Michael Mayer & Agoria, "Blackbird Has Spoken"

Guess what’s just around the corner.

You know what? It’s four weeks to Labor Day. Whatever you had planned for this summer, you’d better do it soon, because before you know it the world around you is going to look like the cover of the last Apartments record. Are you really going to make your move in the next four weeks? Or maybe you have already given up on summer and are starting to convince yourself that autumn is when you’ll really make something happen? Sure you will! You just keep telling yourself that. What would you have to get up for each morning otherwise? In the meantime, here’s some music. Enjoy. And don’t be too hard on yourself. It was never going to happen anyway.

New York City, August 4, 2016

★★★★★ The clouds were fat and bright. The walk from the late and express-routed 1 train back up to the office was a little sweaty in the open expanses around 14th Street. A thick gray cloud moved overhead toward midday, but it proved to be of no significance. Little air currents moved among the people on the sidewalks, and a pleasant warmth soaked in during the moments when the air stilled. Smells were discrete and legible: pad Thai, and there was the cart right across the street. Two men sat on Siamese pipes flanking a clothing store entrance. Once again the light fled the streets by rush hour, but a secondhand glow came down from above. A stack of bright pink strokes, slightly downward-arching, marked the sunset, then gradually faded to dull purple, from top to bottom.

Best New Band Names, Ranked

SEO would be a good name for a band.

Just like web-based businesses that grab your eye with cleverly misspelled monikers (Flickr, Srsly, Pixlr, Timr), bands from Joe Jonas’ high-profile DNCE and the Weeknd to up-and-coming acts like Canadian electronic duo DVBBS, Mexican rapper MLKMN, Florida’s lo-fi XXYYXX, Canadian garage pop band JPNSGRLS and Norwegian producer CLMD get attention by forcing you to figure out what their all-cap handles (always with the all-cap) mean.

— Billboard: “What’s in a (Band) Name? These Days, Not Many Vowels: Here’s Why,” by Gil Kaufman

23. NDRS

22. CLRFRMS

21. KCKSKCKS

20. PSWRD1234!

19. RTRNJD

18. LSKLSFJL (N.B.: not to be confused with the Portland ME band LSKLSFJK)

17. PRTLNDM (N.B.: not to be confused with the Portland ME band PRTLNDRGN)

16. NB (N.B.: not to be confused with the Portland ME band N.B.:)

15. WWWDTSXDTCM

14. MNSNSSN

13. ZTFCCLRSL

12. JKFJBKD (N.B.: the LSKLSFJL side project, not the LSKLSFJK tribute act JKFJKBD)

11. KDNHKJH

10. HPSTRHMSNDWCH (pronounced “bánh mì”)

9. DVFGBG

8. DVFGBG JR

7. 8 (pronounced “nine”)

6. PRMDD

5. HCKJK

4. TTFN

3. NCTNVLMVCDNMRJNCSTSLCHLCCCCCCNE

2. LH00Q

1. NXTTMWNTUSNGWTHME

Happy Carol Lim and Humberto Leon Day!

It’s the day the Olympics open, but not the first day of the Olympic Games.

Technically speaking, this past Wednesday was “Day -2” of the Olympics, and today, Friday, is “Day 0” (that’s a zero not an oh). The first two days just had a lot of soccer, and today has a bit of archery. Tonight there will be the big flag spectacle where people have the matching country tracksuits and then there will probably be a big dance thing with eight thousand performers in insane costumes. Michael Phelps will carry the American flag but probably his shirt will be on!

Today is also the one day every two years when an über-cool fashion retailer with outlets in New York and Los Angeles and Tokyo will get a lot of accidental e-traffic. Congrats to its founders, Carol Lim and Humberto Leon! If I were them I’d offer some sort of promotional sale thing where like if you were looking for the Olympics but you got them instead and were totally honest about it and entered the promo code OOPSLYMPICS at checkout you’d get forty percent off? Two-hundred-dollar slip dresses are IN this season! Also these cargo shorts for women are on sale. Will I buy them? Or do you think a cargo dress is more my thing?

Opening Ceremony Otis Twill Cargo Shorts – WOMEN – Opening Ceremony – OPENING CEREMONY

Who am I kidding, it’s Frank Ocean day, A.K.A. just another day that Frank Ocean may or may not release an album. We’re waitinggggggggg…

West 4th and West 11th Streets, Manhattan

The waitress pointed you out to me over my shoulder. There you were, loitering conspicuous on the corner, outside the very small French restaurant whose inside tables were all empty and whose outside tables were all full. The waitress explained you were here first and I nodded my acceptance of your rightful prior claim to a table.

It’s an awkward thing, to wait on the street, trying not to look wolfish at the plates of the smugly seated. The best thing is to turn your back on them, and stroll around a bit, just to keep the air of nonchalance moving, in much the same way of a dehumidifier. You, sandy-haired, nondescript of jeans and genes both, had posted yourself one side of a lamppost to do this, so I took the other, and we commenced pretending to ignore each other. There we were, like a bad rom-com, each of us waiting for our person. And then I envisioned an even worse rom-com scenario in which we announced to the waitress that we were each other’s party. When our real partners arrived, they’d start a new table of their own. What montages might follow! What airport denouements! What kisses in the pouring rain! This, after all, was the prime neighborhood of normative narrative romance — the chimeric Manhattan of female characters who work entry-level media jobs yet live in prime West Village real estate.

Above the very small French restaurant was the apartment where I’d lived, for free (“house-sat” as the savior friend so generously called it) for one weird sad sick lonely summer. The sad sick loneliness had achieved new depths and dimensions — less bell jar, more polyhedron of thickening plexiglass — each time I ventured from my borrowed apartment into my borrowed neighborhood to try and borrow a life, or some life. Instead, I’d encounter a film crew every time. Or if not a film crew, then tourists taking pictures of the house where Sarah Jessica Parker’s character lived. Or Sarah Jessica Parker herself, walking fast in heels and sunglasses, living doors away from her character’s house. Now, I just felt glad to be old, glad to be waiting for my friend, and glad your friend arrived first so I could watch.

“There you both are!” you burst out, and there was something compensatory about your greeting, as if you’d planned and rehearsed it and now it had come out weird and too loud. It was just one person you greeted, a woman, so I glanced at her belly and yes, she was. “Good to see YOU,” you boomed — and she winced ever so slightly as you mwahed her cheek — “and good to see YOU!” — and now you were crouching down before her belly and spreading your hands at it, blazing your goofy grin, as if ready for the baby to pop open a window through the woman’s stomach and flip you a peace sign, sunglasses on. Your pregnant friend laughed in a strained way, and in glancing around, embarrassed, to see who was witnessing this little spectacle, she caught my eye. I smiled one of those quick smiles that says, Oh I’m not really looking at you and in that slice of a second before she looked away I saw that she was not your wife or girlfriend; she communicated this, as if it were important that I know, important that she disavow you. You didn’t notice because now you were a party of three and your table was ready.

Jacques Greene, "You Can't Deny"

Now the bad thing is happening.

Well, the terrible thing we were all dreading has happened, and now there’s no escape. I know how you look to me to make it better, but I am sorry to say that this time I have little left in my big bag of optimism to offer as amelioration. Much like everything else in life you are just going to have to live through whatever you can’t ignore. Maybe some music will help? If you can get past the vocal here — and I understand that wailing Chipmunk is a bridge too far for some people — you’ve got a pretty enjoyable song. It’s not enough but in the face of such horror what would be? Enjoy. [Via]

New York City, August 3, 2016

★★★★★ The air conditioner could stay off after sunrise, and the windows could stay open. Looking west to the Park, along the shining leaves of the street trees, brought on sneezing. The sun flared off people’s shoulders. Clouds moved unhurriedly, in various pleasant white shapes. The light made its way to the building tops and it was suddenly apparent, bright as it was, that the days were dwindling. The person at the opposite desk felt it in the same moment. Where pedestrians had been a sharply-lit parade for weeks, they now moved indistinctly in deep shadows, though it was not even six. People were moving faster than they had been. From Broadway, the light was off to the west, or away up ahead, receding. Between 29th and 30th, beside a plywood construction wall, there was a brief hot microclimate. The folding chairs in Greeley Square were full of people, as were the seats in the seating zone beyond, behind metal barriers in the roadway. Times Square was still sticky through sheer human effort. One of the desnudas had eschewed the usual flag decorations and had painted her nude body in a yellow Pikachu theme. A man had his wallet out and was talking to a CD hustler. Now and then in a crosswalk some late beam of sun stretching across the island touched a passing face. A carriage horse trotted by, heading home for the night. Past Columbus Circle the streets were calm again and entering twilight. Up in the apartment, though, the door opened into one last burst of light, making it seem as if a lamp had been left on by accident.

Can War Photography Be Beautiful?

David Shields’s book on the moral complications of aesthetic enjoyment

Imagine you’re reading the front page of the New York Times (in paper) some May morning in 2008. A story, below the fold, about a new world record in swimming catches your eye — or, rather, the accompanying photograph does. A swimmer’s head, shoulders, and arms are shown in profile, crashing through blue pool water. You trace the contours of his musculature and his swim cap; you note the perfect timing of the moment, the frozen white froth of splash around him. A band of yellow pool floats frames the bottom of the image; a line of red floats stretches behind his midsection; two blue lines recede further back. The swimmer almost seems to be emblazoned on a flag, amid these horizontal stripes of color. The photo is quite beautiful.

Flipping the page over, you see another photograph. A man with an olive complexion lies dead on a broad pile of rubble. There is deep red blood on his mouth and wrist, and a bright yellow blanket partially draped over one leg. Cradling him is another man, shirtless, his face buried in the dead man’s chest. At mid-ground, two green-fatigued soldiers observe the scene. The four main figures form a pyramidal shape, which is bisected by a long felled rod, bringing a nice symmetry to the image. The blood, and the blanket, and the deep blue of the mourner’s jeans pop off the page, and set these front-most figures apart from the bland grays and browns of the background. This photo is also quite beautiful.

A photograph always has dual citizenship: as a piece of documentation of the physical world, on the one hand, and as a visual object with aesthetic traits on the other. Even the most functional photo — a mug shot, say — can be appreciated for its framing, its colors, the look in the eye of the person it captures. Likewise, even the most abstract pure-art photos are documentary, too — a piece of the real world is reflected in them, post-production modification notwithstanding. Viewing a photo, then, is always both an informational experience, and one with the potential for pleasure.

Finding aesthetic enjoyment in the wet body of Michael Phelps on the front page of the Times in May 2008 poses little in the way of moral quandaries. It’s when the subject matter is something horrific, something tragic, something with actual human cost — a Georgian man killed by a Russian airstrike, being hopelessly gripped by his grieving relative — that finding beauty in an image, even taking pleasure in it, becomes troublesome.

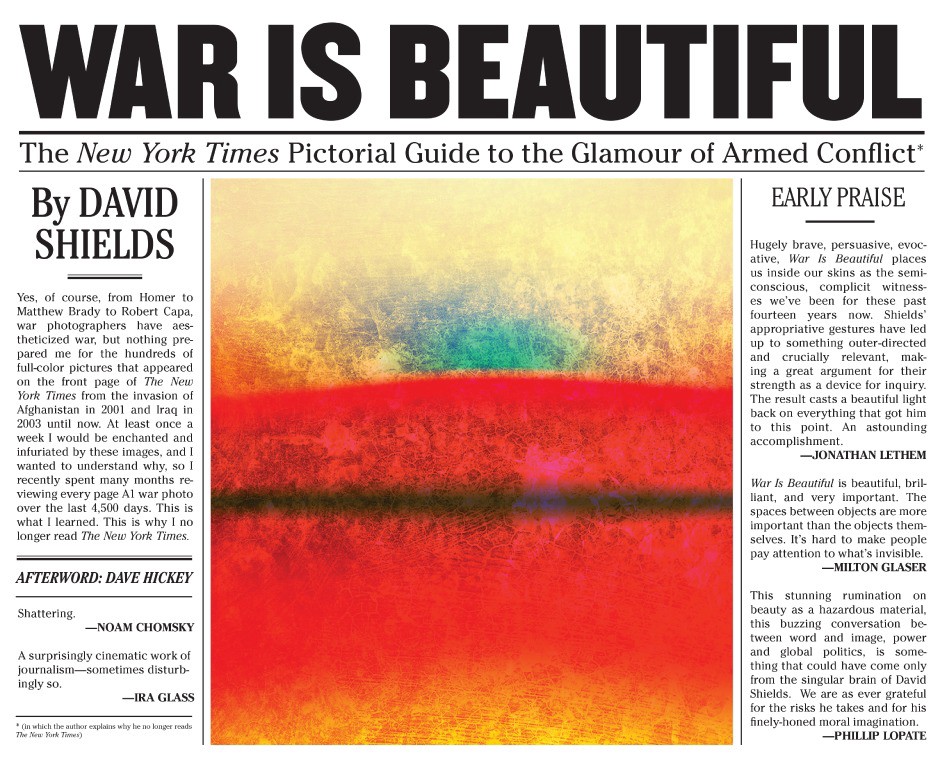

The latest book from bestselling author and ever-polarizing cultural agitator David Shields is called War Is Beautiful: The New York Times Pictorial Guide to the Glamour of Armed Conflict. It is an anti-Times polemic of very few words; the coffee-table critique consists largely of 53 arresting, full-color war photographs culled from the near-thousand that have been published on the front page of the paper from the period 2001 (the invasion of Afghanistan) to 2013. Shields — turning his sights to the journalistic establishment from his usual foe, the literary establishment — argues in a short introduction that, by publishing these photos, the Times has “glorified war through an unrelenting parade of beautiful images whose function is to sanctify the accompanying descriptions of battle, death, destruction, and displacement.” He divided the photos among ten chapters based around “certain visual tropes” that he found repeated as he browsed the archive: chapter titles include “Pieta,” “God,” and “Movie.” (Shields teaches creative writing at the University of Washington, my alma mater; I worked as his research assistant and have kept in touch with him.)

Shields put the book together after years of reading the paper of record every morning, going from being “entranced” by the frequently stunning war photography, to feeling “a mixture of rapture, bafflement, and repulsion.” “The Times’ photographic aesthetic,” as he terms it, is one of “epic grandeur,” reminiscent of the Iliad: heroic, sumptuous, and all in service of perpetuating a nationalistic “program.” “The Times uses its front-page war photographs to convey that a chaotic world is ultimately under control, encased within amber. In so doing, the paper of record promotes its institutional power as protector/curator of death-dealing democracy.”

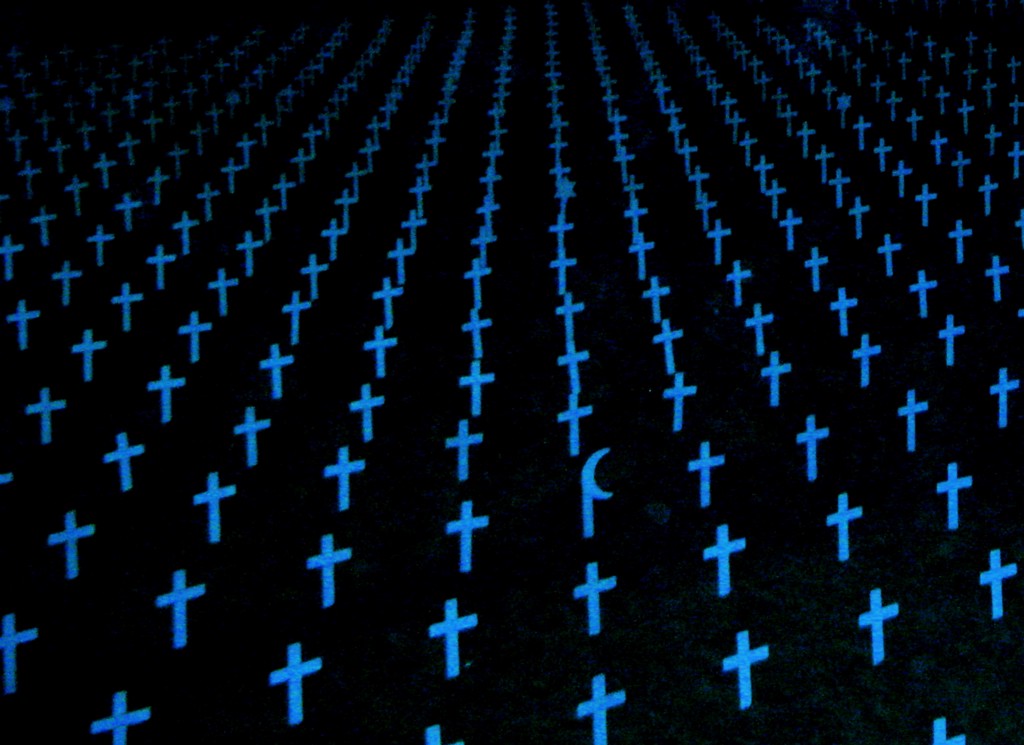

The photos in the book do seem to support Shields’s rather skeptical assessment of the Times. In the chapter titled “Nature,” one photo shows an American soldier meditatively pacing through a field of luminous pink poppies. Another soldier, in chapter “Father,” sits cross-legged and tenderly holds a small child wrapped in a tattered, bloodstained pink sweater. Even the corpses in the “Death” chapter seem at peace, dirt covering their skin in soft, glowing patinas of yellow.

Aside from the chapter headings and a few accompanying epigrams, there is no text on these pages. The gesture works because, stripped of the authoritative textual scaffolding of Page A1, we must look at the pictures for what they are, purely unto themselves: thoroughly aesthetic, painstakingly composed, and undeniably beautiful. But at the end of this silent, exquisite conflict-safari one arrives at a startling afterword by art critic Dave Hickey. Actually, Hickey says, the problem is not that the Times is beautifying war. The problem is that they’re trying to beautify war, and failing. Badly.

The central deception of the Times’ photographic aesthetic, writes Hickey, is that it is so heavily influenced by the visual conventions of the “Western pictorial tradition” that it is no longer representative of messy reality. “The photos in this book have grown old and familiar,” he writes. “They are no longer ‘lifelike,’ but rather ‘picture-like.’ The dense pictorial references preempt any hint of verisimilar-punch.” If the photos don’t shock us, it isn’t just because they’re beautiful; it’s because they look more like Baroque paintings than photographic exposures of an actually existing world full of actually existing war. While it was the seductive resplendence of the photos that bothered Shields, Hickey — like a good art critic — is too distracted by the overly obvious, derivative compositions to even be seduced.

For instance: One particularly “nicely balanced picture” — in which Uday Hussein’s smashed grand piano lies in rubble as two American soldiers climb an ornate spiral staircase in the background — is, says Hickey, “available in a hundred variations at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.” (Not by accident, this photo is found in the chapter titled “Painting.”) Elsewhere, you can find “a Rodin of two kneeling marines in a flat field.” Looking further, he says:

There is a field of flowers cropped to look like a neo “field painting.” There are three soldiers in silver light firing off shoulder-fired weapons — echoing Warhol’s Elvis paintings. There is a photograph taken in a fabric market with vertical panels of designed fabric — a flat, Robert Rauschenberg rip-off. There are two shell casings photographed from above that evoke Jasper Johns beer cans. There is a Dennis Hopper photograph of a beach, shot from the waterline with an empty chair and water bottle in the center and a line of palms and low buildings in the background. It could be Santa Monica, where I grew up.

Nowhere does Hickey call these photos “beautiful.” Rather, he refers to them as “Beaux Arts pantomimes”; “corporate folk art”; “Connecticut-living-room trash.”

The force of Shields’ decision to group the photos by “trope” is now felt in its full power: looking back through the book after reading Hickey’s essay, the tropes are all that’s left. If these were real people at some point, we can now see only generic characters; if these photos are movie stills, they’re all from bad movies. Even the image of the dead Georgian man is now suffused with a mass-manufactured sentimentality. The formal properties of the photograph — the angle, the framing, etc. — transform a tragedy into a cheesy Hollywood death scene. We wonder what the dead man’s poorly written last words were. We discover, finally, that it’s not that the Times has made war beautiful. It’s that it’s made it kitsch.

Shields’s inclusion of Hickey’s short, essential argument should have posed a major question for the book’s many critics, most of whom charged it with oversimplifying the project of war photography. Multiple reviewers have pointed out that war is not just violence, but is also filled with the kind of benign, dreamy moments chronicled in the book: soldiers playing baseball, or visiting Times Square, or getting a pat on the head from George W. Bush. “An accurate version of the totality of war has to show its many faces,” wrote Bryan Schatz in Mother Jones. “In truth, war may not be beautiful,” said Jordan G. Teicher in The New Republic, “but not every moment in a war zone is horrifying either.” True enough. Yet these critiques rest on the belief that Shields is simply calling for more horror — for war porn. They also understand the book to be addressing only the content of these photographs, and not their form. Both notions are wrong.

But then what is the book really saying? Is it that, as Shields suggests in his title and introduction, that the Times, as part of a tacit program of sanitizing state aggression abroad, is glamorizing war through its beautification? Or is it what Hickey writes — that the Times photos are actually aesthetic failures, morally dubious not because they beautify war but because they make it look so absurdly, surreally tacky?

The answer, of course, can only be some version of “both.” I was curious what Shields was going to say about all this at the book’s launch event in New York last November, particularly when an audience member inevitably asked the question no reviewer of the book has failed to ask: what should New York Times photographs look like, if not this? Despite being obvious, the question is crucial, particularly given the dense ambiguity the Shields-Hickey conundrum churns up. Shields responded by saying that providing this alternative was not the project of the book. However, he offered, “there is a much more hard-won aestheticism that the Times, in my view, could struggle with in a more muscular way.”

This desire for a “hard-won aestheticism,” whatever that might mean, seemed to me to be the hidden core of War Is Beautiful — the synthesis of Shield’s introduction, Hickey’s afterword, and the collection of photos itself. Seeking some clarification, I reached Shields via Skype to ask if he could explain what he meant by that phrase.

“I think the book happily embodies that contradiction,” Shields said. “On the one hand, I’m saying these pictures are too, too beautiful. On the other hand, I’m saying they’re not beautiful enough. But I think about the Picasso line: ‘the enemy of great art is good taste.’ That seems to me a terribly useful way of seeing it, in the sense that these pictures are really exquisitely, repellently tasteful.”

The idea of “taste” is actually much more germane here than “beauty”; commitment to “good taste,” meaning acceptable taste, is what directly produces the Connecticut living-room trash Hickey rails against. In fact, Shields said, “beauty” is precisely what these photos fail to capture. “I think people want to try and get me into a position of saying that somehow I’m against beauty,” he said. “It’s not as if I want to say that King Lear isn’t about violence and beautifully so, or Picasso’s Guernica isn’t about violence and beautifully so. I think people want to place me as a kind of Plato trying to banish the poets from the Republic — I don’t want any beauty, I don’t want any art. That’s not my position.” He continued:

It’s basically the Keats line: truth is beauty, beauty is truth, there’s nothing more to say. And to me, great art is incredibly beautiful, and the way it’s beautiful is it’s shot through with incredible truth-telling. This might be terribly old fashioned. But to me, the way the Times errs is that they have a really surface beauty, and it’s not truly beautiful because there’s no wrenching truth-telling beneath it. These might be very old fashioned, almost universalist terms, but that’s kind of the way that I see it. These pictures are falsely beautiful, like plastic flowers. They’d be more beautiful in the true sense of great art or great journalism, poetic journalism, if they aspired to tell more human truths.

“I think I’m making a relatively coherent case,” he concluded. “It’s, war is, quote, beautiful.”

Shields also finally answered the question of what war photography should look like. He named two photos he thinks achieved truth-telling beauty: the two most iconic images from the Vietnam War, by Nick Ut and Eddie Adams. “Those pictures are, to me, stunningly beautiful,” he said. “They accomplish journalistic art.” It’s not that they’re just more violent, or less carefully composed, than the photos in War Is Beautiful: it’s that they manage, according to Shields, to be more beautiful, despite — or, rather, because of — a deeper commitment to truth, in all its often-gory vividness. One can debate Shields’ assessments here. Hickey would probably make the point from the perspective of formal composition, of perspective and symmetry. But, looking at the Vietnam photos side-by-side with those in War Is Beautiful, one can’t help but be struck by a profound difference, one not merely reducible to different eras and different styles. It feels as though something is accessed in the Vietnam photos that just isn’t in the Times photos. It feels like the difference between good and bad art.

Beauty — or, at least, “beauty” — can sanitize and sanctify. But in its most rigorous, piercing, brutally head-on form, it can also force us to see. The false beauty of the Times photos attracts our gaze, seduces our sensibilities, even gives us a tingle of transient pleasure. But it does not do what truly beautiful war photography does: puncture us pitilessly with the immediacy of the real. Shields’ title is, finally, not ironic. War is, or can be, beautiful. And it is to be relentlessly looked at until it’s over.

Joseph Henry Staten lives in New York via Seattle. He’s written for Noisey, the Stranger, and elsewhere. He’s on Twitter.

How To Know If You're Ready To Do A Tweetstorm

Here’s what you need to think about before you grace the world with your wisdom.

Tweetstorms! They’re in the news, for some reason. It seems like everyone’s doing them! Maybe you want to be a part of this magic social media experience too! Sure, go ahead! But before you start a tweetstorm, ask yourself the following questions, which should help you focus on the task at hand and really determine whether you are ready to speak to the masses.

- Is what I have to say important?

2. Is it worth the time it will take for me to type it out?

3. Do its contents reflect an actual desire to impart knowledge on my part or is it just an obvious cry for attention?

4. Will what I share bring anything new to the conversation or am I just saying the same things everyone else has said before, but I am convinced they are more important because they are coming from me?

5. In a world which is already drowning in words that have no more meaning than a desire for acknowledgment on the part of the people who put them out there, will the torrent of verbiage I am about to inflict just add to the toxic landfill of the Internet?

6. Am I sure my opinion is so worthwhile that other people want to sit through a continuous short-burst monologue of it?

7. Twenty minutes after I post it and the likes and replies start trailing off will I feel empty at first and then increasingly embarrassed by the sheer narcissism it took to offer up my vapid and poorly-processed attempts at instruction? Will my cheeks burn with shame?

8. Who do I think I am? Why do I feel so alone? Am I about to cry?

9. Wait, were those likes genuine? Can I believe the magic of their sighs? Does anyone really like me? Are they all laughing at me? Do they see right through me? Does everyone know I’m faking it?

10. WHY WHY WHY DID I TWEETSTORM? I’m such an idiot. Ugh, they were all right about me. WHY WAS I EVEN BORN?

And that’s it! Once you’ve run through these questions, you’re ready to tweetstorm, because clearly if you are even considering doing something so showy, shallow and stupid you are not going to let a little thing like self-doubt get in your way! You probably don’t even know what self-doubt is! Good luck! I’m sure they’ll be falling all over each other to Storify your life-changing insights! What? No, I’ve just got a cramp in my hand, I am totally not making the “jerking off” motion at you! Get out of here, your public is waiting! Just make sure you retweet yourself in a couple of hours for the West Coast.

The Library of Dreams

An ancient encyclopedia of the subconscious

In 1899, Sigmund Freud published The Interpretation of Dreams, in which he argued that dreams encoded our subconscious (and usually, sexual) desires. In the century-plus since then, Freud has largely been left behind by psychologists, but no consensus view has emerged in its place. We still don’t know what dreams mean, or why we have them. Some argue that dreams are a way for the brain to integrate new information or process emotions. Others, that they are an ancient defense mechanism, designed to simulate threatening events. Some even argue that they are completely random, just electrical discharge ping-ponging through the cortex, for no reason but to keep us asleep.

The ancients were similarly divided about the origin of dreams. In Homer’s Greece, it was believed that dreams were messages from the gods. Aristotle thought they were a product of digestion, arising from the circulation of heat through the body during sleep. The physician Galen often diagnosed illnesses in his dreams, in which he also found cures. Plutarch argued dreams came from the Moon, stirred up by three daemons before coming down to Earth to enter the minds of men. The theologian Gregory of Nyssa dismissed dreams as fantastic nonsense. Tertullian, another theologian, said that they were where most people got their knowledge of God.

Most agreed that dreams had special meanings. They communicated messages from the gods, and they held information about the dreamer’s future, as well as that of his intimates. But how could this knowledge be accessed? Enter Artemidorus of Daldis, the world’s first true dream researcher. He was a citizen of Ephesus during the second century A.D. For him, the interpretation of dreams was a form of divination, one of the few legitimate ones: “the truth is spoken by sacrificers and bird-diviners and astrologers and observers of wonders and dream diviners and liver-examiners alone,” he wrote. Their work was under constant threat from the “false diviners,” whose numbers included “dice diviners, cheese-diviners, sieve-diviners, and necromancers.”

Artemidorus wanted to place dream interpretation in a firm rational basis. First, he consulted the works of his predecessors, most of which he found full of “error, relying as they did on superstition and conjecture.” To correct this, he did what any good researcher would do: he went out into the field, and gathered dreams. In the introduction to his book, Artemidorus explains that he traveled across modern-day Greece, Asia (Anatolia) and Italy, consorting “with the much-maligned diviners of the marketplace” and “listening patiently” to people of all social classes and professions as they told him “old dreams and their outcomes.” His interlocutors included orators, rhetors, tax collectors, convicts, perfumers, ship captains, soldiers, Roman Knights, Greek matrons, the rich, the poor, the sick and slaves. He interviewed athletes who hoped their dreams would tell them how they would fare in competitions, a philosopher whose dream foretold battles with a Cynic, and a wealthy woman who imagined that she was riding an elephant. Artemidorius made himself into an empiricist of fantasy, and he compiled his findings in a book called the Oneirocritica, or the Interpretation of Dreams.

The Oneirocritica is vast, and weird. Much of it consists of a list of various images that occur in dreams, and what each of these images meant for the life of the dreamer. Artemidorus worked backwards from the events that unfolded in the lives of his interviewees to figure out what a given dream, be it of figs, squids or inter-species sex, meant as a prediction for the future. Prophecy, in his telling isn’t guesswork, but fact. This makes the often-convoluted reasoning behind his interpretations stand out all the more, as when he writes that, “to imagine having the ears of an ass is good for philosophers alone, because the ass does not shift his ears quickly.”

Having two noses signifies discord. To imagine that one has teeth made of wax brings about immediate death. A chest that is shaggy and thick with hair is good and profitable for men, but for women it prophesies widowhood. Shaggy and luxuriant eyebrows are good for everyone, and most of all for women. These are all general cases, but Artemidorus also cites specific dreams and their outcomes, such as one by a certain man who imagined that he had bears’ paws for hands. Condemned to death, he fought wild beasts and, tied to a stake, was eaten by a bear.

Many of the dreams interpreted in the Oneirocritica seem fairly typical to a modern reader: dreams of flying, dreams about public nudity, about business transactions, children and fires (speaking before the Emperor, seeing hippogriffs or fighting in the arena, are more particular to his time). Sometimes, Artemidorus discusses situations that seem oddly specific, such as imagining dancing indoors alone while the rest of your family watches, juggling when you don’t know how (the former is good; the latter means you will benefit from trickeries and lies). At other times he says things that sound like blandly good advice, whether it be for the dream world or in waking life, as when he writes that “to be poor is beneficial to none, especially for orators and for all wordsmiths.”

Food appears frequently, as do animals. Artemidorus writes that to eat onions and garlic is harmful, but to possess them is good. Pumpkins signify “vain hopes.” Vegetables that emit an odor after being eaten, like radishes, “expose secrets and foster hatred towards one’s companions.” Flat cakes served plain are good, but served with cheese they signify “trickery and ambushes.” Soft fish are beneficial, but only to villainous men. Cats signify adulterers. Quail, for those who do not breed them, signify “unpleasant messages from across the sea.” Hemp is grievous for those who are afraid.

The dream world discovered by Artemidorus is a truly topsy-turvy domain, in which the most bizarre transgressions begin to seem normal. Cannibalism, coprophagy, and autophagy, all get their due — cannibalism is generally good, so long as it isn’t of one’s family; eating oneself is also good, but only for poor men. When it comes to dreams about sex, Artemidorus’s dreamers engage in what seems like every conceivable act of sexual congress. They have sex with gods, goddesses, heroes, emperors, animals, corpses, inanimate objects, celestial bodies and even vegetation sprouting from their own torsos (having sex with the Moon is good for sailors and others involved in nautical trades; for everyone else it indicates the onset of edema). Incest abounds. Dreams of sex with one’s mother are so common according to Artemidorus that “the sex itself is not enough to reveal what the dream signifies” and only the “combinations and positions of the bodies” can be relied on as an accurate key to their meaning.

In interviewing his subjects, Artemidorus tapped into a subterranean river of fantasy which he refused to censor. Thanks to that, his Oneirocritica is an encyclopedia of the subconscious of a bygone age. It is perhaps most precious in those moments when he intercedes the least, and presents whole dreams without commentary. Some are succinct tales of tragedy that recall the three-line novels of Félix Fénéon:

A certain man imagined that he skinned his own child and made a leather bottle out of him. On the following day, his child, falling into a river, drowned.

Others have all the grotesquerie and body-horror of a story by William Burroughs:

A certain man imagined that he had a mouth and teeth that were big and beautiful in his anus and that he spoke through it and ate through it and, whatever else one does with one’s mouth, it did all these things as well. Due to an indiscreet remark, being driven out he fled from his fatherland. I skip over stating the reasons, for the outcomes were fitting and rational.

Others still have a nightmare logic all their own. When coupled with their outcomes, they become like something out of Kafka, miniature parable of inexorable fate:

A certain person imagined that he lost his nose. And he happened to be a perfumer. He lost his store and ceased selling perfume due to his not having a nose. The same man, when he was no longer selling perfume, imagined that he did not have a nose. He was caught forging signatures and fled his own country. For anything that is absent from the face makes it dishonorable. The same man, while sick, imagined that he did not have a nose and, after a short while, he died. For the skulls of the dead have no nose.

In the Talmud, it is written that a dream which is not interpreted is like a letter which is not read. Artemidorus believed this wholeheartedly. Dreams were only the raw materials of his craft. For him, the true art lay in the finding their meaning. He was always at pains to emphasize that this was a very difficult task, and approached it less like a diviner and more like a detective. The dream interpreter had to learn everything he could about his subject — their social status, daily habits, business dealings, personal relationships, sex life, as well as details of local customs and cults that might figure into the dream. He had to observe the orientation of rooms and precise arrangement of objects and clothes. The cavalryman who dreamt that a maiden brought a wreath to his house — did he climb stairs to receive her or descend them? Even so, there was no guarantee of success. Dreams are elusive. For Artemidorus, meaning depends as much on the dreamer as the dream. The same dream could occur to many people, and never mean the same thing twice. Artemidorus gives an example of this from his travels, which he includes as a warning to his son about the difficulty of their profession.

Seven pregnant women dreamt seven dreams. In each dream the woman gave birth to a snake. In real life, each woman gave birth to a son. One became an excellent orator. Another, a thief. Another, a slave. Another, a prophet. For, Artemidorus explains, the serpent has a forked tongue just like an orator. And the serpent is sacred to the god, like a priest. And the “serpent does not move in straight lines.” Like meaning, it “slips through the tightest holes, always attempting to escape those who are looking to seize hold of it.”

Few people now believe that dreams can directly foretell the future. A century of modern dream research has seen the construction of databases of tens of thousands of dreams. To these, researchers have applied sophisticated statistical tools and coding schemes. The results get published in journals with titles like Dreaming and Consciousness and Cognition. We now know that most dreams are mundane, and reflect the dreamer’s daily life. Dreams of trauma are very vivid at first, and then gradually get less specific. The more you care or worry about something, the more likely you are to dream about it. These results seem fairly meager — little more than common sense. There may be something to the prophetic approach to dreams yet. If Artemidorus teaches us anything, it’s to listen closely, and read dreams as carefully as we would a poem,paying as much attention to the speaker as to the words, and be willing to find logic where there seems to be none.

Jacob Mikanowski sleeps to dream.