Good Intention, "Red Rain"

These short days are the longest.

This is great. Now go home.

New York City, January 17, 2017

★ A blue mist became a grayer drizzle as the morning brightened in reverse. The drizzle became rain, and at lunchtime it was heavy enough to make the pavement shine with headlights as if it were night. Rain bounced off the lid of the coffee cup, and the parka was sheeted with water. It continued through the end of daylight, less than a downpour but more than tolerable. A puddle of vomit on the subway stairs was gradually being diluted into its constituent lumps.

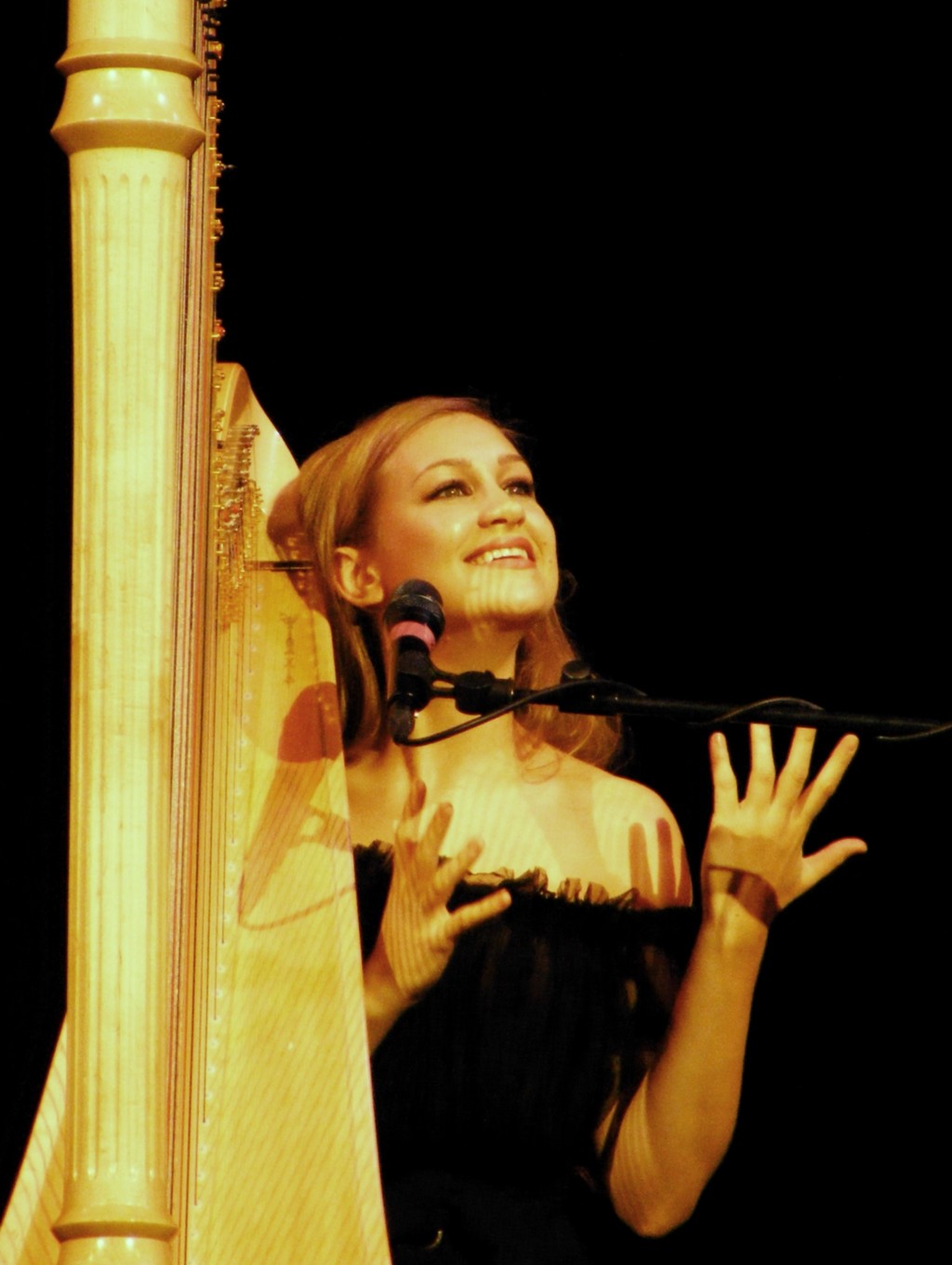

The Book of Right-On

Willow Smith + Joanna Newsom

My favorite thing about Willow Smith’s music career is how extracurricular it is. She had that one meme-y single about whipping her hair, but now that we’re a few years out from its prevalence its success seems like more like a happy side effect than a business decision. In my imagination, Willow said, “Mom, dad, I want to record a song,” and her parents obliged the same way you let your kid order something adventurous off of the menu even though you suspect they’ll be disappointed it’s not chicken fingers—it’s good to grow. But what that single taught us (and what Willow maybe already knew) is that Willow is powerful. She knocked it out of the park, and America was ready to watch her win.

She’s a high schooler, though, and like her brother she’s not totally sold on celebrity. After a few years of relative hiatus, she quietly released an album of self-produced, self-recorded songs in late 2015—Ardipithecus—and they were way different than the first single had been. It was a collection of moody, confessional Tumblrcore songs about gender and growing up and her favorite “Adventure Time” character, and while it didn’t get the same attention as the music she’d released when she was younger, it banged in a promising new way. There’s something very riot grrrl and DIY about imagining the daughter of two major celebrities, who has previously landed a Nicki Minaj feature, eschewing ShOwBiZ to collaborate with her stepbrother on songs that feel produced in a bedroom. Even if they weren’t recorded there, spiritually, it’s like they were.

Anyway, I bring all of this up because Smith posted a video of her covering Joanna Newsom’s “The Book of Right-On” on Instagram this week, and like her LP before it, it’s magical in a way that’s tough to describe but easy to observe:

See what I’m talking about? Good stuff.

The Only Thing You Need To Bring To The Women's March

An alternative shopping list

If you’re living in America right now, chances are you’ve heard of the Women’s March on Washington or one of the 370 sister marches that are taking place across the country this Saturday.

Over at The Cut, they ran a list called “Every Single Thing You Need to Bring to the Women’s March,” and here are the items they suggest protesters consider investing in before they take to the streets:

Uniqlo Heat Tech Turtleneck, $19 at Uniqlo, American Apparel Bodysuit, $49 at American Apparel, The North Face Zip Neck Base Layer, $60 at The North Face… Sorel Boots, $100 at Avenue 32, Hunter Boots, $89 at Nordstrom Rack, Timberland Boots, $109 at Urban Outifitters… Vbiger Touch Screen Gloves, $13 at Amazon, Warmen Faux Leather Gloves, $9.99 at Amazon, Timberland Gloves, $9.99 at Amazon… Patagonia Baclava, $35 at Patagonia, Carhartt Hat, $9.99 at Amazon, Metog Ear Warmers, $8.99 at Amazon… Sof Sole Insoles, $16 at Amazon, Hunter Insoles, $25 at Nordstrom, Miscly Gel Insoles, $14 at Amazon… Romastory Velvet Leggings, $11 at Amazon, The North Face Tights, $50 at The North Face, Uniqlo Heat Teach Leggings, $19 at Uniqlo… Mophie Case, $50 at Amazon, Skyroam Hot Spot, $99 at Amazon, Anker Astro Portable Charger, $15 at Amazon… American Apparel Scarf, $29 at American Apparel, Allegra K Scarf, $8 at Amazon, Uniqlo Heat Tech Scarf, $19 at Uniqlo… Uniqlo Heat Tech Socks, $9 at Uniqlo, Heat Holders Socks, $15 at Amazon… Retro Rewind Sunglasses, $9 at Amazon, Smith Sunglasses, $129 at REI… Grabber Hand Warmer 10 Pack, $11 at Amazon, Chapstick Original 3 Pack, $6 at Amazon, Purell Hand Sanitizer, $15 at Amazon… Thinx Boy Shorts, $39 at Thinx, Depends Slim Silhouette, $39 at Walgreens

As an alternative, I’d like to offer a more pared-down list of requirements for attendees to consider. In order to march this Saturday, you need:

- to want to be there

That’s all.

The Taste of Wings to Come

The historical ironies of Western bug-eating trends

This past holiday season, the startup Six Foods sent out an ad blast inviting their existing consumers and writers alike to spice up their festive parties with their Chocolate Chirp Cricket Cookies. Their messaging played up the novelty of such a product — “feeding crickets to friends usually receives an interesting reaction,” read one solicitation. But the truth is, cricket products aren’t that special anymore. From mealworm spreads to scorpion-laced chocolates or from cricket energy bars to bread mixes to Six Food’s own two-year-established Chirp Chips, American shoppers today have their choice of well publicized and easily obtainable buggy foods.

Entomophagy, or insect eating, exploded in the West over the past half-decade thanks to a series of well-publicized studies by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization and talks by scientists. Bugs like crickets and mealworms, the experts said, contain as much protein as animal meats — and often more nutrients — but with less fat. And they can (arguably) be produced with less feed or fewer greenhouse emissions. Scores of startups responded to these reports, backed by big names like the rapper Nas or tech age self-help guru Tim Ferriss. By 2014, entomophagy was already a $20 million industry. By 2015, multiple industry consultancies were forecasting it as a top emerging food trend, and it’s likely to keep growing.

For all the attention it receives today, there’s one element of insect eating in the modern West that often gets ignored — a tragic irony. Many early reports and the companies they inspired shore up their pro-bug agenda by noting how common entomophagy is in the wider world and throughout human history. But they fail to acknowledge that in almost every society with an insect-eating tradition, the practice is on the wane, largely due to Western cultural pressures to modernize.

It’s near impossible to know how widespread entomophagy was at its historical height. But based on the facts that there’re between 1,000 and 2,000 documented edible insects spread all across the globe (albeit out of over six million total) and that cultures today averse to the practice have some records of it (like seventeenth-century Germans devouring fried silkworms) it’s likely that at some point most (if not all) societies ate bugs. Tropical regions, where diversity and availability are higher, may have even depended on them for nutrition, while in other areas they’d been primarily scarcity or delicacy foods. But entomophagy is a universal of human history.

As of 2005, UNFAO reports count about two billion people within 3,000 ethnic groups, spread across four-fifths of all the world’s nations, who still eat insects as delicacies or common foods. However according to David Gracer, an early and well-known Western entomophagy advocate, many mid-2000s reports citing these figures also noted (in asides) a consistent drop-off in the practice, especially in more traditional bug-eating heartlands like Africa and Southeast Asia.

Some have suggested that entomophagy naturally declines as traditional cultures develop widespread and effective agriculture. Sedentary agriculture, the theory goes, not only provides a much less work-intensive source of protein than wild insect harvesting, but it also turns bugs from an ally into an enemy, ready to threaten a more stable source of food in the fields. But this theory falls apart when one considers the prevalence of insect eating in agriculturally intensive regions from Mali, where people working in or on their way to their crop fields historically picked up any grasshoppers they found as a snack, to Japan, where rural folk long incorporated various larvae or even wasp-studded rice crackers into snacking menus, well into the modern era.

The only convincing explanation for entomophagy’s rapid decline is the joint influence of Western culture and modernization. On the most mechanical level, the more developed a civilization becomes, the harder it becomes to harvest insects — whether due to the proliferation of pesticides or urbanization and the attendant loss of insect habitats. Both forces mean anyone interested in eating bugs would have to go further to find them than they used to and that future generations will have a harder time developing a taste for them. Development and urbanization doesn’t have to spell an end to entomophagy, though. Case-in-point, per Arnold van Huis of the Netherlands’ University of Wageningen, some bugs — commonly various grasshopper species — still thrive and can be harvested in cities. And entomophagy is actually growing in the ever more urban Thailand, where insect farming in fields or in city homes remains popular and profitable — but demand remains so high that locals actually have to import bugs from Cambodia to meet it.

More than habitat loss or pesticide usage or urbanization, the bane of entomophagy around the world has been the West’s aggressive proselytization over the past two centuries of its own phobias and hang-ups around insects. By the eighteenth century entomophagy in Europe was almost entirely unheard of (though it was never huge to begin with). When explorers encountered it in the wider world, some scholars tried to revitalize the tradition in the West as a practical food source — see Rene Antoine Ferchault de Reaumur’s Memoires pour server a l’Histoire des Insectes in 1737, Foucher d’Obsonville’s Philosophic Essays on the Manners of Various Foreign Animals in 1784, and V.M. Holt’s Why Not Eat Insects? in 1885. But most just read it as a savage and unsanitary behavior, eventually looping entomophagy into a fashionable nineteenth-century cultural Darwinism as a sign of primitivism to be shaken off to progress culturally.

This led well into the twentieth century (and in some places even today) to active ridicule and bigotry, exemplified in Harvard entomologist Charles Brues’s endnote on entomophagy in his 1946 Insects, Food, and Ecology: “We may return to this as it serves royally to bolster up the feeling of race superiority, Nordic or otherwise.” The effectiveness of ridicule is reflected quite openly in accounts of encounters with traditionally insect-eating Native American groups in the southwest in the nineteenth and early twentieth century. According to Brues, Native peoples would try to hide their entomophagy from researchers because, “the recent influx of wide-eyed and hilariously mirthful tourists [had] made the Indians bashful.”

Early twentieth-century Jesuit missionaries in California noted that, despite the express mention of entomophagy in the Bible (e.g. locust eating or, according to some views, the manna of the Sinai desert, which may have been insect excretions), they actively taught that insects were dirty and that insect eating could be a cause of civilizational ruination. Often these teachings flew in the face of local dietary needs; some have argued that they led to chronic malnutrition throughout the developing world due to inherited cultural hang-ups.

When those ridiculing you and preaching are in a position of political, military, and relatedly cultural dominance, Gracer points out, there’s a strong incentive to dissimulate towards them: “The people in traditional societies who were first adopters of new ways consistently benefitted by it in terms of agency, in terms of advantages,” he says. Those who abandoned entomophagy stood a better chance at success under Western rule, and served as examples for their peers.

Modern Westerners like to think we’ve moved far past such explicit cultural chauvinism. But the practice of exoticizing and ridiculing entomophagy is alive and well, as Rene Redzepi of the renowned Copenhagen restaurant Noma recalled after he started working with ants about a half-decade ago: “I felt the animosity toward people who eat insects, the Western self-righteousness. As if it cannot be good because people from ‘lesser societies’ eat these things.” (Gracer adds that it’s still very common for people to consume insect dishes unwittingly, love them, and then react with anger and disgust when confronted with the reality of the ingredients.)

Not only have negative attitudes towards entomophagy persisted, animal meat has become a symbol of status for upwardly mobile folks in the developing world. The development of accessible communications technology has fueled the spread of Western TV and movies, news (with its insect dread stories), and other cultural symbols to the farthest reaches of the earth. Their proliferation seems to map onto the widely observed drop off of entomophagy from Benin to Botswana to Japan to South Africa and beyond in the space of just ten, twenty, or thirty years.

“I doubt that I would be willing to eat the same snack again,” wrote New York-based Korean-American painter Kira Greene in 2011 of her childhood spent eating silkworms, exemplifying this cultural force, “now that my thoroughly Western education (including nightmarish visions of Kafka’s Metamorphosis) have instilled an incurable case of entomophobia.”

Often outright rejection and ridicule for entomophagy rather than just a passive neglect for old traditions mark the shift. An account in Hugh Raffels’s 2010 Insectopedia of a visit to an insect museum in Japan includes a note on children, likely just one or two generations removed from a domestic history of entomophagy, mocking displays on Thai insect eating as primitive and stupid. (No one’s entirely sure how Thailand escaped the wave of anti-entomophagy and instead ran in the opposite direction. Gracer thinks it probably has something to do with the fact that their late, beloved king promoted the tradition heavily during a famine in the 1970s, building up a strong, modern insect-farming infrastructure — think warehouses or rough tents packed with crates, each packed and stacked with simple insect habitats, like cut-up egg cartons crawling with grasshoppers — and inculcating a sense of local pride.)

Given the historical basis for this widespread rejection of entomophagy, there is a tragic irony to the growing trend in the West. The local Australian tradition of eating wichetty grubs nearly died out due to European judgment, but now lives on in large part as a draw for Western tourists, and accounts of ancient Southeast Asian entomophagy are now used to sell haute cricket bars. There appears to be no recognition of this irony in Western entomophagy start-up materials.

“That level of metacognition is simply unreasonable to expect, especially from Americans,” said Gracer, who adds that he also sees many, but not all, modern entomophagy entrepreneurs as fairly blind to this. He does believe a few truly want to revive entomophagy worldwide, even if they want to do so more to save the earth than to right a detrimental historical cultural slight.

Much of the recent, trendy Western entomophagy, with its disengagement from this history, is just another slap in the face to insect eating cultures around the world — rejection followed by an about-face turning discarded traditions into the new it. That’s the ultimate cultural hegemon-slash-Mean Girl move. On an utterly practical level, a failure to address this global decline invalidates the earth-saving rhetoric of these organizations — slowly building up the fashionability of entomophagy in the West means almost nothing if the practice in the wider world continues to collapse. From a historically moral and ecologically practical standpoint, entrepreneurs should be using their physical and social capital to spread a new message of insect acceptance through the world — and could do that by working explicitly towards creating sourcing markets for a diverse array of insects from traditional insect-eating societies.

Showing the West’s desire for insects — and transformation of them into chic, modernity-compliant forms like bars, biscuits, and flours — while creating a market to make innovation, tradition, and natural conservation pay worldwide could go a long ways towards repairing the damage of years of snobbery and truly advancing a culinary tradition with gobs of potential. At the very least, it would show historical and global contextual self-awareness — something that’s been lacking in the gung-ho, uncomplicated utopian futurism of trendy Western entomophagy thus far.

Soundscan Surprises, Week of 1/12

Back-catalog sales numbers of note from Nielsen SoundScan.

The definition of “back catalog” is: “at least 18 months old, have fallen below №100 on the Billboard 200 and do not have an active single on our radio.”

Jackie Evancho, whose name you only know because the only fact about her is that she’s performing at Trump’s Inauguration, has made it onto the Top 200 of the back catalog, selling exactly one thousand copies last week. Here are some more facts: one thousand is exactly half of the number of the year in which she was born, she is sixteen years old, and is from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Anyway, I hope she writes Donald Trump a nice thank you note for the record sales.

U2 is going on The Joshua Tree Tour 2017 this year to celebrate the fact that it’s been roughly two Jackie Evanchos since that album was released, which explains its presence in the number one slot with a measly four thousand and some copies. January is rough you guys! Somehow Pentatonix is still selling Christmas records, which makes me really think they might have made a deal with Russian hackers or something. George Michael is still dead, and Tupac got a boost of his Greatest Hits after the announcement of a release date for the biopic, All Eyez On Me. The movie will be in theaters on June 16, what would have been the late Shakur’s forty-sixth birthday. Finally, last week, Aaliyah’s Ultimate finally hit iTunes—the singer was twenty-two years old when she died in a plane crash one Jackie Evancho ago.

1. U2 JOSHUA TREE 4,196 copies

4. TUPAC GREATEST HITS 3,978 copies

21. WHAM! MAKE IT BIG 2,397 copies

59. PENTATONIX THAT’S CHRISTMAS TO ME 1,475 copies

75. DR. DRE CHRONIC 1,327 copies

127. MICHAEL*GEORGE OLDER 1,014 copies

132. EVANCHO*JACKIE AWAKENING 1,000 copies

139. AALIYAH ULTIMATE 978 copies

(Previously.)

William Onyeabor, 1946-2017

And now he’s dead.

“William Onyeabor, the Nigerian synth funk pioneer, died in his sleep on Monday, the Luaka Bop label has announced…. Onyeabor launched his music career in the 1970s, when he put together an impressive home studio and pressing plant in Enugu. Between ’77-’85, he single-handedly recorded, pressed, and printed a series of groundbreaking synth-funk albums. They included classic songs such as ‘Good Name’ and ‘Fantastic Man,’ novel takes on synthesizer-driven funk that stood out even within Nigeria’s thriving music scene.”

The Pitchfork post quoted above has a good selection of videos. The Luaka Bop announcement is here.

New York City, January 16, 2017

★★★★★ The white-streaked sky was bright and expansive. The light projecting up the avenue, over the nuggets of salt still strewn there, had a warm yellow cast to it. Here and there undriven cars held onto their thin snow crusts. The playground handball court still had ice down in the joints of the concrete. Little flat chunks of it broke and scattered as the five-year-old ran around with his tennis racket. The bright fresh tennis ball gathered wet spots and smudges, and damp shoe prints peppered the zone where he set up to return the ball off the wall. The footing was fine, though, and there was no danger of frostbite, no matter how long things might last.

Gidge, "Lit"

What are you like, outside?

Have you been outside today? Don’t do that again. Have you not been outside yet? Stay where you are. If you would like an approximation of current climatic conditions please press play. Enjoy, particularly if you don’t need to step out again until tomorrow.

Gloria Allred's Lovely October Roast

A delicious burn you may have missed.

Civil rights lawyer Gloria Allred announced today that a client of hers will be filing suit against President-elect Donald Trump for sexually inappropriate conduct. Allred and her client revealed more specifics this afternoon during a press conference, but to get more background I’ve been reading about Allred’s work on this issue to date, and it seems I missed an incredibly good burn she delivered back in October.

See, after footage leaked from Access Hollywood of Trump bragging about how easy it is for him to force himself upon women sexually, nearly a dozen women came forward to corroborate that, yep, he has a history of being inappropriate. Trump replied cavalierly, accusing Allred of being in cahoots with the Clinton campaign, at which point she released a public statement:

Please understand that you will not intimidate me. Others who are smarter, richer and more famous than you have tried and failed.

🙂

Good ’tude, Gloria.