A Poem by Jennifer K. Sweeney

bike shed will often show more results than “bike shed”

Whale song will often be louder than “whale song”

as flower girl runs faster into the field than “flower girl”

and star dust settles more thickly than “star dust.”

Fish stick will often know more of fish than “fish stick”

and beach glass will often know less of the sea than “beach glass.”

Draw fire away from its place, rain from coat, milk from man.

Let light in

that strangeness may be

reassembled by the breath

that a bike be a shelter that a shelter carry us off on slim wheels

that riding is a condition of leaving

that some fearsome thing always comes loose in a circular wind.

Unhemming the couple

one pauses to see the thing in its own delicate spiral,

this cannot be helped.

You with your sturdy distance, I with my mud shoes and water spicket,

how I want to part them now ecstatically the mud and the shoes

the table and the spoon, the air and the port

and zoom down the center aisle with you

shedding ourselves of bikes and stars and plans.

Jennifer K. Sweeney is the author of three poetry collections: Little Spells (New Issues Press, 2015), How to Live on Bread and Music, which received the James Laughlin Award, the Perugia Press Prize and a nomination for the Poets’ Prize, and Salt Memory.

The Poetry Section is edited by Mark Bibbins.

Little Scream, "Dark Dance"

Here’s some good news about America.

I have seen a great deal of despair of late on the confessional booths of our age about the sorry state in which the country finds itself, and I want to take a moment here as our nation’s resident optimist to make you all feel a little better about the world and your place in it: Everywhere is terrible, not just America. America is no more awful than anywhere else that has people in it, and proclaiming that it is makes you a proponent of the same kind of American exceptionalism that we rightly find repellent when it is done in the boostery I-love-guns-blonde-girls-with-big-tits-and-apple-pie routine that so many people confuse for patriotism. I want you to cheer up for a minute and consider this: It’s not just America that’s fucked, the whole species is fucked. America just does things louder. Human beings are horrible in every way and our end cannot come quickly enough, although it seems only fair that the Earth drags it out to ensure that we experience maximum suffering before our extinction. Now don’t you feel better? We’re all going together. I want you to remind yourself of that over the next week or so, when you’re really going to need it.

Anyway, here’s another track from the new Little Scream. The video is… something else, but if you are the kind of person who instinctively rolls eyes or [makes “jerking off” motion] at things that get a little, uh, artsy, just keep the sound on and go to another tab, the track is terrific. Enjoy.

New York City, July 12, 2016

★★★★★ A man trooped along toward the subway in a suit with his tie still undone, pacing himself against the threat of heat to come. A burning cigarette, evaporating washwater from the sidewalk, and the smell of a restaurant kitchen all took their places on the air. The temperature, though, never mounted beyond what was bearable. People were dressed for it; the breeze flowed over their clothes and kept moving. A nonsmoker could feel the itch for a cigarette break, just to get out into it, to stand out in the afternoon going by. The sun hit a drinking glass and stretched its shadow along the length of the table, throwing off a star of brightness at the near end. Fine clouds, unseen before, caught the setting sun and filled the featureless-seeming sky with a pink glow, intense and intensifying.

Selected Items from the 1988 Auction of Liberace's Estate And Their Catalog Descriptions

1. Liberace’s Nevada Driver’s License

“Of typical form, to include Liberace’s photograph and signature with the expiration date of 1988. $250–500”

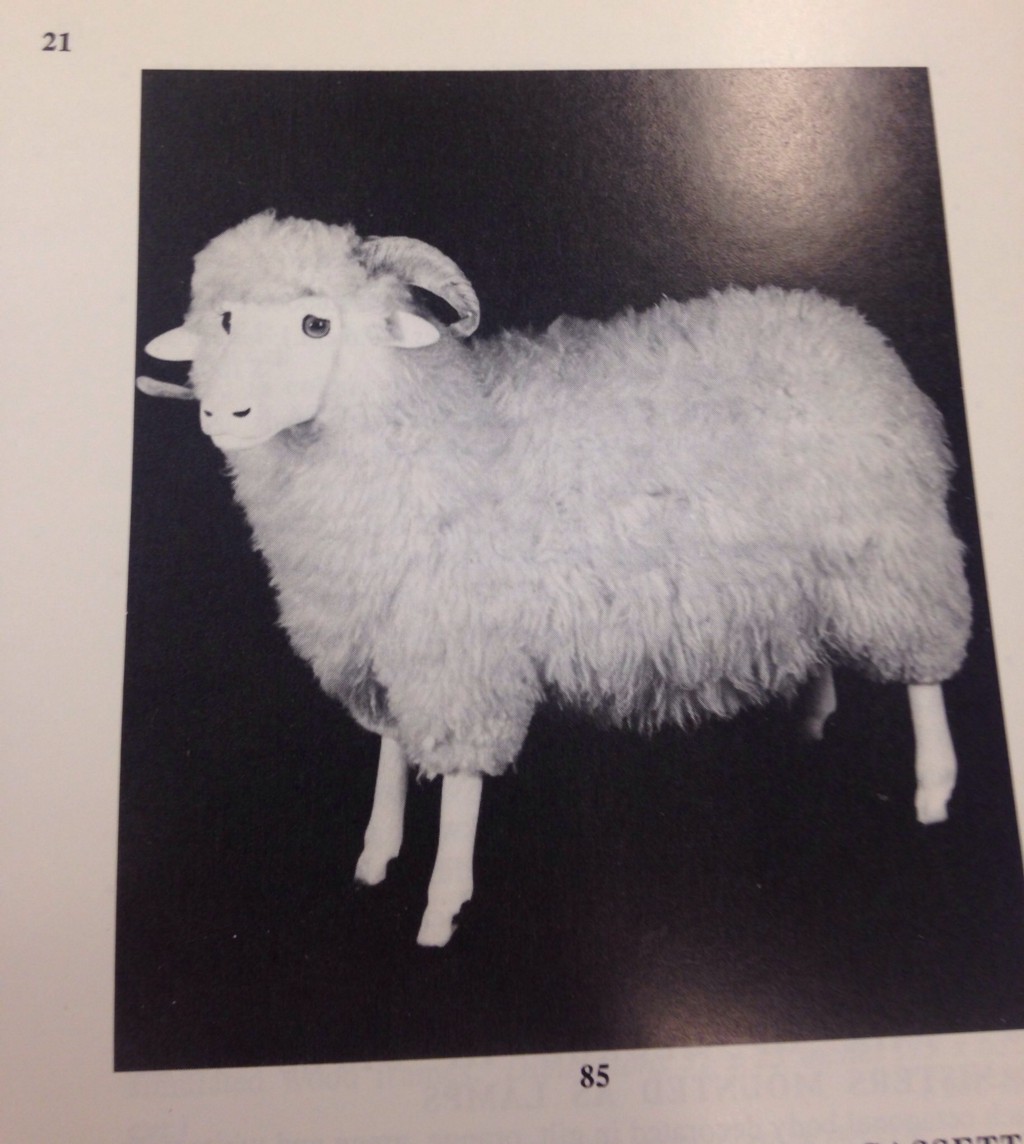

2. Pair of Large Contemporary Wool Figures of Sheep

“Each with curled composition horns, felt ears and face, (damage to one). Height 28 inches; length 29 inches. $500–750”

3. Three Gentleman’s Wristwatches

“An amusing personalized wristwatch, the circular multicolored dial depicting a caricature of Liberace at his piano, the letters of his hame indicating eight of the hours, in a stainless steel case attached to a black strap; another wristwatch, signed Pulsar, and a third wristwatch imitating a classic model of an important watch company. $10–100”

4. 14K Yellow Gold Poodle Pendant on Chain

“The 14K yellow gold poodle with extended paw, when the paw is pushed down the poodle’s head lifts and his eyes open to reveal two round rubies, suspended from a 25-inch chain of 14K yellow gold bar links. $500–750”

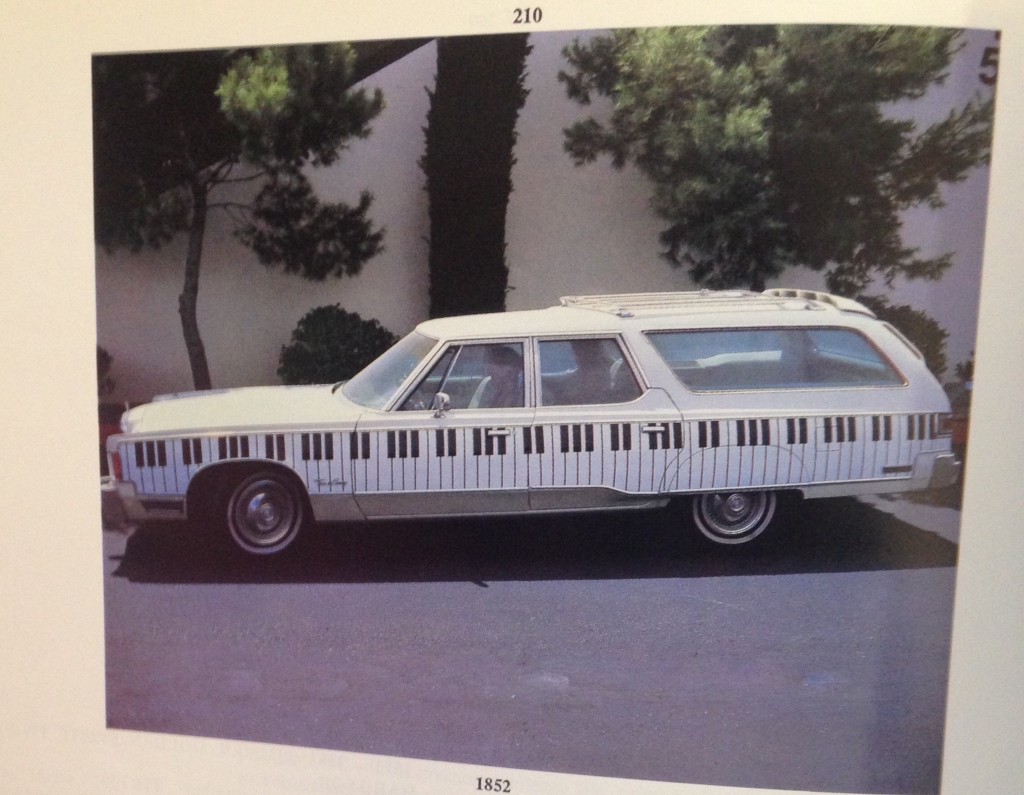

5. 1977 Chrysler Town and Country Station Wagon

“Nevada License number CRZ970, recorded milage 51,692, the cream body painted below the waistline with a continuous piano keyboard, cream interior. $2,000–3,000”

6. 14K Yellow Gold, Diamond, Ruby, Koala Bear Brooch

“The 14K yellow gold climbing koala bear accented by a round diamond, his eyes set with two small round rubies. $10–100”

7. Amusing 14K Yellow Gold, Citrine Cigarette Case

“The rectangular, hinged 14K yellow gold box decorated with a rectangular-cut citrine supporting a 14K yellow gold candelabra with red enamel flames. $250–500”

8. Pair of Massive Chinese Ceramic Temple Lions

“Each crouching on a rectangular stepped plinth with head turned and gaping mouth framed by flowing ribbons and hogged mane, each body glazed brown with thick green highlights. $500–750”

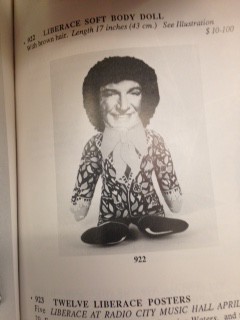

9. Liberace Soft Body Doll

“With brown hair. Length 17 inches. $10–100”

10. Contemporary Framed Lithograph: “Friends”

“Printed in vivid greens, blues, browns, and yellows, with four seated dogs, green and fabric mats (lucite cracked). $10–100”

11. Cowhide Evening Jacket

“The jacket with gold and cream bugle bead lapel and cuffs, with detachable ruffled bib, together with brown trousers and matching cowhide shoes. $500–750”

12. Two Framed Photographs of Dogs

“Depicting a Yorkshire terrier and a Laso Apso, each with giltwood frame, together with two embroidered linen pillows, the first of rectangular form embroidered with the inscription Happiness is being a mother, the other inscribed Happiness is being a grandmother, each with floral lace ruffled borders.”

13. Rhinestone Crown

“Typically formed with open panels each with a fleur-de-lis motif. $100–250”

Rebecca McCarthy is an Awl Summer Reporter and a bookseller.

Soundscan Surprises, Week Ending 7/7

Back-catalog sales numbers of note from Nielsen SoundScan.

The definition of “back catalog” is: “at least 18 months old, have fallen below No. 100 on the Billboard 200 and do not have an active single on our radio.”

Prince’s records are still selling like crazy—he holds positions 1, 3, 17, 19, 46, 93, and technically also 75 because of the Batman soundtrack. May it never stop. But the real reason we’re here today is to discuss THE PIANO GUYS???????? WHO ARE THE PIANO GUYS? DID YOU KNOW ABOUT THE PIANO GUYS? HOW DID I NOT KNOW ABOUT THE PIANO GUYS???? Usually when I don’t know about someone on the back catalog list it’s because they’re either a Christian or metal band, but according to iTunes The Piano Guys are a “21st century multimedia collective,” so will someone please submit a profile of them to notes@theawl as soon as humanly possible? K great thanks.

18. CLAPTON*ERIC ICON 2,982 copies

55. CROWDER NEON STEEPLE 1,917 copies

103. ARCTIC MONKEYS AM 1,435 copies

137. PIANO GUYS PIANO GUYS 1,292 copies

161. BEYONCE DANGEROUSLY IN LOVE 1,155 copies

164. THREE DAYS GRACE ONE-X 1,136 copies

165. THREE DOG NIGHT MILLENNIUM COLLECTION 1,135 copies

166. SKILLET AWAKE 1,132 copies

189. EN VOGUE FUNKY DIVAS 1,063 copies

(Previously.)

Girl Talk

Transgender voice therapy and what it means to sound like a woman

Lauren Lee had dressed with care that morning. She wore a sheer blue-and-white polka-dot blouse, blue jeans, and a thin gold chain around her neck. Her fingernails were tipped with red polish. A pair of wire-rimmed glasses and a delicate dusting of blue eyeshadow completed the look.

But she was more concerned at the moment with how she sounded. As an iPad listened from a nearby table, she read aloud a series of sentences from a sheet of paper before her. A white line streaked erratically across the screen with every syllable — skyward when her voice squeaked, back down when it deepened — as she tried to keep the pitch of her voice between 185 and 215 hertz.

When she failed, she closed her eyes, massaged her cheeks, and tried again. “My laptop needs to be charged,” she said, slowly and deliberately, the lines once more spiking up and down like a child’s drawing of a mountain range.

Lee had been coming to this dimly lit room, which barely fit three chairs, a table, and a motivational poster of children declaring, “We are communicating! We speak from our hearts! We understand!” twice a week for a year and a half. Shannon Hughes, a speech pathologist at the University of Connecticut’s Speech and Hearing Clinic, was her teacher. Hughes recorded Lee’s frequency from the iPad during every session, which began with vocal glides — oral glissandos that made Lee sound like an amateur opera singer — before transitioning to scripted sentences and improvised conversations. Throughout, Lee’s goal was to stay in her pitch range.

By the end of her training, the clinic promised, Lee — who presented as a man for fifty-three years before undergoing facial feminization surgery in September — would sound like a woman.

Vocal training is a step in gender transition that often goes unnoticed and unreported. Vanity Fair’s eleven-thousand-word account last June of Caitlyn Jenner’s transition from burly Olympian to sultry socialite contained seven mentions of her breasts, six of hormone therapy, three of her tracheal shave — also known as an Adam’s apple reduction — and zero of vocal training. Even the setting of voice therapy is more muted than the gleaming plastic surgeons’ offices in Boston and San Francisco where reassignment surgery often takes place. The Speech and Hearing clinic at UConn, where Lee went, is in a low, fluorescent-lit brick building in the rural town of Storrs, Connecticut, population eleven thousand.

Yet for many transgender people, sounding like their true gender is just as crucial to the transition process — and at times, just as complicated — as looking the part. What does it mean to sound like a woman, or to speak like a man?

Technically, the answer is simple: Male voices are usually deeper, produced by longer, thicker vocal cords that vibrate at frequencies between 85 and 180 hertz. Female voices are typically higher-pitched and usually fall between 165 and 255 hertz. But pitch is not the only determinant of a voice’s apparent masculinity or femininity. Resonance, which is how full a voice sounds, matters too — Lee’s falsetto, for instance, may be properly high-pitched, but it was often thin and unconvincing. According to Hughes, men also tend to speak in a more staccato style, whereas women are more fluid; men are louder, and women make more eye contact. Women use more hand movements than men, and they have a greater tendency to use so-called “tag words” at the end of sentences, right? These generalizations and stereotypes may be nothing more than that, but they play a significant role in shaping others’ perception of one’s voice.

Most transgender people who seek vocal therapy are males transitioning to female; unlike testosterone therapy, estrogen therapy does not affect the thickness of the vocal cords. Nothing short of surgery will shorten someone’s vocal cords — which is where the UConn clinic and others like it come in, teaching their clients techniques to sound more feminine.

The field of transgender voice therapy is still relatively new. Early literature emerged fifty years ago, but the field has gained momentum over the last two decades. Currently, there are about three dozen different locations across the country offering transgender voice therapy. One of the earliest such clinics opened in the mid-eighties, when Richard Adler, then a professor of speech and hearing science at Emory University, started a private practice at the request of Atlanta’s transgender population. The UConn clinic began offering transgender services five years ago, after an annual internal evaluation revealed that many transgender students on campus wanted such a program.

The stakes of sounding like one’s presented gender are high: Nineteen percent of transgender people have been refused medical care as a result of their gender identity, according to the National Center for Transgender Equality, and one percent have even been physically assaulted in emergency rooms. Twenty-one percent don’t tell their medical providers that they are transgender — an omission that cannot be sustained if their voice does not match their appearance. “If one day you’re in a car accident, and you’re lying in a hospital gurney and you look like a young woman but sound like a man, you’ll get discriminated against,” Lee said.

There are also smaller daily battles. Once, Lee said, a cashier called her “sir” when she ordered a snack at a restaurant. “I was wearing a skirt and a blouse, and they said, ‘Thank you, sir,’” she said. “That’s just kind of like a little punch in the gut when that happens.”

Lee was born in 1962 in Cleveland, Ohio as Terrence Lee, Terry for short. She knew before her fourth birthday that something didn’t feel right. When she was three, she was sent to her grandmother’s house during the birth of her younger sister. Lee hid in her grandmother’s closet and draped herself with earrings and necklaces. “I was afraid to death that my father would come through the door and catch me,” she said. “I knew that it was quote unquote wrong, that I shouldn’t be doing that because I’m a boy.”

Lee was especially close to her female cousin down the street, and always wanted to be doing whatever she was doing. At school, Lee enviously watched as girls played with dolls on the other side of the classroom, while she sat with the boys and halfheartedly joined sports teams at her father’s request. In college at Kent State, forced to live in an all-men’s dorm for two years, she said she was “horrified.” But she never told anyone how she felt. She hoped that one day she would wake up and her discomfort would be gone, that she would finally be happy in her body as a boy.

Just before college, Lee had begun piloting airplanes, following a childhood passion. In 1986, she joined the airline industry, and became a captain the following year. Her vow of silence solidified: Aviation was, and still is, a male-dominated industry. Back then, women held just .02 percent of pilot certificates; today, the number is just six percent. Lee saw her beloved profession as another reason to keep her long-held silence.

In 2013, Lee’s mother fell and broke her hip, then suffered a series of strokes. Lee returned to Cleveland from Providence, Rhode Island, where she had moved in the meantime, and split her time between the hospital and her childhood home. One day, she began flipping through old photo albums. “I could not find a single photo where I was smiling,” she said.

That October, Lee decided to see a gender therapist — not with the goal of transitioning, but as she put it, to find a way to “deal with it.” In spring 2014, she started hormone therapy and began attending sessions at the UConn speech clinic, about an hour from her home in West Greenwich, Rhode Island. At work, though, she still presented as man: A photo from June 2014 shows Lee in a pressed captain’s uniform, with closely cropped gray hair, wearing white iPod earphones and frowning into the camera.

As the months passed, Lee realized that the middle ground she’d been trying to navigate for the past fifty-three years would no longer suffice. She had three choices, as she put it: “transition, go crazy, or die.” In January 2015, she notified United Airlines of her gender transition. Eight months later, a plastic surgeon in Boston cut back Lee’s jawbone, inserted cheek implants, and peeled back her forehead to sand down the strong brow bone that is characteristic of male faces. The procedure lasted eight-and-a-half hours.

When Lee returned to work in November, the stern, lock-jawed Captain Terry from the photo was gone. In his place was Captain Lauren, the first transgender captain who was not immediately grounded by the Federal Aviation Administration following a gender transition. This January, the FAA announced it will no longer classify transgender pilots as having a disorder, paving the way for countless other transgender pilots.

As much as Lee focused on her pitch, as the old urban legend goes, over ninety percent of communication is nonverbal. So Hughes spent just as time training Lee to hold her hands close to her body, as women do, or to nod to show that she’s listening, as she did helping Lee adjust her pitch.

But this training strikes at the heart of debates about the definition of femininity, which have engrossed feminists for decades. Some of the cues the clinic teaches, like the proper form for hand gesturing, are more or less inoffensive. But others, like the directive to imbue sentences with a singsong quality, have generated more pause, for what some say is their role in reinforcing sexist gender stereotypes. Wendy Chase, the clinic’s director, raised this in an interview with the Associated Press: “There is tremendous irony in the fact that we use information based on stereotype to make people feel better about themselves,” Chase said. “But that’s what we do.”

Indeed, many of the techniques that the clinic’s speech therapists teach their transgender clients to help them pass as more feminine are behaviors that have been used to label women as unassertive, insecure, or silly. Journalist Jessica Grose, while hosting a podcast for Slate, said she often received emails from listeners criticizing her female “upspeak” and “vocal fry” — ending sentences on a higher pitch or drawing out the ends of sentences, respectively. Listeners said they made her sound unauthoritative. In 2014, Fortune urged female professionals to “avoid squeak” if they wanted to be taken seriously. And when Hughes instructed Lee to begin sentences with “um” as a tool for self-calibration, Lee’s responses couldn’t help but take on the apparent uncertainty that has been used to caricature women’s speech.

In other words, the clinic uses gender stereotypes to train a group that is already, by definition pushing back on stereotypes of what it means to belong to a certain gender. When asked about this tension, Chase laughed. “Because society has already determined how it feels about gender identity, and the mannerisms that go along with that, by buying into some of those stereotypes, someone can feel more comfortable not being misgendered,” she said. “We don’t use those stereotypes because we agree with them. We use them because the research supports that people who can pass more easily by using some of these characteristics are more satisfied.”

Questions about embodying stereotypes about women have continued to plague Caitlyn Jenner, whom many have hailed as the harbinger of mainstream acceptance of the transgender community. After Jenner made her tightly-corseted appearance in Vanity Fair, transgender actress Laverne Cox praised Jenner’s courage but gently reminded fans that descriptions of both Jenner’s and Cox’s own beauty revolve around their ability “in certain lighting, at certain angles…[to] embody certain cisnormative beauty standards.” PBS news anchor Gwen Ifill was more blunt, tweeting, “Let me get this right. Asserting one’s femininity means posing in a low cut swimsuit. Ok. Got it.”

Several months later, after Jenner told BuzzFeed that the hardest part of being a woman is “figuring out what to wear,” actress Rose McGowan wrote an open letter telling Jenner that women are “more than the stereotypes foisted upon us by people like you.” And after Jenner told Diane Sawyer last April that her brain “is much more female than it is male,” feminist scholar and documentary filmmaker Elinor Burkett penned a blistering opinion piece in the New York Times blasting Jenner for suggesting that gender is simply a matter of neurological processes. “By defining womanhood the way he did,” Burkett wrote, “Mr. Jenner and the many advocates for transgender rights who take a similar tack…undermine almost a century of hard-fought arguments that the very definition of female is a social construct that has subordinated us.”

Lee, for her part, is unfazed by this. For her, there is no tension between her learned behavior and her gender nonconformity, because she has known her true gender identity her entire life; the clinic’s training was not so much about adopting new mannerisms as it was about allowing herself to embrace long-suppressed ones. “I used to catch myself doing female-type things, like standing with my legs crossed and my hip out, or stand with my hand on my hip. My father would nudge me and say, ‘Boys don’t do that,’” she said. “A very hard part now is stopping censoring myself and allowing that stuff to happen.”

After Lee finished reading the sentences she moved on to her improvisation exercises, which challenged her to keep her voice in range without focusing on it exclusively. Hughes read off a number of prompts — list three steps you should take before a job interview, describe an airport farewell scene — and Lee made up answers. “You see two people standing outside. One of them gets in the car, slams the door, and speeds away. The other person is still standing there crying. What just happened?”

“Um, it was probably an argument that led to a breakup of some kind.” Lee paused. The intentional “ums” mixed with unintentional ones as she became flustered. “I don’t know. A business deal gone bad? A romance gone bad?” The words tumbled out of her mouth, getting thin and reedy before plummeting into a fuller, but much lower, tenor. She cut herself off.

Hughes changed tactics. “Why don’t you give me three sentences you might say to your passengers?” she asked. “Ladies and gentlemen, the fasten seatbelt sign has been turned on,” Lee recited. “Please return to your seats and make sure your seatbelts are securely fastened.” Lee’s pitch stabilized into a smooth, confident alto. “Look how nice that is,” Hughes said. “Let’s practice that one again, because you’re going to use that a lot.”

During Lee’s twenty-eight years as Captain Terry, she often purposely deepened her already gravelly tenor to sound as authoritative as possible, and to reaffirm, either to herself or to her passengers, her own maleness. She dropped her voice to demonstrate, and the sound was startling in its deep, rich tones and the ease with which it emerged from her throat.

Now, even though Lee is Captain Lauren, her passengers do not see her new blonde bob or meticulously painted red fingernails. They don’t see how she holds her hands in close to her body. They only hear her voice over the intercom, and when she announces that the plane’s landing into Chicago will be delayed by half an hour, she wants to sound unmistakably female.

For this reason, Lee’s target range was actually quite a bit higher than the frequency that would acceptably pass as female. If she accomplished it, her voice would actually be twenty hertz higher than Hughes’.

In March 2015, CNN published an article about trailblazing female airline captains. While the number of female pilots has grown slowly but steadily over the decades, the number of female captains — pilots who are in charge of the rest of the on-flight crew — remains at an astonishingly low at four hundred and fifty worldwide. Lee came across the article recently and sent it to one of her friends who is one of the four-fifty, to congratulate her on being among the elite. “She texted back, ‘Lauren, welcome to the club,’” Lee said. “But I don’t really feel how much I belong to that club. Nobody ever questioned if I could be a pilot, if I was smart enough, strong enough.”

Lee recognizes that as fraught with challenges as her life has been, it has not, until recently, been fraught with specifically female ones. But now, she is content, even eager, to embrace society’s feminine norms, the good and the bad — whether that means painting her nails bright red or speaking in a higher pitch, as she discovers what it means to live as a woman, collecting the social experiences whose absence Burkett and other critics say make transgender women incapable of understanding true womanhood. After all, cisgender women aren’t born with their “female” experiences either; they accumulate them, through years and years of making their way through society while being seen as women.

“I’m not looking to set the world on fire,” Lee said. “I know I’m never going to be an attractive woman, or a desirable woman; I started at an age when it’s just not going to happen. I just want to live my life without being questioned. If people perceive me as a woman, period, that’s what I need. That’s all I need.”

In April, after two years of vocal training, Lee went under the knife once more, this time for the vocal surgery she had been hoping to avoid by attending the clinic. The training wasn’t enough, and she didn’t want any more anxiety about her voice. Lee once described being transgender as being stuck in a room with a very loud machine grinding away in the background. Certain things, like flying, distracted her from the noise temporarily, but it was always there.

As she began her gender transition, the noise began to diminish: a little bit with hormone therapy, a little bit more with her surgery. Voice therapy helped quiet it further, vocal surgery even more. Maybe one day it will be gone. And now in its place, there is a new noise, one she’s making for herself — just a little higher than before.

Vivian Wang is a student at Yale University.

Francis and the Lights, "Friends" feat. Bon Iver & Kanye West

Normally Balk puts something really obscure and ethereal in this space, but today it’s me and I don’t know anything obscure so I’m going to put the song we’ve all been listening to for the last five days here because I’m a bit behind so I’m still just catching up on completing my loops. I was out of the country for a week and I have no clue what Pokemon Go is besides a Vox headline generator; I refuse to find out more, and you can’t make me. I’m going to stay here on this side of the line with all the bad news, dancing presidents, and heat waves. Isn’t it amazing how desperate we are to be distracted by moving pixels?

I like this song because it’s a perfect length, just a few seconds north of three minutes. It has Justin Vernon, whose other stage name I don’t like to pronounce out loud, and a wistful Kanye West, who I can’t quite tell whether or not his actual vocals are on the track or if his person just appears in the music video. The video is calmly strange and sort of soothing in its own way. At one point Francis and Justin Vernon do some light choreography without breaking a sweat, and what’s better than grown men moving in sync with each other with little to no affect? The camera pans out as the men pose and we see Kanye doing exactly what you think he’d do on the set of a music video, just standing under a light box in the corner, thumbing his nose.

Francis and Justin/Bon (along with many others) will perform at the Eaux Claires music festival in August.

New York City, July 11, 2016

★★★★ Bright flies hopped on a dog turd on the sidewalk of 71st Street, a sidewalk strewn so thickly with dog turds it seemed to have been conscientiously done to prepare for the morning commute. The temperature was always on its way to being something else, edging between warmth and chill, the air alternately stale and fresh. Whatever it was, the air conditioning was the wrong solution. By afternoon the sunny side of the street was a refuge. The light came sideways and bluish, diffused through little puffs of cloud that were pressed together in rows, rows pressed together in a sheet. The sun got lower and lower till the cloud sheet was gray and the bits of cloud above and below it were white. The whole structure came apart then, into brilliant flakes or coins of silver and gold scattered across the west. They shone for a long time, fading slowly while the colors of light around them warped to orange and lemon and a final deep magenta.

The World's Dumbest, Greatest Adventure

Mongol Rally participants drive 10,000 miles across Europe and Asia without a clue

Every summer, hundreds of thrill-seekers flock to Goodwood Motor Circuit, a historic race track in the south of England. They gather, dressed in themeless costumes, to participate in what some refer to as the greatest adventure in the world. No training or planning is required or even recommended, so participants are as young as eighteen and have been as old as seventy. Their ranks include penniless students, successful business types, and some that are “in between jobs.” But for a month and half, they all share a common goal: get to Mongolia. They’re participating in the Mongol Rally, a 10,000-mile journey in comically unreliable cars from the UK to a city in eastern Siberia.

There are no prizes for being first across the finish line. Instead, teams are encouraged to one-up each other to see who can complete the Rally under the toughest conditions. Anyone can drive a quarter of the way around the world in a Range Rover; it takes a certain industriousness to do it in a vehicle that would qualify for Cash for Clunkers. The Mongol Rally’s website tells teams:

“You must bring the shittest rolling turd of a car you can find. Use a car you swapped for a bag of crisps.”

Think of the Mongol Rally as the equivalent of trying to run a marathon in house slippers while shotgunning beers at every checkpoint. It starts out funny and gets exponentially more ridiculous and dangerous the further along you get.

The Mongol Rally is “organized” (these quotes will make sense later) by a UK-based outfit known as The Adventurists. For the past twelve years, The Adventurists have brought together people from all across the world to participate in various adventures that are guaranteed to make your friends laugh and your mom cry. Next week, on July 17th, more than 900 people will gather at Goodwood to set off on the largest ever Mongol Rally. It’ll take teams about five weeks to travel a distance similar to the drive from New York to Los Angeles and back — twice. Most teams just hope to finish. Many won’t. “If you’re guaranteed success, it’s pretty predictable,” said Dan Wedgwood, the managing director of The Adventurists. “It’s…more fun not knowing if you’re going to make it,”

There are three rules to the Mongol Rally, which have mostly stayed the same since its inception:

Rule 1) If the car looks like it would survive a trek across seven different time zones and multiple deserts, it’s probably not allowed. Specifically, cars must have an engine smaller than 1.2 liters (for reference: most modern Mini Coopers have an engine size between 1.4 and 1.6 liters).

Rule 2) Beyond occasionally posting in a Facebook group, the Adventurists offer no help. They tell where you the Rally starts and where it ends. Teams are on their own to plan a route, obtain visas, and decide what to bring.

Rule 3) Each team has to raise a £1,000 for charity. Half goes to a charity of the team’s choice and the other half supports the Rally’s official charity, The Cool Earth Foundation.

The Adventurists and the Mongol Rally date back to 2001, when Tom Morgan, the original founder, drove a Fiat 126 from the Czech Republic to the stupidest place he could think of (Mongolia). A few years later, in 2004, Morgan convinced a handful of friends to partake in the inaugural Rally. Since then, Morgan and the rest of The Adventurists have made a living out of organizing different escapades where the only thing at stake is bragging rights.

The Adventurists organize six other events, including a Rickshaw Run across India, and something called an Ice Run, where participants motor across 400 miles of frozen river in Siberia on Soviet-era motorcycles during the dead of winter. And then there’s the Ngalawa Cup, where teams try to sail a boat that’s been hollowed out of a mango tree through the waters of Zanzibar. But the Mongol Rally has always been the organization’s bread and butter, and it’s never been more popular.

“I thought it’d be funny for awhile and then I would probably die,” said Dan Wedgwood, who first got involved with The Adventurists in 2005. Fresh out of university, Wedgwood was toiling away at an office job that he found miserably boring. He had plans to quit the job and take a reverse Trans-Siberian Railway trip until a friend told him, “Stop being a pussy. You’ve already got a really bad car. Why don’t you just drive to Mongolia in my cousin’s Rally.” So Wedgwood ditched his train plans and signed up. That year’s Rally saw 43 teams start and only 18 finish. “We were all just idiots,” he said. Wedgwood brought a few tools for repairs — among them, a screwdriver that he later learned was made for fixing sunglasses.

After completing his first Rally, Wedgwood helped Tom Morgan turn The Adventurists into a money making enterprise. Sort of. At first, most of the participants were, like Morgan and Wedgwood, broke college graduates. It wasn’t clear how the organization would survive without enough participants who could pay an entrance fee. “We weren’t very clever business people…It was kind of like let’s go run some adventures and if we can pay ourselves in wages that’d be marvelous,” said Wedgwood.

In 2006, 143 teams signed up for the Rally — triple the number from the previous year. The Adventurists, who couldn’t afford an advertising budget, attribute the uptick to word of mouth and free press from curious journalists. Twelve years later, that’s still how most people discover the Rally.

Joe Rittenhouse was one of the last four contestants in a competition where the object was to keep a hand on a statue of George Washington the longest. A $2,000 cash prize was at stake. “I tried to negotiate that if we all let go, we’d split the prize four ways,” recalled Rittenhouse, a twenty-six-year-old from Collegeville, Pennsylvania. But one contestant wouldn’t budge. The hold-out told Rittenhouse that he needed the money for that year’s Mongol Rally. That was four years ago, and he’s been looking for someone to join him on the Rally ever since. This year, Rittenhouse convinced his girlfriend and a few others to register as “Team Keystone.”

Like most participants, Rittenhouse is woefully unprepared. His entire knowledge of car maintenance is limited to a 20-minute crash course his cousin, a mechanic, gave him one afternoon a few weeks before the Rally. “He showed me where the belt goes, and where the fuel line is, and the three things that make an engine run, and that was about it,” Rittenhouse said with the casual hubris of someone who doesn’t yet know he’s going to be in trouble. When asked why he wanted to participate in an event where finishing wasn’t guaranteed, Rittenhouse said he wanted to know how he’d handle himself if he was in the middle of nowhere and something went wrong. “If I don’t make it, I’m going to do the rally again. It’s that simple. It’s a test I’m determined to complete,” said Rittenhouse, who will be riding along in a Nissan Micra and a Hyundai Atos.

Elsewhere, Rittenhouse could rightfully be scolded for his lack of preparation. But the Mongol Rally discourages planning. In fact, foolhardiness is rewarded. One of the prizes The Adventurists give out is for the team that’s “Least Likely To Make It.” In 2014, that went to a participant who brought a Ferrari 456 to the Rally (they made an exception to the 1.2 liter rule). He got to Georgia before turning around.

The Rally is intentionally designed to maximize setbacks, mechanical or otherwise; teams are forced to embrace their helplessness. And so the teams that do finish tend to be the ones that are most cooperative and courteous with border guards, policemen, and local mechanics.

But not everyone appreciates the fly-by-the-seat-of-your-pants mentality that The Adventurists peddle. Jin Choi, from Edmonton, Alberta, had an unforgettable time in last year’s Rally, but has no intentions of participating in another Adventurists-organized event. “They offer no help…It’s literally their motto to go on an unsupervised adventure,” said Choi, a 24-year old graduate student. He didn’t understand why The Adventurists charged an entrance fee. For £650, teams receive t-shirts and a few parties at certain checkpoints during the Rally; the rest is exchanged for memories.

As the Rally has grown in popularity, it’s become more diverse. About a quarter of the participants are women, the average age is in the late-twenties, and last year’s Rally had participants from twenty-five different countries. Despite its growing popularity, Wedgwood dismisses the notion that the Rally has been watered down. He believes, if anything, it’s gotten more dangerous, especially as more teams forgo a ferry across the Caspian Sea in favor of driving south through Iran.

Last year, eight participants ended up in the hospital during the course of the Rally. In 2010, one was killed in a car wreck. Wedgwood says he doesn’t pressure anyone to participate. Instead, he recommends they watch a YouTube clip of the Rally. “If it make you shit your pants, don’t bother.”

As for the future of the Rally, Wedgwood said he’d rather cancel it before making a change that goes against the Rally’s original ethos. “If we just started changing stuff for the sake of it…we’d just become any other bullshit travel company that’s just trying to design stuff for people who will buy something for the maximum amount of money,” Wedgwood said.

This year, The Adventurists are embedding videographers with teams. The goal is to capture enough footage for a possible television show. There’s been some interest, but pickup is far from guaranteed. Wedgwood wouldn’t have it any other way. For him, it’s more fun not knowing if he’s going to make it.

Owen Phillips will participate in this year’s rally. His mother isn’t thrilled.

Polly Asked

A chat with Heather Havrilesky and some advice column highlights.

Heather Havrilesky’s How to Be a Person in the World: Ask Polly’s Guide Through the Paradoxes of Modern Life is out today, and over at The Hairpin Miranda Popkey chats with her about a whole bunch of stuff.

“Reading her,” writes Popkey,” is not unlike listening to your best friend finally reveal, four drinks in, what she really thinks of your boyfriend,” and that may be the best description I’ve seen so far of why the column resonates as widely as it does. (And also why some people can’t handle Heather’s truth; not everyone wants to hear it.) Here are a few of my favorite columns from Heather’s original run here at The Awl:

Should I Cut My Abusive Mother Out of My Life Forever?

I Think My New Boyfriend Might Be a Horrible Control Freak

Why Am I Deathly Afraid of Success?

How Do I Make My Boyfriend Listen?

Only Black Men Like Me, But I Don’t Like Black Men

My Boyfriend Thinks I’m Clingy and This Terrifies Me

How Do I Find True Love And Stop Dating Half-Assed Men?

My Boyfriend Won’t Stop Raging About My Sexual History

How Do I Find True Love And Stop Dating Half-Assed Men?

That should do you while you’re waiting for your book to arrive. And there’s plenty more here.