Alex Cameron, "Take Care of Business"

What do you think when you hear “Lynchian”?

“After the 4th of July,” my grandmother used to say, “summer is over.” So bear that in mind over the next few days, because you will be having fun on Saturday and then you will turn your head and suddenly you’ll be back at work, suddenly it will be winter again, suddenly they’ll be lowering you into the ground It goes quick.

Hey, have you guys heard of Alex Cameron? Me neither, but he’s from Prison Island and his forthcoming album is called Jumping The Shark, and if you are someone who enjoys Nick Cave, I’m Your Man-era Leonard Cohen, maybe Warren Zevon, you are going to think it’s phenomenal, trust me. It hits almost all of my spots. In fact, lemme put his other video from the record here.

The press stuff leans heavy on the adjective “Lynchian,” which is probably overused to the extent that now when you hear anything compared to David Lynch the first thing your brain does is a mental “jerking off” motion, but in the sense that it connotes the darkness and weirdness that is always present in the everyday I suppose it is appropriate in this case. Jumping The Shark comes out in late August, which is basically seconds from now. I’m telling you, it goes quick. Enjoy.

New York City, June 29, 2016

★★★★ White shirts and sneakers flared in the hard, direct sun. The humidity felt as if it had already saturated everything and was now seeping back out in all directions. The clouds were blurry but individual; gradually their edges sharpened and the day grew clearer. By rush hour they were silver and white, the clouds from the sky on some particular jigsaw puzzle assembled on the dining-room table decades ago. The dampness was gone, the temperature mild. There was no more school and there was light after dinner, so the children played tag in the slowly gathering dusk on the lawn—the lawn being the engineered grassy slope on the roof of the expensive restaurant on the edge of Lincoln Center. Two hawks met, with sharp cries, at the near corner of the top of the Juilliard dormitory tower. One flew a short distance and settled on a railing on another rooftop; the other went in long loops high in the now cloudless sky, slowly crossing the west and north and then hurtling southward with a sudden burst of speed, never flapping its wings. The eye lost it and found it again. Any fieldmarks were lost in the blood-red sunset light on its plumage. Below it, much nearer, danced the tiny dark specks of gnats.

'Performance Art' as Pejorative

Why do we use the term to deride social and political moments we don’t understand?

A couple of weeks ago, a friend posted on Facebook: “Plot twist: Donald Trump is a performance art piece created and operated by Hillary Clinton in order to deliver her directly into the sweet, sweet embrace of the White House.” Though it was a somewhat witty statement about the presidential race, I found myself rolling my eyes at yet another recourse to performance art as a method to explain the ridiculous and inexplicable persona of Donald Trump. When did ‘performance art’ become a point of pejorative comparison?

The point seems to be: he is ridiculous. Or, is it that performance art is ridiculous? Both performance art and Donald Trump are so unfalteringly ludicrous that we clearly have no other way to understand them other than to deride and ridicule their apparent absurdity. Of course, Hillary Clinton is a cool albeit somewhat kitsch piece of politically relevant installation art at the Venice Biennale, but the metaphor for Donald Trump is a naked, solipsistic, blood-smeared performance art piece taking place in your mate’s garage with two lonely audience members. Like Trump, performance art takes itself too seriously. It is ridiculous and over-indulgent, so we must make it a joke in order to subsume or placate this horrific otherness.

Performance art is as historically and culturally bound as sculpture, painting and film. There isn’t room in this article to cover the extensive, fascinating and important history of performance art (if someone wants to pay me to cover this in a sleek coffee table book, you know where to find me!), but here’s a gloss: performance art has its roots in the 1960s and ’70s as a specific turn away from institutionalized parameters. Many critics, curators and historians see the roots of performance as stemming from Viennese Actionism movements in Germany and Europe, while others track its origins to Dada, Surrealism and even the Greeks; the medium’s heritage is complex and manifold.

By comparing performance art and Donald Trump, we also toss performance art aside like an imperfect pebble at the beach; it’s a cultural, medium-specific scapegoat. We put a lot of pressure on performance art to read a certain way — as ridiculous and absurd (and often ensure it is culturally coded as unreadable). Yet, when performance art does read as unreadable, we hate it. From Kanye West’s Twitter outbursts to the below-average performances of football players, why then has performance art become a Trojan Horse for the inexplicable in society?

While it has become a catchall phrase, ‘performance art’ is also a pejorative metaphor — we use it to describe nefarious and inexplicable social, political and historical moments. Arguably, performance art has often wanted to remain somewhat obscure to the general public, so as not to become a commodity in the hands of the object-desperate art world. However, this has also ensured that performance art is seemingly beyond the understanding of your average member of the general populace. According to Tate curator Fiontán Moran, “If you think of the wonderful (I think) but cringe-worthy performance art segment in She’s All That, there seems to be a misunderstanding of performance as something indulgent, pretentious — akin to bad theatre.”

It’s a fine line, however; performance art is often seen as hammy and overblown. In an article for the New Statesman titled, “What if Donald Trump was actually an elaborate piece of British performance art?” Eleanor Margolis takes the premise that Trump’s presidential bid is ‘fake’ and by proxy, performance art is rendered as a bogus form. Performance art is a guise that hides the true nefarious meaning of something else — it is all pretend and we don’t need to be worried about the actual, real backbone: “either the ‘US presidential hopeful’ is Tilda Swinton in a very convincing skin suit, or we’re all doomed.” Is it simply easier to turn Trump’s completely unexpected popularity into performance art because by doing so, we don’t have to understand that this nauseating turn of events is real?

Similarly to Donald Trump, performance art is often seen as a joke that most people aren’t in on. But not “getting” performance art is what makes it a joke. Dominic Johnson, a senior lecturer at Queen Mary University in London, performance critic and artist, said that “some performance artists do ask for pejorative laughter, on account of not being scared of looking silly, non-serious or eccentric.” Trump asks for laughter (we need only to think of Trump lambasting Hillary Clinton for a ‘disgusting’ toilet break during a Democratic debate) because he is entirely serious about his seeming silliness. “Performance art is a parochial or obscure form, and it’s easier to laugh at something than stop and think about it,” he said.

I was met with a resounding ‘Ah yes’ when I asked curators, artists, performance historians and critics about the performance-art prejudice. According to historian Professor Alan Read at King’s College London, “Performance art’s own turbulent relationship with snide is long running and multifarious.” Indeed, the ‘peculiar’ is often what we mean when we use performance art as pejorative metaphor. “I think it is the way [performance art has] become a shifting signifier for all that is, supposedly, difficult, obscure, elitist, strange, queer, marginal, adversarial,” he said. Are we also using performance art as a conduit to dismiss the queer and marginal, or as Johnson rightly terms it, “that which departs from convention?”

In the early modern period in England, a large portion of anti-theatrical rhetoric stemmed from its divergence from ‘truth’; this was acting and not real behaviour. Anti-theatricalists hated the idea of men dressing up as women and vice versa — they disdained the lies and ultimately, the queer strangeness of the theater. Calling Trump performance art ensures his racist, sexist, homophobic and insidious antics are inoculated, wrongly perceived as ridiculous. Doing so turns a blind eye to performance art’s potential to employ and empower the queer, marginal and radical (which it has a long, wonderful history of doing). Dominic Johnson signed off his last email to me with the following: “Performance art is serious, even when it is not.”

In an episode of Sex and the City, Carrie and Charlotte visit a gallery performance — a spoof of Abramović’s The House with the Ocean View (2002). An Abramović look-a-like is installed for twelve days, and Carrie mentions that the artist “needs to move a comb through her hair — she has company.” Charlotte erupts with laughter and another audience member (with a shaved head, obviously) sends them a death stare. Later, when The Russian, Aleksandr Petrovsky, asks Carrie what she thought of the piece, she replies, “there are depressed women all over the city doing the exact same thing as her and not calling it art. Put a phone up on that platform and it’s just a typical Friday night waiting for some guy to call. Why do you think she has the knife ladders — to keep her from running out for a snack?” Carrie’s line is humorous in the context of Sex and the City, but not eating for twelve days straight is a colossal feat of endurance. It also parodies a real performance that was spiritual, transformative and crucial to the history of contemporary art.

I distinctly remember the first time I watched a documentary about Abramović’s work Seven Easy Pieces in an undergraduate class at King’s College London. Abramović recreates five famous performance art pieces, as well as two of her own performances. The work is terrifying, exhausting and uncomfortable to watch. Recreating Bruce Nauman’s 1972 performance Body Pressure, Abramović slams herself against a pane of glass. She squashes her body and grunts gutturally, her face transmogrifying as she presses herself against the transparent surface, the sound of her skin against the glass creating loud reverberations around the room.

I sniggered quietly to my friend as Abramović made absurd faces like a small child might do in a mirror. It seemed obvious why this work could be so easily ridiculed — how it could become fodder for a TV show. However, as I continued to watch the performance I realized that yes, perhaps I could laugh at this work, but to ignore its visceral, bodily pain would dismiss the difficulty and intended unease of this work. That my reactions were torn and confused was premeditated by Abramović — I was meant to find the work difficult to consume — laughter and pain aren’t mutually exclusive.

Not registering the discomfort, humor, and endurance of Abramović’s performances would deny the importance of this work. Though it is important that we parody performance, it is crucial that we legitimize performance as serious, even when it is not. Before we crack a joke, we should instead embrace our difficulty with performance art and learn to understand it a bit more. (Surely, making jokes without understanding and consideration is simply ignorance?) Performance art often laughs at itself, but this doesn’t mean we should automatically discredit performance art by laughing back; sometimes we need to take it seriously.

Performance art seems to have become shorthand for the obnoxious, but it is worth defending, for the precise reason that it departs from convention. It is crucial that we resist deriding a form that historically predicates and gives voice to the queer, antagonistic, peripheral, complex and radical (For example, seminal pieces such as Franko B’s I Miss You, Carolee Schneemann’s Interior Scroll, Atsuko Tanaka’s Electric Dress, Barbara T. Smith’s Ritual Meat and Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece). Let’s stopping mocking the difficult, or that which challenges us, by subsuming the ‘strange’ with pejorative laughter — let’s take the threat of Trump seriously and let’s give performance art some credit.

Bryony White is a writer based in London, UK. She has written for The Quietus, Apollo, Bust Magazine and Google Arts and Culture.

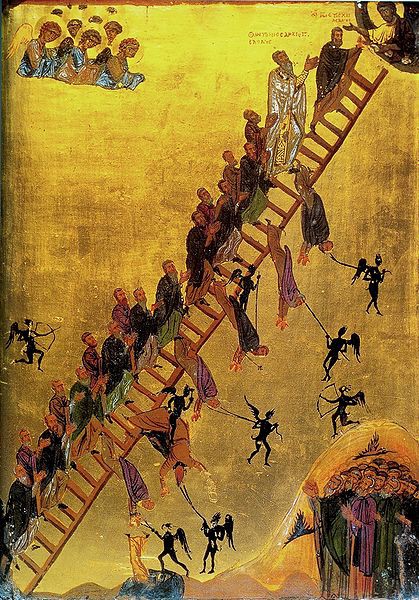

Snakes and Ladders

On Allen Frantzen, misogyny, and the problem with tenure.

“Brain tumor?” the direct message read. We speculated about personality-altering illnesses. I repeated the conversation with other friends, other colleagues. It is not ethical to talk like that. Speculating about another person’s health is indefensible. But what can you do when an academic hero turns out to be, or to have become, all of a sudden terribly stupid?

Allen J. Frantzen is a medievalist, now retired. He’s an emeritus professor of Loyola University in Chicago. He is sixty-eight years old, and in 1990, he published a book called Desire For Origins: New Languages, Old English, and Teaching and Tradition, which sits by my bedside. It’s in the permanent pile (which is next to the reviewing pile, separated by a house plant), because it’s one of those books I think is so good I want it within arm’s reach all the time.

Many people find Old English remote, dull, and boring. Desire For Origins interrogates how that came to be, and Frantzen manages the unusual feat of climbing outside his own field. It’s comparable to the work Edward Said did for cultural representations of “The East” in Orientalism, what Johannes Fabian did in Time and the Other for anthropology.

Frantzen has also contributed remarkable work to the youngish field of queer medieval history, with books like Before the Closet: Same-Sex Love from Beowulf to Angels in America. His work is undoubtedly progressive, which is why recent revelations were so stunning as to lead to speculation about personality-altering illnesses.

Follow the internet trail to Frantzen’s personal website, and you’ll find a series of misogynistic screeds peppered with the most hackneyed and useless men’s rights activist jargon you could imagine. It was uncovered by other medievalists last year, and I came across it after Jeffrey Cohen, a professor at George Washington University, tweeted about it:

Allen Frantzen (<– medievalist) is an embarrassment to medieval studies. http://www.allenjfrantzen.com/Men/femfog.html

Frantzen’s reputation first began to shatter within the medievalist community, and ended up as far as the pages of the Chronicle of Higher Education, even Jezebel. The precise page Cohen links to in his tweet has been deleted, but the language used in it, specifically the term “femfog,” sparked ongoing widespread hashtag ridicule.

In a blog post at medieval internet concern In the Middle, Cohen reproduced a section of a now-deleted page of Frantzen’s site, summarizing “femfog”:

Let’s call it the femfog for short, the sour mix of victimization and privilege that makes up modern feminism and that feminists use to intimidate and exploit men … I refer to men who are shrouded in this fog as FUMs, fogged up men. I think they are also fucked up, but let’s settle for the more analytical term. These may might not be feminists but as they wander through the mist of politics and polemic about women, they feel like they should be feminists. They think feminism is good for everybody and they want to be nice to women … My aim in this RP essay is to help you clear the fog of feminist propaganda. Grab your balls (GYB) and be the man you want to be.

A search of #Femfog on Twitter turns up results both funny and deadly serious, and there’s going to be a scholarly panel on it at this year’s big medieval conference in Leeds.

Frantzen espouses ‘masculinism,’ and presents faux-academic arguments for rejecting feminism wholesale as a kind of hegemonic delusion (the aforementioned femfog). He uses MRA terms like “red pill” and “compulsory feminism” and refers to the supposed “fog of WAW (Women are Wonderful) feminism pumped out by the media and politicians.” He cites data in a bizarre parody of scholarly rigor, footnoting and dividing his argument into sections, then writes in the second person.

Like some kind of malevolent advice columnist, Frantzen teaches the would-be ‘masculinist’ to counter his feminist friend’s arguments by suggesting a reading list. “You don’t need to read the whole of these books,” he says:

My bet is that the first few chapters will kick your ass, and that’s all you need. If at any data-related point the feminist challenges you (“That’s not true,” or “I don’t believe that”) check her (or his) credentials. Do this by asking a question: “What have you read about this? Do you have other information, or is that a hunch or perhaps your reaction to a point of view or some data you have not heard before?” Chances are good they will not have data. Press on.

I’m not sure what the strict definition of “hero” is in today’s world, but the author of a book that I keep on a bedside table must be mine. This particular hero has turned out to be a cartoon villain. Medieval literature is usually more subtle than that: fortune’s wheel, which dictates the rise and fall of kings and emperors, turns slowly. It doesn’t spin, or unexpectedly explode. I don’t really have the strength to unpack everything that Frantzen wrote on his site. He’s gay, does that matter? I don’t know. It’s mostly very sad.

The medieval studies community has reacted in a calm and collected way to this nasty event. I’m not worried about the discipline, which is led by ferocious women and brilliant human beings of all genders and identities. I am worried, however, about a workplace in which the tenured, particularly men, are exempt from the kind of character scrutiny to which ordinary employees, especially women (cis, trans, or otherwise), are subjected to in almost every other profession.

In a blog post about Frantzen, Cohen said, “Even as I write an email arrived telling me that I am being ‘extremely unprofessional’ for condemning this writing.” Where is the outline of professionalism for a high-achieving professor and why can’t anybody show it to me? Did tenure protect Allen Frantzen? Tenure means different things depending on context: there’s the tenured professional, then there’s the tenured social individual.

Tenured professors can get fired; immunity from disciplinary action is a myth. Having tenure just means that, if your department wants to fire you, they have to do it in a very slow, well-reasoned, well-proven way. Not all tenured professors are untouchable despots. Cohen is right that, in one sense, the it isn’t the “the profession or its structures” which are to blame. He emphasized “that Frantzen was a lifelong misogynist who carefully kept himself in check until after retirement — so he knew tenure would not protect him all that much with his MRA views.” Still, Cohen says, this is a conversation that we could have had long ago. So, why didn’t we?

From my perspective (far lower down the academic ladder), a tenured professor’s behavior is not subject to sanction, under almost any circumstances, because of the weighting of power in the hierarchy of academic relationships. Not every academic who has hit on, harassed, or propositioned me has been tenured or published influential work, but most of them have. The power that those men have is not derived from their position in HR terms: it’s derived from their position in community terms, the extreme concentration of power that holds up the tenure throne.

Everybody wants to impress a titan in their field. I remember once staring into my coffee, looking at the bubbles at the edge, realizing that a man I had yesterday thought was a god had grabbed my ass while his wife was in the room, not even that far away. What did I do about it? Nothing, including re-evaluate his scholarship. I’ve talked about it with a few people. But he’s fun, and his work is so good, and he’s so senior. There’s nothing substantial there. What would I take to his department? I’ve got nothing. His character isn’t subject to scrutiny; his research is.

Academia accepts the substitution of scholarship for character. This is a bug, not a feature. Cohen pointed out that that tenure provides “the potential for intellectual isolation,” in that it rewards “solitary achievement over collaboration, pioneering over making together . . . and it is easy to drift into some scary places without reality checks to bring you back.”

When we study Animal Farm in middle school we learn that power corrupts. But we can be more specific than that — it’s the trust element of power that corrupts, in the academic context. Peer review is based on trust, teaching is based on trust, tenure is based on trust. Trust is the substance that begins the corruption, and it corrodes when it comes into contact with vulnerability (or hatred, or whatever is eating Allen Frantzen).

So, what are we left with, now that Frantzen has posed a bunch of unanswerable questions then scuttled off into retirement, beyond interrogation? We have a reminder, I suppose, that very clever people can harbor pockets of extreme dullness within their brains. Intellects can be archipelagic. Frantzen’s misogyny also endorses some of my own decisions. Working at the bottom of the academic ladder can be lung-crushingly frustrating. The people at the bottom hold the whole thing up and, if they want, the people at the top can swoop down and abuse you and never even wobble.

I explained all this to a friend over a beer the other day, and it dawned on me that I was free. Not free of the need to grind for money or to work hard, but free of that particular ladder, that particular weight on my chest. I never saw the joy in freedom before. I preferred captivity, because its crush felt loving. But now it’s just me. I don’t have to worry about being ‘extremely unprofessional,’ because I don’t have a profession, except what I’m doing right now, giving voice to the new weightless feeling that Frantzen accidentally pointed out that I had. Not all fogs lift, but some evaporate just as soon as you look around.

Josephine Livingstone is a writer and academic.

A Poem by Laura Kolbe

Other people’s boyfriends

wearied of mishearing “gins”

as “chance” at the watering hole, as in

take-slash-have one. As in on me. Wore

out their zonked cigarettes

tacking z-routes like pumpkin teeth

across the parking lot;

worked out, repentant, in cone-bra

shaped fitness temples. Got hard

and wary. Were, in this sense, mine. As in

take one. I am what every O.P.B. wants: a bullet

list on the phone screen, a what-

shall-we-do. I never confused

what meant “book” and what meant “free”

in mouthful Latin mottoes.

I was never “book.” O.P.B.s waded

like flamingoes into the scum

of my room. Wore, in a sense,

my jeans. In the light of abundant,

me-shaped clarity, they wrote

their first poem. As in “rides on

its own melting.” A burn that was,

for some, more like being alone.

Mornings: no-face pancakes, blankets blank.

Coffee mugs of sour wine,

handles pert empty nerveless ears.

All signs pointed away from “listen”

out to sea. This is when I was sold

on O.P.B.s: when I held my skull

to their chests, I heard China, magma,

the dark side of a personal moon.

That is, my blood flipped back on me.

When they dug their conch heads

into cars, I sealed them away

with all the haste of Novocain,

the grudging splurge of a Carmike seat.

My mind’s eye dyed their hair

submarine. In bad straits, their warheads dove,

a woeful plume, a wave, in this sense, mine.

Laura Kolbe’s poetry and prose have appeared or are forthcoming in AGNI, The Cincinnati Review, The Kenyon Review, Prairie Schooner, Virginia Quarterly Review, The Yale Review, and elsewhere. She practices medicine in Boston, Massachusetts.

The Poetry Section is edited by Mark Bibbins.

Whither The Webpage

Does it even matter what a website looks like anymore?

It only happens from time to time, but even today one will, on occasion, find oneself on a webpage. An honest-to-God site. It can be a disorienting experience. Where is the home button? Where is the hamburger menu? Where is my profile picture, and chat box, and why are the links broken, and why does this all load so slowly?

Chances are good you’re reading this particular piece of content on your phone, through a smoothly-loading feed. That’s okay! This is neither quantitatively unusual nor qualitatively bad, it’s simply the way things are. It’s now well established that most internet users experience the web through a handful of large, enclosed platforms and apps. We’re fast moving toward a majority of Americans getting their news exclusively through a Facebook feed. (Or maybe not!)

If the internet is trending toward commercial consolidation and monopoly, it shouldn’t really surprise us that this would also mean a monopolization of its affect, its look and feel, too. It’s no wonder websites look the same now; they essentially are the same thing.

Was the Early Web any better? The pre-platform, pre-mobile internet was a web of pages and links and counters. The most essential thing about it is the notion that it looked bad. But the bad-looking web is making a comeback. All of a sudden you’re on that clunky-looking webpage again.

A recent Washington Post piece focused on one Swiss designer’s designation for the bad web renaissance: “Web Brutalism.” Pascal Deville collects examples of web brutalism on brutalistwebsites.com, itself a kind of brutalist template, which highlights some of the web’s best worst design.

As with brutalism in architecture, these sites use their infrastructure as a design element. Some, like Bloomberg Businessweek, are the product of extremely web and art-conscious designers. Others, like Drudge Report, are kind of outsider brutalists — the Paranoid Crank Style in American Web Design.

That anyone still bothers to build homepages at all should be heartening, when it’s both easier and almost surely more financially rewarding to post something directly to a social network. But from a design standpoint, all web brutalism seems to mean is a turn away from the affective onslaught of the gooey, bubbly skeuomorphism of Web 2.0., and a rejection of the streamlined, blue superflatness of the Zuckerbergian web, in turn. Deville’s examples of web brutalism run from the Geocities-adjacent to weird little single-servings to meta jokes to Craigslist.

So while web brutalism might not refer to any one specific design aesthetic, it still seems to pick out a certain kind of website, not a look so much as a feel. Web brutalism might even be an important way to conceptualize the internet. Why not? Independent web publishing (ahem) is still important, and its operation separate of larger commercial interests becomes even more important in our contemporary Hogan-Thielscape.

A few smart people saw it coming. Steph Davidson is an artist and designer at Bloomberg Digital. She is a prolific maker of websites. Davidson and the Bloomberg team are responsible for the consistently great and weird design of the print Businessweek, as well as its web features. It has always seemed both fitting and unlikely that late capitalism’s trade mag would so often look like an elaborate Dada prank.

Businessweek’s design might seem like proof that web brutalism has arrived in the mainstream. But Davidson doesn’t put much faith in the phenomenon, at least not as it exists in Deville’s world. In an email, she wrote, “I don’t think web brutalism exists…A lot of this style comes from net art, sites from 8 or 10 years ago, like paper rad, google with 53 o’s, rhizome, maximum sorrow, spirit surfers, nasty nets, tumblr and so on.”

aesthetics is a prison

So to what extent does the way a site looks impact what a site is? This question might have to be re-legislated again. What seems certain is that fewer discrete pages means fewer discrete voices, and further ensures that the internet becomes primarily a vehicle for reaction (and all the ugliness of a purely reactionary culture) rather than creation.

Nostalgia for the way the web looked is really a sublimated nostalgia for how it felt, for a time in almost everyone’s life when discovery and openness and joy were all more operable. As much as we want to preserve the early internet in amber, we want to hold on to the feeling of the early internet even more.

The web has a kind of archive fever recently. Contemporary projects like Deville’s site, GeoCities Forever, One Terabyte of Kilobyte Age, or Web Safe 2K16 are, in very different ways, creating web archives of affect. The bad-looking web was also the earnest-feeling web. A strong undercurrent of fandom and eagerness and joie de vivre sustained it. Internet “maker culture” promised to efface geographic and demographic identity in favor of affinity. Whether you were a collector of vintage gardening equipment or an amateur whittler or a Roswell conspiracy theorist — the web would, the idea was, allow for your flourishing, and the primacy of hobbyists, enthusiasts, autodidacts.

The appeal of the hand-made webpage remains its openness to whatever niche, obscure hobby or interest you might have. “The fact remains: Anyone can create a home page!” Paul Ford, a writer and technologist, told me in an email. “God please show me more home pages with goofy graphics from strangers instead of random Facebook updates,” he wrote.

As the investor class pivots toward video, the web actually stands a decent chance of becoming more disjointed and oddball and ecumenical in its design, and in turn more spontaneous or creative in its spirit. A closer visual link to ordinary, lived reality has some promise. Perhaps life on the internet will better resemble the dizzy phantasmagoria of life in a physical reality. A live stream is less curated, more amenable to chance and contingency.

But! It also stands to replicate the worst aspects of television: passivity, mediocrity, a plurality of superficial choice with the same indistinguishable affect. Not to mention new sorts of vacuity and horror specific to a post-platform age. I don’t know a lot about virtual reality, but I’m told to prepare myself not for ads but for “branded experiences.”

The television model puts a premium on persona over personhood and the old complaints become new again (get ready to say that you don’t even own a streaming service subscription). An internet premised on the stream will probably prompt new forms of nostalgia: to just explain oneself in writing for once, in a multi-paragraph Facebook update, like the good old days. Either the coming video model finally calls the internet’s democratic bluff, or it ushers in a brave new era of millennial Vine-celebrities in the House of Representatives, gleefully rebuilding a social democratic welfare state, passing sane gun control legislation, and breaking up the banks while GoProing their water-bottle flips.

Ford and his colleague Rich Ziade theorized on their podcast that hand-coded, early web technology may someday work like organic food, earning a little USDA certification label. Users, the idea goes, have a right to know what they’re getting themselves into. Platforms and feeds don’t do much to distinguish between reported news items, recycled memes, “Epic Rants,” and branded, commercial content—publishers themselves hardly seem to make an effort. A (non-premium) cable television analogy might also be helpful here: as long as we’ve declared high-speed internet a public utility, we might as well insist on a C-SPAN.

Charles Thaxton is a web producer at JSTOR Daily and a freelancer elsewhere. He’s on Twitter @thaxromana.

Magical Mistakes, "Chemical Bath"

Look out there on the horizon: It’s the finish line to the week!

If you can make it through today — and I have faith that you can, you are much stronger than you give yourself credit for — you will find yourself at the Friday before a three-day weekend, and we know how little gets done on those days. You’re SO CLOSE. Just push on through, and you will have well-deserved respite, however brief, from all this horror. Hold your nose and jump in.

Meanwhile, I’m not going to lie to you: The track below will probably not change your life. Few things do. But it is certainly pleasant enough, and that is probably all you can expect for now. Changing lives is a such a lot of work in any event, you might want to wait until summer is over to work on that. In any event, enjoy.

New York City, June 28, 2016

★ The roaring of the air conditioner all but drowned out the beeping or chiming of the phone alarm clock, and the dim gray light kept the brain from rousing enough to notice. The air outside was so soggy it was hard to believe it wasn’t hot. Uptown and downtown, the buildings were truncated by white fog. Then a heavier darkness came down, crushing the afternoon. Where there should have been the long bright summer evening, there was only renewed and grayer fog to speed and intensify the fall of night.

Why We Tweet

The answer is actually very simple.

“Why,” asks Slate’s Katy Waldman, “do we feel compelled to tweet about our most embarrassing moments?” It’s a good question. Would you like to know the answer? Here it is:

We are compelled to tweet about our most embarrassing moments for the same reasons we are compelled to share everything else we send out onto the many channels of self-promotion through which we now craft the personalities that we previously constructed around achievements, affiliations and examples of actual effort. Those reasons are, in no particular order:

- We want people to notice us.

- We want to feel like we are part of the conversation.

- We hope people will like (and “like”) us.

- We wake each morning with a vague feeling of unease that we cannot quite bear to admit is the only rational response to the knowledge that our lives are finite and the things we do with them each day are meaningless gestures designed to distract us from the futility of every effort we make to fight against the unceasing vagaries of an uncaring universe. This persistent pain, made ineffable by the similarly unspoken knowledge that to address it would be to admit to the absurdity and emptiness of existence, causes us to act out and do anything we can to elicit the acknowledgement of our equally damned companions in this parade into the void, a yearning for validation so desperate that something as insignificant as a series of digital hearts temporarily soothes the ache.

- We don’t know or care about the difference between “good” and “bad” attention.

There are probably some other answers in the Waldman piece, but basically it’s the “we’re all going to die and our lives are so wholly lacking in meaning that we cry out for any sign of recognition, no matter how cheapened and valueless” thesis. The rest is details. Please like and share this.

Reality Hunger

How Big Food manufactures authenticity in an artisanal world

A.1. Steak Sauce, never artisanal and not once locally made, is currently the subject of a campaign that touts it as a secret ingredient to a compound butter with which to finish your steak. It’s a very straightforward commercial: no fancy CGI talking steaks, no dizzying smash cuts, just a peppy-but-smooth voiceover narrating a recipe as a handsome-but-friendly young man in a chef coat makes a butter with A.1. rolled into it, and then makes a steak that is then finished with a knob of said butter. The final image is the product and, whoa — correction, the product is not A.1. Steak Sauce but now A.1. Original Sauce. Because what self-respecting foodizen would buy a mass-produced product just to pour it onto a steak? This is no longer a condiment (a condiment that goes back to 1831 in what we then called “England” whose secret ingredient is raisins, shh) but a fancy home-cooking ingredient to be integrated into your haute cuisine while you sip blue wine and make Tronc jokes, wittily.

It wasn’t that long ago that chocolate bars made from cocoa beans sailed to the States on a three-masted schooner were some sort of novelty, and the word locavore was designated a word of the year. But as foodie culture has matured and become less an underground movement, commercially mass-produced food products swollen with HFCS and other test-tube names — along with the small number of multinational food and beverage conglomerates, such as The Kraft Heinz Company (which is what remains after a series of mergers and acquisitions of formerly independent and iconic companies, and not coincidentally the owner of A.1.) with concentrated influence, sometimes referred to as “Big Food” — haven’t exactly gone away.

We live in an age of high-end food magazines and journals actually starting and not shuttering, and an entire sub-industry of TV shows with adorable tykes cooking for judges, a time when everyone has at least one friend who tsks when you disclose that you use dry yeast and not a home-cultivated starter to make your Asiago Di Parma babka sticks. How is Big Food keeping on keeping on, and how do they like Twitter?

Food is better than food has been ever before. Ask anyone! Or go have some food, perhaps at a pop-up or a food hall. After a long omnipresence of industrially manufactured shelf-stabilized product, better and healthier food is slowly making its way to more and more tables. Big Food has for better or worse largely solved issues of food scarcity in America — in the historic sense of growing/manufacturing and eventually processing enough calories that will not spoil before it can be delivered to an entire nation. (This victory over scarcity is not to be confused with food deserts, which are in many ways the intended result of Big Food’s ubiquity.)

But all is not so sanguine in the boardrooms of Big Food. In fact, they have a multibillion-dollar problem: consumers are looking for, and buying, alternatives to the processed, packaged, middle-aisle foods that have been so popular for so long. Packaged-food sales in the U.S. are falling at a rate of 1% a year, which doesn’t seem like very much, unless you are a brand manager for Big Food. At the same time, annual sales of organic food are increasing at a steady clip. Consider annual sales topping $100 billion for the first time in 2014 for the “specialty food industry” (generally speaking, small purveyors of upscale food products/fancy hippie stuff). In that same year, 82% of those sales were made in mainstream stores — your Walmarts and Costcos and drug stores and grocery chains. The fancy hippie stuff that used to haunt the co-op or the local health-food store for is increasingly bought and sold in places where Big Food once had no competition.

Since 2005, Americans have been making healthier food choices, reflecting efforts through advertising and product labeling to make consumers aware of the nutritional value of whatever is for lunch and dinner. Meanwhile, a robust foodie culture buttressed ideas of wellness in food with a patina of authenticity. Before there were foodies, there was a near-century of home-kitchen gourmands, like M.F.K. Fisher and Julia Child and James Beard (and even Vincent Price!). First with the written word and later with television shows, they pushed a proto-DIY sensibility about foods that were traditionally the province of fine restaurants. By the end of the Reagan years, the Slow Food Movement coalesced, a quiet revolution against fast food and fast life (and, in a sense, modernity), bringing what could now be called a concept of self-care into gastronomy.

And this authenticity has blossomed into the food culture we know now — an army of heavily tattooed chefs willing to risk being Chopped, followed from opening to opening (to book-signing) by a food-buying public right behind him or her that increasingly wants to eat less processed, fresher, and healthier food. Americans are now looking to food to provide something more than convenience, whether sustainability, health, cultural cachet or extravagance, all aspects of authenticity that can be summed up as, “Not Big Food.”

One tactic of Big Food in reacting to a consumer sentiment leery of Big Food is to go out and subsume specialty and organic food manufacturers into their conglomerate maws like so many chili-cheese flavored baked corn potato snacks. True, some of the organic food companies have sales numbers that put them in the same league with traditional food companies — Hain Celestial Group (Celestial Seasonings, Spectrum coconut oil) booked $752 million for the first quarter of 2016, and Bob’s Red Mill is estimated to pull in $200 million per year. But many of these heavy hitters play for the other team. Alexia (gourmet frozen foods) joined ConAgra in 2005, and Blake’s All Natural did the same in 2015. LaraBar landed with General Mills in 2008, Stacy’s Pita Chips has been part of PepsiCo since 2005, JAB Holding Company acquired luxe coffee concerns Stumptown and Intelligentsia in 2015. And in the most extreme example of dissonance, presumably “natural & organic” meat purveyor Applegate Farms was acquired by meat processing giant Hormel Foods in 2015. If you can’t beat ’em, buy ‘em.

To the extent that authenticity cannot be purchased, Big Food is trying to surf it. Legacy food products, filled with efficient ingredients developed over generations for ease of manufacture, product shelf stability, taste, etc., are being changed: synthetics removed, and artificial colors eschewed. In some cases, the recipes are tweaked in an effort to transmogrify the irretrievably dated food product into something cool, or at least approaching cool. Take for example Hot Pockets, which have collaborated with food trucks to roll out a new line called Hot Pocket Food Truck Bites (Triple Cheesy Bacon Melt Bites! Spicy Asian-Style Beef Rollers! Etc.), a clumsy name but a very earnest co-optation of foodie culture, brought to you by the Nestlé Pizza and Snacking Division, Nestlé USA, which is also a clumsy name but at least transparent. Big Food getting into the Stoner Stunt Meal business is nothing new (especially in the fast food sector), but Hot Pocket Food Truck Bites simultaneously achieves full munchie while lolling under the umbrella of food truck authenticity — i.e., yes it sounds gross; would eat.

One iconic dry dinner-mix brand that finds itself at this particular crossroads is Hamburger Helper (which by the way is now known as just “Helper.”) Three years ago, General Mills updated the brand to “appeal to Millennials,” such that the Tuna Helper and the Chicken Helper joined Hamburger Helper as just plain Helper. This is not to be confused with an indie rock band. Or is it? But it is a deft little transition from pure nostalgia, all orange vinyl and fake wood panelling, to a swell foop of attempted memetic content, something that is easy to imagine as a favicon or an app button.

A few months ago, Helper dropped a mixtape called Watch The Stove on Soundcloud. Even assuming a baseline of news-aggregation churn, it grabbed some headlines and murdered some favs. As of this month, the first track has been played six million times, while the last of the five tracks has hit close to 600,000. Thought it was release on April Fool’s Day, it was well received, with some critics noting that it was “among the year’s best mixtapes” and “pure goofy fun” and “shockingly great”/”shockingly good.”

It did not take long for the official version of the secret origin of the HH Mixtape to hit AdWeek (and a bit longer for the music-focused version to run): General Mills has a scrappy if not heroic in-house agency dubbed The BellShop. “Our creative officer was like, ‘Trust the kids, let it happen,’” communicated Liana Miller, marketing communications manager. Of course he was! “Let’s make something we would listen to, not some marketing ploy,” said the Millennials in the house. A little ingenuity and a half-dozen or so “up-and-coming rappers and social influencers” later, and voila, a little widget full of music and fun and authenticity was unleashed to adoring fans.

Authentic, you could say, which circles us back to where we started. An aging Food Product — which actually can never be retro-locavored or whittled into some version of bespoke because it was always intended to be a convenient food from a box and not a twinkly dream-catcher of nature’s bounty — is dragged into authenticity by the authentic efforts of some authentic ad kids who authentically love rap music.

Or is it Authentic, but in scare quotes? As the Minnesota Star-Tribune reported on the brand reinvigoration in 2013:

Mills plans an advertising blitz for Helper starting this month. The campaign will include digital, a space in which General Mills is often aggressive, but hadn’t been with Helper. The brand got a Facebook page only in December. Digital would seem vital as General Mills tries to broaden the marketing of Helper to a younger demographic — 20-somethings, particularly men.

As recently as June 2014, this relaunch was not going so well. Helper specifically was lagging, showing no increase from the sales numbers that inspired the Helper-ification of Hamburger Helper. Eighteen months later, creatives scurried around Minneapolis, lining up tracks honoring the dry-dinner mix.

Another bit of history that makes this cheese more binding is that, among the upscale gourmet concerns bought by General Mills was Annie’s, in 2014. And while it might turn your stomach to know that your dollars supporting gluten-free goldfish-shaped crackers are actually going to Big Food, it could not have gone unnoticed by the Helper crew, as the prepared macaroni-and-cheese product that supplanted the blue boxes of Kraft in so many homes, the market-gobbling competitor to Helper, was now married into the General Mills family. Helper was increasingly the odd cousin with funny taste in clothes that the second and third cousins whisper about.

Does the fact that this accident of authenticity was not so accidental make it any less authentic? In a sense, the question is analogous to, “Does knowing how the sausage is made make it any less sausagey?” But sausage does not purport to be anything other than sausage, and if authenticity really is manufactured, then that’s a bit of conceptual crossing of the streams, which brings us to the central question of whether a Big Food food product can still have it all in these modern times.

Compound butter is not the first non-steak use that has been marketed for A.1. In the 80s, there was a protracted campaign imploring America to put that stuff on a burger, and in 1963 A.1. ran a truly visionary spot with many hors d’oeuvres suggestions, including a “cream cheese sundae” that is nothing but a pile of cream cheese with A.1. as the “fudge” — for dipping! Big Food was crafty about how to trick people into buying their product even back when it was a bunch of Little Foods, and there is always a peg, like affordability, or flavor, or convenience, that this advertising and marketing is hung on. The pervasive such peg right now is authenticity, and as we navigate what’s for dinner, we are confronted with questions of authenticity, whether intrinsic or bestowed.

And the authenticity of Helper, or A.1. Original Sauce, or Hot Pocket Food Truck Bites, is as authentic as every other artifact of a non-authentic time. Faking it is the new bringing it, and it’s not just the hundred or so thousand people who know what a “tech bro” is who are now the targets of creative class employed by Big Food (who also know what a “tech bro” is), but rather the millions and millions of consumers who follow behind, who just want to listen to a mixtape and think to themselves how turnt/lit/woke it is that there’s a Hamburger Helper mixtape. There are forces of capitalism at work here, or at least forces of greed. General Mills isn’t going anywhere, in the same sense that The Banks aren’t going to spontaneously break up.

Helper and A.1. could be retconned out of existence and the world would keep turning. When discussing issues of nutrition or sustainability, the fates and fortunes of Big Food legacy products are irrelevant, but for the fact that they actually do exist and presumably people are employed manufacturing and marketing and distributing and retailing them and a bunch of people certainly like eating them — I like eating them. Five years from now, there will be another course of events that will be take-worthy concerning Helper or Hlpr or whatever the name morphs into, at which time there will still be fans listening to “Watch the Stove” and reminiscing.