Glenn Beck as America's Professor

by Mike Barthel

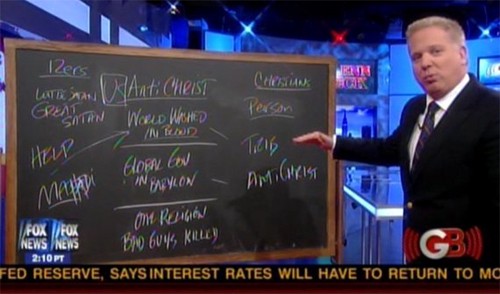

Recently I decided to check in with Glenn Beck. (I do this semi-regularly with all the various cable news talk shows out of a sense of responsibility, though I never last more than about 10 minutes at a stretch.) I was not optimistic. Based on the clips I’d been exposed to by people who don’t like Glenn Beck, I expected a mix between a revival meeting, a Klan rally, and the McCarthy hearings. Instead, I got Glenn in front of a blackboard, lecturing about…Calvin Coolidge.

I found this hilarious. In terms of presidents, it’s like giving a lecture about James Bond focused entirely on George Lazenby. Coolidge lucked into the presidency after Warren G. Harding died (Harding having made the fatal mistake of speaking at the University of Washington), and is primarily remembered for being very quiet. But Beck seemed to love the guy, which struck me as odd given that Coolidge was in office from 1923 to 1929, a period which may have seemed fun at the time but which we would regard today as somewhat misguided in terms of public policy.

A quick visit to Coolidge’s Wikipedia page, however, will tell you why Beck likes him — he’s a prototypical small-government conservative — while also suggesting that Beck’s viewers have made a few alterations to the page; for instance, Coolidge is praised for not including any members of the Klan in his government. (Wow, sure, cookies for everyone!) Nor was this episode an anomaly: Beck is now going after Woodrow Wilson, who’s at least the right target even if Beck’s going after him for the wrong reasons.

Besides the strange choice of subject matter, I was struck by the delivery: a guy who’s trying to advance a populist political agenda was performing an hour-long academic lecture. As someone who has spent his share of time in front of a classroom, it struck me as perhaps not the best way of seizing the attention of a television audience. If that’s all you’ve got, then great, but Beck is clearly adept at producing emotionally compelling arguments through theatrical gestures. What does he get out of posing as a professor?

Well, scholarship has a certain authority, and Beck would like to claim that authority. In the post-civil rights era, Beck’s familiar us-versus-them stance can’t be framed in terms of identity; most of his audience may be white and middle-class and older, but even older middle-class white people would be uncomfortable publicly making the argument that they deserve to be heard because they are older and middle-class and white. Instead, he (and many other media figures on both sides of the spectrum) utilize the stance that their audience deserves to be heard because they’re objectively correct about certain things. They simply know more than other people, the argument implicitly goes, and this knowledge only belongs to a select group. That lets you draw us-versus-them lines without coming off as a bigot. Unless you’re going to turn to mysticism, however, the only place you’re going to locate that kind of elect intellectual authority is in scholarship.

The problem for Beck and others on the right is that they also have a cultural distrust for the institutions that normally produce scholarship, which are a) liberal, b) elite, and c) collectivist. If the conservative worldview finds self-worth in rugged individualism, then the structure of the academy, in which those deemed worthy are allowed to engage in a lengthy apprenticeship to a figure of authority who’s probably an old hippie, isn’t going to work for them. Indeed, Beck’s only college experience is a single theology class at Yale in his mid-30s. Instead, his post-secondary education has come through a program of self-directed learning, pursued largely through book reading; he’s said his curriculum has included works by Alan Dershowitz, Pope John Paul II, Adolf Hitler, Billy Graham, Carl Sagan and Friedrich Nietzsche. (From which he learned, one supposes, that billions and billions of Jewish lawyers can be saved through the power of Jesus Christ, assuming they have a will to power and don’t have any abortions.)

In other words, Beck is taking advantage of the American tradition of the “self-made man.” The phrase itself originates with Frederick Douglass, who applied it both to himself and to consummate Yankee Benjamin Franklin. By framing such an identity as fundamentally American, it transfers the respect we know to give to Jefferson’s much-fetishized yeoman farmer to men of more ephemeral pursuits: teaching yourself and making your own way in the world becomes like building your own house and growing your own food, self-sufficiency as a mark of worth. Of course, both Franklin and Douglass had no option but to be self-taught, given that the public school system did not exist at the time, and Douglass, as a slave, was legally prohibited from learning to read, whereas modern Americans have access to a still pretty great public school system and the best institutions of higher learning the world has to offer. Nevertheless, the romantic image of the self-made man continues to resonate with qualities of individualism and hard work in the American imagination. That’s why the fact that certain tech-industry pioneers (and what-have-you) dropped out of or did not attend college is seen as greater evidence of their genius. This kind of authority fits particularly well with the image Beck’s trying to project: if the knowledge that makes his cause just is accessible to anyone, the movement can’t be elitist, exclusionary or based on identity. At the same time, since exceptional effort is required to acquire the knowledge, possessing it makes his audience special. Sharing this knowledge communicates the idea that those in his audience are creatures of worth. Just as the right believes that anyone can be rich if they try hard enough, so can anyone agree with Glenn Beck if they are willing to put in the work.

The problem with this sort of learning, though, is that there’s no one to tell you if you’re getting it wrong, no one to tell you about the dangers of historical analogies. And even if you do get it wrong, that opposition is easily seen as greater evidence of your own inherent rightness. You’re not misinterpreting evidence; you’re shaking up the establishment! A recent Economist article nicely summarizes the problems with Beck’s method:

If you try to teach yourself history and political science from scratch, you’re likely to draw a lot of shallow and inaccurate conclusions, particularly when you’re the sort of person who’s predisposed to seeing things in terms of white hats and black hats. One role of instructors, particularly at the college level, is to smack down the sweeping generalisations and facile analogies their students tend to make, and try to force them to adopt more rigorous and complicated approaches. But what if you’re surrounded by people who reward you handsomely for making sweeping, slanderous generalisations, both because it delivers ratings and because it’s ideologically helpful?

There’s certainly nothing wrong with not going to college or with being an amateur historian. My father has made a productive second career for himself writing in-depth histories of baseball and/or the Civil War. Doing primary-source research, or just getting out into the world and doing things that don’t require professional certification, are still excellent ways of pursuing the self-made ideal. But for any pursuit that requires an extensive knowledge of what’s come before, the Beck technique of only consulting secondary sources leaves the erstwhile scholar without the ability to critically evaluate which are right and which are wrong, or to understand arguments as elements of a widely-accepted larger narrative rather than as totalizing explanations in and of themselves. For that, the academy, as reviled as it is, is still pretty hard to beat. It’s no accident that the practice of academic work has sprung up in most major world civilizations; it’s a great way not just of producing new knowledge but of passing on existing scholarship as a kind of oral history, as institutional knowledge of what’s worked and what hasn’t. Today, you see this in general exams, a rite of passage when faculty gather to assess whether an aspiring scholar has adequately memorized the body of knowledge pertinent to their field — even though such knowledge is not exactly inaccessible in this digital era. What is being tested is not knowledge, but understanding, the ability to tell an accurate story about what we collectively know.

So some people are actually more qualified than others to have a discussion about what caused the Great Depression. But when Beck argued on-air that Hoover’s depression-causing mistake was backing away from Coolidge’s laissez-faire policies (rather than, say, not allowing the government to pursue more activist strategies), he’s doing so not on the basis of a careful assessment of the facts but because it fits in with his ideological assumptions: laissez-faire economic policies couldn’t have caused the depression, because laissez-faire policies only cause good things. This sort of reasoning is sufficient for politics, but in a more academic context it looks an awful lot like question-begging. Despite the props of learning he employs (blackboards, spectacles, pointers, Socratic dialogue), Beck’s technique brings him closer to the conspiracy theorist than to the scholar. He starts with a conclusion and accumulates a vast reservoir of facts to support that conclusion, even when the conclusion itself is invalid on its face. We all know conspiracy theorists aren’t to be trusted, of course. But by carefully hewing to the performance of the self-made scholar, Beck is able to make his audience feel like they’re learning something new, even when they’re just being told the same old thing.

The big question with Beck, as it is with a lot of figures in the latter-day conservative moment, is this: what is he? Is he evil? Ignorant? Performance art? Were I writing this for Harper’s or the Baffler or something, I would probably have to connect Beck’s dubious presidential scholarship to the right’s attack on American history, in which they’ve invented a religious basis for the nation’s founding (and a divine origin for the Constitution) and exiled morally problematic parts of our past to the cutting room floor, while simultaneously promoting capitalism as a positive historical force. But honestly, I’ve always thought that painting this as a coordinated campaign was an overly generous assessment of human beings’ ability to coordinate their activities. (Especially when those human beings are so dedicated to individualism, you know?) While I’m sure there are a few people with a big-picture view nudging things in a preferred direction, at the local level where these decisions get made, I can’t help but think it’s more due to the eternal human impulse to get everyone else’s view of the world to align with your own.

The conservative guy who comes to a school-board meeting demanding that they not teach evolution just wants everyone to agree with him. As do we all! In terms of motivation, liberals’ demands that the unpleasant parts of American history be taught in schools is no different from conservatives’ insistence that they be expunged: both want the story told as they see it so that children will grow up sympathetic to their view of the world. Of course, liberals have the advantage in this case of wanting things to be revealing, rather than concealing. But that doesn’t make our intentions any nobler, particularly.

And so this is what Beck’s doing with his academic excursions. He’s trying to accumulate enough facts so that the conservative worldview in which he believes can seem plausible once again. After all, it would take a pretty stupid conservative not to question the fundamental aspects of their political beliefs after an arch-conservative, ultra-capitalist Republican president ushered in a massive recession.

But it’s unrealistic to expect them to change their minds; after all, neither liberals nor conservatives change their political beliefs very often. Instead, we just find new ways to justify our ideology, which indicates, I suspect, that our political beliefs are more of a cultural trait than a carefully reasoned view. And that’s fine. I’d just prefer we be honest about it. If politics is something we’re not likely to be rational about, then why sully rationality by association? We can read about the past without needing it to confirm what we think about the present, and we can spin out elaborate accumulations of facts supporting a dubious conclusion without needing the conspiratorial web to be true. Glenn Beck tells a good story; Glenn Beck makes, though he doesn’t intend to, impressive art. The world would just be a better place, I tend to think, if he stuck to novels.

Mike Barthel has written about pop music for a bunch of places, mostly Idolator and Flagpole, and is currently doing so for the Portland Mercury and Color magazine. He continues to have a Tumblr and be a grad student in Seattle.

I'd Rather My Flight Crew Not Be Drinking Martinis And Taking Ecstasy, Thanks

I’m of two minds about this new Virgin Atlantic ad. On the one hand, it’s titillating and great fun to watch. (As was the ridiculous ad for Russia’s Avianova airlines.) I like the song, a heavy cover of Nina Simone’s “Feeling Good” that sounds a little like Rufus Wainwright but is apparently by the popular band, Muse, whose other song, the one about revolution or whatever that bites the melody line from Billy Idol’s “White Wedding” and gets played on the radio a lot, I don’t so much like. And in a way it’s nice to imagine naughty-girl porn-stars will serve me ice-cream that comes out of their chests and melt into milk at 30,000 feet. And yes, I would like the pilot of any airplane I’m flying in to be cool and confident. But do I really want a rakish rock star, walking down the red carpet in his his shades, zooming off into a disco-space nightclub where giant mirror-balls spin and beautiful people party in martini-glass hot-tubs? I don’t know. I think I’d prefer a nice, careful nerd like Sully. These guys come off like Liam and Noel Gallagher.

Come to God: Insane Clown Posse

Here is more on the still-shocking revelations that Insane Clown Posse is a Christian band. They sound depressed. And why not? “It’s just a terrible twist of fate for Insane Clown Posse that theirs is a form of creative expression that millions of people find ridiculous.” We wonder how our favorite Juggalette is faring.

31 Days of Horror: "Frankenhooker"

by Sean McTiernan

There’s many ways one could interpret “Frankenhooker.” It could be seen as a meditation on breaking up. A warning about the obsessiveness and nostalgia that accompany the grieving process and how trying to fill that hole with sex and drugs is dangerous and harmful to everyone. You could see it as a simple tale about what one man will go through just to be happy again. Or you could just take it as a warning not to explode a load of prostitutes, sew them together and stick your dead wife’s decapitated head on top. Whichever you decide, they’re all good lessons to learn.

Jeffrey Franken is director Frank Henenlotter’s most endearing lead character. At the start of the movie he seems shy but happy with his life working in a powerplant. He tinkers with electronics and medicine, he got kicked out of three medical schools-they “upset” him-and he and his girlfriend Elizabeth, the standard dippy, endearing and doomed Henenlotter lady, are going to be married. Things quickly go south however when Elizabeth stands in precisely the worst place one can stand when demonstrating a remote-controlled lawnmower. One shredded lady and the local news is on the scene. Not for the bizarre death so much as the fact that not all of Elizabeth was found. It quickly becomes apparent Jeffrey knows exactly where those parts ended up and they play a large part in the plan he has for the lightening storm due to hit town in a couple of days. Now all he needs are some more parts. And, as he astutely observes out loud to no one in particular, he knows one street in town that’s exactly the kind of meatmarket her needs.

Jeffrey Franken is the exact opposite of fiction’s greatest mad scientist: Jeffrey Combs’ performance as Herbert West in the flawless Re-Animator Trilogy. While Herbert West is so intense he could probably reason living people to death and re-animate corpses just by staring at them, Jeffrey approaches everything he does with a mild nature and pleasant affability. Jeffrey always seems like he’s fixing a garden shed. Even his leering over prostitutes while deciding which part of them he’d like is completely non-threatening and jovial. His remorse over what he does seems real but he doesn’t go completely to pieces about it (oh yes) and there’s always his go-getting attitude to make the best of a bad situation (semi-intentional mass homicide being a pretty bad situation).

The scene that encapsulates everything there is to love about “Frankenhooker”: The Movie and Frank Hennenlotter: The Dude happens at around the thirty-five-minute mark. Up until then the movie has been relatively tame and actually quite sad. Sure, Jeffrey eats dinner with his fiance’s severed head (complete with a winsome visual pun on not being able to hold your drink), but that’s less about grossing you out and more about showing poor Jeffrey’s struggle with acceptance. And yes, he does use trepanning but again, compared to something like the cold turkey scene in “Brain Damage,” that seems positively quaint. Even the sudden dismemberment of Jeffrey’s one and only Elizabeth Shelly (yes yes, well spotted) at the start of the movie happens off screen. So up until the thirty-five minute-mark, things have been mutedly gorey and sweetly sad.

But when Jeffrey gets into the room with the ten prostitutes though, nonchalance is not a word you would associate with this movie.

Now in the scene beforehand, we see Jeffrey engineer some supercrack that he claims will painless kill the prostitutes, thus making it easy for him to harvest the parts he needs. This is actually the only scene in the movie where Jeffery goes a little Herbert West. Few things are creepier than seeing a man deciding that making poisoned supercrack doesn’t “really” make him a murder. Especially when he follows this by testing the supercrack on an unsuspecting gerbil, while speaking to it as if it were a prostitue. Never have I been more disquieted than having to watch a man tell a gerbil to “get into the car, honey.”

But once Jeffrey gets to the scene and goes through the measurements, he gets buyer’s remorse. Announcing that “you’ve all been so nice, I can’t go through with this,” he tries to leave. But the women of the night discover his supercrack and smoke it while restraining him. After this you assume, they will meet the “painless” end Jeffrey designed for them… which makes it a pretty fucking big surprise when they explode. And not gory-splattering-horror movie explode either. These women explode into flames.

It is disgusting, hilarious, ridiculous, probably unspeakably sexist and weirdly charming all at once. And it wraps up with another trademark visual pun when Zorro (that has to be in the Movie Pimp Name Hall Of Fame, right?) gets hit with his main lady’s head.

Jeffrey, staying true to his constantly endearing (oh and woman-butchering) character, gathers up all the parts, promises to put them back together again and then makes off to stitch together a body for Elizabeth. But when he does things don’t quite go according to plan. Instead of a perfect body for his perfectly resurrected wife, Jeffrey gets knocked out by a superstrong zombie prostitute with zero in common with his wife aside from her face. Said zombie prostitute then goes on the prowl, barking the variations of the last ten sentences of the women in the room spoke before they exploded and killing men by either pushing them into traffic or having sex with them till they go on fire. Mondays, am I right?

Ex-Playboy Playmate (not sure if the “ex” should be there, maybe it’s like being the President?) Patty Mullen does a fantastic job as the titular Frankenhooker, jerkily wandering around New York’s seedy backstreets barking at people about money. And when she comes back to her old self, she’s heartbreaking (and eventually bitterly sarcastic).

Now you probably think I’ve given away all the best bits. Wrongo, friend. The last ten minutes of “Frankenhooker” are pretty peerless. That’s right, in a movie where prostitutes explode and pimps named Zorro (I mean, what a great name, can we agree on that?) take zombie prostitutes in their stride, Frankenhooker manages to pull out more stops. Take it from Bill Murray’s blurb: “If you see one movie this year, see Frankenhooker.”

Sean Mc Tiernan has a blog and a twitter. So does everyone, though. He also has a podcast on which he has a nervous breakdown once an episode, minimum. You should totally email him with your questions / insults/ offers of tax-free monetary gifts.

Carl Paladino and Militant Islam: Together in the Struggle

“Adam Lambert’s shows… are outrageous, with lewd dancing and a gay performance that includes kissing male dancers, this is not good for people in our country.” –The Pan Malaysian Islamic Party.

“I just think my children and your children would be much better off and much more successful getting married and raising a family, and I don’t want them brainwashed into thinking that homosexuality is an equally valid and successful option — it isn’t.” –New York candidate for governor Carl Paladino.

Sacred Music: Are Animals Spiritual Beings?

Chimpanzees dancing themselves into a trance state beneath a waterfall. Wolves howling at a full moon. Cats eating catnip til they’re writhing on the ground and chasing imaginary mice. Are these animals undergoing something like what humans refer to as spiritual experience?

University of Kentucky neurologist Kevin Nelson, whose book The Spiritual Doorway in the Brain will be published in January, thinks maybe so.

“Since only humans are capable of language that can communicate the richness of spiritual experience, it is unlikely we will ever know with certainty what an animal subjectively experiences,” he tells Discovery’s Jennifer Viegas. “Despite this limitation, it is still reasonable to conclude that since the most primitive areas of our brain happen to be the spiritual, then we can expect that animals are also capable of spiritual experiences.”

We won’t know for sure until one of Dr. John Cunningham Lilly’s dolphin friends opens up and translates a cetacean sermon for us (clicking in tongues?).

But Marc Bekoff, a professor emeritus of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Colorado, Boulder, agrees with Nelson’s ideas. “For now,” he says. “Let’s keep the door open to the idea that animals can be spiritual beings and let’s consider the evidence for such a claim.”

Let’s! And as anyone who likes to watch rock videos on YouTube all day knows, evidence abounds.

After Goldman Sachs, the Value of Greece, Isle by Isle

The Greek island known variously as Holy Ghost, The Island of the Father and the Son and the Holy Ghost, Holy Trinity, or just plain Trinity, owes its greatest renown, despite its lavish New Testamentish nomenclature, to the cameo role it played in the pagan classical age. This 12-acre slip of an atoll was a staging ground for the Persian armies laying siege to Thermopylae, the famed last stand of those hot, well-oiled Spartan souls hymned by our own latter-day Thucydides, Frank Miller. Now, however, Greek government officials are straining to find a way to convert Holy Ghost, and the nation’s 6000 or so other island outcroppings into liquid assets, so as to begin paying down the country’s colossal €400 billion debt flowing from the European Union’s bailout of the basket case known as the Greek economy.

But as A. Craig Copetas reports in Business Week, preparing these vast holdings for sale to foreign investors-and the buyers pretty much have to be foreign, if Greece is to get any viable capital out of the deals-is no mean feat. There is, first of all, the question of ownership; most of the properties are in private hands, and not the government’s to sell. There will be plenty of government perks, of course, via the tax revenues, tourist, levies, construction jobs that a battalion of foreign-funded resorts would likely generate-to say nothing of the untaxed stream of bribes and kickbacks that would also accrue to Greece’s legendarily corrupt and bureaucratic state.

But with conflicting ownership claims going back several centuries, if not in fact to the dawn of Western civilization, the provenance of any given land title makes for a hermeneutic nightmare even without the 2500-odd forms and official clearances that Greece requires in order to process a significant land sale to a foreign bidder. “The labyrinthine federal, state, local, military, and religious regulations, decrees, laws, proclamations, and edicts,” Copetas writes, “have made it nearly impossible for anyone to sell anything, because no one can agree on who owns what.”

Holy Ghost island, as Copetas notes, is a perfect case in point. It sits some 50 miles from Athens, via road and boat. Its outsized dalliance with history continued down into the modern age, when the Beatles sought to purchase it after spending a mod Mediterranean getaway there in the 1960s. They petitioned its then-owner, Sophocles Papanikolaou, chancellor to the Greek Royal Court, to unload, but three years of negotiation proved fruitless. (In another footnote to Holy Ghost’s protean way with renown, Papanikolaou’s cousin Georgios is the doctor who invented the pap smear.)

The Greek Orthodox Church, meanwhile, is convinced that it is the island’s true owner, and as Copetas writes, Church fathers will gladly part with the property, so long as the eager-beaver resort developer coming into it will also spring for a chapel, a baptismal font, and numerous other trappings of Orthodox piety. I suppose for the right sort of savvy island entrepreneur, this could be an opportunity all its own-the basis for a luxury getaway package combining a week of resort-and-casino debauchery with a Sunday of spa-quality repentance. Perhaps in an ecumenical nod to the Fab Four, the estate of the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi could be brought in on the act.

And for all the genuine government excess sure to attend a prospective sale, Holy Ghost would be a bargain on the tax books. While real-estate brokers value it at around €20 million, it commands a paltry €1.5 million valuation from the Greek tax office-meaning that the 9 percent sales tax would apply to the far lower sum rather than the €20 million that the seller (in this case, the Papanikolaou clan) would collect. “Cheap, yes?” a lawyer for the Papanikolaous tells Copetas after patiently laying the whole confusing scheme out.

Well, after a fashion-provided a buyer can ever emerge from the dense thicket of federal paperwork involved in any island transaction. Even though Prime Minister George Papendreou endorsed a plan to sell off prized national assets such as the islands at the World Economic Forum earlier this year, the volume of official review involved in an island sale is mind-boggling. A standard sale of such property requires eight different national ministries, from the Defense administration (since an island can’t be sold to any buyer deemed potentially complicit in plans for a future Turkish invasion) to the Culture division, an island realtor named Katerina Samaropoulou explains. Then, “once you have the eight ministries signed on, and depending on where the island is and its legal status, you go back to the Finance Ministry to see if they want to buy it at the tax-office price,” she notes-something that the Greek government would definitely be wise to do, given the lowball assessments granted to spots such as Holy Ghost.

Though on the other hand, the selfsame administrative leviathan hasn’t yet assembled a comprehensive registry of lands in its possession, with the government now contesting its potential ownership of some 675,000 acres of land now under title to individuals; the Orthodox Church is embroiled in ownership disputes over another 325,000 acres, bringing the overall total up to a cool million. At the bottom of such controversies, says former Secretary-General of the Economic Ministry Stratis Stratigis is a sad, simple truth: “Greek governments never learned how to count.”

However, before the genuine, howling irrationality involved in putting a Greek island on the global auction block provokes another neoliberal sermonette on the backward, baleful character of state economic oversight in our age, it bears recalling the unique public-private partnership that allowed the Greek debt crisis to spiral out of control in the first place.

Under the Maastricht treaty that grants economic membership to the European Union, a national economy must operate with a deficit ceiling of 3 percent of overall GDP. Since its admission to the Maastricht club, Greece has never actually hit that magic number-at times omitting to count big-ticket items like military operations and health-care debt in its makeshift deficit inventories. But the real creative accounting began when the global derivatives market-and a plucky little investment bank named Goldman Sachs-threw sultry come-hither looks at Greek financial officialdom. Via a complex battery of cross-currency trades, Goldman tethered Greece’s currency to an entirely fictional rate of exchange in order to mask its true scale of debt-and all the while, Greece just continued to run up the tab. The rigged exchange setup “enabled Greece to receive a far higher sum than the actual euro market value of 10 billion dollars or yen” involved in the Goldman deal, according to Der Speigel. “In that way, Goldman Sachs secretly arranged additional credit of up to $1 billion for the Greeks.” Since Maastricht rules don’t require disclosure of financial derivatives-and indeed, don’t even count currency trades as debt in the first place-no one was the wiser, until of course, it was far too late, and Greece, like so many chastened former Goldman clients, had to settle up its toxic accounts with government scrip, and pray that they can liquidate enough of the nation’s assets to keep up with the €4 billion monthly payments that start coming due in 2012.

The grim joke, of course, is that surrendering the government’s stake in the archipelago-hospitality complex would be a onetime firesale of real assets, palliating Greece’s short-term debtholders at the EU in exchange for a mess of pottage. (Copetas reminds readers that a similar feeding frenzy occurred in the “shock therapy” heyday of the former Soviet Union, when the Yeltsin government sold off former state-run enterprises at an estimated 10 percent of their actual market value, in a desperate bid to raise ready cash. )

There is, in a way, a neat symmetry to the arrangement: Contracting heaps of unsustainable debt conjured from a derivatives market in pretend money has left Greek policymakers desperately trying to sell off the actual material basis of their country. Those same leaders, so long obsessed with the geopolitical specter of a Turkish invasion, probably never reckoned, back when they settled on their clever Goldman-backed scheme in 2002, that national sovereignty could be just another flimsy derivative-based security. Then again, you might expect them, of all people, to recall another long-ago international hustler, named Circe, who used similar numinous concoctions to transform erstwhile or spurned partners into objects of cosmic ridicule. Oh, and her Greek island was called Aeaea. I wonder what it’ll go for now.

Chris Lehmann’s book, Rich People Things, is available now for pre-order! “Social criticism at its scorching-hot best,” says Barbara Ehrenreich!

Solomon Burke, 1940-2010

Soul music lost one of its greats yesterday when the reverend Solomon Burke died of natural causes on a flight from Los Angeles to Amsterdam, where he was scheduled to perform a sold-out show. Best known for his hits “Everybody Needs Somebody To Love” and “Cry to Me,” which he recorded for Atlantic Records in the mid-’60s, the Philadelphia-born, church-raised Burke was inducted into the Rock and Rock Hall of Fame in 2001 and won a Grammy the next year, for Best Contemporary Blues Album, for his Don’t Give Up On Me. He was a gospel preacher and a trained mortician and he had 21 children and 90 grandchildren. There he is in the video clip above, singing the Don Gibson standard, “I Can’t Stop Loving You,” in Germany in 1987.

Footnotes of Mad Men: Calling All Trumpeter Swans

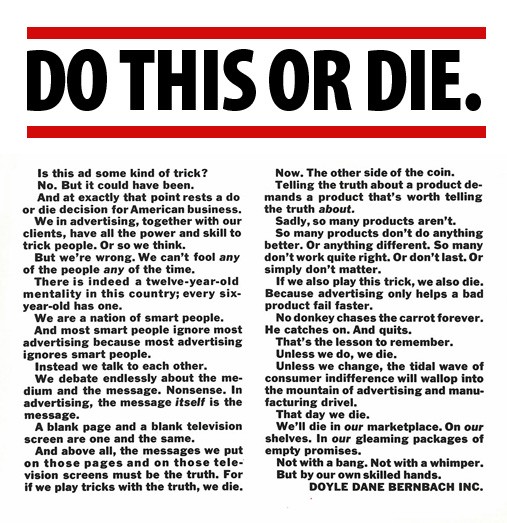

by Natasha Vargas-Cooper

Who knew that the advertising industry housed so many men of integrity? The ad above is by Bill Bernbach, a founder of Doyle Dane Bernbach and the Great Father of modern advertising. It was Bernbach who popularized the technique of counter-intuitive advertising. “Now I’m not talking about tricking people,” Bernbach said. “If you get attention by a trick, how can people like you for it? For instance, you are not right if, in your ad, you stand a man on his head just to get attention. But you are right to have him on his head to show how your product keeps things from falling out of his pockets.”

But what happens when everyone starts imitating the vanguard?

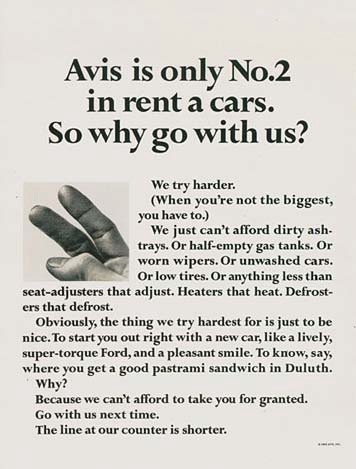

Bernbach choose to stick with the formula that set DDB out from the rest of Madison ad: use the flaws of a product to your advantage.

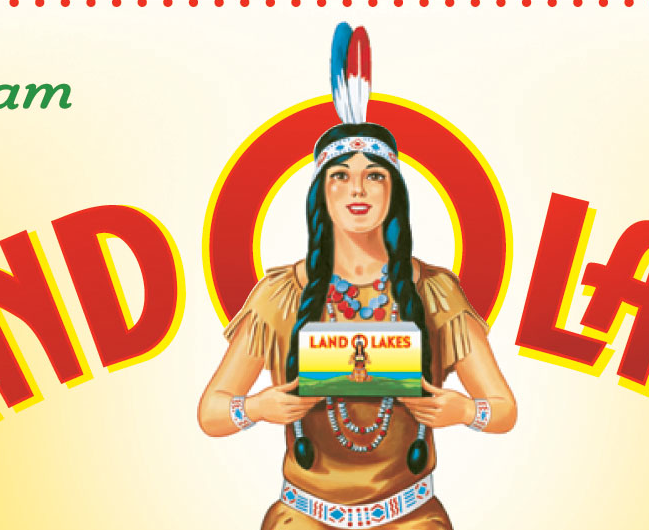

If we use Sally Draper’s Land O’Lakes example of the lovely Indian lady holding a box of butter of a lovely Indian lady holding a box of butter to infinity, in this ad, Bernbach was critiquing not just the butter but the whole box. Advertising companies did not publicly acknowledge that they were advertising companies. (As in the words of Patron Saint of Serialized Drama, Tony Soprano: “THERE IS NO MAFIA!”)

That is to say, when you admit that you are in the persuasion business, it speaks immediately to people’s fears: you are persuading them with lies. Then Bernbach pulled this stunt, breaking down the fourth wall in a mea culpa that simultaneously trashed the whole industry and valorized one of the biggest companies in the industry. Think of the Etta James song that crooned at the end of the episode, “Trust In Me”

“Trust in me in all you do

Have the faith I have in you.”

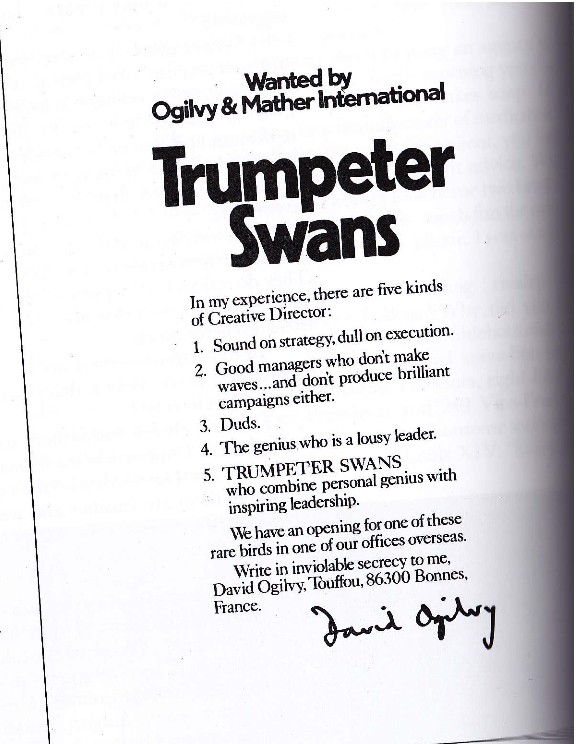

• Another master of public pith was David Ogilvy. He took the same strategy as Bernbach in calling the rest of the business a confederacy of hacks in this recruitment ad that ran in a series in several trade papers:

• “Although a crusader of the first order,” ad man Leo Burnett wrote in the pages of Reader’s Digest, “[Reader’s Digest] does not preach, but helps me reach my own conclusions.”

It was customary that the Digest would ask newsmakers to write a letter about why they read the magazine-to this day it has the highest paid circulation in print. It’s also one of the few magazines that has never run a tobacco ad. The Digest was also the first of its kind to publish findings about the link between cigarettes and lung cancer.

So Leo Burnett was an unlikely endorserment, seeing as how he was synonymous with smoking. Burnett created the most seductive cigarette icon: the Marlboro man. Nevertheless, the image of Burnett ran in the only magazine that refused to run images created by Burnett. In the ad, he praised the Digest’s decency, editorial sense and courage for taking on “knotty” or “abstruse” issues (like “some of the basic clues to the mystery of cancer”). And with a wink to his own reputation, Burnett warns the reader that the magazine “is habit forming.”

You can always find more footnotes by Natasha Vargas-Cooper right here, or, you know, you can get a whole book of ‘em.