Nuclear Disaster Is Not The Only Thing To Worry About

Anxious about the possibility of a Fukushima-style nuclear calamity in the event of another earthquake here on the East Coast? You should be! But save some shelf space in your cabinet of concerns for our deteriorating dams:

In 2009 the American Society of Civil Engineers released a survey of the state of infrastructure in the U.S. The group found that dams are, on average, in terrible disrepair. Of the more than 85,000 dams, more than 4,000 are unsafe or deficient, and nearly 1,800 of those are located where a breach would cause severe damage to life or property. With so many dams, it is hard to know where the gravest danger lies. The average budget for dam inspectors is distressingly low. For instance, Texas employs just seven inspectors to keep an eye on 7,400 dams, and in many states inspectors lack the authority to inspect private dams, including those built to hold back the chemical by-products of mining operations. A report by Switzerland’s Paul Scherrer Institute estimates that dams are the most potentially hazardous source of energy. A catastrophe at an average dam has the potential to kill 11,000 people. The second-most-hazardous energy source? Nuclear.

Uh oh. I don’t know about you, but I think it’s way past time for desperate measures to resolve this issue. Only collective action can ensure that we properly address this critical problem. I propose that we all put our fingers in our ears, shut our eyes and repeat, “Nothing’s gonna happen, it’ll be fine” over and over. I mean, it’s kept us safe so far, right?

Murder, Suicide And Mayhem In Brooklyn Heights (Yes, Brooklyn Heights!)

Murder, Suicide And Mayhem In Brooklyn Heights (Yes, Brooklyn Heights!)

Very little happens in Brooklyn Heights. During Truman Capote’s years here, his friends would enquire, “But what do you do over there?” It was a fair question — and an eternal one. Mine wonder the same thing. One pleasure of America’s first suburb is that it is, to an extent unusual in an ever-churning city, impervious to change — economically, structurally, but also in a more fundamental sense: The question, Did anything happen in the Heights today? can almost always be answered with Not much. The news is blessedly mundane: Either a pet is missing or the street’s been sullied by a fallen tree or pothole.

If the Heights seems like a neighborhood out of time, that is to some extent by design. Its landmark status, bestowed by Mayor Wagner’s Landmarks Preservation Commission in 1965, limited new structures to the height of a four-story row house and ensured the Heights would always look a bit like “Sesame Street,” whose creators lived in — and, legend has it, drew inspiration from — the neighborhood. Population growth has been flat to slightly negative for a decade; turnover on Montague Street is confined to a new bank and another new bank; and the hipness factor is, if anything, negative as well.

There are rumors that t’was not always thus. My neighbor, a lovely, rascally George Carlin doppelgänger, insists the Hotel St. George was ground zero for orgies in the ’70s. If you believe Bob Dylan, Montague was once home to “music in the cafés at night/And revolution in the air.” (We still have a cafe. It’s called Tazza and the coffee is okay.) But by the time young Barack Obama moved here in the early ’80s, any wild stories he might have heard about the place were outdated. It’s been a quiet place for a long time.

That’s not to say, however, that a cloud of violence and brutality never descended on the Heights. It has, albeit in a small way. No neighborhood is immune to a deadly drizzle every now and then, and mine has had its share, particularly in the early years before it was absorbed into the greater New York leviathan. While the Heights couldn’t be confused with the Five Points — “chippies” and their “maudlin songs” were the big problem of 1893, says The New York Times — it saw a respectable amount of murder, mayhem and even a prize fight. Here are some of the stories that rocked the dailies then.

A Shooting On Christmas Day

On December 25, 1877, Mr. Charles E. Johnson attempted to kill his wife Florence at his father-in-law’s 43 Monroe home. The incident, reported the Brooklyn Eagle, “has produced more excitement in society and police circles than any tragic affair which has occurred in some time.” Florence and the Manhattan-born Johnson, barely 20 years old and baby-faced, wed only a year earlier in a ceremony presided over by Reverend Henry Ward Beecher. The wedding, said The New York Times, “attracted much attention among the people of fashion in both cities by reason of the high social standing and wealth of the contracting parties.”

Charles and Florence had been married only a few months before he turned ill-tempered and verbally abusive. Nine months into the marriage Florence gave birth to a beautiful child. Life with Charles continued to be unendurable (he remained ceaselessly unpleasant), so she packed up and moved, child in tow, into her father’s home. Once apart from her husband, Florence, observed the Eagle, “regained her lovely spirits.” On Christmas Day, the poor woman (for reasons unknown) invited her father-in-law over to explain why she had left his son. Charles showed up in his stead, and shot his wife — as she held their baby — above the right breast with a five-chamber Smith & Wesson revolver. En route to the police station, Charles was apologetic. “I didn’t intend to shoot her,” he told the officer. “I merely wanted to frighten her.”

The shooting caught the neighborhood by surprise. From the Eagle: “[H]e would be the last one in the world who would reasonably be suspected of being capable of figuring as principal in the shooting business.”

Six months later, Charles, who had been charged with attempted murder, was declared insane on the basis of his wife’s testimony in which she disclosed that her husband had once before threatened her with a pistol. The doctors disagreed on whether he had epilepsy or dementia, but each believed Charles to be “thoroughly insane.”

Sibling Suicides

On February 5, 1893, Miss Sallie Coop of 144 Montague was found on the third floor of her home in what the Eagle described as “a state of semi-consciousness.” There was a pistol by her side; around her was the smell of chloroform; and her bed robes were covered in blood.

Sallie left no note, but it was said the marriage of her twin sister Elizabeth to George Perry Fisk — at which she was the maid of honor — “preyed upon her mind.” The ceremony had taken place a week before her death. At the reception, noted the Times, “Miss Sallie seemed to be one of the very happiest in the company.” Even so, Sallie was frequently melancholy and her periods of depression had gotten progressively worse.

Seven years later, Sallie’s brother Herman, suffering from financial losses and a failed love affair, shot himself in the head while standing on their father’s grave in Greenwood Cemetery.

He was buried near his sister in lot 12868, section 4.

A Hungry Child

How it was that Mamie Holland, 10, went from the Home for Destitute Children to a grave in Potter’s Field in the span of weeks was a matter of contention at her funeral on Monday, June 6, 1887.

The child’s deterioration was rapid: Three weeks prior, Mrs. C.F. Martin brought Mamie to her boarding house at 93 Pineapple on the condition that the girl would act as a nurse to Mrs. Donahue, a boarder. She became ill the first night. Mrs. Donahue endeavored to return Mamie to the Home, but was overruled by Mrs. Martin after the girl begged to stay.

Mamie’s health showed no improvement. Dr. W.H. Bates examined her and found that she was half-starved. Mamie told the doctor that the Home, where she had lived for five years, was to blame. “She told me several stories about the way she had been treated at the home, and if her stories were true the children there are certainly poorly fed.” Mrs. Martin told The New York Times that Mamie “hardly knew what meat was.” An autopsy confirmed the cause of death as rheumatism of the heart.

Stories of mistreatment of the Home’s charges were denied by Matron Battie, who produced several children to the Times for inspection. The reporter confirmed they did indeed appear healthy.

Taking Aim At The Landlady

Did James T. Walker intend to kill his landlady? Well, the landlady herself, a Mrs. Barbara A. Davidson of 14 Willow, said it was all a misunderstanding. The story, as told by the officer on the scene, Roundsman McCarty: Shortly after 7 p.m. on January 29, 1880, he was summoned by Mrs. Davidson’s nephew, who he had heard a gun fired in the boardinghouse. The roundsman entered the house, confronted Walker and found two pistols in his pocket. Walker, visibly drunk, was asked why he shot at Mrs. Davidson. “That’s my business,” he answered. “She has ruined me, and I will kill her yet.”

Walker’s non-denial was confirmed by Mrs. Davidson, who told Captain Crafts of the Second Precinct that Walker had indeed tried to kill her.

The next morning, Walker strode into court. According to a gimlet-eyed reporter for the Times, his blond mustache was “waxed and twisted in a way that bespoke a regard for his personal appearance amounting almost to foppishness.” The prisoner “did not seem to be much concerned by the predicament in which he found himself.” Mrs. Davidson, whom the paper tartly deemed “not specially attractive,” testified that Walker followed her into her room on the parlor floor, grabbed her shoulder, and said, “What does this mean?” as he fired two shots over her shoulder. As Mrs. Davidson hastily left the room she heard a third shot, which, she supposed, was Walker’s feigned attempt at suicide.

Judge Walsh: What would he do it for?

Mrs. Davidson: Oh, I don’t know; I suppose he was jealous.

Judge Walsh: Jealous — about what?

Mrs. Davidson: Oh, I couldn’t tell you, I’m sure.

Mrs. Davidson’s hesitation wasn’t surprising. She had not been honest with the police, neglecting to mention that she had of late attracted the attentions of a former boarder, a young commission merchant named Harry Ferris. Both parties were married to other people, so this was awkward. The police believed that, on the day in question, Ferris had visited Mrs. Davidson in order to pay the balance of his bill. Walker, they said, probably discovered the two together, assumed the worst and that is when the shooting started.

The Hoop-Skirt Fire

At a little past 4 on Friday, March 15, 1861, a fire broke out on the fifth floor of 106 Orange, home to the American Hoop-Skirt Company. Susan A. Wilson, daughter of the building’s janitor, and Ann B. Tranahor, a seamstress, were killed.

Engine Company No. 3 found Ann “nearly suffocated.” She was taken to City Hospital where, reported The New York Times, “[s]he vomited quite freely, and having received no other injury than that caused by inhaling smoke, strong hopes are entertained that she will recover.” Ann was visited in the hospital by her brother-in-law, Theodore Questoff, a Paymaster’s Clerk in the US Navy. She expected to die and a day or two later, she did.

Susan, who not only worked at 106 but lived in the basement, jumped from a window and fell approximately 60 feet to the concrete pavement. She was pronounced dead within five minutes of her discovery. The police surgeon claimed she had not broken a single bone.

In the weeks that followed, George Albrecht, the company foreman, was subject to an inquest. There was no evidence pointing to his guilt and a jury did not find him responsible. As quoted by the Times:

“That the deceased came to her death by precipitating herself from the rear window of the fifth-story of No. 106 Orange-street [sic] causing a fracture of the spinal column, and exonerating George Albrecht from all blame.” Signed, Duncan Richmond, Asher Williams, Wm. Little, Abner Terwelliger, Peter Walters, A.H. Campbell.

Three months later, 106 Orange was lit up again, this time with a fire on the fourth floor. It was, said the Times, “presumed that the fire was set by some malicious person.” There were neither fatalities nor injuries.

Boxing In The Living Room

On the night of March 2, 1887, Patrick Fitzgerald and James Larkins, notorious pugilists both, needed a place to break each other’s faces.

The first stop for the fighters, officials, reporters and a dozen paid spectators was the Pastime Clubhouse House in Manhattan at 66th Street on the East River. They expected it would be empty; it wasn’t. A trip to Long Island was proposed, but the idea so disgusted the spectators that most of them left. Then a butler, who happened to be a pal of Fitzgerald, suggested that they might head across the river. His employers lived in Brooklyn Heights and they were away. He reasoned that their dining room would be an excellent place to have the match; so long, as the Eagle put it the next day, spectators could “restrain their enthusiasm sufficiently to prevent the neighborhood from being alarmed.”

The crowd, reduced by then to the timekeepers, the seconds, reporters and the fighters, walked across the Brooklyn Bridge — the construction of which had been completed four years before. By the time they got to the Heights it was past midnight and the neighborhood was quiet as a crypt. The crowd entered the house and prepared the place for the fight: the furniture was removed and overcoats, dresses and “ladies wraps” were put on the floor to “deaden the noise.”

The fight began at 3:40 a.m. The terms:

• Five hundred-dollar purse, funded by “100 sporting men of New York, Jersey City and Brooklyn”

• Four-ounce gloves

• Fight to the finish

Larkins was 5’7″ and weighed 120 pounds. Fitzgerald was 5’4″ and 117. Both men were considered to be in excellent condition.

The first two rounds were deemed even, each man “fighting fiercely and taking punishment gamely.” In the third round both were knocked down with Larkins getting the edge. He was knocked into the fireplace in the fourth round but made Fitzgerald bleed in the fifth. Fitzgerald broke a small bone in his right arm but kept fighting. As the 12th round commenced a non-fight-related noise was heard. The butler, who one suspects may have at that point had a guilty conscience, left to investigate.

It was The Boss. “Thomas,” he was heard yelling, “is that a dance party you are giving?” The butler attempted to explain what was going on, but the master of the house tossed him aside and entered the dining room. For what happened next it’s worth quoting the Eagle scribbler in full:

He saw two men, whose bodies were bare to the waist, banging each other all over his dining room with comparatively bare hands. Their faces were puffed and bleeding, and they seemed tired, but their ferocity and determination was far from being exhausted. A baker’s dozen of spectators cheered them on.

The homeowner blanched and threatened to call the police. It was only then the crowd realized he had returned home. A few suggested tying him up, but that proved unnecessary. Once he agreed to “a vow of secrecy,” the crowd agreed to leave. It was decided that the fight was a draw, so Larkins and Fitzgerald would split the purse.

Elon Green writes supply-sider agitprop for ThinkProgress and Alternet.

Photo from the Robert N. Dennis collection of stereoscopic views, New York Public Library.

Big Bird Has Grudge Against God, Geese

“God may have made ‘all creatures great and small’ but one leading churchman admitted yesterday he had been left traumatised by Britain’s biggest bird of prey after it attacked him and killed one of his geese.”

Women Sleep, Complain More Than Men

“Women, on the whole, get more sleep and fall asleep faster than men. About 30% of women said they sleep eight hours or more on weekdays, compared with 22% of men, according to the National Sleep Foundation’s 2005 Sleep in America Poll, which surveyed 1,506 people. A small study looking at the sleep of healthy young adults found that women slept an average of 7 hours, 43 minutes in a night, or 19 minutes more than men. And women took 9.3 minutes on average to fall asleep, whereas men took 23.2 minutes…. Given this, researchers say it isn’t clear why in numerous studies women tend to complain more about their sleep, saying they don’t get enough shut-eye and find it difficult to fall asleep and stay asleep.”

Too Soon, Angry Birds Rio

by A Proud American

From time to time, The Awl offers its space to everyday citizens with something to say.

Each 9/11 season, we see more and more the creeping influence of foreign nationals on this important American day of unity and remembrance. Last year they tried to turn Ground Zero into an international house of sharia worship. A few years back, a Polish-born architect named Daniel Libeskind was nearly allowed to turn Ground Zero into a series of hippie-hammocks and cuddle-puddle chambers. And now, this tenth anniversary — the most important to date, because we love round numbers and because we prefer a base ten system of numbering — is also, already, the most cruelly plundered for profit and agenda. I refer of course to the latest update to the popular game “Angry Birds: Rio.”

This “game” was made by Rovio, creators of the original “Angry Birds,” a group of former students from Helsinki that are now funded in part by Palo Alto-based Accel Partners. According to Wikipedia, “Angry Birds Rio initially includes two chapters, each with 30 levels; the Angry Birds rescue caged exotic birds in the first and fifth chapters and attack evil marmosets in the second, third and fourth chapters.” In its latest update, its chapter-and-game numbering system at last included a 9/11 level, which these Finnish japes decided to decorate with an airplane that your birds, so angry at these marmosets et al, must destroy.

How long will America stand for being the butt of Europe’s offensive jokes? As long as Obama allows it to happen, that’s how long. Anyway don’t get me started on the new Porsche 911.

A Proud American will no longer play Finnish-designed mobile games.

How A Bunch Of People With Twitter Accounts Reacted To The Earthquake

Since everything that happens must now microblogged within seconds of — if not actually during — its occurence, let’s take a look at how The Great East Coast Shakefest of 2011 was covered on Twitter.

Some chose to tie the news to current events:

I think Chris Christie just jumped into the raceless than a minute ago via TweetDeck

Alex Pareene

pareene

Apparently, now that Nick Ashford is dead, the earth is no longer solid as a rock.less than a minute ago via web

Erik Tanouye

toyns

THIS IS WHAT HAPPENS WHEN WILL AND JADA ALLEGEDLY BREAK UP ACCORDING TO OK MAGAZINE.less than a minute ago via web

David Cho

davidcho

Some saw the opportunity for pop culture/new media/techonology references:

Pitchfork gives this earthquake a 5.8.less than a minute ago via TweetDeck

grayson currin

currincy

OH: “Well, it’s official: Silicon Valley’s got nothing on New York City now.”less than a minute ago via Twitter for iPhone

Matt Langer

mattlanger

i hope the world doesn’t end before I use all these groupons #nycearthquakeless than a minute ago via TweetDeck

Brokelyn

Brokelyn

There was culinary humor:

New York earthquakes are better because of our thinner crust.less than a minute ago via Twitter for Mac

Joel Johnson

joeljohnson

Naturally, the West Coast couldn’t wait to tell us how jaded and blase they are about geological disturbances:

From the endlessly shaky West Coast to hyperventilating Easterners: stop whining about #quake. It’s like discovering sex for the 1st time.less than a minute ago via Twitter for BlackBerry®

PhilBronstein

PhilBronstein

Hey Angeleno friends, I just heard that some New Yorkers evacuated their buildings! hahahahahahahahahahahahahahahahaaaaaaaaaaaless than a minute ago via Brizzly

ericspiegelman

ericspiegelman

And, perhaps inevitably, some got meta about Twitter:

That was just like the old days, when the ‘49ers immediately wrote down their funniest earthquake quips and gave them to carrier pigeons.less than a minute ago via web

Ross Luippold

rossluippold

And that’s how it happened. I’m a little disappointed in all of you. Except Pareene. Chris Christie fat jokes are gold, I tell ya. Gold!

Ken Auletta Dominates Alec Baldwin in East Hampton

by “David Shapiro”

On Saturday morning, me and Angelica and a reporter drive my mom’s car from Brooklyn out to East Hampton for the 63rd Annual Artists vs. Writers charity softball game, which takes place in a public park next to a really upscale Hamptons strip mall. My only pre-game exposure to the game was when I went to the game’s official website, where I was greeted by an unexpected embedded auto-play video of Mike Lupica speaking really loudly about the game, with a resolution too big for the frame that the video is inside so a lot of the text is cut off. The video sounds like a commercial off a local TV sports network that plays high school games. My only previous exposure to Mike Lupica was in the episode of “Seinfeld” when Costanza is asked who his favorite writer is and he responds, “I like Mike Lupica?” Mike Lupica is a sportswriter for the New York Daily News.

On the drive to the Hamptons, Angelica is talking about the rich history of art in the Hamptons, including the time that Jackson Pollock wrapped his Oldsmobile around a tree, and I am thinking about how if my mom knew I was going to an Artists vs. Writers softball game today she would say, “That’s [conceptually] rich, David,” and also I am wondering what the inverse of this game would be, maybe like an NBA vs. NFL charity villanelle contest or MLB vs. NHL charity contemporary art exhibition?

So I park the car in the parking lot of the strip mall, keep the windows half-open because it’s like 89 and I don’t want to get back into a sweltering car and also nobody is going to reach through the windows and steal out of your car at a luxury strip mall in the Hamptons, and then we walk into the park and see the field, which has hundreds of fans in fold-up chairs crowded around it. About 70 artists and writers are in the fifth inning of their softball game.

Mort Zuckerman, the billionaire publisher of the Daily News (and editor-in-chief of U.S. News and World Report) is pitching for Writers, underhanded, but if you had to guess how he was pitching from the determined look on his face, you would probably guess he was pitching overhand. Perhaps due to Mort Zuckerman’s fierce pitching, the Writers are winning (8–4 I think?) and the Artists look like they’re starting to get worried. I walk to a spot behind the backstop to get a better view and notice that James Lipton, host of “Inside the Actor’s Studio,” is sitting at a folding table and announcing the game with two other announcers. Behind the center field wall there is a maybe 20-foot-tall plastic blow-up bottle of Snapple, I guess because Snapple is sponsoring the game. It makes me suspect that the players are aiming for it and think about how satisfying it would be if one of them popped it with a softball (not as an act of anti-corporate aggression but more as a testament to their strength and masculinity). I am standing a few feet behind James Lipton and he’s wearing a sun-faded fishing vest over his t-shirt.

Then Angelica, who is not a sports fan, comes up behind me and tells me she is going to go to the strip mall to maybe find some water, and I give her a thumbs up and don’t turn around because Alec Baldwin is up for the Artists and I don’t want to miss his at-bat. Here is a picture of Alec Baldwin hitting a pop fly to left field that will be caught in the air, thus retiring the side.

It is really hot in the direct sunlight so I find a spot in the shade and towel off my forehead with the bottom of my shirt and watch the crowd for a minute, mostly families, and when I come back to my spot behind the backstop and next to James Lipton, sportswriter Mike Lupica is being driven in from third base and as he comes down the third base line towards home plate, the entire Writers team comes out of their dugout (actually just the grass next to the third-base line) and high-fives Mike Lupica as he’s on his way to home plate. Mike Lupica high-fives everyone vigorously as he again lives out a dream he has also vicariously been living out through the pages of the Daily News for decades, scoring a run in front of legions of fans, and then Angelica comes back from the mall and gives me some water and shows me a yoga shirt that she bought. Alec Baldwin’s 28-year-old girlfriend is Angelica’s yoga instructor, and she’s probably around here somewhere, and Angelica wants to say hi to her, so she wanders off again, and when I turn back around to refocus on the game, some guy is asking James Lipton to autograph his copy of Dan’s Papers, which is a local Hamptons newspaper. James Lipton obliges.

Back in the Writers dugout, Ken Auletta, prolific author and media columnist for The New Yorker and the man who popularized the term “information superhighway,” who is captain of Writers, is carrying a clipboard and cheering his team on.

So as players come up to bat, I Google them so I can learn about their literary and artistic achievements. I learn that Greg Bello, of Artists, played a minor part in The Wrestler and was also in Requiem for a Dream. Rick Leventhal, of Writers, is a Fox News correspondent. Jim Leyritz, also of Writers, was actually on the Yankees during their 90s dynasty run but I guess has done some sports writing since? Either that or Captain Auletta just wanted to shore up his squad with an ex-Yankee. I also notice that, strangely, both teams have filled out their ranks with some reputable Manhattan cardiologists and other non-literary/artistic professionals who I suspect are the doctors, lawyers, and other professionals who count the celebrities here as clients. Like right now Alec Baldwin is in his dugout conferring with Artists teammate Ron Noy, an orthopedic surgeon whose office is located on Madison Avenue between 48th and 49th Streets and who has some glowing Google reviews, and it makes me think that the eligibility rules are pretty lax and next year some twentysomething Internet writers should stage a coup, join the team, and lead the Writers to victory. When I was younger I was really obese so they made me play catcher in Little League, even though it was murder on the knees, but I think I could reprise that in the 64th annual Artists vs. Writers charity baseball game if anybody who organizes the game, like Ken Auletta for example, is reading this right now: Pitchforkreviewsreviews at gmail dot com.

So anyway, now it is the eighth inning and an Artist who is wearing a jersey that doesn’t have his name on it comes up to bat, and James Lipton announces his name and credentials, which I can’t really hear, and then the batter momentarily interrupts the flow of the game to walk behind the catcher and inform James Lipton that he is an Academy Award Nominee. The game resumes and the Academy Award Nominee gets on base and then is eventually driven in as a run, and he slides head first into home plate, which is maybe an offensive maneuver that violates the two-hand-touch-equivalent spirit of this charity softball game, but nobody on Artists objects because they are desperately in need of runs.

Orthopedist Ron Noy again confers with Alec Baldwin and then it is Alec Baldwin’s turn to bat, and as Alec Baldwin gets up to the plate, he points his bat in the air towards the left field fence, which nobody is paying attention to because the Artists’ squad is congratulating the artist Eddie McCarthy because he hit a home run and drove the Academy Award Nominee in.

So Alec Baldwin calls his shot into left field, Babe Ruth style, and this is Alec Baldwin’s big moment because it is the Artists’ chance to solidify the momentum shift in their direction. But then Alec Baldwin grounds out to the shortstop and unceremoniously walks back into the dugout and is greeted by his attentive teammate, orthopedic surgeon Ron Noy, and it makes me wonder if Ron Noy is Alec Baldwin’s orthopedist and he has recently done some orthopedic work on Alec Baldwin and wants to check in with Alec Baldwin about the new configuration of his body, or if Ron Noy wants to talk to Alec Baldwin because Alec Baldwin seems like a cool guy who anybody would want to pal around with.

The side changes again and soon Jim Leyritz, the former Yankees slugger, is on deck. Jim Leyritz is the only player on either team to perch his sunglasses on top of the brim of his cap, like Major League-style. Jim Leyritz takes more practice swings than any other player in this game, and he scans the field purposefully, because I guess he has more face to lose than anybody else playing in this game because he used to be a professional baseball player and should be showing everyone else here how it’s done. It occurs to me that Jim Leyritz playing for Writers is like if the NFL recruited Terence Koh for the contemporary art squad. That would be a real “special team”! Zing!

Jim Leyritz gets up to bat and watches two softball pitches float by him, which causes one of the other announcers (who is not James Lipton) to announce that it has been six years since anyone walked in the Artists vs. Writers charity softball game, maybe subtly joking that Jim Leyritz is taking this too seriously and should just swing the bat because softballs are huge and they move through the air very slowly.

Jim Leyritz nervously but jokingly asks the announcers how long it’s been since someone struck out, and the announcer doesn’t have an answer, and then Jim Leyritz hits a pop fly to deep center field that is caught, but it doesn’t matter because the Writers are winning by a lot of runs and therefore not relying on Jim Leyritz’s production. He trots back to his dugout and makes a comment in a self-deprecating tone that I can hear but not understand.

During the last inning of the game, it seems like the Writers really have this in the bag so I walk over to the concession stand to buy a t-shirt before the game ends and then everyone will want a t-shirt and they will probably run out of shirts in my size. So I get one in maroon, the Writers team color, not because I am a frontrunner but because I identify with the writers, and I hand the elderly man behind the concession stand money and he hands me back my t-shirt and also the dimebag that I keep my pills in that accidentally got caught inside the $20 bill I handed him (inside my pocket), and he looks at me sternly and says, “Here are your pills,” which sounds vaguely accusatory because he has probably watched some “60 Minutes” segments about prescription drug abuse among young people, and obviously the pills being in a dimebag isn’t helping. This is embarrassing and I want to tell him that I am prescribed those pills and I only carry them around in a dimebag because carrying a pill bottle in my pocket is too bulky and the dime bag secures the pills just as well, but he probably wouldn’t believe me or care, so I just take my dimebag of pills and my t-shirt and walk back behind the dugout and watch the end of the game. Alec Baldwin, in his dugout, yells, “One out! One out!” and then someone else (maybe Dr. Noy?) says something to him and he quietly asks, “How many outs?” and then the other person corrects him and he says, fatalistically, “Two outs,” because the Artists’ chance of a comeback was brighter when he thought there was only one out.

Then the last out is made and the game ends and everyone (fans and players) crowds onto the field, except Alec Baldwin who quietly slips out behind the left field fence with his girlfriend because he would get mobbed. I find Angelica and The Reporter and then The Reporter interviews Ken Auletta and I stand near him, which is where I am standing now: next to the pitcher’s mound of a baseball field in the Hamptons on a scorching Saturday, standing like nine feet from Ken Auletta, Literary Lion and Captain of the Writers Softball team. The Reporter is conducting a post-game interview with him now and I notice he has a spectacular set of teeth, and Angelica says they are definitely veneers but I am willing to give his teeth the benefit of the doubt. His dentist was probably in the game and might be listening to us now. Then The Reporter finishes interviewing Ken Auletta and Ken Auletta introduces himself, probably because I am lurking, and I congratulate Ken Auletta on his win and say, “You guys totally dominated,” and he thanks me and then I ask, “What was your greatest on-field moment?” Ken Auletta looks at me and laughs and says, “You mean when I was about 30 years younger?” I smile and say, “I mean lifetime,” but then Ken Auletta smiles again and mostly ignores the question and tells me that as Captain of the Writers, “This is a game where you try and win, entertain the fans, and get everybody in the game. I have a roster of 40 people,” and then he shows me his clipboard with all of the Writers names on it.

This sounds like a humble/admirable sentiment but honestly, from where I was standing, Ken Auletta ran a ruthless program, stacking his team with a billionaire pitcher (who except Michael Bloomberg, Rupert Murdoch, or someone with a professional death wish would have the courage to hit a homer off a Mort Zuckerman pitch?), a recent ex-Yankee, and a determined sportswriter among other sluggers, while the stars of the other team were a sitcom star and a man who may or may not be his orthopedist. The Writers ended up winning 11–5, making Ken Auletta’s false modesty even more transparent, and I want to ask him if he already pre-ordered opening day tickets to Moneyball or if he pulled some strings and watched a friends and family screening at the director’s house, but he would probably say he doesn’t even know what I’m talking about.

Then Ken Auletta invites The Reporter and Angelica and me to a bar for a post-game drink with the teams, and The Reporter still needs to interview people, so we get back into my mom’s car and drive to the bar. Me and Angelica eat chips in the parking lot of the bank next to the bar, and the guy who was in The Wrestler and Requiem for a Dream walks past us but doesn’t see us eating. Then we go inside and I wash my face in the bathroom and towel off with some very thick but disposable cotton paper towels, probably the thickest possible paper towel you could get before they’re no longer considered disposable, and I am happy to be in probably one of the only places on earth where a group of writers is really rich and has emerged victorious from an athletic contest.

Sent via BlackBerry

David “Shapiro” is 23 and lives in New York City and has a Tumblr.

Something Something Earthquake

Here is what we know now about the magnitude 5.8 earthquake that shook the foundations of New York City (and, I guess, some other places): Although I was forced to walk down (and then back up) four flights of stairs during the evacuation, I am for the most part fine. My ice coffee is a little warm now, but other than that — and the unwanted exercise — I want America to rest assured that I, national treasure Alex Balk, survived unscathed. As you were.

Sad People Never Forget

“Sad people are apparently better than happy people at face recognition, an upside to being down in the dumps that is yielding insights into how mood can affect the brain.”

— Yeah, some upside. “You’re miserable, but at least you will remember the faces of everyone who has made you want to die.” Pass, thanks.

Case History Of A Wikipedia Page: Nabokov's 'Lolita'

by Emily Morris

Wikipedia has an article on almost every subject — including, it turns out, one on how to write “the perfect Wikipedia article.” The guidelines run through a list of the attributes such an article would have — e.g., “[i]s precise and explicit,” “[i]s well-documented,” “[i]s engaging” — before ending on a cautionary note: The perfect Wikipedia article is, by virtue of the collaborative editing process that creates it, “not attainable”: “Editing may bring an article closer to perfection, but ultimately, perfection means different things to different editors.” And as editors pursue perfection, they also must keep in mind another essential quality of a good Wikipedia entry: neutrality. That is, no matter how controversial a topic, an article must present “competing views on controversies logically and fairly, and pointing out all sides without favoring particular viewpoints.”

As a member of the Arbitration Committee, Ira Matetsky settles the kinds of editorial disputes that controversial articles tend to incite. In a series of thoughtful guest posts on The Volokh Conspiracy, Matetsky explained some of the mechanics behind the editorial process. He noted that, generally, while “articles on non-contentious topics are usually accurate; articles on highly contentious articles are usually accurate on basic facts, but can be subject to bias and dispute with respect to the matters in controversy.” As a way of investigating Matetsky’s point (and with Wikipedia editathons making news (sub. req.)), we thought we’d chart the history of a single Wiki entry by using that nifty “View History” button. And what’s a page that’s constantly being edited, has as its subject a work of art with an, ahem, unconventional sense of morality, and is therefore constantly subjected to the editing whims of people with strong opinions, moral or otherwise? She goes by many names, but on my greasy MacBook Pro screen, she is always “Lolita.”

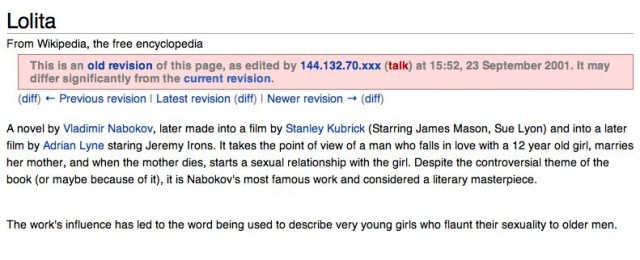

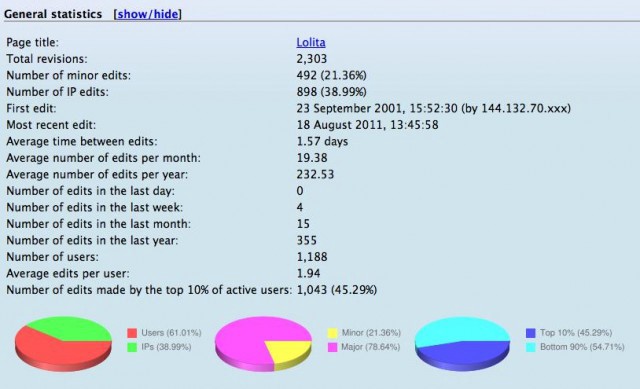

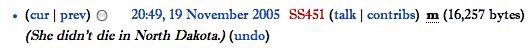

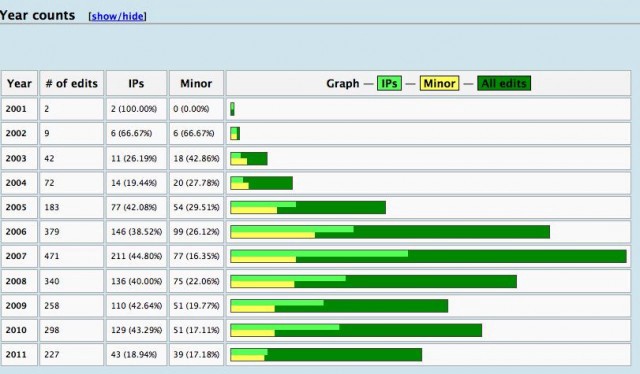

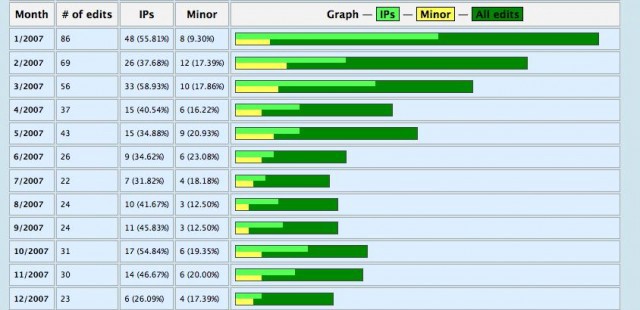

Since 2001, the Wikipedia entry on Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita has been edited 2,303 times. It’s a popular entry, too: of approximately 750,000 Wiki articles out there, it ranks at 2,075 in traffic.

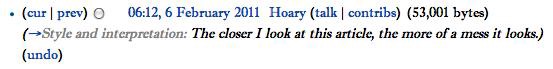

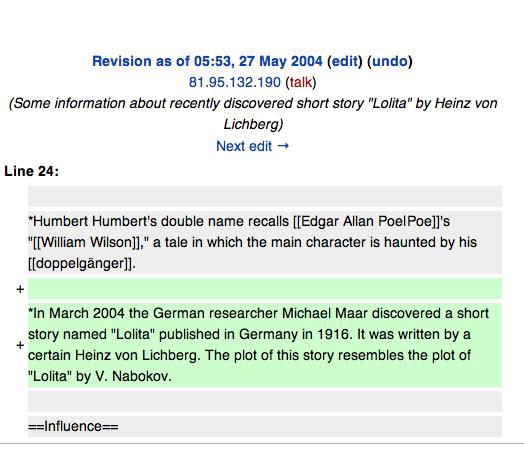

In the past ten years, the entry has grown from the four-sentence description, shown above, to the detailed, 6,000-plus-word monolith of today. The two Lolita films now have their own pages, while the entry on the novel has expanded to include sections on such subjects as Lolita’s Russian translation and its literary allusions. An edit is made, on average, about every other day.

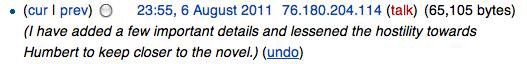

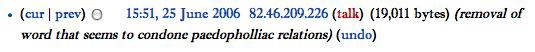

A sift through those 2,303 edits turns up three reasons that users alter the Lolita Wikipedia page: technicalities, new information and debate.

TECHNICALITIES AND MINUTIAE

Par for the course for any article. These details matter to nitpickers, without whom Wikipedia wouldn’t be nearly as reliable.

NEW INFORMATION

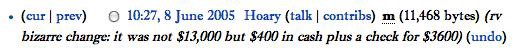

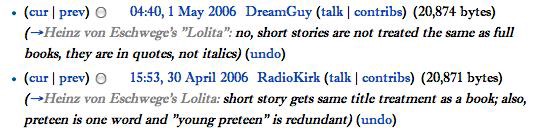

Updated information on other classics may be scarce, but Lolita’s provenance has been in the news in recent years. In March 2004, German professor Michael Maar’s discovered of a 1916 short story by Heinz von Lichberg, also called “Lolita” and containing a very similar plot to Nabokov’s version. The news of Maar’s discovery did not appear on the page until May 2004.

After Maar’s book came out in October 2005, the idea of “cryptomnesia,” that is, “when a forgotten memory returns without it being recognized as such by the subject, who believes it is something new and original,” was added as a possible reason for the similarities between Nabokov’s and von Lichberg’s respective “Lolitas.”

Jonathan Lethem’s February 2007 Harper’s article called “The Ecstasy of Influence: A Plagiarism” briefly mentions Maar’s discovery, which may account for the Lolita page’s highest number of views in January of the same year.

DEBATE

Here’s where the arguments start, and where the tenet of neutrality gets challenged. Over the years, editors have disagreed over what terms to use to describe Humbert Humbert, Lolita and the relationship between them. After all, how do you transform sentences such as this into neutral prose?: “There my beauty lay down on her stomach, showing me, showing the thousand eyes wide open in my eyed blood, her slightly raised shoulder blades, and the bloom along the incurvation of her spine, and the swellings of her tense narrow nates, clothed in black, and the seaside of her schoolgirl thighs.”

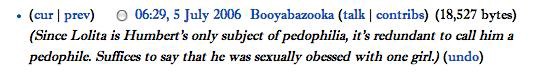

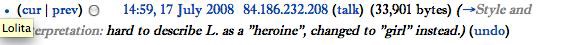

On calling Humbert Humbert a “pedophile”:

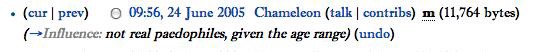

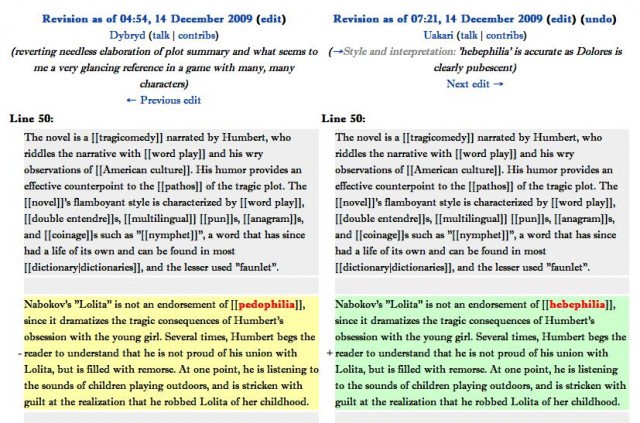

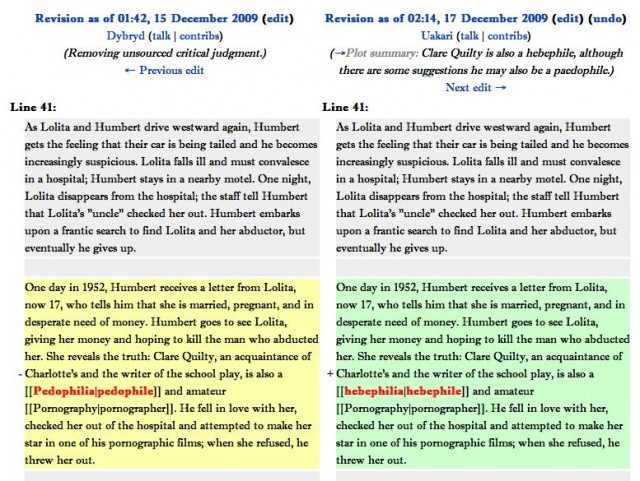

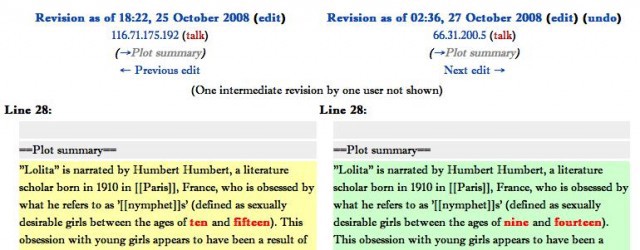

On “pedophile” vs. “(h)ephebophile,” and distinguishing the two. These edits went back and forth over the course of December 14–17, 2009:

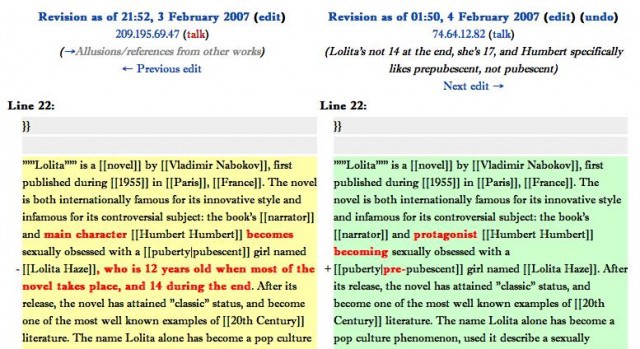

On whether to judge him for it:

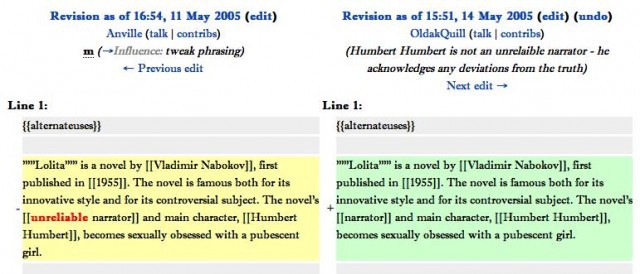

On whether the nature of their relationship makes Humbert Humbert a reliable narrator or not:

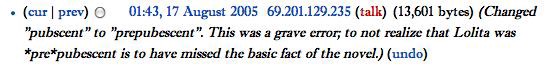

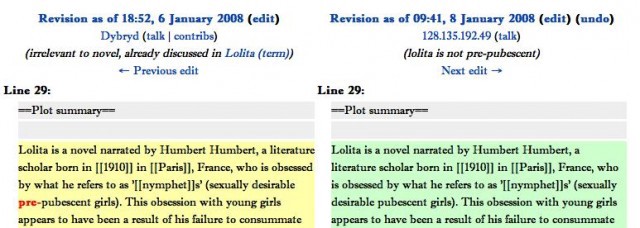

One of the most consistent debates is over the use of “pre-pubescent” versus “pubescent” in describing Lolita’s age.

Note: Merriam-Webster defines puberty as “the condition of being or the period of becoming first capable of reproducing sexually marked by maturing of the genital organs, development of secondary sex characteristics, and in the human and in higher primates by the first occurrence of menstruation in the female.” Or, as Humbert Humbert himself reports: “The median age of pubescence for girls has been found to be thirteen years and nine months in New York and Chicago. The age varies for individuals from ten, or earlier, to seventeen.”

This isn’t Humbert’s first circling of the topic. Earlier in the novel he says:

Between the age limits of nine and fourteen there occur maidens who… I propose to designate as “nymphets. It will be marked that I substitute time terms for spatial ones. In fact, I would have the reader see “nine” and “fourteen” as the boundaries — the mirrory beaches and rosy rocks — of an enchanted island haunted by those nymphets of mine and surrounded by a vast, misty sea.

Dude’s a pedophile. A poetic one.

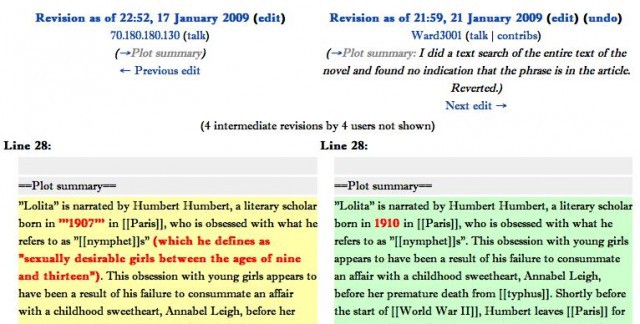

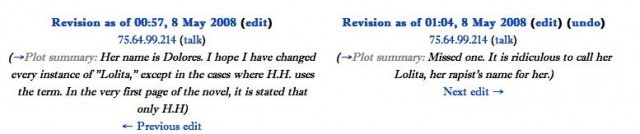

On Lolita’s name, and whether to call her a “heroine” or not.

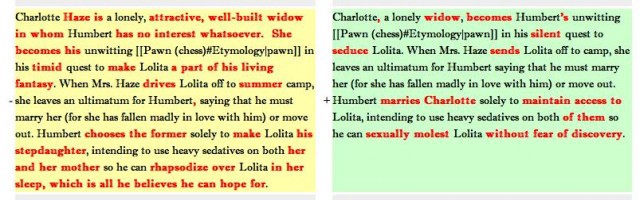

The constant back-and-forth over word choice is just a microcosm of the same (albeit slightly less charged) issue of relaying the plot. This revision from January 2007 changes “rhapsodize over Lolita in her sleep” to “sexually molest Lolita without fear of discovery.”

Entries such as the one on Lolita demonstrate why perfection on Wikipedia remains an “unattainable” goal — when the topic is contentious, perfection will always butt heads against “is completely neutral and unbiased.” One man’s undeniable literary masterpiece is another man’s abominable pedophilic trash, and they’re both editors on Wikipedia. The edits to the Lolita page (and any Wikipedia page) can seem tedious and petty, and many of them are. But the users’ vigilance in keeping some words and changing others, and debating over content and style, does have a purpose: it keeps critical thinking alive and well. The writing, editing, rewriting and re-editing process of a Wikipedia page creates a new entity — the Lolita Wikipedia page, which is not Nabokov’s Lolita, but a work in its own right. In the collaborative editing process, any reader can use the Lolita page to challenge its meaning. In fact, he can reach right in and edit it himself, until someone else edits it again.

Emily Morris is a summer Awl reporter.