Indicators That the Book Party Scene on HBO's Forthcoming Lena Dunham Show "Girls" is an...

Indicators That the Book Party Scene on HBO’s Forthcoming Lena Dunham Show “Girls” is an Unconvincing Approximation of the Real Thing, as Conveyed to Me by a Former Book Editor Working On-Set as an Extra (“Publishing Executive”)

by Marissa Walsh

11. The pervasiveness of eye shadow.

10. A The Situation/Vanilla Ice look-alike in shiny jacket, aviator sunglasses and jauntily tilted hat.

9. General lack of pastiness.

8. None of the following were present: Colson Whitehead, Sloane Crosley, Sylvia Miles.

7. And yet: a racially proportioned crowd.

6. No Housing Works tote bags.

5. Loud colors.

4. The author’s writing professor from college was present.

3. The author’s writing professor from college was played by Michael Imperioli.

2. The fictional author’s publisher paid for the party.

1. Only six people wore glasses.

Marissa Walsh is a literary agent and author.

Stupid Moon Was Actually TWO Stupid Moons

“Earth once had two moons, which merged in a slow-motion collision that took several hours to complete, researchers propose in Nature today…. A previous collision with a smaller companion could explain why the Moon’s two sides look so different.” Or maybe the moon’s two sides look so different because the moon is a STUPID PIECE OF SPACE ROCK. Lick my left one, moon.

Again With The Bronies

You guys are bound and determined to make ‘bronies’ happen, aren’t you? “There were healthy conversations about how cool the show was, or the importance of nostalgia. And then on the other hand there were pictures of big black dicks and dead horses.”

A Q&A With Amy Klein Of Titus Andronicus

A Q&A With Amy Klein Of Titus Andronicus

by Kevin Lincoln

A literate, anthem-prone punk band from New Jersey, Titus Andronicus put out their fantastic second album, The Monitor, in 2010. Shortly after its release, multi-instrumentalist Amy Klein joined the group to play guitar and violin; she also brought along a fierce and charismatic personality that plays a big role in making Titus’ live shows some of the most riveting in contemporary music.

Between shows for another project of hers, Hilly Eye, I sat down with Klein at Cafe Lafayette in Brooklyn to discuss climbing on top of speakers, Patti Smith, Joanna Newsom, why everyone should read

Rat Girl, and Girls Rock Camp, where she volunteers as a counselor.

The two solo albums you recorded before are chamber-music type stuff, and Titus Andronicus is pretty much punk rock, and Hilly Eye is hard but not hard in the same way that Titus is hard. Is it just natural for you to write songs in a lot of different registers?

Well, I’ve always wanted to be in a rock band, and I’ve always loved punk music and noise music. And I’ve always appreciated the power dynamics of music, particularly when it comes to gender roles, when you can have a woman who is making unconventional noise and has a very powerful dominant persona on stage — I think that’s amazing, I’ve always wanted to do that. I started doing that in college. I had a band in high school but I wasn’t in control of the songwriting, and I started developing my style when I was in college as far as rock music. And then, somewhere along the line, I got really obsessed with Joanna Newsom, and I decided that it would be fun to write folk songs. I would perform them at coffeehouses in college, stuff like that.

You’ve been playing a lot of Hilly Eye shows this week, right?

Actually, tonight is the last show we have scheduled for a while. It’s in Philadelphia, but we’ve mostly been playing around the city. I had one show with a new band, which is, like, songs that I recorded by myself and then my friends heard them and were like, “Oh, we want to play these songs,” and now we have a band. It sounded really good, I was happy with it! Our tentative name is “Amy Klein and the Blue Star Band.”

What are the origins of that name?

That comes from Just Kids. Have you read that book?

Patti Smith, right? No, I haven’t.

It’s really good. It’s about her friendship with Robert Mapplethorpe. When they first met, they were both into William Blake, who I’m also very into. And William Blake did all his own illustrations for his poetry — he was also a visual artist — and I guess they both had something that they found in his work, because Patti was more of a poet, and Robert was more of a visual artist, like a painter, when they were young. There was a line in one of [Blake’s] poems about a blue star that was a symbol of innocence, and then it had a really beautiful illustration, too. So that was like their code-word, and whenever in the future they’d write each other letters or postcards they’d sign it blue star, or they’d have an allusion to a blue star. In the book, it’s a symbol of the way that they were when they had just moved to New York, and their youth and their friendship. I thought it was cool, and I also like the sound of it — it sounds a little bit country, like Big Star. Some of the songs that I have are a little Neil Young-inspired, they have a little country in them.

You have some serious diversity in the type of music you put out.

I like lots of different music, it’s true. I did college radio, and one of the great things about my college radio station is that they forced you to listen to a lot of different records, and you had to report back. Before you could get your own radio show, you had to prove that you were worthy of it. It’s true! They would give you listening assignments, to a different genre every week, and you had to write an essay about your listening experience to the particular genre. Then you would have a lecture and have to talk with people about it.

Was this a class, or just the radio —

No, this was just the radio station! It was pretty serious.

No kidding.

Pretty serious stuff. And not everybody made it on. I think ultimately it was more about proving your commitment; whether or not you had brilliant things to say about the music, that didn’t really matter. It was more that you had to show that you were really dedicated to listening to a lot of music and learning about music. So I feel like, yeah, in college I was exposed to a lot of different kinds of music and I still love a lot of different kinds of music. I think most people are that way.

Where’d you go to school?

I went to Harvard. That probably explains why the radio station was like a class.

I went to a Titus Andronicus show in April 2010, and you sang a cover of “Rebel Girl” by Bikini Kill, which was so cool. Does the band do that frequently? Because that was the only time I’ve seen you do that.

We don’t do it all the time. We usually have played it in D.C. because that’s where the song was written, and it has an association with the D.C. punk scene and Positive Force and all that. This year we started doing “Oh Bondage, Up Yours” because Poly Styrene died, so we’ve done that, and that’s the other one where I get to sing a cover. It’s a similar sound, it’s super confrontational [laughs], and I get to scream a little bit. It’s really fun. I really like to sing.

I think a lot of times what makes a performer really fascinating and what makes a performer seem powerful is if you see someone overcoming fear or overcoming weakness.

It had such a good energy to it. I remember you got on top of one of the speakers and it was so punk rock.

Sometimes you gotta do it. You’ve got to get on top of a speaker! What would they be there for if not to climb them once in a while? …

For me, it’s like… How do I explain it? I sometimes feel like I have two sides to myself, where I have a very sensitive and emotive side, which may be more suited to lyricism and poetry. And then I have a very type-A dominant side, which is what comes out when I do punk. Hopefully, where I’m headed as an artist is being able to combine them. I do think there is a lot of overlap, though. I think a lot of times what makes a performer really fascinating and what makes a performer seem powerful is if you see someone overcoming fear or overcoming weakness. That’s a lot more interesting, to see vulnerability mixed with great fervor and passion, which I think is what a lot of people love about Patrick [Stickles, Titus Andronicus member], how vulnerable his songs make him appear. He’s totally baring his insecurities, and yet in doing so he’s a very compelling and powerful figure.

It seems like getting on stage would inspire fear in a lot of different ways: It’s fear of people watching, but it’s also fear of what you’re doing, and what it means for you to be doing it.

Yeah, I read this really interesting book called Rat Girl. It’s by Kristin Hersh, who was the leader of the band Throwing Muses, which was — they got signed in, I think, ’85 or ’86 to 4AD, which is now a big record label but back in the day didn’t even sign American bands, they were a British label. So, [Throwing Muses] were this bunch of teenagers who must’ve been signed when they were like 17 or 18 years old, living in Providence and then Boston, who wrote really, really strange, original experimental music that could loosely be called alternative rock. So this memoir is, basically, about the singer and guitarist Kristin Hersh and a particular year when she was 18. It happened to be the year when she was diagnosed with bipolar disorder, and she started experiencing mania and hearing things. Actually, after she had a bike accident, she hit her head and … she started hearing voices, which to her were complete songs. We think of people hearing voices, but she would actually hear songs, like melody and lyrics and all the arrangements, and that was her mental illness: hearing songs. The book is all about her coming to terms with being an artist and also coming to terms with the fact that she had severe mental illness. There are parts in it where she can’t sing, and she’s in the studio and she can’t record, she can’t do it because she’s afraid of all this evil that’s buzzing around in her head.

The most fascinating thing about that is that, obviously when you hear voices, it sounds like the voices are not you. But if they’re inside your own head, and they’re songs, they are you — they’re coming from you — so it’s she’s writing the songs subconsciously and then they’re coming out, but it can’t feel like her songs, I would think.

At the end of the book she maintains that she doesn’t write her own songs, that they just come to her from music, which is outside her. I watched this interview with her on YouTube — now she has three kids, she’s in her 40s — and she still says, “Oh, I don’t write songs, I’m just this receptor, and they come to me.”

I think a lot of artists feel that way. It’s about the unconscious, and from the Surrealists onward people were really interested in not letting your conscious self get in the way of your creative potential. I think that’s really true as far as writing songs. This is something I learned in college. I was a poetry major too and one of the best lessons I learned was, you don’t sit down and say, “I’m going to write a poem about this table.” [indicates table]. Because, we can probably think of three things to say about this table: it’s sitting on the ground, it’s hard and it’s flat.

And it shakes a little bit.

Yeah, ok, so we’ve got four! And then you’re like, “Shit, I ran out of things to say about this table!” But there’s no chance you’re going to have a good poem out of that. But if you sit down and you say, “I’m just going to free-associate for a while. I’ll start thinking about this table but maybe it reminds me of a tree which grows in a forest, and that reminds me of going to summer camp when I was a kid,” you know? Then you can go back and edit it and see that, oh, this poem is really about the passage of time from when I was a kid to now, or something like that, and you can cut out the parts that don’t fit. That’s a much more constructive way to create something than to sit down and think really hard about the table in front of you.

So the Kristin Hersh book was really interesting, because she was someone who was hugely talented, and was hugely different from everybody. She grew up on a commune with hippie parents and went to college when she was a teenager, she skipped a lot of high school. She had almost no friends, except for her bands. And then, like, she started hearing voices and seeing hallucinations and writing songs that really sounded like nothing else. She must’ve had a lot of fear and a lot of self-doubt, and the book doesn’t shy away from any of that stuff, which is really interesting. She’s such a good narrator, because she lets you know exactly how hard it was and how crazy it was to be such a genius. … She still makes music, and she talks about feeling possessed by something when she’s really in the zone when she’s performing or when she’s writing. She talks about feeling like she’s possessed by, she calls it “evil” — for real, yeah.

That’s a tough way to think about not only how you’re living, but the art that you’re making.

Totally. When you listen to the songs, you can sometimes hear that they sound strange — some of them do sound really creepy — but a lot of it doesn’t sound evil, a lot of it sounds joyful. I’ve been thinking about that recently when I perform. It really is true that, whether you think it’s evil or passion or some kind of emotional high, when you’re playing music the right way you should feel outside of yourself, you should feel possessed by what it is that you’re doing. Any musician can feel when you’re in the zone and when you’re not. It’s like being an athlete: sometimes you’re just not feeling it, sometimes you really are. But the fun and the magic really happens when you are feeling it, whatever you want to call it.

I was just reading the piece you wrote on your blog about seeing the Lady Gaga Rolling Stone cover and realizing that female musicians are always shown as static objects in these magazines, and how important it is that women be shown actually playing instruments and performing. It seems like performing would lead to a different kind of productivity than just, say, writing by yourself.

Performance is social, inherently, and it’s also political, because you have one person (or a small group of people) with a microphone who is telling a very large group of people what to think and how to feel. That’s very dangerous. I think it’s also something that we associate with masculinity: to get up there and tell people how to think. That’s a traditionally male thing. You even see it in stand-up comedy: it’s really hard for women to break into stand-up because you’re telling people when to laugh, and you’re in control of lots of peoples’ minds and instincts and reflexes. It’s the same reason why we think of political figures as male. So yeah, I think performance is political, and it’s really cool and important when women do it and do it well, because you can change a lot of peoples’ minds about what women are capable of.

People also respond to women in pop culture because pop culture is really cool and fun — like it’s fun to respond to it — and politics is not always so much fun. When someone sits from on high or stands at a pedestal and tells you, “WOMEN ARE EQUAL TO MEN,” you may not internalize it as much as if you see some really cool performer like Kathleen Hanna making it really fun and sexy and cool to be feminist.

There aren’t that many places where girls get told it’s okay to mess up and be loud and express yourself and be crazy and do whatever the hell you want.

This seems like a good point to bring up your work with Rock Camp for Girls.

Rock Camp for Girls is awesome, I’ve been volunteering there for six years. It’s a place where girls can go and learn instruments and learn how to be in a band. The thing is, there’s no musical experience necessary, although a lot of the girls have played music before. The idea is, 100% D.I.Y., anyone can do it, totally punk, anyone-can-start-a-band mentality. And the thing is that it actually works. Hundreds and hundreds of girls around the world, maybe thousands at this point, form a band, and five days later they’re playing an original song to hundreds of screaming fans. It’s all because there’s a really dedicated staff of female musicians who volunteer and give 200% support at all times.

Whatever a girl does is awesome, you can do it, you rock. It’s the most positive environment, and it really works. By day three there are all kinds of boundaries being broken. Lots of girls of different ages, different races, different economic levels, whatever, are working together and making awesome music, and it’s really a unique place, because there aren’t that many places where, say, a girl who gets free lunch at school is going to be collaborating, becoming best friends with a girl who lives in a fancy apartment on the Upper West Side. There aren’t that many places where 15-year-old girls are actively encouraging and supporting 8-year-old girls.

There aren’t that many places where girls get told it’s okay to mess up and be loud and express yourself and be crazy and do whatever the hell you want. When I think about it, there aren’t too many places like that for guys either. Such is the society we live in that we like to tell kids what to do and give them very regimented ideas of what’s acceptable. And when we teach kids about music, we usually tell them to play a certain way, and we usually tell them music’s about talent, not about spirit or heart. So yeah, it’s a really unique environment, and the goal is to build self-esteem and encourage girls to see each other as collaborators and friends throughout their lives, so whether or not they ever play music again, hopefully they take personal experience and personal growth away from the camp. It really works — every time I see the showcase concert at the end, I cry [laughs], it’s really beautiful, and most of the other volunteers are really emotional as well. If you give girls instruments and give them support and tell them they can play and they can express themselves and be powerful and loud, you’re going to see a lot of awesome music coming out of that.

They also have Ladies Rock Camp, which is cool. It’s only for a weekend, it’s like the condensed version. If anyone, for the record, wants to do it, you can go to either Ladies Camp or Girls Camp — Girls Camp you can be 8 through 18, and after that you go to Ladies Camp.

When you guys got up on stage at 4Knots, I remember you said something about the Screaming Females, and I thought that was really cool — trying to build camaraderie and promote bands that you like.

Screaming Females are amazing, and Marissa Paternoster has got to be the best guitar shredder I’ve ever heard. Not even joking. I don’t know how she plays so many notes, and they all sound so good. She also has really good guitar tone — like, she could play one note and it would still sound so good, with all the vibrato [imitates vibrato]. They’re also from New Jersey, and I think they’re a really great band. Maybe they’re a little more underground than Titus at this point, but they shouldn’t be, because they’re really awesome.

How did you decide you wanted violin in Titus? How long have you been playing violin?

That’s actually the first instrument I played. I started playing violin when I was three. I took classical violin lessons for a while. I think, for the first Titus album [The Airing of Grievances], I wasn’t in the band but Patrick wanted violin on it, and he asked me to do the violin parts so I went and recorded them. Then, I wasn’t a member of the band until after The Monitor, so there was a lot of violin on The Monitor but I didn’t play it.

How did you end up in the band? Did you know Patrick?

I was in a band called the Sinister Turns when I was in college. My friend was in that band and she introduced me to Patrick. He sometimes played with us, he recorded on our EP, and then he asked me to do the violin for the Titus album. I wasn’t in the band until almost two years ago — I had a job in an office. I ran into Patrick at a show, I hadn’t seen him for like, many years, and he was like, “Do you want to be in Titus Andronicus?” I thought he was joking or something, so I was like, “Uhh, sounds fun?” Turns out he was serious, so I said, “Ok, I guess I’ll be quitting my job and going on tour!” It was pretty random, actually. I think the violin adds something, though, because particularly during the quieter, more mellow sections, it adds a touch of sweetness, and there’s some country feel and some Irish feel to a lot of the songs.

More than most other punk bands, Titus Andronicus has that sweet quality to them. A lot of it comes from how open and genuine Patrick is. Just him singing about his antidepressants and “the robot inside me,” that sort of thing, and the violin really works well with that.

There’s a lot of dynamic range in the songs, particularly the longer ones, they build a lot. We focus on things like dynamics and contrast and things like that. The tendency with punk is to go in hard, go in fast and then get out, so at this time it’s like, well, maybe we’re not really a punk band, you know? Maybe we’re doing something different.

Kevin Lincoln wishes he could play guitar; instead, he writes about culture and sports for GQ.com and other places. You can follow him on Twitter.

Interview condensed, edited and lightly reordered.

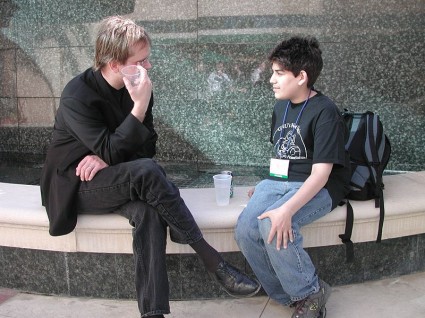

Photos by Bek Andersen.

Silvio Berlusconi: Diddling While Rome Burns

You cannot keep the Italian prime minister down: “Despite the Italian economy being on the rocks prime minister Silvio Berlusconi has reportedly held another controversial bunga bunga party this week.”

It's A Beluga Mariachi Kind Of Day

And now, this: “Hi there, my name is Eduardo Rocha, the Mariachi guitar player from this video. I believe that the name of Mr. Beluga is Juno and is a male. About the question if Juno heard us through the glass in this case I would say no because is pretty thick but he heard us through the air -water because the sound travels better in the water and the pool was open at the top. Take care.” [Via]

Was Aaron Swartz Stealing?

Was Aaron Swartz Stealing?

Since the July 19th indictment of Aaron Swartz for surreptitiously whooshing nearly five million JSTOR documents onto a laptop concealed in an MIT network closet, there’s been a lot of codswallop written about JSTOR, about Aaron Swartz and about the public’s right to access documents in the public domain. A 24-year-old computer prodigy and political activist, Swartz has been caricatured as either a hero or a villain; likewise JSTOR. The U.S. Attorney for Massachusetts, Carmen M. Ortiz, who brought the charges against Swartz: she might be a bit of a villain, okay. Information wants to be free, it’s been said. But whether this means free of charge or merely liberated from its confines is a distinction most often left unmade.

What we know so far, if the allegations in the indictment are true: late last year Swartz busted into the MIT network in order to conduct his download in secret, though he has been working at nearby Harvard for many years and has no direct affiliation with MIT. At Harvard, as at pretty much any U.S. university, Swartz would automatically have had full access to JSTOR. It’s been widely asserted that Swartz intended to distribute the material he downloaded from JSTOR to the public, e.g. by posting the lot onto a file-sharing site like The Pirate Bay. And it’s no wonder that people are saying this, because the government’s indictment alleges it directly, but the indictment provides not a single shred of evidence to support these claims.

In a statement released the day the indictment was unsealed, U.S. Attorney Ortiz said: “Stealing is stealing, whether you use a computer command or a crowbar and whether you take documents, data or dollars. It is equally harmful to the victim, whether you sell what you have stolen or give it away.” Stealing may be stealing, but exactly what is the theft here? There were a few tweets around the time of the press release pointing out the absurdity of Ortiz’s remark: “JSTOR is empty!” “I sincerely hope JSTOR will be able to recover the documents that were stolen from them.”

If we want to understand the fix that Aaron Swartz is in, a full understanding of the details is in order. Let’s start with JSTOR. What is it?

JSTOR (for Journal Storage) is a nonprofit organization founded in 1994 by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for the purpose of digitizing and distributing academic journals over the wire. The project was hatched at the University of Michigan with an initial $700,000 grant for hardware and software, plus an extra $1.2 million to pay for scanning just “ten core journals in history and economics” (Hardware, scanning and software development were astronomically expensive in those days.)

Seventeen years on, JSTOR digitizes and distributes over 1,400 journals, mostly to schools and libraries. The journals are divided up into different “collections” (“Arts & Sciences VIII,” for example, offers 140 titles, including a series of rare 19th and 20th-century art magazines). The price for access to these collections varies wildly, according to the size, nature and location of the subscriber. Access is free for any nonprofit institution on the African continent, for example, and in a number of developing countries in other parts of the world. In the U.S., though, it might cost a four-year college over $50,000 for top-tier access; if you teach or study at a participating institution, you can read all the stuff your institution subscribes to for free.

In order to make these documents available, JSTOR has to license the content from publishers. Negotiating these licenses is a tricky business, not least because an academic journal has generally got a backlog of older content that, though it may be in the public domain, will still have to be scanned and archived. Some publishers charge web users outside the institutional subscription system a per-article fee for access to their stuff, a practice that has enraged many, given that quite a lot of this material is in the public domain, and the publisher’s right to paywall such material seems therefore questionable.

A lot of people seem to believe that it doesn’t cost anything to make documents available online, but that is absolutely not so. Yes, you can digitize an academic journal and put it online, but if you mean to offer reliable, permanent availability, it costs a huge amount of money just to keep up with the entropy. Plus you have to index the material to make it searchable, not a small job. Everything has to be backed up. When a hard drive fries, when servers or database software become obsolete or break down, when new anti-virus software is required, all this stuff requires a stable and permanent infrastructure and that does not come cheap. Finally, the more traffic you have, the more it costs to maintain fast, uninterrupted server access; you can see this whenever some little blog is mentioned in a newspaper and its server crashes five seconds later. In the case of JSTOR you are looking at many millions of hits every month, and they can’t afford any mistakes.

So is JSTOR uniformly a good guy? Maybe not; it would certainly be nice if they would make their public-domain materials available to the general public. But if you are an academic librarian, JSTOR, a nonprofit, probably isn’t making your blood boil the way for-profit publishers like NPG (Nature) and Reed Elsevier (The Lancet) do, the latter of which I have seen referred to online as “Lord Voldemort Elsevier” owing to the company’s greed and general rapacity (though at least Lord Voldemort E. finally ordered a halt to the arms fairs traditionally thrown by one of its subsidiary companies, after top brass at The Lancet et al. kept screaming their pointy heads off).

Another thing to consider is that academic writers are paid through salaries and grants; they aren’t paid (not directly, anyway) for the publication of their work. The whole system of compensation for academic content is very different from commercial publishing. When you pay for a JSTOR article online, none of the money goes to the author, it goes to the publisher.

Why Swartz? Why Now?

Once Swartz had been collared, JSTOR declined to pursue charges against him. (Politico reports that MIT plans to press charges, but university officials have not confirmed.) Indeed JSTOR immediately made a public statement to the effect that they have no beef with Swartz. There are two obvious reasons why the Feds decided to pursue criminal charges anyway. The first is that the Feds were already pissed off at Swartz and were just waiting for a chance to go after him.

In 2008, Swartz, taking advantage of a free trial of PACER, a government database of court records, cleverly automated a download of nearly 20 million documents. This was in response to the call of information activist Carl Malamud for donations of downloaded PACER documents, which ordinarily cost eight cents per page. Malamud’s position is that since the public owns these documents, access to them should be easy and free of charge online. In the event, Swartz hadn’t broken any laws, so the Feds were forced to drop their investigation. Perhaps a certain resentment lingered.

The other reason for going after Swartz is that he is a progressive activist and passionate champion of the free Internet and of open access. He has been so outspoken about open access in particular that his 2008 “Guerrilla Open Access Manifesto” was removed from its website, apparently in response to Swartz’s legal troubles. Indeed, it has got some hairy stuff in it, considering the author’s current situation:

We need to take information, wherever it is stored, make our copies and share them with the world. We need to take stuff that’s out of copyright and add it to the archive. We need to buy secret databases and put them on the Web. We need to download scientific journals and upload them to file sharing networks.

On the other hand I could see having left this document online, loud and proud. Because, “stuff that’s out of copyright,” he plainly says. That throws a particular complexion on the matter.

Open Sesame

So what does Open Access mean, exactly? We have several good prototypes already available and thriving, such as the Public Library of Science (PloS), where scientists all over the world have been publishing their papers openly for years, with no fee for access to anyone anywhere on the Internet ever, all published under Creative Commons licenses. Here is a relevant bit from the PLoS website:

In 2003, PLoS launched a nonprofit scientific and medical publishing venture that provides scientists and physicians with high-quality, high-profile journals in which to publish their most important work. Under the open access model, PLoS journals are immediately available online, with no charges for access and no restrictions on subsequent redistribution or use, as long as the author(s) and source are cited, as specified by the Creative Commons Attribution License.

PloS charges those who wish to publish a fee, usually several thousand dollars, to cover peer review and publishing costs. These fees are ordinarily covered by the researcher’s institution.

Keep all that in mind as you read a typical comment recently written by someone who understands bupkes about this thing: one Greg Maxwell, who recently uploaded a 33GB file of JSTOR articles onto The Pirate Bay in protest of the Swartz indictment. (Maxwell says the file contains the whole pre-1923 public domain archive of the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society.)

The documents are part of the shared heritage of all mankind, and are rightfully in the public domain, but they are not available freely. Instead the articles are available at $19 each — for one month’s viewing, by one person, on one computer. It’s a steal. From you.

This is about twenty kinds of not true. JSTOR is paid (not by the public, but by institutions) for a service, not for content. The money that individuals pay for these articles goes not to JSTOR, but to the publisher that is making the material available.

Let’s follow this out a bit. There are nearly 19,000 documents in this 33GB download, and anyone can take them off The Pirate Bay — and then what? It will tax an ordinary home computer quite a lot to search just this one file, the archives of a single journal of the 1,400-plus currently distributed by JSTOR; that’s the tiniest drop in the bucket. The practical futility of Maxwell’s gesture only demonstrates that JSTOR is providing an invaluable service to the public, even with respect to documents in the public domain — one that could be improved upon, maybe, but completely impossible for individuals to duplicate using existing technologies.

But the worst misapprehension in Maxwell’s remarks is his total misunderstanding of what public domain really means. Shakespeare is “part of the shared heritage of all mankind,” too, but does that mean you can march into a Barnes & Noble and take any copy of Shakespeare that you want out of there for free? No! You have to pay Barnes & Noble and Penguin Classics or whomever for making it available to you in a form you can use, in this case a book. To fail to appreciate this point is to weaken the argument for open access by depriving it of clarity and focus.

Consider Project Gutenberg, where someone has kindly volunteered the work of scanning all of Shakespeare into digital form, and still other volunteers have provided text cleanup and money and server space and IT work so that you can download Shakespeare there for “free”, but, well, no, it’s not free; this has cost and is costing someone something, just as public money has been allocated by your local government to pay publishers and librarians to maintain public copies of books that you can borrow. In each case there is work to be done by people who most often need to be paid (and deserve to be paid) for their efforts.

Finally, making a profit off of public domain works is allowed; indeed, it’s half the point. You’re allowed to make a hip-hop rendition of Shakespeare’s sonnets and then sell it to make money. The crux of the matter here is balancing the public interest against private interests; individuals should have the right to be compensated for their work, and the public should be free to reuse and remix the products of our shared culture.

Enter The Lawyers

A lot of open source advocates in the academy are pretty steamed at Aaron Swartz. As Meredith Farkas, the Head of Instructional Services at Portland State University, wrote in an email: “I don’t think that releasing copyrighted works to the public is the best way to make the case for opening up scholarship or promoting open access,” and this appears to be a widely held view. The thing is, we have absolutely NO indication, and no way of knowing, that Swartz meant to do anything of the kind. And just on the face of it, I can’t imagine he did.

It seems far more likely that if he meant to distribute any JSTOR articles on a file-sharing site, he would have stripped out any copyrighted material first (1.7 million of the 4.8 million articles he downloaded, according to the indictment.) That would be child’s play for someone like Swartz to do, and it would certainly have decreased his chances of landing in the soup.

Still, the government’s indictment alleges that he intended to distribute the stuff to the public “through one or more file-sharing sites,” without offering any details as to why they think he was going to do that. If they hope to prove this allegation based solely on the 2008 Guerrilla Open Access Manifesto, it would seem that they have got an uphill climb.

For one thing, Swartz has been working for years on analyzing huge data sets at Harvard and elsewhere. He has a longstanding professional interest in the study of large data sets. Sure, it’s a little bit fishy that he didn’t use the network at his home institution in order to access JSTOR. If the allegations in the indictment are true, it would also appear that Swartz took steps to cover his tracks in order to escape detection. I could think of a zillion possible reasons for this with one lobe tied behind my back: Did Swartz want to keep the nature of his work secret from a colleague for some professional reason? Had the Harvard IT department refused to permit him to take that much data down?

As many have pointed out, JSTOR has got its own systems for performing analysis on its data, but so what? No hacker of Swartz’s abilities would be likely to need or want the kind of help JSTOR could offer him. That would be like telling Ferran Adrià to go to Whole Foods to get stuff for lunch; dude probably will not be coming back with a precooked pizza.

Swartz is being charged with hacker crimes, not copyright-infringement crimes, because he didn’t actually distribute any documents, plus JSTOR didn’t even want him prosecuted. These charges are: Wire Fraud, Computer Fraud, Unlawfully Obtaining Information from a Protected Computer, Recklessly Damaging a Protected Computer, Aiding and Abetting, and Criminal Forfeiture, and Being Too Smart for Being Such a Young Guy, and That Seems Dangerous (I made up only the last bit.)

By far the best analysis of the underlying legal reasoning of the Swartz indictment so far comes from the blog of Max Kennerly, a Philadelphia trial lawyer. Kennerly, too, finds it bizarre that U.S. Attorney Ortiz should be pressing this matter in the absence of any further beef between MIT, JSTOR and Swartz.

I don’t see what societal interest Carmen Ortiz think she’s vindicating with the Swartz indictment. According to Demand Progress, JSTOR already settled their claims with him. What more needs to be done here? The “criminal violation” here arises not from any social duty — like, you know, our society’s communal prohibition on murder — but rather from Swartz “exceeding the authorization” imposed by JSTOR on its servers. Prosecuting Swartz criminally makes less sense than prosecuting telecommunications companies for violating their consumer agreements, and we all know that’s not going to happen any time soon. […] The whole case looks like the iPhone prototype saga again: a civil claim that some overly aggressive prosecutor is trying to dress up as a federal crime.

In order to prove the claim of wire fraud, Kennerly says, Ortiz will have to prove that Swartz meant to defraud JSTOR, which really means “defraud out of money.”

I asked Kennerly about this. If Swartz really intended to make the JSTOR documents available on a file-sharing site as the indictment claims, thereby potentially preventing publishers from getting their JSTOR fees, is it still technically “defrauding” even if no money were ever to change hands? He replied (and this is some dense stuff, but please bear with me and get on in there, because it’s crucial):

That’s a good point you raise, and it could potentially complete the circle to show fraudulent intent. Assuming a jury finds, as a factual matter, that Swartz intended to release the documents, the prosecutors will likely argue that it’s a “fraud” because Swartz was only allowed onto JSTOR’s servers on the condition that he abide by its rules; if his intent was to release the documents to the public, that would break those rules, and so he “defrauded” JSTOR by misrepresenting his intentions when accessing it.

Consider the Skilling v. United States case (PDF) from the Supreme Court last year (yup, Skilling as in the guy from Enron). Scroll to III(A)(1):

Enacted in 1872, the original mail-fraud provision, the predecessor of the modern-day mail- and wire-fraud laws, proscribed, without further elaboration, use of the mails to advance “any scheme or artifice to defraud.” See McNally v. United States, 483 U. S. 350, 356 (1987) . In 1909, Congress amended the statute to prohibit, as it does today, “any scheme or artifice to defraud, or for obtaining money or property by means of false or fraudulent pretenses, representations, or promises.” §1341 (emphasis added); see id., at 357–358. Emphasizing Congress’ disjunctive phrasing, the Courts of Appeals, one after the other, interpreted the term “scheme or artifice to defraud” to include deprivations not only of money or property, but also of intangible rights.

[You can see how the reasoning would be bound to differ a lot, depending on whether or not you were talking about materials already in the public domain.]

In an opinion credited with first presenting the intangible-rights theory, Shushan v. United States, 117 F. 2d 110 (1941), the Fifth Circuit reviewed the mail-fraud prosecution of a public official who allegedly accepted bribes from entrepreneurs in exchange for urging city action beneficial to the bribe payers. “It is not true that because the [city] was to make and did make a saving by the operations there could not have been an intent to defraud,” the Court of Appeals maintained. Id., at 119. “A scheme to get a public contract on more favorable terms than would likely be got otherwise by bribing a public official,” the court observed, “would not only be a plan to commit the crime of bribery, but would also be a scheme to defraud the public.” Id., at 115.

The prosecutor would say the copyrighted articles were both “property” and, if that didn’t work (and I can see it not working) that the copyrights were an “intangible right,” like described above.

If I was Swartz’s lawyer, though, I would turn around and say: the absence of any pecuniary gain for Swartz removes it from “fraud.” The release of those documents is almost certainly copyright infringement, but that’s not the same thing as “fraud.” Consider this further part of the Skilling case:

In 1987, this Court, in McNally v. United States, stopped the development of the intangible-rights doctrine in its tracks. McNally involved a state officer who, in selecting Kentucky’s insurance agent, arranged to procure a share of the agent’s commissions via kickbacks paid to companies the official partially controlled. 483 U. S., at 360. The prosecutor did not charge that, “in the absence of the alleged scheme[,] the Commonwealth would have paid a lower premium or secured better insurance.” Ibid. Instead, the prosecutor maintained that the kickback scheme “defraud[ed] the citizens and government of Kentucky of their right to have the Commonwealth’s affairs conducted honestly.” Id., at 353.

We held that the scheme did not qualify as mail fraud. “Rather than constru[ing] the statute in a manner that leaves its outer boundaries ambiguous and involves the Federal Government in setting standards of disclosure and good government for local and state officials,” we read the statute “as limited in scope to the protection of property rights.” Id. , at 360. “If Congress desires to go further,” we stated, “it must speak more clearly.” Ibid .

If I was Swartz’s lawyer, I’d say we have a McNally issue here. Congress has already spoken on what it means when someone wrongfully distributes someone else’s written works: it’s a copyright infringement. He didn’t deprive anyone of property, he had more copies than they liked. If he intended to distribute them, well, that’s an “intent to infringe on copyright,” which isn’t a crime.

What will the judge do? Beats me. Odds are she or he will send it to a jury to decide on its own what Swartz’s intent really was, and, frankly, I can see them acquitting him as lacking the sort of malicious “mens rea” we think of as criminal. At that point the case would be dead. If they convict him, maybe these issues will go to the appellate courts.

Aaron, I Am Your Father

“An indictment is an allegation,” Harvard law professor Lawrence Lessig wrote in a recent statement regarding the Swartz case published on the Media Freedom website. “[…] It is one side in a dispute.” Lessig, one of the strongest advocates for open access and copyright reform in this country, indeed in the world, has been connected to Swartz for a long time. He brought Swartz on board to design the metadata format for Creative Commons, which Lessig co-founded. Here is how old Aaron Swartz was at that point:

It would not be far off to characterize Lessig as Swartz’s mentor. From the same statement:

I can’t believe Aaron did this for personal gain. Unlike, say, Wall Street (and what were the penalties they suffered?), this wasn’t behavior designed to make the man rich. Nor, if the allegations are true, was this behavior designed to interfere with any of JSTOR’s activity. It wasn’t a denial of service. It wasn’t designed to take any facility down.

What it was is unclear. What the law will say about it is even more unclear. What is not unclear, however, to me at least, is the ethical wrong here. I have endless respect for the genius and insight of this extraordinary kid. I cherish his advice and our friendship. But I am sorry if he indeed crossed this line. It is not a line I believe it right to cross, even if it is a line that needs to be redrawn, by better laws better tuned to the times.

Information activists like Lessig and Carl Malamud have been very vocal in their condemnation of the tendency of academic publishers to keep their materials locked up for the benefit of “elite” institutions like American universities. Lessig gave a rousing April keynote address on this and related topics at CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research (“The Architecture of Access to Scientific Knowledge: Just How Badly We Have Messed This Up”). He was deliberately preaching to the choir, here, in a widely visible forum; it’s an important address, well worth watching. CERN is at the forefront of the open access movement, having adopted in 2005 a specific open access publications policy to encourage the free dissemination of scientific research and information. Physicists generally have spearheaded open access initiatives around the world with spectacular results, including the arXiv open access system for publishing scientific papers here in the U.S.

Still, there was maybe an injudicious statement or two in this speech. At one point Lessig showed a slide of a tweet made by Malamud: “Jstor is so morally offensive. $20 for a six-page article, unless you happen to work at a fancy school.” (Actually no, though, it’s not JSTOR that is making this money, it’s free if you are in a developing country, and so on.) If the Aaron Swartz case clarifies the position of open access advocates with respect to nonprofit services like JSTOR, that at least will be a good thing.

The conclusion of Lessig’s CERN presentation is particularly stirring.

We need to recognize in the academy, I think, an ethical obligation […] An ethical obligation which is at the core of our mission. Our mission is universal access to knowledge — not American university access to knowledge, but universal access to knowledge in every part of the globe.

We don’t need, for our work, exclusivity; and we shouldn’t practice, with our work, exclusivity. And we should name those who do, wrong. Those who do are inconsistent with the ethic of our work.

The aims and ideals of Aaron Swartz can, I believe, be laid to some degree at this man’s door. That is something I would be very proud of, if I were Lawrence Lessig. Whatever the results of the government’s actions against Swartz — and whether or not those actions are ultimately motivated by an instinct toward intellectual property protectionism of the kind demonstrated by the RIAA and others in the U.S. — there can be little doubt that the motives of people like Lawrence Lessig and Aaron Swartz spring from a desire to serve the public good. To that extent we are in their debt, rather than the reverse.

Maria Bustillos is the author of Dorkismo and Act Like A Gentleman, Think Like A Woman.

Top photo by Jacob Appelbaum; photo of Lessig and Swartz by Rich Gibson.

Nicholson Baker's 'House of Holes': Mini-Excerpt #2

Rhumpa was her name, and, yes, she paid a visit to the House of Holes. The people she was staying with in New Haven were wealthy and under-read. Although they were middle-aged, their minds were very young and she couldn’t take them seriously. She saw a pepper grinder in the middle of the table, and while they talked about the price of tires she unscrewed the little knob on the top, and when it came off she lifted the wooden part off the central spindly thing and looked inside, where she could see in the shadows of peppercorns. She thought, The peppercorns are waiting to be ground up. They’re still round, like little dry planets, but not for long.

Rhumpa held the machine to her nose and smelled the distant sharpness of the pepper, which made her smile. And then the pepper grinder got bigger and she jumped down into it and fell through tumbling peppercorns, and she smelled a hundred dinner parties of the past.

Then she was herself again, but standing on the porch outside the House of Holes. She rang the buzzer. A man with a bag on his back answered. He introduced himself; his name was Daggett. He took her into a small room with a round wooden table and, referring to a clipboard, began asking her questions. He asked her to describe her ideal man.

“I like men who are intelligent and witty,” Rhumpa said. “Also kind to animals and interested in other people and able to hold a conversation of reasonable length.”

Daggett frowned and looked at his clipboard. “It says here that you favor a man with a heavy, dark dick. It quotes you as saying, ‘Some nice things are just not possible with a small, pale dick.’”

“Where did you get that piece of information?” Rhumpa asked, outraged.

“During reassembly they do a spectrum analysis,” Daggett said. “They screen for diseases, of course, and comb through for lurid thoughts. What’s your ideal sexual encounter?”

“Oh, touching, kissing, caressing,” Rhumpa said, at a loss.

“It says here that you would favor having three Italian airplane pilots in uniform shoot their comeloads onto your belly while you cup your clitoris with a wooden spoon.”

“They don’t necessarily have to be Italian,” Rhumpa said. “And they can be race-car drivers if that’s easier.”

Nicholson Baker’s House of Holes will be released on August 9th.

And: Previously.

Rick Scott Mocks Jobless

Florida governor Rick Scott’s new initiative is actually, quite literally, one in which he travels the state and takes peoples’ jobs. He is touring about, making doughnuts and delivering newspapers and performing lowly paid labor — basically taunting the jobless. It’s really quite bizarre — as the unemployment numbers in Florida are worse than those in Detroit.