Two Poems By Michele Battiste

by Mark Bibbins, Editor

A Few Words of Appreciation

Thank you for choosing me. Thank

you for choosing to study anatomy, for

differentiating between a fever and a minor

disturbance, a small misunderstanding, a passing

whim. You have a dog and so you can tell

intuitively as well as scientifically. When attention

wanes. When anyone else will do. When a breastbone

is no different from any other breastbone and when

a breastbone will never release you, not until

you’ve gnawed it to shards that scratch your throat

going down.

Thank you for your discretion. Thank

you for the porkpie hat pulled low so no one

can guess which gaze is avoidable. I appreciate

your lack of actualization, your double whiskey

restraint, which is surprising. You’ve not sent

signal, which others may read as disinterest,

but once I had a cat.

Thank you for occasionally sitting

next to me, for the brush of thigh when you shift

away. I snuck my hairclip into your pocket.

It’s cruel to deny the tension, to breathe

casually, to refuse you the rare scent

of encouragement.

Thank you for remembering that I am

not Van Gogh, that none of my body parts

are extraneous, that if I offer you my breast,

the bone is inseparable. And I wouldn’t mind

your teeth on me. If you were so inclined.

Nightcap at Bemelman’s

Lonely isn’t the problem.

The problem is the youth

in the corner wearing white

plastic glasses. He has

lovely bar snacks and I have

no place to sit or to put

my coat. The problem is

it’s my round and the drinks

are seventeen dollars each.

Claudia and Jorg have a

lovely marriage and a live-in

nanny. When I say youth

I mean a man in his late

twenties. I want to curl my

tongue around his earlobe.

Even Jorg can’t get us

a table with bar snacks.

He’s the U.S. president

of some European bank. At

the youth’s table sits a man

in a tuxedo. He might be

Steve Martin. At the bar sits

a woman in a brief black

dress, impersonating. Her

teeth are a poor woman’s

teeth. Claudia rolls her eyes

but Claudia doesn’t

even bother to summer

in the Hamptons. I’ll tell you

a story. My brother in

Daytona at the Boot Hill

Saloon. He flirts. The woman

is drunk. Not attractive. Her

teeth are a poor woman’s

teeth. Her boyfriend, a strangely

polite biker. His leather

vest smells of grape tobacco

and sweat. He asks my brother

nicely, “stop.” My brother clocks

the boyfriend. The problem is

not that the woman wants them

to fight, wants to witness this

strange commerce determining

her worth. The problem is back

at Bemelman’s. Not the youth

who hasn’t bothered. Not Jorg

and Claudia who will find

a place to sit tomorrow

at the next bar. The problem

is the woman at the bar

who has a seat, here, tonight.

Michele Battiste’s work has appeared in Beloit Poetry Journal, Mid-American Review, Women’s Studies Quarterly and Verse Daily. Her first book,

Ink for an Odd Cartography, was published in 2009 by Black Lawrence Press. Her most recent chapbook is Slow the Appetite Down (Spire Press). She lives in Boulder where she teaches and studies and wades in the creek.

There is so much more poetry available right here, in The Poetry Section’s vast archive. You may contact the editor at poems@theawl.com.

Cheap Gas? It Could Happen!

How Michele Bachmann could bring back $2 gas: “Bachmann’s economic policies (such as immediate drastic cuts in federal spending) would surely cause a new recession, the recession would also affect Europe, China, India and other major oil consumers. Oil prices would collapse and gas prices would indeed plummet below $2 a gallon (just as they did in late 2008).”

Chase the Racebow

Ooh, Racialicious just started a four-part panel discussion on interracial dating. I always like when people talk about funny perceptions of race when they were young, like this one: “There were a ton of interracial relationships in my family. For the longest time I assumed my white aunts were just fair-skinned black women.”

Man Eats Healthy

Remember that story about how Bill Clinton once ate an entire baked potato in one bite? Well, he could still do that now, so long as there was no butter or sour cream on it.

Devil Babies!

Man, they look nothing like Looney Tunes led me to believe. Anyway, good luck, Tasmanian Devil babies! I hope you don’t get that thing on your mouth.

Do Not Mess With Tuscan Monks

“A group of Franciscan monks furious at the theft of bibles from their church in Florence have taken the unusual step of praying for the thief to be struck down by diarrhoea…. In a note, pinned up in full view of worshippers, the monks say they hope the thief sees the error of his ways. But in case he does not, they add: ‘We pray to God that the thief is struck by a strong bout of the shits.’”

Land of the Rising Son

“According to the story, he apparently lived to the ripe old age of 106 in Japan, where he was buried in what is now modern-day Shingo. He changed his name to Daitenku Taro Jurai, married a Japanese woman, Miyuki, and had three daughters, according to an English-language pamphlet offered in a small chapel on a forested hill in the village.”

— Take a visit to the town where Jesus Christ, after escaping his crucifixion by boat, lived out the rest of his days.

'Dude Where's My Car?' is 128.1 Months Old Today

Sure, it may be five years since Snakes on a Plane hit theaters. (“Today, yes, it’s hard to imagine Snakes on a Plane being central to anyone’s life,” writes The Atlantic today of the film that one moron at the time called either “Airplane! meets United 93 or Soul Plane meets Turbulence 3: Heavy Metal.”) But today is also another anniversary: it’s been 3898 days since the release of Dude Where’s My Car?

Lest we forget, the pre-meme Dude Where’s My Car? changed American cinema in what are, from our vantage point, increasingly more obvious and important ways, and ways totally unrelated to the Internet. It starred a young Ashton Kutcher (then just 23, and yet to become the editor of Details magazine!) and also Seann William Scott, now 34 and fresh out of rehab. Dude Where’s My Car? was an wildly important experiment in the dumbing-down of American entertainment and a fresh entry in the Hollywood cost analysis game. Made for $13 million, without the fiscal example of DWMC? there would be no lingering Final Destination franchise (also begun in 2000), and then later, no Saw franchise (begun in 2004), no Harold and Kumar (also begun 2004), and, of course, no Snakes on a Plane in 2006. In fact, 2000 was a turning point in the business of movie-making: Scary Movie also first arrived in 2000, forever to be remembered as the year that it was rediscovered that comedy could be made on the cheap (in every sense). Something Leslie Nielsen and friends knew all along, of course, RIP.

Six Authors Who Were Copywriters First

Six Authors Who Were Copywriters First

by Nate Hopper

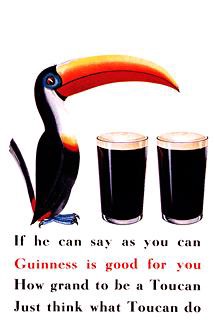

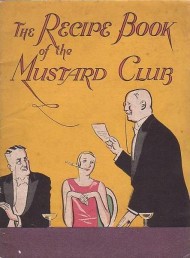

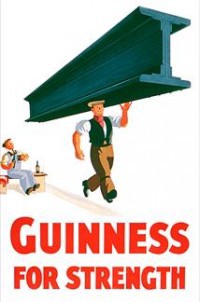

For many writers struggling for publication, advertising has proven a useful field (it does pay, after all): F. Scott Fitzgerald, Salman Rushdie, Dorothy Sayers, Don DeLillo, Joseph Heller and Helen Gurley Brown all worked as copywriters early in their careers — some with more success than others. Rushdie came up with “Naughty. But nice” cream cakes for Ogilvy & Mather; Sayers introduced “Just think what Toucan do” to Guinness and founded a dotty, fictional (and wildly popular) “Mustard Club”; and, thanks to Fitzgerald, streetcars in Iowa once ran with the promise “We keep you clean in Muscatine” sparkling on their sides.

Yet for all six, advertising was mostly just a means to an end — a day job to keep them solvent until they were lucky enough to leave. But their time in advertising wasn’t a waste: as copywriters, some learned how to write economically and on deadline; others discovered fertile subjects in the office life and business culture around them; while others used office hours to work on the books that would later make their names.

F. SCOTT FITZGERALD

In February 1919, a 22-year-old F. Scott Fitzgerald was discharged from the army. He was without a job, but in love with a woman from Alabama named Zelda Sayre who refused to accept his marriage proposals until either a job or money materialized. So Fitzgerald moved to New York City in search of a newspaper position that would help him enter the writing world. In a fascinating 1935 interview with The New York Post, he described making the rounds of the newsrooms with a bundle of his lyrics for the Princeton Triangle Club, a theatre troupe, under his arm: “The office boys were not impressed.” After a slew of rejections, he met a man who told him to skip out on journalism and invited him to come work as a copywriter for an ad agency.

“’It’s perhaps a bit imaginative,’ said the boss, ‘but still it’s plain that there’s a future for you in this business. Pretty soon this office won’t be big enough to hold you.’”

Fitzgerald wrote short stories at night and, during the day, streetcar sign slogans for $35 a week. (Andre Le Vot’s F. Scott Fitzgerald: A Biography mentions that Fitzgerald also wrote lines for billboards — but fails to say if one was ever for a doctor.) “The hit I made with a slogan,” he said in the Post interview, “I wrote for the Muscatine Steam laundry in Muscatine, Iowa — ‘We keep you clean in Muscatine.’ I got a raise for that. ‘It’s perhaps a bit imaginative,’ said the boss, ‘but still it’s plain that there’s a future for you in this business. Pretty soon this office won’t be big enough to hold you.’”

The pay was too meager to fund the lifestyle (and gin) Fitzgerald craved, and he’d soon pinned 122 rejection slips from magazines around his apartment. His distance from Zelda tortured him, too. So after only a few months, he quit copywriting — and New York City.

He later wrote: “I was haunted always by my other life — my drab room in the Bronx, my square foot of the subway, my fixation upon the day’s letter from Alabama — would it come and what would it say? — my shabby suits, my poverty, and love. While my friends were launching decently into life I had muscled my inadequate bark into midstream… I was a failure — mediocre at advertising work and unable to get started as a writer. Hating the city, I got roaring, weeping drunk on my last penny and went home.”

At his parents’ home in St. Paul, Fitzgerald reworked a novel he’d written during the war about a young Princeton student who’d enlisted, expanding the book to include the student’s post-war struggles in New York. It was titled This Side of Paradise, and in March 1920, thanks to some in-house championing by Maxwell Perkins, Charles Scribner’s Sons published it. While the book didn’t net Fitzgerald much money, it popularized his work and allowed him to charge more for his short stories. It also made him suitable for marriage. A day after the first printing sold out — three days after its release — Fitzgerald wrote to Zelda, asking her to meet him in New York City and marry him. She did.

SALMAN RUSHDIE

One day, in 1969, Salman Rushdie ran into a former acquaintance who’d disappeared from the London fringe theatre scene in which Rushdie was active. “He’d bought a sports car, he had a blonde secretary and he was making shampoo commercials with tall thin girls. He also looked like he had put on a considerable amount of weight,” Rushdie said in an entertaining guest speech for a 2008 advertising-awards ceremony. “He said, ‘You should try this, Salman, because it’s really easy.’”

Rushdie went to take a test at the large agency, JW Thompson, where the man worked. “The only question I remember was they asked you to imagine that you met a Martian who mysteriously spoke English and you had to explain to them in less than 100 words how to make toast.” (D.C.R.A. Goonetilleke’s biography mentions that the test also asked for a jingle on the merits of seatbelts.) He failed the test.

Rushdie snagged a copywriting position at a smaller firm but then quit to finish his first novel, The Book of the Pir. But when the book didn’t find a publisher, he began working a couple afternoons a week at then-”relentlessly unfashionable” Ogilvy & Mather, dividing his time between copywriting and writing. “As I look back, I feel a touch of pride at my younger self’s dedication to literature, which gave him the strength of mind to resist the blandishments of the enemies of promise,” he wrote later. “The sirens of ad-land sang sweetly and seductively, but I thought of Odysseus lashing himself to the mast of his ship, and somehow stayed on course.”

Rushdie was not the only aspiring author at the agency, of course, and he describes his colleagues hiding their manuscripts and screenplays in their desks whenever the agency’s head would fly in from New York. His seven years at Ogilvy & Mather were productive. For the Daily Mirror, he came up with, “Look into the Mirror tomorrow — you’ll like what you see.” He also thought up “Naughty. But nice.” for a cream cakes company after watching a bunch of Brit sitcoms (the line’s an allusion to Dick Emery’s “You are awful (but I like you)”). The client initially rejected the concept, but a year later, without Rushdie’s foreknowledge, the tagline was everywhere, including TV:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dlq0196ulmI

There was also “Irresistibubble” for Aero, which remains the candy-bar company’s slogan today. Aero wasn’t Rushdie’s account, but a panicked, blocked coworker asked him to help brainstorm. The coworker was so nervous as they batted around ideas that he was sweaty and stammering. Then, as Rushdie remembered it in that same 2008 speech, the man was on the phone and his stutter kicked in: “Whatever he was asked he said he couldn’t do,” recalled Rushdie. “He said, ‘It’s impossib-ib-ib-ible’, and I thought, ‘Ping!’ It was one of the very few ping moments actually. While he was still on the phone sweating and stammering I wrote down every word I could think of that ended with ‘able’ or ‘ible’ and turned it into ‘bubble’.”

Throughout his time as a copywriter — including a switch to Ayer Barker, where he came up with the tagline, “That’ll do nicely,” for American Express — Rushdie kept writing. While at Ogilvy & Mather, his first published book, Grimus, was released. At Ayer Barker, he wrote his next novel; one morning, he spent a couple office hours deliberating over what to call it, typing “Children of Midnight” and “Midnight’s Children” over and over at his desk before settling on the latter.

Rushdie left copywriting in 1980, the year before Midnight’s Children was published, but never lost the habits he’d formed as a copywriter: “I now write exactly like that. I write like a job. I sit down in the morning and I do it. And I don’t miss deadlines. I do feel that a lot of the professional craft of writing is something I learnt from those years in advertising and I’ll always be grateful for it.”

DOROTHY SAYERS

In a 1922 letter to her parents, Dorothy Sayers wrote, “I’ve no idea whether I shall make anything of this business.” She was in London, in the midst of a month-long trial period at the advertising agency Benson’s. Her letters from this period are filled with fretting over whether she’d get cut from the job, which paid four pounds a week, a salary she needed to supplement earnings from Whose Body?, the first of her Lord Peter Wimsey mysteries.

But Sayers was brought on permanently and landed a raise and an office to herself on the agency’s top floor. She relished the creativity and the word play of the job, notes James Brabazon in his biography. When she went out to pubs with her coworkers she’d wear a lapel badge of the Froth Blowers, the beer drinkers’ union.

Sayers wrote ads for a number of sandwich ingredients, including Sailor Savouries, margarine and mustard. In another letter to her parents, in 1923, she wrote: “Mustard again! It is astonishing that they should want so many advertisements for mustard. However, let’s hope that’s the end of it for a bit.”

It wasn’t, though. The creation of the Mustard Club — one of the most popular ad campaigns of the time — occupied her time for the next few years. Hatched from an inside joke between Sayers and her future husband, journalist Atherton Fleming, the club was described in one ad this way:

The Mustard Club (1926) has been founded under the Presidency of the Baron de Beef, of Porterhouse College, Cambridge. It is a Sporting Club, because its members are always there for the meat. It is a Political Club, because members find that a liberal use of Mustard saves labour in digestion and is conservative of health. It is a Card Club, but Members are only allowed to play for small steaks.

The motto of the Mustard Club is ‘Mustard Makyth Methuselahs,’ because Mustard keeps the digestion young. The Password of the Mustard Club is ‘Pass the Mustard, please!’

While Sayers was never formally acknowledged as the campaign’s chief copywriter, Brabazon observes that the entire campaign had Sayers’ touch: from its fictional characters (Miss Di Gester, the secretary; Lord Bacon of Cookham, among others); to a prospectus that claimed the club had been founded by Aesculapius, the god of medicine; to the recipe book, which included a Shakespeare and Chaucer reference by a “Devilled beef” recipe: “Who sups on a devil should have Mustard in his spoon.” The fictional club grew so popular it issued roughly a half-million real memberships before the war.

The agency’s offices had an iron spiral staircase, and Brabazon describes Sayers descending the stairs, her cloak waving behind her, a cigarette holder in one hand and the other hand in the pocket of a black jacket or holding scribbled concepts. One frequent destination was the office of illustrator John Gilroy, with whom Sayers worked, in 1928, on the famous zoo adds for Guinness. The collection of these ads on the Guinness website says the campaign didn’t debut until the mid-’30s, after Sayers’ tenure at Benson’s; and according to the Guinness Collectors Club, Gilroy continued producing Guinness ads into the ’60s, using the same themes. But Sayers is widely credited for her work on the concept and the original jingle: “If he can say as you can/Guinness is good for you/How grand to be a Toucan/Just think what Toucan do.”

In 1930, Sayers would leave the agency to pursue her writing full-time. By then she’d published five mysteries and a collection of short stories. In 1933, she used her memories of the place to speedily come up with the premise for a mystery in order to hit a deadline (she later hated the book because of how rushed its writing was). The book, Murder Must Advertise, was centered around the mysterious death of a copywriter who falls down an iron spiral staircase. Lord Wimsey, going undercover at the agency to solve the case, finds that he has a surprising knack for copywriting and comes up with a successful campaign for Whifflet cigarettes. Gazing into a mirror one day, Wimsey remarks, “Strange, to think that a whole Whifflets campaign seethes and burgeons behind this solid ivory brow.”

Don DeLillo

Like Rushdie, Don DeLillo worked at Ogilvy & Mather (although in the New York, not the London, offices). But, unlike Rushdie, DeLillo is not to be found giving fond speeches at advertising-awards ceremonies. In a 1991 New York Times interview, DeLillo said he’d only taken a job as a copywriter after he couldn’t turn up one in publishing. After working at the agency for five years, he quit and, as he put it, “embarked on my life, my real life.” But the transition away from writing print ads (he never worked in commercials) wasn’t so he could write, he’d later tell Guernica: “Actually, I quit my job so I could go to the movies on weekday afternoons.”

DeLillo has steadily maintained that “his experience as an advertising writer… explain[s] little in his career,” notes Thomas Pietro in the introduction to his compilation Conversations with Don DeLillo. Yet traces of the experience can be found in his novels. As Mark Osteen, president of the Don DeLillo Society, wrote in an email: “Most of this experience fed into his work — and particularly into his first novel, Americana,” — which DeLillo began writing three years after leaving Ogilvymdash;”in which the character Clinton Bell, is an adman… A lot of what [DeLillo] has to say about it comes in Clinton’s words: for example, that ‘television is an electronic form of packaging.’”

In Americana, Clinton tells his son David, the novel’s protagonist, a story about a shrewd piece of marketing devised by his own father: “McHenry — the Star-Spangled Pajamas,” pajamas with 48 stars sewn on every pair. The product made the company owner rich and Clinton’s father famous. “It was the greatest merchandising gimmick of the decade,” says Clinton before concluding, “You could afford to be innocent in the days.”

In another scene, David asks his father, “Why is it that all advertising people I’ve ever known want to get out? They all want to build their own schooners, plank by plank, and sail to the Tasman Sea. I know a copywriter at Creighton Insko Dale. At lunch one day he started to cry.”

JOSEPH HELLER

In 1953, Joseph Heller was working as a copywriter for the Merrill Anderson Company in New York. One night, as he later described it to The Paris Review, “this line came to me: ‘It was love at first sight. The first time he saw the chaplain, Someone fell madly in love with him.’” As he remembered in his autobiography Now and Then, he sat down at his desk that day and wrote an entire chapter longhand.

Two years later, the chapter, entitled, “Catch-18,” was published in New World Writing (in the same issue, a chapter from Kerouac’s On the Road was published under the pseudonym Jean-Louis). Heller made $25. By then he’d left the agency and a couple other jobs and was working as an advertising-promotion copywriter at Time. In his new biography of Heller, Just One Catch, Tracy Daugherty recounts how Heller once successfully wooed the Simmons mattress company to buy ad space in Time by using an image of the Red Queen from an old edition of Through the Looking Glass and the quote, “Now, here, you see, it takes all the running you can do to keep in the same place!” in a presentation — a success that got him his first raise.

Another two years passed and the chapter had become a halfway-finished novel with a publishing contract. Another four years, during which Heller moved to McCall’s as a promotions manager, and the book was finished and released under the new title: Catch 22. Another two years and the novel was the bestselling paperback of the year, selling over two million copies; but only earning its author $.03-$.04 a copy, by Heller’s own math. (That’s about half a million in today’s dollars.)

It wasn’t until a year-and-a-half later, when the movie rights were sold for $100,000 (that’d be about seven times that today), that Heller left the advertising world.

HELEN GURLEY BROWN

Helen Gurley Brown was 31 and an agency secretary when she won a 1953 Glamour magazine competition to share the title of “Girl with Taste.” The victory brought her a trip to Hawaii, minor celebrity status and, eventually, a shot at a promotion to copywriter. Although it’s not clear that a career in copywriting was even Brown’s true goal — what she really wanted was to win the contest. “I felt I better not say I just want to be a secretary, that wasn’t what they were looking for, so I said ‘I’d like to write copy,’” she later recalled. But then, as Jennifer Scanlon recounts in Bad Girls Go Everywhere, a staffer from Glamour called up Brown’s boss and asked him why he hadn’t given her the opportunity to write copy, his wife seconded the question and Brown got her chance.

“[W]hen your mirror has been telling you for years that the most extravagant adjective that can ever apply to you is…attractive. Poof to that! Tonight you will be beautiful!”

Brown ferried back and forth between her secretarial desk and her copywriting desk for three years. Apparently, her boss found it hard to replace her (he’d later say that was the real reason he hadn’t promoted her earlier). The agency was Foote, Cone & Belding, and while there Brown wrote lines for Sunkist, Catalina swimsuits, Breast-O’-Chicken tuna and Lockheed, among other accounts.

But her flair for writing copy that appealed to women garnered such high demand that another agency successfully lured Brown away with an offer of twice the money. For Max Factor eye makeup, she wrote: “It’s nice to be an angel most of the time — but tonight — let your eyes reveal the daredevil side of you! Let them go deep, dark and devilish…suggesting, just suggesting the wanton and wicked.” For Max Factor’s Pan-Cake line: “Tonight you must be more beautiful than you really are… you must be beautiful, period, when your mirror has been telling you for years that the most extravagant adjective that can ever apply to you is…attractive. Poof to that! Tonight you will be beautiful!” Within a decade Brown was the highest paid copywriter on the West Coast and had won several awards for her work.

Throughout her time working as a copywriter, she sent in advice articles for women to Glamour, Playboy, and Esquire, without success. But then came the bestselling Sex and the Single Girl in 1962, and Brown said “Poof to that!” to the ad world when she took over as editor-in-chief of Cosmopolitan three years later.

Nate Hopper is a summer Awl reporter.

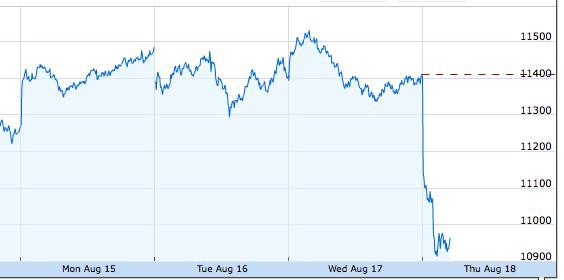

"Give Us Money or We'll Shoot This Dow"

Before the hilarious Morgan Stanley report — which says that we’re “hovering dangerously close to a recession” and then says that “policy errors” have to do with their vote of no confidence in the U.S. markets, by which they mean “make us and/or give us much more money” and/or “don’t cut government spending” — came the Goldman Sachs report, which put forward the idea of the U.S. economy being a plane, a plane that can stall, just like a real plane, if GDP growth is below 2%. One of their top two concerns? “US fiscal tightening.” (In the end, just FYI, they put the possibility of a “new” recession at 1 in 3.) Basically we are in a weird position where, for maybe the first time, Republican talking points (if not actual Republican beliefs or actions) threaten Wall Street, which has, over the past few years, gotten everything it’s wanted from the White House. (And will continue to do so, not that there’s anything left to give.)

The funny thing in all this is that the ideas behind these economics are all, sure, made up. For instance, it’s an largely agreed-upon principle, though I don’t think necessarily a correct one, that if you gave everyone in America $1000 as a “stimulus,” that it would be a real disaster. (Some would hoard; some would waste; some would pay down debt: and these mixed results would, overall, be “bad” for the economy.) Yet bank analysts also think that curbing government spending is a mistake… when really, much of what the government does is hoard, waste and pay down debt. And what do corporations do with direct “stimulus” moneys? Same thing, pretty much! They sure don’t create jobs, we found out. The government doesn’t do so well at that either. In the end, we’d be better off distributing actual money in actual human hands. At least half of it would get paid directly to big corporations anyway. (Like Citibank! And Visa!)