The Twilight of Carnegie Deli

The last mountains of pastrami will go out on New Year’s Eve

“You never know what’s going to happen here at the Carnegie Deli, particularly on New Year’s Eve.” Murray Trachtenberg, the restaurant’s longtime general manager, was teasing another night of gruff service and obscenely portioned smoked meats when he said this to the New York Times in 1991. But this year, after seventy-nine years, the Carnegie Deli will be serving its last sandwich on December 31st.

Carnegie Deli is a monument to relentless schtick and cultural nostalgia. It’s a Disneyland that was once real. You can feel the ghosts, the steady march of Judaism toward the American mainstream. Celebrity photographs line its walls, many questionable in their inclusion (The Fat Jew sits neatly behind the cash register between Rihanna and Kate Upton).

Like anything good in New York, it all starts with the line. I walked into a whisper-scream dispute between a couple from Wisconsin.

“I don’t want any of this,” the man said, running his finger down a takeout menu. “Why would I pay this much for a sandwich?”

Rich, a connoisseur of blintzes and the only self-professed local in line, brought two friends along. “I’ve been coming here since I was six. Fifty years.” I asked where he’ll go now that the deli is closing. “Nowhere,” he said. “This is the end. I mean, there’s Katz’s, but it’s not the same. Maybe, now that it’s closing, they’ll finally give me the recipe.”

“I have a friend who drives in from Central Jersey for the corned beef,” another woman said. “I can’t tell the difference.”

When Dani from Illinois heard an estimate for how long the wait would be, she blanched. “Forty-five minutes?” she said, making a face like someone just rang the doorbell to tell her that her son died in a war. “Isn’t there another option? My feet are so tired.”

Carnegie Deli is the last in a lineage of Midtown giants. After rent increases forced the Stage Deli — a longtime sparring partner just one block south on Seventh Avenue — to shutter its doors in 2012, Carnegie has monopolized the market for $30 sandwiches in the area. It represents the glitziest branch of New York delis, the culmination of what food critic John Mariani once called “American bounty in its most voluptuous and self-indulgent form.”

“The Carnegie Deli was the last link to it,” said David Sax, author of a wonderful ode to pastrami called Save The Deli. “Of course, it was more of a kind of schtick-ified version than it had been in the past when that was real. That neighborhood had changed, and it was still holding on to that feeling. The comedy writers, the great classic world of Woody Allen and vaudeville and Broadway, Mel Brooks and all that, had long since left for other parts of the city or Los Angeles.”

After an influx of Eastern European Jews immigrated to the Lower East Side of Manhattan in the late 1800s, delis established a deeper presence among the tenements. They evolved from German roots, hawking a combination of smoked meats, sausages, prepared meals, and pickled vegetables. The food — a cultural mishmash of Germanic, Southeastern European, and Russian cuisines — became commonplace, especially on holidays and special occasions when families would gather around the table to nosh on corned beef, brisket, and pastrami, always with pieces of caraway seed-dotted rye bread.

This scene, the warmth and comfort of family, is what some visitors to Carnegie Deli told me they wanted to experience, but the OG delis were not destination restaurants. They were hyperlocal, much closer to what we now know as bodegas. There were typically few seats, but the counters were overstuffed with pretty much any culinary item one could imagine, including mostly forgotten specialties like tongue and gribenes.

As decades passed, Jews became more entrenched in American life. They earned more money and were happy to spend it on the biggest sandwiches known to man. The mid-century sandwich said, “We’ve made it — now take half home with you and enjoy.” Midtown Manhattan became a cultural space for restaurants like the Carnegie Deli, which stayed open all night, had menus thick as Philip Roth novels, and, in Carnegie’s case, an owner who made sculptures out of chopped liver to commemorate famous wars.

The culinary legacy of Carnegie Deli starts and ends with the meat. Pastrami, real pastrami, comes from a time- and labor-intensive process. To make it the traditional way, a beef brisket is smothered in pink curing salt, a method that brings out its flavors and gives it color and texture. Spices like black peppercorn and coriander seed, blended according to closely-guarded recipes, are rubbed into the meat, which is then smoked for around two weeks. It is usually boiled to finish and then kept in steam trays before — hot, but not too hot — it’s carved and served.

Pastrami may be a lasting innovation of the Jewish-American deli, but the quality standards in its production have degraded over time. Companies like Boar’s Head manufacture a phosphate-injected version that is far easier (and cheaper) to mass produce. Subway is currently advertising a pastrami sandwich that tastes closer to synthetic roast beef.

“People won’t spend as much on a pastrami sandwich as they might on a steak, even though the actual cost to make those things are probably about the same,” said Noah Bernamoff, the founder and owner of Mile End, which is the center of a new-wave deli movement in New York. “The cost of a steak cut from the rib loin of a cow costs about the same amount of money as the end-cost of making pastrami from a lesser-expensive cut of meat like brisket. It’s the same end-cost, but we’re not allowed to serve it at steak prices because Boar’s Head exists in the market and pulls everything down.”

The gargantuan sandwiches pedaled by Carnegie and its ilk often include more than a pound of meat, yet cost less to produce than what nü-Jewish delis like Mile End and Harry & Ida’s are serving with eight ounces. (See also: Wexler’s in LA, Caplansky’s in Toronto, Kenny and Zuke’s in Portland, and many more.) It’s the age-old quantity versus quality debate, and as traditionalists like Carnegie cut their last slices, delis which use the best-possible ingredients and simplified, time-intensive recipes are succeeding with healthier meat crafted in smaller batches. “People come in and look at our sandwich and go, ‘What? This isn’t a deli sandwich,’” continued Bernamoff. “But no, it is a deli sandwich. You’re just so used to buying one that you eat now and you eat tomorrow.”

It is certainly better, but it’s not the same. For Jeff Parker, owner of Ben’s Best in Rego Park, tradition is tradition. What Carnegie put on the plate will be considered the classic version of what chefs like Bernamoff have updated for the 21st century. “If you want a Peter Luger steak, you go to Peter Luger,” Parker said. “That’s the one you want. If you want to go some place where they’re gonna go au poivre or put a bearnaise sauce on it, well, that’s another set of circumstances.”

Under a graveyard of forgotten sitcom actors, two couples in head-to-toe North Face were surrounded with enough food around them to last a week. I asked why they ordered four sandwiches when two would have been sufficient, especially with the blintzes and cheesecake gathering dust in front of them.

“We had no idea,” one of the wives said. When I pointed out if they shared, they’d be charged three dollars extra per person — the store’s flagrantly manipulative “sharing charge” — they thought I was lying. After their meal, the husbands stood to pat their server, Al, on the back and shake his hand. They also flagged down John, the general manager, to thank him.

I later asked John why they were closing; Marian Harper, a second-generation owner of the deli, owns the building. There’s no greedy landlord to blame, and the ever-present line down Seventh Avenue is proof of an (un)healthy demand for sandwiches named after Woody Allen. “For ten months, she wasn’t here, and she got a taste of what it’s like not being here all the time,” he said, directing me to their media relations department.

It’s an excuse that glosses over what makes the predicament of the Carnegie Deli so fascinating. That ten-month sabbatical was due to a forced shutdown after, in April 2015, ConEd discovered the restaurant was operating with an illegal gas hookup. There was no punishment beyond a retroactive $40,050 bill and a $2,600 fine to the Buildings Department. The year before, the deli entered a $2.65 million settlement with present and former waitstaff, who sued after being cheated out of wages over the previous decade. Around sixty employees, many of whom returned to the restaurant after it was shuttered for nearly a year, will now be out of work with its closure.

Judge Matthew Cooper of the Manhattan Supreme Court harped on the restaurant’s penchant for wage theft during widely publicized divorce proceedings between Harper and her business partner, Sandy Levine. In August 2015, he referred to Levine as a “shyster of smoked meat” and claimed the couple had made “millions of dollars on the backs of dishwashers and cleaners and pastrami slicers who make as much in a year as they’ve made in a day or two.” A major catalyst for the divorce was an affair between Levine and Penkae Siricharoen, a longtime server at the restaurant, who, while living above the deli in a rent-stabilized apartment, used stolen recipes to open an unsanctioned version of the Carnegie Deli in Thailand. In September 2015, Levine settled the divorce and a $10 million fraud suit for an undisclosed sum.

“It was an outlandish place,” said Sax. “It was packed. It was overpriced. It was kitschy. The portion sizes were idiotically large. Everything there seemed like a performance, and that’s what was great about it. I don’t think you can ever replicate that. It was the nature of where it was, who owned it, and how it evolved. People will say there are better tasting Jewish delis. There are more homey Jewish delis, but are there more fun Jewish delis that existed than the Carnegie Deli at its peak when it’s absolutely packed with people from around the world? I don’t know.”

“I think it’s a shame,” said Jay Parker. “It was a tremendous institution. Its passing diminishes the industry, in my estimation.”

“I don’t want to be negative,” said Bernamoff. “In Yiddish or Hebrew there’s a notion of lashon hara, the evil tongue, so I’m sensitive around using it with my deli brethren who, for better or worse, are dying.”

Carnegie Deli will continue to serve as a model of both golden-era New York (with its attitude and schmaltz) and Americana (with its altars to celebrity and portion size). In its first week back in business after the closure for siphoning illegal gas, one of the deli’s customers was Mayor Bill de Blasio. He posted a picture of his favorite sandwich with a single-word caption: “America.”

I Can't Publish My Interview With An Awful Man

Because we can’t give him the attention.

I met the awful man on a website. The website, while not without its problems, is not completely terrible (and it’s not the one you’re thinking of). Its problems boil down to the preoccupations of a specific community, and more than that, to the pathologies of an annoying, self-important subculture within that community. In said community, which still serves a basic function I value, the awful man is someone you’d be encouraged to ignore. That’s what everyone does, and that’s what I’d counsel as well, despite writing about him here in a way I hope will preclude any satisfaction whatsoever on his part: It’s clear that he loves to be written about.

The awful man does have an account on the website you’re thinking of, but you can tell he’s not crazy about it. That account exists so he can get people to look at the other one. So, come to think of it, I may have met the awful man on the website you were thinking of, and found his other account, about a year ago now. His grainy avatar is a white guy whose eyes are bright yellow from the camera flash. I have no idea if that’s really him, and in those moments when I begin to suspect that “he” is in fact some tortured algorithm, I must admit that it’s an ideal visual presence for his project: some ghastly relic of the old internet, a lost message board.

His project, which does arouse an unfortunate curiosity, is a creatively unhinged sort of harassment that takes on the cadence of schizophrenic poetry — the sort of rarefied abuse that, as a white man, I have the privilege of approaching with anthropological interest. I could analyze his rhetoric and look for clues to a true personality. I’d prod him until he presented differently. I had become a target, it’s true, but again, because of my position, I’ve never felt acutely threatened by trolls of any stripe. I engaged, I emailed, I questioned his strange behavior. And, of course, he was eager to talk, to unload even more of his apocalyptic language.

I could see even then that we weren’t getting anywhere, that what he said could never be corralled into anything like a legible profile or interview, however compellingly odd he was, and despite my misplaced attentions. Ethically, my first concern was his mental state, which I could not hope to ascertain. Then it became clear, as he heckled me for more questions, threatened to “shut down” the conversation, and bragged that he’d been written up in an Italian newspaper, that he was pushing for wider exposure, demanding further recognition. His normal schtick was secondary to this motive; I realized that our sort of exchange was exactly what he fed on.

He ramped up his impotent threats — there was nothing he could do to or take from me, yet a key to his madness lay in delusions of godly control that derived from his words — and I wondered what I’d hoped to accomplish by taking him seriously. I imagined there was a person to be explained, and found instead that he was nothing beyond his hatred, which often bizarrely coexisted alongside his manners. “Thanks,” he wrote back when I told him we’d reached the end of our on-the-record dialogue, “I enjoyed working with you.” Me, one of his chosen victims. It was maddening to see him veer toward self-awareness right before erupting again.

I can’t say I hadn’t been warned, either. When the awful man and I first publicly interacted, at least one colleague told me that my interviewee was precisely what he seemed, and not worth figuring out. Around the same time, one of my oldest friends had started to send me insane emails with the same aggressive, accusatory, literary bent, and refused to directly reply to anything I wrote back. Maybe I believed that, in talking to the awful man, I’d gain the insight I needed to help my friend, who appeared in the process of becoming an awful man himself. Was there anything to be gained, apart from a certain quietude, by casting both of them aside?

And even as the weeks and months went by, as the entire awful year separating me from the awful man unspooled its ribbon of horrors, I held to the notion that what we’d said to each other might form the basis of a coherent essay, a thing I could publish and be paid and praised for. I half-heartedly pitched it to a single editor, who confirmed what I’d known all along: that there was no value in it, no point in giving the awful man a platform, no excuse for proving his point. That was all I required from the universe, and afterward I deleted all relevant notes. It was over. At least I could congratulate myself for failing to carry out his demented prophecy.

For all I know, the awful man is obsessed enough to have followed my work since I first took his bait. I know that I check in on him now and then. He is still so mystic and appalling, so dogged in his purpose, and, at times, to a morbid sensibility like mine, unintentionally funny. Does it matter to him that I stopped listening? Or is he content to go on shrieking into the void until another idle commentator decides there is pathos below his curdled surface? We have to at some point admit that we can’t create meaning for people like him. Surely there are failures and fears at the roots of his sad ritual — I’m just mildly ashamed, after all, that I tried to dig them up.

You Are In An Abusive Relationship With The Internet

The Internet is bad, everyone knows it, and we’re just going to keep doing it to ourselves.

“Sharing,” once purportedly the ultimate thing to do online, has become unwise now that we have the whole internet to wield against one another. The safest tack is to serve as little personal information, or as few identifying details to public platforms as possible.… Somehow things have reversed, and now the internet is a place for your buttoned-up self, with the untidy entrails of your real life shoved under the bed, lurking outside the edges of your normal-looking Instagrams. The internet has transformed from a place you could safely hide certain feelings and appetites into a place where you can get in trouble for them.

No one needs to be sold on how bad the Internet is now, and “Why this was the year the Internet became the worst” is a genre that will never lack for content so long as we have an Internet to put it on. (“Remember when the Internet used to be good” has already established itself as the same reliable provider of ways to express just how terrible things are these days.) That said, Leigh Alexander’s crack at explaining why even thinking about being online makes us want to die is worth your time if you need a reminder that you are not alone in so feeling.

Donald Trump And ️NBCUniversal

It’s Comcast all the way down.

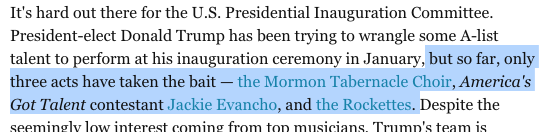

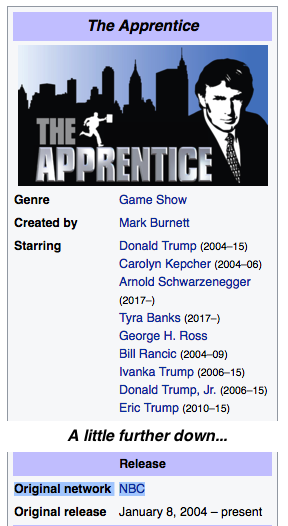

This morning I clicked on an article and within a few sentences I was going, “Hmm.” Let’s see if you notice the same pattern:

Hmm.

Hmm.

Hmm.

Hmm.

Hmm, right? Hmm.

> Your best of 2016

From Everything Changes, the Awl’s newsletter. Subscribe here.

Here is my Best of 2016. What’s yours?

- The end of a dock on a lake in the non-night of Finnish summer.

- A dog my boyfriend and I adopted in October. Based on a blurry Instagram video, we ended up applying for a funny-looking waggle-butted mutt, a badly underfed 15 pounds upon rescue in Tennessee (from a dog hoarder, we think). We’ve had her two months and are already at the point where we say “Bless you” every time she sneezes. She sneezes quite a lot. (A friend said: I’m so glad you got a dog, just in time.)

- A moment on election night, before everything that happened happened, when my boyfriend and I were rushing from upper Manhattan to get to friends in Red Hook before the results were called, when we stopped to buy liquor and were considering the choices for champagne when my boyfriend said “Fuck it, it’s a big night,” and grabbed the most atrociously expensive bottle the shop had to offer. I hold on to that feeling of the hours before, when we thought the world was better than it was. The bottle of champagne is still in our refrigerator. Every time I get cream for my coffee, I remember that belief in better, and the fact that we will only be able to usher in history once.

- A goddaughter I acquired a few weeks after the election. Her parents put tiny hats on her. What a world that contain this little girl and everything else, all at once.

The Sixteen, "Adam Lay Ybounden"

Christmas hasn’t come yet but you’ve already done it wrong.

You made it. Tomorrow’s the Eve, Sunday’s the day and then Christmas is over. Are you already starting to feel like you didn’t do it right this year? Like you were too or distracted or depressed or otherwise engaged to really embrace everything about the season that made you happy in the past? Well, that is called being an adult. Christmas is always a disappointment after about the age of 11, and each year you get further away from it the greater the disappointment is. You still have two days to chase that childhood feeling of comfort and love but it’s not going to happen because life’s not sweet that way. Every summer there is a moment where you are walking around in the sunshine and heat and you are suddenly filled with a powerful nostalgia for Christmas, and every time the holiday comes back around you fuck it up again. That’s you, but that’s also part of being human. The good news might be found in the original lyrics of the holiday standard “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas,” which included the line “It may be your last.” Has that ever been more true? It has not. Anyway, here’s something lovely from The Sixteen. Enjoy, and happy holidays.

New York City, December 21, 2016

★★★ The daylight got off to a good start, under the circumstances, then faltered. By afternoon, the most the defeated sun could do was to add an incandescent-bulb tint to the flat gray that had taken over. The dirty ice in the gutters was melting a little around the edges but was still there. Soon enough the light was the cobalt of evening, and soon enough even that gave way to the full, swift-conquering night.

Languages, "Sleep Stream (Ewan Pearson Remix -- Instrumental)"

Going up?

I have been listening to this one over and over during the course of the week, trying to figure out what is so captivating about it. My best guess is the sense of upward motion: You feel as if it is very slowly ascending the whole time. If that makes sense. I mean, it does to me, you are probably like, “What are you talking about, you idiot?” Anyway, listen yourself and let me know if you can. Enjoy.

Not In My Nature

What’s worse than reading about trees?

“A friend asked a climate scientist what we should really do to prepare for climate change, and the scientist responded, ‘Teach your children to fight with knives.’”

Can we talk about how boring nature writing is? I mean, most writing is boring to a certain extent, but sweet mother of Christ, nine paragraphs on the way the light plays on the lake after a summer storm and I am ready to vote Republican. Nature writing is so boring, oh my God. But perhaps you disagree. Well, this guy makes a better case against it than I do. Have a look.

Tickling Rats For Science

What does a laughing rat sound like?

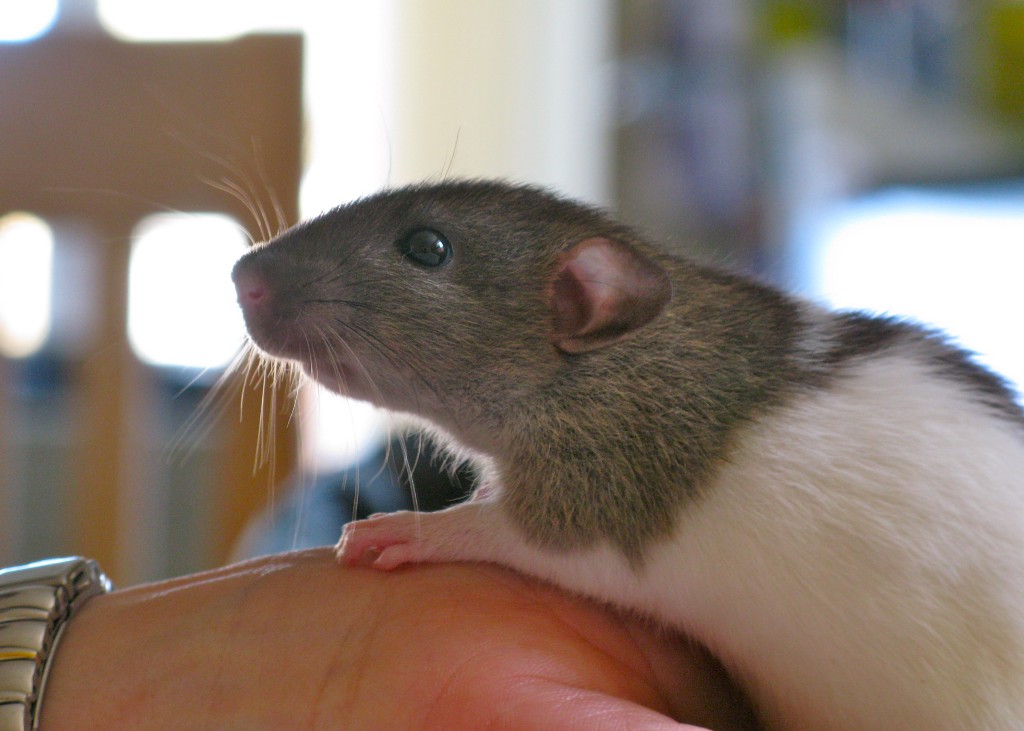

If you’re thinking of endearing animals, rats might not be your first pick, but when an experiment’s premise is “We tickled rats to see if they like it,” it’s hard to deny the novelty. This fall, a study published in the journal Science announced that neuroscience researchers had confirmed rats generally enjoy being tickled. During a tickle, they raise their voices up to the 50 kilohertz pitch range, which is the same high tone of voice they use when they’re greeting each other or are in a good mood (it’s nearly 30 kilohertz higher than the tone they use when they’re annoyed, and imperceptible to human ears). This, the scientists concluded, is essentially a laugh. Think of how a human’s voice might go higher if they’re talking to a dog or a baby—it’s involuntary, and is usually intended to signal, “This interaction is pleasant for me.” The same seems to be true for a rat.

When you stop tickling them, they follow your hand until you start again, and if they’re really hyped up off a tickle, they’ll even jump for joy. National Geographic has a video that shows what I mean (start at 1:00 for the sounds; Ed. note: normally this would be embedded but National Geographic wants your ):

Using these findings as a foundation, a team at Switzerland’s University of Bern has set out to see if they can identify positive emotions in rats, and it seems like the answer is “Yes.” By essentially: 1) observing a rat pre-tickle, 2) tickling the rat, and then 3) observing her post-tickle, researchers were able to track different physical cues that might tip us off to a rat’s mood.

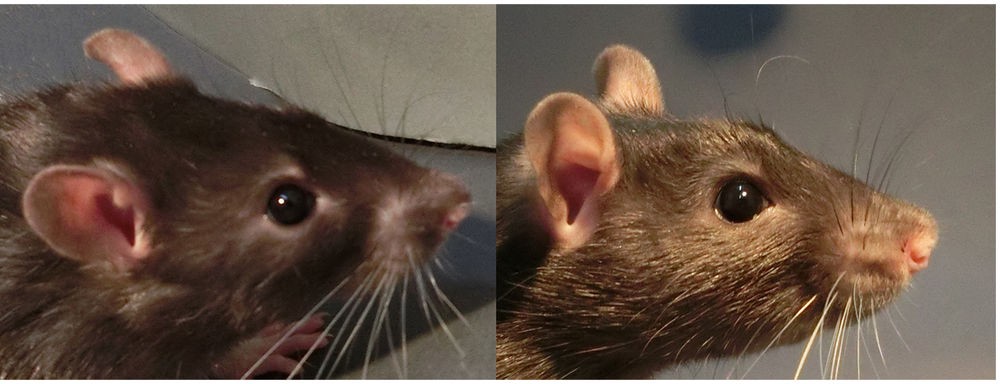

The biggest clue is the ears. When a rat’s ears are pink and held at a wide angle (out to the sides, listening to her general surroundings), she’s in a good mood. If her ears are paler and up at attention (pointed at one specific source), she’s probably more tense.

It’s pretty straightforward. The same way you can look at someone from across the room and get the gist of what’s going on with them from their facial expressions and body language, rats are unknowingly signaling their moods to us too.

So the next time you see one of these guys on the subway platform or darting past you on the sidewalk, keep your eyes peeled for their ear position—they might be just as grossed out by you. Don’t tickle them, though.