I Was Briefly the Face of an Unemployed Generation

by Emma Carmichael

Three months ago, I posed for my college graduation photo — the official one in front of an American flag, diploma in hand, ready to face the world. Since then the photography company has emailed me almost weekly, offering discount upon discount and before-it’s-too-lates. But when the picture was taken, just seconds after I had crossed the stage and shaken hands, I was too delirious to smile, so instead I bit my lower lip. I mean I almost swallowed it. I don’t know how it happened. Normally, I have no trouble smiling. But I remember at that moment that the muscles would not contract into a casual, triumphant smile, that my lower jaw was literally shaking with some kind of dread or excitement or panic or all of those things, and to control it — literally, to stop the shaking — I bit my lower lip. In a big way. The photo is commendably awful. If the discount gets steep enough then I’ll buy it and take it out whenever I need to take myself less seriously.

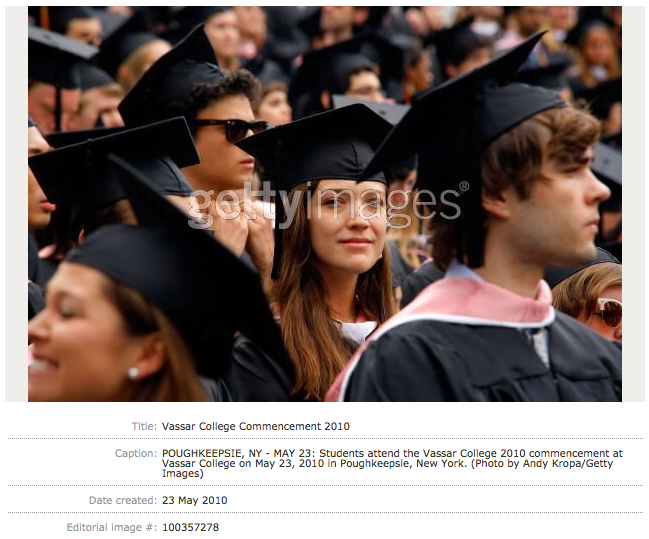

But another photo of me on graduation day — May 23, 2010 — was, in conventional modern Internet terms, a huge success.

There was a moment on the day I graduated when, bored by the endless procession and also nursing a pulsing hangover, I looked away from the crowd — basically at nothing. It was at this moment that a photographer seemed to spring into my line of vision, and I heard a snap, and I broke my gaze to catch him darting away again. I was vaguely aware that he had taken my photo. I was more aware that I was wearing a polyester black gown in ninety-degree heat at ten in the morning.

A few days later that photo showed up on the Internet on a popular news blog. It was credited as a Getty image. A lot of people sent me the link. The photo was unexpected for a number of reasons; most disturbingly, in that bored, brain-pounding moment when I glanced mindlessly at the five-piece brass band playing the processional, I had somehow managed to look thoughtful. I am looking away from the crowd, away from my classmates who face forward and smile and rejoice in the moment, and I am looking somehow self-satisfied and also positively uncertain of myself. I also look tired. Worn-down. As if I’ve had enough.

Is there anything more pathetic than unintentional poignancy?

After that first posting, the photo continued to surface, mostly in a handful of articles about the recently graduated class of two thousand and ten. The articles were all about how nobody in this graduating class would get hired for a long time. CNN reported it. The Atlantic reported it. The Huffington Post reported it. We were all destined for unemployment and my face seemed to say it best. Hungover and under-prepared, but I could fake contemplation and self-awareness with the best of them.

My friends declared me The Face of An Unemployed Generation. I received emails with links embedded, a quick note attached: “Hey Emma, you’re famous! Hired yet?” It was fine; it was funny. My father tracked down the photographer who took it, the springy guy, and talked him into mailing us a few copies without the expensive Getty costs. My grandmothers were thrilled.

The Getty photo has now made it to my parents’ piano top, suggesting that is somehow iconic, affecting. It’s not right. The iconic photos I know best — my parents wrapped in a blanket on a porch in Vermont at age 22, laughing and hugging and dotted with sunlight — are from a time when film was developed and intensely personal and usually in black and white. This picture, the brass-band gaze picture, is hyper-modern. It is digital, high-quality, licensed, recycled, stock, somehow representative. And most of all, a fluke.

The image that really has stuck is not even necessarily one of me, but of many others-the same way my parents on a porch in the seventies is probably the image many of my classmates have of their parents on a porch in the seventies.

In the two-week waiting period after my very first job interview after graduation — a period in which I over-analyzed my every misplaced word and nostril-scratch — I remembered with a terrified jolt that before it had even begun, before I had crossed my legs and folded my hands in my lap and smiled expectantly across a desk with neatly stacked papers, the very first image I gave a potential employer was of me, pulling on a pair of locked glass doors.

I was wearing safety-pinned pencil skirt and a borrowed blazer and I had three copies of my resume in the canvas bag on my shoulder. The woman at the elevator bank twenty floors down had wished me good luck and told me I’d do fine.

I got off the elevator on the twentieth floor of the Manhattan skyscraper, I walked to the doors, and I pulled. Then, I pushed. The doors did not move. The man in the suit came forward from where he stood waiting for me, beyond the doors, and opened them. Of course. The doors to corporate America were locked, and I could not get in. I am the cliché in action.

When I reached out to shake the man’s hand and smile confidently — I know that I bit my lip. Click.

And you know the first thing he said to me? “You look so familiar.”

Emma is moving from Vermont to Brooklyn to better blend in with the rest of her unemployed peers. She sort of wishes she were on Twitter.

The photo of Emma Carmichael above is by Andy Kropa, licensed through Getty Images.

We Can See the Reputation Market's Event Horizon From Here

The future of personal branding can be viewed quite darkly. In that future, you will be crushed by the banality of your own self-promotion. But here’s a question-what if the phenomena of endless marketing of your own personal self persists, and is not a VC flash in the pan, a burp on the road to SkyNet? Are you sufficiently personally branded? Will you be left behind?

Well, yes. You will be left behind. The Reputation Economy is soon to become less conjecture and more pain in the ass. Which means that the Whuffie Event Horizon is upon us. But it’s not too late to at least look busy.

That’s some scary jargon. Even “economy” is foreboding, and it’s more ominous to see the organizing principles of the movements of capital and labor applied to what other people think of you. It’s not really economics per se-it’s a high tech collision between two of the greatest scientific advances of the 20th century, marketing and publicity, a collision that paratroops into an economic context.

Imagine that “good will” was something that could be held and hugged and thrown at hobos. That’s the Reputation Economy. Your good will, the collection of positive associations that is associated with your name and person, becomes a commodity. Not that you can sell it (yet), but it is a short-hand for social standing, or leverage. Maybe once you tucked away a favor owed, so you didn’t waste it on something stupid. Now then imagine that as the rule and not the exception. And automated. And inevitable.

And the quantification of this Reputation we will call Whuffie, which was coined by novelist/Boinger Cory Doctorow in his 2003 novel Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom. In the book, Whuffie is monitored, by technological means, and is an actual replacement for dollar bills. Doctorow posits a future cashless society in which free market precepts are obviated by a lack of scarcity of resources. Without scarcity, without the concept of a “buyer,” trade is conducted on the basis of accumulated good will. Not that that exact scenario is going to happen anytime soon, but Whuffie is a convenient and silly handle. All the nice things said about you, all the versions of third party approval social media provides, all the happy ripples thrown out by your very good reputation interfacing with the world-Whuffie.

So what to do? The path of least resistance is to submit. How many hours are there in the day? Exactly as many hours a day you need to spend updating, creating sticky personal content, inventing neologisms, propagating memes and generally hoarding your Whuffie. Times are tight right now, but who can accurately predict the tightness to come? And will you have enough Whuffie to lubricate yourself through tighter times? You think you know the answer to that question. You don’t. The answer is: you never have enough Whuffie, ever, and you will always need more. You are not Cory Doctorow. Your Whuffie is a finite resource. It’s no more difficult than devoting near-constant attention to an every-changing array of platforms and apps, and, on top of that, knowing when to jump into a specific pool (early) and when to hop out (a microsecond before it gets MySpaced). It is daunting, but you will have plenty of company, and you will spend your time wondering if this company has duly accepted you as a fellow Whuffie-miner. That should be comforting in its recursiveness, but comfort is not a commodity. Like Whuffie.

Alarmist? Well, in the sense that an alarm is being sounded. Panicking is your own problem, but remember that time panicking will detract from your time branding, unless you manage to make a post/Tweet/update out of it.

And check in! Don’t forget to check in, be it Foursquare, Gowalla, Facebook Places and whatever succeeds them. What’s the point of having everyone know what you’re doing if they don’t know where you are? Imagine all the places you could be the Mayor of-Dinghy Dogs! The Mall of America! The Missouri Department of Natural Resources! The Trump Whatever! It seems a bit stalky, but how can it really be stalky if you are advertising where you are? A stalker of your own would be a badge of honor. And just think of it as a harmless geolocative application, a superimposition of the Net onto real space, and not yet another retreat into high school social dynamics. It’s a lot less threatening, and a lot more William Gibson, that way. But get to it, before all the other social apps integrate a locative functionality, because you don’t want to be a late adapter. (Which is about the same thing as being an inappropriate-toucher, as far as the RE goes.)

Some of you may have a name that is either shared by many or shared by someone already occupying a portion of public space. (Google me if you’d like to learn about the Yankees farm system.) This is not fair. You didn’t get to pick your own name, after all. Why should you be Whuffie-challenged because of marketplace confusion.

Solution? Pick a new name. True, only the flaky did that, back in the day, but that was before all these ones and zeros were flying around through the ethers, and so adapt now and let everyone else wonder what flaky used to mean. And take a cue from intellectual property management, since it’s an adjacent field to this RE, and make up your new name from nothing, giving it distinctness and preeminent SEO. Rappers have been doing it for a decade, as have pharmaceuticals. Failing that, rip something out of context. The world might need a graphics designer named “Xantham,” a human resources manager named “C-clamp,” or even an acquisitions librarian named “So Long And Thanks For All The Fish.”

And if this all seems too much work, and does not pass the cost-benefit analysis, you can Pynchon it. Or, as they say, “IRL” it. Be excellent, succeed in your field and let your success be your team of bodyguards. Go off-grid, erase every last vestige of your footprint (minus a yearbook photo or two), be quiet and enjoy whatever it is that anonymous people enjoy-family? Friends? Rhubarb pie? You will not be able to derive the benefit of the RE grab-ass, of the minute-by-minute liked/not-liked, but then again you will enjoy the freedom from all that. If there is a downside, it is that you have to be actually talented, as this kind of success cannot be faked, or seduced with intrinsic popularity. Then again, there’s no quicker way to find out.

But before we load up the storm cellar with canned goods and cute animal videos, is it possible to stop this approach of the Whuffie Event Horizon, to forestall this creeping menace? No. Sorry. And you’d surmise that the reason why we can’t avoid this is technology, and its tendency to not only advance but to fill any negative space as it does.

But technology is just a precondition; it’s the sky being blue. What powers the WEH to the point of imminence is in fact us, all of us, and our exceptionalism, our post-modern vanity, which is no longer a privilege but a right. At some point after the Baby Boom, maybe when they were ripping the jungle gyms out of playgrounds and ramping up production on child safety helmets, every single person became suddenly destined. We were not going to have a quiet life working down at the plant, putting the kids through college, maybe buying a boat or an Italian espresso machine. We were going to accomplish something. We were going to stand out. So now that we are all destined to be superlative, organizing the systems of how we stand out will crystallize.

This is not necessarily a fame instinct, though that is rampant too. This is more of a public-sphere instinct. This is taking what used to be one’s affinity group and blowing it out. It’s not exhibitionism. It’s amplification. It’s a novel way that friends are now made. And since it’s not going anywhere, we are staring into the business end of the WEH.

What are your chances? Very good. You are exceptional. Sadly, for everyone else, it’s looking pretty bleak. Whuffie’s got to come from somewhere, and the magnitude of your personal achievement will suck all the air out of the room, creating a vacuum in which the flame of everyone else’s awesome will not burn. It’s a good thing you’re you, and not them.

The odd aspect of the choice of the term “Whuffie” is that, going back to Doctorow, in the world he created where abundance has leveraged capitalism into something new, death has also been defeated. Take a dirt nap and you are rebooted. This is a condition that does not exist now, so maybe it’s spurious to superimpose Whuffie over current times. Or maybe mortality is the enabling condition of the RE, since Reputation is just really a low-bandwidth version of immortality-and we’ve finally found an ingenious way to commodify it.

Brent Cox is a writer living in Brooklyn, NY.

Using Math to Judge the Stupidity (and Deadliness) of Crowds

How to stay alive when a crowd turns crushy: “Think of a crowd of people like a wave pool, where choppy waters represent crush conditions. When individuals are facing in similar directions to their neighbors, the crowd moves together-much like a single wave moving through the pool. But if people move in different directions they start pushing against each other, and that’s when things get choppy. So by detecting when movements in the crowd start to fall out of sync, the researchers can predict the development of dangerous conditions.”

Fewer People Dying At, Going To, Work

The bright side of unemployment: “According to new data unveiled by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics last week, there were 4,430 workplace fatalities last year compared with 5,214 in 2008. While firms in America’s most dangerous industries would love to toast a triumph of workplace safety in the 21st century, there’s no escaping the fact that fewer jobs, in general, existed last year.”

Pope Knows All About What They Get Up To On Knifecrime Island

You’ll enjoy this: “Pilgrims attending the large public events during Pope Benedict’s visit to England and Scotland next month have been issued a long list of do’s and don’ts including a ban on musical instruments and”-wait for it, wait for it… okay, here it comes-”steel cutlery.” So very satisfying!

Happy Monday, Shaun Ryder

“Chants of ‘Who are you?’ were met with confusion by Ryder, who thought the crowd were chanting for fellow Manchester band New Order. After some bottle-throwing and abuse from the crowd, they were treated to a series of unwanted Happy Mondays and Black Grape covers from Ryder and band including ‘Kinky Afro’, ‘Reverend Black Grape’ and ‘Hallelujah’. After calling an abusive member of the crowd ‘a f**king knob’, Ryder played ‘Step On’ before leaving the stage.”

-Shaun William Ryder was nearly bottled offstage this weekend after confused fans at Britain’s V Festival turned up expecting Peter Andre (a singer known for having been married to something called Jordan) to perform instead. Shaun Ryder turns 48-!!!-today.

Whyever Are People Being Mean To Real Estate Brokers?

Residential brokers in New York City complain: people who buy apartments are jerks! Pushy, demanding, rude jerks. I mean, this we already knew mostly. (Though also: “One broker who complained to this reporter about a demanding client provided e-mails that showed her own comments were actually more hostile.”)

Why We Cry

Why do we cry? To get attention, to get what we want, or to get away with something bad we did. And also because it might make us feel better.

In Fear Of Fear

As jobless claims continue to spiral, and desperate Americans start ransacking their retirement accounts for sustenance, the US economy looks like it’s developed much the same allergy to productive labor that’s long afflicted the Kardashian clan. And now comes Washington Post business writer Neil Irwin to observe that employers aren’t adding jobs-even with corporate profits increasing-for a simple reason: They aren’t convinced that a broader recovery is going to take. As Irwin explains, it comes down largely to sluggish demand: CEOs believe “U.S. consumers are destined to disappoint for many years. As a result, they say, the economy is unlikely to see the kind of almost unbroken prosperity of the quarter-century that preceded the financial crisis.”

This, indeed, is the sort of deadlock that makes for dreadful recessions-demand stays sluggish, while gun-shy firms can’t talk themselves into the same damn-the-torpedoes boosterism that helped sustain prior booms. It’s also, not coincidentally, where the Keynesian measure of increased government spending can help lubricate demand in a chilling job market. For all the exuberant voices on the right declaring the 2009 Obama stimulus a failure, the present doldrums make a stronger case for crafting a bigger stimulus and sustaining deficits while the slump persists.

But we don’t get that sort of structural breakdown of the issue from Irwin, or indeed from most of the business press. Instead we hear a lot about apprehensive bosses, who can’t quite say what they’re apprehensive about. Yes, they believe that future sales will “come in fits and starts and their customers can’t predict what they will buy in the future.”

This means that while capital expenditures are performing briskly, rising at more than a 20 percent annual rate over the first half of 2010, bosses aren’t spending to expand capacity or add jobs, Irwin notes; instead, they’re “spending primarily to replace equipment they held on longer than usual last year to conserve cash.”

But what lies behind this skittishness? Reporting from the heartland boardrooms of Chicago, Irwin frets that the executive class is spooked by President Obama’s policy portfolio. “They criticize his willingness to let Bush-era tax cuts expire at year’s end for households that make over $250,000 and allow the capital gains tax rate to increase. They dislike aspects of his landmark health-care law, and some fear that the financial overhaul legislation enacted this summer will make it harder for them to get loans.”

These and other depredations, Irwin reports, have persuaded employers that Obama’s policies “would make the United States a less competitive place to operate in the long run.”

It’s never explained, of course, how this raging declensionism squares with the “volatile conditions” that have made it harder for bosses to commit to expanding their payrolls. If Obamanomics were so rabidly antigrowth, demand would be flat, not variable-and executives wouldn’t have new capital to expend in the first place. But this stolid schizophrenia is a common tic of today’s business writing, which holds that executives are monolithically fearless and innovative entrepreneurs until a whispered rollback of a tax cut turns them into quivering neurasthenics.

Indeed, the curious thing, as Irwin notes, is that when he pressed his CEO informants to outline the specific baleful fallout that the Obamaist commissariat has wreaked on their businesses, “they drew only vague connections.” Indeed, “none of the executives interviewed linked a specific new government initiative with a specific decision to refrain from hiring.”

And with good reason, it turns out-as an accompanying graphic shows, corporate profits have rallied handsomely of late, with the second quarter 2010 total of $1.57 trillion above pre-bust 2007 levels. In other words, all this policy doomsaying from the boardroom comes from somewhere beyond the balance sheet-it is, indeed, of a piece with the voodoonomics incantations of the post-Reagan Tea Party right. Government intervention in the economy can’t aid in job creation or stimulate demand simply because, well, it’s government intervention in the economy. When you see it coming, all you can do is hoard your capital, grab your children and run!

All one has to do to see the emptiness of this superstition is to look a bit north and east of Irwin’s anxious Chicago executive class and consider the auto industry. There, you’ll recall, we had a robust bit of Keynesian activity to keep GM and Chrysler afloat-and naturally, a wailing chorus from the supply-side faithful warning that the apocalypse was nigh. At least, you know, for bondholders.

Well, a year on, GM has reported two profits over two straight quarters, the latest showing a stout $1.3 billion off of more than $33 billion in revenues. The company is now preparing to launch an IPO-the first step to getting out of government receivership. The smaller Chrysler Corp., meanwhile, reported $183 million in operating profits in the second quarter of 2010, and is performing well ahead of its 2010 profit outlook.

And funnily enough, the leaders of the heavily unionized auto sector are managing to do what their anxious counterparts in Santelli-land still lack the stomach for: They’re adding jobs. While Michigan’s economy, which was in recession well ahead of the 2008 collapse, is still in desperate straits, the state led the United States in job growth last month, according to the most recent figures from the U.S. Department of Labor. More than 20,000 of the 27,800 new jobs in Michigan were in manufacturing, and the vast majority of those, of course, are in the auto industry.

Such suggestive, uneven regional trends in job growth and manufacturing again only strengthen the case for addressing the question of our sluggish overall recovery at a deeper structural level, beyond reporting that employers, like the rest of us, are easily spooked these days. Consider, for instance, the testimony of a recent New York Times op-ed contributor, who decried the influence of a “cadre of ideological tax-cutters,” “the vast, unproductive expansion of our financial sector,” and “the hollowing out of the larger American economy”; as we’ve “lived beyond our means for decades by borrowing heavily from abroad,” we’ve also “steadily sent jobs and production offshore.” The predictable results of all these trends, we learn, is that “we will not have a conventional recovery now, but rather a long hangover of debt liquidation and downsizing.”

That wasn’t Paul Krugman-we know that from a parting warning about “recycled Keynesianism” and a call for renewed fiscal discipline. But it was former OMB Director David Stockman. You might remember him from the Reagan Revolution.

You can help stimulate Chris Lehmann’s economy by pre-ordering Rich People Things: the book

.