New York City, February 15, 2016

★★★★ A few coarse snowflakes drifted around in no particular order or direction, then went away. New drips were dripping on the Times Square platform. Downtown the nearly blank sky had darkened by some increment and sparse flakes were falling again. A coiling orange trickle, dried or frozen or freeze-dried to the sidewalk, marked someone’s minor disaster outside a juice restaurant. Steam veiled a truck-and-a-quarter’s worth of two Con Edison trucks standing by an open hole in the street. What was falling was almost too fine to be seen, but the roofs of black vehicles began frosting over. Then it thickened to a recognizable snowfall, one that didn’t need to be hunted against dark backgrounds. The ledge outside the window whitened so gradually that only the shine of the bigger flakes on it betrayed that it wasn’t still concrete. A white van drove down Fifth Avenue with wiper arcs cut through its white windshield. The snow had gone fully picturesque. Gradually it began taking possession of the roadway. The flakes were wet and the air had lost its arctic tightness; the space where the parka half-covered the mouth was unpleasantly humid. Outside Trump Tower the snow was unshoveled, the steps blocked with caution tape. The light reflecting off the sky was lilac. The falling snow had turned back to something unseeable and not far from rain.

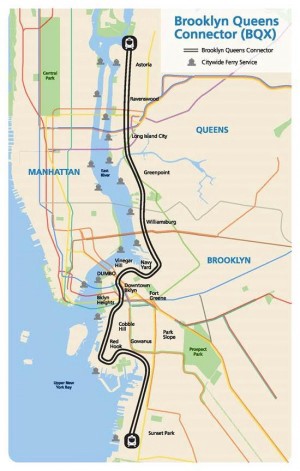

Streetcar to Nowhere

A key point of the sixteen-mile Brooklyn-Queens Connector streetcar line proposed by New York City Mayor Bill De Blasio is that it would “generate over $25 billion of economic impact” and bring “quality transit” for “all those people and jobs” in thirteen neighborhoods along the waterfront from Sunset Park to Astoria.

The mayor has stressed that, despite the need for better transit options in more marginalized neighborhoods deeper in Brooklyn and Queens, and the touch-too-emphatic support from private concerns which stand to profit immensely from the $2.5 billion project, it would not solely benefit the people who can afford to live along the luxuriously developed waterfront now and over the next few short, glorious decades left before much of the city is underwater. In particular, De Blasio and his administration have pointed to the forty thousand tenants of New York City Housing Authority developments who would, streetcar supporters say, be served by the line — roughly ten percent of the total number of people who live by the waterfront — implying an easier commute for those people to get to work or to get groceries or to do any of the other things that are harder to do when one lives in a relative transit desert. Sounds great!

3. Project will NOT provide connections to L, J/Z, N/Q (in Astoria), or F (Smith/9th)

— Yonah Freemark (@yfreemark) February 16, 2016

But, while De Blasio is promising that the streetcar line will “connect” to ten ferry landings, fifteen subway routes, and thirty-odd bus lines, it’s unclear how well it will integrate with the existing MTA system; it will, at a minimum, require a separate fare card that is merely promised to cost the same per ride. (What precisely happens with respect to any possible integration between the streetcar and the subways or buses, like free transfers, is up to the MTA, which is controlled by the state, which is to say Andrew Cuomo, who hates Bill De Blasio and anything he does to try to end run him, like having the city build its own streetcar network outside of the purview of the MTA.) The streetcar will also apparently not connect riders to at least four vital subway lines. This will make it harder for riders to commute into Manhattan, where there are still very many jobs, even if it isn’t home to the city’s favored new “innovation clusters,” like the Navy Yard, which has seen hundreds of millions dollars in new residential and commercial development, including a $380 million site anchored by WeWork, despite being essentially cut off from public transit. Oh, and if the streetcar doesn’t fully integrate with existing subway and bus transit, it stands to reason that it would also make it difficult for people in other parts of Brooklyn to reach this corridor, shutting them out from “where the present and the future of our city are happening,” to cop several lines from the mayor’s latest press release. But who knows? It’s entirely uncertain.

What is for certain though, is that the streetcar, which will serve fifty thousand people per day, will make it easier for residents of Williamsburg to reach Andrew Tarlow restaurants located in other, more distant Brooklyn neighborhoods; for people paying thousands of dollars per month to live in the tallest buildings in Brooklyn to reach the more picturesque waterfront views of Red Hook; for Brooklyn Heights families to check out the food court in Industry City; for Time workers to get to the office from Long Island City; and of course for residents of streetcar supporter Two Trees Management’s properties clustered in and around DUMBO to easily get to the rest of theme park Brooklyn with ease.

This is good enough for the Times, which seems quite taken with this project, having written around a half-dozen pieces since its announcement:

Perhaps the streetcar line would not be in perfect economic equilibrium, but it would make it possible for more people to live along the waterfront. Mass transit works like irrigation for skyscrapers and housing.

This is more or less De Blasio’s pitch for building it: The streetcar would be free because it would generate $4 billion in increased property taxes, both from new construction and increased property values spurred by the line, easily covering the $2.5 billion cost of building it. (And… maybe that’s not incorrect.)

But one might still come back to the basic question of who, by and large, will benefit from being able to live and work in whatever is built cozily snuggled up against the waterfront and the streetcar line — both amenities desired by the tasteful and the wealthy, the primary customer for luxury condos, which are the predominant form of new residential construction in this city. Of course, there’s always the hundreds of people whose applications for the affordable housing that real estate developers bake into their luxury developments for tax credits get plucked from the pile of thousands. It’ll probably be good for them, too.

Lionlimb, "Just Because"

Still very much enjoying the Lionlimb album we mentioned last month. Responses to “Domino” noted the strong influence of Elliott Smith, a comparison the correctness of which I cannot accurately assess since — and what I’m about to say here may shock and alarm you, so please be seated if you are not already — I never really got into Elliott Smith. I know this is probably very bad, particularly given my age, demographic, and low level of love for life, but I didn’t get around to it at the time and now it feels like the effort wouldn’t be worth it, what with the lateness of the hour. Sorry. If he sounds like Lionlimb, great, I can just listen to them and not need to carve out a whole new slice of my brain for another back catalog. Anyway, this music is the perfect accompaniment to a dark spring afternoon, which is what we’ve got going on here in New York right now. Enjoy.

Where Jesus Lives

by Chris Arnade

The Black Belt is a string of counties weaving through the South, in particular the centers of Alabama and Mississippi. It was originally named by Booker T. Washington for its dark soil, which was used for growing cotton on plantations where enslaved blacks had toiled. In more recent decades, the name has become associated with the high percentage of African-Americans living there. Today, the surrounding area is one of the poorest in the U.S., physically dominated by a poverty exposed and isolated: Trailers abutting county roads, shotgun shacks in small towns, and low-income ranch-style houses in the bigger towns. It is also one of the most religious regions in the country; scattered amongst the homes are churches, which, other than Wednesday nights and Sunday mornings, are quiet and still, devoid of any presence but the divine.

Andalusia, Alabama

Near Cleveland, Alabama

Near Cleveland, Alabama

Fitler, Mississippi

Jackson, Mississippi

Jackson, Mississippi

Lowndesboro, Alabama

Lowndesboro, Alabama

Montgomery, Alabama

Montgomery, Alabama

Montgomery, Alabama

Morton, Mississippi

Morton, Mississippi

Near Newton, Mississippi

Near Petrey, Alabama

Near Rolling Fork, Mississippi

Selma, Alabama

Selma, Alabama

Selma, Alabama

Verona, Mississippi

White Hall, Alabama

Correction: This piece originally misspelled two cities: They are Morton and Fitler, Mississippi, not Mortan and Filter, Mississippi.

People Recount the Times They Finally Spoke Freely

by Awl Sponsors

Sponsored by Rebtel.

Most of us goes through life politely adhering to the social norms and conventions that make everyday living easier. And that’s okay. But every now and then it’s productive to stop giving a fuck and and just say what’s really on your mind. Inspired by Rebtel’s latest ad, in which they call bullshit on the “vague, meaningless” corporate montages that dominate advertising campaigns, we asked folks to share stories about the times they — to borrow a phrase from The Real World — stopped being polite, and started getting real.

“This weekend at a wedding B. and I were shooting, the wedding coordinator walked in in a dress that was completely open down the middle so B. rushed up to her and said “oh my god, your dress is completely open!” And then the planner said “it’s supposed to be like that.” Awkward.” — Lauren, Austin, TX

“One night I was hanging out at a comedy club and got to talking to the girlfriend of my favorite comedian. I told her how awesome I thought he was and that he was the best in the business. She encouraged me to tell him how I felt. “He’ll love it!” she said. “It’ll mean the world to him.” Putting my reticence aside, I nervously –and somewhat tipsily– approached him. I told him how much his work meant to me and that he was “funnier than George Carlin.” He listened for a moment, then violently shook his head. “No way, man,” he said. “I got nothing new, man. I got nothing new.” Then he promptly walked away. Fast forward to me lying in bed that night, where I stared at the ceiling for a solid hour. Now he ignores me whenever he sees me.” — Stephen, Brooklyn, NY

And some are empowering as fuck.

“I had a boss get drunk in his car at lunch and sexually harass me. I’d told him that if he ever ‘accidentally’ fell against me again, I’d accidentally break his nose. He backed off completely, and I thought the issue was over … I saw him harassing one of our temp employees. It’s made me much more vocal in future jobs — especially on behalf of people who don’t feel they have the job security to speak up.” — F, Brooklyn

(h/t The Billfold).

“I started dating this girl who was a soccer player — she gave me a yeast infection. I was down and out and went to a doctor, I thought I had AIDS, I didn’t know what the hell I had. I was just freaking out — I had lesions all over my genital area, so one day I just said “Fuck it, I gotta talk about this.” I got shitfaced and went onstage [at a comedy club] and just talked about it. And it was going well and it was actually hitting and getting laughs, and it was amazing. I felt great, I was like “This might be what I wanna do.” … after that I was hooked.” — Mark, NYC

h/t Splitsider

I was also reminded of the time the editors of one of our sister sites published publicly a list of everyone they had ever blocked on twitter and why. In their words:

“This is a list of the forsaken and forgotten: People who tweeted too much…who posted a “Thank god it’s Friday” joke on two consecutive Mondays, who were wrong in such a way that would obviously never be remedied and therefore earns them permanent silence. If you grant that actively using Twitter and maintaining mental hygiene are not mutually exclusive, this is the proper way to do it.” — John H., NY

Some responses were just regretful that they hadn’t done this more often.

“I wish I did this more.” — A.S., Brooklyn, NY

Is there a moral here? If so, it’s probably this: life is too short to spend it just doing or saying what you think you should. So buck convention occasionally and say exactly what you want. And also maybe use Rebel Calling if you need to make international calls because it’s cheap as hell.

Denise Matthews, 1959-2016

“Denise Matthews, a pop singer, model and actress known as Vanity who toured with Prince in the 1980s before eschewing her wild persona for a life as a minister, died on Monday in Fremont, Calif. She was 57.”

Fancy Veggie Burgers I Have Eaten in Restaurants in Recent Months, Ranked

7. Salvation Burger

6. Fritzl’s Lunchbox

5. Mile End’s Falafel Burger

4. H & F

3. No. 7 Veggie

2. The Nomad

1. Superiority Burger

Photo by USDA

New York City, February 14, 2016

★★★★ The morning was a number on a screen, a number too low to seem real. The number below it was fictitious and unnecessary. Near the end of the entry rug sat the heavy boots, rumpled and waiting. The sky was weak blue and all but empty. Outside — outside! — the parka hood crackled by the ears. The cold had edited the landscape: a whole cross street was devoid of pedestrians; the Broadway booksellers and their visible wares were gone, leaving only lumpy tarp-battened tables; the bins outside the supermarket were stripped bare of fruit and flowers. Nothing remained but dried fruits and nuts, and firewood, real and artificial.

New York City, February 11, 2016

★★★ The blinds opened on royal blue sky, on its way to daylight well before the 7 a.m. airport car was due. The younger boy dragged his comforter off the bunk and wrapped himself in it on the couch, complaining of the chill. Out in full morning, a loose tangle of cloud came blowing over the roofline of a building so fast it seemed like a steam plume. It was cold but not cold enough for desperation. Here and there people walked with parcels or bags swinging from their wrists, hands jammed in pockets. The wind played its tunes on the apartment building. At night, the air in the heater cabinet, above the controls, was frigid.

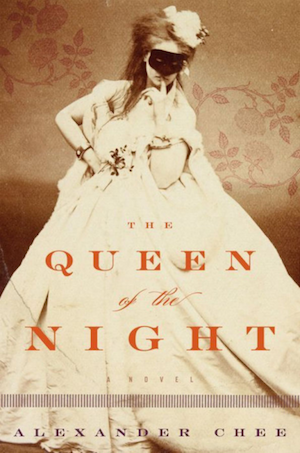

An Interview with Alexander Chee

by Jane Hu

Almost fifteen years after his remarkable debut novel Edinburgh, Alexander Chee is back with The Queen of the Night, a sprawling and operatic narrative following the life of famed soprano Lilliet Berne. Chee’s second novel, which he describes as an “alternate history novel,” is set in 1882 Paris and reimagines Second Empire Paris in startling detail. I interviewed Chee, who is currently on tour for the novel, over the last couple of weeks. If you’re lucky, you can catch him at your local bookstore.

Alex! There are lots of intelligent things I want to ask you about The Queen of the Night, but first can we take a moment to admire its spine?

Thank you to Anton Bogomazov of @Politics_Prose for making Queen his Indie Next selection. https://t.co/WErPe9ZJPu pic.twitter.com/l4T1t640iD

— Alexander Chee (@alexanderchee) January 7, 2016

Please let’s do.

It’s been almost fifteen years since the debut of your astonishing novel Edinburgh. The pace of researching and writing must be very different from what you’re going through now in anticipation of the release of your second novel. How do you feel? Are you getting enough sleep?

Thank you. I feel ok. I’m not getting enough sleep though. It’s like internet PTSD mixed with “every day is or isn’t Christmas.” Or it was. But now I’m so far past the place I thought I would get to, I feel like I can sleep maybe. I’ll check back in.

Several days go by.

Ok I’m still not really sleeping.

One week later.

I slept. It was exciting. I need more.

Also, you teach! Was as there interplay between the process of writing The Queen of the Night and teaching?

At first teaching was more or less a straightforward way of making a living and having access to institutional resources while writing — aka libraries. And that was not inconsiderable. But it didn’t in any way touch the writing. Maybe it would push the writing aside sometimes but mostly it was fine.

And then I taught at two of my alma maters — Iowa and Wesleyan — and that is a stereoscopic narrative. You see yourself as the student you must have been, with new insights as you are now a professor. So I re-experienced both major and minor interactions from my time as a student at both places as I was writing this.

How would you define a historical novel? Is The Queen of the Night a historical novel?

I think of it as an alternate-history novel — it invents a plausible interior to the collapse of the Second Empire alongside a fable. It was not, strictly speaking, a realist enterprise. I set out to make a nineteenth-century tall tale autobiography that tells the story of someone unsure if they are or are not the victim of an enchantment. But it is a picaresque also — I wanted it to be, at one level, just a big, ripping yarn.

Said another way, I had always wanted a novel-length version of Anne Sexton’s “The Letting Down of the Hair.” Having said that, I think the historical novels I admire most argue with history and the culture. And this was a way of doing that also. So by that definition, yes. It is a historical novel.

One of things I’m most interested in when it comes to The Novel is the idea of character as well as protagonicity. Lilliet Berne is ostensibly very much your novel’s heroine — its main character — but she also goes through so many permutations and disguises that it does something interesting to the idea of character as such. In ways, this seems really cool and queer to me! How did you track Lilliet through all her many iterations, while always giving her some semblance of a core identity. Or is that even how you conceptualized it?

I love that. Thank you. I don’t know that I conceptualized this quality, per se, as much as the idea of her being this way arrived as it was — I didn’t decide it as much as she did.

But this also was never very strange to me. Around the time I started the novel I sent someone a disc of photos for me for an essay we were illustrating online (that sentence should date it to about 1999), and he wrote back to say, “All of these are you?” But that doesn’t mean there weren’t challenges.

The novel began out of questions I would ask of her and the answers that came. It felt more like interviewing a presence, questions for a ghost, than an invention. But then once the writing began I wrote about three different starts for the novel, scrapping two, until with the third start I realized that all of them were the novel together. It was as if each of the sections of her life — her past in America, her life with the Majeures Plaisirs, the escape into the convent orphanage and her service at the Tuileries — each required me to believe entirely that the others hadn’t happened, much I suppose the way she would at each time.

The core of her is her incredible will to survive and escape even from God. An inner ruthlessness that is about her will to be in control of her own destiny, which is really an argument she is having with the world about the structure of the world — and the place that structure insists on for her.

The novel is all about character fate and destiny, not to mention all the wordplay between Lilliet’s Fach (a singer’s range — and a term I didn’t even know about until your novel!) and her fate. In opera, a singer’s Fach determines what characters she gets to play, but because of the narrative conventions in opera, Fach also often determines a singer’s/character’s ending. Lilliet is constantly worried that the roles she performs, as dictated by her Fach, will start influencing her fate in life. It’s a persistent concern in the novel that I sometimes forget that, well, it’s a novel. All of it is fiction. How did it feel writing about a character who is basically always trying to escape the fate she’s already in: that of being a character?

It was uncanny.

But at this distance Fach to me resembles what I think of as early aughts/late nineties thinking around identity and art that has come back to us now in new ways. As a young writer, I questioned the idea that I had to write fiction in a world where I could write my own ethnicity only and nothing else. Fach to me was a little like that. As a biracial person, that’s an inherently unstable identity.

American publishing for a long time has treated POC writers as the equivalent of minor regionalists, reporting from their immigrant experiences, as if we’re not fully a part of the world. So you can see that the idea of a voice that determines your fate forever within the dramas you’ll perform on stage — that you must only be the minor character and not the heroine with this voice, only the abandoned one with that — was fascinating to me. This however is something of a backward glance realization, as I said. At the time, I was thinking mostly of the way friends of mine raged, particularly women friends, about things like men who wouldn’t date women more successful than them, or how friends would undermine themselves professionally so as not to be threatening to their husbands. I was watching as women I knew were forced to make impossible choices even now in our supposedly enlightened time. And I was curious about that.

The Queen of the Night is available now. You can buy it wherever capitalism allows you to obtain books:

• Amazon

• iBooks

• Powell’s

The Queen of the Night is kind of structured as a series of flashbacks, which makes its plotting and temporality really interesting. What’s more, Lilliet has all these metafictional moments where she signals to the reader something she’s about to reveal, a story she’s about to start telling or one she will explain later. How does this change the reading process?

I thought of those moments as steering, really, like when you put your oar in the water to change direction.

I don’t know how it affects the reading for readers, but I know what I wanted: A retrospective novel that is a sort of memoir for her in which she is also trying to understand herself — the kind of celebrity memoir we almost never see. Most celebrity memoirs, then and now, are really just book-length PR and always were, and so there is a way in which this does take aim at that form even as it betrays it by including her actual confidences.

One of the best, that inspired this approach, was the incredible Sarah Bernhardt’s autobiography, My Double Life. Also George Sand’s Story of My Life, and her diaries, and Liane de Pougy’s My Blue Notebooks. One reviewer accused me in an otherwise positive review of inserting historical asides about various personages to make it reader-friendly, but I was after the way these famous women would do a kind of nineteenth century humblebrag: telling you about the famous people they knew was a way to tell you they were important.

The whole thing did feel like steering a massive ship, but I also wanted the individual dramatic moments of recollection to feel full of some lightness and immediacy. These interventions are meant to arrive as a way to explain what might otherwise feel like a long dramatic scene without a point. To say “here we are, here is where we’re going.”

And so part of those metafictional moments are her providing a fabulistic touch. More like Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber, than, say, Villette.

I love the detail that Lilliet is American — one detail you changed from her historical prototype, the mid-nineteenth-century Swedish opera star Jenny Lind. The novel doesn’t quite start and end in America, due to its semi-Russian doll narrative structure, but Lilliet does. She’s born there and she leaves for Europe when she joins a travelling circus and, as it turns out, finally returns there at the end of her opera career with P. T. Barnum’s circus. Since I love that kind of denigrated genre of the American Broadway musical, I really like that one of the implications here is that there are resonances between the low and the high, the circus and the opera.

It’s an idea of her character that goes back to that mistake I made while listening to that story of Jenny Lind. Her name — the Swedish Nightingale — that just seemed like the sort of name an American would dream up for herself. I was sure she had that kind of swag, and when she didn’t, I knew I had a character that was all my own.

As for the mix of the high and low, one of the earliest influences on my thinking on this novel was my friend, the Broadway producer David Binder, something of a high-culture/low-culture master himself. He introduced me to a book back in 2003 called Highbrow Lowbrow: The Emergence of Cultural Hierarchy in America, by Lawrence Levine. I did not set out to think of the novel as a deliberate mix of these things — I just knew it felt right — but once I had come up with the mix, this book, my conversations with David, these helped me see how to work with these elements. High-low is a rich mix. It was certainly the key to understanding both Barnum and the Parisian demimonde.

You go through lovingly meticulous ends to detail and describe Lilliet’s costumes and gowns. In fact, the novel basically opens with a scene about a couture dress. Throughout the novel too we learn how clothing and, in particular, women’s clothing becomes a crucial tool in political and even world historical events. I love that lingering and obsessing over gowns becomes a potential distraction for both reader and characters in The Queen of the Night — and the assumption that they might just be frivolous descriptive “filler” actually makes them more effective. But at the same time: these gowns. I want to wear them all and you describe them so gorgeously. Aaaah, say more! Did you have a favorite outfit?

In my research I became very aware of how much everyone was paying attention to what everyone else was wearing. The Empress watching her ladies in waiting who watched her; the Empress copying her husband’s mistresses (except one), perhaps as a way of getting his attention, or of telling him she knew; the need for the Empress to wear an ermine cloak but her need to sometimes just wear her flannels underneath. It was when I understood that the cloak indicated an Imperial audience that I understood that whoever took out the cloak knew her state schedule — whether they knew it or not.

The Empress Eugénie’s attention to clothes was also her way of promoting French industry. There’s a famous anecdote of when Marie Antoinette gave up silk for muslin and decimated the silk industry by setting a no-silk trend. Eugénie copied her a great deal but not like that. Fortunes for a country could rise or fall on these issues. These are not frivolous choices, even when they are.

As for a favorite outfit? I love Lilliet’s best friend Euphrosyne’s dresses maybe the most — in particular her gown when she appears at the door to her house as she leaves, and Lilliet is watching her in the dark.

Are you a very architectural, spatial, or visual writer? I’m a little obsessed with the novel’s various forms, and one is its attention to interiors. There are so many rooms in the novel, and hidden rooms, secret rooms, carriage “rooms,” prison rooms, rooms within rooms, boxes within rooms. What was your conceptualization of all of these spaces?

I took a learning test once that told me I was a visual mathematician, so you may be onto something. But rooms in this novel are specifically about class and gender as they were for the French then — this room for women, this for the servant, this for the lover, and so on. Things were so codified then that of course you would take an apartment just for an affair. Or, build a secret room for it. Or both.

For myself, I thought of the novel as something of a Merlin’s castle — -the magical castle where for those inside, each window or door opens out on another view. And now you know what a fantasy nerd I am. But that was the idea — a vast place that opened up onto many places. That was my idea of Lilliet’s mind.

You write in the acknowledgments that The Queen of the Night — a nearly six-hundred-page semi-historical novel — was inspired by a conversation you had with the late David Rakoff. The first time I met you was actually in a room where Rakoff, among other writers, was speaking, so the idea that we later became friends (full disclosure!), leading to this conversation just feels like another coincidence in the context of a novel full of coincidences. The Queen of the Night is a sprawling novel and so in ways it’s difficult to summarize, but its coincidences also allow it to come full circle in a way that’s actually formally very exact and precise. I guess I have no good way of ending this interview, so I’ll just ask: was the novel hard to conclude? How did you manage to give Lilliet an ending without necessarily foreclosing her fate?

The coincidences are engines of the uncanny. I was trying to write about that feeling we get when they happen — the feeling of a message, a “this is meant to be” feeling. She’s following their call or running from them — the story is about someone who is vulnerable to them, you could even say, even when she defied what she thinks they mean. But it was hard for me to trust this in the doing of it and the structure in the end was something I had thought of and rejected as too corny. But that was actually the point — what was it like to have something as corny as an opera plot take over your existence?

I worked with fate as I worked with history — working to discover what could be amid what was “decreed” or set down as the record. Fate and history have a similar feeling. They are weird mirrors to each other. That was why I liked working with them. It was incredibly hard to bring to an end. That I somehow saw her to her freedom, well, that feels like the result of a kiln process — something emerging from a fire you can’t watch and you hope for what it could be. And then you pull it out and it’s better than what you hoped. That was at least how it felt to me.