New York City, July 6, 2016

★★ A solitary little cloud, hanging in the sky a few degrees west of north, grew and loosened and tightened and shrank again till it had all but dissolved, in a span of no more than 20 minutes. The sky below it was stained grayish rose. The video screen in the elevator carried a heat warning, making the nine-year-old fret all the way to and from the trip to the coffee shop and the hot dog place. Ambitions of going anywhere else seemed not worth raising. A pair of pink sneakers, unmoving, stuck out from under a white gauze shroud on a stroller in the elevator back up. By midafternoon, boredom had overcome anxiety and discomfort, and the boys squabbled their way to an agreement to play wiffle ball on the schoolyard. Other activity on the playground was sparse, but not too sparse to allow first one stranger, then two more, to drift over and attach themselves to the batting order. The shade covered all of the painted infield but second base and its vicinity; by agreement or conspiracy against the unassisted grownup pitcher, the batters resolved to stretch or steal their way from first to third at every opportunity. Now and then, one or two of the newcomers would put in a shift in the outfield, so that not every line drive had to be chased into the far sunny reaches. After three one-sided and high-scoring innings, it fell to the pitcher—having earlier promised to protect the children from heatstroke or heat exhaustion, back when they cared about such things—to call a halt. Back at home, a freshly emptied seltzer glass spread its chill into the forehead when pressed there. The four-year-old, watching the process, wanted to try it himself. Then he put the glass on the air conditioner vent to make it colder.

No Country For Its People

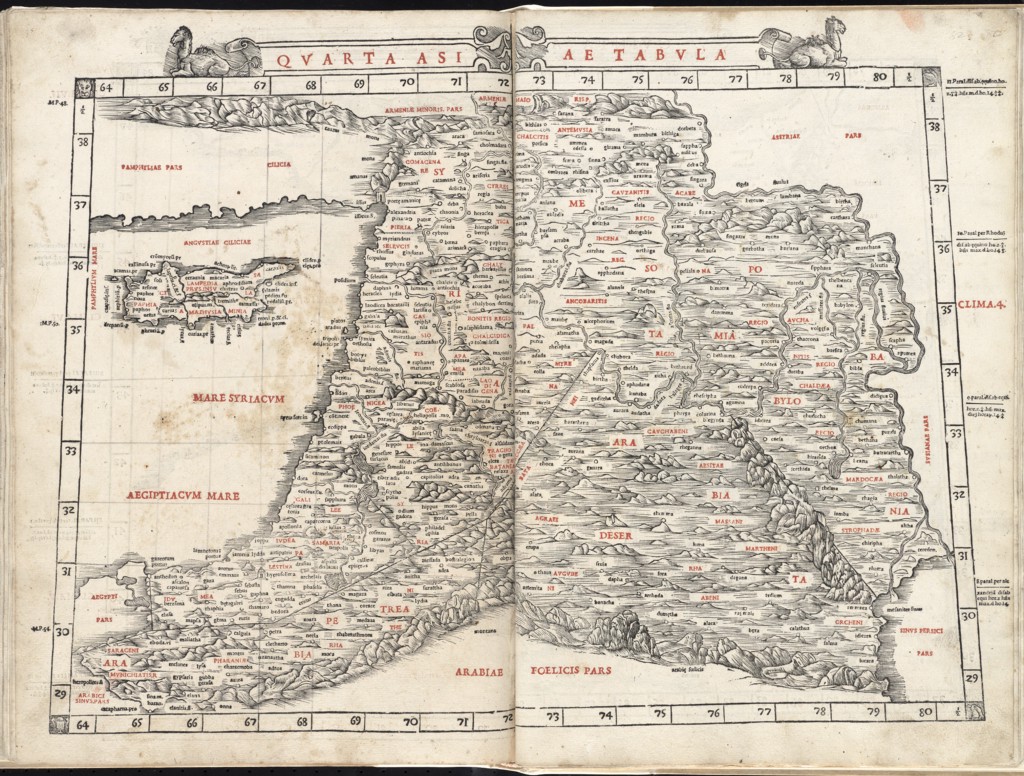

A short history of modern Iraq’s ethnic minorities

“…an Iraqi people does not yet exist; what we have is throngs of human beings lacking any national consciousness of sense of unity, immersed in religious superstition and traditions, receptive to evil, inclined towards anarchy and always prepared to rise up against any government whatsoever. I have begun with the army because I consider it to be the backbone for the creation of the nation.” — King Faisal I, 1932

Iraqi society has never been more disjointed than it is today. The long decade since the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003 has pulverized relations between the country’s communities and decimated its smaller populations. The emergence of ISIS led to demographic and territorial disfigurations so deep that even attempts to reverse them could move the country further away from any sort of meaningful coherence. The dream of an ethnically plural Iraqi state is now an even more remote prospect than it was upon the country’s foundation as an independent kingdom in 1932.

From the outset of independence, the Iraqi Army swiftly set about straightening Iraq’s backbone, roving across the new borders of the state with demonstrations of force. The new country’s Sunni-led government crushed uprisings led by Kurds, Yezidis, and Shi’a tribes. In 1933, three thousand Assyrians were massacred in a series of rampages as the nascent Iraqi army slaughtered their way through villages in the north. The military quickly emerged as the only institution capable of cohering the country, and violence became the principal ideal of Iraqi governance.

The belief that Iraq was an Arab state — and that its citizens should either become Arab or be punished for not being so — became the guiding principle of social control. Groups within Iraq but not loyal to its rulers have long been construed as fifth columns: the Shi’a, for their allegiances to Iran; the Assyrians, for the assertion of their indigenous ethnicity, their ties to the British, and their ambitions for autonomy; the Kurds, for placing their own interests above those of the state; and the Jews, for participating in the international Zionist conspiracy.

The militarization of Iraqi politics led to an extensive history of coups and counter-coups; Saddam Hussein took over in 1979 after a few more. Saddam’s Ba’ath regime hailed the resurgence and unity of a superior ancient race (the Arabs); pursued the righting of wrongs suffered under foreign influence (e.g., the annexation of Kuwait); exhibited ruthless disdain for all other forms of political organization, especially communism; and was profoundly anti-Semitic. Non-Arabs were expelled from ethnically mixed areas, largely in the north, their property seized and destroyed, and replaced with Arabs. The Kurds were eventually targeted for annihilation.

Following the toppling of the Ba’ath regime in 2003, western state-crafters largely turned to exiles to run the country. Many of these men had been banished from Iraq by Saddam when they were young for opposing his rule, and spent the subsequent decades in states of paranoia and intellectual stagnancy. The scene was set for them to unleash their blinkered partisanship and aggrieved sense of righteous destiny into the new Iraq.

The leaders of the Iraqi Governing Council, the transitional authority from 2003–4, began de-Ba’athification, which saw prominent officials and thousands of rank-and-file employees loyal to Saddam removed from office and barred from participation in the new Iraq. Under the auspices of Paul Bremer, the American architect of the occupation, the core of the state was gutted. The returning exiles atomized the Sunni presence in Iraq — in 1922, a year after Iraq was created as a League of Nations mandate, not a single Shi’a was in its provincial government; by 2006, as ethnic violence tore Baghdad apart, only one out of fifty-one members of its provincial council was Sunni.

One of the central tasks of Nouri al-Maliki, Iraq’s Shi’a Prime Minister from 2006 to 2014, was to rebuild a national army. But he refused to integrate the Sahwa militia — a popular Sunni force that had subdued al Qaeda in Iraq — fearing a loss of influence over the security forces, and filled the army’s ranks with Shi’a loyal to him. Maliki had Sunni leaders imprisoned and executed, accusing them of perfidy and sundry crimes, and invoking the de-Ba’athification laws, which could be applied in a highly elastic manner to marginalize or persecute nearly anyone.

Today, preachers foment vicious sectarianism on the streets of Baghdad, directing the alienation and suffering of Iraqis towards perpetual righteous fury. Sunni jihadist groups target the Shi’a population and mosques with waves of car and suicide bombings. Shi’a symbols — images of Ali, the al-Sadr family — are publicly displayed as if those of the state, and Shi’a nasheed — jihad hymns — blare out of government buses. The Mahdi Army, a death squad loyal to the Shi’a demagogue, Muqtada al-Sadr, set about ridding entire Baghdad neighborhoods of Sunnis. There are several maps depicting this demographic cleaving — one includes Christian neighborhoods — but the most important ones show the crucial decline of mixed neighborhoods.

Iraqi leaders have woven the country’s narratives around their hatred for one another. Their tussle for control over communities and the country has come at the expense of both. For Iraq’s smaller peoples — such as Mandaeans, black Iraqis, Assyrians, and Yezidis — this brutalization has taken a disproportionate toll.

The Mandaeans practice an ancient gnostic religion. Their name comes from the Aramaic for “knowledge.” (They are also known as Sabians — the root of which, sba, is Syriac for plunge or bathe — in reference to the central place of baptism in their religious culture). Submersion into water is not merely a sacrament, as in Christianity, but a rite that accompanies the majority of Mandaean rituals, including marriage and preparation for death. Ancient inhabitants of southern Mesopotamia, they have largely been confined to the marshes, channels, and deltas of Khuzestan and Basrah with successive persecutions.

Mandaeans have their own language and scripture, which is close to the dialect of the Babylonian Talmud. Their alphabet adds two letters to the twenty-two usually found in Aramaic. Alap (written with a circular glyph) begins and concludes their alphabet, signaling the wholeness of the twenty-four hours and the perfection and completeness of the universe. They were silver and goldsmiths, and in the twentieth century, many moved to Baghdad and became doctors and pharmacists.

There were sixty to seventy thousand Mandaeans on the eve of the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003; following waves of kidnapping, rape and murder, only a few thousand remain. Knowledge of their faith and written language is confined to their priesthood, and the clergy is dwindling. Their diaspora threatens the continuity of their traditions: Sabian architecture — manda — must be built on flowing (“living”) water, which serves as their sacred space. This is often a problem in the various major western cities in which Mandaeans seek asylum, and where water is too dirty to be used for rituals. For Mandaeans, water is a symbol of God: the source of wisdom, birth and renewal in the universe. Their communal severance from it is a symbol of their disappearance.

Iraq has a significant population of black African descent, concentrated mainly around Basra — a predominantly Shi’a province that produces significant amounts of Iraq’s oil, near the ports settled in waves across centuries of slave trading. Many still practice aspects of the heritage they brought with them, from healing and mourning rituals to spirit summoning and African dances and instruments. Like African-American slaves, they built cities, staffed the homes of the rich, and worked on plantations and farms. There is even a parallel controversy over the word Arab Iraqis use to term them — Abd, slave or servant — the modern, casual deployment of which speaks to an ongoing legacy of racial inferiority. No black Iraqi has ever attained a government position; most work menial jobs, washing cars or providing local private security for businesses.

Black Iraqis do not have their own ethnic quota in Parliament, unlike almost all other ethnic and religious groups in Iraq. Come election time, Sunni and Shi’a parties lure them with bribes and gifts in exchange for oaths swearing allegiance to Allah. Inspired by the Civil Rights Movement and further emboldened by the election of Barack Obama, black Iraqi community leaders tried to mobilize their communities. Jalal Diyab, founder of the Free Iraqi Movement, lobbied to get black Iraqis on provincial councils — and most significantly, he sought to have blacks represented as a discrete ethnic block in Parliament, where they have never had a representative. He was shot dead on April 26, 2013. No investigation into his murder took place, and the other candidates of the Free Iraqi Movement withdrew from the local council elections.

Assyrians trace their heritage to the ancient Assyrian civilization, which also encompassed the state of Babylonia in today’s central and southern Iraq. They became some of the earliest Christians, and navigated life under the Persian and Islamic Arab Empires. Following the devastating Mongol sweep across Asia in the thirteenth century, the Assyrians were largely confined to the mountains of northern Mesopotamia and the plains that stretched out from them. When their bid for autonomy failed, the Assyrians of the Hakkâri mountains (in today’s south-east Turkey) were expelled from their highland redoubts. Along with the Kurdish tribes they conscripted, Turkish nationalists attempting to create an ethno-religiously pure Republic deported or killed every Christian they could find between 1914 and 1923, and murdered around three hundred thousand Assyrians.

The surviving Assyrians marched, starved and ravaged, towards uncertain futures across the region and beyond. Most ended up concentrated within Iraq, scattered across refugee camps and exposed to further depredation. Iraq celebrated its independence by massacring three thousand Assyrians in and around the village of Simele in 1933, an exhibition of how the state planned to treat the potentially disloyal. Crowds in Baghdad greeted the returning army by garlanding them with flowers and rose water.

But the violence of the early decades of the century left a permanent legacy. The Patriarch of the Chaldean Church, a Catholic offshoot of the Church of the East, and a bishop of the Syriac Orthodox Church in Iraq wrote to King Faisal, probably under duress, congratulating him on the “peace” yielded by the massacre. The Church of the East Patriarch, Mar Shimun, was exiled from Iraq in 1933.

Saddam let the Assyrians be Christians as long as they exchanged everything else about themselves for the privilege of worship. Assyrian civil organizations, media outlets, and clubs and societies were outlawed by the mid-seventies. The modern Assyrian language — the morphology of which is partly rooted in the Akkadian language of the ancient Assyrians — was restricted to the home. Ancient Assyrian figures were depicted as early Iraqi Arabs, undermining Assyrian claims to an indigenous, non-Arab ethnicity.

Catholic schools taught their pupils in Arabic rather than Assyrian; one of the men closest to Saddam was a Chaldean Catholic who Arabized his name from Mikhail Yuhanna to Tariq Aziz. When Saddam was still feted by America, he was handed the key to the city of Detroit after donating two hundred and fifty thousand dollars to a Chaldean Church (whose reverend had publicly congratulated the dictator on his ascent to power).

Jockeying for a piece of influence was a mainstay of life under Arabist totalitarianism — with the lid of tyranny lifted, preachers, bishops and imams pulled apart the strains of ethnicities and congregations. In 2003, in the run-up to the U.S. invasion, the influential Chaldean bishop Sarhad Jammo wrote a letter to Paul Bremer describing the grouping of Chaldeans with Assyrians — in fact ethnically indistinguishable save for sect — as “an injustice against our people” and demanded that they be recognized as a separate ethnic group, despite previous claims to the contrary.

Since 2003, Assyrians have been the targeted victims of the whole spectrum of atrocity. More than seventy churches across Iraq have been attacked or destroyed. Entire neighborhoods have been emptied of their residents following episodes of rape, murder, and intimidation deliberately fashioned to purge Iraq of Christianity. A pre-2003 population of around 1.2 million mainly ethnically Assyrian Christians in Iraq has dropped to four hundred thousand.

All of the poisonous movements in Iraqi politics conspired in June of 2014, when Mosul — Iraq’s second city — fell to ISIS. Mosul, a largely Sunni city that was historically a hub of mercantile comingling, had been plagued by the Sunni insurgency since the collapse of central authority in Iraq in 2003. Racketeers funded jihadi activity by theft and extortion; dozens of teachers, professors, and other educated people were killed or expelled; clergy were abducted and executed. Suicide bombers targeted administrative and government institutions. Three weeks after the capture of Mosul, the groundwork was laid for the declaration of an Islamic Caliphate.

Following the full withdrawal of US troops from Iraq in 2011, the expression of Baghdad’s insecurities towards Sunnis intensified. On paper, the Iraqi army in Mosul outnumbered the invading ISIS fighters by at least ten to one. But the largely Shi’a government forces were deeply resented by their charges, who perceived them as occupiers loyal to a remote and repressive state dedicated to sectarian persecution and marginalization.

The army in and around Mosul had extraordinary organizational and operational problems — poor training, dilapidated structures, failures of payment, “ghost” divisions, and corruption so endemic that soldiers would often bribe their superiors to abdicate duty. So what, and who, was the army fighting for? For Iraq’s political class and the Army officials tied to it, Mosul was not a city worth risking lives for; it fell with barely a shot fired. Souvenirs of the Iraq that its protectors had shed — badges, flags, uniforms — littered the ground. The jihadists treated themselves to a harvest of their desertion, reaping the Humvees, ordnance, tanks, weapons and bullets that America had endowed Iraq with, using them to carve their way into the state the machinery was purchased to defend.

A few weeks into the Islamic State’s occupation of Mosul, it tagged Christian property with “N” for Nassarah, the Quranic term for Christian, and Property of the Islamic State. Christians were told by decree on Friday, June 18th, that they had a day to decide whether to convert to Islam, live as Dhimmi, a subjugated rank afforded to some non-Muslims under a Caliphate, or flee. All but those who were too old or infirm to leave fled. They were robbed of all they owned, down to identification papers, pension books, and babies’ earrings. All forty-five Christian establishments in Mosul were closed, destroyed, or converted into an apparatus of the Islamic State.

The other historically Assyrian towns of the Nineveh Plains were all emptied of their hundred and fifty thousand inhabitants as militants sped along unobstructed. Thousands of Syriac manuscripts were burnt, and testaments to the Syriac Christian heritage were desecrated. The fourth-century Mor Behram monastery, built on the tomb of the children of the last pagan Assyrian king, was blown up in March. The Islamic State has also waged a campaign of destruction against the ancient material culture and heritage of northern Iraq, laying waste to the Assyrian cities of Nimrud, Dar-Sharrukin and the Seleucid city of Hatra. Just as they did a century ago, deracinated Assyrians roam Mesopotamia, seeking succor. Tens of thousands live on roadsides or in makeshift accommodations in the Kurdish-controlled cities of Arbil and Dohuk.

The Yezidis, concentrated in northern Iraq, adhere to an ancient Mesopotamian religion, influenced by Zoroastrianism, with Mithraic, Sufi, and Abrahamic elements, as well as sui generis teachings, superstitions, and legends. They believe that Xwede, the eternal God, created the universe, but then handed dominion over worldly affairs to a heptad of angels. Malek Tawus — an angel in the form of a peacock — is the most important: the mediator between humanity and Xwede. Their profound attachment to nature, a legacy of the original Mesopotamian faiths, extends to kissing trees, praying in the direction of the sun, and reverence for snakes and birds.

Yezidis do not prize a scripture — they have transmitted their communal mythologies, fused with memories of their persecutions, orally. (They probably only began to collate their fragments in response to the interest of nineteenth-century orientalists, although some Yezidis state that their original scriptures and language were destroyed by Muslims.) Their faith lives through memory, speech, and song, embodied in sanctuaries, shrines, and complex, insular modes of social organization. They accept no conversions, believing that they alone are descendants of Adam but not Eve. They are divided into castes endogamous within themselves. There are large Yezidi communities ins Ain Sifni and the Shekhan district of Nineveh, where they live alongside Assyrians, as well as in the Sinjar region in the northwest. The ribbed, fluted domes of their distinctive religious architecture punctuate the landscape.

Following the outbreak of ISIS across Nineveh, the Yezidis have been subjected to a campaign of genocide. They are not even recognized as ahl al-kitab, “people of the book” — those who follow scriptures deemed holy in Islam — a category that should extend to Christians, Jews, and Mandaeans. A fraudulent old calumny that construes Yezidis as devil worshippers has provided the religious justification for the Islamic State’s attempt to terminate their existence.

In the early hours of August 3rd, ISIS militants invaded Sinjar and surrounding villages, forcing tens of thousands of Yezidis to flee, mainly into the mountains, where they began to die from thirst, hunger, and heat exhaustion. Yezidi males old enough to have armpit hair were rounded up and executed or buried alive. Boys with hairless underarms were abducted, to be groomed into jihad. Young women and girls were abducted and sold into sexual slavery. Matthew Barber, a scholar of the Yezidi plight, has the names of at least forty-eight hundred girls involved in such abductions and around the same number of men killed. Some early eyewitness accounts of the enslavement of girls emerged on social media (along with many denials), but an article in the official Islamic State magazine Dabiq attempted to present a coherent Islamic explanation: In accordance with Sharia, the “polytheists” were rightfully distributed among the fighters “to help men avoid the sin of adultery.”

The only ground forces that provided a safe passage for beleaguered Yezidis around Sinjar were the Kurdish YPG militia of Syria. As the Iraqi army withdrew from the north, Kurdish militias quickly filled the vacuum. For a while, ISIS and the Kurds seemed to have an understanding: You take yours from Iraq, and we’ll take ours.

When ISIS began to advance on Assyrian and Yezidi towns — which had been occupied since 2003 by the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), who had disarmed the inhabitants — the Kurdish militias known as peshmerga (“those who confront death”) withdrew and fled back to areas securely held by the KRG. This betrayal continues to provoke a profound feeling of mistrust from Yezidis and Assyrians alike. The collaboration of some of their Arab and Kurdish Sunni neighbors with the Islamic State has compounded the sense among exiled Assyrians and Yezidis that they would find it very hard to go home, even if their towns were liberated.

The KDP (Kurdistan Democratic Party) — the dominant, tribally organized party within the KRG — has attempted to patronize the Yezidis into identifying as Kurds. In KDP propaganda, Yezidis are depicted as “original Kurds.” Yezidis act as a kind of living museum for the Kurdistan project, which has sought to implant deeper civilizational roots and narratives to render Kurdish territorial and national claims more robust. In exchange for KDP votes, the peshmerga promised to protect Yezidis, pressuring them to stay put until hours before the ISIS incursion — conveying no sense of imminent danger or of their own potential flight.

The Yezidis count seventy-two persecutions in their history: this latest could permanently disfigure their culture. There is little in the way of a coherent strategic understanding of how self-reliance could meaningfully sustain the Yezidi people.

ISIS has been deemed an unprecedented evil, but it represents the consolidation of disparate strains of violence and religious totalitarianism hatched across the region. Consolidation into a Caliphate has magnified and systematized the horror. It has certainly put into relief the abject failures of national organization in the Middle East. The lucrative ISIS trade in artifacts pilfered from archaeological sites consumes material history to fund the illusory manifestation of the original Islamic khilafah (Caliphate) and set in motion its eschatology. History becomes the very fuel by which it is burned.

Many of the more prominent former members of the Ba’ath party have put their skills and expertise, if not their ideology, to work in the formation and operation of the Islamic State. Their genocidal policy towards Shi’a Arabs is savagely regressive and steeped in sectarian mania, but is also a gamble of allegiance with echoes of the ethnic cleansing that created nation-states like Turkey and Serbia.

The flag of the Islamic State still flies over Mosul and much of Nineveh, and it tells its own visual story: primitive and stark, the warmly rounded letters — inviting in their almost dumbly handwritten thickness — spelling out the beginning of the shahada, the central Islamic creed. The circle beneath them, intended to represent the original seal of Muhammad, suggests a planet engulfed in the end of everything that came before him. A call to a pure beginning, their approach to statecraft is both shockingly regressive and consciously transgressive in relation to both modern Arab states and Islamist organizations.

Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi can be seen brushing his teeth with a miswak before his Mosul sermon, an affectation designed to hark back to the time of Mohammad — and yet his organization publishes a glossy four-hundred-page report annually, complete with infographics detailing the stylistic variety of their murders. The foreign fighters of ISIS have made a show of burning passports. Alongside propaganda and pageantry, ISIS moved with great speed in providing state functions — police, welfare, retirement homes, food distribution, law courts, street cleaning, electrical repairs — after the Caliphate was declared, making good on the pledge of a comprehensive Islamic entity while gains were still being made and the adrenaline of a prophetic vision was coursing.

Since the convulsions of summer 2014, the two most significant territories taken back from ISIS in Iraq have been Sinjar and Ramadi. Sinjar was re-taken in November of last year by Yezidi and Kurdish forces just as easily as it was abandoned by the peshmerga in the first place. The operation took two days, having been stalled for over a year, over questions of how to coordinate and divide both the operation and the spoils of it. The destroyed city is now occupied by a patchwork of competing militias and political interests. Mass graves of Yezidis slaughtered by the Islamic State are still being unearthed.

As for Ramadi, (strategically more important for the Iraqi government as it connects Baghdad to Syria and Jordan), some 80% of the city has been destroyed in the process of Iraqi security forces retaking it from ISIS, on top of damage and displacement sustained during a prior tussle for control in early 2014. While ISIS has been largely dislodged from the city, they will continue to pose a constant threat of infiltration and terrorism, impeding the repopulation and restoration of the city. Similar problems are likely to befall Fallujah, which the Iraqi army and affiliated militias are currently attempting to re-take from ISIS.

When it comes to Iraq, there is no status quo ante bellum. ISIS emerged out of the same fragmented and lawless Iraq that is now trying to combat it. The same failures that led to the rise of the Islamic State are plaguing attempts to defeat and supplant it. The heavily politicized nature of the Iraqi army, as well as the opportunistic presence of largely Shi’a militias beyond government command in anti-ISIS operations, is one deep problem. What will come after liberation is the next. It is almost inconceivable that the Iraqi government, riven across all lines and utterly beset by partisanship, corruption, greed and incompetence, can create a lasting sense of allegiance across its citizenry. Each side in Iraq is striving to position itself to emerge stronger after ISIS — but only to reap the greater spoils of their defeat.

At a rally calling for the protection of Iraqi minorities in London in September 2014, Iraq’s spurned inhabitants huddled to yell at the country that authored it. Chants modulated to include as many minority communities as had members present. As Mandaeans, Yezidis, Assyrians and others joined the crowd, they instructed those leading the chants to add their names to the roll call of peoples that needing saving. At the edge of the rally, just within earshot, a small group of Shi’a Arabs — a family of three and their friend — gathered around a bench in disappointment. The mother complained that the focus was on Christians. “What you’re saying happened to you has happened to us, too.”

These dispersed ambassadors of their former country were like strange relatives meeting at the funeral of a distant relative. Everyone was weighing their tears. They mourned not Iraq, but what it had taken from them.

Fund The Next Snapchat

It’s the one app everyone needs now.

What if there were an app that deleted every idiot picture, video, thought or series of emoji you were about to broadcast to the world before you put it out there for people to see? What if this app let you go ahead and tap out your feeble-minded statement and then rolled its virtual eyes at you before very visibly destroying it in front of you, possibly with some sort of bonfire GIF? Wouldn’t you feel better knowing that the dumb things you say and do and post and feel stupid about only seconds later were prevented from even existing in the first place? Now that Snapchat is making memories live on forever there is a space in the market for my STFU app. (I am also working on a patented YBFD filter which calls you a big fucking dummy every time you try to make a video of yourself shitting fireworks out of your mouth.) If you are interested in funding this please get in touch; the kids today are so stupid there’s no way they won’t fall for it, and we need to hurry up and strike while the imbecile VCs still have money to set on fire. Thank you.

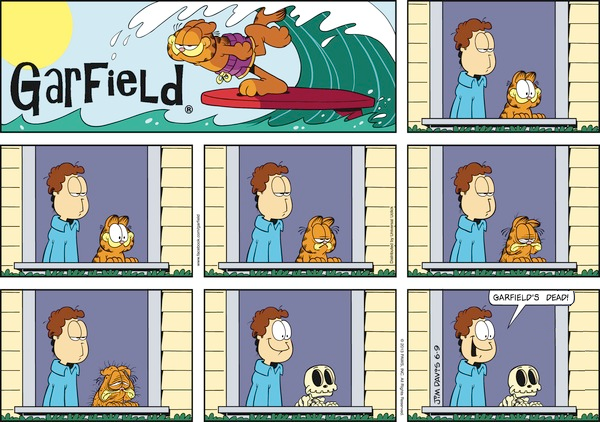

The Weird, Wonderful World of Subversive Garfield Spinoffs

It’s lasagna cats all the way down.

Even by the conventional standards of your local paper’s comics section, “Garfield” long ago achieved a level of mindless predictability that makes Charles Schulz look like Charlie Kaufman. Garfield’s brand of tame irascibility (hating Mondays and diets) has such broad appeal that he spawned his own merchandising empire, including several CGI-assisted films, a Saturday morning cartoon, and this inexplicable T-shirt.

Yet, that same tabby whose suction-cupped paws once graced the windows of family station wagons across the nation has also spawned a very odd subculture — one that draws from the worlds of avant-garde art, complex mathematics, and deliberate stupidity. Straddling the line between parody and homage, dozens of clever, hilarious, and downright bizarre “Garfield” spinoffs have popped up throughout the internet.

The most well-known variant is Garfield Minus Garfield, which removes the main character from published strips to unexpectedly dark results. Jon Arbuckle, Garfield’s owner and the frequent butt of his jokes, becomes the central figure and is revealed as an unhinged bachelor living on the fringes of society. As the website describes, “It is a journey deep into the mind of an isolated young everyman as he fights a losing battle against loneliness and depression in a quiet American suburb.”

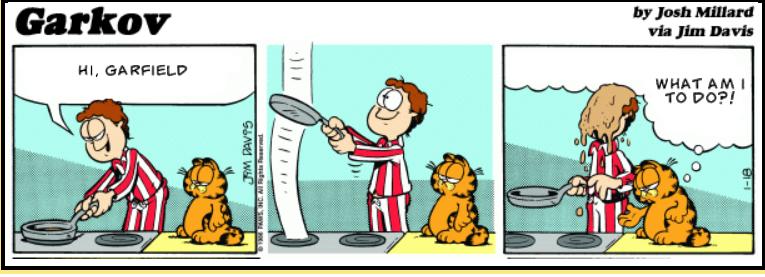

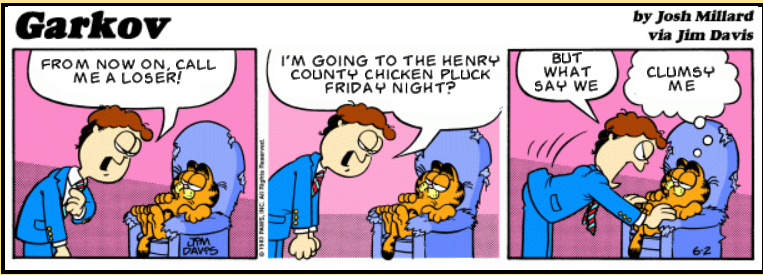

Garkov took that spirit of “Garfield” experimentation and added the next logical piece: a mathematical probabilistic model known as Markov’s chain. Essentially, it randomly combines dialogue from different “Garfield” strips, but in a way that verges on an odd coherence. Creator Josh Millard described via e-mail how the Markov chain worked off a generated list of pairs of key words mined from the strip, with the resulting comic “hopping from one source strip to another.”

“It’s like if you were whistling a song to yourself and switched melodies mid-stream to another song that had the same couple notes in a row right there,” explained Millard.

If the best way to describe Garfield Minus Garfield is existential, Garkov is its absurdist cousin. The site’s main page allows you to endlessly reload for new surrealistic combinations in search of the perfect Garkov comic. I’ve included some of my best results below, in which the familiar characters stalk Jon’s home spouting utter madness, as if in the throes of a crippling LSD trip:

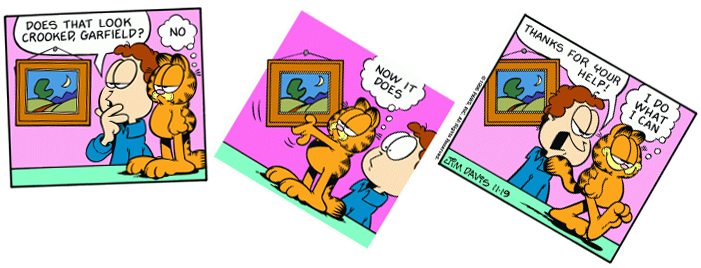

Many other randomizers have sprung up, including the addictive Random Garfield Generator, which allows you to load random panels from “Garfield” strips to create your own new strip. This iteration has chosen some particularly evocative panels (like the middle one pulled from this odd strip in which a diner waitress threatens suicide when Jon says his coffee is a little strong), and it also allows you to retain the ones you like while randomizing. Here are a few personal masterpieces:

Square Root of Minus Garfield sounds like a concept album from a prog-rock band, but it’s actually a self-described “webcomic devoted to parodies and mash-ups of the popular comic strip ‘Garfield.’” Variety and a prolific output are the site’s two best features, as it has updated daily with user-generated content since 2008. The submissions run the gamut in terms of scope and style: the visuals and/or dialogue may be altered and some comics are completely reimagined, whereas others are merely tweaked to highlight a disturbing subtext in the original. The titles range from low-brow (“Gimpfield,” in which Jon dresses up as Pulp Fiction’s infamous sex-slave) to post-modern (“The Physical Impossibility of Garfield in the Mind of Someone Living,” a physical strip suspended in a vitrine full of water).

As the site’s creator, David Morgan-Mar, explained to me via e-mail, “‘Garfield’ has evolved into a rigid format of layout, with fairly simple graphics, which makes it easy for many people to digitally alter to generate new parody strips. It’s the combination of familiarity, ripe parody material, and ease of making new submissions which has kept the reader submission rate high enough for us to publish a comic every day for the past eight years.”

There are a host of projects that have pivoted from Garfield Minus Garfield by choosing to substitute one of the main characters rather than completely remove them, with the choices often hinging on puns rather than contextual interplay. For example, there’s Garfield as Garfield, in which the lasagna-loving cat is replaced by former President James Garfield, who was tragically assassinated before his stance on lasagna could be ascertained:

Then there’s Minus Jon Plus Jon. As creator Chris Impink explains on the site, “In my own fevered dream amidst the Watchmen zeitgeist, it occurs to me that Jon Arbuckle’s existential woes have nothing on those of Jon Osterman, aka Dr. Manhattan.” Well, we were all thinking it. The resulting hybrid has the graceful symbiosis of a combination Pizza Hut and Taco Bell, as well as a very cool visual aesthetic:

All of this experimentation prompts one to nod one’s head before begging the question, “Um, why ‘Garfield’?”

Garkov creator Josh Millard explained, “The relative inanity of the original strip’s dialogue is a uniquely strong setup for weird/broken/scrambled non-sequitur text. I think that’s what works so well about so many ‘Garfield’ variations, really; it’s such a sterile, safe, drama- and menace-free strip that injecting *any* kind of Dada strangeness or emotional complexity into it makes it jump off the page a bit.”

In the spirit of jumping off the page, I’ll close with Lasagna Cat, a live-action video parody featuring a guy in a Garfield suit. These strange, uncomfortable clips are usually around 90 seconds long and follow a similar pattern: the actors faithfully recreate a “Garfield” strip to deadening effect (and the roaring approval of a studio audience), followed by a music montage set to a thematically relevant pop song. No other “Garfield” variant feels as aggressively juxtaposed to the source material as Lasagna Cat, and no other “Garfield” variant so effectively compromised the integrity of my sleep:

Ted Pillow writes.

A Poem by Colin Dodds

Winner Bars

The bars that poured

liquor down our throats for free

were driven out by bars

that overcharged us ruthlessly

And it’s terrible

But not much of a surprise

when you think of it

Thinking we were winning

we said winner takes all

And they took it

Colin Dodds is a poet, novelist and all-purpose writer whose work has appeared in more than 250 publications. He lives in Brooklyn, New York, with his wife and daughter. Read more at thecolindodds.com.

The Poetry Section is edited by Mark Bibbins.

Frankie Reyes, "Flor de Azalea"

Do you want to hear a story?

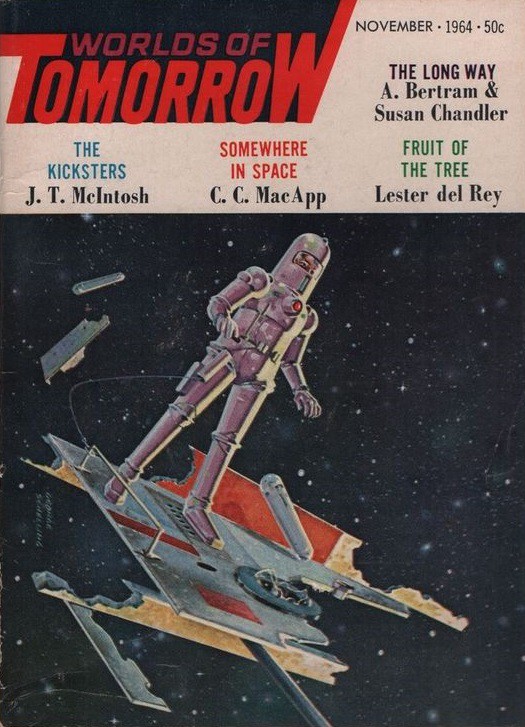

When I was a kid my dad would tell me about a science fiction story he read when he was younger called “The Carson Effect.” The premise was that a bunch of scientists discover that Earth is about to pass through some sort of toxic energy field or whatever and all human life will end. The elites of the establishment, wanting to forestall panic, decide not to tell anyone about it, but they spend their final days in acts of otherwise inexplicable generosity: the President resigns so that the Vice President can have the top job, color televisions are handed out freely, Tiffany’s sells all its diamonds for a dollar, etc. Come the day Earth goes through the poison cloud, nothing happens: the Carson effect of the title refers to Rachel Carson, and humanity has already polluted itself so severely that there’s no adverse impact any space garbage could have. The last line of the story, according to my dad, is, “But nobody gave anything back,” which is even more true and brilliant than the main idea. (I have never seen this story as it was actually written, but Google tells me it appeared in Worlds of Tomorrow in 1964. At this point reading it could only ruin the memory.)

If I were to write a science fiction story today — don’t worry, I promise you on all I hold dear that I will not — the idea would be that a savage species of extraterrestrial lands on the planet with plans of plunder and destruction but is so taken aback by the horror and savagery with which we treat ourselves that they immediately retreat in fear and disgust, warning all the other lifeforms to stay far away from the terrible place that they were lucky to escape. I mean, except for the aliens it might be a little too believable.

Anyway, I am just this morning learning about Frankie Reyes’

Boleros Valses y Mas. “I thought,” says Reyes, “about how I might capture the essence of [Latin American modernism] using my instrument of choice, the synthesizer. What came to mind was to cover some of the classic Latin American compositions that I grew up hearing around me and have grown to love as I’ve gotten older, most of them in the bolero style but a few in the waltz, son, and even mariachi style.” “Flor de Azalea,” below, is a little jarring initially if you are familiar with the standard version but, as it progresses, it transforms into something quite interesting that stands on its own. Enjoy.

New York City, July 5, 2016

★★ In the dim and humid morning, the remaining puddles were less drying up than spreading out, their damp edges merging into the ambient dampness. Over 18th Street the sky was still gray, but in the distance down Seventh Avenue the buildings popped out from the otherwise gloomy scene. Above them were blue gaps in the clouds. Fitfully and slowly the day cleared, till the sun was coming down everywhere, hot and direct, stinging like sweat in a paper cut. It began to seem as if those sullen clouds had been the day’s best feature. The sky and the light grew clearer and more brilliant, till the baking heat filled even the shade. It was impossible to resent the air conditioning. People moved slow-wittedly, getting in the way. On the crowded 1 train, a woman clutched the handrail along one side of the car with a straight arm, heaving backward to press her bulk against the center post as well, in simultaneous surrender and conquest.

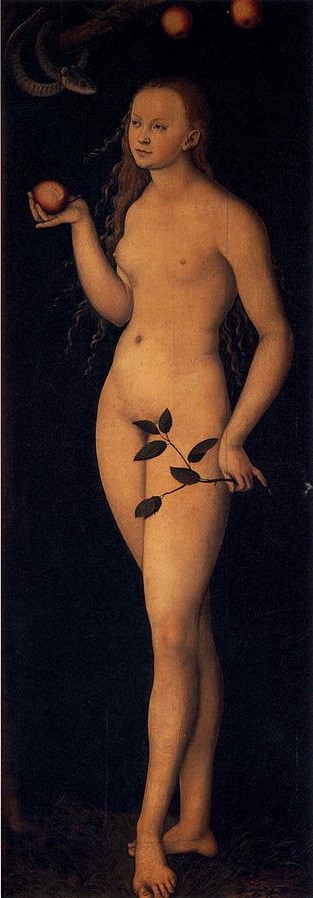

Welcome to the Summer of Eve

BY GOD, from the August issue of ‘For Adam Magazine’

Eden is so far gone, We have to go to your rib to make a suitable helpmeet. In case you’ve missed it, her name is Eve. She is today and beautiful, not in that otherworldly, Lilith-y way but in a whole land of Havilah, where there is gold, corner of The Garden scenario; a spirit moving over the waters; a mist from the earth. She is blonde, but only in European paintings. She might be tall, but who knows because We have nothing to compare her to, and there’s no such thing as shoes yet. (Don’t get Me started on what’s going to happen when there are. I’m sorry for all of you.) She can be sexy and composed even while naked but she’s also always naked and she isn’t aware of that at the moment. She has curves in ways you don’t have curves. She smells pretty, like the flowers of the garden, not in a whore-y way but just close enough that you feel like you’re being a little naughty, if you catch My meaning. As I said, she is from your rib. To understand her, you should think about what that means. Your rib is Eden at the beginning of the sixth day, sunny and slow, a throwback, a place where giving names to the animals passes for entertainment. And here she is, Woman, made for you by Me to enjoy and envision in whatever way you wish. Just make sure she doesn’t eat too much fruit, you’re not going to like her when she puts on the pounds.

I met Eve by the banks of the river Gihon (the same is it that compasseth the whole land of Ethiopia), in a booth toward the back. It’s good for a private chat because nobody goes there, there not being anyone else around but Me, and you, and now her. She wandered through the room like someone who had just been created moments ago, which was in fact the case. She skittered like a doe, which is the female version of the animal you are calling the skinny-legged head-horn horse. (We’re going to have to change that, but don’t get Me distracted right now.) I didn’t pay attention to what she was wearing, because, again, no clothes yet. She was naked, naked, naked. Not a big deal to Me, but boy is it gonna be a thing when all your sons grow up. She had her hair arranged artfully like in some Renaissance painting around those painfully blue eyes (the eyes are actually brown but by the time Western culture gets through with this story they are for sure going to be blue so let’s just stay with that). We sat in the corner. She looked at Me and smiled.

“I’m terrified of you,” she said. “You’re God.”

“Honey,” I said, “you have no idea.”

Wring Out Your Dead

A Chicago funeral director is championing a modern method of body disposal

Elizabeth Fama, a writer from Chicago, had been considering the different ways to dispose of a body after her mother-in-law, Lydia Cochrane, died. A traditional burial was off the table: Pumping her mother-in-law’s body with toxic embalming fluid on top of a pricey funeral didn’t seem right. Cremation was her next thought, but Fama didn’t like the idea of placing Cochrane’s body into a 1800℉ chamber, creating the same greenhouse gas emissions associated with climate change. She chose a third option, which she read about online, a process formally known as alkaline hydrolysis—most people call it flameless cremation.

Cochrane’s body was wrapped in a silk shroud and placed inside a machine that looks like a chrome-encased iron lung. A combination of water, lye (also known as sodium or potassium hydroxide), and low heat gently circulated over her body until it was dissolved into a coffee-with-cream-colored liquid. It cost Fama about the same as cremation, but left a fraction of the carbon footprint. “There’s no reason to say no to it, except that nobody knows about it,” Fama said.

The process of dissolving a body takes four to eight hours; families can be involved or not as they wish. For Fama’s family, that meant helping seal the machine and pressing the start button. “Even though pressing a start button seems like a small thing, it’s actually a big emotional moment,” she said. Instead of reducing the body to ashes with intense heat, alkaline hydrolysis uses a chemical reaction to digest the soft tissues into a sterile fluid that is later discharged to the local wastewater-treatment facility. Bones don’t dissolve because lye doesn’t have the same digestive reaction with calcium phosphate; instead, they are dried and pulverized into a fine powder that can be stored in an urn: not-quite ashes.

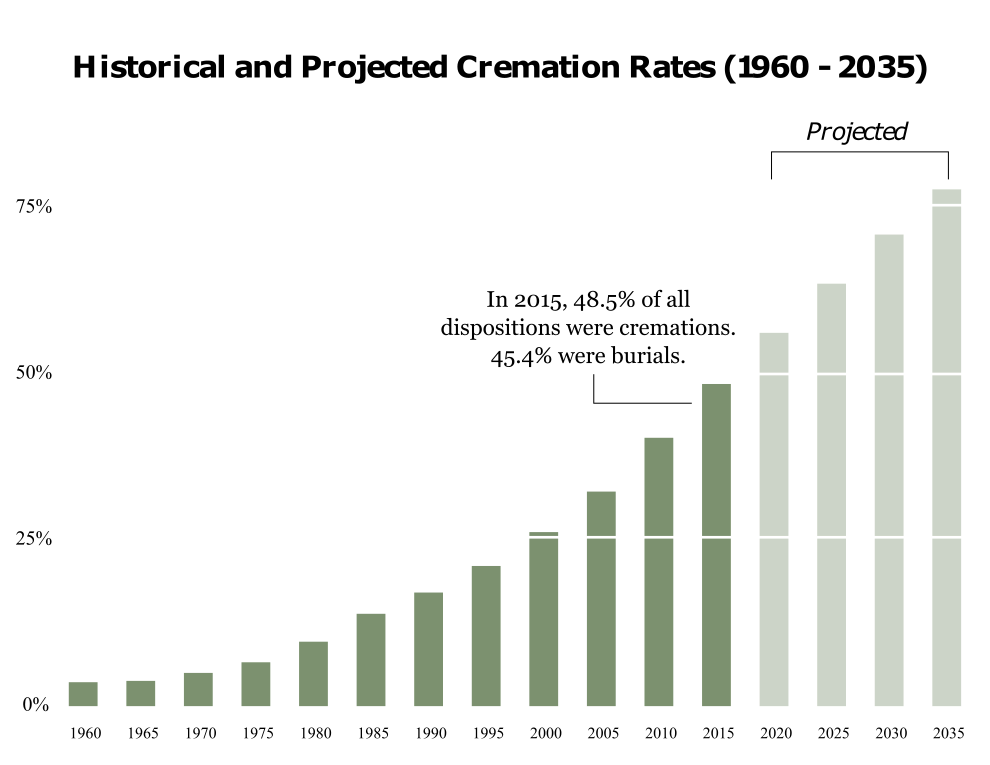

Over the last fifteen years, the rate of cremation has nearly doubled. And in 2015, for the first time ever, more people in the United States were cremated than buried. With more families forgoing expensive funerals in favor of cremations, flameless cremation stands to gain ground as a third, cheaper and more efficient option.

Ryan Cattoni, a funeral director based near Chicago, is the owner and operator of AquaGreen Dispositions, Illinois’ first and only flameless cremation provider—the same one that handled Lydia Cochrane’s service. It’s one of only five funeral homes in the U.S. that offers the service. Cattoni believes flameless cremation will disrupt the business of what we do with the dead. “It’s greener and more environmentally friendly since there are no air emissions in the process,” Cattoni explained, adding that his service uses 90 percent less energy and more than 75 percent less carbon output compared to traditional cremation.

Another advantage of flameless cremation is that elemental mercury from dental amalgam fillings isn’t vaporized, as in a traditional cremation. Also, there is no “bone commingling” — a side effect of traditional cremations, where it’s difficult to sweep out 100 percent of the ashes from awkwardly shaped cremation chambers. Lastly, the leftover fluid does not contain DNA or genetic material because the bonds in the nucleic acids are broken down.

If you drew a Venn Diagram of Cattoni’s clientele and Prius drivers, you’d expect a one hundred percent overlap. But Cattoni explained that the only thing his customers have in common is that they don’t like the idea of their body being buried or burned. None of them knew they had the option to be returned to the earth by water instead of fire before meeting Cattoni. “I think it’s just a little easier on the mind,” said Cattoni.

As a twenty-seven-year-old first-generation funeral director, Cattoni is an anomaly in his field. Cattoni only began to consider the profession after his grandfather died. He remembers how the funeral director, who handled the service, made it a littler easier and a lot less stressful for his family. “I figured if I could do that for other people, I’d truly be making a difference in somebody’s life,” said Cattoni, who enrolled in mortuary school after finishing high school.

Cattoni first learned about flameless cremation in 2010 while working to obtain his funeral director’s license. He came across an article in a trade journal describing the Mayo Clinic’s use of the process for their donated-body program. In 2012, when he was just twenty-three, he worked with state lawmakers in Illinois to pass legislation to legalize flameless cremation. That same year, after the legislation passed, Cattoni purchased a machine (which can run anywhere from $200,000 up to $450,000) and launched his own company. At first, business was slow. Cattoni’s mom helped with front office paperwork and his dad lent a hand during the procedures — all of which helped sell Elizabeth Fama on the idea. “It’s actually very comforting…to come in and see this family operation,” Fama recalled.

As word spread, so did demand for Cattoni’s service. People’s ears perked up whenever he mentioned flameless cremation. “It sparks an interest in people,” he said. Last year, AquaGreen Dispositions doubled its business. Now, families from Tennessee, Michigan, and Wisconsin are bringing their deceased to Illinois for a flameless cremation service.

In the next three decades, America’s sixty-five-and-over population is expected to double. The funeral industry will have to accommodate, and Cattoni is betting that more and more families will opt for his services. The last sea change of this scale came in 1963, when the Catholic Church lifted its prohibition against cremation. As environmental consciousness penetrates public dialogue, flameless cremation could be the way of the future. Fama compared Cattoni’s entrepreneurship to a young CEO in Silicon Valley. “He skipped right over the boring old mortician generation and went straight to what young morticians should be like right now,” Fama said.

Not everyone is on board with the new wave of body disposal. Flameless cremation is illegal in all but ten states (Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Kansas, Maine, Maryland, Minnesota, Oregon and Wyoming). In 2012, the New York State legislature voted on a bill to legalize it, but ran into opposition from the New York State Catholic Conference. Before the bill was defeated, the Conference wrote in a memo, “It is therefore essential that the body of a deceased person be treated with respect and reverence. Processes involving chemical digestion of human remains do not sufficiently respect this dignity.” Last week, a communications rep confirmed by email the organization maintains that position.

Even in places where it’s legal, details on flameless cremation are hard to come by. David Weber, a funeral director from Baltimore, Maryland, believes that there isn’t enough information out there to give an informed opinion on the process. “Many of us feel that there needs to be a little bit more research…we know what the impact is for cremation, but were not certain what the environmental impact might be for alkaline hydrolysis,” Weber said.

A public relations manager from the National Funeral Director’s Association said over email that the organization does not take a position on the procedure. But it’s hard to imagine they’d be excited about anything that would eat into the ever-shrinking number of profitable funerals. In 2014, the median cost of a funeral was around $7,000. Cattoni offers transportation of loved one from place to passing, two copies of the death certificate, the service itself, and an urn for $1,795.

The main obstacle Cattoni faces in pursuit of growing his business is misinformation. “Some common things people say is that the body is placed in a vat of acid,” said Cattoni. Which couldn’t be further from the truth—literally. (Remember, the process is formally called alkaline hydrolysis—an alkali is a base , the opposite of an acid.)

Late last month, several Canadian news outlets ran stories with headlines like, “Smiths Falls, Ont., funeral business dissolves the dead, pours them into town sewers.” The sensational article described the work of a funeral director named Dale Hilton from Ontario who specializes in flameless cremation. Coincidentally, Hilton’s business is also called AquaGreen Dispositions — the same as Cattoni’s. A lot of people, including me, emailed Cattoni, thinking he and Hilton were the same person. “I’m the original AquaGreen Dispositions and I guess that [Hilton] liked the name so much that he decided to use it in Canada too,” Cattoni said.

The future of flameless cremation depends on whether the public can be convinced that it’s a responsible thing to do. When Cattoni isn’t working, he’s talking to anyone who’ll listen. “I go and do seminars whether it’s for one person or 100 people. It doesn’t matter,” said Cattoni. “The funeral industry is a very slow changing industry, I will say that,” he added. For better or worse, Cattoni will be around to see it. When his own time comes, Cattoni said he’s “definitely” going flameless.

What a Pack of Cigarettes Costs, in Every State

The price of smoking in America in 2016.

Every summer since 2011 the Awl has released a report on the State of Cigarettes in America. As always, we called a random gas station or convenience store in each state’s most populous city and asked for the price of a pack of Marlboro Reds, colloquially known as “Cowboy Killers.” Kentucky reclaimed its 2013 title as the cheapest state, but if you want reliably cheap cigarettes, head to North Dakota — the only state to make the top five every year. New York remains the most expensive.

Thirteen people were unable to give prices over the phone, including a number of employees at the Midwestern chain Kum & Go, whom you would expect to be more chill. A woman in Kansas City said, “Honey, I don’t have time for this,” a man in Delaware gave several different price estimates before telling me I’d called a Quiznos, and someone in Salt Lake City said, “Nice try,” before hanging up on me. At one gas station in South Dakota a child answered the phone. He could estimate the price of a pack of Marlboro Special Blend but did not know about Marlboro Reds. When I asked how old he was he said, “Lemme go get my dad.”

I am the only person in the office who smokes — a source of great shame, which I blame on my mom playing too much Randy Travis when I was a toddler. Randy Travis is the smoker’s id, a man so determined to buy cigarettes he walked into a Tiger Mart naked, before crashing his Pontiac Firebird Trans Am in Tioga, Texas. If Marlboro Reds were a car they would be a Pontiac Firebird Trans Am.

47. Kentucky (last year $5.45): $5.19 = -5%

46. Tennessee ($5.70): $5.28 = -7%

45. North Dakota ($5.10): $5.32 = +4%

44. Hawaii ($8.02): $5.35 = -33%

43. Missouri ($5.64): $5.40 = -4%

42. Idaho ($5.61): $5.45 = -3%

41. Florida ($8.40): $5.57 = -33%

40. Mississippi ($5.75): $5.59 = -3%

39. Alabama ($5.97): $5.62 = -6%

38. North Carolina ($6.12): $5.81 = -5%

37. West Virginia ($5.52): $5.89 = +6%

36. Arkansas ($7.09): $5.94 = -16%

35. Ohio ($6.69): $6.01 = -10%

34. Oklahoma ($5.71): $6.04 = +6%

33. Indiana ($6.26): $6.16 = -2%

32. Wyoming ($5.45): $6.22 = +14%

31. Oregon ($6.06): $6.24 +3%

30. Colorado ($5.93): $6.31 = +6%

tied with Virginia ($4.98): $6.31 = +27%

29. South Carolina ($5.91): $6.34 = +7%

28. Georgia ($5.14): $6.44 = +25%

27. Delaware ($6.08): $6.60 = +8.5 %

26. Montana ($6.63): $6.70 = +1%

25. Utah ($7.12): $6.84 = -4%

24. New Hampshire ($6.44): $6.90 = +7%

23. Louisiana ($6.07): $6.92 = +14%

22. Maryland ($6.78): $7 = +3%

21. Nebraska ($6.32): $7.01 = +11%

20. South Dakota ($6.49): $7.09 = +9%

19. California ($7.81): $7.16 (-8%)

18. New Mexico ($7.01): $7.37 = +5%

with Nevada ($8.64): $7.57 = -12%

and Texas ($6.69): $7.57 = +13%

and Wisconsin ($8.06): $7.57 = -6%

17. Michigan ($6.64): $7.60 = +14

16. Maine ($7.47): $7.67 = +3%

15. Iowa ($6.18): $7.73 = +25%

14. Kansas ($7.02): $7.83 = +11%

13. Arizona ($7.75): $8.10 = +4.5%

12. Washington D.C. ($8.39): $8.15 = -3%

11. New Jersey ($8.06): $8.37 = -3%

10. Minnesota ($8.36): $9.07 = +8.5%

9. Pennsylvania ($7.04): $9.50 = +35%

8. Connecticut ($8.53): $9.65 = +13%

7. Washington ($9.22): $9.75 = +5.7%

6. Alaska ($13.50): $10 = -26%

5. Rhode Island ($9.13): $10 = 9.5

4. Vermont ($9.02): $10.43 = 16%

3. Massachusetts ($10.53): $10.67 = +1

2. Illinois ($13.25): $11.26 = -15%

1. New York ($13.50): $12.60 = –6.66% (!!!!!!!!!!!!!!)

Rebecca McCarthy is an Awl Summer Reporter and a bookseller.