Jonathan Mann, "The Ballad Of Steven Slater"

Prolific Youtubist Jonathan Mann has written and recorded a song celebrating everybody’s favorite new “bandit hero” style folk icon, Steven Slater. (A DJ on 101.9 played the song last night, followed by The Replacement’s “Waitress In the Sky,” which was a nice touch.) It’s not quite “four dead in Ohio!” but it seems like it could be having a similar effect on society. College English professor Lynne Rosenthal was thrown out of a Manhattan Starbucks yesterday after refusing to order a bagel and coffee in accordance with the coffee corporation’s famously frustrating menu-speak. “I just wanted a multigrain bagel,” Rosenthal told The New York Post. “I refused to say ‘without butter or cheese.’ When you go to Burger King, you don’t have to list the six things you don’t want. Linguistically, it’s stupid, and I’m a stickler for correct English.”

America's Adopted Koreans, Part 1: What's Your Name?

by Sarah Idzik

When I was in sixth grade, a girl I knew accosted me one day in the stairwell, staring up at something on my face. When I tried to sidestep, she followed. I asked what she was looking at.

“Don’t you know?” she said. I shook my head. “It’s your nose!”

I stared at her uncomprehendingly. “Your nose! It’s flat right here!” She rubbed her own nose bridge with her fingers. “See how mine has a bump? Yours doesn’t.”

I felt the same place on my own nose. She was right: Where she had a ridge, sprinkled with freckles, I had none. I never would have noticed the difference if she hadn’t pointed it out.

I was adopted from South Korea in 1986, when I was three months old. That year, 6,150 Korean children were adopted to the United States-59% of all children adopted in the U.S. that year. Americans had begun their love affair with Korean adoption in 1955, when an Oregon farmer named Harry Holt and his wife first adopted eight South Korean children orphaned by the Korean War. But an increasing number of South Korean infants born out of wedlock to working-class mothers, typically factory workers, and a decreasing number of domestic U.S. adoptions due to socioeconomic factors like the availability of birth control and legalized abortion contributed to an explosion in the numbers of Korean adoptions to the U.S., which hit their peak right around 1986.

The vast majority of the adoptive American parents were white.

This meant a lot of Asian babies growing up in white communities, with white families, friends, and classmates-essentially, a lot of Asian babies growing up culturally white. More than 100,000 South Koreans have been adopted to the U.S. since 1958, making us the largest group of transracial adoptees in this country. But little is commonly known about the unique adult (or nearly adult) Korean adoptee experience in the United States, in particular the effects of growing up in white communities on the identities of Korean adoptees.

Last year, the Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute published a study on identity and adoption, the most comprehensive of its kind to date. Of the 179 respondents surveyed who were born in South Korea and adopted by two white parents, 78% percent said that they considered themselves to be-or wanted to be-white as children.

This is why, as an eleven-year-old growing up in a smallish, very predominantly white Pittsburgh suburb, I couldn’t guess what it was my fellow classmate was staring at. As far as I was concerned, I looked just like the girl with the freckles. In the 80s, the prevailing approach to raising adopted Asian babies was, for the most part, to assimilate them. There is a wealth of good intentions at the heart of this approach, but also a very generous dose of idealism. I had a great upbringing and a wonderful family in which I never doubted my place, but no matter how determined we are as a society to insist that our nontraditional families are just the same as all other American families, this is only true up to a certain point. The dynamics and relationships in my family were no different from those of my white peers, but there was one key difference between us and them: my brother and I just did not look like our parents. And while that was an easy thing for family to overlook, it isn’t necessarily taken for granted by everyone else.

“The people that loved me, and my real friends, they didn’t see it,” Rachel, an old friend who was adopted at six months old and grew up in the same town, told me. “And while I knew I wasn’t white, when you’re in a protective bubble, you almost forget that as easy it is for loved ones to not see you, it’s just as easy for you to stick out to others… I know that I look different. But when I’m walking around or living life, I don’t even think that I stick out.”

Rachel said that she wanted to be white when she was younger, but now, “I want to be understood as a person… I want to be seen as an individual, and not with an entire ‘Asian’ group. I want to be just another person, just like everybody else.”

I felt the same way growing up. I wanted desperately to fit in, to be seen as just another kid and not as one out of the four Asians at school. Every moment of casual discrimination felt like a betrayal by the culture that I felt I belonged to, or that I longed to belong to. The encounter with the girl who pointed out my lack of a nose bridge wasn’t just confusing and disorienting; it was, in its own way, traumatizing. 80% of adopted Koreans in the Adoption Institute study responded that they had experienced racial discrimination from strangers. 75% said they’d experienced it with classmates, and 48% reported having negative race-related experiences with childhood friends.

The result is often a sense of identity in constant crisis. We are, in many ways, people in between cultures, sometimes fondly referred to as Twinkies: yellow on the outside, white on the inside. “My friends often tell me, ‘Caroline, you’re the whitest Asian we know,’” Caroline, a 24-year-old from Oklahoma who was adopted from Korea when she was three months old, told me. “It’s true and I’m okay with that.” That’s a sentiment I hear a lot too, about myself. But being in between cultures often results in feeling out of place in both. In high school, I made light of my being different by keeping up running jokes with my friends about being Asian, but when I got to college and saw that a large portion of my classmates were Asian, I knew that I couldn’t make the same jokes, because I had no real claim to that culture.

Rachel admits to feeling guilty when other Asians can tell her ethnicity, because she “can’t tell them what they are and I can’t tell them anything about being Korean.” She cops to awkwardness at the hair salon she goes to, where she can’t satisfactorily answer the questions of her Korean hairdresser about whether she likes kimchi or has been to the local Korean church. “Have you ever thought that having an American name hurt you?” she asked me. “White people say, ‘What’s your name?’And I say, ‘Rachel Kaylor.’ And they say, ‘That’s not Asian.’ And then Asian people may ask me and they wonder, ‘That’s not Asian. What was your Asian name and why didn’t you keep it?’”

There are signs of improvement, of course. As we all get older, we will likely become more and more comfortable with who we are, and with our unique place in American society. Most respondents in the Adoption Institute study said that they had developed some comfort with their race/ethnicity as adults.

But a not-insignificant 34% responded that they still remain uncomfortable or only somewhat comfortable with their race/ethnicity. There’s a long way to go yet before the Asian adoptee community in the U.S., still a fairly young, scattered, and in many ways, unknown group, is entirely comfortable in its own skin… flat nose bridge and all.

Sarah Idzik is a writer living in Chicago. She cannot point you to the nearest Korean grocery.

'Scott Pilgrim' Versus Itself

by Mike Barthel

I don’t want to be the guy arguing that a movie adaptation of a comic book doesn’t do justice to the original comic. I especially don’t want to be the one doing that about Scott Pilgrim Vs. The World, because there have already been dark accusations about it being too fanboyish, and I am most definitely a fanboy for Scott Pilgrim the comic book. But the little things that bug me about the movie all ultimately feed into one big complaint: the wonderful treatment of female characters in the comic book gets lost in the transition to the big screen. It’s what happens when you make a big action-filled summer film. But it’s not good that this requires the female characters and their particular relationships to be swept under the rug.

Let me back up, though, and explain why I love the comic so much, because I think you may be missing out on something pretty wonderful if you’re dismissing the movie as another twee Michael Cera vehicle. Scott Pilgrim the comic was written by a guy named Bryan Lee O’Malley and published in six manga-sized volumes between 2004 and 2010. Though taking a lot of structural cues from Japanese comics-see Dan Kois’ wonderful explanation here, which is absolutely vital and way more knowledgeable about Scott Pilgrim’s relationship to comics than I can be-it’s strikingly different from other indie/art comics, and even unlike the superhero comics that generally get made into big-screen adaptations (it’s comparable more to Archie, since none of the characters are super and they’re all stuck permanently in adolescence).

The main character, Scott Pilgrim, is a recent college graduate who lives in a one-bed apartment in Toronto with his gay roommate, plays bass in a band called Sex Bob-omb, and falls in love with a cute American girl named Ramona Flowers who dyes her hair and is awesome.

The story isn’t about super powers or life-or-death situations or the fate of the world. It’s about love, and being young, and it won an award for being the best humor comic of 2010, because it is hilarious. The people it’s about aren’t particularly exceptional, and the things they go through-hooking up, trying to find jobs, dealing with their past-aren’t either. It’s just that the reality in their universe makes their normal actions metaphorically resonant in wonderful and complex ways.

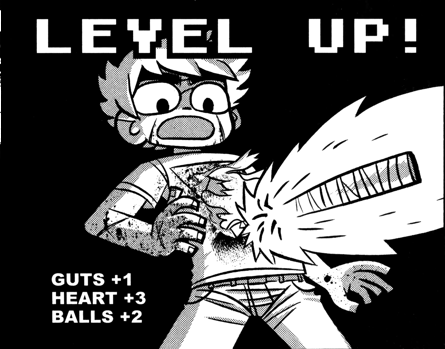

The central conceit of Scott Pilgrim is this: what if the imaginary realities of the pop culture a generation grew up with were reflected in physical reality? So, for instance, the generation that grew up with manga and video games resolved its emotional disputes through kung-fu fights, and when someone was defeated they turned into a handful of coins? What if your emotional maturation were reflected in visible improvements in your personal stats (“Heart +1,” etc.) and being a vegan gave you super powers? What if music was so powerful and so important that really good bands could cause explosions with the force of their rocking?

And, most importantly, what if this was all absolutely normal-so normal that when someone turns into coins or plucks a sword out of their chests or trashes a concert hall with their performance, everyone was kind of bored and disappointed and wandered off to get pizza?

Games are an essentially new art form that only that particular generation-O’Malley’s generation-have grown up knowing. So if movies or TV changed the way earlier generations experienced the world, so must video games have changed how this generation experiences the world.

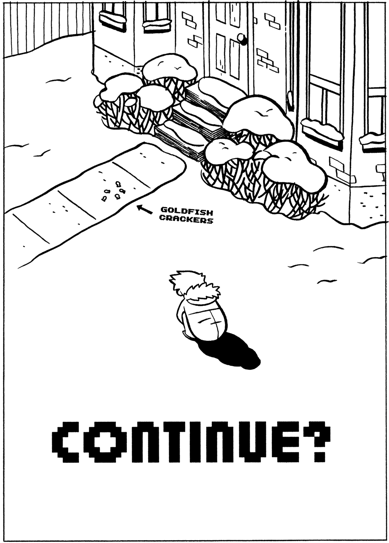

The physical presence of game mechanics in the midst of one dude’s post-college emotional malaise makes sense because it’s an accurate externalization of his thought process. There are no thought balloons in Scott Pilgrim-either someone speaks, or we get a picture of their thoughts. Thoughts never come in words, only in pictures, and that, to me, seems like a good way of representing how confused predults haphazardly try and gain control of their lives.

What makes Scott Pilgrim not just a good comic but a great piece of art (seriously!) is that it doesn’t just find a series of fun stories to tell within this reality, but tells one story (its six books constitute the entirety of the series, and tell one continuous narrative) that explores the consequences of this outlook for the people afflicted by it-their ability to connect with each other, and to accept the non-metaphorical parts of reality that can’t be resolved through boss fights.

While in the first book the series looks to be about a straightforward progression of fights for Ramona’s love, Ramona is not only given agency (!!!) but emotional issues of her own to deal with, and by the fourth volume, the series characters have all began to sunk into a collective malaise that will feel very, very familiar to anyone who lived through a shiftless mid-twenties. The final volume unexpectedly climaxes with a fight not between Scott and one of Ramona’s evil exes, but between Scott and himself-and he only wins by losing, allowing the romantic self-image of himself as a hero to coexist with the reality that we’re never always victims or victors; we’re victimizers, too.

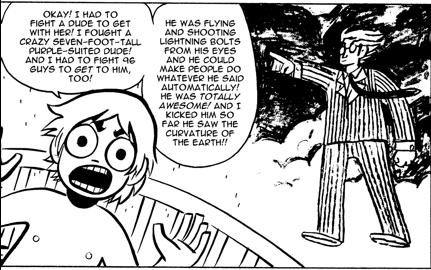

This progression spans the length of the series. In the third book, Ramona finds out that Scott and the band’s drummer, Kim, dated in high school. When she asks Scott for the details, Scott demurs, but when Ramona insists, he bursts out with a story about having to fight a “crazy seven-foot-tall purple-suited dude” (see above). Ramona takes this as sarcasm, but we know from the opening of the second book that he does, in fact, have a memory of fighting said dude (in an homage to the classic NES game River City Ransom) for Kim.

In the final volume, though, an epicly moping Scott goes to visit Kim in the country, where she breaks him out of his funk by reminding him that he didn’t fight a giant dude-he just punched a defenseless kid named Simon Lee who had only held hands with the object of his affection.

Scott’s coming to terms with this-with the fact that he had built up prime examples of his own dickishness into self-defining stories of heroism-provides one emotional climax. But the other comes when Ramona has a similar revelation in the midst of the final boss fight against her seventh evil ex, Gideon.

Though it’s easy to think of Ramona as a classic manic pixie dream girl (the NYT review even compares her character, cringingly, to ur-MPDG Kate Winslet in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind), she’s just as problematic a character as Scott. It’s no accident, after all, that all of her exes were willing to band together into a league dedicated to wrecking her future relationships. She burned them all pretty bad.

In the end, it turns out Ramona’s just been on her own epic mope alone in the country. She hasn’t been running from man to man, she been dealing with her own shit, because healthy relationships aren’t about one person saving the other or making them better-they’re about two people filling in the gaps where their partner needs a hand, and being open enough to allow that to happen. Ramona only comes back to Scott after she figures this out, and together they can defeat impediments to their mutual happiness.

What’s great about Scott Pilgrim is that it turns its gaze resolutely outward. There are lots of other things going on in Scott Pilgrim besides what’s happening to Scott, and often, these are more important things. The central quest, Scott’s attempt to defeat Ramona’s seven evil exes (and, though we don’t realize it until the end, Ramona’s quest not to let that interference dissuade her from opening up to Scott, and to deal with Scott’s own romantic past), is a metaphor not only for the surprising and corrosive effects of your romantic past on your romantic present, but the ways in which pop-borne images of romance and conflict can get in the way of living a full life. The triumph at the end of the series is less that Scott and Ramona have defeated the final boss than that they have both seen these illusions as illusions (rendered in pixel art and textese) and are able to face each other as full, flawed human beings.

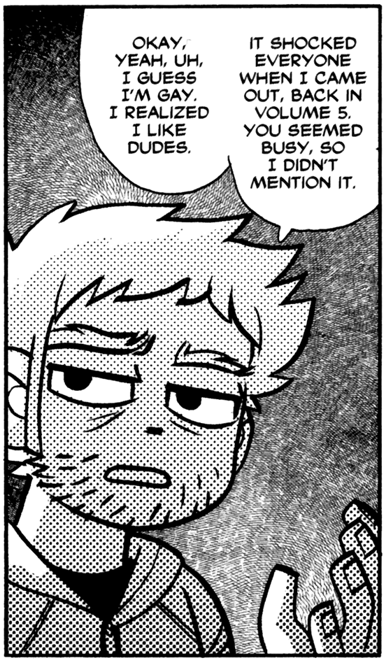

The problem with the movie is… well, in the simplest terms, it doesn’t pass the Bechdel test. For a movie based on an art comic, this is weird, to say the least. And it’s absolutely not true about the comic. One of the best things about it is that Scott often seems like a minor character in the context of his friends, all of whom are living much richer and fuller lives than he is. Female characters form friendships, male characters come out of the closet off-screen, and ex-girlfriends move on. The comic makes a joke about this: Scott’s self-centeredness causes him to assume, as fiction readers do, that nothing important happens without him around. But, of course, things do all the time.

They don’t, though, in the movie. Again, part of this is certainly structural. Movies just have less space available to them than do comics, and clearly they had to get through all seven exes. But that necessity spins out into other necessities: the main character has to be male, there has to be a clear romantic tension and resolution, there can’t be distractions from side characters. And though a lot of the great things about the comic are preserved, that sense of outward focus and of ladies existing without reference to dudes (or dudes without reference to ladies, honestly) absolutely vanishes.

I come here not to trash summer action movies; after all, I am probably going to go see The Expendables while my girlfriend is at a bridal shower I am confusingly not invited to. (I am thinking of it as my own little gender roles party!) But the process of adaptation has a way of revealing the essence of a medium. What Scott Pilgrim Vs. The World shows is just how small movies are.

Any narrative has to be cut to the bone; any visual element included for aesthetic purposes necessarily obscures a gesture or a shot that could have revealed something about character or context. And these huge differences between movies and comics speak back to Scott Pilgrim’s central message about the power of pop culture to shape our understanding of the world. Might someone whose reality has been shaped by the slower progression of a comic have less expectation of sudden, dramatic change than someone whose pop culture diet was primarily movies and goal-oriented video games? Scott and Ramona’s maturation mirrors the maturation of games themselves from simple 8-bit shooters to sprawling virtual worlds. The side-scrolling progression of the initial phase of their romance (go through each stage, beat the boss, go on to the next stage) turns out to be insufficient and unrewarding; it falls apart when faced with reality. So something new has to come along, something more like a sandbox game or an RPG where you’re free to explore and build up experience gradually before encountering big emotional moments on your own terms.

I’m not going to argue here that video games or comics contain more positive depictions of women than do movies, because that would be crazy. Rather: they could. Movies are old enough and big enough now that their artistic expectations have become indistinguishable from their technical features; somehow, the need to have a male protagonist is as unavoidable as keeping a film under two hours, or lining the sound up with the visuals. Games and comics are still relatively new, and relatively small, and still doing a lot of internal thinking about how they can and could work. As those get figured out, they’ll inevitably get wedded to aesthetic features, and harden into conventions that become self-reinforcing as audience expectation determines what will and won’t be rewarding. Scott Pilgrim represents one particular argument about how comics could work, and it’s an argument I like. But mostly, I like that it’s having this argument. That’s not really present in Scott Pilgrim the movie, and while I understand how that happens, and while I did enjoy it, I’m not entirely happy about it.

Editor’s Note: An earlier version of this column stated something really kind of hilarious, involving an invented heterosexual marriage of Dykes To Watch Out For author Bechdel. The copy desk regrets being really tired on a Friday afternoon. Our apologies.

Mike Barthel has written about pop music for a bunch of places, mostly Idolator and Flagpole, and is currently doing so for the Portland Mercury and Color magazine. He continues to have a Tumblr and be a grad student in Seattle.

Dreamcrasher, With Brady Hammock: I Spy Bill Cosby

by Brady Hammock

Every night millions of us interact with the rich and famous-in our dreams. But why should those celebrity encounters remain off the record? Star columnist Brady Hammock is here to bring you all the dirt about your favorite personalities and how they really act when they think they’re safe behind the scrim of your subconscious.

COZ FOR COMPLAINT?

Persistent Internet rumors notwithstanding, iconic entertainer and part-time culture grump Bill Cosby insists he is not dead. Maybe so. But why was Coz spotted in a recent dream skulking around rapping to a Tribe Called Quest jam in a Kansas City bar?

“He was semi-incognito in a ballcap and sunglasses,” reports our source, who reveals that the K.C. watering hole in the dream was called The Caddyshack. “He put a dollar into the juke box and played ‘Award Tour’ by A Tribe Called Quest, and started rapping along with it.”

What followed that early 1990s (somewhat profane!) classic on rappin’ Cosby’s playlist? The tipster can’t say for sure. “I woke up,” he explains. “But during my walk to work the next morning, I tried to do ‘Award Tour’ in a Cosby voice whenever I wasn’t in proximity to other pedestrians who might hear me.” Good idea. Now stop it.

YANKOVIC: HEARTBREAKER, DREAMTAKER

This may sound weird, but Al Yankovic turns out to be quite a pickup artist — not to mention a bit of a cad, according to a recent dream about the ’80s schlockmeister.

But how was the actual dream sex? Luckily our dreamer doesn’t recall! So read on!

“I was attending a Weird Al film festival, where they were showing Tapeheads,” this tipster relates — adding that the dimly remembered parodist confessed that he actually preferred that John Cusack/Tim Robbins vehicle to his own 1989 star turn in the lowbrow flop, UHF. Our source ended up “seated near Mr. Al,” soon they were chatting and engaging in a “ridiculous pantomime where I was trying to get past him … but somehow I ended up straddling his lap instead.”

So did they get their weird on? Well, the next thing our dreamer knows, it’s a few days later and “Mr. Al is telling me that the chemistry we seemed to have at the festival didn’t seem to translate to the bed, and he was sorry, but he didn’t want to see me anymore.” Oof — jilted by Weird Al! That sounds humiliating, but our source is philosophical.

“Since I didn’t seem to remember the sex part, I was OK with it,” she claims, “but still sad that I was not going to have a celebrity boyfriend.”

Celebrity boyfriend? Weren’t we just talking about Weird Al Yankovic? Wake up!

NOT SO KEEN ON DR. KEENER

Catherine Keener has snagged Oscar noms for her roles in Being John Malkovich and Capote — but a reliable source has dreamed that she’s also his dermatologist, and he was not impressed with her performance.

“She was digging around in my scalp and telling me in no uncertain terms how DISGUSTING it was,” complains our tipster. “She kept picking at the back of my head with a long fingernail. At one point she said to me, ‘you know there’s a hole back here, right?’”

How rude! Yet this dreamer seems to hold no grudge: “Basically she acted exactly like you would expect Catherine Keener to act. If she was a dermatologist. And you had psoriasis.”

WHAM, BAM!

A tipster with impeccable presidential-dream credentials (“I dream did-it with Clinton TWICE,” she notes; “once in a New York City subway station where he was holding a book club”) has just come forward with the shocking story of a 2008 dream concerning Barack Obama.

In her dream, our saucy source was swept up by the “big moment” when Obama won the North Carolina primary, and headed straight for the campaign’s state headquarters “to congratulate him.”

“The ‘headquarters’ was a double-wide in some kind of grassy marsh, through which I had to wade,” this dreamer continues. “He was there all alone, and he was sitting down with his legs extended like Jimmy Stewart in Rear Window, only he was wearing more of a full-body cast, not just a leg cast.”

But that (somehow) didn’t stop the prez-to-be from engaging in a “really great” hug. “But then he held on for an unnecessarily long time,” the dreaming temptress reveals. Message: Yes We Can! “I remember thinking ‘uh-oh, he doesn’t know where to draw the line.’ We were both enjoying the squeeze, and I’m not saying I wanted to let go, but he should have kept it professional. Shocking, right?!”

Hm. Not with dream constituents like you around it isn’t!

Have you slumbered around with a star? What popular singer surprised you in your dream by becoming your high school algebra teacher? Brady Hammock wants to share your story with the world. Tattle your tale-or as much of it as you can remember-here. Confidentiality GUARANTEED! Pleasant dreams!

Slutty Oysters Spreading Herpes Throughout Extra-Hot Bivalve Beds

Slutty Oysters Spreading Herpes Throughout Extra-Hot Bivalve Beds

“A virulent form of herpes is killing countless Pacific oysters this summer, according to a new study accepted for publication in the journal Virus Research. The deadly virus has already destroyed anywhere from 20 to 100 percent of its victims in French oyster beds, and has spread to oysters in Britain.”

–First Rome. Now, oysters. Discovery reports more bad news about global warming.

Forceful Conduct: The Anthony Graber Case

by Sutton Stokes

Earlier this year, a man named Anthony Graber was breaking the law on his sport bike (allegedly, etc.) along a stretch of Interstate 95 in Maryland, helmet cam rolling. Graber later posted the resulting video to YouTube, so anybody who wants to can watch him weave in and out of traffic, steer one-handed, and supposedly pop a wheelie.

About three minutes into the video, Graber turns his head and the camera catches a gray sedan about fifty yards behind him.

A few seconds later, Graber slows to a stop in a traffic line on an exit ramp. There, at about minute 3:10, the gray sedan noses into and blocks his lane.

The sedan’s door flies open and a man with a distinct resemblance to Pee Wee Herman, but wearing jeans and a fleece pullover, jumps out and rushes toward Graver.

The man is holding a gun and yelling “get off the motorcycle.”

The man with the gun yells “get off the motorcycle” a total of three times before he adds “state police.”

Graber departed that encounter with nothing more than a speeding citation; his real trouble started when he published the video. A county prosecutor decided to charge him with violating the Maryland Wiretap Act, for which he could be sentenced to as many as sixteen years in prison.

He probably won’t be. In July, the Maryland Office of the Attorney General called bullshit, sharing its opinion that, essentially, what’s good for the goose is good for the gander: under Maryland law, private citizens have just as much right to record traffic stops as police do (PDF). But the AG’s opinion is advisory and non-binding; it’s still up to the Harford County prosecutor whether the case will proceed to trial, and people have been convicted on similar charges in other states.

Graber’s experience has excited a lot of interest nationwide. A man named Carlos Miller, who runs the blog Photography is Not a Crime, has been following Graber’s case closely, and Time just joined the party with an August 4th article by one Adam Cohen that ran under the headline “Should Videotaping the Police Really Be a Crime?”

Perhaps not surprisingly, Cohen concludes that, no, it shouldn’t: “If the police are doing their jobs properly, they should have nothing to worry about.”

I see the logic behind what he’s saying. And I don’t disagree with the idea that members of a free society should damn well be able to videotape the people they commission to enforce laws behind badges and guns. And yes, we must therefore resist what seems to be a rising tide of police resistance to being videotaped.

But we might as well try to understand why police don’t like to be videotaped, and it’s not necessarily because they fear losing the impunity to misbehave, which is what I take Cohen to be implying.

It could also be because, even when “police are doing their jobs properly,” it often doesn’t look like they are. Not to the untrained observer, anyway.

* * *

Back in my use-of-force class at the U.S. Coast Guard’s Maritime Law Enforcement school, the instructor-who, judging by the number of pushups he made us do, was not at all tolerant of the possibility that we might do our jobs the slightest bit improperly-was firmly of the opinion that videotaping might give us something to worry about.

He unequivocally told us never to bring a camera along on a boarding.

The Coast Guard doesn’t have anything like dashboard cams yet, and we should count ourselves lucky, he told us.

Law enforcement just doesn’t look right to civilians, even if you are doing everything exactly the way the way you have been trained to do it.

In the ensuing years, I’ve had countless opportunities to reflect on just how right he was.

You have only to glance, for example, at the photograph that Gizmodo chose to illustrate its own recent post on the increasing use of cameras “to depict police abuse,” including in the Graber case.

In the photo, not one but two police officers have their knees on someone’s back, pressing him face-first into the concrete as they cuff him. And how is that fair?

Clearly, this is a prima facie example of “police abuse.”

Except no, it’s not.

Without knowing more about the events that led up to the scene in that photo, all we can say is that it shows two police officers trying to handcuff someone who doesn’t want to be handcuffed. Handcuffs are tiny-pretty much exactly wrist-sized, for obvious reasons-so if the person you are trying to cuff is moving his wrists around even a little, you aren’t going to prevail without either a very uneven struggle (at least two against one, preferably three) or, if you are alone, without inflicting enough pain to get your “subject” to see things your way.

Combine that with 1. the way even the most mild-mannered people can react to the feel of actual cold steel locking closed on their wrists and 2. the fact that the moment of cuffing is one of the most dangerous for police, because they have to get inside arm’s reach of someone who is probably not very thrilled with them-and you may start to understand why police can assume such a dominant posture when it comes time to put on the bracelets.

And while many police may be trained-as I was-to handle “passive” and “active” resistance differently, the bar for “active” is low: simply trying to tug your arm away from a cop who has grabbed it can be an express ticket straight past “commands and consequences” to some decidedly less pleasant locations on the “use of force continuum.”

Which gets back to what my instructor was saying. The cops in that photo may be doing exactly what they’ve been trained to do, maximizing their own safety and minimizing the chances of the arrestee getting a broken wrist. (Without more context, we can’t eliminate the possibility that they might coincidentally also be assholes, of course. Some cops are. So are some bus drivers and senators.)

To the casual observer, though, it looks like this: an arrestee who wasn’t “struggling” and didn’t even throw a punch is suddenly in the middle of a three-cop pile-on, and it just doesn’t look right.

* * *

Then again, sometimes videos do capture cops doing their jobs improperly, which seems to be the case in the Graber video.

Aside from the question of pulling a gun on a speeder-we were trained that, if you think you need your gun out, you need your gun out-it certainly seems like a problem that this cop both has his gun out and says three complete sentences to Graber before identifying himself as a police officer.

It also seems like a big problem that he never shows a badge at all.

Look at the expression on the cop’s face as he puts his gun away, seemingly upon noticing the arrival of the marked cruiser that becomes visible later when Graber dismounts. Who can say what he’s thinking, but if I had to make a wager, it wouldn’t be that he is confident that he is entirely in the right.

For that matter, it is interesting to consider the fact that, while the existence of Graber’s camera is still a secret at this point, the cop knows he is downrange of the one on the uniform’s dashboard. Is he already thinking about videos and whether or not he is ready for his closeup?

Anyway, I failed my first use-of-force practical exam for pretty much the exact same mistake this trooper made-not explaining quickly and clearly who the hell he is and why anyone should do anything other than run away from or preemptively open fire on the road rager with the gun. I think Graber’s video could have a second, more fruitful life as an illustration to academy cadets of what not to do in similar situations.

Of course, the video is already out; whatever damage it can do has been done. The target of the Graber prosecution isn’t Graber-it’s all of the people who might think of making their own video later. It’s hard to avoid concluding that the authorities want to inspire the following thought before anyone else decides to hit the red button: “Yes, the charges may eventually be dropped, but is it really worth the hassle?”

You really have to like the taste of your master’s boot leather for the answer to that question to be anything but “yes,” but then that’s easy to say from the safety of my laptop. Here’s hoping that at least some of us continue to find the courage of our convictions when it actually matters. Just because some cops have some relatively good reasons for preferring not to be videotaped doesn’t mean the rest of us have to care.

Sutton Stokes will certainly record any encounters he has with the West Virginia State Police.

Vampire Bats Bring Nightmare (And Blockbuster) To Life In Peru

“The rise in vampire attacks has baffled the people of the region, but some experts have linked mass vampire bat attacks to deforestation in the Amazon. Vampire bats normally feed on wildlife or livestock, drinking their blood while they sleep. But they turn to humans for food when their natural food chain is jeopardized, particularly in areas where rainforest habitat has been destroyed. Some locals have also suggested that this latest outbreak may be linked to the unusually low temperatures the Peru this year.”

-In what must be a very truly terrifying episode for the Awajun Indians, vampire bats have recently attacked more than 500 people in the Urakusa region of northwestern Peru. But, come on, like authorities really don’t know what’s going on.

Hey You! Send a Photographer to Afghanistan!

Conceptual photographer Nicholas Grider has started a Kickstarter project to embed in Afghanistan. Grider has extensively photographed “Fake Afghanistan”-the training sites in the U.S. for Marines-and now he wants to photograph the real one. (The “real” one?) Give a little!

The Smoking Police Strike Again

New York City is now cracking down outdoor smoking areas at bars, which are required to be clearly marked, “no more than 25% of the outdoor seating capacity,” and “at least 3 feet away from the non-smoking area.” Pretty soon the only place you will be allowed to smoke in this town is on my fire escape. Bring some bourbon with you and I’ll make sure you get one of the good slats near the window.

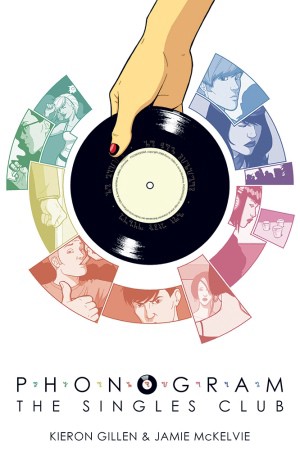

Enthusiasms: 'The Singles Club'

by Sarah Jaffe

Phonogram is a comic about how music is magic. Literally. There are two volumes now: the first, Rue Britannia, about the death of and nostalgia for Britpop, and, more recently, The Singles Club.

Set in a British nightclub, each single issue of The Singles Club focuses on one person, one experience of the same night, which is both an ordinary night in a club and somehow extraordinary for each of them. Each single issue here is a complete story, based loosely around a song-the “Singles” of the title-and what that song means. Each one is a slightly different capital-M Metaphor for what pop music really does to us. Music affects each character in a different way-most of them are “Phonomancers”; in the world of the comic, they’re magicians who use pop songs to create their magic.

The nightclub has three rules: No Male Singers, You Must Dance, and No Magic. Of course all of those rules are broken, but particularly the third one, since magic here is not only something that the characters do but something that happens to them. The magic in pop songs is never quite under their control. And it veers here between Metaphor and actual fact.

The single issue has been ripe for comics creators to play with in recent years, and writer Kieron Gillen and artist Jamie McKelvie had fun with it in these books, but reading them all through together in collected form in The Singles Club trade has its own pleasure. The stories build one upon the next, intertwining around one another like bodies on a dancefloor, so that the whole comic is not just about the love of dancing but is itself a dance-a dance of characters and narratives, of art and words, of meaning and layers and feelings and memories.

Phonogram is part of a loose group of books that I recommend to my non-comics friends as much as my comics friends. Because we are a different breed, us comics folks, we like our pop culture a little madder than most. So many of the books usually recommended to non-comics fans, though, are autobiography spilled beautifully onto a page with liberal helpings of narration, text to help along the non-comics fan, unused to reading pictures for a story, tracing narrative between panels. But Phonogram isn’t one of those comics-it needs no narration even when it has it, and it’s told as much in moods and feelings-like a pop song-as in a story.

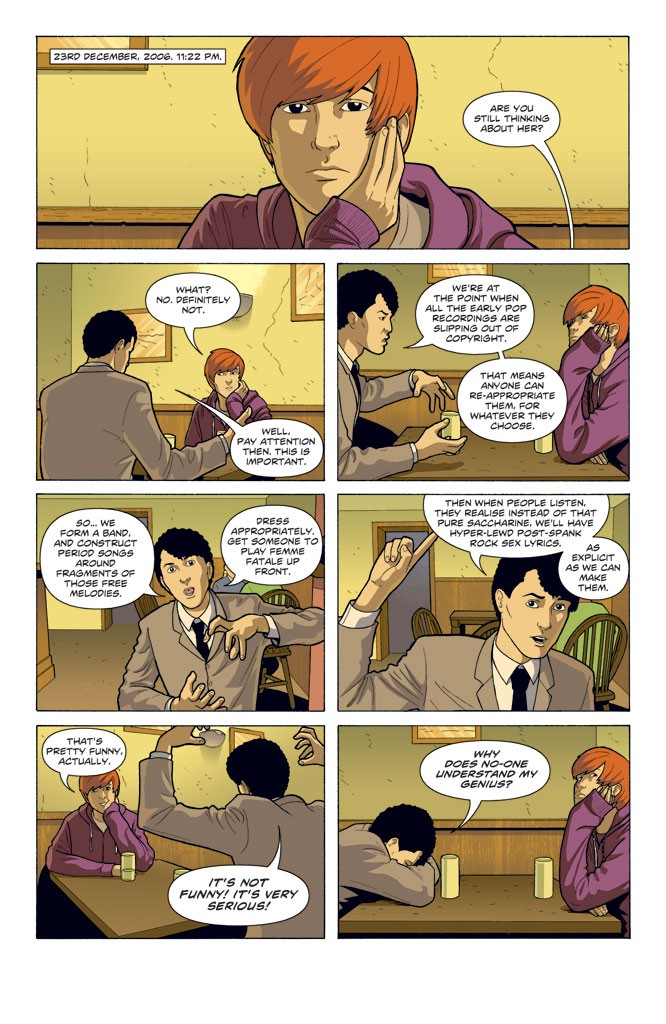

Gillen himself has written about the need to split comics into Art and Story, and why it’s wrong, why comics are more than illustrated prose:

[C]omic reviewers — especially mainstream comic reviewers — tend to dissect art and writing separately, and credit all praise or hatred at the artist or writer respectively…. Which of course, is fair. Their names are on the book, after all. But on another level, it’s totally delusional…..We push and pull one another, and the work which comes out the other end is some strange alloy of our skills, desires and ability to give a toss on any given day… The closest parallel is bands, the other small groups of impassioned individuals gathered together for a larger purpose whose work — even the work which can be clearly originated by one member of the collective — is best analysed as part of the whole.

The best comics don’t allow you to split them apart this way. They carry you along in words and pictures, creating a work that is more than the sum of its parts. Phonogram’s closest companions in the medium are hard to figure out-it has more in common with Scott Pilgrim on one hand or Demo on the other than mainstream comics, though Gillen and McKelvie both have worked on plenty of superhero books. But you don’t need to be a comics person at all to love Phonogram. You just have to enjoy the ride as if it’s the moment watching two people dancing in a blur where you can’t tell which one is which. Or, as the writer himself says (though he and I would probably agree that you should never read a book the way the authors tell you), like a band. Ultimately the dance is what’s worth it.

Comics suffer from the assumption that they are for kids, and that they are not serious. Phonogram glories in not-being-serious and by not being serious-and poking at the layers of seriousness put on by kids-it gets to places that make you feel something. Even if it’s just seriously the need to go dancing. (Go ahead and go. Come back later. We’ll understand.)

In getting at why music is magic it makes an argument for all pop culture, for things that we assume are transient, whether that’s a chart-topping single or youth, sex, heartbreak, a glance across a room or the moment that just the right song hits your ears and you hit the dancefloor and just can’t pretend for one more second that you’re too cool.

Penny is the Phonogram character

who does not just love dancing but personifies it. Her issue begins the series in her own candy-blonde perfect argument for momentary bliss being worth it, every time. Penny (dancing) is a lightning rod and a Rorschach test for the other characters-do they love her, envy her, hate her, ignore her? All the other characters’ feelings toward Penny are their feelings toward the world, their feelings about life.

Penny’s physicality jumps off the page and makes you wish just for a second for the power of cinema to see her move, even though this is the most kinetic I’ve ever seen still pictures. And anyway, you know how she moves, don’t you? You’ve all seen that girl in a club who just doesn’t give a fuck and dances wildly enough to knock the cobwebs off that cliche about dancing like no one’s watching. Penny talks plenty, too, straight to camera (so to speak) but, like Rita Hayworth in the classic Gilda, she can talk and dance at the same time.

Marc comes next, all stillness where Penny is all motion-Marc is stuck in the past and not even Penny’s wild blur can drag him out. But he’s the prettiest thing you’ve ever seen, oh yeah, every guy who’s ever leaned against a wall and been just cool enough doing it that you want to, need to make him move. That he holds your attention by staying there and you can feel his stillness even as you dance. Is he watching you? He’s Jordan Catalano-”I love the way he leans. Like, against things.”

It’s a metaphor for Marc’s whole life-his friendships, relationships and loves happen to him. Other characters have “Phonomancer” names they’ve made up; Marc’s was given to him and he shifts uneasily when the others use it on him. He’s got a pretty boy’s self-pity and self-absorption but for all that a universal problem.

He got his heart broken to the tune of, well, we don’t quite know. All we know is that the song comes on in the club and takes him back into a memory. While the comics are full of songs that we all know, this one is intentionally left out so you can insert your own curse song here, the one that doesn’t just remind you but carries you straight back to that moment that still stabs you in the guts. Because pain can be an old friend just like a song, after all.

“She,” the girl who broke Marc’s heart, doesn’t have a name and that’s usually a bad sign for a character-Token Girl time. But even the “she” in Marc’s head won’t let him blame her for his self-pity and so instead we get the best feminist twist on the Manic Pixie Dream Girl ever. Even though she’s just a memory she calls Marc on his shit, and gives him permission to hurt at the same time. She makes him acknowledge just how much of her he’s made up. No, she’s not real, but our exes never really are.

While Marc clings to his solipsism-”I hurt, therefore I am”-Emily Aster wields the past like a double-edged knife and knows that it’ll cut her. She’s willing to bleed so long as no one sees her flinch, like Tom Waits’ “Romeo is Bleeding” propping himself up so tough. Fittingly her song is by the Knife but when she gets to hear it she’s slipped into her own cursed past and can’t dance properly to it, stumbling over the words and steps. Except Emily knows quite well she cursed herself.

Emily reinvented herself in sharp pain on skin, new clothes and a sleek haircut, selfish sex and plenty of magic. She’s cold and harsh and brittle and yes, strong in her own way and I see myself in her. In both her mirror images, reflecting their hate back at one another in the best panel in the entire comic. Pressed against a mirror giving her old self in the reflection the finger, in the arms of a boy she’ll hatefuck to prove something to her old self-mostly that she’s not her.

The Singles Club is seven issues long and so right in the middle we stop and focus on the DJ booth. On Seth Bingo and Silent Girl, who have created the club night around which the rest of the characters orbit. It’s like watching the pilots of this story for a while, and it’s conceptually the most interesting even though visually the most static. The panels don’t change, like a camera set just to catch what the DJs are up to, and it’s mostly a showcase of how Silent Girl is not actually silent at all. (Once again, the clever Team Phonogram prove their cred as two of the most feminist guys in comics.)

She’s no foil, but instead the only one in the room who really gets it, who really hasn’t put her love for music under a pile of pretensions or fears. Seth wants to ban people from using magic in his club so that he can be the only one wielding it, but Silent Girl gets the best line in the book with “You’re not my vinyl Moses,” reminding Seth why they are there. The visual of the two of them tearing apart the panel to blast the dancefloor with pure pop and all the magic that contains is brilliant. Brilliant.

It acknowledges the parts of the story that are missing in all comics, the things just outside panel borders, and then breaks down those walls. And the double-page spread that follows pulls in all the characters in one of those perfect nightclub moments where everyone is dancing. The one rule that doesn’t get broken: You Must Dance.

We need all the up of “Konichiwa, Bitches” and Seth and Silent to carry us through Laura, though, because Laura’s hurt and need is so close to the surface that she can only cover it up with massive doses of Long Blondes lyrics. Oh yeah, Laura isn’t happy or pretty or going to find an easy solution. She doesn’t even know which solution she wants to find, doesn’t know hate from love, lust from envy. She’s well on her way to being Emily yet she doesn’t even have the wherewithal to create herself a new identity that hasn’t been forged for her-you can’t steal the persona a pop star’s already created without just coming across as ridiculous. Emily looks away from the mirror and doesn’t like the mirror that Laura holds up to her, either.

Yet it’s for Laura that Emily does the one thing all night that might be considered kind, and that itself tells you as much about Laura as it does about Emily. We feel bad for the people who remind us of ourselves. We also hurt the things in ourselves that we see in others. Every minute. Even Emily. Even Laura. Which is why Lloyd and Laura have to cross paths, and have to repel like two magnets wrong side out. The attraction could be there, it could make sense, but not from this side.

Laura has to escape by learning to walk the line between being cruel to others and honest with herself and just maybe there’s more hope for her than Emily, even, as she makes her break, alone, at the end of the night. Most of the Singles Club characters end up finding their solutions alone (the double play of the title-single tracks, single-issue comics that don’t require being read together but play so much better when they are, and single people figuring out that that’s OK). Nobody finds salvation in another person, here. Which makes sense in a way because you can’t share a comic the same way as a piece of music, pressed body to body in a crowded, too-loud room. And this is a story that despite being loaded with music and motion needed to be told in comics.

And then Lloyd. Lloyd and Laura need each other and need to reject each other. Lloyd is as much a construction as Laura but where Laura wants to be something, Lloyd wants to make something. He’s angry that no one calls him by his Phonomancer name, the person he’s created, and more angry that no one cares about his brilliant idea. Lloyd’s story is the only one that mostly takes place outside of the club. No, he’s too serious to dance, so he goes home and makes: A ZINE. And Phonogram flirts with fanzine culture to begin with, to the point of the back pages in the single issues being stocked with interviews and rumination on bands, not to mention a song list and notes on all the bands mentioned-and then of course the wonderful Matt Sheret created a zine ABOUT Phonogram, and now this issue of The Singles Club more or less is a zine. But still a comic. If that makes you feel better.

“Wolf Like Me” and Kid-With-Knife end the series and while each comic here is a pop song, a few minutes of entertainment and bliss in a compact package made as pretty as possible for you to love, cry to, and refer to forever, well, this one takes that metaphor and explodes it right in front of you. Oh, you thought the previous issues were perfect singles? Here you go. The issue reads along exactly with the song. The perfect single, indeed.

It’s also the issue that brilliantly captures the populism in pop. You don’t need a fancy grimoire to unlock the magic in a pop song. You just have to feel it. Silent Girl knows this but it is her job, with Seth, to control the secrets and command the room. And David Kohl, the godfather of The Singles Club, the star of Rue Britannia, knows it too and tells Kid-With-Knife, who is the furthest thing from the rest of these hipsleek indie kids, how to do it. “That’s it?”

Start the track, the bleeding-brilliant TV on the Radio record, when Kid realizes it. Realize that this song is shattering the rule against male singers. Realize that somewhere in here this pure-male energy is going to crash into someone else. Take bets on who it is. You may be right. Either way, you’ll love it.

It’s the closest thing to a superhero story in Phonogram and you can feel the rhythm pulsing through each page, each punch, each step. It’s thrilling. It’s magic. He gets it.

The magic isn’t just in the music, really. It’s in all of us. It’s what we add to it. It’s what makes it matter. There’s as much magic in a few words in an email that make it all a little better as on a dancefloor-it’s just a different kind. There’s magic in a first kiss in an alley as much as there is when just the right song is playing.

The magic in the music is what we put into it as much as anything else. And so you don’t need to have a sleek haircut or recognize all these songs (though if you want a tracklist, Kieron Gillen has provided one) or even love comics normally to love this collection. It is what you see in it. As all art should be.

Sarah Jaffe is the Web Ninja at GRITtv with Laura Flanders and Deputy Editor of GlobalComment.com.