Every Anus' Worst Nightmare

The folks at Next Action Media call their latest opus Man gets spare rib stuck in anus, and, quite frankly, I am unable to improve on that title either for clarity or succinctness. The subject may be a bit distasteful to some, but this really functions as a practical anatomy lesson and should not be missed by anyone who is interested in animation-based news or things getting stuck in anuses. Also, the subtitles deserve 4 stars. It’s another masterpiece.

Wincing Along With Adrian Grenier

“’What you got there, a little hobby or something?’ Jay-Z asked [Adrian] Grenier. Mr. Grenier smiled big. ‘You have a great night, man,’ the rapper added. ‘You too,’ said Mr. Grenier. ‘Good luck. I know you don’t need it. Confidence! You’ve got it.’ Jay-Z looked at him through his sunglasses. ‘I was going to say the same thing to you,’ he said. He turned away and strolled into the room with the mannequins.”

City To Ban Smoking In Tacky "Pedestrian Plazas"

“You can walk up and down Eighth Avenue, across 42nd Street, smoking to your heart’s content. But you can’t sit at one of those little tables right next to me at another little table and smoke, and therefore I have to ingest your smoke. The point of this bill isn’t ‘gotcha.’”

-Council Speaker Christine Quinn discusses Mayor Bloomberg’s new plan to ban smoking in “all 1,700 parks, 14 miles of beaches, city-owned golf courses and marinas, as well as pedestrian plazas like those in Times Square.” Which, you know what? Fine. Who wants to sit in your shitty little traffic island anyway? My lungs take enough of a hit every day already, I don’t need to make them struggle more by sitting in the middle of Herald Square and ingesting all the fumes from the automobiles going by. So long as I can still sit out on my fire escape and have a cigarette or ten, I’m okay with this. When my fire escape becomes the only place in New York where I can sit out and have a cigarette or ten (which policy analysts predict will occur by 2012) then I will have a problem.

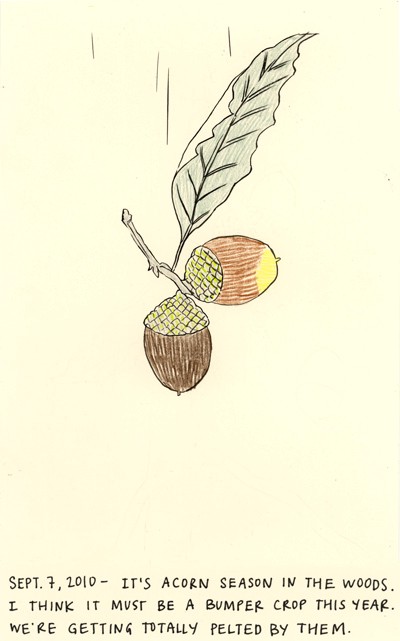

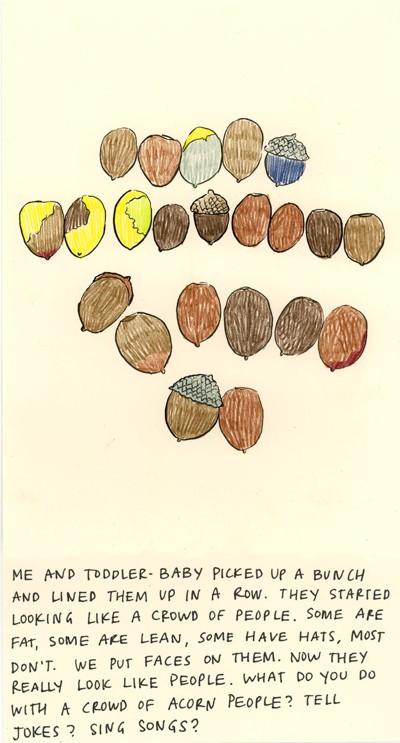

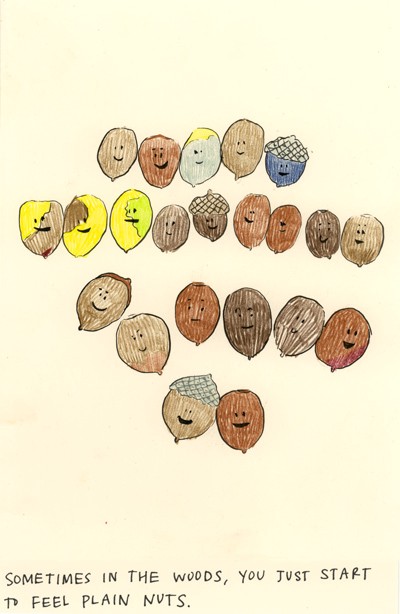

Your Nuts

Amy Jean Porter just recently finished 106 drawings for her first book, “Of Lamb,” a collaboration with poet Matthea Harvey, to be published in early 2011.

Is Your TV News Broadcast An Infomercial In Sheep's Clothing?

Los Angeles Times columnist James Rainey sheds a little bit of light on people who appear on many of this country’s local newscasts pitching toys yes, toys! is nothing sacred? and who are paid by the companies that produce the products being touted. Unfortunately, the people in the newsrooms that chase these stories don’t exactly subscribe to the old journalistic maxim of “If your source says she really really really loves a toy and mysteriously is able to travel around the country with nothing but this particular message in mind, check her income stream out”:

Werner is a lawyer who worked for a couple of toy companies before she went into the promotion business. She told me that the company that hires her to do the tours — New Jersey-based DWJ Television — scrupulously notifies TV stations that toy makers pay for the pitches. DWJ founder Dan Johnson, an ABC News veteran of decades gone by, said the same.

So I picked three stations and morning programs that Werner visited over the summer — Fox 2 in Detroit, Fox 5’s “Good Day Atlanta” and the independent KTVK’s “Good Morning Arizona” in Phoenix — to see how they plugged the Werner segments. A spokesperson for the two Fox stations and the news director at the Phoenix outlet told me they had been told absolutely nothing about Werner being paid to tout products, which ranged from a Play-Doh press to a new Toy Story video game to the Paper Jamz electronic guitar.

Assuming they really didn’t get any notice of Werner’s pay arrangement (and the Phoenix station offered one e-mail that didn’t disclose the sponsorship), that would put the stations in the clear, right?

Wrong. Anyone who has spent more than five minutes in a newsroom knows that when someone comes through the door offering their expertise, you start asking questions. With Werner, a reasonably diligent news producer, to paraphrase the FCC, would have started by demanding: So, toy gal, do you get a natural high about mechanical bugs and talking books or is someone paying you to make like Tom Hanks in “Big?”

It’s a no-brainer for TV producers to ask where experts are coming from, said DWJ’s Johnson. Believing that an expert would tour the country without pay to tout products is, he said, like believing in the tooth fairy.

Now, this “we had no idea, really” could be the stations playing really dumb denying their guilt in the hopes that Rainey wouldn’t pursue the matter further. Or it could just be that they don’t get paid enough to care about where their “experts” are coming from, and just hope that the person they have on can be coherent enough to fill those all-important minutes leading up to sports and weather. Or (perhaps most likely) the producers are more than well-acquainted with the writing on the wall pointing toward the LX.TV-ification of their chosen profession and so they’ve decided to just wave the white flag of infoadvertorial nontent early, because what does the word “news” mean at a point in time where people can just fill their heads with updates on the offscreen lives of the Teen Moms and the Kardashians anyway? God, do those producers need a drink, like, now.

(Also, the funny thing about the Big reference? The Paper Jamz guitar is actually a sort of takeoff on the big keyboard Hanks played with his feet in that movie, in that it’s super-thin:

I can see it lasting maybe, what, three or four plays before it shorts out?)

The Late Late Sloane

Set your DVRs for tomorrow’s edition of “The Late Late Show with Craig Ferguson” (check your local listings, but c’mon, it’s CBS after Letterman), which will feature an appearance by Awl pal Sloane Crosley. The other guest is William Shatner, so there’s a very good chance that Sloane’s next collection will be called I Don’t Want To Talk About Sulu.

Royce Mullins and The Case of Virtue's Burn, A Novel: Chapter Two

by Jeff Hart

Most of the clients that wandered into my office fit the bill of damaged goods and Paul Fennel was no different. He’d shown up bearing a referral from God himself, who hours earlier had saved me from mortal injury with a convenient ball of flaming garbage. While I’d fully intended to resume my carefree life as a non-believer, reserving my brush with death as a cute story for atheist cocktail parties, I could not deny the inconvenient serendipity of Paul’s sudden appearance. He was exactly how I imagined a lamb of God — thin, fidgety, too nervous to bleat. When Paul and the rest of the meek inherited the Earth, direct eye contact would be one of the first things to go.

Paul peered out the window while I cleared a stack of final notices from my guest chair. Three stories down, yellow-vested city workers armed with snow shovels pushed piles of Chinese garbage down 2nd Avenue. Mayor Kelly’s clean-up efforts were officially underway.

“Do you think we’ll declare war on China?” asked Paul.

“I hope not. I owe the Chinese my life.”

“Is that what you think?”

I looked up to find Paul staring at me. He quickly turned away, his head cocked downward like a dog waiting for the rolled up newspaper. I gestured to the open chair and he settled into it obediently. I sat opposite, on the futon, next to a pile of blankets rank with the smell of my sweat.

Used to be this office didn’t so much toe the line of midlife crisis bachelor pad, back when Claudette was around to keep things in shape. This was back when I was closer to having a home-office than an office-home. Those were halcyon days when I’d conduct my business with at least an air of legitimacy from behind a desk that I’d inherited from my grandfather, a real fine piece that I sold to a writer in exchange for two-hundred bucks and the same musty futon that brought on this digression. I loved that desk, but as tired as Claudette was of me, so was I tired of sleeping on the floor. Sacrifices had to be made.

“So, tell me what exactly God signed me up for.”

“Mr. Mullins,” began Paul, who had clearly rehearsed for our meeting, “I have recently met a woman whom I believe to be my soul mate.”

I felt like telling Paul, him the classic milquetoast that never had a bitter father figure pound the ways of the world into him, that they all start out as soul mates. Then they marry a vegan grocery magnate and move to Park Slope to start hatching out near-sighted cello prodigies. After that? Not so much. I kept quiet though, aware that an interruption might disturb Paul’s practiced rhythm.

“She is being held against her will by a man named Wayne Maker. You may have heard of him.”

“The guy from the subway ads? The open-yourself-to-goodness dude?”

“Yes, him,” stammered Paul. “He is the spiritual leader of The Unfettered Souls, a self improvement community I was, until my recent banishment, a member of.”

“Why banished?”

“For attempting to contact my beloved. She is of higher rank than I. It is strictly forbidden.”

“She have a name?”

“Yes, but I don’t know it. Our only time together was during The Joining. It takes place in silence and darkness.”

“So you’ve never seen her or spoken with her.”

“We connected in a more profound way, Mr. Mullins. The Joining is a transbody experience where a novice like myself bonds with an ascended member of the community — they are called Virtues — in order to reach a higher level of awareness.”

Hot as it was in my office, and as difficult as exposition can be for those unloading it, Paul had nonetheless begun to sweat at an inappropriate clip. It’s always been my experience that the abruptly and abnormally sweaty are prone to rash action or, at the very least, sudden heartfelt confidences that tend to make stiff-upper-lip types like myself uncomfortable. My advice then, and you can thank me when this saves you from getting strangled or otherwise marinated by the sloppy hug of an effusive acquaintance, is to keep your distance from those dripping with a danger sweat.

I stood up from the futon and crossed to the window, keeping an eye on Paul. He’d become aware of his condition, having left hand prints on his khakis that he attempted to wipe away before giving up and squishing his hands together in his lap.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “This is difficult for me. All these details are supposed to be confidential.”

“What makes you think this Virtue of yours is being held captive?”

“Maker won’t let her leave.”

“He’s got her chained to a divine radiator?”

“Metaphorically.”

“And literally?”

“She told me.”

“I thought you said there wasn’t any talking during the whachamacallit.”

Paul stared down at his hands.

“Our souls touched, Mr. Mullins. There was a moment of pure communication, where her soul screamed out at mine for freedom. I was frightened. I pulled back too soon.”

Paul yanked his shirt over his head. He was all cavernous rib cage and pale skin, except for the perfectly circular pink burn about the size of a coffee saucer seared over his heart. Â Â

“Shit,” I said. “Is that contagious?”

“This is what was left when our souls ripped apart,” said Paul, and looked up at me with a watery gaze of abject need the likes of which I’ve seen only in hungry babies. “You have to help us.”

“Alright,” I said. “Put your shirt on.”

I had Paul write down the address of Maker’s midtown Wellness Center, where enlightenment was apparently synonymous with balling a stranger in a dark room until she burns a hole in your chest. I’d had women leave their mark on me before, but never one quite like the raw spot over Paul’s heart. I won’t kid you. I was excited to meet her.

Previously: Chapter One

Jeff Hart lives in Brooklyn. His other writing can be found over at Culture Blues.

Photo by Fabio, from Flickr.

Turns Out Women Are Funny After All

Confessions of a Former Comedy Chauvinist: “For every Zach Galifianakis in my life, there’s a Maria Bamford, and for every Danny McBride there’s a Susie Essman or Kristen Schaal. The world of comedy is a much richer place now that I’ve stopped ignoring half of the population.”

Enjoy That Cheeseburger, Because It Could Be Your Last

Above, a new pro-vegetarian spot from the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine that’s making explicit the link between fast-food consumption and heart disease. Like, really explicit: The corpse at the center the ad died gettin’ his burger on, as evidenced by the Big Mac Of Death that remains in his hand while a woman weeps over his lifeless body. Leaving aside the obvious questions regarding the man’s grip on his burger-sized deathtrap and the process of rigor, one must ask: Why is it always McDonald’s that gets whacked by ads of this ilk? Surely one is more likely to keel over as the direct result of eating a Double Down, or, chowing his way through two feet of pizza. And it’s not like McDonald’s arches are the most visually appealing option for the kicker: A couple of tiny Burger King crowns would look so cute superimposed over the dead dude’s feet at the very end of this spot! You could even add the tagline “He had it his way… and then he died,” and you’d have a goldmine.

Ciudad Juarez: How We Got Here

by John Murray

As the violence in Mexico rages on, with murder totals recently surpassing 28,000 since the start of 2007, it’s easy for anyone watching or keeping up with the news to become desensitized. Daily stories of kidnappings and murder scenes, complete with photos of dismembered bodies piled in the backs of pickup trucks or lying bloody in the street, can make the whole scenario overwhelming and extremely hard to wrap your head around. Statistics, death counts, unsolved murders; all with seemingly no end, no beginning, and no point.

But occasionally an event or fact will strike that forces you to step back and consider the reality. The circus surrounding the arrest of Edgar “La Barbie” Valdez and the tale of his rise from American high school football player to ruthless cartel enforcer was one of those events. The mass murder of 72 migrants from Central America a few weeks ago was another. Kidnapped and brought to a remote ranch in Tamaulipas, they were reportedly given the choice to join the Zetas drug gang as mules and low-level soldiers or face immediate death. When they hesitated, they were unceremoniously gunned down on the spot.

These stories stand out against the endless tide of violence because, for a change, they are actually stories. Every day we hear of bodies found in mass graves. Grotesque beheadings and bodies dangled from bridges are commonplace. These go almost entirely unsolved and unexplained. And that’s part of what makes the Mexican drug war so impenetrable. But what gives one pause about the Tamaulipas mass murder and distinguishes it from the relentless tide of deaths is the fact that these victims had a distinct story, which is fairly uncommon in the reporting about Mexican drug war murders. Sketchy as it was, the idea of these people migrating from Salvador or Guatemala, over the border crossings in Chiapas and up through Veracruz, seeking less-than-minimum-wage work in the United States only to be derailed by sociopathic madmen, is much more detailed than one is used to reading. It’s their story that allows them to be humanized, a rarity in a campaign of terror that has the direct intention of dehumanizing its victims.

Who are these 28,000 dead? Where did they come from? And who are the countless others allowing the drug industry to keep existing, to flow virtually unabated, as if the war going on were not affecting it at all? These questions are taken by most press accounts, and by most reading them, to be foregone conclusions.

But there are macro trends that can illuminate why this situation might have developed as it has. We know that drug trafficking finds its roots in poverty. In Colombia, the ultimate source of cocaine is rural growers of coca who really have little to do with the actual trade itself. It’s the Colombian cartels and crime gangs who process and prepare the cocaine for shipment and international distribution. The same is true of Mexico. Farmers in rural areas have been the source of marijuana and opium derivatives that have been smuggled into the United States for the better part of a century.

It’s easy to say that poverty breeds an attraction to drug trafficking. People need money to survive, and they’ll get it any way they can. In many rural areas of Mexico, such as Sinaloa, Durango, Chihuahua, the economy and infrastructure just aren’t there to support survival by many other means.

But if the drug trade has grown and expanded to different parts of Mexico over the past few decades, so has the amount of people working in it and supporting it. And where have they come from?

The truth is that the rise of modern drug trafficking has in large part coincided with major changes in the Mexican economy that have displaced and altered the lives of many citizens. Looking at how events have unfolded, and considering widening income class disparity and slow job creation despite the promises of NAFTA, the past and future of drug trafficking in Mexico is in many ways linked directly to its economy and the ability of the government to provide social support for its citizens.

For decades prior to the 1980’s, Mexico’s economy grew under largely protectionist trade policies. While this caused Mexican companies to produce low-quality products with outdated technology at high prices, it also created millions of factory and industrial jobs and had a lot to do with Mexico’s economic growth over the middle part of the 20th century. With little to no foreign competition at the production and retail levels, nothing threatened Mexican businesses. However, the Latin American debt crisis of the 1970’s began to spur talks about moving Mexico further into the private sector and opening it up to international investment.

In 1986, the Mexican economy did just that, under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). Tariff barriers were dropped, the market was flooded not only with American goods but cheap goods from Asia that were produced for a far lower cost, and Mexican companies were ultimately unable to compete. The aim of GATT was ostensibly to lower the price of goods and bring Mexican industry up to speed with the rest of the world technologically and in terms of productivity. In many ways it was an inevitable change. But the suddenness of the decision was resounding, and the immediate cost was millions of factory jobs lost over the next few years throughout Mexico.

Around this same time, as the Caribbean and Miami became increasingly policed and harder to navigate for smugglers, the cocaine trade was shifting out of its traditional routes and into Mexico. With cocaine came cocaine profits, which were astronomically higher than the marijuana and opium profits the Mexican smugglers mainly relied on. So, at the same time that millions of jobs were lost in Mexico, a multibillion dollar industry flush with liquid cash arrived.

The presidency of Carlos Salinas in began 1988, two years after GATT. Salinas emphasized fewer government expenditures on social programs, and effectively put an end to the revolution-era agrarian land reform programs that had been limping along unsuccessfully for the previous 50 years. Salinas forwarded the initiative to change the Mexican constitution to allow the privatization of peasant agrarian lands, and they became available to large agricultural companies both national and international.

This increased a migration of rural Mexicans to cities that had already begun with the end of subsidies intended to help them maintain their plots of land. Huge slums grew bigger on the outskirts of Mexico City and other major industrial cities. In these places, poverty and hopelessness festered. It was the perfect breeding grounds for gangs and unrest. The US owned maquiladoras that sprung up in Juarez in the wake of NAFTA created another migration, as Mexicans and Central Americans flocked to the factories in search of jobs. The city’s population skyrocketed, but the low wages and high turnover didn’t provide any lasting benefit for the workers, and the city’s outskirts also became migrant slums, where to this day gangs like Barrio Aztecas and the Artistic Assassins (gangs affiliated with the Juarez and Sinaloa cartels, respectively) flourish.

Another symptom of the fallout from the loss of domestic manufacturing jobs was the rise of the informal economy. This consists of people operating outside the jurisdiction of government or business oversight; they don’t pay taxes, they don’t own stores, they don’t participate in the larger economy. This is the sort of business that people in dire straits resort to in order to survive, and Mexico’s informal economy is thriving. Of course, one sector of the informal economy is the black market for contraband, which in the case of Mexico is dominated by a huge volume of illegal drugs. Just as people resort to the tamer informal economy by selling bootleg CDs or fruit and vegetables, people certainly resort to the better-paying drug trade.

These events are not meant to be portrayed as directly causal. But they are facts. It’s significant that the timeline along which the Mexican economy underwent dramatic changes, including job loss and growing concentrations of poverty, coincided with the rise of the modern major Mexican drug smuggling operations. Fortified with cocaine profits, drug smuggling was a growth industry in Mexico throughout the 90’s, and provided the liquid cash injections that the economy needed as more money in Mexico was leeched away by foreign companies and domestic jobs disappeared. Indeed, it’s been reported that much of the corruption by the drug cartels of government officials in the Salinas administration and before came with the understanding that cartel activity would be overlooked provided they kept the money in Mexico. This was also a key part of Amado Carrillo’s pitch to be left alone in exchange for forfeiting half of his holdings to the government.

These are the background stories that help us make sense of how we got to where we are, and where some of the nameless dead in Mexico’s drug war might have come from, and for what reasons. Illegal immigration to the United States also skyrocketed in the years following the passage of NAFTA as a result of many of these same events, including the crash of the Mexican economy in 1994. Many of those dying in Juarez and other border cities probably aren’t even affiliated with cartels in their own right. They’re hired as sicarios from all over Mexico, and they kill for dollars a day. A great deal of killings are contracted down to street gangs, as are muling jobs and other low-tier responsibilities. Essentially replaceable, these people are used and disposed of. They are never afforded a real narrative. They speak only as the dead.

John Murray is a lover of obscurity. He lives and writes in Arizona.