France: This Country Sucks

France, the tourism capital of the world, is actually a xenophobic hellhole of white supremacists carrying baguettes. It is run by a tiny monster in platform shoes, and while France barely cracks the top 100 of most densely populated countries (ranking near Portugal and Albania), it leads the world in nationalist panic and manifestations of emotional scarcity.

Yesterday, a team of young enraged Catholics (with the support of the National Front!) busted into a gallery and destroyed Andres Serrano’s “Piss Christ” (how 80s) and another photograph, which depicted… a nun praying. (The vandalized photographs will remain in the exhibition, so people can think about what is wrong with people.) At the same time, France refused to accept a trainload of North African immigrants — with temporary visas — coming from Italy. (Unsurprisingly, they are mostly coming from Tunisia and Libya — and Italy is working with EU countries to send Tunisians back.) France eventually relented, because they had to. (But not without a bad attitude: “La France rejette les critiques italiennes,” says Le Monde today.) And who’s on France’s side? Mmm hmm: Germany.

What’s more? “The French spend more time eating and drinking, sleeping and shopping than any other nationality,” according to a new study — and are far less likely than other nationalities to have “performed an act of kindness in the past month.” Yes: the vast majority of French residents are more likely to have hissed at a woman in a burqa than to have given a tourist directions. When will we start bombing France?

See You At The Post Office

It was one of those chilly spring mornings specifically calibrated to make you want to cling to the covers and hit snooze seven times, but you couldn’t, could you, because you of course put off filing your taxes until the last minute and now most of your day will be spent standing in line with your fellow procrastinators while you wait to once again pay into the “certified mail” scam that the post office makes most of its money on at this time of the year. You’re going to be tired and irritable, but console yourself with the fact that you’re doing the right thing. Also, try and get as much sun as you can early; it’s going to get dark, and we won’t see the light again until Thursday.

The Week We Were Terrified of the Future

Four hours ago: Farewell, L. J. Davis.

One day ago: Liberty Tax Service: Your Huddled Masses Yearning To Be Franchisees.

Two days ago: Us. v Them: When the Liberal Media Met in Boston.

Three days ago: In Defense of Offensive Art.

Six months ago: Cherayla Davis, Amateur.

One year ago: Is It The Duty of Every Enlightened Female To Put Out?

Eighteen months ago: The Great Annual Change Bowl Cash-In!

Photo by Andrew Russeth.

Waking The Dead

“Many of his clients became friends, in particular Jeffrey Steiner, the billionaire head of the Fairchild Corporation, who had wandered into the original Pimlico Road shop one Saturday in 1988 and breezily dropped over £1 million. When staying at Steiner’s villa in the South of France, Hobbs claimed he was prevailed upon to supply a reefer to an elderly guest. The recipient collapsed after partaking and, it was assumed, had died. Panic ensued with Steiner insisting that the body be taken off his premises. But as Hobbs helped his host bundle the ‘cadaver’ into the boot of a car, it revived, to inquire, not unreasonably: ‘What the hell do you think you’re playing at?’”

— It probably says something about the life of dodgy antique dealer John Hobbs that this anecdote from his obituary strikes one of the more sedate notes in the piece.

The William S. Burroughs Doody Sculpture

“Sometimes you have to suffer for your art. Take, for example, a pair of artists who will are trying to extract DNA from the author William S. Burroughs’ preserved poop. They want to create a ‘mutant sculpture’ for their forthcoming exhibit, ‘Mutate or Die: a W.S. Burroughs Biotechnological Bestiary,’ and plan to fire DNA-covered gold dust from a device called a gene gun into a mélange of sperm, blood and more excrement. But will this effort even work?”

Bear Rescued From Awful Fate Of Being Stuck On The New Jersey Turnpike

This footage disappointingly cuts off before the actual moment of rescue, but “a black bear who was stuck in a tree near the New Jersey Turnpike has been removed… TV footage showed a firefighter and state officials fist-pump as they finished wrestling the tranquilized bruin into a fire department’s ladder truck.” What did you do today?

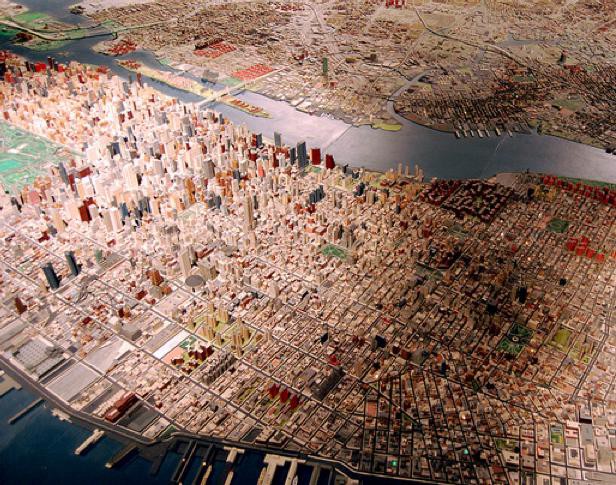

The Illuminated City

“The French are a people of fine sentiment, and they certainly carried the quality to a charming point of reflection in receiving light from candles made out of the bodies of their fathers.”

10 Best Los Angeles Thai Restaurant Website Soundtracks

by Eric Spiegelman

10. Chadaka

9. Tawanna

8. Pink Pepper

7. Poom Thai

6. Rama Thai

5. Rambutan

3. Chao Krung

3. Bangkok West (same as Chao Krung!)

2. Palms Thai

1. Tuk Tuk

Eric Spiegelman is a proprietor of Old Jews Telling Jokes.

The Day We Sorta Almost Did Away with the Government As We Know It

We came very close today to radically reshaping America, at least in the House, by means of the Democrats sitting out voting to try to give the right-ward arm of the Republicans the budget they wanted. That would have been fantastic! I’m very impressed by this stunt. In the end, it was fun enough that Republicans had to vote against the proposed right-wing budget just to keep it from passing. But worry not! Then the House passed a budget almost as ridiculous.

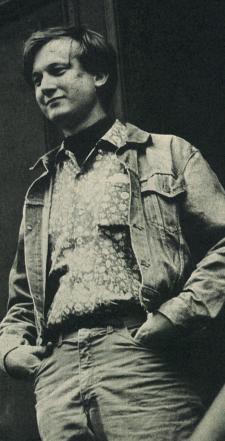

The Most Flagrantly Tactless First-Rate Brooklyn Novelist

by Evan Hughes

You know when you’re in a panel discussion in New York and the topic turns to gentrification, and the audience gets very quiet while everyone prays there won’t be some guy who stands up and says something excruciating? L. J. Davis was that guy.

Davis, a writer whose career was long enough that a lot of people forgot who he was for stretches along the way, died last week at 70. He wrote four novels in the ’60s and ’70s and, over a longer span, produced a substantial body of cranky and annoyingly accurate journalism. (A Harper’s article that essentially called the 1987 market crash won him a National Magazine Award.)

In 1965, when he was 24, Davis made the questionable decision to buy a decaying old house in Brooklyn, on Dean Street in Boerum Hill. It was the era of white flight, and he was fleeing in the wrong direction. Then he did something even more reckless. He saw what was beginning to happen in brownstone Brooklyn and mined it for laughs.

His third novel, A Meaningful Life (1971), a pitch-black comedy and a small masterpiece, starts out moving along nicely in the vein of Davis’s previous book, Cowboys Don’t Cry , in which the immigrant parents of the bungling, boozing protagonist gave him the all-American name Clark Kent in 1937, the year before Superman appeared and prematurely ruined his life. A Meaningful Life likewise appears to be a good old Schlemiel Novel, a cousin to Kingsley Amis’s Lucky Jim, Richard Russo’s Straight Man, Sam Lipsyte’s anything.

Early on, Lowell Lake, our hero pathetico, sets out to write a novel on a nocturnal schedule while living on the Upper West Side with his unpleasant wife. While she brings in an income and berates him, he becomes so unmanned and sickly that the newsstand guy wonders aloud if he has the strength to carry home the Sunday Times. Soon Lowell gives up the novel, citing its “overwhelming livid awfulness,” and gets a job at a plumbing-trade weekly (not one of the better ones). At this point he surveys his prospects:

It was surprisingly easy for him to imagine what the rest of life held in store for him, short of Negro rebellion or atomic war. It did not hold much, and he would go through it sort of standing around mutely in tense attitudes reminiscent of Montgomery Clift, not particularly liking what was happening to him but totally unable to think of a single thing to do about it.

We’re in good hands here, we think. Things will go wrong for this guy, but not so wrong as all that, and we’ll be chuckling all along. This is incorrect.

Lowell decides to take a look at a massive 19th-century mansion that’s been turned into a rotting boardinghouse in a “slummed up” Brooklyn neighborhood (it’s Clinton Hill). He’s become inspired by a new trend: “Creative young people were buying houses in the Brooklyn slums, integrating all-Negro blocks, and coming firmly to grips with poverty and municipal corruption. It was the stuff of life. It was what he was looking for.” This is the first straightforward expression of enthusiasm in the book, which is to say it’s the first sign of trouble.

Built for one family, the house is teeming with poor people when Lowell buys it. The shady real estate agent has told him the place will be “delivered vacant,” as they say. But Lowell ends up faced with the task of forcing out the black and Hispanic people who preceded him so he can fix up the place, giving rise to a highly charged microcosm of the whole story of Brooklyn’s gentrification.

On the one hand, the narrative that follows is a very funny cascade of ill fortune, with a mix of outright pratfalls and perceptive dark humor. Lowell at one point takes a walk to visit a fellow white gentrifier he’s met and comes upon a block “so hyperbolically poverty-stricken that it didn’t look real; it looked contrived, like a set for some kind of incredibly squalid version of Porgy and Bess.” A local drunk threatens him as he approaches his destination. When Lowell is turned away by the white man’s suspicious wife, the drunk “commented on his adventure with a joyless but outrageously energetic parody of uncontrollable mirth, evidently having decided that this would get Lowell’s goat more effectively than his previous display of unbridled hostility. This insight was correct.”

On another occasion a nasty-looking old white woman appears across the fence from Lowell’s new backyard and interrogates him oddly, lamenting the course of the neighborhood and Lowell’s idiocy in moving there. As he tries to escape the conversation, a half-naked, toothless black man shouts at him from the other side of his yard. “The old man was much older than the old woman, and it was obvious that he was also much crazier… Lowell glanced around at the other yards that were visible from where he stood, half expecting to see more old people proliferating in various degrees of madness and nudity, like some kind of ghastly, pale fungus.” The whole episode depresses him, especially when the neighbors’ remarks begins to make a poignant kind of sense. What to do? Lowell “got moodily drunk in a very total way, and silently failed to arrive at any conclusion about what was wrong with him.”

Amidst the comedy, Davis produces the most lacerating portrait of the folly and shame that gentrification brings with it everywhere it goes. A Meaningful Life closely tracks Lowell’s point of view, and as he grows to resent the way his impoverished neighbors are making life difficult, at times it becomes hard to tell the book apart from a racist novel. I hate to say that, and yet I think Davis would cheerfully agree. Like a comic actor with the crucial willingness to make himself look ridiculous, Davis sacrifices our good opinion for the sake of the art. He makes you think hard about whether this L. J. Davis guy is a bigot, and that means thinking hard about what bigotry is. (Those tempted to judge Davis’s true attitudes may be surprised to learn that he adopted two black daughters to grow up alongside his white children.)

If you’ve ever felt uneasy about the fact that in your once-diverse neighborhood you are helping to make the streets safe for Corcoran and quinoa, Davis exploits that feeling to the extreme. If you’ve been priced out of that neighborhood and you’re bitter about it, the same goes for you. It’s all a bit cruel, really.

Like Davis’s other novels, A Meaningful Life got great reviews and generally failed to find an audience. In 2009, Jonathan Lethem, a friend of Davis’s son on Dean Street growing up, and Edwin Frank, the editor of New York Review Books Classics, rescued the book from the dustbin with a new edition, introduced by Lethem. The novel has since sold more copies than it did the first time around. Which may be because gentrification was a fringe story 40 years ago, when Davis foresaw the whole mess we were headed for. In the decades since, I’m not sure anyone has topped the crackpot insight that his incredible tactlessness brought to bear.

Evan Hughes’s book, Literary Brooklyn, a work of literary biography and urban history, will be published in August by Henry Holt. He’s on twitter.