Six Things I Have Inadvertently Consumed

1. An Unknown Quantity of Pennies, 1986: My older sister and I are a year and a half apart. So the age at which she was ably walking on her own, I was in a hand-crank baby swing. As the story goes, my mom had stepped out of the room to answer the phone and returned to my sister feeding me from a jar of change in time with the swing — every time I came forward, she’d place another penny in my mouth. My mom didn’t worry too much because, as she says, “You didn’t jingle, so we assumed you’d be all right.”

2. Liver, 1992: My mom did an excellent job of making sure that my sister and I didn’t grow up to be picky eaters. Indeed, as an adult I maintain that I’ll try anything that isn’t brains. As kids, though, she sometimes had to resort to more creative methods. After we flat-out refused the liver and onions on our plates, she put it in a blender, liquefied it, fried it, and served it to us as “Pancake Meat.” Which, apparently, we loved and requested often.

3. Horsemeat, 1999: My middle school French Club went to Quebec City for the Winter Carnival, and somewhere between the snow sculptures and ice skating, I ordered a burger with a funny sounding name. What I understood to be a type of cheese my French teacher later informed me meant “ground horse.” Delicious, though I wonder how I’d feel if I had ever wanted a pony. Also, not the last time I’d be tripped up by French words.

4. Extremely Cheap Tequila, 2005: The only thing worse than shitty tequila is unexpected shitty tequila. Somewhere deep in the 30s of a power hour, my shotglass of beer was replaced by a shot of below-the-bottom-shelf-quality tequila. I drank it, but got some accidental revenge on that prankster by horking in his bathtub somewhere in the 40s.

5. A Crab Shell, 2007: At a sleazy-chic diner with my sister, I only noticed that something was wrong when she pointed out that cream of crab soup usually isn’t crunchy.

6. Brains, 2010: Hey, remember above when I said I’d try anything that isn’t brains? That was shot to hell at a fancy restaurant in Baltimore on Christmas Eve, when my sister (who, I am realizing, is a disturbingly prominent figure in this list) ordered the cervelle de veau and I, unknowingly, stole a forkful then, on the way out, asked the waiter what ‘cervelle’ meant. Brains. All brains. Unavoidably brains. Couldn’t even pretend I had eaten a gland. Brains.

(Items that did not make this list include: a cicada, an unknown quantity of pot-laced butter before a geography class, a postage stamp and the contents of at least three fortune cookies.)

Victoria Johnson is a cartographer and this is her Tumblr.

Photo by Pia Gaarslev, via Wikimedia Commons.

Other Comedians Aflac Could Hire To Do The Voice Of The Aflac Duck

1) Robin Williams

2) Whoopi Goldberg

3) Dane Cook

4) Pretty much any other comedian — or, really, person of any profession whatsoever — who can make his or her voice sound somewhat like a duck.

Weird Mystery of the Day

Serious question: Why are there so many pictures of Janet Jackson on Marion Barry’s facebook page? http://on.fb.me/g1wX6yTue Mar 15 19:30:06 via web

AlanSuderman

AlanSuderman

Rebel Libyans Stalling While the World Debates

Word that someone flew a plane into Gaddafi’s palace is still but a word. I think we’d all love to hear more about that, should it have happened! Otherwise, back in Libya, well… “Libyan rebels are retreating from the strategic town of Ajdabiya under heavy bombardment by Muammar Gaddafi’s forces.” Anti-Gaddafi forces seem to only hold three cities, and they’re isolated from each other; and government forces are trying to beat down the road to Benghazi, which has about 2/3rds of a million people. What is happening there is truly terrible. And what will happen if the revolution really does fail is even worse: two defeated generations dead or rotting in jails. All that being said, what would foreign intervention do? And… by whom? That said, it’s not over yet.

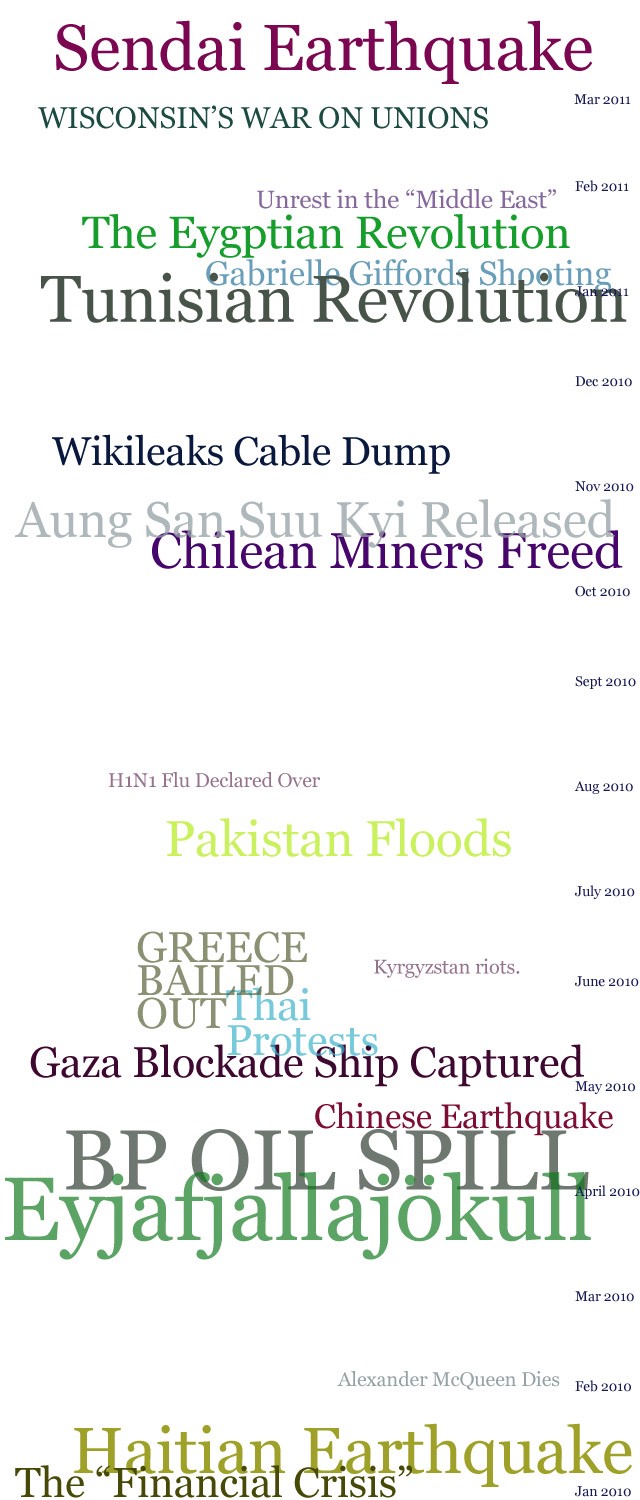

2010 and 2011: To What Were We Paying Attention?

I was just asking someone: what was that thing that happened, that then everyone stopped covering/talking about/reading about Haiti? Here’s a chart of what we’ve been giving our eyeballs to over these last 15 months.

TechCrunch Awesomely Gives Giant Finger to AOL

This is terrific. It warms my heart! TechCrunch just took a big chomp out of the suits who asked them to “tone down” their coverage. They’d interviewed the makers of The Source Code, and then actually rather insightfully written about how the film was “trying to target” techies and the tech press. But the AOL Moviefone people who’d set up the interview were not happy and came crying to Techcrunch — which is, still fairly newly, owned by AOL — who then promptly told them to f off: “What I didn’t understand when writing my candid opinion about the movie and its marketing strategy was that Summit thought that by inviting me to their party they were basically buying a puff piece.” Oh yes! Welcome to the dark world of entertainment coverage. You think tech or politics is bad, you ain’t seen nothing.

ACORN Still Up To Its Filthy Old Tricks!

“In November of 2009 we found 52% of Republicans thought ACORN had stolen the election for Barack Obama in 2008. Now only 25% think the organization will steal the election for him again next year.”

— What are you even supposed to make of this? Quick, everyone find your long-form birth certificates!

Our Debt: Why Rich People Should Be Worried Too

by Carl Hegelman

Back in the days before the great bull market began to charge in August of 1982, there was a soothsayer called Joe Granville. He was the Mad Money Jim Cramer of his day, a showman and exhibitionist whose performances included walking on water (across a swimming pool in Tucson, dressed in a tuxedo) and a piano-playing chimp. Despite that his demeanor wasn’t what you would expect of a great financial brain, he attracted a large following of investors for his $250-a-year financial letter (about $615 in today’s money), partly because, as People magazine explained, he had called four major stock-market turns in two years. His reputation grew to the point that when he issued a “sell everything” fax to his premium subscribers in January 1981 the market dropped 2½% on its busiest trading day to that point in history.

For every big financial turn, there’s at least one hero who saw it coming. It’s not surprising, when you think about it. Given the number of promoters airing their opinions, it would be surprising if someone, somewhere, hadn’t called it, maybe even three or four times in a row. It’s like the monkeys with the typewriters. The surprising thing isn’t the occasional masterpiece. It’s when the same lucky monkey who wrote Taming Of The Shrew then proceeds to peck out Two Gentlemen of Verona and Love’s Labour’s Lost. And, sure enough, Joe Granville’s reputation didn’t survive the Great Bull. Apparently, he’s still in business, but I read somewhere that over the past 25 years his recommendations have lost an average of 20% a year. No word on his piano-playing chimp.

There are various heroes for the financial crunch of 2008–10; such as Robert Shiller of Yale, who called both the dotcom and the housing crashes, and Meredith Whitney, the banking analyst formerly at Oppenheimer who first exclaimed, in October 2007, that Citigroup was wearing no clothes (and who, by the way, is now predicting a meltdown in the municipal bond market). Perennial doomsayer Nouriel Roubini of NYU is also often cited, although he was already something of a stopped clock by 2008, more focused on the trade deficit with China than on the exponential rise of house prices.

Lately, the economic duo of Kenneth Rogoff and Carmen Reinhart have become talk-worthy because of a series of studies of past financial crises focusing on the dire consequences of having too much debt. Their most recent paper on “The Aftermath of Financial Crises” caused a stir because it’s telling us that running up bigger deficits will only prolong the problem, a prescription that goes against the current policy of deficit-financing backed by both political parties — whatever they may say to the contrary — in the recent tax-cut-extension act. Probably nobody disagrees with Rogoff and Reinhart that our debt is a problem, but how big a problem is it and why is it a problem?

Well, if you add up $14.5 trillion in mortgage debt, $14 trillion of national debt (Treasury bills and bonds), $2.5 trillion in consumer debt (credit cards, student loans, car loans, etc.) and $3 trillion in state and municipal debt, you get to around $34 trillion. Given that we have about 140 million people working right now, that works out to about $240,000 for every working stiff in the country.

The median household (about 2.5 people) in the US has an income of around $52,000 a year, and that’s including things like unemployment and Social Security benefits.

To pay back $240,000 at five percent over thirty years would cost this hapless worker about $1,300 a month or $15,500 a year. Obviously, that doesn’t leave much for spending on stuff. Which in turn means companies don’t make as much stuff and don’t need to hire as many people, which means fewer paychecks, which means… the debt makes it much more difficult to pull out of the slump.

According to Rogoff and Reinhart, unemployment rises by seven percentage points after your average financial crisis — we’re at about five so far — and the employment down-cycle lasts more than four years. House prices go down 35% over six years and stock markets go down 55% over three and a half years. Per capita real GDP goes down 9% over almost two years (ours went down about 4% and has just recovered to the level it reached in the fourth quarter of 2007). These are all average numbers for post-WWII crises. During the Depression, the United State’s GDP per capita went down a lot more — almost 30% — and bottomed out after four years. And because tax revenues go down when nobody has a job, government debt goes up — by an average of 86%. Which, of course, makes it that much harder for the economy to climb out of the swamp. Since March 2008, the government’s debt has so far increased about 49% — and it’s still climbing quite rapidly.

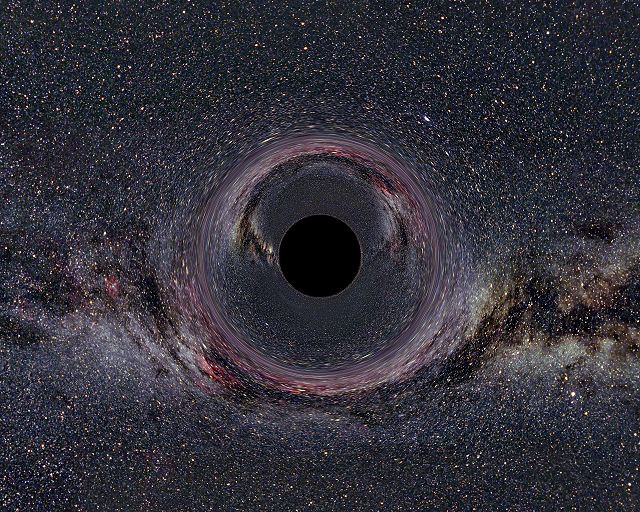

But one of the most interesting questions — and one that doesn’t seem to get much emphasis in the media — is, to whom exactly do we owe all this debt? We talk about “the debt” almost as if it were a kind of mythic Black Hole into which indentured humanity will have to pitch income forevermore, yet the debt must be owed to somebody. So who? Who are the blighters seated at the other end? Aliens?

To listen to the pols you’d think, indeed, we owe it all to the Chinese, who will therefore shortly become our lords and masters. Actually, that’s not really true; it’s just a convenient diversion. John Boehner, for example, recently attacked the debt-mongering (while ignoring that it’s mostly due to Bush tax cuts and Bush wars) by declaring that it was “immoral to rob our children’s future and make them beholden to China.” Truth is, this makes about as much sense as him pronouncing his name “Baner.” In Treasuries, for instance, our total debt to China is about $1.1 trillion. It’s not nothing, and there’s likely other debt than Treasuries, but in the whole $34 trillion scheme of things it’s clearly not the main problem.

The fact is, we owe most of this $34 trillion to our real lords and masters, viz., rich people. That is, John Boehner’s campaign-funders; hence the China diversion. It stands to reason, really. The debt built up because for decades our working stiff has been spending more than he makes. He was only able to do that because rich people were willing to lend him the money, which they did because (a) they have, literally, more money than they can spend; and (b) they needed to keep the economy humming along and so preserve the value of their investments. There’s a little bit more to it than that, which has partly to do with the magical ability of banks (N.B., owned by rich guys) to create money, but the essence is there: only people who don’t spend all their income, by definition, can lend money, so who the hell else would we be owing all that money to?

Now you can see why our economic system is prone to periodic crises. If rich guys take too much of the national income, year after year, the economy can’t sustain itself and eventually collapses. That’s maybe one reason why the countries with the highest income inequalities are often the poorest. In terms of the “Gini coefficient,” a measure of income inequality, the US ranks in the worst 30% in the world, right between Jamaica and Cameroon, and with greater inequality than such countries as Tunisia, Egypt and Libya.

In other words, income inequality is, in the long run, a recipe for economic disaster. And economic disaster isn’t good for anyone — not even rich guys. It might, for example, do the wealthy well to remember that, between 1928 and 1933, the number of millionaires in the US went from around 30,000 to around 5,000 (see Kevin Phillips, Wealth & Democracy). You can only suck so much blood before the victim dies, and then what are you going to do for food?

Clearly, what we need for our long-term economic health is a system that allocates income more equally. Theoretically, it would be possible to do this without taxation, by giving wage slaves a bigger share of the pie. But that would mean lowering executive pay and/or corporate profits, measures that probably won’t be accepted voluntarily. So we’re left with taxation. The fact is, it’s in the best interest of all Americans, including the high rollers, to raise the tax rate on the upper-income tiers. Taxing the rich isn’t just morally fair, it’s good for the economy. The more grounded and rational rich guys, like Warren Buffett and, recently, Bill Gross of Pimco, recognize this; but the current in Washington is clearly with the delusional fringe that thinks lowering taxes on the rich promotes growth. After all, worked pretty well so far; right, George?

The fact is, the economy will come back into balance at some point, either through defaults (which will result in rich guy creditors being no longer so rich), inflation (likewise) or a long and grinding repayment of the debt (rich guy stockholders no longer so rich). One way or the other, the rich-guy creditor-stockholder is going to take his drubbing. With little prospect of getting the rich-guy tax rate up near term, it looks like we’re going to have to do it the hard way. Forsooth!

Carl Hegelman (a pen name) is a corporate bond analyst and a connoisseur of leisure.

Image courtesy of the Gallery of Space Time Travel, via Wikimedia Commons.

A Temporary and Equitable Technocracy: SxSW's Hunter-Gatherers

by Joshua Heller

SXSW Interactive is the convergence of utopian techno-futurism and base primitivism. Men hold screens in front of their faces as they ride down escalators. These devices work the best that they ever have. Instead of Tweeting into a void, they’re communicating with people on the other side of the convention center. People use their location-based applications to tell friends which bars they’re at. Women that meet in passing can follow each others Tweets and reunite an hour later, better-informed. These technologies are working exactly the way their developers say they should. Human beings connect to one another.

But Austin during SXSW is not a good test-case for “real world application.” A restaurant in Austin can be “trending” with 225 people checking-in. Right now in Los Angeles, you’d be hard-pressed to find a restaurant within five miles that has two check-ins.

Here the online world is your real world. And it goes both ways: here you actually become friends with online comrades, away, for a moment, from the keyboard.

There are lots of people who have specific purposes for being in Austin. Representing a brand. Promoting an app. Finding investors for their start-up. These people use their corporate cultures to attend events strategically: “This specific Venture Capitalist will be at X party at Y time!” And they’ll keep a calendar to maximize their time, and hand out the most business cards.

But those visiting Austin without expense accounts or immediate deadlines wander SXSW with no real idea where to go. Since we have no structure telling us what we should do, and there are too many events going on (and my SXSW app doesn’t work), we travel by our basic human desires.

I have become a hunter gatherer, mostly using technology instead of eyeballs. “Where can I get free food? Where can I take a shit? Where can I become intoxicated at no charge?”

Once you’re guided by base desires, you don’t worry where you’re going, or the context of the place. You just follow your social media applications toward free hot dogs and unlimited “organic margaritas.”

* * *

I left the press suite to upgrade from cold breakfast tacos to beers and grilled cheese. A friend heard about “beer and brats” sponsored by Miller. We shared stories about being preyed on by the Hipster Grifter because of our immaculate beards. I went to a “trailer park” sponsored by Hewlett Packard for sour gummy worms. (Trailer park = “a pop-up experience that houses a community of creative influencers.”) I went to Cracked.com’s party for artisanal empanadas and cocktails. Many of these complimentary items were fertilized by the blood of Demand Media content farmers.

But you cannot have a conscience when you are looking to satisfy your needs. You should however at least wonder how long you can survive on booze and food that’s all the same color.

Previously: In Austin, Tweeting is Currency