The IRS Should Be Your Last Worry. We Can Help.

by Abe Sauer

Greetings.

I’m Patrick Cox, founder of Tax Masters. In these challenging times, there is nothing that can ruin your plans like tax uncertainty.

If you are looking at next year and concerned whether you should bother paying taxes, we can help.

Shifting magnetic poles, tectonic plate realignment, the rise of the dead, unicorns. Nothing is for certain next year… except taxes.

That is why Tax Masters is introducing its latest service, a strategic asset protection plan based on new disaster regulations passed by Congress. Our new strategic tax deferment plan for 2012 covers corporation, partnership, trust and non-profit organization taxes. Using a little known recent federal tax regulation, Tax Masters can defer all tax burdens until after 2012. If you have a tax problem, you can be sure it won’t go away on its own, even if most of the rest of the world does.

Furthermore, if the world does end, and federal services fail to function, then the government is in breach of contract and you may be entitled to full forgiveness of tax liability.

A true tax master can keep you out of a great deal of trouble with the IRS should this Mayan prophecy not come to pass. Remember, a typical tax CPA may not be the best choice as your tax representative in these times. The peace that accompanies tax resolution is within your reach today, even if tomorrow isn’t.

Abe Sauer is working on a book about North Dakota.

Massachusetts 2011: The Abstract State

by Jessanne Collins

I can’t think of a better place to spend the apocalypse than Massachusetts, where the air is tinged with woodsmoke, survivalism, and the sneaking suspicion that, whatever it is we’ve got coming, we probably deserve it. This is what I remember from last time, anyway. It was this time of year in 1999, and we were holed up in one of those punk-cum-frat houses out by the railroad tracks, stocked with bottled water, vintage Metallica bootlegs and André. On New Year’s Eve there was a bonfire. At midnight, when the lights didn’t go out, we burned broken furniture and cardboard boxes, so it would at least feel like the end was near.

Carefully considered symbolic acts like these are common in Massachusetts, which should also explain why the only pact I’ve made in my adult life was rendered there. This was a few years later, 2003 or so, a time that felt so much like the future it was hard to imagine the future. In keeping with local (read: khaki) custom, this pact erred on the side of casual. No blood was drawn. It wasn’t even a secret. In fact, in the intervening years I’ve referenced it frequently, when cocktail conversation with an acquaintance old or new revealed a kindred nostalgia. “Listen,” I’d say, with the conspiratorial tone demanded of even the least cinematic pact. “There’s this thing you might be interested in. It’s called Massachusetts 2011.”

There’s no irony or complexity to Massachusetts 2011, probably because there’s not a whole lot of irony or complexity to Massachusetts, period. It was a sort of commonly stated intention, forged individually with several disparate friends, who in turn forged a similar one with some of their own disparate friends. We all loved Massachusetts. Not enough to stay, but enough to feel homesick for it when we left. Enough to design to return to, after we had attempted New York City, dallied about the West Coast, dissertated across the Midwest. We’d give ourselves the better part of a decade to drink and date and do whatever it was one does to pass the days. And then in 2011, we’d come home and pick up where we left off.

Never mind that where we left off was a place of Budweiser and bookstore-clerking, confusion and crushing possibility, a place that would feel cartoonishly distant sooner rather than later. We didn’t know how real life, abhorring geometry, prefers the form of a textbook molecule with its awkward antennas. It seemed reasonable to surmise that by 2011, a date chosen mostly for how far off it felt (that outlandish double digit!), having outgrown our disdain for subpar public transportation and charmless bro bars, we’d be world-weary and ready to rest, like dust in a drafty triple-decker.

Upon leaving New England I learned just how New Englandy I was: kinda frosty, puritanical about painkillers. But when I started thawing out, over New York City’s proverbial overactive steam radiator, I became prone to striving and spinning and other things that used to seem indulgent and alpha and strange. So that’s where I’m at and, for the forseeable future, where I’m staying. Which is to say that — whatever else it will be — 2011 will be the year I break the only pact I’ve ever made.

It won’t matter. Everyone else, ensconced and in love everywhere else, will break it too. So, [insert German word that connotes nostalgia for something that hasn’t happened and may not ever]. There’s that. But there’s also this: my newfound devotion to the metaphysics of Massachusetts 2011. At some point, probably on a pensive drive on the Mass Pike, I figured out that my Bay State is mostly an ethos, and a glossy one at that. You may have already started to suspect as much. In my head, Massachusetts is a place of earnest industry and thoughtful gestures, like a mixtape with a liberalish government and a rustic seashore. And pond hockey!

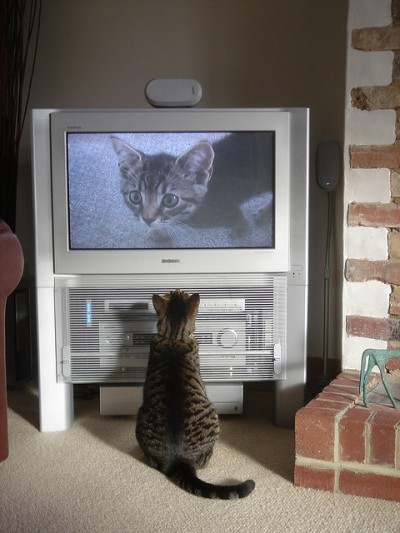

The less likely it becomes that I’ll go back in body, the more I attempt, to varying degrees of success, to live like I already have. Here is what life in “Massachusetts,” the abstract state, entails. Cooking dinner. Tending potted herbs. Reading Russian novels. Knitting wool sweaters. Making art out of last week’s magazines. Rearing rescued kittens. Conversing enthusiastically about important ideas. Weathering winter, even if it means saran-wrapping the windows. Wearing sensible shoes. Proposing a toast to the end of the world.

Jessanne Collins does in general however keep all her other agreements.

The Shake Of Things To Come

by Susie Cagle

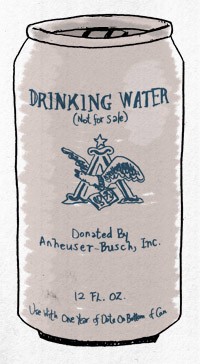

One of the things I remember most vividly about the 1994 6.7 magnitude Northridge earthquake is the Budweiser six packs of canned water they gave each of us at my elementary school a week later. I also remember waking up about thirty seconds before the quake, and sitting up in bed, and the wood shelf that fell where my head had just been. I sat on the edge of the bed and I looked out the window into the darkness and for some reason I felt like I was deep underwater as the world lurched into a kind of long, undulating wave. It lasted for 45 seconds, which of course felt like an hour. When it was over, more than 9,000 had been injured and 72 died. There was $20 billion in damage. It might’ve been worse, had it not happened at 4:31 a.m., with few cars on the road.

But still the canned water was somehow the most memorable. Anheuser Busch plants near disaster sites often divert their operations from beer to water and donate it — Louisiana and Texas were full of the stuff post-Katrina. When you see those cans of water, you know things are really bad. (Though when you see those cans of water at age ten, you also think they’re awesome, but here I digress.) And given our track record, I’m half-expecting to see those cans again in 2011, or at least some time in the next decade. After all, we’re due.

It is not a disaster coming toward us, but one that strikes under us, the earth itself erupting violently, and in this way a quake is far more insidious and terrifying than most “natural” disasters, a real-life armageddon scenario. We can predict and fight fires, floods, hurricanes and cyclones with decent accuracy — we can usually do it in time to run from them, too. But there is little one can do to hedge against earthquakes. Our most sophisticated prediction devices and dedicated seismologists are now capable of warning us of an earthquake seven minutes ahead at best. And even then, if you’re on the train, or driving across the Bay Bridge, or in a tall soft-story wood frame building with a parking garage on the bottom, you’re pretty much screwed anyway. You can’t even insure for quakes anymore, thanks to how expensive Northridge ended up being.

And so if you live in one of these quake-prone places — there are millions of us — you are staring down a little End of Days every day.

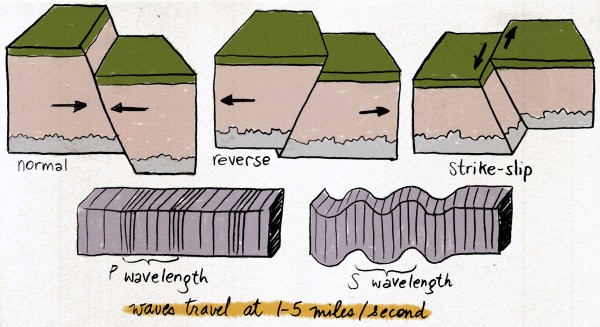

The physics of a quake vary, depending upon the nature of the plates involved and how close the waves occur to the surface of the earth, though each causes foundations to crack and highways to crumble, tsunamis and landslides, death and destruction. Each follows a basic trajectory, though. Please allow a brief science lesson: The surface plates of the earth (the lithosphere) sit on top of a lubricated layer (the athenosphere); where these plates meet, we have fault lines. The plates are constantly moving apart, which allows lava to bubble up between them, and together, building energy and causing quakes, and sometimes surface ruptures.

The nature of each earthquake is distinct depending upon the exact movements of the plates. Some push into each other horizontally, some vertically, and others move against each other in opposite directions; some have huge magnitudes, or P waves, but weaker ground accelerations, while others, like the Northridge quake, are the opposite. The stronger the ground acceleration, or S waves, the worse the damage.

About 8,000 earthquakes are recorded every day, most of them under water or in the middle of nowhere or just too small to really be felt, or cause any damage. A 7.4 like the one that hit near the Japanese islands two weeks ago, or the 7.6 in Vanuatu just on Christmas Day, if they shook under Los Angeles, would likely cause far more destruction than 1994’s $20 billion.

This year we saw some of those scenarios play out: a 7.0 in Haiti that killed 230,000 and displaced one million; an enormous 8.8 in Chile, which triggered a tsunami and killed 800; and a 7.1 in Christchurch New Zealand, which only injured two. The vast difference in resulting damage highlights the fact that we measly, delicate humans actually do have some defense against earthquakes, in designing our architecture and stocking up on canned food and bottled water. The Haiti quake was the most destructive this decade in large part due to Haiti’s fragile infrastructure rather than the strength of the quake.

Californians have seemingly unhealthy relationships with earthquakes, a kind of necessary but deep denial — we dread them and yet we half-expect them constantly, half-want to just have it happen now, get it over with. And why wouldn’t we? There is no real coming to terms with this. After all, there is a 99% chance — truly, 99% — that the state will be hit with a Haiti-level quake within the next 30 years. Broken down, that’s a 67% chance that Los Angeles will face a 6.7 or greater quake in the next 20 years, and a 63% probability for the Bay Area. That is as specific as our seismologists can get. If we’re lucky, we might find out with enough time to dig out the first aid kit or make a weepy phone call.

They’ve found that five quakes of about a 7.0 magnitude or greater have struck the East Bay’s Hayward fault between 1315 and 1868; they don’t know exactly when they hit, but that’s an average of one every 140 years. Of course, 1868 + 140 = 2008. So we are not just due, really, but overdue.

If I were feeling more abstract and maybe religious about this I might say this is a morality lesson for how we might all face down our potential (and, let’s face it, ever-closer) demise. That doesn’t seem quite fair, though. Because I’m still fucking scared. I obsessed over the East Bay shake maps before I moved into my apartment in Oakland (in a two-story wood frame structure built after new earthquake preparedness codes went into effect). I live less than two miles from the Hayward fault, but there’s no telling where an epicenter might be along that 37-mile strike-slip. Still, we’re in the “very strong” and not “violent” zone, as we’re on bedrock and not landfill. (Sorry, Alameda.)

So when people talk about our Mayan End Times come 2012, my only point of reference is 1994 and how all of the bricks from the sidewall next to our house were scattered into the street like Legos and I cut my feet on the glass in the kitchen in the dark. But this armageddon scenario is real, and for those of us in the San Francisco Bay Area, it’s coming any second now. Any… second… Now! No? Well, anyway. All things considered, our chances of survival are still pretty decent!

Susie Cagle puts her journalism degree to good use by cartooning regularly about food, politics and her old government job.

The Road To Hell Is Paved With Compostable Bags

I do not believe in things like ghosts or astrology or gods who care if you eat shellfish, so I feel unwaveringly confident in saying that the world is not going to end in 2012. If I did believe that, I think I’d whittle away the rest of my time at a months-long beach party in Thailand, physically and mentally removed from cable news caterwauling and any chance that I’d humiliate my mother in a whiskey mishap. I’d dance and probably ease my negative opinions on drum circles, and, as the sun collapsed over the horizon, I’d find someone to hold hands with and stand before the boiling ocean. I’d try to have my eyes open the instant before I became ash, and my ashes united with the ashes of everything else, flitting into the black sky and the ancient silence.

I’m not sure if that’s how the Mayans envisioned it, and I’m not a Roland Emmerich fan, but it doesn’t really matter, because, again, the world is not ending in 2012. In fact, the world is not ending for a long, long time, and for me, that’s the problem.

Most people don’t know this, but the beginning of the end of the world happened on October 5 of this year. That’s the day Frito-Lay announced it was ceasing production of most of its compostable bags due to customer noise complaints. That is, full-grown adults had whined so much about the biodegradable bags’ unusually loud crinkling that Frito-Lay caved and returned to housing its chips in standard, difficult-to-recycle mylar containers. It was one of the dumbest decisions made this year, and it went largely unnoticed for the abomination it was.

In the most famous scene from Francis Ford Coppola’s 1979 masterpiece, Apocalypse Now, Marlon Brando’s Colonel Walter Kurtz tells Martin Sheen’s Captain Benjamin Willard about a time his Special Forces unit went on a medical mission to a small Vietnamese village:

We left the camp after we had inoculated the children for polio, and this old man came running after us and he was crying. … We went back there, and they had come and hacked off every inoculated arm. There they were in a pile. A pile of little arms. And I remember, I cried, I wept like some grandmother. I wanted to tear my teeth out; I didn’t know what I wanted to do! … And then I realized, like I was shot, like I was shot with a diamond, a diamond bullet right through my forehead. And I thought, my God, the genius of that! The genius! The will to do that!

I thought of Kurtz nestled in a dank cave the day I watched Frito-Lay’s good idea fall to a handful of developmentally disabled adults bitching about noisy chip bags. Just as the colonel was simultaneously enchanted and disgusted by his enemies, I, too, couldn’t help but smile at the situation: a society amidst one of the ugliest wars in history, amidst one of the ugliest political climates in history, that bands together to protest for quieter sacks of sodium treats. The stupidity behind the drive to destroy the biodegradable Sun Chips bag was hideous, to be sure, but it was also a version of stupid so profound and pure you had to find it a little awe-inspiring before weeping with disgust.

I’m sure it sounds silly to some, but I can’t help but consider that day in October a significant landmark on the highway to our collective downfall. Staring at that heap of arms, Kurtz knew with instant clarity that his war was unwinnable. I got the same feeling looking at the Facebook group “SORRY, I CAN’T HEAR YOU OVER THIS SUN CHIPS BAG.” How do you compete with a general population whose dedication to its own comfort takes precedence above all other people and things? How do you compete with billion-dollar companies that are too craven to stick up for important innovation for fear of losing a few idiots’ dollars? Also, how do you compete with a government that allows those aforementioned corporations to buy politicians who will then lord over those aforementioned people and things?

This is what we’ve become, and the Mayans were wrong: the end of the world has nothing to do with calendar dates and solstices; the end of the world belongs to who it’s always belonged to: thoughtless jerks, jerks who live out whole lives in pursuit of little more than personal prosperity and a moat with which to keep out the realities of everyday life. Knowing this, I’ve begun to think altogether differently about things like the ice caps and the rainforest. While people like to talk often and at length about both, few if any have mentioned what I think is increasingly obvious: it’s very possible we don’t deserve the ice caps, nor the rainforest, nor any of the other miracles of life we’ve already managed to forever destroy.

In thinking about the end of the world, it’s only fair to be rigorous and think about whether it would even be a bad thing. Are we as a planet so great — with our ceaseless environmental disasters, our wars, our bigotry, our rampant and intractable inequality — that our unbiased termination would be all that disastrous or unthinkable?

Something tells me Donald Trump would hate a cosmic clean slate. Kim Kardashian, too. But what about the hundreds of thousands of child prostitutes in India? Or the countless American veterans living on the streets while Holly Madison gets paid four grand to tweet that she likes high heels? Do you think they’d have a problem with someone hitting a giant reset button? Do you think a Haitian eating mud to survive would think it entirely catastrophic to know that, in 2012, everything in the whole world would burn and be equal for the first time in his life?

I posit that we — in the broadest sense of the word — are not that precious or necessary, and that we never were. And because of this, I find it hard to fear our inevitable extinction, even if that’s only a year away. What I fear far more, and what I believe to be far more probable than some prognosticated meltdown, is a gradual, personal acquiescence to our end and its ugly harbingers. I fear waking up one day and, like David Foster Wallace or Tyler Clementi, feeling as if quitting makes more sense than trying anymore to beat back the bullshit that sometimes makes it difficult to just get out of bed in the morning.

I fear not being able to look at my nephew and tell him I believe he is headed into a good and just society. I fear losing faith in the power of one. I fear no longer being able to find glimmers of joy and hope in friends’ weddings, the birth of children, the contours of a warm body next to me in bed or a hug from my mother.

I fear a lot. And though I know the world is not going to end in 2012, I’m going to spend 2011 trying to not wish that it would.

Cord Jefferson writes for The Root, Wonkette and The American Prospect.

Going To Zero

by Kevin Depew

On July 11, 2011, I stopped paying my bills. I remember it was very hot outside and the air was still that day. I was in the office as usual sitting at my desk. Shortly after the market opened I pulled out my checkbook and a stack of bills. I made out check #1472 to “Northeast Properties, LLC” for $2,325. In the memo line I wrote, “Rent, 07/15/2011–08/14/2011.” I had just put it in an envelope and sealed it when I noticed Stuart walking toward me.

I think I said something like, “What’s up, man?”

But he walked right past me like I was a ghost. He climbed up onto the shelf just below the 10-foot window immediately to the right of my desk and reached down and opened it, knocking my phone and a couple of family photos onto the floor as he pulled the window up to its maximum open point. Hot, stagnant, July morning air made an indifferent attempt to displace air conditioned office building air before quickly falling back. Standing on the window seal, Stuart looked down at me and said, “We’re going to zero.” Then he jumped.

Below is a list of the bills I stopped paying that day:

Rent

Capital One Credit Card ending in 4773

HSBC Credit Card ending in 8137

American Express Card ending in 51113

Best Buy Credit Card ending in 1831

Barneys Credit Card

Bill Me Later account ending in 7442

Con Edison account ending in 3442

T-Mobile account ending in 4001

I also technically stopped paying my IRS direct debit for the $8,000 or so I owed in back taxes, but only because I stopped going to work the day after Stuart jumped and therefore no longer received any directly deposited paychecks so there was nothing in my bank account for the IRS to directly debit. The last time I checked my bank account it was negative $284.12. For some reason I remember my absence of money to the penny. By mid-August T-Mobile had disconnected my phone so I no longer had to deal with any collection calls.

Of course, because of 2012, the collection calls had been few and far between anyway. At first, debt collectors were overwhelmed. Then, they no longer cared. For I had not been alone in my delinquent ways. Oh no. I was actually among the tail end of the third wave of defaulters. By May it was estimated that around 100 million people formerly classified as delinquents, defaulters and deadbeats had taken up 2012 as a rationale for walking away from their debts. They called themselves The 12 Repudiators. That’s 12 as in 2012, The End of Days. After all, The 12 Repudiators sounded much better than The 12 Deadbeats.

Lawmakers initially passed what they thought might be incentives for people to avoid joining The 12 Repudiators, incentives which, after they were ignored, were revised to punishments, punishments which, after they became unenforceable, were revised to pleas, pleas which, after they were ignored, became silence.

Only the IRS bothered to call me, on August 6, one day after they attempted to debit my checking account with the negative $284.12 balance. That was my final phone conversation. Afterwards, at least for the few days or weeks or whatever it was that that my phone still worked, I stopped answering it, even calls from family and friends. Everything, the conversations, the questions, they became too much. So, instead of answering the phone, I did nothing.

Until now, doing nothing has been the extent of my preparations for 2012, The End. Until now, I would wake up each day and do absolutely nothing. I didn’t read. I didn’t get drunk. I didn’t go to the meetings where everyone prays, or the meetings where everyone fucks. I didn’t do anything. I would sometimes wander the city, but without purpose, so even that was nothing.

Sure, I would sometimes notice hunger or thirst and would spend some time trying to make them go away, but those needs occurred at such an involuntary micro-personal level that I can’t really consider satisfying them doing anything more than blinking my eyes or breathing.

Until now, I did nothing. And now this. This. This thing that you’re reading. This is the only thing I’ve done, maybe in my whole entire life. And just look at it. If there really was a god, he or she would right now strike you dead where you are sitting or standing for handling or even associating with something as pitiful as this. Until now, I did nothing. Now, I write. And it’s not enough. It’s still, properly speaking, doing nothing, and the vanity with which I hold on to every word here is so gross and pitiable that were we standing here face-to-face I couldn’t bear to look you in the eye.

*****

In the end, of course, Stuart was right. We did go to zero. I stopped paying attention to the market when I stopped going to work, but one day I overheard a couple of holdouts talking about it.

– No bid.

— What?

— Nothing. It’s over.

— Fucking idiots. What if they’re wrong?

— Doesn’t matter.

— There’s gotta be something.

— I can’t believe this is happening.

— What if they’re wrong?

— Now there is no wrong.

— What are you going to do?

— Nothing.

After that, I started writing.

Initially there was a sense of urgency to my writing, what with what everyone said was The End approaching. Perhaps you would have noted that in the first few paragraphs before I revised it out.

“Hurry,” I told myself. “The End is coming!”

But, after a period, this sense of urgency fell flat. It felt manufactured, fake.

“Urgency for what?,” I asked. “For a reader? And for the reader to then do what? To criticize? Or worse, to praise?”

“Maybe,” I later answered myself, which followed yet another revision, “the sense of urgency resides in simply finishing.”

A long pause followed. I returned to doing nothing.

“No. There is no finishing,” I told myself after a long time. “There’s only The End.”

And so what you read here, which at first, to a generous editor, may have seemed at least capable of being worked into a pacing with a sense of urgency, was revised to be flatter, more matter-of-fact, more chronicled, and then, later, revised to what you are reading now, which is none of those things.

*****

Time comes hard now. But it comes. There is no countdown clock, no final record-keeping, no balance of life accounting for The End of Days. There are no tallies and few consequences that can stand against the final one they say is coming but which nobody quite knows for sure. Every slate is simultaneously cleansed and fouled. Days slide by without being marked as such, just one period falling into the next.

Despite it all, some people persevere. With all reference points having vanished, I don’t know if they are heroes or fools, but it doesn’t matter. I see barter in Union Square. I see makeshift publishers of news and events. I see good works done for nothing.

But some people crumble. I also see bad deeds done for nothing. Literally, nothing, as no goods or property were exchanged in the violence. I see familial horrors committed in fits of pious rage and delusional anger against those whose only guilt lay in being among the last ones chosen in a random, genetic time lottery.

In the end, maybe that was why I left my own family. I couldn’t be trusted to do anything, so better to leave than to simply stay and do nothing, or worse.

It must be getting close. Everyone says they feel it. Today a mocking savagery permeates everything — it mocks us because there is no longer anything to which to affix our usual desperate illusions of permanence, and left to our own devices we’ve created a maze of unexpected atrocities interspersed with meaningless generosities that somehow, occasionally, when one least expects it, take on a vague hint of poignancy.

In other words, it’s a year like any other year.

Kevin Depew is a writer and editor living in New York City with his wife and two-year-old daughter. He is the Editor-in-Chief of Minyanville.com, a financial Web site. He is available in all the usual locations, and sometimes writes a comment here at The Awl or posts something on Tumblr under the alias Screen Name.

Photo by Jelle Vermeiren, from Flickr.

Mannahatta, Mon Amour

Before the “events” of 2011, which if you were “lucky” made your life surreal and possibly oneiric (and if you’re reading this, I’m sure you know what I mean), I had lived in a part of Manhattan (specifically: the northern or “unsettled” part) for close to two decades. Sections of this neighborhood nevertheless remained unfamiliar or “foreign” to me, although I had heard rumors about a specific “location” said to be found somewhere west of Broadway — i.e., close to the river — and most likely north of the bridge (but this fact was far from certain), a place known for its mutating and unmappable streets, represented on the internet by gray “zones” or numbered grids. I heard related stories about children and the elderly and real-estate developers leaving home and never returning; about unused subway tunnels built by prior administrations underneath the bedrock and encrusted in diamonds (now worthless); about vast swaths of virgin or “old-growth” forest stretching down to the banks of the Mauritius (as we now call it) populated by indigenous beings who predated human settlement; and finally about censored doctorate dissertations written by manic depressives who (after predicting this very future in which we now find ourselves) had without exception hurled themselves from the steel arches to their watery graves.

When I first encountered these stories or rumors or fables, it was during a period not only of youthful skepticism, but also when, owing to other “obligations” (as we used to refer to them), I had lacked the time (or really, the inclination) to look for this mysterious landscape, and so it remained undiscovered and possibly fictive, at least as far as I was concerned. In the spring of 2011, however, not long after the fighting stopped, and as soon as it was warm enough, I went outside (i.e., I left the “shelter”) with a plan to be more systematic. I wasn’t sure why I wanted to find this place, or what exactly I intended to find there, but even the possibility of its existence seemed to offer a kind of relief or possibly condolence during what we all understand were difficult conditions, to say the least.

I began at what remained of 155th Street and each day walked from one side of the island to the other. (It’s not as far as you might think.) I went back and forth, observing what remained of the city, most of which was deserted except for the stone towers and the corpses, which like those littering the mountains of Tibet were (owing to the “methods utilized”) “frozen” or paralyzed in a posture of death or “departure.” I was not deterred; by now we’ve all seen enough of these soulless bodies to be largely impervious to the instinctive terror such sights presumably would have provoked in all but the most callous of us a few years ago; then, too, the facial expressions of these victims or “casualties” (to use the official terminology) were uniformly serene, which I understand is cold comfort, but like most during this “emergency phase” I took what solace I could find.

Already the vines were beginning to stretch down from what I presumed to be the long-uninhabited regions to the north, wrapping their tendrils around the carcasses of rusting vehicles and the frames of broken doorways and widows. Soon, I thought, these streets will resemble those of Coba. Although I sometimes heard (or possibly imagined) the rustling of leaves and the crack of branches (noises quickly supplanted, at least in my ears, by the pounding of my heart) I saw no sign of animal life.

I continued to work my way north, deeper into the woods, where I passed a large house filled with broken glass and unlit rooms. I remembered hearing it described (in whispers) by two men I had observed years earlier while feigning sleep on the A-train. Fear hovered over this structure like a miasma, and as I edged past, I peered in to the rooms and observed the vaguely horrifying and decaying detritus of lives abandoned in a second and forgotten for an eternity.

The air became heavy and wet; it wasn’t so much stagnant as undisturbed. I had never felt more alone but was no longer afraid, and perhaps even transfixed by the dazzling effect of the coruscating light filtering through the canopy. The path narrowed and led me through an arch; here I detected (or imagined) a susurrus wave of disembodied voices, speaking in a language I couldn’t begin to understand. To them, I suspected, our lost cities were nothing more than anthills.

A stone lion greeted me with blinded, doleful eyes.

His twin brother had been decapitated.

I carefully walked up the steps, which were buried in leaves.

I arrived at the ruins of what appeared to be a small mansion or perhaps a guardhouse that had apparently been inhabited by the “Karma Police.” (I suppressed a shudder.)

There was no roof but the foundation seemed solid. I entered and stood in the middle of the room. I resisted the temptation to remember anything from my past, knowing that here, for once, it was irrelevant.

The sempiternal buzz of the eldritch voices reached a fever pitch. I looked out the window into a clearing, where I had had a foreboding sense of being judged. I was both a spectator and a participant in the assembling tribunal; civilization had vanished, and only the pillars remained.

Matthew Gallaway lives in Washington Heights and is the author of The Metropolis Case — which is available now! Perhaps you read its glowing, stunning review in the Times this week?

The Tumblr at the End of the World

by Sady Doyle

The planet Earth, source-point of the human race, ended in fire and flood and catastrophic nuclear-weapons automation mishap in 2012. Strangely, the entire human race appears to have been aware of the impending nuclear-weapons malfunction some eleven months in advance, but no means of preventing it were discovered. Nevertheless, approximately one hundred people survived, traveling to Mars in terraforming vehicles containing supplies and selected genetic samples. There, they began the colonies which would become the basis of our Empire. But only those deemed most crucial to the survival of the human race, by dint of talent, accomplishment, authority, or adorability, were chosen.

Some activists chose to protest what they saw as an unfair selection method and strategy, using what was then being touted as the best possible tool for social justice activism, a primitive entertainment network known as the “Internet.” And now, thanks to exploration and recovery missions, we have records of their struggle. They are elliptical, and still incomplete; the reader may wonder at their omissions. How, for example, can the activist quoted here have failed to mention the apocalypse’s chief author, Evil Count von Kanye West? (Indeed, almost none of the historical records cleared by the Central Council contain reference to the dread von Kanye. And yet, we know for fact that he almost single-handedly destroyed a planet, using what were apparently high-access security codes. How was he able to operate in secret for so long, considering his royal status, which was, explicitly, “Evil Count?”) And yet, these words — in this case, the words of one woman, a marginal yet prolific figure of whom contemporaries were often heard to remark, “you mean her? The one who puked? Yeah” — shed much light on the day-to-day activities of the dissident typing movement. This is the story of those left behind.

— R. MARK FLEBELSON, Taylor Swift Institute of Higher Learning, Women’s Studies Department, 10/4/2314

2/23/2011, E-mail, sender: Sady Doyle, subject line: “WTF????”

I can’t fucking BELIEVE this shit. The world is ENDING and Beth STILL made me want to shoot myself with that fucking post. “Staying vegan is still important??” REALLY????? Well then I guess I’ll just carve myself a ship out of a giant block of tofu, get in it, and SAIL AWAY. Did the world really have to stay around for long enough that she could write this??? DID IT????? DID IT WHYYY.

3/17/2011, E-mail, sender: Sady Doyle, subject line: “Oh, my God, I am so sorry.”

I totally didn’t realize you were copied on that e-mail, Beth. I mean, I guess you know that. But… let me know if there’s anything I can do to help. I thought your point about available food supply diminishing and meat running out was really good.

4/1/2011, Google searches: Apology, how to apologize, networking, spaceships, spaceship pilot, Community pilot, Community space episode screen caps, Community screen caps, Donald Glover, Donald Glover no shirt

5/26/2011, Tumblr, byline: Sadypocalypto, headline: “Welcome to my Apocalypse Blog! I Guess!”

So, like, with six months left to avert this nuclear weapon thing, they’re still building spaceships. SPACESHIPS! Guess who doesn’t get a spaceship? Well, you. But also, according to the overwhelmingly white, all-male panel running this thing for whatever reason even though we didn’t have an election for them, people who have “demonstrated skills at maintaining social cohesion and significant value to society as a whole.” I don’t know what that means, but I think it means you only get out if they like you.

The shock is so great that the fact we can APPARENTLY BUILD STARLINERS NOW falls right by the wayside.

Anyway, my guess? We’re not getting out. Feminists, activists, queer folks, trans folks, poor folks: None of us are going to be deemed worth saving. My guess is, they’re probably only putting one woman on those spaceships. And, given how nice and popular and sweet and universally beloved that one woman will have to be, it’s going to be Taylor freaking Swift.

7/24/2011, Tumblr, byline: Sadypocalypto, headline: “TAYLOR SWIFT?????????”

OH MY GOD I WAS KIDDING WHAT THE FUCK HOW DID NONE OF THE OBAMAS GET ON.

9/15/2011, Twitter: @Beth2012 I started Sadypocalypto “to get a book deal??!?”

9/15/2011, Twitter: @Beth2012 How the fuck am I “selling out the movement??”

9/15/2011, Twitter: @Beth2012 There’ll be NO BOOKS 4 months from now!

9/16/2011, Twitter: @Beth2012 Eat your calm-down tofu

10/1/2011, Twitter: @Beth2012 Congrats on yr book deal! Drinks soon?

11/11/11, Google searches: Tofu, cook tofu so not squishy, cook tofu so not gross, miso soup recipe, lentil soup recipe, The Soup clips, Joel McHale no shirt

12/5/2011, Tumblr, byline: Sadypocalypto, headline: “The colonists leave today. And the thing is:”

They’re saying that every colonist — every survivor, every human, in whatever future we manage to have — has to have “demonstrated skill at maintaining social cohesion.” Basically, they have to be nice. They have to be polite. They have to be bland, inoffensive, okay by everyone: Taylor Swift isn’t the only woman they’re sending. That would be ridiculous. They had to make room for Oprah, after all (although even she couldn’t get the Obamas on board). But Taylor Swift is the only musician.

And, you know? Maybe they have their reasons. Spaceships are tiny. Space is tough. Colonies are hard to start: It would be easier, no doubt, if everyone got along.

But what if I don’t want to maintain social cohesion? What if that’s not a good idea? What if every major advance, in the history of humanity, has come about as the result of someone, somewhere, doing something that caused society to just plain uncohere — to lose part of its form, and create a gooey mess, a tear in the world, a gap for something new and necessary to exist? Society coheres around the new thing (democracy, heliocentrism, the printing press, the First Amendment, women’s suffrage, civil rights, married gays in the milit… OH WAIT) eventually. It always does. Society is very good at re-cohering. But sooner or later, things are going to become unsatisfactory, and someone — some descendant of the monkeys who stood up too straight, and spent too much time on the ground rather than in the trees, and were like, “you know what we’re fond of using? Tools,” the monkeys who started to do weird, unmonkeylike, un-monkey-coherent shit and made us human — I mean to say, some member of this disruptive, unusual, massively unlikely species is going to have to stand up and go, “you know what? This shit isn’t working.” And they’re going to have to stop caring whether that starts a fight. They’re going to have to value people more than “social cohesion.”

What happens when those people aren’t around any more? Because we’re not going to be. In a few days, I’ll be gone. And so will you, most likely. All of us disruptive types, us kickers and screamers and protesters and shit-stirrers: We’re dying.

I hope you miss us. And I hope you’re more like us than you think. Because you need us out there, whether you know it or not.

12/31/2011, Tumblr, byline: Sadypocalypto, post title: “Fuck It.”

At least I’m taking you all down with me.

1/1/2012, Twitter: Wait. Is everyone else still alive this morning? Or is it just me?

1/1/2012, Twitter: HOLY SHIT WE MADE IT. HOLY SHIT OH MY GOD.

1/1/2012, Twitter: YES YES YES YES YES.

1/3/2012, e-mail, sender: Sady Doyle, subject line: “Hi, Mom”

Sorry I’m so late in responding to your e-ma

[LAST KNOWN TRANSMISSION.]

At the End of the World with Gauntlet Hair

by Matthew Perpetua

Even though we know that humanity is doomed, we haven’t stopped making or listening to music. Unsurprisingly, most people have opted to listen to old favorites, looking for comfort and nostalgia in a time of great uncertainty. Those of us who have kept focused on the present have been inundated with a seemingly endless stream of new music, much of it made just for this one moment of time by artists who have resigned themselves to no hope of legacy or lasting success.

A lot of the music is about the end. There are songs about fearing death, songs about embracing death. You hear songs about having faith that the apocalypse will not come, and others that cynically doubt that we’re actually in the end times. Some songwriters try to be rational or humorous about it all, while a lot of it is just nonsensical ramblings of undiluted panic and rage. Weirdos sing about their crackpot conspiracy theories. They point fingers, they blame themselves. They sing about how they think it will end, and how they want it to happen. People romanticize being part of the final generation of humanity, and revel in nihilism and hedonism. Everyone keeps covering and remixing and quoting “It’s the End of the World As We Know It (and I Feel Fine),” and it always sounds stupid. Aside from all that, a lot of the music is the same as it ever was — you know, songs about love and sex and pain and ego.

We pay particular attention to the famous musicians. We hear the stuff they had in the works before the bad news came, but the songs written after all that resonate more. Kanye’s real-time nervous breakdown mirrors our collective self-involved insanity, and it starts to seem like Lady Gaga was always meant to be the diva of the apocalypse. Random bands pop up out of nowhere and nail one specific fleeting feeling, and then someone else comes along and perfectly expresses the next sudden mood swing. With so many people doing so many things so quickly, there has been a rapid turnover in movements, revivals, and sub-genres. There was a month where everything seemed to have brass instruments going through extreme auto-tune effects, and the brief explosion of schizocore, this thing where kids had beats drastically accelerating and decelerating at seemingly random intervals. The memes spread, splinter off, die out, and the next thing comes along. Even with all of this delightful novelty, people complain about fads and pretend to be above it all while clinging to some notion of timelessness even as we keep running out of time.

Even though we’re all listening to different things, suddenly all this music seems important again, like it expresses something crucial about how we relate to one another. The production of everything else — books, movies, scripted television, comic books, video games — ground to a halt, but the music kept coming, flowing from hard drives to speakers around the world. Ironic, really — the technology that killed the record industry kept music alive and vital when other forms of art became a hassle.

Maybe we’ve become shortsighted. The music of the past only matters when it comforts us, or offers a new perspective on the moment. The future is impossible, so people are emboldened to take creative risks (who knew that Grizzly Bear had it in them to get so heavy, or that Zola Jesus would end up making a goth Meatloaf album?), reunite after long absences (FUGAZI! FUGAZI! FUGAZI!) or forge unexpected, wonderful alliances, like that amazing LCD Soundsystem EP with Beyonce and Big Boi. It all keeps coming faster and faster. Music from three months ago seems incredibly old. The Gauntlet Hair album may as well be Nirvana; Lil’ Wayne’s Tha Carter IV feels about as old as Public Enemy or Frank Sinatra. Every new now is both fascinating and boring, but totally amazing because it’s here and we’re alive and there’s still something left to say, to feel, to discover.

Matthew Perpetua is the proprietor of Fluxblog.

You Won't Be the Same Person When You Wake Up Next Year

by Sunny Biswas

I had this little kid fear well past being a little kid that I’d wake up a different person then the one I went to sleep as. As in, the thoughts I was having before going to bed would be forgotten by morning and the impostor waking up would have ones that were subtly, unmistakeably different in content and tone. What’s he going to be like, I’d wonder. Will he be smarter? Happier? Is he going to like turkey sandwiches better? Is he going to miss me?

That kid wasn’t 100% wrong, kind of. At around the same time he was learning that you don’t grow new brain cells when you grow up so don’t huff paint/ride rollercoasters/bang your head on the wall, neurobiologists were finding out that the opposite was true. It turns out that in a couple of parts of the brain, neural stem cells are constantly giving birth to new neurons that travel around and plug into already existing networks. Sometimes they’re replacing dying neurons and sometimes they’re just helping a part of the brain grow. (A lot of neurons don’t get replaced at all, though, so we’re about half a ship of Theseus). There’s a body of recent literature that suggests that this is how adults form new memories. Some of it also says that depressed people are worse at doing this — important chunks of our brains stay locked into these self-destructive patterns, while healthy people have brains that are malleable enough to change.

I should say here that I realize that the literature is inconclusive, that adult neurogenesis is still a controversial topic, and that as someone who does research on the topic I know enough to be very, very cautious in how I describe the connection between small amounts of experimental data and chin-stroking thoughts about how, um, thoughts work. It’s one of the strange things about studying neurobiology that you learn a lot about the brain and end up being more careful than before in tying that into how exactly you think.

But what the hell, right? I read about neural stem cells and think about how different I am from even a few years ago, and I get the weird feeling that I was right when I was little, that I’m the most recent in a long line of not very good impersonators of myself. Science (science!) confirms that parts of me are here now that weren’t there even a little while ago (and that parts of me that were there before are gone forever). In other words: one night someone else went to sleep and woke up as me. I do a lot of the same things as him but I know that I’m not the one who came up with them. I like a lot of the same things as him but I know I didn’t discover them. Otherwise I act in ways that he wouldn’t have thought of and found new stuff to like that he wouldn’t have recognized. I’ve taken that poor bastard’s place and he barely even realized it was happening. It’s awesome.

Because I’m finally starting to be okay with getting replaced. If every impostor has to keep pieces of me (a bunch of what neural stem cells do is supply neurons to already existing networks, remember), it’s more a collaboration between me and the next guy than a theft. That makes it a little less strange and even kind of cool seeing what each one has come up with on his own. Which one of us started drinking coffee? Who finally decided to buy clothes that actually fit? I wish I could thank the guy who decided to hang out with the people I ended up spending most of my time with. And I wish I knew what the next guy is going to have to keep around and what amazing thing he’s going to be original about. None of this is true for just me, of course, because it’s the same way for everyone: part of us gets old and part of us is new all the time, and the trick is integrating both.

So when the trees or robots or lizard people from under the earth start taking over in Y2K12, I’ll miss a lot of things, not the least of which is that we never figured out how we even work. But what I’ll really miss is finding out how we’re all going to be different and how we’re going to be the same. Who’s still talking and who’s going to be that guy you haven’t thought of in forever? Who do we not know yet who’s going to be part of our group? Are Andy and April on “Parks and Recreation” going to end up together or what? Will Kanye start dressing like late period Michael Jackson? And seeing how this is the internet, let’s be really self-absorbed for a bit and think: what parts of us are going to stick around and what’s waiting to be born?

It’s too bad, really, that it’s happening so soon. That’s the shame of living this close to the end — we’ll be too much like ourselves right now by the time we’re all gone. So let me just say that I hope the me who’s going to be around for the end of the world is a better, cooler person who can relax and enjoy the spectacle. And maybe also one that can hold his liquor better.

Sunny is working in a lab in Austin that studies memory formation in adult mice. Oddly enough, this involves lots of pipetting. He’ll probably end up going to med school like every other Indian person you know. He writes stuff here.

Where To Watch TV (And Where Not To)

by Adam Frucci

These days, you can watch TV pretty much anywhere. Be it on your actual TV, on your laptop, on your phone or on a tablet, they’ve made it pretty easy to entertain yourself wherever you are. But with all that freedom comes responsibility: responsibility to watch TV only when and where is appropriate. Let me help.

Your Living Room

Obviously, this is fine. This is where you have always watched TV, and it is where you should continue to watch TV. I mean, come on. You don’t need my permission to watch TV in your living room.

Your Office

You are probably not supposed to be watching TV in your office. You’re supposed to be working! But really, if you’re able to sneak in 15 minutes of streaming TV here and there, I say go for it. Nobody works for 8 hours straight; you’ve gotta have your little breaks to keep your brain from melting. So this is as an appropriate setting for TV watching as you’re able to make it.

The Bedroom

People like having TVs in the bedroom. Lying in bed and watching TV is nice! But I’m going say you really shouldn’t be watching TV in bed on a regular basis. The bedroom should be for bedroom things, like sleeping and having sex and making forts out of your sheets. Falling asleep to the TV every night is lousy for both your sleeping habits and your lovemaking habits, if you’re sharing a bed with a significant other. Maybe it’s fine to watch something on your laptop or on a tablet in bed every once in a while, but having a TV at the end of your bed that’s used daily is bad news.

The Bathroom

Yes, yes, a million times yes. I think that smartphones, and the ability to watch TV on said smartphones, has been the biggest improvement to bathroom habits since indoor plumbing. What better way to pass the time than with an “SNL” sketch or an act of “30 Rock”? The only real question is whether you’re going to watch TV or play Angry Birds when you spend time on the commode.

The Gym

This is another one of those perfect places to watch TV, a place that feels completely different now that watching TV is even an option. I mean, what did we do before we could watch TV while on the elliptical? Read magazines? Think about things that happened to us earlier that day? Ugh.

The Car

If you’re a passenger in a car, being able to watch TV while stuck in traffic is a godsend, particularly if you’re under the age of 12. I am pretty bitter that I missed the era of back seat entertainment systems when I was a kid; instead I was stuck with guessing games and conversation with my family, which, gross. Of course, if you’re driving, if you watch TV you’re a pretty serious asshole. Yet somehow, people still do this! Come on, people: dying in a car accident because you were distracted by “Top Chef” makes for a pretty embarrassing obit.

A Party

Unless you’re at a party based around watching a TV show, like a “Mad Men” party or something, don’t be that guy watching a show on his phone while at a party. That’s only slightly better than watching TV while driving, and watching TV while driving has a good chance of killing you.

Church

This one really all depends on why you’re at church. If you’re there because you really want to be there, watching TV on your phone is probably not crossing your mind. But if you’ve been dragged there against your will, I don’t see anything wrong with entertaining yourself with headphones in Homer Simpson style. If you don’t believe in god, the only judgement you’ll have to worry about are the people in the pews around you.

This post brought to you by Xfinity from Comcast. The views expressed here are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Comcast or its partners.

Adam Frucci is the editor of Splitsider, where he watches TV all day long.

Photo by Cloudzilla from Flickr.