Dad Rock

Dancing with Putin’s Secret Daughter

According to Reuters today, Russia is building a 1.9 billion ruble ($30 million) state-of-the-art center for the niche sport of Rock’n’Roll dancing just outside of Moscow. The center will be built with government money, which seems odd until you learn that president Vladimir Putin’s secret daughter happens to be very good at the sport.

Russia’s $30 million center for acrobatic rock’n’roll, sport of Putin’s daughter

“Secret daughter?” you might be saying. Reportedly, Putin’s youngest daughter Ekaterina has “not been seen in public since she was a child when her father first came to power 16 years ago.” But there is a Russian Rock’n’Roll dancer named Ekaterina Tikhonova who competed in the world championships back in October. When Russian news outlets asked the president if she might be his daughter going by a new last name, he declined to comment at the time, but there are non-Putin sources on record who say it’s definitely her. With me? ““““Secret””” daughter.

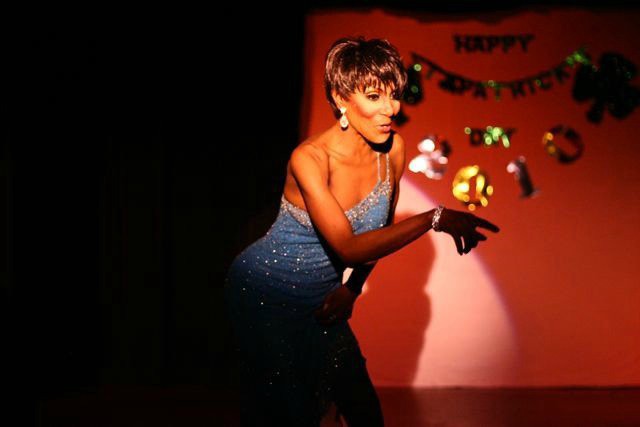

So anyway, Russia is spending $30 million on this new dance center, which seems like a big investment when you consider the supplies the sport requires. According to the World Rock’n’Roll Confederation, it’s a competitive type of partner-based dancing that has roots in Boogie Woogie and Lindy Hop. According to YouTube, it’s like the prom scene from Grease but longer. Here is Ekaterina dancing on a basketball court six months ago:

When a basketball court is not available, any place with a dance floor, sound system, and seating seems to meet their needs. Here are some dancers tearing it up in Western Poland during the 2014 world championships:

Ekaterina also reportedly holds “a senior position” at Moscow State University, and helps direct “a $1.7 billion plan to expand its campus.” Not to be paranoid, but is this? Starting? To sound? Like any father-daughter political duos??? In the news????? ? ? ?? Today?

Anyway, if you were waiting for a good time to take up Rock’n’Roll dancing, it appears the answer is now.

The Lady Chablis, After Midnight

At the memorial service for Savannah’s breakout transgender star

Befitting the Grand Empress of Savannah, the Lady Chablis memorial service lasted from before dusk until well past midnight. Family and friends and fans filed into the historic Lucas Theatre in downtown Savannah on November 5th to honor the transgender performer and breakout star of the book and movie, The Midnight in the Garden of the Good and Evil. She died of pneumonia in September, at the age of fifty-nine. In the lobby, a red urn containing her ashes was flanked by four of her sequined gowns. Inside the theatre, photos and videos of her looped on the widescreen, and more than a dozen speakers told stories of a diva, a generous friend, an electric entertainer. Afterwards, Club One, the gay nightspot that was her artistic home, hosted two tribute cabarets. “From the grave, she is making me put on this last big show,” said her longtime friend Cale Hall, a co-owner of the club. “That’s fitting for her.”

Before there was “Transparent” or Laverne Cox or “RuPaul’s Drag Race,” there was the Lady Chablis. She was a black transgender performer for decades before it was accepted as it is now, which is still not nearly enough. Famed drag queen Lady Bunny, who had flown in from New York, recalled the first time she saw Chablis. It was at a gay club in Chattanooga in 1977. “I had never done drag before,” she said, her signature big blonde hair coiffed in a black mourning veil. But when she saw Chablis and another entertainer, she said, “I knew that whatever they were, that’s what I wanted to be.”

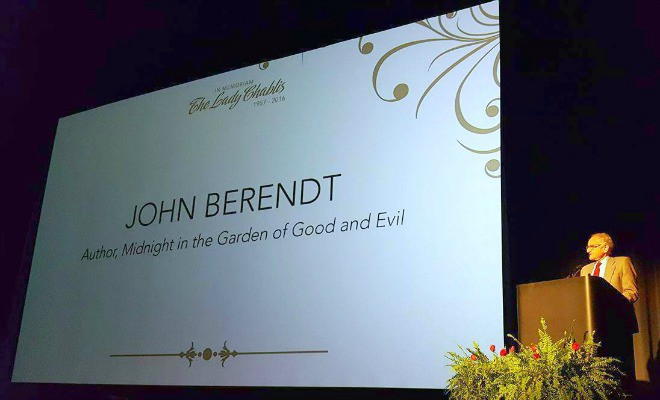

“Chablis was at the forefront,” John Berendt, author of Midnight, told the attendees. He recounted the day thirty years prior when he met Chablis in Savannah, after she invited herself into his car for a ride home. He wrote her into his runaway bestseller, which made her a star well beyond the club circuit. “She was one of the first transgender performers to win acceptance by a general audience,” he said. Afterwards, everyone had a Chablis story. People devoured the book, or they watched her steal scenes from John Cusack, or they saw her on “Oprah.” Tourists and suburbanites and bachelorette parties poured into tiny clubs to see her.

I knew Chablis because she was my childhood neighbor. My father was her landlord for nearly twenty years. He and Chablis lived in a row of aging, one-story brick houses on a block in West Columbia, South Carolina. My dad moved there after my parents’ divorce, back into the house he grew up in, where I would spend weekends and summers. Our family had long rented out the house on the corner as an income property. Throughout the 1980s, the lease had been passed down through word of mouth among a circle of lesbian couples (whom the neighbors called “roommates”) and who were mostly artists and performers at a local comedy club. Through them, the rental eventually found its way to Chablis, who lived there longer than anyone else.

My father looked like an unlikely ally: a ruddy-faced welder and pipefitter who rarely dressed in anything but blue coveralls, whereas Chablis, even in casual clothing, exuded elegance. My first clear memory of her — I was likely ten or eleven — came when I tagged along as my father fixed the plumbing under her sink. Racks of clothes filled the kitchen, stuffed with ball gowns and cat suits, full of sparkle, leopard, and faux fur. She was likely getting ready for a show, and packing up what she needed. This was right around the time the book came out, and though we knew she was a performer, we had no idea she was becoming famous. We wouldn’t know until sometime later, when Dad caught a glimpse of her on the “Today” show.

Chablis had a wicked sense of humor. She took great joy in her ability to rib my father, and most anyone, with bawdy jokes. In recent years her constant companion was a fluffy white dog — a maltipoo — who was hyper and ill-behaved and adorable. She named him Cracker. It tickled her to no end to let him run loose in her yard, and call out after him — “Cracker! Cracker!” — repeating at a loud decibel for her mostly white, grey-haired neighbors to hear. “She could defuse racial or trans tensions just by being herself, just with her humor,” Lady Bunny said at the memorial.

Her monthly cabaret shows at Club One, where she had been performing since 1988, were full of camp and glamour and wigs. But at home, I most often saw her in no make-up, with pixie-cut hair, and her corset-sized figure draped in a t-shirt. There, she was simply Brenda Dale Knox, as her friends would say, and not the stage presence of the Doll, the Empress, the Lady Chablis. When she found out I wanted to be a writer, she said I should write a book about her and call it, A Black Boy in the South Who Likes to Wear Dresses. I told her that title might be a little long. She ended up writing her own memoir, suggestively called, Hiding My Candy. But for all her gender-bending talk, she lived as a woman — a point too often missed during her media heyday.

Chablis hated labels. She defied gender essentialism, even as many reporters tried to make it an issue, labeling her derisively, and sometimes for comic effect, in headlines and copy as a “he/she.” Now it seems almost standard for the media to talk about gender non-conformity, but back then the public’s insistence on boundaries only made Chablis more apt to break them. She came to loathe the label of drag queen. “The word ‘drag’ offends me,” she once said in a newspaper interview, adding, “I live as a female.” She ultimately preferred one label, and that was her legal name: The Lady Chablis.

Movie stardom did not protect Chablis from a certain kind of peril. Then as now, renewed attention to the trans community brought with it greater awareness and understanding, but also the threat of the wrong kind of attention. “I couldn’t go to Big Lots or anywhere,” she once told a Savannah reporter. “That person behind me might be a fan but it could also be some redneck following me. Not everyone is into the Lady Chablis.” After years of living in Georgia, she moved to South Carolina, and commuted back for gigs, partly because her new city offered the anonymity that Savannah did not. “I picked West Columbia because it’s the last place anybody would expect to find me,” she quipped to our local newspaper after the book hit the bestseller list. She often talked about the movie outing her: After, strangers knew her as a “transvestite,” not as a woman they passed on the street. It made her a target.

Her health deteriorated. There are few paid sick days for club performers, and there is a notorious lack of steady work for trans people. Money came and went. For years, she paid her rent in wads of cash from her tips, until my dad drove her to the bank to open a checking account.

It would be wrong to overstate my relationship with Chablis. At its root, she and my father had a business relationship, which I inherited. She was my neighbor, and I knew her when I was a child. And when I was no longer a child, I still reverted to a shy state of awe around her. Like many others, I was lucky to have known even glimpses of her. My father died in 2012; there were medical bills and debts to pay, and his home was in foreclosure. I had to sell the little house on the corner. Chablis didn’t want to leave, and I didn’t want her to go. For a long time, my father had wanted her to buy the place, but she couldn’t, and so by the end of the following year, she moved out. When I drive past now, there are tricycles and a trampoline outside. Someday, I think I will stop and knock and tell them about the people who used to live on their block, in their houses. I will tell them about The Lady Chablis.

I took for granted that there would be more time, and that I could always find her at one of her shows. I imagined a road trip to Savannah, a reunion after midnight, at the club. There would be time to tell her again how sorry I was she couldn’t stay in the corner house, how I regret how it all ended. That is, in part, how I found myself in the basement of Club One on a Saturday at the reception, where guests ordered drinks and served themselves jambalaya from the bar. Nearby sat Chablis’s sister Cynthia Ponder, the spitting image of her. At the memorial, Ponder said she believed God had a plan for her sister, that she was to give to the world something, even through the struggles. I asked her what it was like growing up in Quincy, a rural community in the Florida panhandle. “We were from a very small southern town,” she said, “but you can’t hold someone like her back from being their true self. I’ll put it like that.”

Chablis was stubbornly, exuberantly herself. There’s a magnetism about that kind of confidence, about seeing someone with such an unabashed sense of self, no matter who is watching. And watch they did. The movie and the book are still everywhere in Savannah, in hotel brochures and on the tongues of tour guides. Tourism skyrocketed for the city, and locals have John Berendt to thank. But they also owe gratitude to the cast of gay and transgender characters at the book’s center, a point that conveniently does not make its way into many official tourism talking points.

“She put Savannah on the map,” Destiny Myklz (pronounced “Michaels”) told the crowd at the Lady Chablis tribute show. Myklz emceed the Club One cabaret, which included lip synch performances from the club’s regular line-up, many of whom worked for years alongside Chablis. There was a country number to a Sugarland song, and a dance number to a Beyoncé medley. There were mile-high wigs and contour make-up. There were sequins and gowns and teensy underwear and knee-high boots. The show, as Chablis might have said of her own, “was not a Disney production.” At the end of the set, Myklz thanked the audience for helping them honor the Lady. She lifted her arm in the air and pointed her hand to the sky, saying, “This one’s for you, Doll.”

Tiffany Stanley is a writer in Washington, D.C.

The Editor The Public Deserves

Chris Lehmann on the role of the media

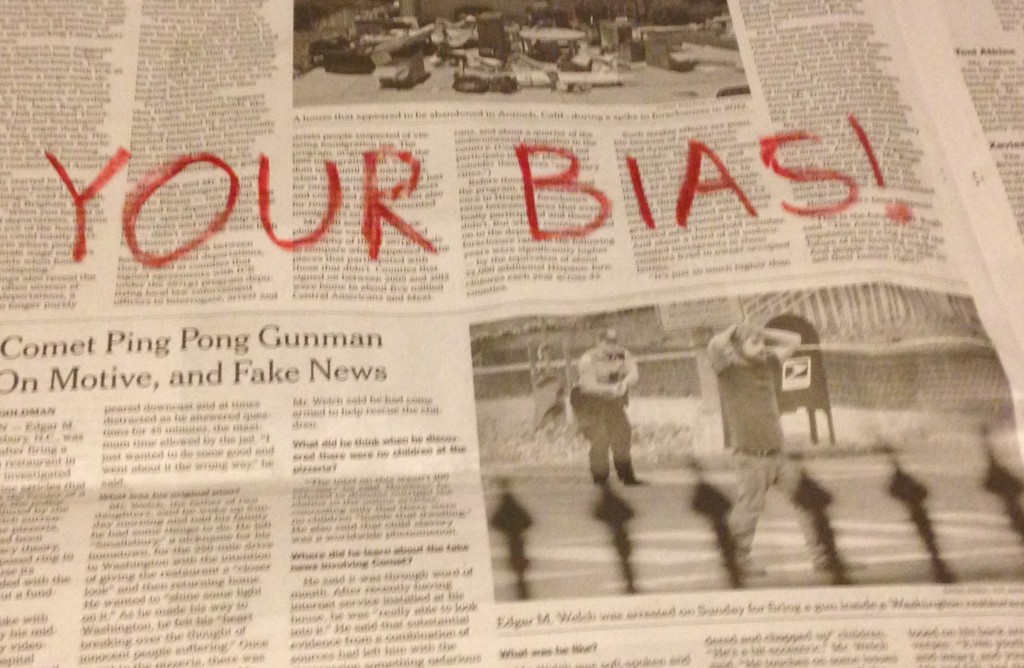

“Times figureheads like [Bill] Keller and [Liz] Spayd are apt to roll over at the first right-wing charge of rampant liberal bias because they themselves are ill-equipped to face down right-leaning challenges to their journalistic legitimacy. This is not so much because they are ensconced in their elite bubbles of liberal opinion and are terrified at the prospect of sustained contact with anyone professing to be an emissary from the Real America of NASCAR, megachurches, and Trump Worship. No, the real problem here is that these people are journalists second, and corporate managers first. And the thing that truly terrifies corporate managers in the brave new digital era of our news environment is anything resembling the defiance of consumer prerogative. Put another way: as shops like the Times continue to hemorrhage readers and ad revenues at an historic clip, their managers will rally by instinct to the ritual protection of the injured sensibilities of any and every reader demographic.

Do I exaggerate?”

He does not:

Manhattan-bound E train

Illustration: Forsyth Harmon

You were sitting next to me, all of us packed tight and untalking on this E train, but I only noticed you when the handle of my umbrella got caught in your bag. It was that sort of day, a day of encumbrances, barometric headaches, chafings. A day that smelled like petrol puddles up there, and wet dog down here where bits of ourselves kept getting caught in bits of each other: big damp backpacks in faces, unsheathed umbrellas dripping down trouser legs, wet ponytails flipping against cheeks. You and I apologized to each other in unison, gave the quick smile in unison.

You had long, very red hair, and you were wearing a very purple top. This chromatic discord was striking. A bold choice, this bold color — and it was clear you were anything but: awkwardness emanated from your shoulders, elbows, knees. I had a feeling, in other words, that the color clash thing was an accident rather than a choice.

Shyly, while I pretended not to look, you began pulling from your bag something plastic-wrapped, something that made that delicious, secretive sound. My friend had just been telling me about the YouTube world of ASMR. I had rabbitholed, briefly, in this realm of women posting high-sound quality videos of themselves whispering, crinkling, rustling, and gently tapping things. Rabbitholed even longer, in the world of comments below, where people divulge their delightful tingles, sudden sleepiness, massive boners, or sudden urge “to touch everything in the most fragile manner.”

When I heard the soft rustle of the thing in your bag I have none of these urges. Instead, I realized this is how dogs must feel when they see a squirrel: for half a second, I’m nothing but a limbic system barking the monosyllable, snacks? Honestly, what could be more interesting than a stranger’s subway treat, slowly drawn from a bag? I couldn’t take my eyes away. When I saw it I wanted to shout or shake you. Your snack was an endive. One, chilly sad pale spear of an endive, withdrawn slowly from its baggie, like some miserable bit of evidence. Worse, you didn’t even chomp it. Instead, over the course of three or four stops, you plucked off one stiff petal at a time, and nibbled furtively. You were touching it, I realize, in the most fragile manner.

By the time you got off, hastily packing away your half-eaten vegetable, I no longer wanted to shake you. I think, instead, that I wanted to hug your awkward bones and give you a donut, something fat and glazed and luscious that you could eat in three big bites.

Takuya Matsumoto, "Black To Blue"

When did we stop thinking in decades?

I was at a restaurant yesterday where I guess they had put on the “Alternative Hits of the ‘90s” playlist, because as soon as I sat down it started with Toad the Wet Sprocket’s “Walk on the Ocean” and went from there. (If you remember the ’90s as a participant you will now have Toad the Wet Sprocket’s “Walk on the Ocean” stuck in your head for the rest of the day. I’m sorry about that but I’ll be damned if this is a world I will walk through alone.) Round about the time Better Than Ezra’s “Good” came on — again, apologies — I got to thinking: When we were in the ’90s, we were super-conscious about it being the ’90s. “This is how we do things now that we’re in the ‘90s,” we’d say, as we spilled coffee on our flannel shirts and stopped playing Tetris on our Game Boys long enough to call our roommates on landlines and remind them to drive by the grocery on their way home to pick up some clear beverages. “This is the music we listen to during these years of the ‘90s,” we would tell our friends as another sludgy-sounding Seattle rip-off act came over the speakers as we checked out the zines at the used CD store. “Everything’s different now, here in the ‘90s,” we would remind ourselves as we drove our punk-rock Subarus to our McJobs etc. I was also fully conscious during the entirety of the ’80s and there was a similar, if more mercenary, awareness at play; my memories of the ’70s are cloudy and tangential at best but all the histories of the era I’ve read indicate that those perceptions were also present. And don’t let’s get started on the ’60s because those people haven’t STOPPED taking about it and won’t until they finally die, even though every fucking thing they’ve done to the world has been terrible and poisonous and the fact that they are leaving on a legacy of making Donald Trump the last boomer president is a shame that would silence any decent generation for the remainder of their days.

In any event, was there any sense of decade-consciousness after the ‘90s? I feel like in the aughts, which we didn’t really settle on as a name until way late in the era, everyone focused on the turning of the millennium and then forgot about it. And the teens, can you point to anything specifically “teeny”? Maybe we were too busy getting through the financial crisis? Maybe the fact that the ’00s and ’10s don’t lend themselves to sonically pleasing nicknames has us less likely to conceive of them as specific chunks of a defined era. Or maybe, and this is the theory that I am partial to, the way the Internet has made it every era all the time everywhere now keeps us from thinking in this admittedly reductive fashion about our specific period. (Given how little time we’ve got left this is probably not a bad idea.) I can’t say for sure, although when I brought it up with a friend last night I was told it was a topic I should absolutely write about, which, on reflection, was less an expression of interest than a desire to shift the conversation to something else and also a sign that my friend does not have my best interests — or yours — at heart.

Anyway, think about it and get back to me. In the meantime, here’s some music from NOW. Enjoy.

New York City, December 7, 2016

★★★ The ringer in the alarm app had been turned low and there was nothing in the dark morning, after the sloshing rainy night, for the mind to grab onto on the way up to rousing itself. The rain had given out but the gray stayed. A wet earth smell hung over the forecourt. By midafternoon the cloud cover overhead was letting blue through, but the gloom below lingered, undiminished, a while longer. Then the clouds took on shapes and west-facing glass brightened, and in minutes the proportions of blue and gray had reversed themselves.

Why Is Everyone So Angry?

Pankaj Mishra on the limits of logic

“Ressentiment — caused by an intense mix of envy, humiliation and powerlessness — is not simply the French word for resentment. Its meaning was shaped in a particular cultural and social context: the rise of a secular and meritocratic society in the 18th century.… [P]eople in a society driven by individual self-interest come to live for the satisfaction of their vanity — the desire and need to secure recognition from others, to be esteemed by them as much as one esteems oneself.

But this vanity, luridly exemplified today by Donald Trump’s Twitter account, often ends up nourishing in the soul a dislike of one’s own self while stoking impotent hatred of others; and it can quickly degenerate into an aggressive drive, whereby individuals feel acknowledged only by being preferred over others, and by rejoicing in their abjection. (As Gore Vidal pithily put it: “It is not enough to succeed. Others must fail.”)

Such ressentiment breeds in proportion to the spread of the principles of equality and individualism.”

A Poem by Ed Skoog

Looking for Work

In the city no tree is too small

to escape the human alphabet

and yet one without a job

is kind of invisible. What job.

What tidy bit of formal activity.

I float into all the windows,

follow all cars home and inhabit

the secrets my neighborhood carries

When you’re unemployed in a plaza,

you have entrée to the multiple affairs,

the entreaties, the escapes, the wrapping-up,

the years-later. I used to sit at a counter

and dust the classifieds with my toast crumbs

drawing circles like one deciphering glyphs

by lantern in a tomb, and walk away cursed.

Under the weight of their credentials

my leg broke in five places. Over here,

their statue of the Buddha, over there,

the open letter, and probably nuclear

submarines glide under the sunset,

one might guess from the short life span

glowing around each of us. Meanwhile

a stranger plays the gold piano she wheeled

under the lindens. Gold is its own concordance.

I play the most delicate balalaika, and bike

all night with a samovar balanced on my handlebars.

I think I remember work, stifled yawns,

how a rivet pulls the metal sheets together

like near-strangers clutching at last call.

My advice is to be survived by a hymn.

Put allegories in charge and wait for loss.

Ed Skoog is the author of three collections of poetry, Run the Red Lights, Rough Day, and Mister Skylight, all published by Copper Canyon Press. He is poetry editor of Okey-Panky and co-host, with novelist J. Robert Lennon, of the podcast “Lunch Box, with Ed and John.”

The Poetry Section is edited by Mark Bibbins.

It Can Always Get Worse

The U.S. is rich and powerful, but its luck could run out—or worse, get tossed out the window.

Often when discussing the economy or politics, people will say things like, “Who cares! Throw all the bums out! It can’t get any worse!”

This is, unfortunately, extremely incorrect. It can always get worse. This is especially true in the United States, which is perhaps the luckiest danged country in the history of the world. It is definitely the richest and most powerful danged country to ever exist.

Here’s a screenshot from one of my favorite Wikipedia pages ever, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_GDP_(nominal), which measures the total size of every economy in absolute international terms.

As you can see, we are pretty far ahead of the pack. Second place here, the EU, is actually a big group of countries all added together, and third place has almost 1.4 billion people spreading much less money around. There are 194 countries on that list. Look at these poor guys:

But of course, those places are basically empty. That list is good for getting an idea of geopolitical economic power, but to get an idea of what life is like on average for people in each country, I often turn to my other favorite webpage, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_GDP_(PPP)_per_capita, which divides the size of the economy by the number of people and adjusts for how expensive life is there. Again, we’re doing pretty dang good:

Please note that the countries above us are mostly fake places with no people, maybe just a bank or an oil field with a weird flag sticking out, or Norway. Brooklyn has more people than Qatar; that place doesn’t count. Out of all the countries with significant populations, we’re at the very top of the heap. Then right behind us, in order, we have Saudi Arabia, the Netherlands, Austria, Germany, Bahrain, Denmark, Iceland, Sweden, etc. Other really rich guys.

What is life like in normal countries, or poor countries? Here’s things in the middle:

China, by the way, is number 74 with $14,239 annual GDP per capita, adjusted for PPP, so they’re just a tiny bit better off than the median. China, the world’s most populous country, has done quite well in the age of globalization, which means that they have gone from being very, very poor, to just OK. And here’s the bottom:

Americans are 5 times as rich as citizens in the world’s median countries! And compared to Earth’s actual corners of poverty, we have 55 times as much.

Let’s try to think which of the following two scenarios is more likely. Are U.S. citizens 5 times as smart, productive, and deserving as the average human being? Or is it perhaps that we have been the major beneficiaries of a deeply unequal, historically contingent, fragile global system that has been carefully constructed over many decades? Maybe things can definitely get worse? From the perspective of any other country on Earth, the notion that our exorbitant American privilege is simply the natural state of affairs — the default settings on the world’s operating system, which we can just reset to Great Again at will — is laughable. It’s not only that we could lose our power and wealth. One could even make a convincing case that we should.

When we fell into a position of unprecedented power after World War Two, thousands of people worked carefully for decades to create trade and diplomatic ties around the world. Maybe setting fire to that entire edifice — which the U.S. built in its own image, often employing violence to do so—might not magically lead to outcomes that are good for us?

We know that life sucks very badly, and on top of the cruel burdens of existence itself, the huge amounts of money that flowed into the U.S. during the globalization of the last three decades was distributed very poorly. Economic elites took almost all the gains for themselves; a credible plan to now spread that wealth around and take advantage domestically of our enormous economic power would be welcome. At home, we do use our national wealth in bizarrely inefficient ways. Healthcare would be nice, for example. I’ve spent the last few years reporting on politics and economics in South America, and it’s been very clear down here recently that just because a society is unequal and dysfunctional, shaking things up does not necessarily lead to improvement.

By any broad historical standards, the era of peace, democracy, prosperity and global dominance that the U.S. enjoyed from 1945–2016 seems like an especially lucky break. It would be one thing if our political leaders presented a concrete plan to improve upon existing globalization, or use its resources to expand public services. It’s entirely another to go to battle with all of our partners and assume that by being “tough and smart” we’ll put it all back together again, even better. Political systems do explode — in fact, most of the systems in history have done just that — and just throwing a bomb into the engine rarely fixes your car, no matter how legitimately upset you are with where your car is going, or how fun it may sound to do.

In 2010, a literal clown popularly known as “Tiririca” ran for Congress in Brazil, riding a wave of anti-political sentiment and propelled by two snappy TV slogans. The first was “What does a Congressman do? I don’t know! Vote for me and I’ll tell you.” The second was “Vote no Tiririca! Pior do que tá não fica!” It rhymes and sounds nice in Portuguese but in English it’s best translated as “Vote for Tiririca! It can’t get any worse!”

This message resonates. He won more votes than any other candidate running for office. He got so many votes, Brazilian electoral rules allowed him to actually bring four other men (in Brazil it’s almost always men) into office to serve as Congressmen along with him. At the time, bien-pensant voters lamented that their country could fall for such an infantile rebellion and asked if it was proof that Brazil was an immature banana republic. Others said maybe he responded, in an insane way, to a real disconnect from the political system.

Brazil was very far from perfect in 2010, but viewed from the perspective of 2016, the promise that things could not get any worse now seems like a cruel joke. In 2010, the economy was growing at 7% per year, unemployment was at historic lows, and Latin America’s largest country elected its first woman president. In 2016, the country is in its worst recession in a century, unemployment is at 12%, and that woman, Dilma Rousseff, was impeached this year by a group of men whose new more conservative government is plagued by accusations of corruption.

I interviewed Tiririca in Congress in 2013, and found him a likable and clever guy. Unlike other clowns elected to major office, he immediately set about proving he was serious about his position, and made sure to attend every legislative session. Ironically, his major role in office has probably just been to lend support to more powerful, traditional factions around him. I remember the gasp that when up in Congress this year when he unexpectedly voted to impeach Rousseff, but even then, he was just switching sides from one powerful faction to another.

Clearly, Tiririca didn’t ruin Brazil himself. But the same broad anti-political sentiment that brought him to power was arguably also behind the explosion of protests in 2013 (clearly inspired by the countries of the Arab Spring, which now serve as some other pretty stark reminders that things can go from very bad to very worse). Those protests were followed by a questionable handover to men proclaiming loudly they will do the exact opposite of what the protesters asked for by cutting basic public services.

So what’s the lesson? It’s if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it? No, not exactly. Maybe just, “Even if it’s broken, try to fix it instead of angrily destroying it.” Perhaps it’s just that successful revolutions require tight coordination and a dedicated game plan. If there is indeed a careful road map prepared to lead us from 2016 politics to some shining American future, we certainly haven’t seen it.

In 2013, incoming White House chief strategist Steve Bannon reportedly told The Daily Beast, “I’m a Leninist…Lenin wanted to destroy the state, and that’s my goal, too. I want to bring everything crashing down, and destroy all of today’s establishment.” If anything, Leninism was about strict organization to seize power and quickly create a new state. But this dude is talking about the final scene from Fight Club. Someone cue the Pixies.