and the Far West Side.

Many in the carriage industry have suggested that Nislick may be more motivated by these business concerns than his affinity for animals: The current stables are all located in and around the area that Mayor Michael Bloomberg described, in a 2007 speech discussing plans to extend the 7 train to the still-developing Hudson Yards, as “the next Gold Coast of this city.” In the early days of de Blasio’s mayorality, Bob Knakal, the chairman of brokerage Massey Knakal Realty Services, told Bloomberg Business, “The highest and best use of this real estate is not as horse stables…The development rights are worth a heck of a lot more than the buildings currently there.” One carriage driver, Cornelius Byrne, who owns Central Park Carriage Stables and has become a prominent spokesperson for the industry, bought his stable in 1979 for less than $100,000. It’s currently valued at upwards of $8 million.

NYCLASS has denied that property values have anything to do with its efforts to ban carriages, specifically denying the influence of Nislick’s ties to the real estate industry. “Mr. Nislick will not bid on any property if it is put for sale, nor will anyone connected with this effort,” the group has said. “If the real estate were offered for free, we wouldn’t take it. Our sole interest is in the health and safety of the horses.”

Driver Cornelius Byrne says the entire fracas is about real estate, like everything else in NYC now. pic.twitter.com/SvZZpG9GGh

— Mara Gay (@MaraGay) January 19, 2016

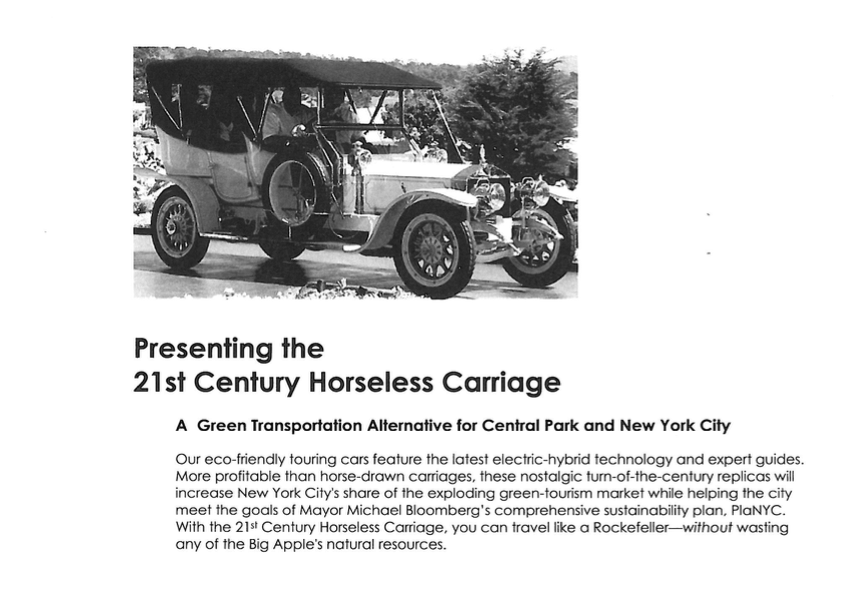

But, in 2009, a pro-carriage industry activist leaked a document, attributed to Nislick, promoting the “21st Century Horseless Carriage” — electric cars made to look like twenties-era vehicles — to journalist Michael Gross. The document, presumably addressed to those who would institute the proposal (that is, councilmembers and lobbyists), touts the environmental benefits of replacing the carriage industry with the electric cars.

However, the brochure, which Gross shared with me, also alludes to the untapped value of underutilized property: “Replacing horse-drawn carriages with the green 21st Century Horseless Carriage will create a windfall for the carriage industry from the sale of its multimillion-dollar stables alone. Currently, the stables consist of 64,000 square feet of valuable real estate on lots that could accommodate up to 150,000 square feet of development. These lots could be sold for new development, which would result in estimated incremental city-tax revenues of nearly $2 million.”

In 2012, Nislick was secretly recorded by a carriage-industry advocate, discussing campaign contributions. “It’s the best investment,” Nislick said. “Even if it’s a morally corrupt investment, you know what, you’ve got to do it, I think.” At the time, the New York Post reported, NYCLASS was pushing a bill, sponsored by Councilwoman Melissa Mark-Viverito (who is now speaker), that would have replaced the carriages with the ersatz electric cars. “In a certain sense,” Nislick reportedly said, “you’re better off euthanizing them than making them suffer that way.”

The next year, in January, Nislick — who, by that point, had retired as CEO from Edison Properties, but remained a consultant — met with then-Public Advocate de Blasio. They were joined by Nislick’s cousin, Jerry Gottesman, who remained Edison’s chairman. The meeting, Crain’s New York reported, focused not on the carriage industry, but on Edison’s interest in extending the 7 train to Secaucus, New Jersey, where Edison owns a major parking facility near the sprawling New Jersey Transit train station. Three months later, New York City Is Not for Sale ramped up its (ultimately successful) efforts to take down Speaker Quinn.

In addition to downsizing and consolidating the carriage industry, the de Blasio deal announced this weekend would also eventually confine the horses to operating inside Central Park. What’s more, it would also ban pedicab drivers from operating in the park below 86th Street. The carriage drivers are unionized; pedicab drivers are not. The union representing the carriage drivers, Teamsters Joint Local 16, supports the deal; the pedicab drivers, who are mostly independent contractors, do not. “This would crush us,” Laramie Flick, head of the Pedicab Drivers’ Association, told Politico New York. “We’re already dealing with Uber in Midtown, which has destroyed a majority of the tourist business there. This removes us from the areas that tourists want to see. It forces us into an area where the hills are really vicious, so it’s essentially a ban.” He added, “We are direct competition for the horse carriages and this is a government-enforced monopoly for the horse carriages.”

“Obviously, we’re introducing a new element into the Central Park with the horses and I think it’s a good choice, that’s where they belong, but we have to make adjustment in terms of the pedicabs for balance,” the mayor said on Monday. “I think it’s a fair outcome.”

The mayor hasn’t yet confirmed the cost of the planned renovation at the city-owned 86th Street Shops building, but the Times reported that it is estimated to be about $25 million. “It is like building a palace for a concessionaire,” Betsy Barlow Rogers, a founder of the nonprofit Central Park Conservancy, which manages the park, said. Reportedly, the mayor did not consult with either the conservancy or the Parks Commissioner on the carriage compromise. At a hearing on the proposed bill on Friday, an official from the mayor’s office reassured the city council that carriage drivers who lose their jobs will have “the opportunity to take advantage of the city’s displaced worker opportunities.” Maybe they could take up driving a pedicab.

Photo by Bob B. Brown

Francis, "Turning A Hand"

If you like sadness, or wistfulness, or the ethereal sorrow that speaks to the ache of being human, keep an eye out for Francis’ Marathon, which will be available the first week of February. Enjoy.

New York City, January 20, 2016

★★★ People were still armored against the cold, but it had lost its ferocity. A chunky crystalline icefall reached from a leaking hydrant spout to the ground, where a sheet of ice entombed a discarded page of newspaper. Gradually blue in the sky faded out. The pretzel vendor outside the school shifted his weight a little from foot to foot. The sky darkened, though it was hard to tell whether to blue or to gray.

A Poem by Taije Silverman

by Mark Bibbins, Editor

Variorum

All the pretty girls.

Parsley, sage, salt, glue.

And you’re a big help to him

says my husband’s father

when I share his news of promotion.

Hey, hey, buckle my shoe,

No sing me a new song mama

says my son before bed.

All the pretty girls.

No a new song.

Lost my partner what’ll I do,

lost my partner what’ll I do.

Skip to my lou my darling.

No another song.

Hey little girl is your daddy home

did he go and leave you all alone

I got a bad desire.

Where am I going with this

I’m thinking while he watches

his pillow to picture the words.

All the pretty girls.

He fucked the shit out of her explained

my father about the plot of a movie he’d seen.

The pretty girls.

Do you have to say that to me?

Mama another one. Mama a new one.

Well I’m sorry but that’s what he did.

You’re a big help to him.

All the pretty girls.

Taije Silverman’s first book, Houses Are Fields, was published by LSU Press in 2009. Her poems and translations from the Italian appear in Poetry, Ploughshares, The Nation, The Best American Poetry 2016, and elsewhere. She has received a Fulbright Scholarship and an Emory University Poetry Fellowship, and currently teaches poetry and translation at the University of Pennsylvania.

You will find more poems here. You may contact the editor at poems@theawl.com.