The Wireless Devices Are Taking Over

“The number of wireless devices in the United States now outnumbers the people living here.”

Building Tall

Blech, this photo taken from the Freedom Tower (halfway down that page) makes me want to hurl! Not from all the freedom, just the vertigo.

How Much More Does Candy Cost Today?

“Candy may be dandy…” Actually, that is not true. Candy is at all times dandy, and all of us can testify to that: we were children once, and young. When I was ten I’d bike down to the Open Pantry, and if there was allowance left over after comic books, I’d grab a Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup for a quarter (and, if in a shrewd frame of mind, not eat it directly but throw it in the freezer back home). It was a tiny luxury, only two bits.

Now, 30 years later, with childhood more perilous than ever (what with the confusion over the aims of Occupy Wall Street, and the sexting), is candy still a tiny luxury, or are manufacturers of candy leveraging candy’s comfort into a gold-like inflation? Are even our children not safe from the predatory aspects of the free-market economy? Surely no corporation would be so Snidely Whiplash as to exploit little kids for profit, but let’s investigate anyway.

To measure relative prices through the decades, let’s stick with one representative candy: Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups. You may remember the tagline from the 1970s and early ’80s, “You got your chocolate in my peanut butter!” This was a bit misleading. The Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup experience does not purely consist of a young woman walking down the street eating peanut butter out of a jar, and a young man walking the other direction, chocolate bar in front of him like, um, a dowsing rod. I can’t be the only person who, back then, decided to mix chocolate chips with peanut butter out of a jar to see if I could fake a Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup, and found that, while not terrible, it was nothing like the real thing. The whole is greater than the parts, which is the mystery at the heart of candy bars, and Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup in specific.

Even with an informal survey like this one, which has been narrowed down to a single candy, it’s still not so easy to pin a historical trend down, as the cup is not the only chocolate/peanut butter delivery system that has been utilized by Reese’s. It was for a long time. H.B. Reese first sold the cups in 1920s, in Hershey, PA, using Hershey’s chocolate. The 1920s was an active decade for what we now think of as the candy industry (or, the confectionary industry, as it is known), with Baby Ruths, Heath Bars, Milk Duds, Mr. Goodbars and other candies being introduced. The subsectors of the confectionary industry include chocolate, non-chocolate, gum and snack/cookie/cracker products, which is apropos of nothing, but I do love a good subsector. In North America, the global confectionary industry pulled in $35.4 billion, and has expanded by 6% from 2005 to 2010. This data — as learned from appropriately named trade magazine Candy Industry — is offered to demonstrate that nothing manufactured and sold is so magical, not even candy, as to avoid being an “industry,” a word which evokes all kinds of things, all antithetical to candy.

H.B. Reese made other candies too, but the cups are what persisted, and remained the flagship, even after Hershey acquired the company in 1963. Starting in the ’70s, the Reese’s line diversified, and the branding started before we ever called it that. In addition to the cups came the Reese’s Pieces (popularized, if not saved, by the movie E.T., after M&Ms; turned them down) and various iterations of actual candy bars, like Reese’s Fast Break, Reese’s Nutrageous, Reese’s Whipps, Reese’s Wafer Bars and Reese’s Snack Barz. Not to mention the holiday and seasonal versions that are available. Of course we all know the Reese’s Peanut Butter Egg, which were the highlight of many an Easter basket, but have you heard of the Reese’s Peanut Butter Pumpkin? Or the Reese’s Peanut Butter Tree (which you probably have seen during the holiday season, but did you know that it’s called something as mundane as tree)? And there is even a Reese’s Peanut Butter Heart. This is no doubt a growth sector for Hershey, as those cover only four holidays, and we have many, many more. This might be a good chance to write a letter to Hershey and/or your congressman demanding a Reese’s Peanut Butter Back-To-School Sale Pencil Caddy, or a Reese’s Peanut Butter Abraham Lincoln.

But sticking with only the Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups, the normal ones, the ones that have been around for nearly 90 years: how much did they cost way back when? According to this bio of Harry Burnett Reese, at roughly the time the peanut butter cups were introduced (and it’s a bit messy, as he alternately sold them at small shops locally and to assortment lines for packaging), they were going for a penny a cup. That seems reasonable, so let’s use it as a baseline.

Though mention must be made of certain problems when trying to ascertain consumer products vended nationally: namely, it was a big country, even back then, and, as such, retail prices varied. Even if sold nationally through a rigid distribution system, the retail price of a product was (and is) up to the seller. So was maybe a Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup sold in 1928 for 2¢, or even 5¢ in some places? Sure. But for our (unscientific) purposes, leaps of faith must be made. A penny is as good a place to start as any, because you can’t go lower than that.

Moving forward, polling my parents and my friends’ parents, I found vague agreement that, by 1955, the going price for a Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup, or a candy bar in general, was five cents. I am not going to argue with my parents and the parents of my friends.

In fact, if we are going to assume an equivalency between Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups and candy bars in general (which accords with my own personal memory, and visits to shops researching this article), let’s look at this valuable resource from the website The Food Timeline. It’s The Hershey Bar index, comprised of information given from The Hershey Company itself. It confirms the five-cent price, and then has the price rise to ten cents around 1969. After than, we will ratify the price index levels with our own personal memory: $.25 in 1979 (as mentioned above), up to $.45 by 1991 and $.80 by 2003.

And to jump to now, I stopped in at various locations both in Manhattan and Brooklyn, in nice neighborhoods and less posh environs, and, just as our retail conundrum would predict, prices indeed do vary. Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups are going for anywhere between $.89 and $1.50 in Manhattan, and from $.80 to $1.39 in Brooklyn. So to be lazy and take the average of those four numbers, we get $1.14.

So then, let’s consult the handy Bureau of Labor Statistics consumer price index calculator and run the numbers, giving each of the prices in 2011 dollars:

1928: $.13

1955: $.42

1969: $.61

1979: $.78

1991: $.75

2003: $.98

2011: $1.14

Well then, that’s a pretty obvious trend. I expected these figures to be roughly a gentle increase, mostly because there’s a certain squishiness about serving size — at some point the default Reese’s package contained two cups and instead of one. Also, the actual size of the product does fluctuate over time (see again the Hershey Index). But that increase is not gentle at all. Even if we disregard the 1928 figure as an outlier from a time when national distribution was not the ubiquity it is today, we’re looking at an increase of 271% over the 56-year span between 1955 and now, and not in then-current prices, but in numbers adjusted for the natural skew of inflation.

A dollar and change may not seem like much. In fact, it’s not much, these days. Say you were ten years old in 1989, today’s dollar was then fifty-five cents. So if your niece really really wants a Mounds? No problem, once you’ve convinced her to have a Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup instead. But considering that the real price of this specific candy, the friend of children everywhere, has tripled in the span of a couple generations, it’s pretty clear that children are not primarily thought of as cute and occasionally loud creatures that people have when they settle down, but rather a lucrative market demographic.

Booty Prevented From Jiggling

“If the Booty Lounge is rocking, Detroit police come knocking.” [Spoiler: The Booty Lounge was indeed rocking, and the knocking of Detroit’s constabulary resulted in the cessation of posterior oscillation.]

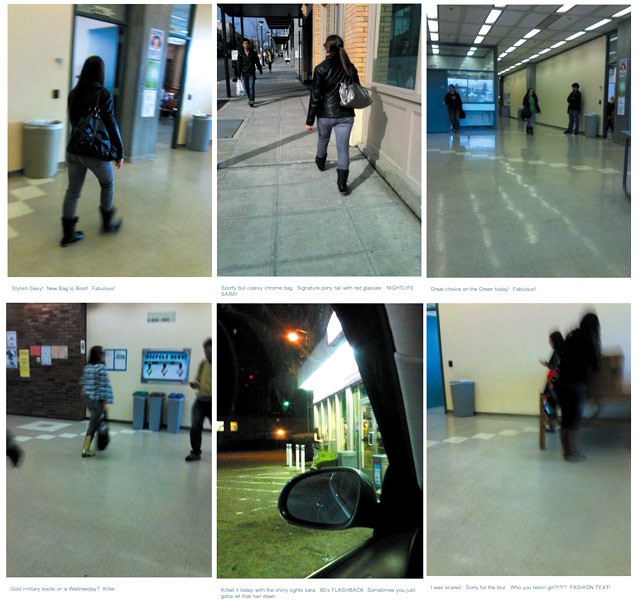

Photos of Sara: The Fake Stalker and His Secret Tumblr

by Mike Barthel

Michael Walker was acting strangely. The 23-year-old Seattle soundman had just been re-introduced to Sara Merker, a college student a couple years older than he was, and the first thing he said was, “Can I take a picture of you for my blog?”

This was the second time Merker had really talked with Walker. The first time was a very brief interaction at a party about a year before. Now Merker was at a bar to meet Nick, a mutual friend, and Walker had tagged along. “I was like, why is this guy being weird to me?” said Merker. “I thought he was kidding. So I said, yeah, sure, let’s take a picture.

“That was the night that Nick finally told me about it.”

Here is what Nick told her: Walker had a Tumblr called “Photos of Sara. She doesn’t know me,” which featured nothing but photos and videos of Merker. That was strange enough. Walker had a girlfriend and didn’t seem particularly interested in Merker, romantically or otherwise. But that wasn’t even the strangest part: Merker hadn’t posed for these pictures. She had never seen any of them before. In fact, she hadn’t known any of the pictures were being taken. Michael Walker had a Tumblr consisting entirely of photos and videos he had secretly taken of Sara Merker.

***

Merker had first met Walker a year before. He’d been part of a large group of guys who went along to a party Merker was helping to throw. “I met him briefly, didn’t talk to him at all, didn’t think anything of it at all,” said Merker. Walker tried to add her as a friend on Facebook afterward, but she didn’t recognize his name and denied the request, since, as she says, she limits her Facebook friends to people she knows “in real life.”

I spoke with Walker by phone when he was in the middle of a cross-country move. Here is how he remembers that night: “I had roommates and friends and whatnot at the time who all vaguely knew her and or tried to hit on her. I was the only one of my friends who didn’t try to sleep with her or anything.”

A few months later, Merker spotted him at school. “I had seen him around and I thought, oh, that’s Nick’s buddy, I wonder if he sees me. And I gave him kind of a head nod and he didn’t respond. So I thought, oh, he probably doesn’t remember me, I only met him once. Totally dismissed it.”

But Walker had seen her. “I took a quick photo of her because I wasn’t able to, like, say hi to her or anything?” he said, inflecting the end of the sentence so it comes out as a question. “I was just following her kind of creepily so I took a photo of her and sent it to a mutual friend who I had actually met her through, and I was like, ‘hey, Merker’s here, I’m following her,’ like joking. I was going to be really creepy and post it on her Facebook as a joke because I thought it would be funny. And then I found out she had defriended me on Facebook.” (Merker, as noted above, remembers this differently.)

So Walker posted the photo to his own blog instead. Called “friends in public,” the Tumblr was a collection of random pictures of his friends hanging out and some, as Merker put it to me, of “people on the street that he was making fun of.” Under Merker’s picture, he wrote: “This is Sara Merker. We were facebook friends once. I found her much more unappealing than my friends did.”

“I guess he posted the one of me, and his friends thought it was funny,” said Merker. “So then he started the whole new blog that was just for me.”

Walker explained how the concept developed. “I was like, what if I took this…reaaaaaally far and made an entire blog obsessed with her and questioning why she deleted me as a Facebook friend at some random point in time,” he said. “’Cause I’ve read a lot of blogs and they’re all bad. And they all take themselves way too seriously. So I was bored and I had some free fucking time and I was like, might as well make a funny joke blog.”

The conceit of the blog was that it was a style blog. The picture captions took a chirpy, upbeat tone, commenting on Merker’s boots or bag and referring to her as a “muse.” (A typical caption, underneath a picture of Merker entering a convenience store: “Killed it today with the shiny tights sara. 80’s FLASHBACK Sometimes you just gotta let that hair down.”) It was as if an entire blog had been devoted to chronicling the taste of a single person who was otherwise unknown, the Sartorialist with only one subject.

Walker said that wasn’t the entire concept, though. He also wanted to “make it kind of funny and stalkery at the same time,” he said. “But never in, like, a super harmful way.”

Walker made a dozen or so posts on the blog and, he says, it managed to attract something of an audience, gaining 300–400 followers on Tumblr. But he very much wanted to keep its existence a secret from its primary subject.

“I didn’t want her to know, because then I knew I would stop caring,” he said. “As soon as she knows about it it’s not funny. It’s all for me to see how much of a creep I can be, I guess.”

Walker said he was aware that it was a potentially off-putting idea, but “knew [Merker] had a good sense of humor,” he said. “I asked my mutual friend through her, do you think she’d be cool with this? I don’t want her to be scared or something, like really be freaked out. He said, I don’t fucking know! And I was like, OK, you didn’t say no. So it started out, and I figured if it’s really creepy, I’ll, like, remove it.”

`

The secrecy soon began to unravel, though. Merker started seeing comments Walker had made on friends’ posts on Facebook. While none referred directly to the blog, she began to get the sense that something was up. “Then I saw him in real life again, and he behaved really oddly toward me,” said Merker. “And that kept happening. He would just give me weird looks, and I would be like, I don’t understand, what did I do?”

When Merker finally learned about the blog, Walker was disappointed. He said he lost any interest in keeping it up, even after “one of my tags popped up in Tumblr’s trending list.” He was excited by the notice “but by then I had found out my friend had just told her about it and I was like, aw, fuck it, I don’t even care.”

“It would have been kinda funny,” he said. “I mean, it’s cool. I’m glad she knows but… at the same time, I might have gotten better at it or something.”

***

“At first I thought it was really funny,” said Merker. “And then I started reading back, and some of the things he posted were not nice. I was really torn. I didn’t know what to think about it at all. Honestly, it reminded me of something I would have done to someone in high school, not when we were 25.”

Merker continued, “The next day I added him as a friend on Facebook, and I changed my profile picture to one of the photos he took of me, so he would know that I saw the blog.” She was going to leave it alone after at that, but “then I thought it would be funny to interview him.”

The interview would be for a communication class she was taking at the University of Washington that summer. The assignment was to conduct a medium-length interview with someone she didn’t know well. Other people interviewed neighbors, family, co-workers. Merker decided to interview the creator of a satirical stalker blog focused entirely on her.

She messaged Walker through Facebook, and at first he seemed receptive. “He thought it was funny,” said Merker. But after an initial show of interest, Walker got skittish, canceling and rescheduling the interview repeatedly. When Merker finally sat down with him, it was only after she had managed to catch him off-guard, saying she was already in his neighborhood and offering to meet at a bar.

Walker had one condition: he wanted to do the interview “in character” as the persona he had established through the blog. That would mean interviewing Merker, too; after all, any blogger who had devoted an entire Tumblr to a single person would certainly take the opportunity to directly question his subject. In the post announcing the interview, he wrote:

When I was nine years old a teacher asked me: “If you could interview any celebrity in the world, dead or living, who would it be?”

I stared stone-faced and cold into her eyes and responded: “Sara Merker”

Merker agreed to the condition and even played along. In an assignment that resulted from the interview, “I decided the best way to respond to him was to continue the joke as if he was a legitimate blogger.”

At the bar, she began with a few warm-up questions, asking what inspired him to start the blog and what his most recent post had been about. Then she got blunt: “So why do you hate me so much?”

“I don’t hate you,” Walker replied. Merker said he seemed flustered. “I’m sorry. You seem nice.” He would continue to insist that he didn’t dislike her even when Sara mentioned the first caption he’d written — “I didn’t find her as appealing as my friends did” — claiming the message was a reference to how a friend of his was “trying to hit on you. He’s a creep.”

Merker remained unconvinced. “I imagine being confronted by someone you’re not going to say ‘yeah it was mean-spirited, I think you’re fucking stupid’,” she said. “Either he didn’t really think it was that offensive or he didn’t expect me to be that aggressively asking him about it. Obviously, he didn’t want me to see it and he knew it was kind of insulting, but he understood that I was seriously confused and thought he hated me.”

At any rate, that was probably the best answer she was going to get, and Merker moved on to more relaxed questions and to joking talk about fashion tips. Walker maintained his persona, presenting himself abasingly by telling stories about getting beaten up in school.

“I would say I was in control,” Merker wrote in her assignment. “The point was to flip who was being scrutinized. He seemed a little flustered and apologetic, like he didn’t expect the questions to be so straightforward.”

Merker’s final product, entitled “interview with a stalker” and featuring Walker’s picture captioned with the single word “Stalker?,” is alternately bracing and revealing; Walker’s interview with Merker, on the other hand, is almost aggressively low-stakes. He begins with a series of apologies: for knocking her hat off, for improvising his questions, for trying to duck the interview, and for not complimenting her purse. But Merker doesn’t take the bait. “It’s fine,” she says. All in all, Walker comes off in the interview as strangely submissive, almost defeated.

***

Why did Walker do it? It’s tempting to blame the Internet; the sense of anonymity we have online can make it tempting to act out. But if you remove the online aspect, “Photos of Sara” is far from novel in its dynamic. As Nancy Baym, a professor of communication studies at University of Kansas and author of Personal Connections in the Digital Age, said to me, if “you go back 20–30 years and you have guys in frats keeping lists of all the women they’ve slept with. So it’s not as though there’s no precedent for invading the privacy of women for the entertainment of other men. Certainly, the Web facilitates this, but it’s not as if this stuff didn’t happen before there was a Web.”

While Merker said she was “shocked” by the idea of a stalker Tumblr about her, she wasn’t too concerned about these unknown photos being public because “I’m not a super private person.” She’s maintained online diaries since she was 12 and currently has a blog. “There’s nothing about what he posted that caused any harm to me or my life,” she said. “I live a lot of my life online, like a lot of people do. I post everything on Facebook. It’s friends-only, but when you have 300 friends, that doesn’t really mean anything.”

Nor is this online openness limited to the young. As Baym pointed out, “People say that young people will talk about anything on the Internet, that they have no sense of privacy. But then you look at what adults are doing, and they’re talking about anything and they have no sense of privacy!”

If anything, what’s most striking about this incident is the way in which it differs from the horror stories we’re used to hearing about the Web. This wasn’t some stranger cyber-stalking an unsuspecting victim; this took place among a group of people who socialized IRL as well as on the Internet. Merker knew Walker, and their mutual social connection was the one that eventually spilled the beans.

“I think from the beginning online socializing has been woven in with offline socializing and telephone socializing,” said Baym. “There’s more and more media through which we can do social interaction. They’ve all just gotten more and more interwoven.”

In the case of the story here, this interweaving of online and offline interaction is true in more ways than one: I was, in fact, the teacher who gave Merker the interview assignment, and you can find my email to her about this story posted on her blog. The title of the post is “HOW IS THIS ANYTHING?”

At the same time, it undeniably matters that Walker’s use of a friend-of-a-friend as the target for a joke became visible to more than just those friends. “The magnitude of it is different, definitely, especially when you consider search,” said Baym. “Blog posts have a permanence they don’t have when they circulate within a small group, and they have a searchability that they don’t have when they are within a small group. They can last for much longer and they can spread to a much wider audience, so certainly the results can be much more damaging online than they can be in a face-to-face situation.”

Baym recounts the experience of one of her students who, while in high school, was the subject of a blog entitled “[student’s name] is a bitch.” “So to this day, if you search her name, that’s one of the hits you get, and she has a very unique name,” said Baym. “This stuff can be harmless and funny, but it can also be incredibly abusive.”

Walker’s own attitude toward his blog and its subject is more complicated. He seemed aware of the loathsomeness of his actions and yet unconcerned about how the blog might reflect on him — now and in the future (indeed, both he and Merker said they did not need their names changed for this article). In fact, encouraging such associations — with “stalker,” a word which he repeatedly invoked in the interview, or “sociopath,” as Merker put it — was part of the point. It’s hard to imagine those being acceptable appellations to have attached to his name if he didn’t also see them as fundamentally fictional: Part of a made-up persona.

And yet the blog became “pointless,” in his words, as soon as its subject learned of it. There’s no reason he couldn’t have continued it, even if Merker was aware of its existence; after all, he could still have secretly photographed his subject. But somehow Merker being aware of it ruined the joke. The power of the story being “real,” with the main subject being unaware of its fiction, was so important that, once that condition changed, the blog became pointless. The performance was not truly public — it was for a select group for people. When the context changed to include Merker’s awareness, the blog’s meaning changed too, it seemed.

Walker, for his part, recently left Seattle for New York. “I just didn’t like Seattle anymore,” he said. “Not enough girls to make fashion blogs about. Lots of those in New York, though.”

Both he and Merker were surprised that I was writing the story at all. As Merker put it on her blog, “How is this anything?” They didn’t seem to think there was anything unusual about the experience they’d undergone.

At the end of our conversation at a local coffee shop, I asked Merker if there was anything else she had to say about the incident. “I don’t have anything to wrap it up,” she said. “It was just really weird. It was funny — I think if he had done it to somebody else they might have been more upset, but he also had a sense of who I was enough that he knew I wouldn’t be too bothered.

“I guess that’s the lesson. If you put something on the Internet about someone, they’re always going to find it.”

Mike Barthel has a Tumblr.

The Fable of Curry Todd

“Tennessee state Rep. Curry Todd, a lead sponsor of a law allowing handgun carry permit holders to bring guns into bars, has been arrested on charges of drunken driving and possession of a gun while under the influence.”

— Let’s all have a good laugh and move on. To linger on this is just like eating the entire bag of candy. [Via]

What Do You Mean Atlantis Is Not The Coolest Fictional City?

Is it because Atlantis is not in fact fictional that it is only ranked at no. 25 on Complex’s list of the 50 Coolest Fictional Cities? I don’t see any other way that that place doesn’t crack the top 5. At least! Regardless of my quibbles (also, I would argue that Tupac’s “Thugz Mansion” is not a city, but, you know, a mansion) the list is great fun.

Phone Bad

Spare a thought for BlackBerry users, who are suffering through their third day of service outages and are also people who have BlackBerries.

The Pill Will Make You Think That Nice Guys Are Actually Attractive

Ladies on the pill, be careful: chemicals may be tricking you into choosing Mr. Right rather than Mr. Right At Doing Sex To You The Way You Need It. “WOMEN on the Pill risk choosing bad sexual partners because they want men who are reliable, a study found. The contraceptive reduced the natural ability to sense who will be good in bed — but helped them spot a good provider…. The effect is so strong that the expert behind the study advised women to come off the Pill while selecting husbands — to make sure they find someone attractive to them.”

Photo by Aletia, via Shutterstock