Ten Songs For Young, Active Cats To Force Their Extroverted Woman Owners To Sing For Them (On A...

Ten Songs For Young, Active Cats To Force Their Extroverted Woman Owners To Sing For Them (On A Rainy Stay-At-Home Friday)

“The researchers determined that cats and their owners strongly influenced each other, such that they were each often controlling the other’s behaviors. Extroverted women with young, active cats enjoyed the greatest synchronicity, with cats in these relationships only having to use subtle cues, such as a single upright tail move, to signal desire for friendly contact.”

In Defense of the .50 Caliber Round

by Matt Ufford

Following the dramatic political upheaval in neighboring Tunisia and Egypt, Libya has been this week’s hot-button North African country to rise up against an oppressive regime — in this case, Muammar Gaddafi, the eccentric dictator whose 42-year reign is the longest in the region.

Gaddafi’s done a lot of crappy things: he pissed off Ronald Reagan enough to warrant a large-scale bombing in 1986, and in this most recent round of unrest he’s banished journalists from Libya and ordered his military to open fire on his own citizens. And according to some reports, the Libyan military — or mercenaries — have fired .50 caliber rounds against protesters.

And that’s where the Internet stepped in and took things out of context.

The picture here was featured on a Tumblr post that gave a plaintive admonishment.

You see that bullet?

It belongs to a .50 caliber.

You know how many inches it is?

About 5.

You know who’s taking the hits?

Libyans.

Do you know how much of an impact this is on a person’s body?

It tears them apart.

Gaddafi you are a terrible, terrible man. Subhan’Allah. Words cannot express how I and many others feel about you right now.

It’s not wise to give too much credence to any single post on Tumblr (particularly one with such casual disregard for paragraph structure), but this post is different: it has accumulated over 27,800 notes — most of them “likes” and approving reblogs — and the photo even sparked a discussion on Reddit. The alarmist, reactionary responses to the alleged use of .50 cal against people spread like wildfire:

I am going to reblog every single image of this ammunition because it should never, ever, ever be used on a human being. PERIOD. [source]

And also:

I had a discussion with my brother, who’s currently training in the police academy, about weapons that law enforcement/the military uses. Do you want to know what police departments who even have these bullets use them for? Immobilizing vehicles and shooting through walls… These bullets are designed to shred things much tougher than the human body.

Unbelievable. [source]

So: a number of tech-savvy and intelligent people are horrified by a weapon that was developed during World War I. With all due respect to the secondhand expertise of police academy recruits, the .50 caliber Browning Machine Gun (BMG) has been used by the United States military continuously since the early 1920s, and today you can find it on American tanks, Humvees, armored personnel carriers, helicopters and more. The .50 BMG cartridge is also used by most long-range snipers employed by Western militaries because the larger, heavier round is less affected by crosswinds. Expressing shock and outrage that this round is used against humans is like running outside and screaming cancer statistics at smokers.

I am, admittedly, biased for the fifty. As an officer in the Marine Corps, I had .50 BMG attached to the cupola of my M1A1 Abrams tank, and it was by far and away my favorite weapon to fire during my four-year active duty career. On a battlefield filled with distinctive sounds — the concussive WHUMP of artillery, the crack of rifles — nothing made quite an impression like the fifty, slower and lower than the staccato chatter of 7.62mm and 5.56mm machine guns. Anyone who’s ever fired a .50 caliber machine gun can instantly recognize its immutable THUB-THUB-THUB. While it may be the bass beat of death, I happen to find it soothing.

During the invasion of Iraq in 2003, I used my .50 cal to destroy artillery pieces and trucks that belonged to the Iraqi army. I never fired it at a person, but that’s largely because the M1A1 Abrams has a 7.62mm coaxial machine gun that’s better suited for that. Our rules of engagement — detailed instructions that took into account the Geneva Convention, the law of war and deference to religious and cultural practices — actually didn’t forbid us from using .50 cal against human targets. How could it? The .50 cal is used most efficiently against thin-skinned vehicles like trucks and personnel carriers, and, from a soldier’s perspective, it generally makes sense to fire at those vehicles when enemies are inside them.

None of this excuses the practice of firing at unarmed protesters in Libya. But why take issue with the ordnance? Inherent in the argument against firing .50 caliber rounds at protesters is an admission that smaller caliber rounds are permissible. I’ve seen firsthand what happens to a human body when struck with the sniper’s accuracy of the Abrams tank’s coaxial machine gun, and I assure you that 7.62mm rounds shred human flesh and end life just as terribly and permanently as .50 caliber. The cold reality is that .50 caliber is just as appropriate to fire at people as a 9mm pistol or a Tomahawk missile or a claymore or a 120mm canister shell filled with 1100 tungsten balls.

Which is to say: absolutely not very appropriate in the vast majority of circumstances.

War is cruel, and I suspect revolutions may be crueler. As communication and technology play key roles in the search for freedom across the Middle East, perhaps, in the safety of this lawful Western bubble, we can lesser the suffering in Libya by sharing information on the Internet. But in order to do so, that information must be correct, and our voices must be fueled not merely with passion, but careful reason as well.

Matt Ufford writes jokes about television at Warming Glow. You can find more of his writing about war here.

How To Break Up With A Gay

A local gay writes to say: “I need to read a blog post that teaches one how to break up with someone.” Ask and you shall receive. On Fridays, at least.

The majority of gay-on-gay breakups are done through either sudden shunning or slow fade. Gays are equally good at both. That is the Level Three breakup, and it’s really common, and I mean that in both senses. It’s easy, frequent and kind of terrible! Everyone hates to get faded on but everyone loves to always be fading.

The Level Two breakup is a sort of horrible, confusing, awkward conversation (often over phone or IM!) about how “things in your life are happening and you need to focus on them.” It’s half-assed, even when it’s true.

But Level One breakups are where it’s at.

Level One breakups are when you’ve “gone clear” on relationships (just kidding, I’m not a Scientologist, swear) and you know how to conduct yourself authoritatively and adultly. These are breakups where the relationship just isn’t right for you. (You ask yourself: “Am I enjoying this? Is this what I want?” If the answer is no, then you break up. Simple.) This isn’t for breakups where the other person is an asshole or a drug addict. (Those are easy: “Your drug use/assholism/whatever makes me unwilling to date you.”)

It’s a skill that comes and goes too! Sometimes you can sack up and perform a good breakup. Sometimes you can’t.

Basically, you can cheat on any one of these things but not more than one of these things:

A Level One breakup is:

• A serious conversation…

• …in person…

• …that includes the phrase “I don’t want to date you any more” or “I don’t want to have a relationship with you any more.” That’s a complete sentence. It may be surrounded by waffling, baffling or self-undermining sentences, but it must stand on its own and in the end it…

• … leaves the dumped gay feeling like he has been treated with respect.

To be fair, I have committed exactly one Level One breakup in my life (mmm, maybe two of them) and I have had more than my share of breakups. It’s not easy, and it’s really easy to just shine people on. And also? Just because you’ve committed a Level One breakup doesn’t mean that everyone’s going to feel good, even in years to come! But at least you’ll sleep better at night.

A Call To Arms For Awl Supporters

After what seems like an eternity of brutal suppression at the hands of an authoritarian oligarchy which shows no concern for the wishes of the people, the vast majority is rising up to say, in one clear and resounding voice, that the denial of their dreams will be tolerated no more. If you too tire of being beaten down and subjected to the scorn of those who would dismiss your desires, join the very important movement demanding that this website feature a picture of an actual awl on it. If we all stick together there is no way they can continue to keep us under their harsh boot. (Or, in this case, stylish sneaker.) Go and let your voice be heard. Let it reverberate so loudly that even the most unwilling ear will have no choice but to bend. Let the world know that no longer will you come to a homepage that lacks a visual representation of its titular tool. Shout it out from every corner of the Internet: LET THERE BE AWL.

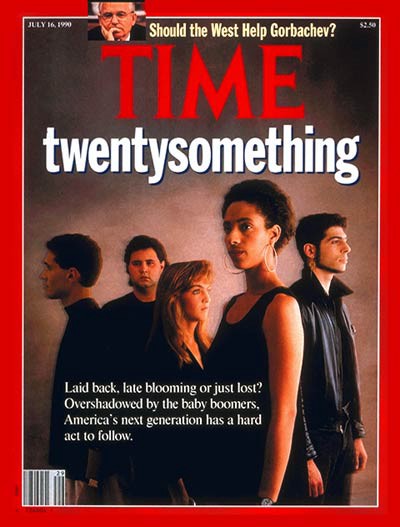

Meet the Permaslacks: Older Now, But Still Wearing The Same Clothes

Generational torsion is not a new thing. Each generation has one that comes before and then comes after. The as-they-are-known Greatest Generation butted heads with the Baby Boomers that grew their hair and attended, to a man, Woodstock. Then the Gen-Xers befuddled their folks by missing expectations, be they a gastroenterology practice, or dropping out of college, as applicable. Befuddling is what we do in that shear between the decades, as if it were a function of nature and not human nature.

And now, as Gen-X grows old enough to inherit the management of the forces that run the world, the Millennials (or Gen-Y, or Echo Boomers), as they are called, the immediately subsequent generation, are jumping the line in increments — see The Social Network, if you can bear to. The pie is not always inherited in an orderly fashion, and as mores change, matters of style become as important as matters of substance.

So basically it’s on.

I personally don’t have a dog in that fight. I’m firmly of a Gen-X age, but my ambitions do not lie in the field of owning and/or running things. And certainly, some of the traits laid at the feet of the Millennials befuddle me. But I’m not here to throw rocks. I’m here to look at the rock-throwers, or at least to further define the playing field.

Generations have an enormous number of actual constituents. For example, there are about fifty million American Gen-Xers. (And over seventy million Millennials, for what that’s worth.) So to speak of them as a “generation” is not entirely fair. For every member of the Greatest Generation that was actually great, presumably there are at least one if not two or three who were not actually so great. And in the same sense, a goodly number of Boomers had crew cuts or beehives and were not the best hippies in the world. It’s the same with Gen-X. In Gen-X, there are plenty who never went to a liberal arts school, plenty who never wore plaid ironically or had long hair not so ironically, and plenty who have never heard of DFW. In all cases, the members of the generation who do not have the iconic behavior patterns and style sense are kind of excluded when generational matters are spoken of. It’s the noisy signifiers that get all the ink. And the noisy signifiers of Gen-X are what we call “Permaslacks.”

This would not be the first nifty phrase coined for this demographic segment, and it certainly won’t be the last. Coin-phrasing is what we do. “Rejuveniles,” maybe you’ve heard of, or maybe “Grups.” Both similar, but both different from this. Rejuveniles and Grups are those of a certain age, Xers no doubt, who were (at the time) adopting the trappings of juveniles as a style. There’s something to that, but let’s look at only these Permaslacks for now.

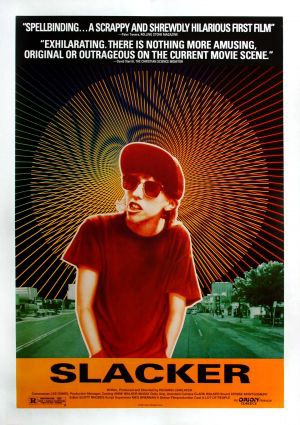

The derivation of Permaslacks is pretty obvious, and I guess we have Richard Linklater to thank for it, though Mr. Linklater has us to thank for himself, too, and mention surely must be made of

Superchunk. That would be just two of the many patron saints of the Permaslacks, who have absorbed culture like dry sponges over the spans of their lives, starting with the lunch boxes they took to school and the TV shows their parents watched and going forward from there. In fact, nostalgia is a constant backdrop for the PS, a nostalgia that isn’t even anything that grew over time: it was always there, and it was never personal. There was always a sense that there was a time before the then-current one. Loss? That there was some moment that would have been a more natural fit? At any rate, a sense of displacement, an acute awareness of being displaced, out of time, of being too late. Of being equipped to fully thrive in a paradigm that was the immediately previous paradigm. And this rolled through the years — while focusing on the immediately previous paradigm, another one thrives that will only be noticed once it’s over.

Which brings us to the act of joining. The PS does not do this, whether it’s a generational moment or a book club. It’s a source of consternation, those odd frozen moments when joining — that is, fully participating in an affinity group — is an option. There’s a feint, a half-hearted attempt, and then a purposeful retreat. It’s the converse of the Groucho-ism, about not wanting to join anything that would have him. More like, only wanting to have joined at some point previous. The PS is well-schooled in staircase wit.

The PS is easy to spot out in the world, as they more or less dress like kids. They keep grown-up clothes around, but they don’t spend money on them and Christmas only comes around once a year. They do clean up nice, as anyone does, but given the chance they will dress like it’s fifteen years ago (and it’s likely that the kid-clothes are actually fifteen years old, and were at some point au courant). Comfort is the key, both physically and spiritually, as is a somewhat superannuated sense of rebellion.

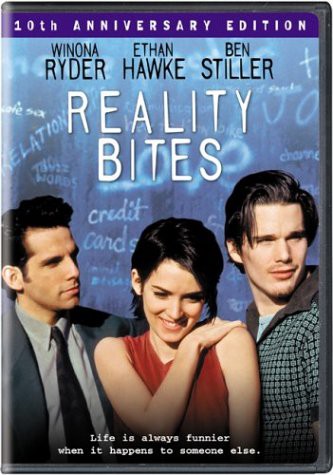

This is because lodged firmly in the center of the imagined power structure that the PS is reacting to, whether they know it or not, is the Man. Growing up with a pronounced strain of anti-authoritarianism, from punk rock (and post-punk rock) to movies (here’s only three of hundreds: Smokey and the Bandit, Porky’s, Platoon), the authority, the Man, was a laughable figure to be subverted, mocked or end-runned. The nirvana for the PS as a teen was Gettin’ Away With It. It was encoded in their neural pathways. And a whole bunch of the PS are parents now, and some actually the Man, creating an internal tension, a conflicted nature, a tentativeness. The PS still intuitively does not trust the Man even when the Man is staring back at the PS from the mirror — and even when the concept of the Man is itself hopelessly outmoded (which has never scared a PS away from anything).

Oddly, this anti-authoritarianism is partly inspired by a life of geekdom. The PS assimilated a good deal of low culture as high culture. Comic books were no longer funny books relegated to the drug store rack, and sci-fi films became big budget blockbusters, and yet there was still a sense of society’s nose turned up. And it was the PS that led the charge for legitimacy, as these art forms, previously aimed at children, were carried along into college and beyond. The enthusiasms of the PS die hard, and while snobs in their own way, they find what they like and are persistent in lobbying for it. And it is not ironic or purely nostalgic, this affection for Jack Kirby or Philip K. Dick, but rather an insistence on these objects’ inherent quality. Kitsch is not an affectation, it’s just that the gatekeepers hadn’t realized the good in the kitsch hidden behind the shabby.

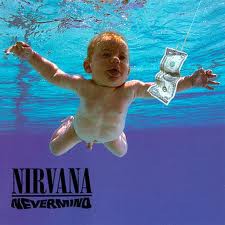

Music for the PS is almost too big to address as a separate issue. In fact, the great Where Were You When moment of the PS?

The death of Kurt Cobain, of course, and not because everyone was personally a fan (they sold out, you see), but because everyone was in physical proximity to at least one person who collapsed into heaving sobs. Music for the PS is not just a hobby, even for those who did or do not have bands, but a universal soundtrack of everything. You’ve heard the music. It’s still being played, and largely any band that meant something to any portion of the PS has reunited or never broke up (with the exceptions being the bands whose members have died, and the Replacements). This music is not of course exclusive to the PS, it’s everybody’s. It’s everywhere. And it’s where the PS derive their ethos of Do-It-Yourself from, after decades of watching their favorite bands Book Their Own Expletive Lives.

Ambition: that’s a good one. A defining characteristic, for good or bad. The PS maintains a very complex relationship to ambition. To all appearances, the PS exists in an absolute vacuum of ambition, replaced by a DIY complacency. Success would be fantastic, but the trade-offs for success are steep, and as each successive trade-off is refused, success is whittled down into an unobtainable thing that can only happen to them, unbidden. And to appear at all like the PS would welcome this success, to strive? That would be unseemly. Unseemly and something that will scare this unbidden success away. This mechanism is based on nothing but years of “intuition,” which is actually just a wet ball of entitlement and insecurity. There is no evidence whatsoever, objective or anecdotal, that any of these superstitions will have any affect over the success of the PS, but still: that’s how it works, and the PS has the haircut to show for it.

Not that the PS is not well-off. Most likely, they are. Either they have accidentally fallen into a career that is remunerative, or they have scrambled on the fringes of post-college careers so long that they are now the manager. They make the money, they pay their bills and their taxes. They do not have a second home, a boat, an annual vacation in the south of France. But they do all right, and they do so with a resigned loathing, because whatever they are doing for money, it is not what they want to be doing for money. They have unfinished novels in the desk, the band that still gets together when the other members can afford a babysitter. Whatever it is that puts food on the table, it is a “day job,” which, no, they have not quit yet, just as they have not quit calling it a day job, even though the window in which the day job gets to still be thought of as a day job is not open very much, and not getting any opener.

But the PS is not necessarily a lifer, as society is filled with former Permaslacks who have peeled off into legitimacy. And for the lapsed, quitting the slack is not a concession, it is a survival instinct. The post-punk anti-success sensibility propelled them quite nicely for a time, but the reckoning is abrupt and rude. And yet strangely comfortable.

There is an unkind word to describe the PS: misfit. It’s not a word that is used to describe the PS by third-party observers, but it’s the secret scarlet letter that is slowly choking the PS to death. Which is ironic, and not in the Alanis Morrisette sense, because the PS has proudly carried the misfit mantle, has actively propagated the impression of misfitism, for so long that it is no longer an affectation. It’s finely honed instinct. Look at the indications: the fashion sense frozen in time, the nostalgia-lock, the day job. This façade is not constructed painlessly or without sacrifice.

There are good qualities to the PS — sadly, the PS is too stuck in a feedback loop to have any awareness of these qualities. They’re vaguely aware, but swamped by sheepish self-doubt. And persistence. And self-doubt.

And that’s the fundamental difference that separates the PS from the Rejuveniles/Grups. The latter are formulated as valedictories and predicated on ample discretionary income, on success. For every one Rejuvenile/Grup, there will be two or more Permaslacks who raise their eyebrows at the vintage kicks and the $500 pre-distressed jeans as yet another commodification. The PS would never, even in rare periods of profligacy, pay a premium for the recreation of authenticity, because the act would be a contradiction. So respectfully I submit that this premise, while tangentially related, is not a reiteration of the premises that came before. In fact maybe those guys, the Rejuveniles and the Grups, were subgroups exclusive of what we’re calling the PS.

This is more of a confession than a scientific examination, obviously. Actually, this essay is more Exhibit A than anything else, because I’m certainly a member of this small group. These characteristics are generalities, and pretty specific to my socioeconomic circumstance and gender, and there’s hundreds of unifiers that I’ve left out, and hundreds of ways that the above qualities are not universal. But perhaps the most acute trait of the PS, of me, is the dogged insistence in one’s own uniqueness, that one’s story is an anomaly, a precious snowflake of a blessing/curse. And one of the hardest lessons to learn, above and beyond the array of consequence-of-one’s-actions lessons that fill a lifetime, is that, no, you are not unique. In fact, you are a demographic. I am not unique. I am a demographic. No matter how many years you spent convinced that you were trail-blazing, you were marching in lockstep with untold others. An army of non-conformists, all trying to be different in exactly the same way.

Which is why I find the Gen X (or the PS) v. Millennials conflict so quizzical. Maybe it’s just posturing, displaying one’s plumage at the watering hole, taking measure, but from the perspective of the PS, it might be fun to gripe and poke fun just for the sake of mischief, but totally not worth it to start a blood feud. With anyone. The PS is far too introspective for that. Unless, of course, the feud is with the Man, in which case all bets are off and the gloves are dropped and the Man better prepare to be gummed to death by out-of-tune guitars. Which may indicate that the prospects of the Millennials going forward is pretty damn good.

Annoying Jews and/or Asians Disturb Fashion Genius

There are conflicting accounts of the incident that IS ROCKING PARIS and MY WORLD right now, in which Dior’s John Galliano tussled with a lady with an ugly handbag and her Jewish and/or Asian friend. (Some reports say he said “anti-Semitic things” (though no one will say what!) and other reports say he called them “Asian.” Youch, harsh language, I guess?) The police arrived, and he was released this morning. How could ugly people in Paris get in the way of the designer of Dior? I hope they’re happy that he’s been “suspended” from his job. I smell a plot, as in, there’s always someone younger coming down the stairs who’ll get ugly Jewish and/or Asian people to get you in trouble.

Why Don't We Score Acting Like We Do Sports?

by Jeremy Keehn

There was a moment, early on filming day for the pivotal scene in Barney’s Version, when Paul Giamatti looked to me like an athlete preparing for a big game. As nattily dressed extras milled around the ballroom of Montreal’s Ritz-Carlton hotel, Giamatti, freshly planted in your father’s powder-blue tux, stood by the breakfast table around the corner. The producer, Robert Lantos, greeted him, and the two chatted a bit about the day ahead. Then Lantos, an imposing Hungarian-Canadian, abruptly gripped Giamatti’s shoulders, straightened him up, and gave him what looked like a Knute Rockne–style pep talk. Win one for the Richler, kid.

With that, Giamatti strode to the ballroom, where he spent the next few hours living out the moment when Barney Panofsky meets the love of his life (Rosamund Pike) at his wedding to his second wife (Minnie Driver). At an incongruous hour, Giamatti was pretending to be many things he was emphatically not: drunk, Jewish, a narcissist, a Montreal Canadiens fan, furious at his bride’s father, and totally besotted. Over and over, I watched him amble toward Pike and affect with complete, boozy certainty that she was the most fascinating woman in the world.

Standing between us was a few Internets’ worth of distraction — cameras, monitors, booms, director and ADs, plus your usual assortment of gaffers, best boys, key grips and exospherically high Oompa Loompas. Not to mention Driver, who watched the last take of the morning unfold on a screen, then leapt up, bridal curls in full bungee, and exclaimed “Horrible! Awful!” a dozen or so times on behalf of her wronged character. I couldn’t help but smile; Giamatti had clearly scored.

This was a few years ago, in 2009. Back then, the PR people touring me around the set were hopeful that their production of a beloved Canadian novel might garner some attention from the Academy. Its source material had the bona fides: the original Barney’s Version, Mordecai Richler’s last and most entertaining book, contains plenty of Oscar bait, including rich evocations of Jewish Montreal, 1950s Paris (changed in the film to 1970s Rome), anti-Semitism, romantic immorality, and terminal mental illness. And the film had Giamatti, the thinking person’s actor, a literate Yalie with many character parts to his credit, who should have been nominated for 2004’s Sideways, was nominated as a supporting actor for 2005’s Cinderella Man, and might have been, by the peculiar logic of the Academy Awards, due.

I’ve only been on film sets a few times, but I thought I could sense, watching Giamatti drop in and out of Barney, what made him Oscar-worthy. Nothing fazed him: not last-minute changes to shots, not a lengthy delay inspired by another actor’s antics, not people walking across his sightline off camera (a hanging offence for the hapless Loompa who drifted across anyone else’s). If this was a game, Giamatti was like Wes Welker, nimbly fielding pass after pass.

A year and a half later, I watched Giamatti’s performance in a downtown Manhattan cinema and still thought I saw an award-worthy performance buried in a very busy film. The Golden Globes agreed the following week, handing him their award for Best Actor in a Comedy. The Oscars, meanwhile, passed him over, short-listing Javier Bardem, Jeff Bridges, Jesse Eisenberg, Colin Firth, and James Franco instead. I wanted to call bullshit. I mean, come on. James Franco? He wasn’t even the star of 127 Hours — Danny Boyle’s split screen was.

If I wanted to make a convincing argument for Giamatti, though, it would be tough to know where to start. Go Google-hunting for the criteria the Oscar’s “multi-branch” committees use to create their shortlists, and you won’t find much of anything. Spend a little time on Rotten Tomatoes, sifting through the top critics’ takes on 2010’s best actors and actresses, and you won’t fare much better. With few exceptions, even the best reviewers point mostly to physical appearance, or lean on flimsy adjectives like talented, charismatic, affecting, convincing, and the ever-lame tour de force. You can find out from Roger Ebert that Jennifer Lawrence “embodies a fierce, still center” in Winter’s Bone, but not how she does so, or what a lesser actress might have done in her place. You can hear from Kenneth Turan that Colin Firth and Geoffrey Rush add “unlooked-for layers to a complicated human relationship,” but not what those layers are or how they add them. Anthony Lane’s review of Biutiful will teach you plenty about Javier Bardem’s strengths as sculpture, but precious little about his talents as a thespian.

This makes a certain sense: go back to the granddaddy of acting texts, Stanislavky’s An Actor Prepares, and you find the great director Tortsov giving a rehearsal of Othello his highest praise: “You who were playing, and we who were watching, gave ourselves up completely to what was happening on stage. Such successful moments, by themselves, we can recognize as belonging to the art of living a part.” If you’re a reviewer in thrall to a great performance, then your absorption naturally makes it hard to describe what you’ve seen afterward. Factor in word counts and the churn of deadlines, and no wonder we end up with so many tours de force.

But you won’t learn much about craft by trying to decode the Academy’s choices, either, though they were presumably scrutinized and debated at length. Patterns emerge quickly when you look at past nominees: the Academy adores above all the defamiliarizing leap (Charlize Theron’s hideous serial killer in Monster and Sean Penn’s mentally handicapped father in I Am Sam are the two strangest recent examples). To this it adds the great actor at his actingest (Pacino in Scent of a Woman), the overdue (Pacino again), the well liked (Sandra Bullock in The Blind Side), the bankable (Franco), and the obscenely pretty (I’m looking at you, Javier Bardem… why can’t I stop looking at you?). Filmsite’s exhaustive breakdowns emphasize the importance of the role: it helps to play a real person, or someone who dies, or someone with a disability or disease. It helps men to play old, and women to play young, or better yet to play a young floozy. It helps both to be white.

Perhaps, then, it’s time the Oscars began adopting metrics. In the acting categories, they might score basic markers of quality like range, depth, intensity, subtlety and bearing, then factor in more complex ideas like strength of cast or degree of difficulty. Still a subjective and flawed method, no doubt — I read that Malcolm Gladwell article, too — but better fodder for argument than we have now. (And though they would start out imprecise, the metrics would no doubt improve over time: hell, with video game, animation and robotics companies hard at work bridging the Uncanny Valley, we might not be far from outright measuring emotional affect. When that day arrives, I’ll be ready to get rich with my network of fantasy acting leagues. It’ll suck even harder to be this guy, though.)

Consider this divisive nominee in the best supporting actor category, for example: “It’s a measure of Christian Bale’s brilliant performance that the viewer can’t look anywhere else when ‘Dicky’ is on screen,” writes Joyce Carol Oates of The Fighter, exactly right save for the word brilliant. You could fairly give Bale a 10 for intensity, sure, but you’d have to balance it with a -105 for subtlety.

I’m not a statistician or a film critic, and I’ve never studied acting, so I’m hardly the person to create an elaborate system. As a fan, though, I’d enjoy making use of one. I watched or re-watched most of the year’s nominated and snubbed performances with the idea of a system in mind, and I thought it helped me better appreciate what actors do. For depth, Nicole Kidman, Michelle Williams and Colin Firth stood out. For range, Ryan Gosling and Kidman again. For intensity, Jesse Eisenberg, Jennifer Lawrence and Williams. For subtlety (i.e., best straight face during a gratuitous imagined lesbian scene), Natalie Portman.

In scrutinizing these qualities, I felt I got a sense of their component parts, too. Depth, for instance, depends heavily on how much an actor gets across in a glance. In The King’s Speech, Firth must repeatedly convey a singular pain; by the end of the film, his Stammering Prince Look is as recognizable to the viewer as the Art Shell Face is to an Oakland Raiders fan. You can practically see the imperial tonnes of pressure piled onto Firth’s quivering lip and terrified eyes. So yes, a 10 for depth. As powerful as the SPL is, though, the role doesn’t demand much range — I’d give it a 6 at most. (Really, they could have called the film The King’s Stutter, but I guess you don’t call attention to a one-note song by calling it “C.”) Nicole Kidman in Rabbit Hole was more of a LeBron-style cross-category killer, showing depth and range. Over the course of the movie, she’s at turns bitter, angry, sad, tender, near-crazy and then, finally, hopeful. And during her freighted conversations with the teenage boy who accidentally killed her son, she’s often several of them at once. An 8, easily, in each category.

When I watched Barney’s Version a second time, I still found Giamatti compelling, but felt I’d need a multiplier for degree of difficulty to make my case for him. There are certainly moments when he’s great by traditional measures — he’s Kidman’s equal at the moment when, in the aftermath of his first wife’s suicide, her father shows up in Rome. Up until her death, the movie’s tone has been exclusively comic, the girl, Clara, a stock banshee bent on emasculating Barney at every quip. When her father starts to ramble on about her long history of emotional problems, though, the camera cuts to Giamatti, and his expression starts to change. Barney recognizes something in the man’s evasion, and Giamatti’s gradual shift to pained incredulity tells you everything you need to know about Clara’s abusive upbringing, moments before the script hammers it home.

At other times, though, he’s in Bale territory. Through the first two-thirds of the movie, he’s given only a few brief, sporadic incidents to convey the onset of Barney’s dementia, and then suddenly he’s trashing a room because he forgot a phone number. Given that the film skitters across four decades, two continents, and three female leads, his performance simply can’t be as smooth as Firth’s. Where The King’s Speech is about one problem, Barney’s Version covers a half dozen, meaning Giamatti has the harder job: bringing cohesion to a complicated movie by finding and maintaining an emotional core. I’d rate the performance above average on the basics, but then I’d multiply for the challenge of playing Barney at different ages, in different locations, opposite different actresses, etc. etc. etc. Let’s see… (8 + 8 + 7 + 6) × 1.47 × 1.31 ×… carry the… fractals… well, I respect numbers, but like I said, I’m no mathemastician.

I want to call one in, though. I’d like a little more backup to help me explain why, the first time I saw Barney confess to the love of his life, Miriam, that he had cheated on her, I felt such deep empathy with the film that I spent its last twenty minutes thinking about my own life and loves. That scene felt to me like the full Stanislavsky: best acting because it no longer seemed like acting at all. I was satisfied then with the subjective experience of giving myself over to what was happening onscreen, but with the Oscars upon us and Giamatti not in the game, I want to see the numbers. I swear it ought to be him over Franco and Firth. For now, I’ll just say he was tour de forcer.

Jeremy Keehn is acting like a writer RIGHT NOW. He used to act like an editor at The Walrus. He pretends to blog here.

Photo credit: Takashi Seida/Sony Pictures Classics

Tie-Wearing Cat Makes Good Point

This should be required reading for anyone who is about to post an image macro to the Internet. I mean, it wouldn’t change anything, but it would at least make people stop and think for a second before they went ahead and cheezburgered. And maybe in that second they would lose their wifi connection or get distracted or something. It’s worth a shot.

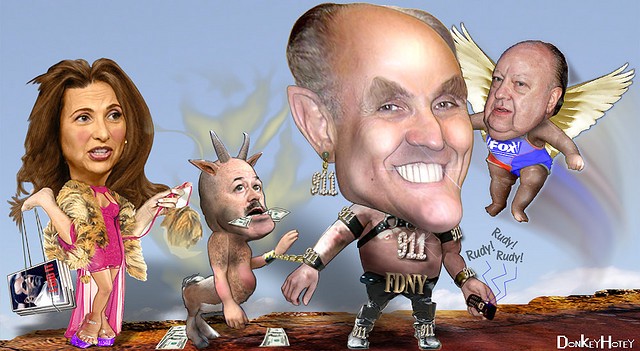

Could Roger Ailes Have Told Someone To Lie?

“Fox News Chief, Roger Ailes, Urged Employee to Lie, Records Show,” is how the New York Times headlines a story about how Ailes “encouraged [Judith Regan] to lie… to federal investigators who were vetting Bernard B. Kerik for the job of homeland security secretary” because Ailes feared word of Regan’s affair with Kerik would damage Rudy Giuliani’s presidential campaign (a feat that Giuliani proved quite capable of handling on his own, as it turned out). The whole thing is a bit of a trip down memory lane (I mean, when was the last time you thought about Judith Regan?), but, really, couldn’t that headline just as easily apply to every Fox News employee who has ever received a memo from Ailes?