Words Bad

But feel so good.

You may, for some reason, feel like swearing today. That makes you sincere. But have you ever wondered about why some words are worse than others? Joan Acocella’s on the case.

For a long time fuck was not considered especially vile. Cunt, too, was once an ordinary word. A fourteenth-century surgery textbook calmly states that “in women the neck of the bladder is short and is made fast to the cunt.” Until well after the Renaissance, the words that truly shocked people had to do not with sexual or excretory functions but with religion — words that took the Lord’s name in vain. As late as 1866, Baudelaire, who had been rendered aphasic by a stroke, was expelled from a hospital for compulsively repeating the phrase cré nom, short for sacré nom (holy name).

Many exclamations that now seem to us merely quaint were once “minced oaths.” Criminy, crikey, cripes, gee, jeez, bejesus, geez Louise, gee willikers, jiminy, and jeepers creepers are all to Christ and Jesus what frigging is to fucking. The shock-shift from religion to sexual and bathroom matters was of course due primarily to the decline of religion, but Mohr points out that once domestic arrangements were changed so as to give people some privacy for sex and elimination, references to these matters became violations of privacy, and hence shocking.

If you can take some time out from your monologue of nonstop profanity there’s more to read here.

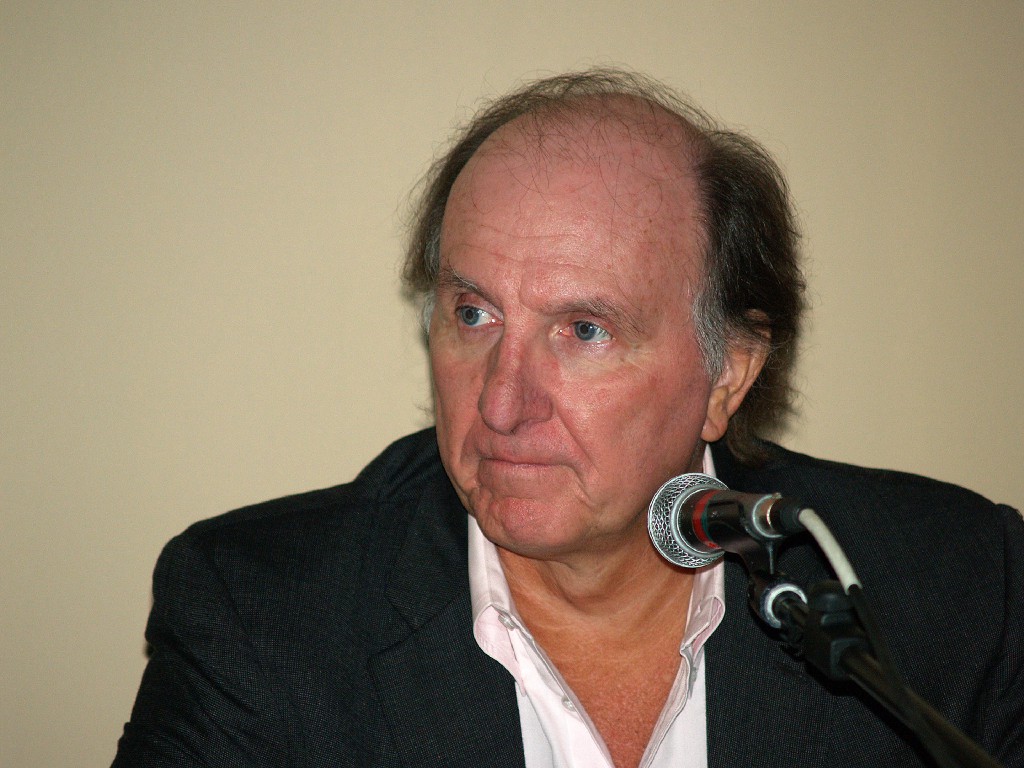

Wayne Barrett, 1945-2017

And now he’s dead.

Yesterday long-time New York City reporter Wayne Barrett died in Manhattan at the age of 71. Barrett’s 27-year stint writing for The Village Voice, eventually taking over the Runnin’ Scared column, which was a beat devoted exclusively to muck-raking in its most elemental form, was one of the greatest runs in investigative journalism, if for only the number of powerful figures he hounded — Sen. Alfonse D’Amato, Rev. Al Sharpton, State Senator Sheldon Silver, Mayor Ed Koch and Mayor Rudolph Giuliani.

Barrett was solidly in the tradition of shoe-leather journalism, holding public figures to account, and was the product of a culture at The Voice that produced a long line of journalists — Barrett, Nat Hentoff (who also passed a week ago), Jack Newfield, Ken Auletta, Tom Robbins, William Bastone — whose scrutiny was regarded warily by the establishment, in a way difficult to find a contemporary parallel. As Barrett said about himself and his colleagues, “We are detectives for the people.”

His first book, City For Sale: Ed Koch and the Betrayal of New York, (co-written with fellow NYC legend Jack Newfield) was described at the time by the New York Times as “an engrossing (if sometimes dense) narrative and a convenient way for busy people to catch up on the complexities of recent New York City corruption. But it is also the culmination of a well-known grudge match between two Village Voice reporters (Mr. Newfield has since left for The Daily News) and the Mayor of New York.” Barrett was the sort of reporter whose coverage could easily be construed as a grudge match, from a distance. Another grudge match Barrett left us was with Giuliani, resulting in two books, a general biography and a look at the beginnings of Giuliani’s life-long love affair with 9/11. But the column, and Barrett’s work, was not just about hounding the powerful; Barrett was a columnist, with a weekly obligation. One week might be a facet of his ongoing reporting on Rudy, and another details of a flailing campaign of a Kennedy, and another tracking down unfolding details of the Deutsche Bank fire. His interests were parochial; it’s just that some of the most powerful people in country worked in his parish.

As a former intern of Barrett’s, writer Adam Weinstein, wrote in Mother Jones in 2011, “To politicians, pundits, and civil servants, Wayne is a journalistic Marine Corps: no greater friend, no worse enemy.”

Weinstein is only one of a storied network of journalists who got their starts interning for him. Jen Snow, Director of PR and Brand at Russ & Daughters, who was at the time executive assistant to the Editor in Chief and tasked with staffing Barrett’s interns, said, “Among Wayne Barrett’s talents was his gift for identifying and then teaching and nurturing (definitely not the word he would have chosen, but true nonetheless) so many young people who would go on to become brilliant investigative reporters, writers, and editors.”

Sam Dolnick, senior editor at the New York Times, was one of the interns. “He had a crew of interns, like six or eight at a time. My internship was my journalism school,” said Dolnick. “He’d have eight storylines running in his head at once, and he’d have us chasing shadows we barely understood. At end of day, we’d each file memos, just type up everything in our notebook from the day.” And when the stories ran, the interns would wait for copies, scanning to see which mysterious detail would make print.”

Emily Weinstein, Deputy Food Editor of the New York Times, was another. “He’d given over his tiny, windowless office at the Voice to his intern operation, lining the walls with metal desks and filing cabinets. We’d crowd around the speaker phone every morning to get our directions for the day from Wayne, who oversaw everything from his home in Windsor Terrace,” she remembered. “He’d call out your name and tell you to call the teacher’s union, to go to the courthouse in the Bronx and dig out files. It was awesome.” “He was amazing, a mensch and a fighter and a generous mentor, an old-school pain in the ass for the bosses of this world and a truly incredible force for democracy — a great New Yorker and a great man.”

Barrett famously was laid off from The Voice in 2010, an act that also cost the paper the services of his long-time colleague Tom Robbins, who resigned in protest. This resulted in a laudatory round of appreciations and tributes (and one goodbye note).

In his final years, Barrett was most popularly known as an expert on Donald J. Trump, the subject of Barrett’s reporting for decades. As the candidacy of Trump shed improbability, Barrett’s 1992 expose of Trump, Trump: The Deals and the Downfall was republished in 2016 with new material as Trump: The Greatest Show on Earth: The Deals, the Downfall, the Reinvention, and Barrett was a frequent guest for television and radio shows to discuss what he learned of Trump over the years.

Barrett was reporting to the end. As Robbins tweeted yesterday upon learning of his death:

On the drive to the hospital where he breathed his last, Wayne Barrett was still doing interviews for a big, tough story on Donald Trump.

He was 71.

Things I Read This Week And Liked

Friday reading roundup

The incredible plot twist is that now these “capitalist investors” use feminism to sell us clothes! Because feminism is cool now! We are told that everything from “period panties” to “granny panties” to high-end couture most of us cannot afford can be feminist. Don’t let all this canny marketing distract you from the fact that wearing high-waisted underwear is not in fact liberation work.

Shopping is shopping and political action is political action, and no matter what anyone says, it’s very hard to blend the two in a sincere way that actually results in the kind of political change we so desperately need.

Buying Feminist Merch Is Not Political Action

In these dark times, we all need someone to look up to. Me. That’s why I’m giving you this new Gorillaz song, a lightning bolt of truth in a black night.

Holy Shit Gorillaz Just Dropped Their First New Song in Six Years – Noisey

In 1951, after Gen. Douglas MacArthur was removed from Asia by President Harry Truman… the furious congressman took the floor of the Senate to call for the president’s impeachment. “This country is in the hands of a secret inner coterie, which is directed by the agents of the Soviet Union,” he said to a round of applause. “Our only choice is to impeach President Truman and find out who is the secret invisible government.”

Hm. Sounds familiar. Anyway, the 1950s were really crazy.

I was able to #2 at the rest stop and am feeling light as a feather.

How Fun For You: We Are Live Blogging Our Interminable Drive to Washington DC

Mm, clicky: Deer eat flesh! | Some colleges have more students from the top 1% than the bottom 60% :-))))))) | You can sing the “Simpsons” theme song at karaoke| The Tonya Harding movie is going to be called “I, Tonya” which is a lot like “Me. I Am Mariah… The Elusive Chanteuse”

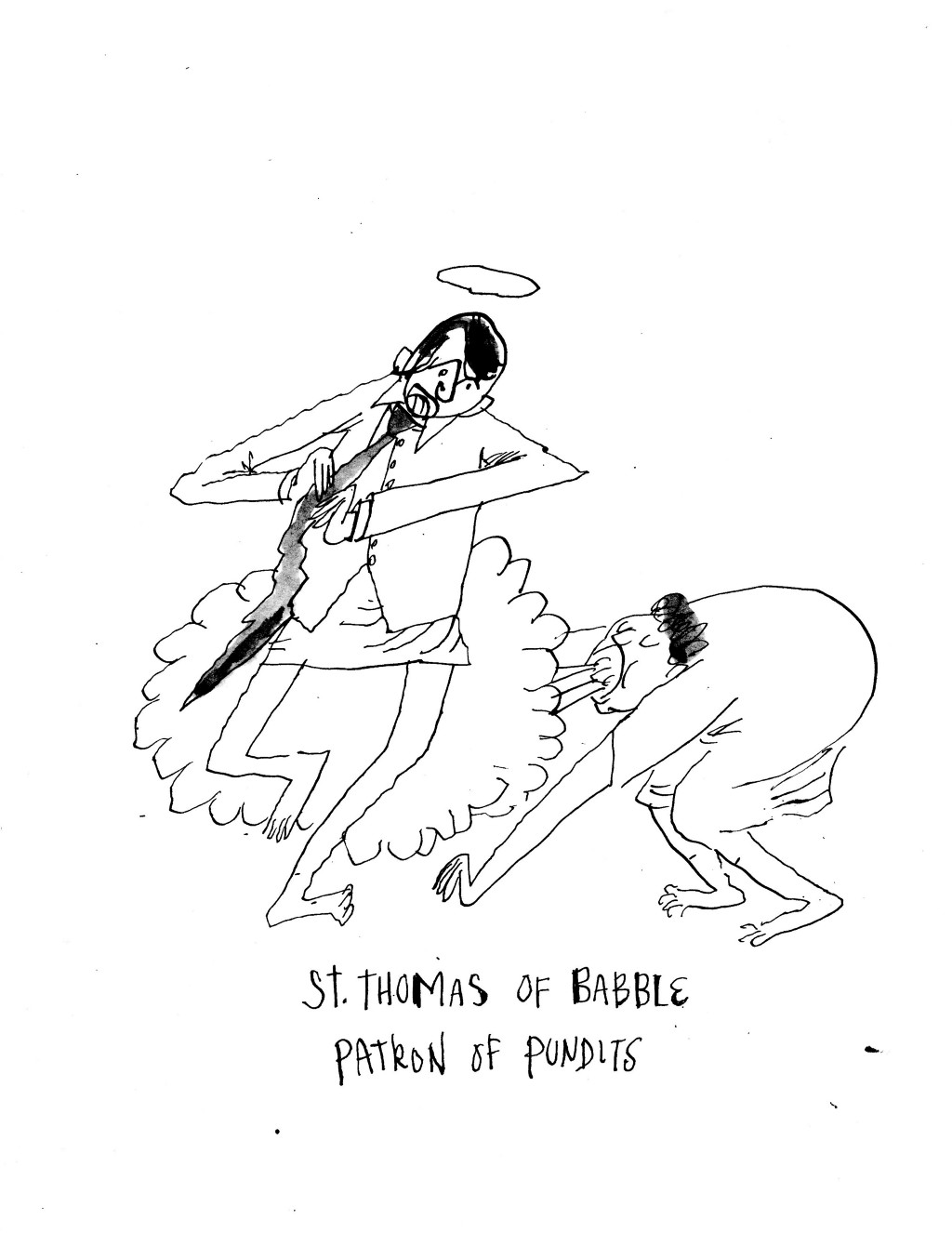

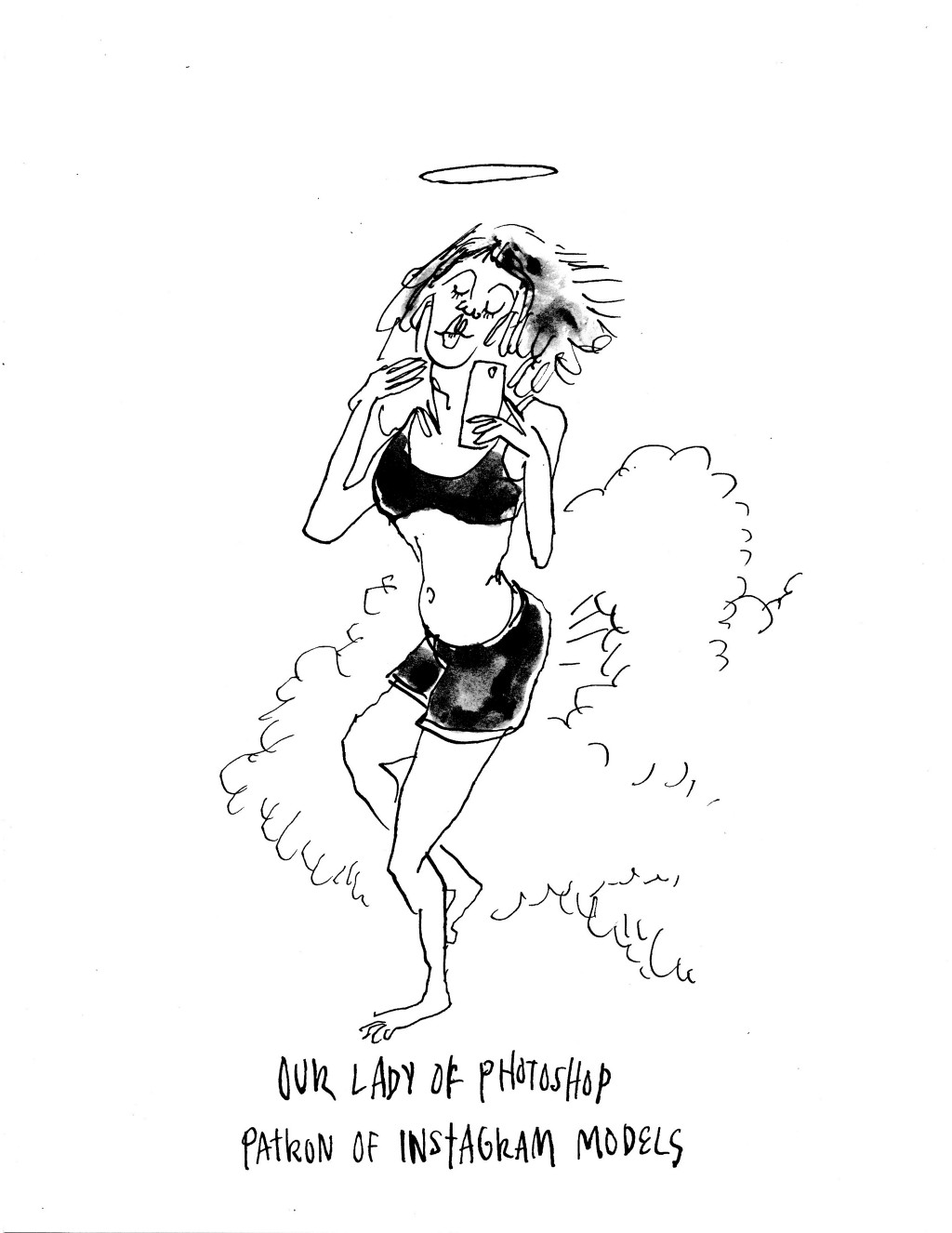

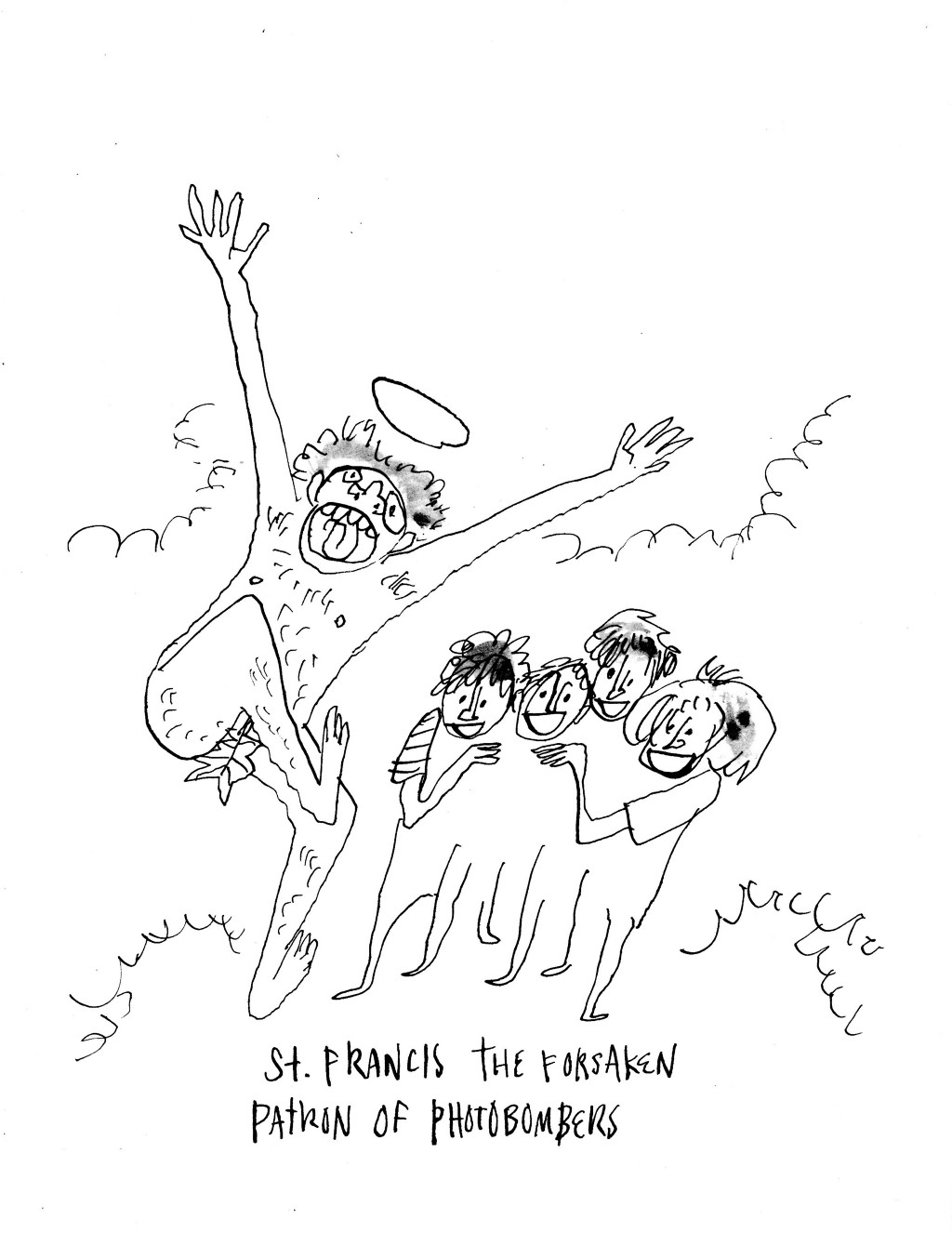

Modern-Day Patron Saints

Illustrations by Jason Novak

Adam Bessie is a San Francisco-Bay Area based writer whose comics n’ cartoon collaborations have appeared in The Atlantic, The Boston Globe, The Nib (and more at adambessie.com).

Jason Novak is an Oakland, CA based cartoonist. His latest book is How To Be Perfect (with poet Ron Padgett, Coffee House Press).

Our Dreamer in Chief

Barack Obama and the stories he told.

If you’d written it up that a man, descended from slaves, the product of a single parent home and an heir of Chicago’s South Side, would not only graduate from that country’s preeminent institution of law, but become the first black editor of its preeminent publication; only to later harness the reigns of a senatorial seat, and ascend to its country’s highest elected position for dual terms, then that notion, your plot, would be deemed unlikely at best. An editor might point to your protagonist, thumbing at his glasses, frowning, mouthing the syllables in their entirety — Barack?

From Paul Beatty’s Gunnar Kaufman, to James Baldwin’s John Grimes, to Junot Diaz’s Oscar Wao, America had no shortage of narratives of “childhood, the conflict of generations, provinciality, the larger society, self-education, alienation…and a working philosophy,” (Jerome Hamilton Buckley, Season of Youth.) Obama’s public legacy is a genre in itself. In cultivating his very American narrative, he rebranded the country’s approach to its own journey, and the public’s faith in that relationship. He believed that we believed.

Obama’s faith in story, and his faith in his constituency’s faith in story, allowed him to approach our country with possibility. He (still) holds his hopes in our hope in ourselves. In a conversation with Michiko Kakutani, he described the revelation of connecting narrative with public service:

I was hermetic — it really is true. I had one plate, one towel, and I’d buy clothes from thrift shops. And I was very intense, and sort of humorless. But it reintroduced me to the power of words as a way to figure out who you are and what you think, and what you believe, and what’s important, and to sort through and interpret this swirl of events that is happening around you every minute… The great thing was that it was useful in my organizing work. Because when I got there, the guy who had hired me said that the thing that brings people together to have the courage to take action on behalf of their lives is not just that they care about the same issue, it’s that they have shared stories. And he told me that if you learn how to listen to people’s stories and can find what’s sacred in other people’s stories, then you’ll be able to forge a relationship that lasts.

Years later, he’d defer to our collective stories in 1995’s Dreams From My Father:

Our sense of wholeness would have to arise from something more fine than the bloodlines we’d inherited. It would have to find root in Mrs. Crenshaw’s story and Mr. Marshall’s story, in Ruby’s story and Rafiq’s; in all the messy contradictory details of our experience.

And it was a notion he repeated in his final major speech as the first black president of the United States of America, quoting Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird:

You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view, until you climb into his skin and walk around in it.

But throughout his presidency, Obama’s hope in narrative was caricaturized and flattened. It was mystified, overhyped, ridiculed, and praised. In Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah, her characters approached it as slightly unbelievable:

“He just makes me feel good!” Marcia said, laughing. “I love that, the idea of building a more hopeful America.”

“I think he stands a chance,” Benny said.

“Oh, he can’t win. They’d shoot his ass first,” Michael said.

“It’s so refreshing to see a politician who gets nuance,” Paula said.

While in Teju Cole’s Open City, the narrator’s relationship to an individual’s direction felt more tenuous:

Each person must, on some level, take himself as the calibration point for normalcy, must assume that the room of his own mind is not, cannot be, entirely opaque to him. Perhaps this is what we mean by sanity: that, whatever our self-admitted eccentricities might be, we are not the villains of our own stories. In fact, it is quite the contrary: we play, and only play, the hero, and in the swirl of other people’s stories, insofar as those stories concern us at all, we are never less than heroic.

In an essay for The New Yorker, Cole actually approached the pitfalls of that allegiance to narrative, and how Obama’s presidency may have cauterized it, turning him inside out of himself:

How on earth did this happen to the reader in chief? What became of literature’s vaunted power to inspire empathy? Why was the candidate Obama, in word and in deed, so radically different from the President he became?… I wonder if the Presidency is like that: a psychoactive landscape that can madden whomever walks into it, be he inarticulate and incurious, or literary and cosmopolitan.

The president’s relationship to story wasn’t limited to a particular political agenda. The notion was awe-inspiring, and no less alluring to any number of storytellers. The New York Times runs a series of author interviews entitled “By The Book”, and among the column’s questions was an exploratory one: if you could require the president to read one book, what would it be? Some interviewees towards the president’s advocacy (Louise Erdrich called Obama “an extraordinary advocate for Native Americans”, recommended Jaimy Gordon’s Lord of Misrule), while other acknowledged the president’s reputation as a bookworm (Jacqueline Woodson said that Obama and the First Lady had “probably read anything I’m just learning about”), while other authors dared to look forward, past the Obama presidency (Daniel Alarcon quipped that it “depends entirely on which president you’re speaking of. Obama? Whoever succeeds Obama? Their suggested reading lists might be so different as to exist in different wings of a very large library”).

And perhaps that last bit, as much as anything else, is what makes his successor’s prospects so damning: the absence of hope in his story. A rejection of hope in his narrative. After Obama, this is not simply striking, it feels absolutely unacceptable. Because, for many of us, an allegiance to narrative is what we came up on. We cannot imagine a world without it. A world without it is no world to live in. It’s a conclusion the protagonist of our country’s most famous bildungsroman reached:

That’s the whole trouble. You can’t ever find a place that’s nice and peaceful, because there isn’t any. You may think there is, but once you get there, when you’re not looking, somebody’ll sneak up and write “Fuck you” right under your nose.

Most working and middle class white Americans don’t feel that they have been particularly privileged by their race. Their experience is the immigrant experience — as far as they’re concerned, no one’s handed them anything, they’ve built it from scratch… So when they are told to bus their children to a school across town; when they hear that an African-American is getting an advantage in landing a good job or a spot in a good college because of an injustice that they themselves never committed; when they’re told that their fears about crime in urban neighborhoods are somehow prejudiced, resentment builds over time.

That was Obama speaking in the midst of the 2008 election. He hadn’t received the Democratic nomination yet, and Reverend Jeremiah Wright had just tanked his sail. But Obama praised him even so, just like he praised everyone else, and what felt like a ploy at the time proved to be an indelible part of his ethos. Instead of damning the rationales of racists and misogynists and homophobes, or exploiting their motives, or urging them to catch up with the globalized West, Obama diminished logic from the equation. He turned to nonjudgmental tropes. He told a story free of villains, or winners and losers. In the story Obama told, you weren’t garbage for disagreeing with him — your views were simply a product of your narrative. He strove to tell his in a way that had room for you, too.

It’s possible that we won’t live to see the rise of another black president. But when Obama told us, all of us — the canvassers and the DREAMers and the doubters and the seniors and the soldiers and the gays and the racists and the Christians and the Mormons and the Moroccans and the Mexicans and anyone else who was willing to hope — that he really, truly, believed in us, and in our stories, we couldn’t help but believe him, because he believed it so ardently himself:

Show up. Dive in. Stay at it. Sometimes, you’ll win. Sometimes you lose. Presuming a reservoir of goodness in other people, that could be a risk. And there will be times when the process will disappoint you. But for those of us fortunate enough to have been part of this work and to see up close, let me tell you — it can energize and inspire. And more often than not, your faith in America and in Americans will be confirmed. Mine sure has been.

That, I think, was the take-away. That we be here. That we be present in the moment. The narrative — our narrative — can get away from us if we let it, because every society’s inevitability is an illusion, and if we do not take hold of our individual storylines one day we’ll look up and they’ll be gone.

The Party

George Saunders, help me.

Then a guy walks in with a megaphone. He’s not the smartest guy at the party, or the most experienced, or the most articulate. But he’s got that megaphone.

— George Saunders, The Braindead Megaphone (2007).

1.

George Saunders asked me to imagine a party. It’s a fine party, diverse. People are talking, making nice. Some talk about the cheese platter, preferring or avoiding the spicy cheese respectively, others about all the construction in the neighborhood and what’s-to-be-done, others about their recent breakup and what’s-that-new-app. Then, says Saunders, a guy with a megaphone walks in. In my mind, this guy is orange and has no neck and he starts a rumor that J by the cheese platter ate all the good spicy cheese and he wasn’t even invited. It doesn’t matter what he says; what matters about the megaphone guy is that he’s loud. The guy can’t not be heard. Everybody listens. Some listen because they also hate J and want him gone, others because it’s fun to watch a neckless guy yelling — it makes them feel better about their own neckfullness. Regardless of one’s own stance re: the megaphone guy’s ideas, the megaphone guy’s ideas are now ubiquitous. The megaphone guy’s ideas and how the megaphone guy expresses his ideas — his syntax, his diction — are resounding off many tongues, filling everybody’s ears again and again. Everybody is talking about the megaphone guy’s ideas by the oatmeal-chia cookies, in the bedroom by the pile of coats. Everybody transforms from what they were before they encountered the megaphone guy into, now, a spectator of the megaphone guy. What were they saying about their ex-boyfriend’s cologne and did they even like that spicy cheese to begin with? Their whispers, they know it, have become room-tone buzz to the megaphone guy’s bombasts. What’s the point of talking? What’s the point of thinking? Where’s the bar?

Now good and drunk, everybody can abandon the shame of not remembering themselves. They take some delight in talking about the megaphone guy, parodying him, repeating his phrases and mannerism. It makes them feel special, included. They talk about the megaphone guy with their uber drivers on the way home. Everybody took videos of the megaphone guy and they post these videos on their twitter/book/gram/tumblogs. Dislocated from context, the megaphone guy is almost funny — he’s different, he’s strange, he’s something to see, and short of being seen themselves they want credit for having seen something, because they can’t quite remember how it happened, but the megaphone guy made them feel small and dumb and they want some of his bigness, his voice, for themselves. They post and share and soon the megaphone guy and the megaphone guy’s ideas explode into viral-immortal life, J be damned.

The party ends in a blur. That party was not fun. Everybody needed a fun party. Everybody was hoping they’d eat something nice, talk, make some eye contact, feel a little important. But somebody ruined that party, who’s to say who. Everybody gets home, and let’s be honest, their home is not as nice as the party host’s home. How did the party host get such a nice home? Does the party host think she’s better than everybody? What does J’s home look like? That the megaphone guy has a home does not occur to everybody. The megaphone guy doesn’t even really have a face, obscured, as it was, by the megaphone. That the megaphone guy is a person, has a body, sleeps, shits…it’s hard to grasp. Speaking of bodies, everybody is still hungry, still a little drunk, so everybody opens their fridge. In the fridge there’s a stack of kraft singles and half a loaf of plain white bread. Everybody wishes they’d eaten more spicy cheese at the party host’s party. Everybody turns away from their sad fridge. Everybody is very depressed.

In bed, the lights off, the heater clanging — that fucking heater is always clanging, who can sleep? — everybody is thinking about J. Maybe they don’t believe that J wasn’t invited to the party, maybe he didn’t steal the spicy cheese per se, but well, do people really like J all that much? Let’s not forget back in 2001 when J’s friend showed up at the party and knocked over the entire cheese platter. That guy, wasn’t he J’s friend? or, like, his brother? They look alike. It feels like they’re related. Anyway, when you look at J a certain way, doesn’t he look like he’s been eating too much spicy cheese? Doesn’t he have a kind of bloated look? It’s vague. It’s hard to describe, but it just feels like J’s been eating too much spicy cheese, and, well, he must have done something wrong. It just makes sense, kind of.

Everybody sleeps fitfully, as usual. To be honest, it’s probably because everybody’s phone is buzzing a lot, and everybody should really turn their phone on silent when they sleep. Everybody does that sometimes, but not other times. They knows it’s in their best interest, but maybe it’s kind of exciting to hear their phone buzzing? Like everybody has something to wake up to? The next morning, the first thing everybody looks at is their phone. Whenever everybody is anxious or bored, they check their phone. The party host posted a comment on everybody’s video from the party. It reads: “J doesn’t deserve this. How dare you spread this hateful rhetoric.” What?! But it wasn’t even everybody’s fault that the megaphone guy was acting like that! It wasn’t everybody who said those things! How could the party host be blaming everybody for simply witnessing events that occurred at her party? What did the party host mean to suggest? That everybody is a hateful person? A bad person? Maybe J did steal the cheese. How did she know? And what does “rhetoric” mean anyway? Everybody just wanted to feel included in the stupid pretentious elitist party host’s party, eating her stupid fancy spicy cheese. Well excuse everybody for trying to get along nicely. Everybody doesn’t even want to go to the stupid party host’s parties anymore. Everybody hopes that the party host never throws anymore parties again.

2.

Meanwhile, across town, in a cold, heaterless home, J sees everybody’s video spiraling out into the twit/book/gram/blogosphere, hears his good name decried, feels the shame of the megaphone’s accusation in the video’s reverberations, even by those who claim to be defending him. Even in quotation marks, even if crossed out, footnoted, annotated, explained to be false, the phrase “J stole the spicy cheese” is now resounding across the web, megaphoned into eternity. J is afraid. J did not steal the spicy cheese. J is not perfect, but J is not a thief. J was hungry. He was invited to a nice party by the party host. J basically never goes to nice parties, never asked to be invited to a nice party, but the party host sent him a barrage of messages pretty much insisting that he come. So he took his fair share of spicy cheese. So there was a limited amount of spicy cheese to begin with. When J sees the party host’s comment, shaming everybody for posting the megaphone video, J feels like he is supposed to be grateful, but he is not. He feels worse. Why was he dragged to a party by the party host just so she could let in an asshole with a megaphone? It’s like she staged it. It’s like she wanted it to happen. It’s like she created a problem so she could solve it. So she could be a hero. Doesn’t she just love throwing parties, dangling her spicy cheese and then pretending to recoil when something dramatic happens? Doesn’t it just tickle her? Doesn’t it just make her feel important to sober up the next day and admonish all the savagery that she caused? Well, J isn’t an animal, and he doesn’t need saving.

Maybe it is J who responds next underneath the party host’s comment on everybody’s video, or maybe it’s somebody else. Maybe somebody else works for the megaphone-guy, maybe somebody else is the megaphone guy, maybe somebody else is a Russian troll, who can know? But everybody is waiting, everybody swipes, everybody’s head hurts, and when the response comes — “Fuck your parties” — everybody is relieved. Yes, everybody thinks. Fuck your parties. Fuck parties, and fuck you.

3.

Under sterling silver track lights, dimmed and useless given the sun’s cold but bright rays raining through the kitchen’s skylight, elbows on a marble counter recently redone and now streaked with wine and crumbs, the party host is not hung-over exactly, but she is tired. Her back and shoulders ache. Her armpits feel warm and weak from lifting chairs and uncorking bottles. Her temples throb with the satisfaction of another party over, another group of neighbors fed and watered, entertained, briefly but significantly uplifted from whatever keeps them down, and it’s only the reoccurring virtual memory of the megaphone guy and his lies that twists something in her gut, below the belly button above the groin, a natural unpleasantness she’s grown accustomed to, that she feels more or less always, like an internal bunion. It’s always something with parties. Each something is a different something. And she feels these somethings uniquely, but always in the same place, gut-wise.

As she swipes, she sweats, pointer finger steady scrolling through everybody’s comments, their curses, their hate. Twist goes the gut. Poor J. Poor poor poor poor J. J who is good and honest and true. J who represents everything these parties stand for. Everything she stands for. Honest hard work. Decency. Fairness. She does not believe this is her fault and yet, if somebody were to blame her, she would tell them, clear eyed and heavy-hearted: yes, this is my fault. And it would feel like her fault and she would grieve. That is her way.

Truthfully, J reminds her of someone. She thinks it might be her grandfather. She thinks it is somebody ancestral and familiar but distant. Somebody close to the earth, somebody who works with his hands. She didn’t know her grandfather very well and she doesn’t know J very well but she senses in them both the same dignity, the same condiments-of-the-earth kind of vibe. Her father used to tell her stories about her grandfather, how he did things, how he held things, like plates, napkins, cups, how he ate things sometimes, like cheese, and in her mind her grandfather’s hands seem to grip clear Dixie plastic with the same confident but relaxed grip of J’s thick-skinned hands, like they are both holding the tableware of a humble and appreciative God.

Thinking about J fills the party host with both levity and weight. Like she is both expanding and shrinking. Like a raisin inside of a grape. It’s a paradoxical kind of pleasure and pain that she knows well, that feels right, because really, the real truth is that the party host has always and now still believes that she uniquely deserves this kind of pain. She can’t explain exactly why. It’s a sense she’s always had, of both being very very bad and very very good, and her life has become a quest, a daily pilgrimage, for both those feelings of goodness and badness in succession and sometimes at the same time, and the throwing of parties, the offering of her lacquered floors to the shoed feet of neighbors near and far, the buying and cutting and plating and pouring, is both a punishment and it’s own kind of mercy. A house is like a body, and she opens hers doors and gives and gives and gives.

4.

The braindead megaphone has no body. The braindead megaphone needs a guy. What of this guy who picked up the megaphone? Does he have a brain? He does, in fact. He has a brain. He has a face. He has a body, but no neck. He once had a neck. He lost it. It’s painful. To lose a neck. Because of the stares? People are cruel. But actually. There were no stares. People aren’t so much cruel as indifferent. Everybody stopped looking. This guy used to have a neck. A great neck. The best neck. A handsome neck. A rich neck. An educated neck. He lost it. It happens.

He wasn’t looking for the megaphone but the megaphone was there. He happened upon it. From certain angles, it covered up the lack. Of neck. And when he used it, people looked. Listened, and looked. Like old times. Good times. Turns out people need to look to listen.

So he brought the megaphone to the party. The host was an old friend. Not a friend. A person he knew. Same circle. Her parties were fine. Decent parties. Good parties. Ok parties. Could he throw parties? Sure he could throw parties. His home was nicer than hers. Nothing against her home, just his was better. A fact.

So maybe it bothered him lately to attend these parties with no neck and no stares. Not even a side-eye. Like everybody was trying not to look. At him. That hurt. Did everybody know how nice his home was? No. Everybody had never been to his home. Did he want everybody to come over? Sure. Whatever. Fine. If everybody wanted to see his home, he’d show them. He’d never really known how the megaphone worked. He thought he’d bring it. Why not? He’d say something friendly like: “Nice Faberge egg collection!” Or “The Taleggio is richer than the Camembert!” and then make a segue to something like “You know I have a whole collection of spiced Emmental in the fridge next to my wine cellar!” And he’d see. No big deal. No loss. No gain. Nobody hurt.

Nobody will tell you how the megaphone works: The megaphone listens. The megaphone is a mouth shaped like an ear. The megaphone hears everything. There is nothing said, nothing even thought, that the megaphone can’t hear. The megaphone does not understand, but the megaphone seems to know something that nobody knows: what a guy should say when he wants to be heard. And it’s often hateful. And it’s often the worst thing nobody is thinking. And if nobody heard themselves say the terrible, despicable, violent, vicious, heartless, inhuman, unloving, ungrateful, unconscionable things that the megaphone hears, nobody could never face themselves again.

Remember: the megaphone does not have a brain. The megaphone seems to know, but does not really know. Nobody knows. Let’s not forget the brainlessness of the megaphone. It’s important that we not imbue the megaphone with agency, with humanity. Because while the megaphone needs a human hulk to work its illusions, the megaphone itself does not have the brain or the body or the face of it’s hapless host. It’s tempting to hate the megaphone. George Saunders, help me; I want to hate the megaphone. My hate needs a body. My hate needs a face. My hate wants to squish, plunge, sink. When the megaphone speaks, I want to ball up its words, I want to squeeze them, feel them shrink, watch them bleed through my fingers, pummel them, bury them, eat them, anything to make them disappear. Everybody and nobody, can’t we turn off the megaphone? George Saunders, where is the switch? The megaphone won’t stop. I see it on my screens. I hear it my dreams. It’s in my body, my home. How can I remember: the megaphone is only plastic.

Amy Kurzweil is the author of Flying Couch: A Graphic Memoir. Her fiction has been published in The Toast, Shenandoah, Hobart, and other publications. Her comics and drawings have appeared in The New Yorker and elsewhere. Follow her @amykurzweil.

Can Anything Save Us From The Boomers?

You are not going to like the answer.

A member of America’s youth has a plaintive, poignant query as one more Boomer president takes office.

What I want to know is when baby boomers are going to give up their death grip on destroying the world

I am sorry to inform her and others of her doomed generation that the answer is: when they have extracted whatever little of value is left to suck out. They will die with a smile on their face as it dribbles down their chin and then you will be left with the costs for disposing of the corpse. Any other questions?

Related:

> James and the giant

From Everything Changes, the Awl’s newsletter. Subscribe here.

My favorite human being is a tall, goofy man called James.

A few pertinent things:

- James, as you may know, is the name of the main character of a Roald Dahl book called James and the Giant Peach.

- For the nearly four years that my James and I have been together, I’ve had an Instagram account.

- James often stands next to very large things while we are out in the world together.

Maybe you see where this is going.

Here’s James and some giant rocks:

James and the giant city:

James and the giant leaf:

James and the giant waterfall:

James and the giant lake:

James and the giant fire tower:

James and the giant cathedral:

James and the giant bridge:

James and the giant oyster flats:

James and the giant Zapotec ruins:

James and the giant sea:

James and the giant railway:

James and the giant 19th-century sculpture celebrating transportation:

James and the giant gorge:

James and the giant forest:

James and the giant mural:

James and the giant tidezone:

James and the giant atrium:

James and the giant mountain range:

As I was taking this picture: “You’re going to caption this ‘and the giant bridge,’ aren’t you?”

I’ll be documenting installments of James near giant things with the tag #jamesandthegiant on Instagram. If you have someone called James in your life who also has a tendency to be near large things, please tag your pics accordingly!

From Everything Changes, the Awl’s newsletter. Subscribe here.

Bing & Ruth, "Starwood Choker"

I don’t know what you thought was going to happen, but this is happening.

I have no words that can console you at the moment. For this occasion consolation is an object far beyond the power of words to achieve. Here is some music. It will not do the trick either, but it is all I have for you, on this day.

Instructions for January 20, 2017

Shhhh

hhhhhh

hhhhhh

hhhhhh

hhhhhh

hhhhhh

hhhhh

hhhhh

hhhhh

hhhh

hhhh

hhhh

hhh

hhh

hhh

hh

hh

hh

h

h

h

All of these are 8–11 hours long. Play them back-to-back all the way through at least twice before opening any of your apps.