7 Ways You Change As A Writer After Working On The Internet

Images: Courtesy of Blogger

It’s hard to write about the internet and not reference Mark Zuckerberg or BuzzFeed, Kanye West’s Twitter, The Dancing Baby, YTMND, Gawker, The Social Network, Jack Dorsey’s beard, “She doesn’t have the range,” the tiny room at Instagram HQ where everyone ’grams themselves, Crying Jordan, the shruggie, I Can Haz Cheezburger and Lolcats, AOL Buddy Lists, Periscope, WebMD, net neutrality, or Y2K.

Because everywhere you look, the internet is a wondrous cornucopia of the least charitable opinions of all the worst people you’ve never encountered. Every link you click will throw you further down the well, and every favorite or poke or like or heart will artificially spike your heart rate, only to have it crash when you accidentally type your own name in the search box. For every projected emotion and live viewing experience, there will be be a tweet you can find in the Library of Congress that will make you smile, but not chuckle. Consider that the internet is a terrible topic for artists and novelists because it enables even lunatics to feel like they’re onto something. Forget fame and fortune—you only have to gain over ten thousand followers to experience the meaninglessness of your own life. Look down at all the bots and trolls and feel your perspective drain away from you as your body grows slack and your mind goes blank.

The internet is a sclerotic, tumorous entity, a mass of ever-expanding cells whose rapid conversion into ads so targeted they show you ads for things you tweeted about yesterday you just can’t escape. Every generation that logs on to the internet goes through three stages: lost, angry, dismayed. Most people who come to the internet to forge a career in writing—be they fresh NYU grads or your dad’s retired friend with a blog about career advice—come to the internet thinking they have something unique to say. But in the first few posts, you realize, you’re exhausted by all the self-promotion, and there is no time to sit around and fiddle with your SquareSpace page. Most of your time will be spent sending invoices you receive checks for three months later. And so, though you might still recall the days when you had proper Vitamin D levels from regular sun exposure, you will have become An Internet Person, the second one of your tweets goes viral. Here are all the ways things will change for you after that:

You Will Come To Terms With The Fact That You Do Not Look Anything Like Your Profile Picture

Come on.

You Will Feel Alone

Because you are.

Taye Diggs Will Follow You On Twitter

Join the club.

You Will Stop Watching The News Just To See What It’s Like Not To Know

It’s admittedly kind of fun.

You Will Give In And Delete Your Tweets

What were you saving them for?

You Will Develop An Offline Employment Fantasy

Don’t you think you could be good at running a diner? I do.

You Will Give In And Click

Sorry but you will.

Quiz: Reaction to Donald Trump's Most Recent News Conference or Description of the Waters of Rio de...

Quiz: Reaction to Donald Trump’s Most Recent News Conference or Description of the Waters of Rio de Janeiro Where Olympic Athletes Will Compete?

This is a tough one!

“Despite the government’s promises seven years ago to stem the waste that fouls Rio’s expansive Guanabara Bay and the city’s fabled ocean beaches, officials acknowledge that their efforts… have fallen far short. In fact, environmentalists and scientists say Rio’s waters are much more contaminated than previously thought,” Andrew Jacobs reported in the New York Times. Meanwhile, the Republican nominee for the presidency held a press conference in which he “[encouraged] Russian espionage against the United States.” Are the terms below characterizations of the press conference or depictions of what lurks within Brazilian beaches?

- “veritable petri dish of pathogens”

2. “putrid stew”

3. “drug-resistant ‘superbacteria”’

4. “human crap”

5. “disease-causing”

6. “pure sludge”

7. “raw sewage”

8. “household garbage”

9. “chemical waste”

10. “oil and muck”

11. “It’s disgusting.”

12. “much more contaminated than previously thought”

13. “Keep your mouth closed.”

Answers: They’re all about the waters in Rio, but admit it, there were a few where you were pretty sure they were about Trump.

Porcelain, Lacquer, Hardwood

Kyoungjin Bae and the secret life of eighteenth-century Chinese furniture

Remember Mo Pareles from a few Lab Reports back? Her wife Nicole has a brother named Jon, and Jon has a partner named Kyoungjin Bae. She, like the rest of them, is a genius; I thought you might like to meet her.

Bae got her PhD in History from Columbia in May this year. She moved to the US for grad school, from South Korea where she majored in history and minored in education at Yonsei University in Seoul. She began grad school there, specializing in early modern European history. But trans-regional history (think: interdisciplinary international relations of the past) drew her in, and she decided to specialize. Bae went on to a doctorate in the international-global history track at Columbia, where she became interested in the cross-cultural history of early modern China and Britain.

She’s the kind of historian who is interested most by objects, although professionals call it material culture. Bae is currently working on a co-authored article about the financial system of the imperial palace workshops during the Qing dynasty (the last imperial dynasty of China, in power approximately 1614–1912). Her dissertation is about the history of Chinese furniture produced and exported for the European market in the eighteenth century. It’s called “Joints of Utility, Crafts of Knowledge: the Material Culture of the Sino-British Furniture Trade during the Long Eighteenth Century.”

In the beginning of the eighteenth century, furniture made in Canton (present-day Guangzhou), China, became a big hit export to Europe. Chinese exports were no new thing, of course — porcelain had been manufactured for European export since the 16th century — but this furniture was crafted out of hardwoods from the Indian Ocean and produced in European designs. It was often, Bae told me when we spoke recently, “indistinguishable from its Western counterparts.”

Previous scholars studying Chinese export objects, Bae said, have mostly “focused on European reception through the lens of exoticism.” Chinese products in European culture have often interested historians for their Chineseness, their difference to the material surroundings within which they found themselves.

By focusing on export furniture, Bae wants to “complicate our understanding of Sino-European exchanges.” If a dresser or a chair came from one place, and doesn’t look like it did, but undoubtedly lived a material life in a different place, what can that object tell us about the world that made it? (I’m speaking for Bae here; historians don’t put things so crudely.) This puts me strangely in mind of ersatz goods, the late twentieth-century stereotype of Chinese-manufactured products that imitate American plastics or fashion. The objecthood of this eighteenth-century furniture was nothing like the “knockoff” products of today. The material nature of the goods is different; it insists that we pay attention to its historical truth.

Bae follows the stories of Chinese export furniture “from its origins in the intra-Asian timber trade to its requisition and manufacture in Canton to its reception and use in Britain, highlighting how this process linked the disparate spheres of commerce, decorative arts, and natural science.” These objects turned local practice into global products; they drew processes and histories and other things into their orbit. Object histories show connections the way that a diagram of the solar system shows planetary routes that are invisible in the night sky.

Bae argues that export furniture can be interpreted as a transnational Eurasian object that “embodied cross-cultural knowledge of craft and nature and engendered new ideas of utility and sociability in both China and Britain.” History is made out of ordinary things more often than it is upended by extraordinary events: studying material culture grants us an audience with a bygone “normal” that is forever lost to those who only study revolutions.

Bae wants to figure out how to “incorporate the unspoken, unwritten bodily aspects of historical experiences into the study of history.” How have the body and material things “co-produced distinctive cultural patterns in the past”? For example: how, say, did craftspeople “use their own bodies and external materials — tools, ingredients, and workshop environments — to make things?” And why did people in the past “sit, sleep, and organize their desks and wardrobes in the ways they did?”

These kinds of questions raise procedural challenges of their own, giving rise to disciplinary challenges for researchers like Bae. To answer them, a historian must “connect divergent methods and perspectives from history, art history, anthropology, ergonomics, and STS [Science, Technology, and Society].” It’s important to Bae that she do this kind of study in a trans-cultural context. The dissertation was about Sino-European interactions, but in the future she wants to look at Sino-Korean exchanges, too.

Nowadays, we are now connected to each other in a way that feels barely related to space, or place. In Bae’s words, “the everyday life of ordinary people in one country is directly or indirectly connected to that of people in other countries.” Technology makes us especially aware of these connections, and that awareness grows in intensity every day. Bae believes we need to find “a deeper degree of mutual understanding,” to protect and develop certain “socio-cultural values that we as human beings can all respect and cherish.”

Kyoungjin Bae has a great “affinity for objects,” she told me, that has been “deeply woven” into the way she does history and research. She goes to see them at auctions, private galleries, museum warehouses, galleries — and she feels that an audience with objects is a privilege and a luxury. “What more could I aspire to in order to realize my childhood dream to be with objects?” she said. She deserves it all; the objects deserve her, too. Call me a sucker for a historian with a political conscience, but I find Bae’s dedication to old chairs and tables in the service of a new emotional understanding of globalization extremely moving.

Josephine Livingstone is an academic and writer in New York.

Christopher Tignor, "The Will and the Waiting"

What are we waiting for?

If I said something like, “We are all just waiting for the corpse flower to bloom,” you would roll your eyes and say, “Yes, Alex, we get it, everything is terrible and each day we pass through a series of sorrows and anything we do that brings joy is simply an illusion we allow ourselves to believe because otherwise we would be forced to confront just how empty and meaningless our sorry little lives are, and that is too painful for us to bear. Only you, among the many millions of us, truly understand how futile and absurd our brief transition from nothingness to nothingness is. We all really appreciate the way you’ve taken it on yourself to remind us at every chance you get that we’re going to die and in the meantime everything we’re doing is wholly without value. Who knows what might happen if you took a day off from telling us how pointless the things we do really are? Thanks so much for being the voice of cold, hard reality that we clearly need. You’re really woke about existence, you fucking jack-off.” And I would say, “No, it’s not a metaphor, I was talking about the flower at the Botanical Garden in the Bronx,” before bursting into tears and running away because you hurt my feelings so bad. I don’t do this for me, you know. God, why do I even bother? You’re so mean.

Anyway, you don’t deserve it, but here’s a track from Christopher Tignor’s forthcoming Along A Vanishing Plane. Tignor is “a violinist, composer and programmer who has developed custom software that allows him to perform grand drone compositions solo, as demonstrated in this video for ‘The Will and the Waiting.’ This is footage of him recording the version of the song that appears on the album in one take, no overdubs.” It’s very pretty and the perfect soundtrack for whatever you are in anticipation of, be it the blooming of a flower, or death, which comes for us all. Enjoy.

New York City, July 25, 2016

★ The stuffy elevator ride led down to streets full of a general and sourceless reek of garbage. Faces were grim and sagging. The four-year-old declared almost immediately that his legs were tired on the walk to camp. On the ledge outside the office window, a fly hunkered down on a thick lump of bird dropping. The afternoon smell clinging to the air on Fifth Avenue was not trash but sweat. Downtown the sky was white with glare and uptown gray was gathering. The gray closed in; people put up umbrellas; thunder boomed. People initially scattered but the storm came on without real cruelty or haste. For a while the sky stayed light, and the sun even broke through. Then darkness settled, with lightning and a long roll of thunder, and a real rain shone on the streets. Pedestrians headed to doorways, not desperately but as if it had just occurred to them to stop there. The rain kept intensifying, building to sodden fury. More lightning and thunder came in a sharp one-two, with the force and clarity of a storm in the open country. The different tints of headlights—yellowish, bluish, purplish—floated in the rain and splash above the pavement. What it had lacked in initial power the storm made up for in stubbornness, forcing the work day to drag on and on, as the big orange and yellow blobs on the phone’s radar map slowly gave way to big dark green blobs. When the rain finally slackened, the subway platform was crowded with people who’d waited out the worst, now trapped in damp miasma together. The daylight returned as an uncanny glow in the west, swelling in lurid yet indefinite colors.

The Story of a Name

Why are you proud of your family?

When I was a teenager I told my father I felt distant from everyone in my family. “It’s not that I don’t love you,” I said. “I just don’t feel like I’m a part of things, but I also don’t mind.”

“I think that’s ok,” he said. “I think more people feel that way than care to admit it.” The fact that he didn’t say it hurt his feelings is one of the most loving gestures anyone has ever made on my behalf.

I just got around to Awl pal Sarah Miller’s essay about her father and his father and the questions of meaning that swirl around our concepts of family and identity, and if you have not yet read it I strongly urge you to do so, it’s terrific. And I say this as someone who, if told this morning that he was going to read an essay about the questions of meaning that swirl around our concepts of family and identity, would have made the “jerking off” motion so hard and for such a prolonged duration that he would have shattered his scaphoid, lunate, triquetrum and pisiform bones beyond repair. And yet here I am, urging you to read it. Life sometimes still surprises.

How To Read More Books Now That You're Old

It’s okay: I used to be afraid too. Approaching a book made me squirmy. This is because in fourth grade I’d fallen behind in one of those Little House books and Mrs. Shill sent me home for spring break with make-up reading homework. I might appreciate the Little House books now, but at the time I loathed every last Ingalls girl. Their world of fiddle music and farm animals was the antithesis of what mattered to me at the time, which was pretty much the Rolling Stones and nothing else.

Because of my Little House punishment, I developed a Pavlovian response to the prospect of reading a book: panic. It was four years before I discovered that reading books can be a pleasurable voluntary activity: in eighth grade, a friend introduced me to Up and Down with the Rolling Stones, a memoir by Keith Richards’s former drug supplier. I loved every lurid page, and lost myself trying to figure out the salacious meaning of “His top lop protruded.” (Now I see that the o is next to the i on a keyboard, and “lop” is a typo.) You’re not going to like this, but that book changed my life.

I’m no longer afraid of books, although I never start reading one before I check to see how many pages it is. This is because I’m a member of the clean plate club when it comes to finishing a book. I still feel lousy about not finishing The Good Earth, and that was a couple of decades ago. Not finishing a book means that every minute you put into reading it until you quit was a colossal waste of your time. You’re too old for this now. You should finish what you start. Here’s how.

Go to your bookshelves and pick a book that you’ve never read — Ulysses, say. Look at the number on the last page of text, not including back matter; my Modern Library edition ends on page 783. Now see which page the narrative actually starts on: page 3. How nice for you: this is an easy calculation, as you can subtract 3 from 783 and get 780, a clean multiple of five, which is the number of pages you must commit to reading per day. (If the book had started on page 5, on your first day you could have guiltlessly read to page 8: you’re working your way up to the hard stuff.) Keep up with your five-a-day habit, and you will have read Ulysses in only 156 days. Believe me when I tell you that reading Ulysses will not be a waste of your time, which is not the same as saying that I’ve read it.

With a really excellent book, you’ll find after a few days that you will achieve liftoff and soar past the five-a-day requirement. You might even find yourself going for seven pages a day. Or maybe you’ll forgo counting the pages entirely once you’re sure you’re in flight. This happens for me with just about any book about artists in New York at midcentury, and maybe it will happen for you with that anvil Ulysses.

Once you’re done with Ulysses, you can add it to the list of books you’ve read this year. Note: You cannot include children’s books on this list, even long and laborious ones reminiscent of the Little House books such as Little Women, which I read last year (441 pages at five pages a day) because my daughter was reading it and I wanted to show my solidarity. If you include kids’ books on your list, you leave the system open to exploitation: what’s next, Hop on Pop? Hop on Pop is a great book, but come on. Children’s books go on children’s lists. Aside: My daughter’s list won’t include Little Women, as she wisely bailed after chapter 27. (She’s allowed to quit because she’s a kid. You’re not.)

Another way to commit to a book: read it aloud to someone. My husband owns a midcentury British spy novel called Miss Turquoise that I read out loud to him in five-page chunks whenever we go to bed at the same time and one of us remembers that we’re supposed to be reading it. (If you go the read-aloud-buddy route, never let your buddy do the reading: then you can’t put the book on your list.) Consider selecting a book that has been turned into a movie; watching the movie immediately after finishing the book is your reward, unless the movie is bad, in which case I apologize for suggesting it. Bonus: The film hopefully shellacs the story into your head so that if someone asks you what the book was about, you will have had a second opportunity to go over its plot points — that’s twice the chance for retention. (Again, you’re not young anymore.)

Now that you’re no longer abandoning books willy-nilly, it’s time to set clear goals for yourself — twenty-six books a year, say, meaning one every other week. Yes, it’s fine to reach for slim books if it’s November and you’re in danger of missing your target. I recommend The Birds, Camille Paglia’s assessment for the British Film Institute (I did 86 pages over three days concluding on December 31, 2015), directly followed by the Hitchcock marvel. Don’t press your luck, though. One year I’d read only twenty-five books by December 31 and had to borrow a slip of a Jamaica Kincaid novel from the bookstore where I was working at the time. I settled into the couch to read and was seized with some sort of sickness that put me booklessly in bed by around nine p.m., Mrs. Shill’s laughter ringing in my ears.

Nell Beram is a former Atlantic Monthly staff editor and coauthor of Yoko Ono: Collector of Skies (Abrams, 2013). Her writing has appeared at Salon and Slate and in The Threepenny Review, V magazine, and elsewhere.

Where There Is Harmony, May We Bring Dischord

Silence is a dangerous sound.

Finally, some good news, from the folks at Stereogum:

Dischord Records, the great DC punk label, has just posted its entire archive on Bandcamp, which means we can now stream every Dischord record for free without being signed up to Apple Music or Spotify or one of those. It also means we can buy digital copies of all of these albums for exceedingly reasonable prices.

Soundscan Surprises, Week Ending 7/21

Back-catalog sales numbers of note from Nielsen SoundScan.

The definition of “back catalog” is: “at least 18 months old, have fallen below No. 100 on the Billboard 200 and do not have an active single on our radio.”

It is a truth universally acknowledged that people don’t buy very many old records in the dead of July, but when they do, it’s like Remember The ’90s up in here. Take one step forward and two steps back with me, and marvel. Related: Green Day’s Dookie was the first compact disc I ever bought. My first cassingle, however, was SWV’s “Weak.” I do not know who purchased it for me. Crash makes me think of summer camp and my high school friend’s older brother who was a DMB obsessive and lined his bedroom walls with egg-carton foam for… some acoustic purpose or other. Sup, Allen.

A few formatting quibbles: Matthews Dave, comma band? And wasn’t it called The Chronic? Nielsen Soundscan, u crazy! Normally I would make a fuss about the apostrophe in the Destiny’s Child album, but I’ll let it go on a technicality: those songs own.

2. MATTHEWS*DAVE BAND CRASH 6,252 copies

45. BACKSTREET BOYS HITS CHAPTER ONE 1,922 copies

48. NSYNC GREATEST HITS 1,883 copies

60. DR. DRE CHRONIC 1,712 copies

87. DESTINY’S CHILD #1’S 1,478 copies

91. NIRVANA UNPLUGGED IN NEW YORK 1,452 copies

97. GREEN DAY DOOKIE 1,409 copies

134. LINKIN PARK HYBRID THEORY 1,219 copies

150. PEARL JAM TEN 1,132 copies

63. RAGE AGAINST THE MACHINE RAGE AGAINST THE MACHINE 1,083 copies

200. WU TANG CLAN ENTER THE WU TANG (36 CHAMBERS) 974 copies

(Previously.)

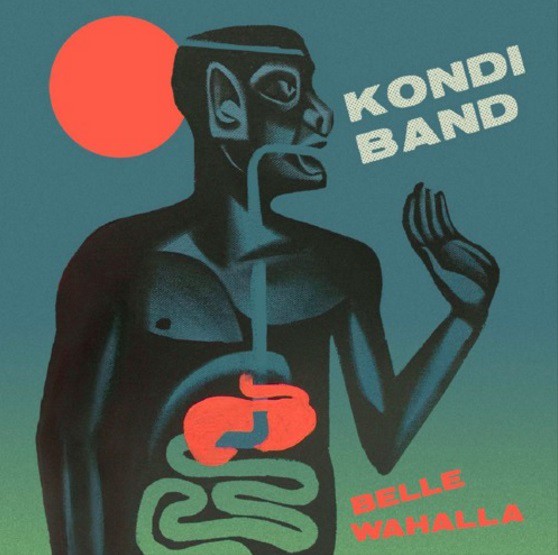

Kondi Band, "Yeanoh (Powe'hande Binga'dbe)" (Cervo Edit)

Who would you row through shit for?

If you are someone who wakes up each morning and scans the news to see what has happened in the world since the last time you looked you are aware that there is nothing nice about it anymore. The simple act of opening your inbox is an experience akin to waiting for an injection: You know it’s going to sting, you’re just not sure how bad it will be. So let me tell you this: The best thing you will see this morning is a sentence like, “Lacking nipples, cockroaches cannot be milked in the county fair sense,” and even that leads to a less pleasant story than you would expect from such an admission.

The only other thing out there today that might not make you want to cry contains the line, “I will row through shit for you, America,” but sadly it is neither a metaphor nor an excerpt from Hillary Clinton’s acceptance speech.

It’s going to be that kind of day, clearly, and that is clearly the kind of day it’s going to be for a string of days that stretch endlessly out toward the horizon. This, though, is something that should bring you at least a tiny bit of enjoyment. I mean, I hope it does. At the very least no cockroaches were milked in the making of it. As far as I know.