Sofie Winterson, "For as Long" (Bear Damen Rework)

We know, it’s hot.

It’s too hot to complain about the heat, so let’s just get to the music. Sofie Winterson’s “I Only Wanted You” was one of the best tracks of 2015, and her Kids EP was a ray of sunshine at the beginning of the year, so I’m very happy that a collection of Kids remixes is coming out September 2nd through Magnetron Music, containing versions from Fatima Yamaha and Waterlelyck and this Bear Damen rework of “For as Long.” Enjoy!

New York City, August 11, 2016

[No stars] There was blue in the sky but the humidity had not receded. The heat was prickly on the skin; the air resisted being inhaled. Something olive-colored was thriving in a sunny gutter puddle. The plastic lid on the iced coffee fogged up as soon as it was put in place, even in the air conditioning. A seemingly indifferent back-and-forth between clouds and sun abruptly included a flash of lightning and a crack of thunder. What came next was no less indeterminate, just more dramatically so: The sun and rain both intensified, till for a while showers were falling in yellow light. By dinnertime there was just the original stickiness, but afterward more lightning was flashing in the distance, where 72nd Street pointed off toward New Jersey. Later still, another hard rain came on. Somewhere up behind it, unseeable, there was supposed to be a meteor shower.

The Olympics of National Mottoes

Because every nation had to pick some words, and some are better than others

Best adaptation of the French revolution’s “three virtues” formula

“Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité” is the gold standard of national mottoes

Bronze: Madagascar, “Fitiavana, Tanindrazana, Fandrosoana (Love, Ancestral-land, progress)”

Silver: Gambia, “Progress, Peace, Prosperity”

Gold: 🏆Djibouti, “Unité, Égalité, Paix (Unity, Equality, Peace)”

Most egregious appropriation the French “three virtues” formula

Because imitation is the sincerest form of propaganda

Bronze: Kosovo, “Nderi, Detyra, Atdheu (Honour, Duty, Homeland)”

Silver: Côte d’Ivoire, “Union, Discipline, Travail (Unity, Discipline, Labor)”

Gold: 🏆United Arab Emirates, “Allah, al-Waṭan, al-Ra’īs (God, Nation, President)”

Most seemingly benign invocation of the Almighty

For the least-pushy appeals to the opiate of the masses

Bronze: Monaco, “Deo juvante (With God’s help)”

Silver: Samoa, “Fa’avae i le Atua Samoa (God be the Foundation of Samoa)”

Gold: 🏆Tonga, “Ko e ʻOtua mo Tonga ko hoku tofiʻa (God and Tonga are my Inheritance)

Most unabashedly non-sequitur

“Wait, huh?”

Bronze: Turks and Caicos Islands, “Beautiful By Nature, Clean By Choice”

Silver: Isle of Man, “Quocunque Ieceris Stabit (Whithersoever you throw it, it will stand)”

Gold: 🏆Canary Islands, “Oceano (Ocean)”

Most palatable call for national loyalty

When constantly asserting national obedience, do so eloquently

Bronze: Seychelles, “Finis coronat opus (The end crowns the work)”

Silver: Netherlands, “Je maintiendrai; Ik zal handhaven (I will maintain)”

Gold: 🏆Kenya, “Harambee (All pull together)”

Realest reality check on first-world privilege

A reminder that in parts of the world, liberty and equality are nice to haves

Bronze: Guinea-Bissau, “Unidade, Luta, Progresso (Unity, Struggle, Progress)”

Silver: Lesotho, “Khotso, Pula, Nala (Peace, rain, prosperity)”

Gold: 🏆Botswana, “Pula (Rain)”

Most badass motto from a not-complete-dick of a country

Because bark is cute when you have literally zero bite

Bronze: Scotland (unofficial), “Nemo Me Impune Lacessit (No-one Provokes Me with Impunity)”

Silver: Gibraltar, “Nulli Expugnabilis Hosti (Conquered by No Enemy)”

Gold: 🏆Swaziland, “Siyinqaba (We are the fortress)”

Most whimsically DGAF

Amid a swarm of assertion, pride and galvanization, these nations’ mottoes are pretty much just like ¯_(ツ)_/¯

Bronze: Peru, “Firme y feliz por la unión (Steady and happy for the union)”

Silver: Belize, “Sub umbra floreo (Under the shade I flourish)”

Gold: 🏆Bermuda, “Quo fata ferunt (Whither the fates take us)”

Best appeal to reason over God, country and other bullshit

Because “I’m rubber and you’re glue” is the ultimate comeback

Bronze: The Czech Republic, “Pravda vítězí (Truth prevails)”

Silver: India, “Satyameva Jayate (Reason alone triumphs)”

Gold: 🏆Chile, “Por la razón o la fuerza (Through reason or by force)”

Most ironic historical motto in hindsight

How did that work out for you guys?

Bronze: Republic of Florence, “Regna cadunt luxu surgunt virtutibus urbes! (Fall, you kingdoms of luxury, for the cities of virtue shall thrive!)”

Silver: Austria-Hungary, “Indivisibiliter ac Inseparabiliter (Indivisibly and Inseparably)”

Gold: 🏆Confederate States of America, “Deo Vindice (Under God, Our Vindicator)”

Most life-affirming motto by a country insignificant enough to afford to basically just say “fuck it”

A few we can actually all get behind

Bronze: Guatemala, “Libre Crezca Fecundo (Grow Free and Fertile)”

Silver: Vietnam, “Ðộc lập, Tự do, Hạnh phúc (Independence, Freedom and Happiness)”

Gold: 🏆Kiribati, “Te mauri, te raoi ao te tabomoa (Health, Peace and Prosperity)”

These are our champions for 2016. What other categories do you propose?

Gawker Media Blogs, Ranked

A listicle without commentary

19. Blood Copy

18. Gawker

17. Oddjack

16. Gridskipper

15. Jalopnik

14. Fleshbot

13. Kotaku

12. Valleywag

11. Idolator

10. Deadspin

9. Jezebel

8. Lifehacker

7. Gizmodo

6. Consumerist

5. Wonkette

4. Sploid

3. Defamer

2. io9

1. Screenhead

What Should The Olympics Sound Like?

A brief history of the Olympic song

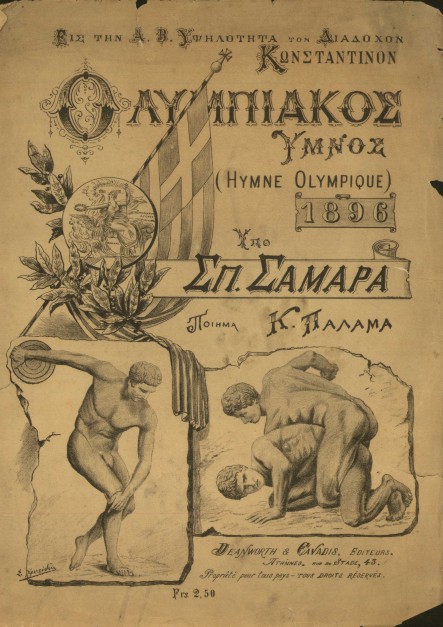

For well over a century, Olympic songs have been less the progeny of lyricists than of a handful of staple concepts. In 1896, the Greek poet Kostis Palamas inked into history a series of keywords that no Olympic songwriter since has been able to shake. His lyrics to composer Spyridon Samaras’s “Olympic Hymn,” which debuted at the opening ceremony to the first modern Olympiad in Athens, read like an itemized list of epic ideas: perseverance, strength, victory, beauty, and — not unrelatedly — a large body of water. “Ancient immortal Spirit” (Αρχαίο Πνεύμα αθάνατο) is the opening line of Palamas’s hymn. Twelve decades later, Katy Perry summoned that same image. “When you think the final nail is in; think again / Don’t be surprised, I will rise,” she sings in “Rise,” this year’s official Olympic song. The words picture her rising from the near-dead; the music video shows her parachute running, as if showcasing her skills at the NFL Scouting Combine.

In his latest prodigious book, The Games: A Global History of the Olympics, David Goldblatt marks 1984 as a turning point in Olympic music. Out with the Victorian loyalty to classical orchestral arrangements, in with marketable pop stars, preferably from the host country. “The combination of blockbuster movie and stadium mega-concert has often proved a bizarre medium through which to tell history,” he quips. “And that, for all the Olympian flummery, is what states and Olympic organizers have been paying up for.” Pop songs are indeed curious receptacles for history. But their shared compromised position is what connects Céline Dion to the fin-de-siècle Czech composer Josef Suk, pop stars to orchestral acts, a money-making juggernaut to a quaint quadrennial tradition. The pop songs have been surprisingly faithful to the motifs of the orchestral tradition. Just take the case of the composer Richard Strauss and Gloria Estefan.

In 1933, Strauss was approached by the Nazi regime to compose the song for the upcoming Games in Berlin in 1936. He walked a fine line between disinterested acquiescence and active ingratiation with the regime. As David Clay Large tells the story in his book Nazi Games: The Olympics of 1936, Strauss wrote to the Jewish writer Stefan Zweig, saying, “I’m killing time during the slack Advent season by composing an Olympic hymn for the proletarians.” Shortly thereafter, he seemed to have gotten over his contempt for his own project. Strauss asked for a private performance to preview the piece for Hitler. Echoing his Greek predecessors, he called his song “Olympische Hymne” and set the dramatic composition to the poet Robert Lubahn’s lyrics, which called for Kraft und Geist (“strength and spirit”) and athletic Herz (“heart”).

Sixty years later, Gloria Estefan put a jubilant spin on Strauss’s monumental tone at the 1996 Games in Atlanta with her song, “Reach.” Thematically, she hewed close to “Olympische Hymne,” ambitiously invoking the future (“I’m gonna be stronger”), the conditional (“I’d put my spirit to the test/ if I could reach”), and the purely hypothetical (“Those dreams you want with all of your heart”). If what made one of her best songs, “Rhythm Is Gonna Get You,” was its “tribal, on-the-loose and non-negotiably infectious” beat, as Wesley Morris put it, what unmakes one of her worst, “Reach,” are its chronologically challenged and corporately calculated lyrics. But who’s to say that Estefan’s song was more calculated than Strauss’s?

Most Olympic songs — even the early ones — have little to do with the Games, much to do with star power, and all to do with the disastrous attempt to calculate inspiration. Even Palamas and Samaras couldn’t escape the temptation to make tone-deaf demands to the athletes. “Give life and animation to these noble games!” exclaim a chorus of voices halfway through the “Olympic Hymn.” Olympic songs are not unlike the motivational posters you find in a Duty Free In-flight Shopping catalog — “Teamwork: Be strong enough to stand alone, be yourself enough to stand apart, but be wise enough to stand together when the time comes.” They want so desperately to telegraph motivation through song.

Whitney Houston is no exception. Taking the baton from her forerunners in her classic “One Moment in Time,” from the 1988 Games in Seoul, she pleads, “I want one moment in time / …when the answers are all up to me.” Reputable sources have put Houston’s at the summit of great Olympic songs. “‘One Moment in Time’ became the temporary new National Anthem,” Fuse gushed. For USA Today, it “perfectly encapsulates the spirit of the Games.” “It’s often replicated… but never duplicated” was how Bustle put it. Albert Hammond, Houston’s songwriter, didn’t mince words. “The best Olympic song for me — and not just because I wrote it — is ‘One Moment In Time,’” he told the British music magazine NME in the lead-up to the 2012 Games in London. “It’s an anthem. I can’t even remember the others.” But maybe Billboard unwittingly hit the nail on the head when they praised its “classic Olympic lyrics.” Strength, spirit, and heart, indeed:

I broke my heart

Fought every gain

To taste the sweet

I face the pain

I rise and fall

Yet through it all

This much remains

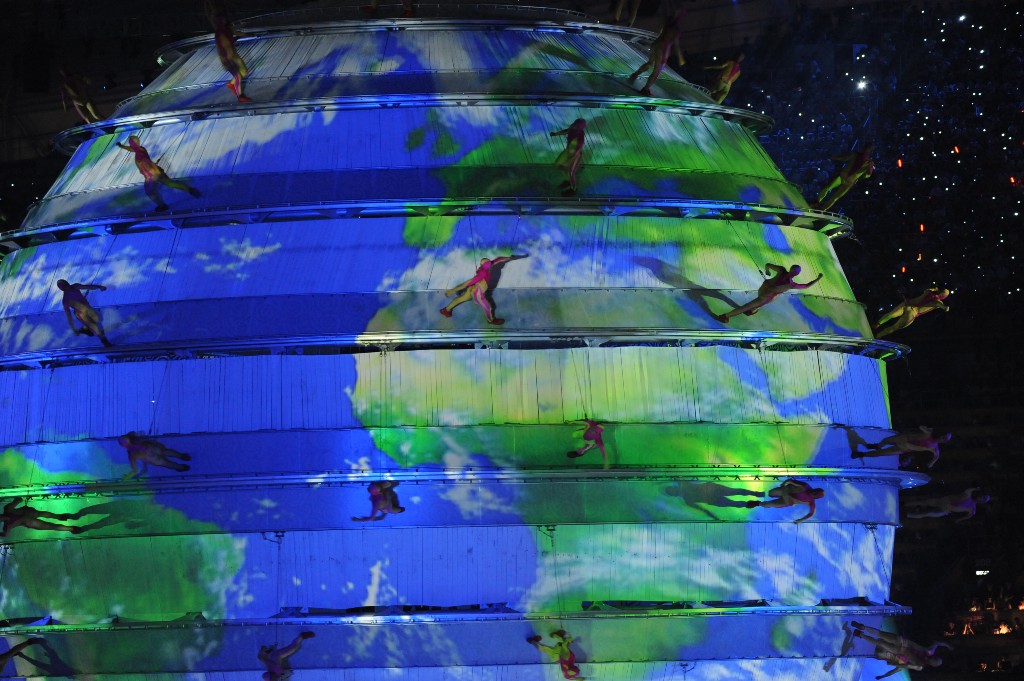

Large bodies of water appear in Olympic songs every once in a while. Montserrat Caballé and Freddie Mercury gave the Mediterranean a rhapsodic ode in “Barcelona,” the anthem for the ’92 Games: “Por ti seré gaviota de tu bella mar” (“For you, I’ll be the seagull to your beautiful sea”). Three Olympics later, Björk anthropomorphized the ocean in “Oceania,” the official song of the 2004 Games in Athens. “Oceania,” though, came four years too late — Athens isn’t near any ocean; it would have been a better fit for Sydney in 2000, when Björk’s ’90s luster hadn’t yet faded. In sum, it was a spectacular trainwreck.

“The song is all about how the ocean doesn’t see boundaries between countries and thinks everyone is the same,” Björk told the Independent. This wasn’t entirely evident halfway through the song during the opening ceremony. NBC’s Mary Carillo noticed during the broadcast that “Oceania” required color commentary and took it upon herself to provide it. She treated the performance as an Ikea chair to be assembled, guiding the audience through each step with the tone of an instruction manual. “The lyrics that Björk is singing are as if sung by the sea itself,” she said. “That’s why the sea image is on the big screen.” Carillo’s trademark deadpan didn’t do Björk any favors.

If Houston’s was, by consensus, the best, Mercury and Caballé’s “Barcelona” was the most memorable. “Barcelona” is to the ’92 Olympics what Randy Newman’s “I Love L.A.” is to Los Angeles sporting events, and it’s just as subject to revisionist history and appropriation. “Barcelona” wasn’t actually written for the Games; it was written as a one-off single. Mercury wanted to sing opera, Caballé, pop. But the song itself left too much on the cutting room floor, on both sides. Mercury’s voice couldn’t overcome the song’s tempered pace, yet that pace didn’t allow Caballé’s operatic vowels to fully bloom either. And, to make matters worse, their voices didn’t ever convincingly harmonize. “Barcelona” is a collage whose pattern is so obvious that it defeats the purpose, whose parts are so perfectly cut that they clash. As Time summarized it, “Where does this rank among Freddie Mercury songs? Going to go ahead and say in the lower 50%. Where does this rank among Olympic theme songs? Easily upper 10%.”

There’s one universal quality to Olympic songs: the lyrics are always laughably bad. The best that Muse could come up with, in their anthem to the 2012 Olympics in London, was five minutes of, “Race / It’s a race / But I’m gonna win / Yes, I’m gonna win.” Not exactly what one would expect from a band that claims George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four as a major inspiration. Where does this all leave us? Why are the lyrics to Olympic songs so terrible when the singers mostly aren’t? Does it all just boil down to the fact that none of them — or their lyricists — have ever competed athletically at a high level?

Maybe the better question is: What kind of songs should we have instead? Of all the major sporting events (whose corruption is on par with the IOC) the FIFA World Cup has the best formula. In recent tournaments, it’s relied on one famous mainstay, Shakira, and surrounded her with a rotating cast of characters, presumably representing local-ish color — K’Naan’s “Wavin’ Flag,” Coca-Cola’s official anthem for the 2010 World Cup in South Africa, is a good example. An added benefit of the World Cup’s handling of music is that, even if you happen to notice what the official songs are and you don’t like them, you’re not forced to listen to them often.

If the major problem with Olympic songs are their nauseating lyrics, then the Olympics should embrace genres of music that don’t care about them. Yes, exactly. I’m talking about worldbeat and new-age music. You know, “Adiemus,” the orchestral masterpiece put to fake Latin. Or Enigma’s “Return to Innocence,” whose chorus you think, instinctively, is Native American until you google it and realize that it’s sampled from a drinking song of Taiwanese aboriginal peoples. Someone might think that associating with new-age gibberish would be a non-starter for the International Olympic Committee. That someone would be wrong.

Worldbeat and new-age — I’m still not convinced there’s much of a difference — have the added benefit of making you feel like you’re at an ideal U.N. summit. (The often exotic or grandiose location of the Games helps.) A chorus of children booms West African-sounding lyrics in the background while vocalists in the foreground give Latin sounding syllables a pop inflection. It’s weirdly inspirational and uplifting, in that liberal guilt kind of way. Certainly it’s more inspirational than any of the Olympic songs that have graced the stage of an opening or closing ceremony in the last thirty years. Most importantly for the IOC, these songs will do a much better job than a famous pop star of inuring audiences to widespread corruption, the pillaging of the host city, and the inevitable steroid-plagued controversies. Go ahead. You try and get mad at the IOC while fifty children are singing, “A-na-ma-na coo-le ra-we / a-na-ma-na coo-le ra / a-na-ma-na coo-le ra-we a-ka-la.”

Bécquer Seguín teaches at Lawrence University. He writes regularly for The Nation and other magazines.

Tegan and Sara, "Hang on to the Night"

It’s a flying roach kind of weekend.

[Movie announcer voice] This weekend…. ROACHES. WILL. FLY.

Welcome to our third day of perpetual grossness, with no relief in sight. I suggest you huddle in front of the air conditioner until you need to go outside, and also that you not need to go outside. It’s just nast out there.

Hey, here’s a new video from Tegan and Sara. Enjoy! Good luck staying in this weekend.

New York City, August 10, 2016

★ The first daylight, long before the alarm went off, seemed to have come from a blue sky, but by proper waking time there were only clouds. A few advance raindrops were falling on a steady breeze. The air was thick, and it was even thicker down in the subway, and out on the streets by midday it was thicker still. The rain closed in, sending people into something between a hurry and a scurry. Then those showers went away, leaving a new reek of soggy things on the unthinned air. Sun kept going in and out, till it was impossible to keep track of how far along the afternoon had gone. The only constant was the air, heavy and disgusting long into the night. Well past midnight, it was impossible to go to sleep without having the air conditioner on.

The Detail From The Gawker Party That No One Is Talking About

The New York Times, W Magazine, and Politico all missed it.

Can the Academic Write? -- Part I

A conversation about style with David Wolf, commissioning editor at The Guardian Long Read.

Editors think that scholars are bad writers, and they say so often and rudely. Academics think that journalists are lazy thinkers, and they’re no more polite. Neither is right, I think, but the fields are so twain that nobody really bothers to think about the why or the how or the what next except super-intellectual magazines that nobody reads.

In the hope of addressing some of the issues that rub up at the academic/writerly tectonic ridge, I spoke with an old friend, David Wolf, my first-ever editor, who is now the commissioning editor of The Guardian’s Long Read section. Nobody’s ever pissed me off more on this topic, nor do I care so much about what anybody else has to say.

Part II is here.

What is academic writing?

JL: You’ve used the term “academic writing” with me before, as an insult. Where did you get this term, and what does it mean?

DW: Well, obviously the thought is not original to me! There’s a stereotype — which is wrong on many levels, and I’m not endorsing it — that journalists write good, plain, intelligible, clear sentences which everyone understands, whereas academics write torturous, confusing, hermetic, boring shit that no one would want to read unless they were also an academic. They don’t realize they’re doing this: they’re oblivious to the fact that they are writing in an academic way. This is the stereotype.

JL: This stereotype does match reality sometimes. Often an academic thinks they are clarifying when in fact they’re obfuscating, if the reader doesn’t share the same vocabulary of professional terms.

DW: Yeah, I think vocabulary is an important part of this — I would guess for many academics, their ideal readers will all have a similar intellectual framework, have read the same books, know the same lingo. But that isn’t going to be the case, of course, if you’re writing for a wider audience. Now, there are a lot of different ways — not just assuming readers will understand certain phrases and references — that academic writing can go wrong for a journalistic audience. Obviously there was that big argument about this in the nineties and early ’00s.

JL: What are you thinking of?

DW: When people talk about this subject, they always cite the Bad Writing Contest that Denis Dutton (who set up Arts and Letters Daily) started, and the year they gave it to Judith Butler. Butler was really angry, and she wrote this piece in the New York Times that spawned various responses to her response. There was a book partially edited by Jonathan Culler which collected responses to this debate that had been triggered by the “bad writing” thing. There was also a really good Lingua Franca piece investigating good and bad writing, which looked at it through an Adorno versus Orwell lens: Clarity is good! Clarity is bad! That kind of thing.

JL: I have always found the term bad “writing” very confusing, because I just don’t subscribe to it as a category. In the case of, say, someone writing about the Venerable Bede for Speculum, to a non-academic, that paper would be full of obfuscation and torturous terms and phrases and confusing things, but academic writing is for a specific, pre-existing community of scholars. You have to show that you understand everything that’s happened in the field, adding just a little bit of original modification to the discourse, otherwise there’s no reason that Speculum would publish you.

Non-academic readers encounter that prose and think that it is self-aggrandizing in its complexity, when it’s actually aiming for ultimate disambiguation of terms: “I’m not saying this, I’m saying that.” You have to deploy technical language to do that. Something else — something psychological — is going on when technical writing gets interpreted as torturous and annoying and undemocratic.

DW: I totally agree with you about the mushiness of this term. People talk about “good” and “bad” writing as if it’s obvious what they are. Like you said, in a journalistic context, extremely formal and exhaustive academic writing can come across as so pretentious and ridiculous when, in fact, there’s a lovely humbleness to it. The academic is saying, “Look! I’ve acknowledged all these people that have thought really hard about this” — they’re actually trying to give them their due, whilst differentiating their own view.

People talk about “good” and “bad” writing as if it’s obvious what they are.

But, I think, one way in which academics writing for journalistic audiences can go wrong is not appreciating that the world which you are writing for is completely different. If you’re an academic and you’re writing an academic paper published in an academic journal, the people who review you — it’s their job to review you. It’s not the job of the readers of The Guardian, say, to read you. They’re either going to read you because they’re interested, or they think it’s really important, or they’ll do it for pleasure or entertainment, but they’re not doing it out of any sense of duty.

I think this point about needing to get inside the mind of the reader applies to journalists as well, because often journalists are like, “Oh, my story about Chile is really, really important.” If you’re passionate enough to write a piece then you’re going to care deeply about the subject, but so much of good writing and editing is working out how to get readers who aren’t already interested to see how interesting the subject matter really is — whether it’s Chile or the Venerable Bede. In its worst form, this results in “dumbing down,” which academics rightly hate, but I certainly don’t think writing about a complex subject to a wider audience necessarily leads to dumbing down.

JL: Absolutely. In academic writing, basically all of a commercial editor’s job has already been done. Your audience is locked in; they already care. That’s interesting! Maybe editors like you feel insulted by the existence of academic writing because it makes you feel unimportant?

DW: I don’t think that’s true. But I would be interested to know what editors of academic journals think about this stuff. My impression is that the concern of those editors is the quality of the ideas and originality, rather than prose.

JL: Academic editors also must be rigorous about the positioning of those original ideas. An academic article absolutely must show where this bit of writing comes in the longer tradition of the field. In popular writing, not so much.

DW: I think good journalism, especially literary journalism, does do some positioning: just in a different way. There’s nothing more annoying to me as an editor than to get a piece or pitch that is written as if no one’s ever written about the topic before. It’s an encouraging sign in a pitch if the writer says, “The New Yorker did this piece, and Harper’s did this piece, but my piece takes a different angle.” If you just barrel in without showing any awareness of the other stuff that’s been written, then it’s probably not going to be good.

JL: But, crucially, that positioning doesn’t have to make it into the final copy of a commercial piece. The commercial writer doesn’t have to acknowledge ideas that are part of the culture. Ideas are not proprietary in the way that they are in scholarship.

DW: That’s true.

How do you edit an academic?

JL: I remember how ferocious you would get sometimes in your comments when you were editing my first few pieces. You would write things like, “Oh my god Jo, stop using this academic phrase.”

DW: I would only say, “Oh my god, stop saying this” to a friend! I wouldn’t do that to someone that I didn’t know. But it’s so much more fun editing people whom you can say that to.

JL: A classic one was “horizons,” in the sense of historical or conceptual horizons. I think it’s from Bakhtin? You would just write in track changes, “This means nothing.” I struggle a lot with having my citations edited out, so that my final copy cannot show that these are not just ideas that have sprung into my head from the ether.

DW: Well I do think that journalistic articles need to acknowledge where ideas have come from if they’re drawing upon specific thinkers. But obviously I can understand why an academic (or non-academic!) might feel uneasy simply saying “According to Bakhtin’s theory of x…,” when they are conscious of the fact that people have interpreted him in ten different ways and you can’t really be definitive. There is only so much hedging and qualifying you can do in an article for a non-specialist publication.

But it’s definitely true that good literary journalism has to import some of the caution of academia, in phrases like, “some scholars have suggested,” that kind of thing. You have to do it in a compressed form for the reasons we have already talked about. Readers aren’t automatically going to be interested, and they don’t want to go through every single interpretation of Bakhtin: thing number one, number two, number three, and so on. You have to do some more synthesizing, and corners are going to be cut. Of course, this can go too far. There is one journalistic extreme, which has none of the respect for academic caution, but that’s not the kind of thing I like!

JL: But this is especially applicable when people write about political topics like the history of, say, gender. Journalists’ extreme corner-cutting leads to corrosive discourse.

Journalists’ extreme corner-cutting leads to corrosive discourse.

DW: If I published a piece by you or anyone about a subject of interest to academics, and most of the academics who read it thought it was really bad, I would be very upset. I would feel like I hadn’t done my job properly, that the piece was a failure. To me, the idea of any good piece is that my mum (who is not an academic, doesn’t know anything about Derrida or Bakhtin or whatever) will enjoy it, some teenage kid wherever will enjoy it, and an academic who knew the subject would at worst think, “That was fine. It didn’t make me want to kill the author.” Hopefully, they will think, “That’s really interesting, I hadn’t thought about that.”

Your Tolkien piece, for example: I would hope that an academic could read it and, even if they’re not like, “Holy shit, I’ve never seen these ideas before,” they’re at least thinking, “Okay, that was a good piece.” It’s so, so, important to me that people who are experts in any of the subjects we are writing about in the Guardian Long Read should at least feel like we took their subject seriously and did justice to it.

JL: I think you are underestimating the vanity of academics and their rage when they see something in the public sphere that touches on their subject: their rage that they haven’t been explicitly cited, or that the writing is dumbing down the field. Academics often interpret popular journalism as a personal affront. They will not attribute the difference to the conventions of publication or the different style required. They will just think, “This is stupid.”

Academics often interpret popular journalism as a personal affront.

DW: Everyone’s like that, really. I know journalists who say, “Oh, that fucking guy has written about Russia. He doesn’t know shit about Russia. He doesn’t even speak Russian.” Journalists are just the same. There is a lot of bad writing in the public sphere about stuff that scholars know about. I think scholars have a right to be annoyed by that.

JL: But most academics do not know that writers don’t choose their own headline. Most people, including academics, will look at the headline and illustrations and pullquotes and be like: trash!

DW: That’s true. But there’s a reason why editors don’t let writers write their own headlines. They write the worst headlines in the world.

Josephine Livingstone is a writer and academic in New York.

Out Of Cite

Internet writers are standing on each others’ shoulders just so they can be first.

The fact of timely cultural criticism on the internet inspires a palpable anxiety amongst writers on concerns of originality and the desire to be first. The incredibly scant window of time to not only pitch but then produce a piece of writing on a given album drop or public feud or bigoted soundbite creates somewhat of a conflation between the two. Ricky Bobby and whatnot. The problem of the harried response piece and the pressures imposed upon writers is an adjacent issue, one captured succinctly in a tweet from author Roxane Gay in the wake of Lemonade. I’m more concerned with the consequence — when writers shy away from prior work as if acknowledging precedent sullies originality.

Writing an essay on lemonade and a lemonade syllabus. Want to take my time but goddamn. Mofos churning content out at a frightening pace.

— @rgay

I like to write about the internet, for the internet. The last thing I wrote about the internet was an idea I’d been toying with for almost a year, accumulating quite the messy collection of excerpts, tweet links, screenshots, and shitpics spread across multiple mediums and devices. Not everything made it, of course, but still the final product was the most densely citational essay I’d ever done, including academic work. During final edits of the thing — like, the final edit — I came across Amanda Hess’s great “Hands Off My Smiley Face” in the New York Times. As I read through the piece and its insights I felt gutted, as if a year of thinking, weeks of drafts, and 2000 words instantly became obsolete.

She’d gotten there first.

First is relative. Topically, almost nobody is first in anything, even the long-dead thinkers who get canonized as such. But originality is not anchored to topical firsts, but rather new ideas. When a new paper is published, it’s considered innovative not because the researchers were the first to work with the materials but because they do so differently, or better. Lauren Chief Elk-Young Bear writing on drone feminism is hardly the first to talk about either, but the proposition she comes to in consideration of what’s been done prior is all her own.

This is why writers have editors: to skirt around a splattered mess of emotional attachments and see what’s on the page for what it really is. To help a writer see that topic similarity is not akin to redundancy. That two people can observe the same trend differently, yet also inform each other. That’s how you have a conversation. What’s more important, to be mythically “first” or advance conversation about a subject matter in the richest way possible?

In the Chronicle of Higher Education, in an article titled, “Erasing the Pop-Culture Scholar, One Click at a Time,” professors Amanda Ann Klein (East Carolina University) and Kristen Warner (University of Alabama) take on the “pop-culture thinkpiece” and address the genre’s unwillingness to seek expertise when it comes to interpretation and cultural criticism(ish). What’s often assumed to be untrodden ground — consider the now passé, “why is nobody talking about X” style — is actually a phenomenon many somebody elses have been thinking about for quite awhile, which writers would see if they only bothered to look.

What’s more important, to be mythically “first” or advance conversation about a subject matter in the richest way possible?

Klein and Warner aren’t merciful in taking the “thinkpiece” to task, though for those who actually read the essay entire it’s clear their concern scales larger than the freelancer making a quick buck for an ode to Beyoncé’s hair (hii!). Klein and Warner point us to a general trend where the skills needed to understand the objects around us are increasingly devalued in an era when the humanities are dying and a decidedly inhumane gig / share economy thrives.

Erasing the Pop-Culture Scholar, One Click at a Time

As they also point out, perhaps overly briefly, there’s a reason academia has such a bad rep in terms engagement (lack thereof) with the general public. Not only are many peer-reviewed journals egregiously expensive, the language employed in this type of writing is intended for such niche audiences even discipline-adjacent scholars might have difficulty with their content.

Even as online media companies accrue a powerhouse of resources for their talent that could theoretically provide staff writers with subscriptions to Project Muse and EBSCO, the latter issue — audience and readability — remains. And while these gatekeeping strategies exist, blaming the writer who didn’t utilize the great wealth of research on the feminization of vocal fry for his 1200-word defense of Kim Kardashian feels misplaced. As UVA professor and Slate critic Jack Hamilton points out, pop culture scholarship would not exist without a rigorous tradition of non-academic writing such as music journalism and film criticism. Plenty scholars won’t think to survey even popular online publications before waxing academic on Beyoncé or Miley Cyrus behind a paywall.

Suffice it to say, I am completely uninterested in the aca versus non-aca portion of the conversation. As a graduate student whose bylines don’t even brush the upper echelon of the journalist canon, nor anything like an academic journal, I hardly have a tenable position on either side. As someone who writes for the internet in part to subsidize overpriced living on a undersized stipend in a field that may not even exist by the next time I emerge from the stacks, I am very much ambivalent about the fate of a scholarship that won’t give a fuck about what I have to say the second my proxy access expires.

Even taking the academy as nonexistent — which for all its accessibility, it might as well be — there’s something about a tendency for internet writers not to even cite their own peers that points to a more troubling problem in terms of the voices that get left out. We should talk about citation generally, as a community-building practice, as a discussion enriching practice, and as a practice that can undo or prevent the force of erasure in terms of marginalized voices. I want us to talk about citation as a loving practice.

When last week W ran a 16-part virtual roundtable on their cover girl, I wasn’t surprised at all to see Black folks asking why, out of 14 writers featured to dissect Rihanna’s public image, not one Black woman could be found to share her thoughts. I and others queried editor Erik Maza about the absence. Perhaps the addition could have prevented such disastrous language as “Post-Verbal Pop Star” or the bad on top of worst responses from resident non-Black, non-West Indian writers at Jezebel and Huffpost, to whom Jamaican ascribes all things Island patois. Perhaps. Naturally, this is all speculation because only one Black person and no Black women were asked to weigh-in for any of this writing, citationally or otherwise. My question was met with silence.

It’s a silence replicated not just by leaving out bodies, literally, but in obscuring a name. I feel comfortable in declaring Black femmes the best cultural critics the contemporary has to offer. Yet so rarely are Black femmes credited with expert contributions. I think of a certain essay on Lemonade, published a solid month post-release in one of those aforementioned upper echelon publications. Despite the writings and stylings of so many in the album’s wake, to read that essay one might think that, aside from the past’s intertexts, the only person available to comment on Beyoncé was a superstar academic and public intellectual.

Als on Beyoncé compared to say, Hannah Giorgis’s “Drake Belongs To Black Women” or Aria Dean’s “Rich Meme, Poor Meme,” it’s as if the latter two are living in a completely different internet. The age-old tradition of (Black) women citing (Black) women is alive and adaptive to digital spaces. We can certainly advance cultural thought by our damn selves, but fuck me before I take erasure of our thought lightly. And it’s hardly a coincidence Black women seem to talk about plagiarism more than anybody else. Trudy. Akilah Hughes. Jamie Nesbitt Golden. Angela aka The Kitchenista. Some of late, some for years, they and others have created the necessary discussions on and proposed strategies against the poaching that takes place carte blanche online and elsewhere.

(Alongside the conflation of original and first, there seems to be confusion over the relationship between citation and plagiarism. The plagiarism = theft language might hurt us here; many think “working off of” or “being inspired by” doesn’t require acknowledgement. That only a blatant act of Cmd C+V — à la Melania Trump — without attribution counts.)

It’s hardly a coincidence Black women seem to talk about plagiarism more than anybody else.

Citation masks a lack with presence, but also presence with a lack. At worst, the intellectual property of the internet’s most valuable players is mined without compensation or credit; at best, writers waste words reinventing the wheel and projecting an unfinishedness to questions others have already answered. Just like “intersectionality” should signal Kimberlé W. Crenshaw, “misogynoir” Moya Bailey and Trudy, anything akin to discussion on “it me” should conjure Safy-Hallan Farah and her work. “On fleek” deserves credit to Peaches Monroee, just as online appropriation should consider Doreen St. Félix. Any question about Black virality benefits from Niela Orr, Aisha Harris, Fidel Martinez. You can’t really cover Drake without Amani Bin Shikhan. We’re at the point where to write anything on digital culture requires a hefty collection of prior readings.

Black Teens Are Breaking The Internet And Seeing None Of The Profits

Nobody’s mad that you won’t cite Foucault on every gesture to social constructs or Althusser on ideology (in fact, please don’t). Thankfully there’s way cooler stuff out there, writers and thinkers and tweeters and artists sharing what they know and making revelations on platforms accessible to anybody with an internet connection. Read them and be smarter for it. Cite them so we all are.