New York City, December 27, 2016

★★ A loudly splashing and sloshing night led into a morning of floating mist, so light there were dry patches along the line where the buildings met the sidewalk. Even so the dampness was like being toweled off in reverse, gradually but insistently prickling into the coat and the face. Two stops downtown, though, and the mist was gone. From inside MoMA, where the white walls admitted any sort of view, it seemed at first as if the gloom was enduring. That was, however, simply the shadow pit of the architecture and the neighborhood. With effort, intimations of light could be found, high up and far away. On Sixth Avenue, outside the dim canyon, the sun was abruptly blinding; the flags, even the hopeless state flag, swung like colored lanterns. Rays of glare and long shadows knifed out from the mobs at the crosswalks in baffling profusion and intensity. The temperature was so mild it made no sense.

Jane The Canine

In my other life, I am a corgi.

Do you know who else was a corgi? Susan, Queen Elizabeth II’s first corgi. Ah yes, Susan: the only princess our royal highness ever deigned to bow to. Unlike most humans, Susan made an impact. Some of the Queen’s current corgis are descendants of Susan. Long live Susan etc.

When you’re a corgi, the world is your oyster, and you are inversely everyone else’s world. Taking a lead from Liz, we let our corgis romp around during visits from international dignitaries, and we have our henchmen carry these corgis up and down the stairs of our private planes because corgi legs are just too dainty. One can really do no wrong as a corgi. I’m so upset that I got photobombed by a corgi, said no one ever. Even one’s horrendously foul farts are perceived as adorable, when one is a corgi. “I’m sawwy, I fawted,” you say (as a corgi), and everyone laughs. It’s simply just too fucking cute.

These are some things I know about corgis: they’re food aggressive with a tendency toward the chunky, they shed a lot, they’re terribly gassy, they’re menaces around the house, they’re at once playful and stubborn. Sometimes I actually wonder if maybe I already am a corgi haha.

Look, I follow about 13 private corgi Facebook groups (“Corgi Nation Corgi Strong Corgi On,” “Disapproving Corgis,” “Naughty Corgi Confessions,” a support group for owners of overweight corgis named “Corgi Fit,” among others) and have an Instagram account (@corgiandbess) solely for corgi content where I currently follow 610 corgi accounts. So yes I know all about corgis. Once, I walked/carried a corgi named Giles 3 miles around a lake and would go so far as to call it a religious experience.

At grad school — where I bring about 100000% less joy to the world than a corgi — I actually think a lot about subjunctivities. Henry James’s novels are all about “what would it look like if this character had lived life differently?” The horror genre is about plots gone awry at basically every turn. I’m still obsessed with Kate Atkinson’s Life After Life (2013) which follows what is now an almost established fictional tradition of taking Hitler as its site of counterfactual fantasy. The morning of my qualifying exams, the first thing I did upon waking was read the Wikipedia article for Eva Braun. The impossible is possible, history is a nightmare from which I am trying to wake, the past is never past, and I think many of us would love some kind of a do-over on this year, if not this life. For me, personally, it’s to start over as a specific purebred dog. You know who doesn’t see race? Corgis.

Jane Hu is a writer and grad student living in Oakland.

In My Other Life, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2016.

This Is Where I Live Now

In my other life, I was a musician.

My apologies, fellow traveller, I can only guess how I must look to you. The high-pitched trill in my ears is louder than the jet engine that carries us from John Elway to Pittsburgh International, and there’s a turbulence between them that makes the overhead lights too bright for my eyes to bear. Post-concussion on an airplane is vertigo on top of delirium; the opposite of the bends. Like plunging down in a submarine to find a lake on the floor of the ocean. Call it compression sickness.

When I left home the day after Thanksgiving, I knew exactly what I was (musician), and exactly where I was headed (out west, in a van) and now here we are, going east in an airplane, you with wrapped gifts poking out of your carry-on, me with a headful of compasses pointing to all points. I can only guess how I must look to you.

I’ve been living out of this luggage for nearly a month and when I get home I will continue to live out of it for another week before it occurs to me to unpack. I will spend the next months trying to regain the vigor and enthusiasm for what has always been my passion, but I will find it gone. It died on the side of a frozen Wyoming highway in an upside-down van. I lived.

Kicking off a tour in your own town, surrounded by your own friends, is stacking the deck in your own favor. You fill the coffer, you play the songs they all know and you leave feeling like you’ve triumphed before you’ve even begun. See ya in a month! You hit the road, Bob Seger on full blast (hello, Cleveland!), but you’re barely across the Ohio line before you realize the headlights have shut off and the dashboard is flickering. hello, rural zanesville.

And so touring truly begins. You book a Motel 6 in the middle of nowhere and let your label and manager know that your van is dead (in a few weeks you’ll have a whole different metric for what is a dead van), and you sit in that grody motel, worrying about bedbugs and getting under each other’s skin. Before management can secure a replacement van, you lose a band member. This failure to begin is too much for his fragile psyche. Can’t blame you, friend, best of luck.

You’re off again in your shiny new(ish) van, maybe now a little too weary for the Seger, but happy to be putting a little more distance between yourself and home, nonetheless. The idle days have been costly and you need to log some serious driving hours to try and make up for it. You will spend the rest of the tour trying to shake this nagging feeling of a deficit of time, money, sleep. You won’t be able to.

Through Kentucky, Tennessee and Arkansas you drive, unload equipment, set up equipment, play for a bit, tear down, reload and repeat. And then you’re in Texas, where there are actual guys who look like cartoon Texas guys and the drives are so long and the terrain so barren you begin to wonder if you died and woke up in a Cormac McCarthy novel. Austin is cool, but all anyone there can talk about is how much better it was five, ten or fifteen years ago, so why have I bothered coming, and better yet, why do you still live here? San Antonio is a neon stripmall with the name of a city. In El Paso, you stand outside the venue, looking at The Border just a few feet away. The sound guy says the kidnappings have gone way down since El Chapo was arrested. Where were you when you heard Scott Weiland died?

Driving through the Arizona desert while the sun rises and your bandmates sleep in the back is the best part of the trip, until you cross the dunes into California. You make your way up the coast, stopping in all the important cities, and yeah, yeah, you play some shows, but it might be the most beautiful place on Earth. Scratch Fresno though, it’s populated entirely by ghost-pallored shopkeepers without social skills. By the time you get to the top you feel like a Red Hot Chili Peppers song become self-aware. The saltwater and sand are still in your teeth and in your bag through Portland and Seattle, but any uplift you get from the warm, coastal leg will be short-lived. It is December, after all, and Welcome to Montana.

When I signed on for this trip and saw the schedule and routing, it definitely wasn’t my first thought, and maybe it wasn’t my second or third, but it didn’t take long for it to dawn on me where we’d be going and what time of year it would be. Turns out no amount of pre-worrying could have made me any better prepared for the three days we spent driving through Montana and Wyoming in four feet of snow. I killed most of it supine on the third-row bench, soothing music blaring in my headphones, trying not to barf with fear. Every time I stuck my head up for a look, it was black as night regardless of time of day and there was all manner of vehicle littering either side of the highway in various states of crashed. I lay on that seat convinced that this van was my future tomb, the only uncertainty being where it would come to rest, wishing for a road closure and I’ll be damned if it didn’t happen in Casper, Wyoming. They have these big gates out there with ‘Do Not Enter’ signs on them that they can just throw across the roads when conditions get deadly enough.

I breathed my first sigh of relief in days when the van was in park in another motel lot. I fell asleep to the sound of a Republican primary debate featuring Donald Trump, thinking, Well, it can’t get any worse. When I woke up the next morning, the road was reopened.

Minutes later I was settling into the third row, safe in the assumption that the good people of The Wyoming Road Commission or whatever had my best interest at heart — surely they wouldn’t allow us to drive on a completely unsafe sheet of ice — when the back end kicked out. We did a near-perfect triple axel across both lanes of I-25, but failed to stick the landing. Stumbling around outside the upside down van in shin-deep snow, trying to pack roadside debris back into my bag, a cigarette like an arthritic finger in my hand too shaky to get it to my lips, the thought first occurred to me: This is no way to live. The sirens in the distance seemed the more pressing concern, but it wouldn’t go away.

Flying home now, the uncertainty comes to a crescendo louder than any siren or engine, but I’m not yet ready to hear it, the Monday-morning knell to this fifteen year long Lost Weekend. I’m trying to pen an exultant ending to a narrative that would only be a lie to myself. It would go something like this, and it would be total bullshit: “…As the wheels touched down in Pittsburgh, despite the tremor in my gut and the disorder in my thoughts, I couldn’t wait to take off again for the next one, because this is the life that I choose.”

John Dziuban is no longer a musician.

In My Other Life, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2016.

Adventure Man

In my other life, I was him.

It was in India, in Delhi, that I first saw Adventure Man in real life. Of course I’d imagined him and seen him in movies and read about him in books for years and years before that afternoon. Or was it morning? The time of day does not really matter and it was long enough ago (a decade? more than a decade!) that I remember it being bright and hot, hazy and noisy which, ha, take your pick: it was bright/hot/hazy/noisy almost every day I lived in Delhi except for when the fog-slash-pollution stuck low to the ground.

I was working there, sort of. I was an intern at India Today but they’d never had an intern for more than a few weeks. I was there for months and months and they didn’t quite know what to do with me. That afternoon (or whenever) I was meeting a classmate, my friend Dan, who was also an intern but not at India Today. India Express? Let’s go with that. Mostly what’s important was that we were two white guys in our young twenties semi-working in a semi-exotic city (to us), far from our midwest college and feeling kind of cool about it. Or, I was feeling kind of cool about it. Dan, it was hard to know. Then we saw Adventure Man.

You know Adventure Man because you know Indiana Jones. I mean not personally but you can imagine that look and expand it outward into an archetype and that is, more or less, what I’m talking about. That’s what Adventure Man looks like. A ruggedly handsome guy on the early end of middle age who appears entirely at ease in a land that is not his own. He is a traveler. Or, no: He is the traveler. Also he is wearing a hat that looks amazing on him, a hat that would look very silly on almost anyone else.

Adventure Man was walking toward me. I was staring at Adventure Man and, as we got closer, I saw that Adventure Man was staring back at me. Then Adventure Man nodded and touched the front of his hat as he passed me by. (I don’t think it was a fedora. It wasn’t the full Indy. Let’s say it was a Panama hat and he was in linen, a linen suit that wasn’t white, because that’d be too on the nose and sort of villainous.) In the moment, I wasn’t staring at Adventure Man because he was Adventure Man, but because he looked like me. He looked, like, eerily like me. Like I was seeing some vision of the future appear before me. A premonition. Maybe a goal, maybe a warning. Maybe that’s why he was staring back. What the hell was up with that nod?

“That was super weird,” Dan said. “That dude looked just like you.” I didn’t say anything. Several moments passed. The silence was prolonged enough that Dan eventually added something like, “I feel like I wasn’t suppose to see that,” and apologized for being there. Maybe you’re wondering how I know Dan said these things but can’t recall the time of day I saw Adventure Man. Well, memory is like that, and also I was at that point in my life keeping a pretty decent journal that included the entry: “Dan sees future self near Jantar Mantar. I see future self? Dan says: That was super weird. Then apologizes for being there.”

Needless to say Adventure Man burrowed into my concept of me and I embraced him wholeheartedly. Entire journal entries were all about following in this fella’s footsteps. I didn’t call him Adventure Man back then, though. But boy did I aim to be him.

Several months later I was traveling alone through northern India, in the foothills of the Himalayas and even into the real hills. For a week or so I backpacked outside of Dharamsala, longtime home to the Dalai Lama and many other exiled Tibetans. I was a traveler. I was the traveler. I was living as Adventure Man had showed me I was supposed to live.

One day I hiked to a misty mountaintop. Through the fog a huge griffon vulture glided very close to me, then circled back and came even closer, so close I fell flat to the ground to avoid it getting any nearer. That night it rained, and I slept in a little teahouse on the mountain. When I walked back into town at dawn through the drizzle I came upon a busload of German tourists who had an appointment with His Holiness. I followed them and sat in the back. The whole day I felt, somehow, unseen. Like I could go anywhere, experience everything, a stone skipping over a perfect reflective pond, hardly creating a ripple. I spoke almost no words to anyone that day. It was my twenty-second birthday. I’d never felt more free.

A year later, I was working for a magazine that had as its title the word Adventure. Yes, I was behind a desk most days, but still I was striving toward the image Adventure Man had nodded my way. I suppose you already know how this ends because the narrative arch of a young man living freely and adventurously then being, somehow, tamed or domesticated as he ages is a very, very cliched one. An entire genre of mostly mediocre books has guys like me reaching early middle age and then longing for escape. So they go in search of some explorer or lost city or whatever, and wow what do you know in the process they find themselves!?

Adventure Man looked like me and I wanted, for a long time, to be him and then all the usual things happened: I fell in love and got married and stuck around, saw people I love have kids of their own, saw relatives and friends — more people I love — die. Only all of those things except the first one happened over the past six months, a period that has contained the most joy and sorrow I’ve ever known in one ridiculously short period.

A few weeks ago, wanting to escape a little bit, I read a big science fiction novel about a group of humans traveling to a distant planet with the goal of settling it. The crew had been aboard their ship for generations, about 170 years from Earth. When they get to where they are supposed to be, it’s increasingly clear that it is not a place where they can make a life. Not, in other words, a home. So they try something dangerous and crazy: they decide to go back to a place that they’ve never known, back where they came from.

Settle is a very odd verb. Settlers are people who strike out into lands with the plan of making a life there, embracing something essentially insecure and unknown; but you can also settle down, into a life that insures security. To settle is be both risky and not risky at all, but the older I get the more I think the former is the truer sense of the word. To be present, a part of a place, to build a home and a life around that, to be there to see things that are joyful, yes, but also hard and very sad; to do all this maybe even with someone else, bundling up your life with theirs, this is far more adventurous than I once thought. This is to me right now the most adventurous thing imaginable.

Ryan Bradley is a writer in Los Angeles.

In My Other Life, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2016.

The Almost-Life Of Lindsay Rocketship

In my other life, I was extremely punk.

Sometime in 2001, I first read the (excellent) book Please Kill Me: The Unauthorized Oral History of Punk by Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain. From the book, I learned that all the punk musicians and hangers-on changed their given names to punk names — Johnny Thunders, Richard Hell, etc. The book was all I could talk about for weeks, which was easy because all my friends had read it too. It captured my imagination like no other work of non-fiction had.

As much as I loved the book, or the parts of the book that weren’t about the things Iggy Pop did to groupies in bed, I actually didn’t even…like…punk…music? I mean, I understood it more as a lifestyle aesthetic and a necessary step on the way to post punk than anything I wanted to put in my Discman. But I definitely thought of myself as “punk rock,” because just the year before I had dropped out of college in Florida and packed all my stuff in my Honda Civic hatchback and moved to New York basically on a whim and without knowing anybody or, crucially, bringing any money with me (I think I brought about $250.) Not only did I not have parental support, I had full parental hostility. Prior to reading Please Kill Me, I thought of myself as having moved to New York “the Madonna way,” but after, I knew I was punk.

Another way I related to punk rock was definitely the squalor. After couch surfing for a few months with friends of friends of my hometown crew and sleeping in that hatchback for a number of nights that seems to grow with every passing year, I had secured the walk-through bedroom in a railroad apartment on Union Avenue in Williamsburg, in a small slumlord-owned building without a lock on the front door, a bathroom ceiling that collapsed on a regular schedule and usually no heat or hot water. My half of the rent was $400, which I cobbled together with a mix of odd jobs: temping, personally assisting the wife of my favorite author ever, and, in winter, most lucratively, working as the coat check girl at Fez. I got one of those Social Security letters a few weeks ago and it says I made just over $2000 on the books in 2002.

Not only did I have appropriate punk levels of squalor at home (my roommate and I tried to make the place homey — for example, I painted my bedroom blood red and scrawled “WRITE YOUR WAY OUT OF HERE” on the wall above my desk along with the words “FREEDOM” and “SECURITY” with “SECURITY” crossed out), but I was also in a Chinatown bus relationship with a guy in Boston I’d been off and on with since high school, and he lived in a big house in Allston with 6 or so roommates and whomever those roommates were fucking at the time. It was the kind of place that always smelled like awful Boston pizza and where some different random dude could be found sleeping on the couch every weekend morning. I think it was condemned after they moved out: that’s how punk rock it was!

It was also punk rock because this dude (with whom I was in a kind of farcical, never actually verbalized, wide-open relationship) was the lead singer in a band that played out a lot and was part of the early-aughts Boston music scene (think makeoutclub, if you’re old enough to remember makeoutclub). They weren’t a punk band at all — too much keyboard and emotion — but at least they came by the lifestyle honestly.

One day during one of my Boston weekends, I announced to the gang that I wanted to legally change my last name to “Rocketship.” It would be my punk name, I said. Everyone nodded: it was unanimously agreed upon. Why “Rocketship,” you ask? Because that’s what the little girl I babysat for in college called me, so of course.

In my “Lindsay Rocketship” fantasy, this name change would be my version of Ulysses lashing himself to the mast of the boat, lest the siren calls of security, like a job with health insurance (which I’d taken to calling contemptuously, a “straight job,”), or a checking account, lure me into the typical unhappy American consumer lifestyle. “Lindsay Rocketship” would be like a front-of-the-neck tattoo reading “I’m ridiculous!” that would help me avoid distractions in my quest to — what, exactly? I didn’t know. Technically I’d moved to New York “to start a ‘zine” (LOL) but I didn’t want to be a musician or a performer or create any kind of art (except possibly performance art — I had recently been talked out of opening a post-9/11 “Hugging Booth” in Times Square), I just wanted to be the very most ME I could possibly be, a goal I worked toward tirelessly on a terrible Diaryland blog that is password protected for all eternity.

I didn’t change my last name to “Rocketship,” because I looked up the process online and found out that it costs money. But I kept it as a little goal in the back of my head, sure. And really, the most important thing with goals like this is just to talk about them all the time.

I never did have to WRITE MY WAY OUT OF the apartment on Union Avenue, because in the early morning hours of January 1, 2004, my roommate called me at the hotel in Boston where I was sleeping on the floor after a massive rager to tell me that it had burned down. Not down as in “to the ground,” just that our specific apartment had had an unexplained fire and was unlivable. I got on the Fung Wah bus for what would turn out to be the last time and went back to survey the fire and water damage: I’d lost almost everything, except, thankfully, sentimental stuff like my precious diaries and poetry and photo albums and shit, and what I hadn’t lost I had no way of moving. The Red Cross gave me a $150 gift certificate to Sears and my parents offered me the same one-way ticket home they always had and no more, but my friends came through. One who lived nearby let me store my computer at her place and then lent me her unlimited metrocard so I could move everything I could in big black plastic bags to the apartment of another friend in Manhattan who let me stay with him for a month (the hatchback having long been given away to a younger brother, with its glove compartment stuffed full of parking tickets). Another friend found me a cheap sublet. With my newfound forced life-assessment, I quickly dumped the Boston dude for good, and within a couple of months, I took a “straight job” — at Viacom, no less! The least punk rock place ever (though points for it being at Comedy Central and not MTV.)

Over the thousand years since all that, I’ve had plenty of acquaintances and friends who changed their names — usually because their given names were too common to be practical as writers, or to give themselves a middle name that made them feel strong (the tattoo analogy isn’t so far off), or changed their last names to their middle names after a divorce in a kind of re-brand. And it’s cool. Because it’s never to the level of “Lindsay Rocketship.”

There’s a reason movies and TV have that cliché of a character reaching a spiritual crossroads by “burning it all to the ground,” I just did it literally. After losing my worldly possessions (except, of course, my “papers”), I was finally ready to sprinkle some security on my freedom. Lindsay Rocketship will never be, though I do think of her every time I find myself doing something like “forgetting” to pay my quarterly estimated taxes, going to a house party with more than 12 attendees, or deciding to forgo the dental insurance. We all live our punk truth in our own ways.

Lindsay Robertson is a freelance editor (which is very punk) and is on Twitter.

In My Other Life, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2016.

New York City, December 26, 2016

★ The drizzle beaded on the cars till it trickled down them. It beaded on the trash bags till it trickled down them too. It floated in the headlights of the tractor trailer blocking the crosswalk. The day was not cold, not warm, nothing but gray and damp. Dogs circled things indifferently but not so indifferently that they would let the humans at the other end of the leashes keep walking.

Eggheads And Mopheads

What’s going on in Leonard Cohen’s secret life?

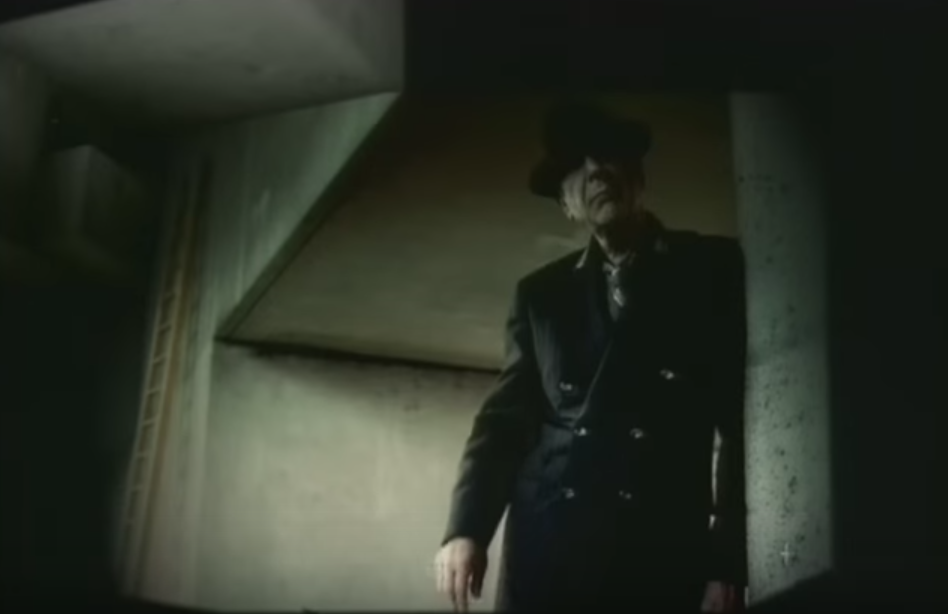

Leonard Cohen has no business being the most confusing part of the music video for “In My Secret Life,” but here we are.

The song itself is okay. It’s a Leonard Cohen song from 2001 about the past and a former love, but it’s not even the best Leonard Cohen song about the past and a former love. It charted at #2 in Poland.

The video, on the other hand, rules.

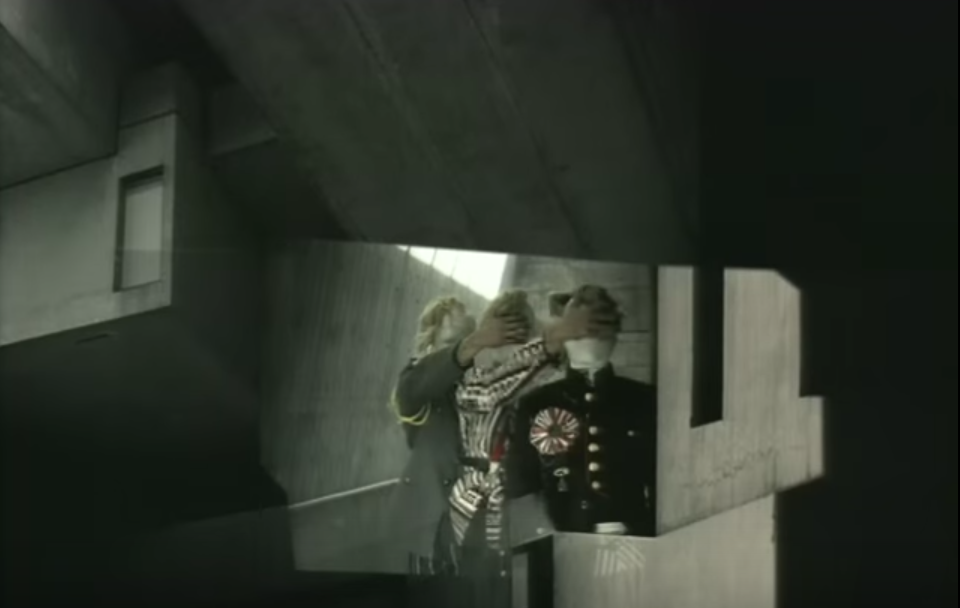

Against the backdrop of Habitat 67, a modular Montréal housing development, Cohen appears in a black suit, sunglasses, and fedora. He steps out of a shiny silver car and just sort of hangs out.

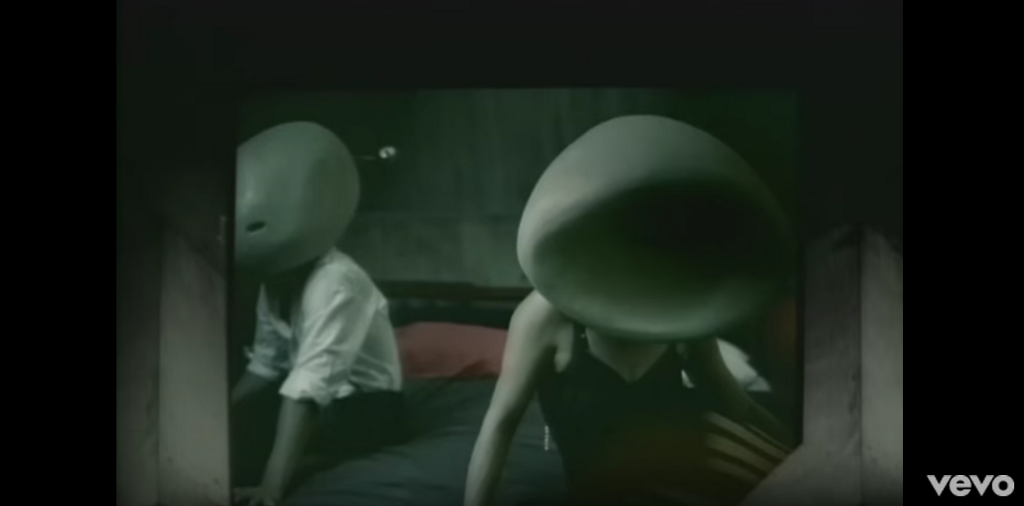

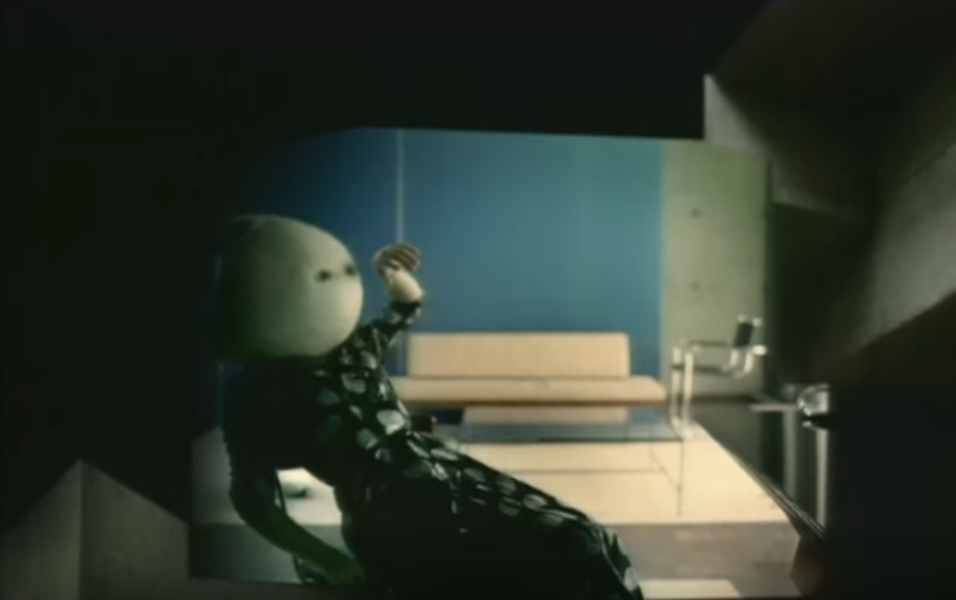

After Cohen died last month, I started watching the video a lot, mostly out of boredom and an unthinking interest in the humanoid figures who are the other stars of the video. Most of them have heads that look like ceramic hardboiled eggs with eyes and/or a mouth, some of them are concave. They act out little loops of everyday activity: breakfast with family, reading a (pulsating, red) newspaper, making out, fainting on a couch, being sad.

There are also the mop-headed people, who seem to really just love having fun.

Here are a couple of them on a tandem exercise bike:

As I clocked more and more visits to LeonardCohenVEVO, though, the most confusing person in the video was Leonard Cohen. Because this I can understand:

You’ve gotta eat, sometimes in class.

I can also understand this:

But why is Cohen hanging out in this stairwell?

Or reading in the middle of this courtyard?

Do you even live here, Leonard? Why are you staring at these egg people? Why are you so calm?

It’s the calm that gets me. Leonard Cohen, or at least his public persona, was calm in a way that endears him to many American dads of a certain age, and also to me, two sets of people that are preternaturally not calm. It’s not a calm anyone should emulate, because with few exceptions, the dads who emulate Cohen (they’re almost always dads), rather than admire him, are assholes.

The way he does it, though, it’s mesmerizing to watch. The rest of us should probably just take up gardening.

Ethan Chiel is more afraid of you than you are of him. He’s also on the microblogging website Twitter dot com: @ethanchiel.

In My Other Life, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2016.

How To Be A Dancer

In my other life I am a ballerina.

When I was two, my parents took me to see the New York City Ballet production of the Nutcracker. The room went dark, but I wasn’t scared. I saw the bodies on stage fluttering and catapulting, all arms and legs and story. I didn’t understand that I wasn’t part of their euphoric twirling, so I got up from my seat, spun around, and joined in. And after not very long I was, in fact, very much a part of the show.

In 1810, Heinrich von Kleist suggested in an essay on marionette theater that “grace appears most purely in that human form which either has no consciousness or an infinite consciousness. That is, in the puppet or in the god.” And there I was at two, Bunraku Baby, lifted by strings to dance. I’ll never be more graceful than that.

Recalling the delight of my debut (I got applause, naturally), I think I am able to understand where the pleasure of dance comes from. It’s somewhere beyond consciousness, combining the great parts of other art forms, with motion and catharsis. It is silent and musical, expressive and abstract, ancient and immediate, athletic and theatrical. Set it to piano or drums or chanting, and people are transformed into spirits.

Like so many kids, from the time I went to see the Nutcracker, I wanted to be a dancer. I had several teachers, but the one I stuck with the longest was Miss Alexia, a tall, thin Texan who had maintained her accent after years of living in the Northeast. She mostly talked about George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins, for whom she’d danced as a company member of the New York City Ballet. After having had a successful career as a ballerina, she moved to my small town in New Jersey, and proved herself to be a terrific choreographer of children’s dances. My mom once asked her if our production of Aaron Copland’s “Rodeo” had been adapted from a Balanchine show; Alexia turned red, grinned, and gently explained that it was Agnes de Mille who had made that ballet, in the forties, but this one was an original for our twelve-year-old class.

I was O.K. I could get my leg up high and I had good feet — I often got compliments on my arches when I tried on ballet shoes — but good feet will only take you so far. I could never land a killer triple pirouette; my balance was off. I was not “disciplined about my body,” as they say. I was always short, too chubby, too curvy. Lots of my peers hurled themselves into eating disorders, and my failure to follow, to my warped mind, demonstrated a lack of nerve. I wasn’t especially coordinated, and sometimes intricate choreography was lost on me. Alexia used to call me Sybil, because of my inconsistency. I remember her groaning, while I was in mid-flail, “What are you doing? Twyla Tharp?”

By then, I was dancing seven or eight hours a week — which is nothing compared to kids enrolled in pre-professional programs, who might dance seven hours a day — but this was the major commitment of my after-school life, and thus my childhood. And unlike peewee sports, with town recreational leagues, dance is not a default. It seems somehow out of feminist fashion to sign your daughter up—a son, maybe. Those who stick with it develop a particular identity, and an exceptional devotion. In addition to ballet, I took jazz, tap, and hip-hop (“Stop being so white!” my teacher shouted, to no avail), and so did the other girls in my group (we were all girls). Some of us were very good, but only a few were encouraged to audition for the School of American Ballet or Joffrey. The rest of us flapped along from one recital to the next, getting a little better and receiving bouquets for our efforts. Every year we learned more of what we would never truly master.

Occasionally, my mom would bring me on the bus to Manhattan, holding my hand from the Port Authority to 57th Street, and I’d drop in for a big, open class at Broadway Dance Center. Sweating among professionals in those studios, I had my moments, at twelve and thirteen and fourteen, of knowing how it feels to be promising. But puberty ended that. It became obvious that I was never going to be a real dancer. I could have invested more hours in class, but what would have been the point? I’d never really be good enough, or have the right shape. It was time to grow up, and try something else.

Before I stopped entirely, I scaled back, and masked my disappointment by becoming the class clown of ballet. I wanted everyone to know that I was just there to have fun. If I couldn’t be the most talented girl in the mirror, I’d be the jokiest. The only one I failed to convince was myself, and when I went to college, I decided to pretend like that I’d never danced at all.

“The only sin is mediocrity,” Martha Graham said. For dancers, either you’re the chef of a five-star restaurant or you’re nothing; there is no home-cooking. “You don’t just dabble in it,” a now grown dance kid told me. Jenifer Ringer, who started as an apprentice at the New York City Ballet in 1989, when she was sixteen, left when she was twenty-three. She had gained weight, gotten injured — human responses to a super-human endeavor. “When a performance wasn’t absolutely perfect, I took it as a sign that I was a horrible dancer and a horrible person,” she explained to the New York Times. She went to college, and waited to miss dancing, which took three months. Then she signed up for a class at Steps, where, she said, “I felt like a 10-year-old again, dancing just because it felt good.” Ringer returned to City Ballet reinvigorated — “I feel so free on stage” — and was promoted to principal dancer. When she retired, in 2014, the Times reviewer remarked on how young she looked in her final performance.

The tension between the pure pleasure of dancing and the arduous discipline of honing technique can be debilitating, because it’s both physical and cosmic. Dance is about freedom, yes, but it’s also, obviously, about control. “It’s hard,” a teacher once told me of her young students. “I want them to get free, but they also have to learn.” Governing your entire being, for a purely aesthetic sake, demands rigor. “I treated it like a profession,” another childhood dancer said. In “Apollo’s Angels,” a phenomenal book by the dance historian Jennifer Homans, you can follow an early lesson plan for ballerinas at the beginning of the nineteenth century: “49 pliés followed by 128 grand battements, 96 battements glisse, 128 ronds de jambes sur terre and 128 en l’air, and ending finally with 128 petits battements sur le cou-de-pied.” Marie Taglioni, who is known for being the first person to go up on pointe, would practice by holding a pose for a count of a hundred, and before bed she’d work on her jumps — Homans describes her building strength in her back and legs by touching her hands to the floor without leaning over, and then pushing herself up on pointe.

The model for the body that can perform this way, Homans writes — feet turned out 180 degrees; lifted torso; lean, muscular extensions — is that of Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, whose proportions are designed according to the elegant geometry of God. The female dancers I saw when I was growing up — Darci Kistler, the models in catalogues, images of the divine — did not look like me. But intellectually, I figured, I could relate to them, because the ethos of dance isn’t about simply achieving perfect form, it’s in the practice itself: the repetition of 49 pliés at the barre, and again at the center of the floor. This is what dancers believe in, commit to, endure, conquer. You need to have the right body, but you’ve also got to have the mettle.

If Jenifer Ringer couldn’t make it out unscathed, how could any of us regulars? One summer, my dance studio flew in Vadim Pisarev and Inna Dorofeeva, a married pair of principals at the Donetsk Opera and Ballet Theatre, to teach us for a week, and my class was forced to sit through a ten-minute diatribe against fat. “How can you go out and eat and then come in and dance? You have too much Veight!” They were concerned that we didn’t take our training seriously enough. The lecture was directed at one girl in particular, who sat cross-legged at the end of my row, but we were all unsettled; it happened just before lunch. The girl on the end did not eat hers.

Recently, at dinner with two friends (pasta and cake), I wondered aloud, “Is dance something you are or something you do? Are you a dancer if you haven’t been dancing?” One said, “There’s something ingrained. Everyone learns to write, but not everyone learns to dance.” The other agreed, and told me, as both a blessing and a warning, “You chose it.”

In the old tribes of Madagascar, when the men went off on a headhunting expedition in the jungle, the women had to perform a dance until they returned. The sociologist Marcel Mauss wrote that, among the Dayaks, women would rise at dawn, pick up weapons, and begin moving ceaselessly; “all those Dayak women, dancing and carrying sabers, are really at war,” he observed. “Acting this way, they actually believe the success of their ritual.” That is, they believe that their dance is magic.

There is sorcery to dance, and it worked on me as a toddler, and it works still. You enter a designated space, where the light is different, and you’re transported into an altered state — these are the conditions for going into a trance. A couple years ago, I was at a performance of “Who Cares?,” a Balanchine ballet set to sixteen Gershwin songs. Occasional audience members of City Ballet, like me, may not be able to catalogue all the Balanchine program staples, but “Who Cares?” stands out for being the jazziest, and for being the one most likely to elicit a wavering, mumbly, sing-a-long. At the performance I attended, the karaoke was intermittent and subtle, but there was another sound effect: What I heard, over Gershwin’s melodies, was approximately an orgasm. The happy customer was in the row in front of mine, so I could see clearly that there was nothing happening in her seat other than ballet-watching elation. She saw the sturdy arabesques and the confident lifts; she wiggled her toes under her chair, clutched her brooch to her chest, and let out a series of oh’s! and gasps, culminating in an enthusiastic round of applause.

I have always taken pleasure in watching dancers perform, though not quite like that. Those who cannot do, do vicariously. If, at two, the distinction between watching and participating was beyond my understanding, it began to evolve into its own kind of meaningful erasure. A wannabe going to the ballet can will herself into a daydream. This isn’t sleepy, but almost like an exercise: by seeing the movement, and appreciating it deeply, you might, in some way, join in. You’re a third person floating into a pas de deux, practicing in your head. And in fairness to that woman sitting in front of me: watching the realization of what, for you, would have been impossible, can come with mad longing.

“Do you ever wonder if it was a scam?” one of my dance-kid friends asked. Like an elaborate trick demonstrated by suburban dance schools around the country: give us a decade, and we’ll make tens of thousands of dollars vanish into stage smoke. Classes, tights, leotards, shoes, recital costumes, recital videos, dance team entry fees, dance team sweats. If the purpose of a dance education is for making dancers — not in some remote, aspirational way, but as a matter of practice — and most children won’t wind up hacking it, what is the point? Exercise, discipline, a sense of timing — there are other means to those. To put on a show for our parents?

“I feel weird talking about it,” my friend went on. “Even the term: ballet mistress. She wasn’t a scary Russian lady. She was in some off-Broadway shows. She was just in small-town America and she was training us as if we would become these great ballet dancers, even if none of us would.” Then she said, “I’m embarrassed I ever thought I was good.”

The magic that happens in a dance class is that you believe the success of the ritual. You see yourself making yourself good — we all do it, because we’re supposed to. Why else would we be there? Sometime after I’d concluded that I would never be great, what followed was that I wasn’t any good, and the spell was broken. I had to ditch the longing — turns out that it was a shameful waste of time, a delusion. I put it out of my head: all of the pliés and grand battements and petits battements sur le cou-de-pied. And I made that part of myself disappear.

A few words about feet: Dancers’ feet get dinged up pretty bad, professional or not. There are many gruesome ways to describe the ramifications on individual toes, the ball of the foot, and the heel, which suffer from blisters, bunions, Achilles tendonitis, and other pains. When I first started with pointe shoes, all us girls would show off after class by scooping out our lamb’s wool toe pads and comparing the bloodiest. A toe pad is placed around the top of your foot like a mitten; many manufacturers make a gel version, too, sometimes called an “Ouch Pouch,” but good dancers tend to avoid them, because they’re too thick and you lose the feeling of the floor. A dance shoe is supposed to mold to the foot, like a second skin, and the more you’ve got covering your feet, the clunkier your steps will be. Dance supply stores also sell silicone individual toe tubes (“Jelly Tips”), which are more like gloves, but you can choose to slide them on only certain toes. I would often use these on my big toes, and any others that might have had a particularly nasty-looking blister, but then I’d try to forego the lamb’s wool.

When I was at my peak dance-hours, my feet started to seem like horrible obtrusions on my body. They looked generally purplish. I kept my nails short, and for obvious reasons I never attempted a pedicure. I avoided open-toe shoes, and when I wanted so badly to wear them that I convinced myself that my feet weren’t really so grotesque, I would show up at school and immediately be mortified, and have to wait until I’d forgotten the hallway humiliation before I tried again. Then the worst thing happened: I completely lost the toenail on one big toe, and then the other. (Actually, after a couple classes, I forced myself to complete the symmetry; had to be done, a loose toenail is like a loose tooth.) This is a rite of passage. Real dancers dance through it, proudly, under the belief that, ultimately, toenails are only getting in the way.

When I stopped dancing, my feet gradually softened. After a while, the last evidence of damage healed. The summer before I started college, I bought my first pair of flip-flops, which I wore around the dorm with preposterous glee. I still catch myself admiring my feet, intact and unremarkable. I give myself pedicures because I can. Having gnarly feet is something I never started to miss about dance.

One Saturday afternoon, I went to see my friend Adrianna Aguilar and her infant dance company, Trees, perform a new show. The event was supposed to take place outside, at a park in Bed-Stuy, but we were expecting rain, so word went around that the setting had changed to a spot nearby, with only a street address. Upon my arrival it was clear this was going to be at someone’s apartment. I went with a non-dancer friend, a kindergarten teacher. We buzzed in. Someone had not picked up his newspaper; we left it by the entryway. Inside, we ascended four flights of plywood stairs, which looked to have only recently been nailed together. At the landing, people had taken off their shoes and left them outside the door. We kept ours on. Adrianna let us in, with a hug and an offering of snacks that were arranged on the kitchen island, which was also the middle of the stage. Chairs were positioned against the walls, and there was a big open space to the right of the refrigerator. A guy sat at the base of the fridge banging on a metal pot. We found seats by Adrianna’s mother. “She was dancing when she was pregnant with me,” Adrianna said.

The pot-player began to wind up. Next to him, a young woman with her hair tied in two perfect buns, like Princess Leia, began to tap-dance a beat on a slab of wood. A man with long dreadlocks and a woman in a woodland-design tank top moved to the center of the room, and began to sway. My friend leaned over and whispered, “This is going to be immersive as hell.”

But nobody touched us, nobody asked us to participate. The woman sitting on the floor beneath my feet got up for the second movement, an intense stand-off with another woman; the two had nearly identical buzz cuts. At one point, a guy shuffled over for a glass of water, which was not part of the performance; later, Adrianna started eating a popsicle at her seat, which was.

There were lots of swooping arms, elbows jutting out, writhing on the floor in a move that I recall as a sexy seizure, and quite a lot of pushing and spinning someone into submission, down to the ground, aikido-style. Some of this was hard to parse. There were moments when I looked around curiously to see how others were reacting (lots of mellow grins; I caught water guy mid-chortle). But there were as many moments when I watched these people — twenty-somethings from Brooklyn and Washington Heights, dancing around a refrigerator — and felt as if I had been let into something more intimate than a show. There, in the kitchen, I had the sensation of walking through a door that I wasn’t supposed to have opened, and, upon entering, being welcomed in. This was not dance as I’d known it, but the people I saw were unafraid of letting me see them try something new. When they were finished, I felt admiration and envy. They had found for themselves a way to move.

Erick Hawkins started his career in the inaugural class of Balanchine’s School of American Ballet, met Martha Graham, married her, divorced her, got into Buddhism, and choreographed a show about a July Fourth party called “Hurrah!” His productions included “Early Floating,” “Naked Leopard,” and “To Everybody Out There.” (Dance names are weird.) He was famous for saying, “The body is a clear place.” That was the title of a book he published in 1992; ballet is a “diagram,” he wrote, in which “too much of the indescribable pure poetry of movement had to be left out.”

Language and dance are allies, but exist in different hemispheres. If ballet, the root, is like Latin or Greek, nearly all dancers are expected to be fluent, even if only to apply the terminology to new forms. This is why many dancers know some French, or at least useful conversational phrases like saut de chat (jump of the cat), pas de cheval (step of the horse), cou-de-pied (neck of the foot). The aim is for the steps, when realized onstage, to become so fluid and specific that they become something else, as individual letters are to a poem. Hawkins, my friend Adrianna — and most interesting choreographers these days — got somewhere by learning other languages, but they all had to study the diagram.

It didn’t occur to me until I started working at literary magazines that my childhood ballet teacher, Alexia, had been a brilliant describer. Great dance teachers, like great writers, distinguish themselves through evocative language. How can one learn to move the body in a precise way, so that your back and neck and legs and arms and feet are positioned exactly as they’re supposed to be? So that your mind doesn’t intervene, and topple you over? There were many times when Alexia would come over to me and move my hips or shift my shoulders, but even more often she would say something like “Imagine that there is a string holding you up, and you’re a marionette.” And I knew in my body exactly what she meant.

Other great metaphors I have heard: “You know those ringed red-and-white spinning stripe signs outside barber shops? Imagine that’s your turned-out thighs.” “Every movement is a photograph.” Adrianna told me about a time when she was in class, and a teacher said: place your foot in cou-de-pied like you’re caressing your lover’s face.” Adrianna tried her best, but soon the teacher walked over, raised an eyebrow, and said, “You’ve never been in love.”

This was the profession I found myself in as an adult, reading copy and wondering about the best ways to express ideas. I took to in it much the same way as I had with dance: when I read, I am lifted. But this I could do while eating a sandwich. At various points over the years, I fact-checked, researched, wrote, made comments on structure. Sometimes I sat at my desk and believed that I’d made it — like when I was two, and I was part of the show. Much more of the time, when my suggestions were tossed aside, or my pitches were trashed, or my prose failed to impress, I sensed that I was merely spinning in darkness, adjacent to the real talent. But I couldn’t pretend that this was some childhood lark; mastery didn’t depend on being lithe.

One day a few years ago, I was summoned by an editor to answer a ballet question for a caption. By then I had apparently let slip that I had been a dance kid. He called me over, pointed to a picture of a ballerina, and asked, “What’s she doing here?” I looked and immediately melted. It was the most elementary query. Anyone who has ever taken ballet should be able to identify the steps; it’s basic diagram stuff. But when I looked at the image my mind was totally blank. Her leg was in the air — not arabesque, what’s that other one? I had the sensation of having lost the ability to speak a language that I had known as a child. “I forget that one,” I said, pathetically, lobbed some dumb joke — I was still good for being the jokiest girl in the mirror — and rushed away.

Back at my desk, I sat staring at my computer screen, my brain sputtering. Was this my first encounter with severe memory loss? But I was twenty-five! How could I have willed myself to erase dance so completely from my mind that, when trying to recall the name of a simple position, I came up empty? It was as if, after having determined to extricate myself from the person I’d failed to become, I had sacrificed a decade of earned education. I sat for twenty minutes, confused and remorseful. And then, finally, out of the farthest, rustiest cabinet in my brain, I retrieved the word: attitude.

Other people do not get hung up about their childhood pastimes. They join a pick-up basketball game or buy a piano, and even if it doesn’t come easy, it’s fine. They find some way to transition from kid play to adult satisfaction. Dancers, on the other hand, are never really playing. They are striving in a room full of strivers. And it’s possibly because of this that adult dance classes always bummed me out. Who were these losers? What could they be striving for, at this point? There wasn’t even a recital to prepare for. It wasn’t just me. “I felt like, if I was dancing, I was training for something,” one of my former dance-kid friends said. “If I didn’t have a show, it didn’t seem like there was a reason.”

There is something odd about dancing without performing, sort of like hitting the batting cages without ever playing baseball. But now that I was a dance amnesiac, I started to get curious. And now that I was striving for other things, I wondered what it would feel like to strive in a dance class for its own sake. My failure to become a dance virtuoso had already passed me by. Maybe in my age of advanced concerns, it would be O.K. to just be O.K. Balanchine would have approved, I thought, since he was known for saying stuff like: “Why are you holding back? What are you saving for — for another time? There are no other times. There is only now. Right now.”

When my birthday came around, my boyfriend — a strong receiver of hints — gave me a gift certificate to take five classes at a studio in Brooklyn. I sat on it for five months, psyching myself out. Then, finally, I used it. I decided to subject myself fully to whatever trauma might be merely lurking if I attempted some other kind of dance, so I went for beginner’s ballet.

The first thing I had to do was get dressed. I had thought of this in advance, so the last time I’d gone to visit my parents, in New Jersey, I opened the bottom drawer of my old dresser and pulled out the single remaining intact leotard — I’d hacked up the rest, during a cut-up-my-clothes phase — and lifted my dusty dance bag from the back of the closet to find my ballet shoes. They were stiff, but still usable. I brought them back home to my apartment, along with a pair of pink tights, which I knew would make me look like a dork, but at every other ballet class I’d taken they had been the required uniform. To be safe, I brought shorts, too.

When I walked through the door to the studio on that first night, everyone was wearing shirts and sweats; the only person dressed anything like me was a tiny person with her hair pulled back in a tidy girl bun. Right away, I felt the dread of regressing in public. I took my place at the barre. Everything was where I had left it: the mirror, the gray Marley floor, the sequence of steps; it was only I who had changed. We began with a simple routine to roll out our feet, and then moved on to pliés, tendues, dégagés, and rond de jambes, all of which my body remembered before my brain did. It occurred to me that, months earlier, I might have been able to recall attitude much more easily if it hadn’t been a matter of naming a word. The “indescribable pure poetry of movement” is the stuff internalized without language — the feeling of a step. “Connect your belly button to your spine,” the teacher said, and we all shifted our posture. Then we got to grand battements. My legs felt like overstuffed suitcases that I had to carry over a subway turnstile. When I lifted them, I believed that I had made it to my old 125 degrees or thereabouts, but when I peeked, I hadn’t cleared 90. Then I thought: Something to strive for.

I went back the next week, and the week after that. When my gift card ran out, I bought myself another one. I came after days of work where I felt like I’d achieved nothing, and in class, I accomplished something. I invested in a second leotard. A few months in, when I had the nerve, I invited one of my fellow former dance kids to come along, and afterward she didn’t stick with ballet, but she started going to hip-hop. She still finds the performance void to be odd. “In the back of my mind,” she said, “I’m thinking, maybe something more will come of it.”

I started a new job, and left the beginner’s class. One night, I ran into Adrianna. She’d been taking three or four classes a week — always including one in ballet — but she wasn’t interested in the exclusive club of ballerinas. “Dance is a spectrum,” she told me. “I’m a dancer, you’re a dancer, too.”

Two years in, a new person came to class. She had her hair tied into a ponytail, and wore a purple tank top and gray leggings, with socks, not ballet shoes. The teacher asked, as she did every week, if there was anybody who might be unfamiliar with the steps. The new dancer raised her hand. The teacher looked around. “Let’s put you between two people you can follow.” She turned to me — me! — and asked, “Can you stand over here?” I breathed out a yes, and smiled deliriously. After barre, the new dancer shook her head, looking flustered, and said by way of apology to the teacher, “I haven’t done this for 16 years.” The teacher said not to worry, and flashed a generous smile. “We’ve all come back to it.”

In My Other Life, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2016.

The Real Carmen Freeze

In my other life, I wrote the puff pieces.

When I was 24, I was staying in Asheville for a few months to intern at a paper. I worked days at the paper and evenings at a coffee shop downtown. I wasn’t from Asheville — my parents had moved there a few years before, from Wisconsin — and I viewed my time there as temporary. This was all a long time ago — 1995. I had long hennaed hair, knocky teeth, and a voice so soft and apparently young sounding that when people phoned the paper they often thought they’d reached me in error. “But I want to speak to Carrie Frye.” “I am Carrie Frye,” I’d say, until eventually — on the third round or so — they believed me. I wore Adidas and a swingy miniskirt everywhere, and I had a degree from a college in Massachusetts that qualified me to be the sort of person who maintains vague but ardent plans of someday writing a book about the poet Frank O’ Hara. I had a small white dog named Sid I’d adopted as a stray in Austin when I’d lived there after college. The plan was, as soon as I had enough experience (that is, a resume more cohesive than “Golden Nozzle Carwash,” ‘Fort Worth Mortgage Company” and “vague but ardent plan to write a book about Frank O’Hara”), Sid and I would move to New York and I would get a job in publishing.

“The paper” was actually three papers, all monthlies. There was a business journal covering Western North Carolina; another one, for the upstate of South Carolina; and an arts journal. I had chosen to intern there by the careful selection process of “they would let me.” I feel I should emphasize here that it seemed like a legitimate place to work. It was small, yes, but there were big glassy offices and staff and ad people who, between phone calls, would stand on the sidewalk out front to smoke and gossip furiously. Or there was when I started. Two months into it, some sort of radical tumult happened and I found myself not an intern, but the papers’ editor, and I’d been installed in a little shoebox of an office on the sixth floor of an old, then dilapidated building downtown called the Flat Iron Building.

The office was a sublet in a suite of rooms belonging to the designer who laid out the paper. His name was Lowell, and I thought he was grim and disagreeable. The first time we’d met was when he’d visited the old office to do some darkroom work, and I had been nipping into that same room to heat up my internish lunch. I had said something like “Can I do this before you get started?”, and he said “No” and shut the door in my face. Then stayed in there FOR TWO HOURS. (We are now married.)

After the switch, I saw the paper’s publisher — I’ll call her Jessica — only two or three times a month, when she’d drive up to Asheville from South Carolina in her enormous SUV. She was in her 30s, had beautiful hair, and always wore the bright red suits and shiny heels of a predatory species of charismatic megafauna. We had nothing in common outside of work but I remember finding her entertaining, mostly. I enjoy flashiness and bravura, and she had a lot of both. If she sometimes lied — and you could tell when she was because that’s when she’d make the most intense eye contact — it felt un-malicious in intent. She seemed to like me well enough too. She would at least call to say things like, “I just gave the printer a check. MAKE SURE YOU DEPOSIT YOUR SALARY THIS MORNING.” If she was in town for the day, her assistant would come too, as well as the remaining ad exec, and the three of them would swirl around the outer office, making phone calls and gossiping furiously, and then they’d all leave, and it’d be quiet again.

The idea to use the name ‘Carmen Freeze’ came about with either the first or the second issues I edited. I had a small budget for freelancers, but I was responsible for the rest of the content, and I got it into my head, somehow, that it would look strange if half the articles in the three papers were written by Carrie Frye. So I invented the byline ‘Carmen Freeze’ to carry some of them. I thought it would look better.

The first article Carmen wrote was a puff piece about a home-goods store in South Carolina. I remember this one very clearly, even after all this time, because I noticed only a couple paragraphs in that Carmen was a better writer than I was. More elegant and light footed. She even punctuated better than I did. It was the strangest thing, like if you thought you were okay but a little plunky at the piano, and then one day, you could sit down and play beautifully, your hands rolling up and down the keys, but only if you called yourself Gigi Rachmaninoff. I wasn’t the only one who noticed either — people frequently called to ask for Carmen’s contact info.

After that first article, Carmen was assigned a couple pieces per month. I had some rules about it. She couldn’t write anything “reported” or a big feature story, as I thought those should go under my own name (I maintained a careening sort of ethics), but she could write puffs and other little features. A friend who’s asked to go by Elena here began to work part-time for the paper too, and she volunteered another of her aliases, ‘Hortense Brood,’ for some of her articles. She also gave the main paper the nickname by which I still think of it: The Blue Ridge Blowjob, even though at the time I was quasi-offended. (It might have been The Blue Ridge Blowjob, but it was my The Blue Ridge Blowjob, et cetera.)

Elena plays a part in the other anecdote I wish to tell you about this period. As I’ve said, the papers were monthlies, and they all went to press together. The week before was always brutal, no matter what. I’d work all day, flit out at dinnertime to grab something to eat, then hurry back to the office, to write articles and type in dumb business journal back-pages-type things until three or four in the morning. I was usually very fond of the Flat Iron Building. I liked the hand-operated elevators, and the two elevator operators, Ruby (mornings) and Janice (afternoons). I liked the way the smell of perms hit you as soon as you walked into the lobby, because of a beauty salon on the second floor. I liked the doors of the offices with their frosted panes of glass, like you’d expect to see for a detective agency. I liked the mysterious business names, and the way people ducked in and out without ever looking up or saying anything friendly. I liked the building’s deep well of quiet. All the same, I found it incredibly spooky at that time of night, when I was the only person still there. Or as I thought of it: the only person there?????????

The bathroom on our floor was two hallways away. The stall doors were high and wooden, like confessionals, and, when it was that time of night, I lived in fear that I’d hear the bathroom door start creaking open when I was inside one of them. It would have made a terrible Hitchcock movie: the lone business journal editor, stabbed or strangled in the Flat Iron john, her last words: “I. haven’t. finished. typing. in. Wachovia’s. profit. report.” Afterward, I’d skate back to the office and lock the door behind me. I’d sleep in a sleeping bag on the floor, then get up around 7 to make coffee and get back to it. The building would fill back up, the perm smell would begin to waft up the stairwell, and my creeping Hitchcock fears of the night before would start to seem ridiculous.

One month, when we were even further behind than usual, Elena decided to stay over too. Another friend of hers also had an office in the building, she said, and we could sleep there. When we were done for the night, we went down a couple flights of stairs and around the corner. Same dim hallway lights as my floor, same layout, similar row of darkened doors. She stopped at one and got out a key. When the door opened, I realized I’d been half-expecting this office to look like mine. It didn’t. There was no desk furniture, no computer, no beige carpet. Instead the room was filled with all sorts of odd, beautiful animal statuary from different parts of the world, and giant cushions — piles of them — for sitting on the ground (or, you know, sleeping on), and twinkling little lights. It was the strangest and most tranquil place. It’s what I’d wish for every writer on deadline, that they’d stumble into a room like that and get to sleep there a while.

I didn’t meet the friend the room belonged to until some time later. He was polite but aloof, in a way that made him hard to connect with the marvelous surprise of the room and how well I’d slept there. But that seems right too, for a story about one’s mid 20s: That there’d be all these different doors leading different places, and it wouldn’t always be clear which person matched up to which door, and which one ultimately would be the right one to go through.

Carrie Frye is a writer and editor living in Asheville, NC. She’s working on a novel about the Arctic and writes the Black Cardigan newsletter on the side.

In My Other Life, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2016.

Etymologies

In my other life, I’m a Roberta.

“Jacqueline” was the 54th most popular name for girls born in 1983. The name had reached its peak popularity in 1964, the grieving Mrs. Kennedy an even worthier namesake than she’d been three years before. I was named for my great-grandfather, though my father was a subscriber to The Third Decade: A Journal of Research on the John F. Kennedy Assassination, so we can’t discount Camelot’s influence entirely. Sometimes, however, my mother liked to tease me by reminding me that my parents had nearly named me Roberta, which was the 475th most popular girl’s name in 1983. In a nasally singsong voice, she would say, “We would have called you Bobbie,” which usually made me shriek in horror.

Roberta, of course, is a fine name, carried with great dignity by Roberta Flack and whoever the other famous Robertas are. Had I been born a decade earlier, I like to think that Bobbie would have served me in good stead in the waning days of lesbian separatism, though I suppose that Jeff Goldblum might have it that naming a baby Roberta in 1973 would produce a different hurricane entirely. It’s the chaos theory of baby names. Jeff Goldblum would not be wrong. Had I been born in 1973, Roberta wouldn’t have even made the list. My dad’s brother hadn’t driven off of that bridge yet, and Jews generally don’t name their children after living relatives. That takes Jacqueline out of the running, too: my great-grandfather was still alive. This is the chaos theory of life, which is death.

In 1983, though, Roberta would have been something like a necronym. His brother and his parents had only recently clawed their separate ways back to the living, where the pain of a future without Bobby could be eased by their dreams for mine. If naming were an astrology, a prophetic science of history and hope and old light, Roberta, bright fame, might have returned to them that lost, shining son. But grief eases, and I was named Jacqueline, supplanter, which I was: Bobby’s crown had been meant for the boy my mother had miscarried the previous year. No family becomes less complicated with time.

I told my therapist this story the other day, though I’ve told it before in a hundred different ways. She sighed kindly, as she does when I return to old wounds. “There was never any hope,” she said. There was never any hope that they could be saved, she meant, and I knew she was right; the ache in my chest bloomed in an instant, a flower in a time-lapse film. How could they have loved me when they were already grieving all of the people they had hoped I would become? People are contingencies, too, and the names we’re given — all of them mean chaos.

Forgetting this is a fervent private practice, but also a communal devotion. In this shit year — or, more honestly, in this noxious world we’ve built — there’s more to say about names, both proper and improper. We believe that what we call things matters to what they become, but the fact of the belief might matter more. Divinations and incantations and prophecies are always already curses of some kind. The personal is political, but the interpersonal is, too; things happen to us, and we happen to each other.

It’s funny and tender to me that the principles of time travel, the ones we’ve made up, offer consolation instead of relief.* We reach back for fantasy, but we make the resolution the truth: going back would only place you on a different path forward. This is the order of things.

No one has ever called me Jacqueline; only strangers do, and that seems right. It’s the name of someone they don’t know yet. Only I can tell them what it means.

*Theoretical physics stans, don’t @ me.

Jacqui Shine is a writer and historian.

In My Other Life, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2016.