A Great Rock n' Roll Novel: Dana Spiotta's "Stone Arabia"

A few years ago, there was a lot of talk about the idea of “The Great Rock n’ Roll Novel” and how it had not yet been written. “I’ve yet to read a novel that convincingly sums up the experience and the value of making popular music,” wrote The Guardian’s Graham Thompson, “or that captures the weird, savage compulsion that keeps everyone from Bloc Party to Bob Dylan traipsing around the world, year-in year-out.” In fact, Thompson wondered whether such a novel could ever be written. “Perhaps pop music is essentially worthless as an abstract idea and must be experienced at first hand to have value.”

I was thinking about this as I read Dana Spiotta’s Stone Arabia, which tells the story of a 49-year-old musician who does not traipse around the world year-in year-out, but instead works as a bartender in Los Angeles and spends most of his time holed up in his apartment, recording music that only a few friends and family will ever hear, constructing elaborate album artwork and promotional items, and writing himself a fictional alternate life as a famous rock star — complete with extensive liner notes and made-up record reviews from made-up critics — which he collects, year-in year-out, in a row of trapper keeper scrapbooks that take up an increasingly large amount of shelf space. Robert Pollard did stuff like this in the ’80s, when he was a grade school teacher in Dayton, Ohio, and Guided By Voices was more of a personal hobby than a professional band; him and his friends drinking beer and making songs in his garage.

The book, which was published earlier this year by Scribner, got good reviews when it came out, and was then recommended to me by my friend Stephen, who is a rock n’ roll musician and also a rock n’ roll scholar. So I started reading it and liked it okay in the beginning. But I didn’t love it.

It’s told through the eyes of Nick’s younger sister, Denise — sometimes in the third person, sometimes in the first. The switching back and forth bothered me a little, as did the portions of the story that excerpt Nick’s fantasy writings, which he calls The Chronicles. Most of The Chronicles are written in a style meant to mimic conventional rock-journalism clichés (this is the fictional writing of a fictional character writing in the voices he imagines for other fictional people — layers upon layers upon layers of artifice.) As such, these parts of the book read somewhat clunkily. Here is a passage from the liner notes of a Nik Worth album called The Ontology of Worth: Volume 2, written in the voice of one Mickey Murray, “Greil Marcus Professor of Underground, Alternative, and Unloved Music” at the New School for Social Research.

“Nik Worth, we later learned, had been living as a Buddhist monk in a monastery in New Mexico. He took a vow of seclusion and adopted the Dharma name Jikan, which means ‘silence.’ Would he ever record again? In 1990, we got our answer…”

It’s a problem: to put clunky, clichéd writing in a book for effect. The reader has to read it just the same. (The liner notes of The Ontology of Worth: Volume 2 are three-and-a-half pages long.) Also, it’s a little gimmicky. I don’t think gimmicks are necessarily bad, but in this case, it dragged things down some.

But then! Right around the 100-page mark, the book really takes off. The focus of the story shifts to 47-year-old Denise herself, her struggles with aging and memory lapses, her isolation and an addiction to cable news and internet gossip sites she fell into in the years following 9–11. She describes a series of “Breaking Events” (which she originally titled “My Fragile Border Moments”), basically news stories that she becomes obsessed with, watching the same video clips and interviews with talking heads over and over and over again, culminating with a missing child case in the small Amish town of Stone Arabia, between Albany and Utica in upstate New York. The child’s mother defies her community’s taboo against going on television, risking excommunication, in order to plead for help in find her daughter. Denise describes watching the interview, and here, Spiotta’s prose is beautiful.

“The woman spoke with an odd German torque, a hard-up inflection at the end of the words. She was not beautiful. She was not the picture of Amish beatitude. She trembled. She looked down, she appeared frightened. Her voice shook, and then she couldn’t speak any longer. She glanced up one last time and shook her head a tiny bit as she looked into the camera.”

Denise is devastated by the tragedies that happen to these people she doesn’t know. She sobs for hours, sobs through taking a bath, she sobs herself to sleep. She doesn’t answer the phone. She feels desperate and alone, but she doesn’t talk to anyone about it. “No one is going to comfort you for what you saw on the news,” she says.

It’s so good, this part of the book. It does the sort-of magic trick of making the previous 100 pages seem better in retrospect. Well worth it, or maybe even necessary to get us here. It reminded me of one of my very favorite books to have come out in the past ten years (“One of the best books of the century!” — Dave Bry) Joshua Ferris’s Then We Came to the End, too, has a central chapter that breaks dramatically from what came before it in style and theme. (In Ferris’s case, the switch is more explicit, from the first person plural “we” of a group of office workers, and a mostly humorous tone, to a third-person account of one woman’s being diagnosed with breast cancer.) And in that book, too, the device served to give the book as a whole heft and gravity that had been lacking (no matter what Janet Maslin might tell you) and make the earlier, lighter, more gimmicky stuff seem better than it had prior. It’s so cool, how good writing can control your brain.

Lifted up by the “Breaking Event” chapters, Stone Arabia soars the rest of the way to the end. (This language seems self-contradictory, doesn’t it? A book “takes off” when it gains “gravity.” It’s “lifted” by its “heft.” But it’s accurate, I think. This is what it feels like to read: the increased emotional weight of the story pulls you in, you care about the narrator more than you had previously, it pulls you along, forward, and makes the reading feel like flying. It’s heavier and lighter at the same time. More magic, I guess.) Juxtaposed against Denise’s real-life sadness, which is expressed through her reaction to real-world news stories, Nik’s retreat into rock n’ roll fantasy becomes more poignant. And the book’s main intrigue, which I won’t detail, takes its shape.

I don’t know that I’d call Stone Arabia “The” Great Rock n’ Roll Novel. It’s not only about rock n’ roll, for starters — it’s as much about family and getting older and loneliness and our media-saturated culture. But I’d call it great. The last chapter is a flashback to 1972, when Denise and Nik were latchkey teenagers. Denise and a friend are putting on make-up before going out to a party and Nik comes in and picks up an eyeliner pencil and sits down in front of the mirror. It’s perfect and satisfying in a way that last chapters all too rarely are. And while and I don’t think it “sums up the experience and the value of making popular music” (and I don’t know of a book that could; summing up any experience so wide and varied is, I think, an unfairly tall order for a novel) the argument it makes for artifice as essence, its rendering of the abstract idea of rock n’ roll escapism is certainly not worthless. It’s all about worth. It’s totally valuable.

Foul-Mouthed Britons Can Now Swear Freely

“A High Court judge has ruled that people should not be punished for hurling obscenities in public because such words are now so common they no longer cause distress…. [S]wearing in public, previously a criminal offence across the UK, appears to longer offend the legal system as much as it once did.”

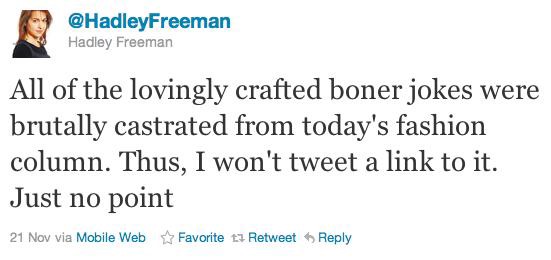

The No-Promo Revenge Tweet, for Employees and Freelancers Alike

Guardian columnist Hadley Freeman shows how it’s done. Displeased with your boss, freelance editor or coworkers? Just refuse to share (but do share why).

Cats Nonplussed

Here you will find a collection of cats who seem bewildered and angry about being forced to don headwear.

MGMT, "All We Ever Wanted Was Everything"

Animator Ned Wenlock directed this excellent video for Wesleyan synth rockers MGMT, to go with the song they recorded for the installment of the Late Night Tales compilation series they recently curated. It’s a cover of a song from Bauhaus’s 1982 album, The Sky’s Gone Out.

Here’s the original.

Here’s Peter Murphy and a reformed Bauhaus performing it live a few years ago.

And here’s Cream.

Your Weekend Project: Ooey Gooey Maple Blondies

Your Weekend Project: Ooey Gooey Maple Blondies

For as long as I can remember, I’ve wanted to enter a baking competition. But I never would, because I’m chicken. The thought of losing… I don’t know, maybe I watched too much or didn’t watch enough Back to the Future as a kid but man, that kind of rejection? Not something I can handle, thanks.

Then a Williamsburg-based outfit called City Reliquary tweeted at me BECAUSE UGH THE INTERNET WHY IS IT THE WORSSSSSST THERE IS AN EMAIL ADDRESS RIGHT THERE IN MY PROFILE asking if I would donate a batch of Crack Brownies to a bake sale fundraiser they were holding for themselves. Oh man, and how flattered was I? So flattered that I agreed to donate a batch of the brownies and also a batch of something new I’d been working on, a recipe that to me is the Holy Grail of baked goods: Ooey Gooey Maple Blondies.

There is a small subset of superior humans who understand that maple is the greatest flavor profile in all the lands and all the seas, and those people just moaned right out loud, sitting there in their desk chairs. Don’t worry, the recipe is forthcoming, so that you can have a weekend project; I just need to work through some things first.

Back to Williamsburg: It turned out that in addition to the bake sale, the City Reliquary was also holding a baking competition. I gingerly asked if I could maybe enter a batch of the maple blondies in the contest, figuring that for sheer novelty, not to mention the fact that they are absolutely delicious — and I say this as someone who actually is kind of modest about her own achievements (no really. Stop laughing.) — they’d be a pretty tough to beat.

I was, um, not correct.

Those motherfuckers. They… they… I can’t even believe they did this. They voted my maple blondies first runner up.

The winner, my contact told me in the most grovelling terms possible, was a “traditional chocolate brownie.” And then! THEN! He had the nerve to ask me to enter the competition again next year, but with the crack brownies.

You know what? No I will not. Fuck you, Williamsburg! A traditional chocolate brownie? That’s what your limited little mind chose as the best of the bar and brownie category? You’ve got about as much imagination as the Upper East Side. Less actually, because you’ve never rolled into a black tie sporting a pair of pants that look like this without the benefit of irony.

Your bad taste and dessert myopia and, undoubtedly, terrible personal odors have robbed me of my will to live. Before I go, though, I do want to give the maple people the recipe. Consider it my legacy.

• In a large-ish saucepan, melt together 1 stick of butter (that’s 8 tablespoons or 113.4 grams, for those of you who are metrically oriented) (I don’t know, okay! I just used some converter thingie?) and 1 cup of brown sugar, stirring frequently to combine.

• Pull the pan off the heat and stir in ½ teaspoon of maple flavoring, ⅓ cup maple syrup and 1 teaspoon salt. Give everything a chance to cool off so that when you stir in the egg you don’t wind up with scrambled maple eggs, because yuck.

• When things have chilled out, go on and mix in 1 egg and 1 cup of flour. Pour the batter into a greased 8”x8” pan and bake the blondies at 350 for 20 minutes. That’s all she wrote!

A word about maple flavoring: It can be a teeny bit hard to find, but any decently sized grocery store should carry the imitation stuff. If you’re a snob — *side-eyes certain editors* [Editor’s Note: Yesss?] — pure maple flavoring/extract exists to validate the fact that you’re an asshole. [Editor’s Note: Correct! See here!]

I guess at this point I could suggest that you make a batch of these and a batch of Crack Brownies and bring them down for your very own bake-off at Zuccotti Park, but honestly I’m too depressed to do anything other than lie in bed and weep gently for the sorry state of my life.

Jolie Kerr is never opening her oven again, except to stick her head in it. Photo by “bogieharmond.”

Let's Go Europe, NBA Edition

by David Roth and Bethlehem Shoals

Paris or Phoenix. Barcelona or Oklahoma City. If you’re planning a vacation, these aren’t difficult choices. And if you’re pursuing a career in professional basketball it’s barely a choice at all. For all the fringe perks of gig hooping in Europe, playing in the NBA offers better pay and a higher public profile than playing anywhere else, as well as the opportunity to be posterized by Blake Griffin and endure reliably wrongheaded, weirdly passive-aggressive criticism from TNT’s Reggie Miller.

But because of the long-running lockout, the NBA seems likely to make a lengthy stop in federal court before returning to the hardwood kind. This means that America’s ballers are not making the easy-seeming choice between the Los Angeles Lakers and the Philippines Basketball Association’s Tender Juicy Giants — their choice, now, is between an overseas basketball job and a gig disinfecting the massage-chair at Brookstone. The question, then, is where to take one’s talents. We asked a few international NBA players the same question: Why should American basketball players consider playing in your home country?

TONY PARKER, FRANCE

“France is my home, obviously, so I’m biased. This country made me the player I am, and while I made a few All-Star teams in the States things are just different over here. I asked to review Bordeauxes for Le Monde, and they just said, “Tony, there is always room for you in the wine section of our newspaper.” I mean, I’m a celebrity in Texas, but back home I’m actually a real movie star!” — note: Parker starred with Boris Diaw, Charlotte Rampling and Vincent Cassell in 2009’s La Donc Galactique, a French version of the 1996 Michael Jordan vehicle Space Jam — “A lot of that has to do with me being French, so I don’t know that everyone else would have the same experience. But I can really recommend playing in France to guys like Tony Allen and Tony Battie. Really anyone named Tony. They say it ‘TUH-nee.’ It’s adorable.”

DIRK NOWITZKI, GERMANY

“As a young man, I turned cartwheels and tooted on my saxophone in the Black Forest. It made me the ultimate soft-focus basketball weapon. Later in life, weighed down by failure, I wandered the countryside until I figured out the exact shape of my soul. Germany is a land of precision and metal, but above all, it’s a place of learning. Who cares that we have the most important, and vital, economy in the EuroZone (our choice of name, by the way)? We are a virtual theme park of self-discovery. The NBA has taken a holiday, maybe, but Germany will teach you things about yourself you never knew. Or wanted to know. Or would ever believe, if not for the imperative suggested in even our most kindly dinner menus.”

ANDREI KIRILENKO, RUSSIA

“Oh wow. My advice to anyone who wants to play in Russia is to get extremely comfortable with beets, and also to develop a very favorable opinion of Vladimir Putin. Without that, you’re pretty much fucked. Also bodyguards. Can’t emphasize that last bit enough.”

VLADE DIVAC, SERBIA

“The quality of play here isn’t as high as it was during the 1980s, I admit, before a lot of the best players went to play in the West. But there is still so much that’s great about playing basketball in Serbia. It’s a very advanced and open basketball culture today, not like when I was young and many teams did not even let players eat prdzyrzcski” — note: a Serbian boiled dough-nub traditionally filled with walnuts and veal — “during games. The coaches are still okay with you smoking cigarettes while you’re playing defense, too, which is great for me. And with all due respect to the people of Sacramento, I think the Serbian fans are the best in the world. The example I always use for this is that Peja Stojakovic recorded two albums of jazz guitar that both went to number one on the Serbian charts” — note: these were 1999’s III and 2003’s Perimeter Explorations — “and this is despite Peja’s being terrible at jazz guitar, and jazz guitar also being terrible.”

JAKE TSAKALIDIS, GREECE

“It’s a little-known fact that I began life as a Georgian, before becoming a citizen of Greece around the time my semi-professional basketball career began. It’s pretty well-known that I am no longer in the NBA, to the extent that such a thing exists nowadays. My proposition to players thinking about joining me here is simple: Greece is a land in shambles, and ripe for conquest. I returned here not cloaked in failure, but with major dreams of making more cash, and wielding more power, than ever I could have as a back-up’s back-up in America. Here, I am no mere athlete — I am something more akin to a warlord, or a king, or Bulgaria’s wrestlers Josh Childress came here hoping to change the economic leverage available to American players and perhaps permanently alter management-labor relations. Now he commands a private army, lives in a floating circus tent high above the clouds, and comes down occasionally to play ball and collect debts. When this country collapses once and for all, it will land in our welcoming arms. Do you have what it takes?”

David Roth writes “The Mercy Rule” column at Vice, co-writes the Wall Street Journal’s Daily Fix,, and is one of the founders of The Classical. He also has his own little website. And he tweets inanities!

Bethlehem Shoals is one of the founders of The Classical and FreeDarko.com as well as the Twitter account @freedarko.

Photo by Aitor Bouzo Ateca, via Shutterstock.

Real Men Will Put Up With Whatever They Have To In Order To Get Some

“In a turnaround on the usual stereotype of macho, testosterone-laden guys making risky life choices, a new study finds that young men with higher levels of this sex hormone are more likely to accept safe-sex practices.”

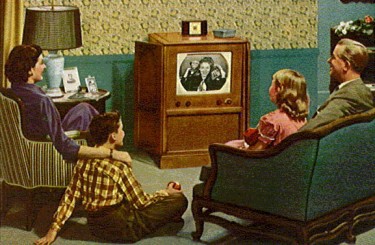

How Much More Do Televisions Cost Today?

Sometime between July and September of this year, you may have heard that America’s poor are not really all that poor. Something like this bit of wisdom from Heritage Foundation researcher Robert Rector from July 27, 2011:

How poor are America’s poor? The typical poor family has at least two color TVs, a VCR and a DVD player. A third have a widescreen, plasma or LCD TV. And the typical poor family with children has a video game system such as Xbox or PlayStation.

My goodness, that almost makes you wish you were America’s poor, doesn’t it? (Or maybe you already are — congratulations!)

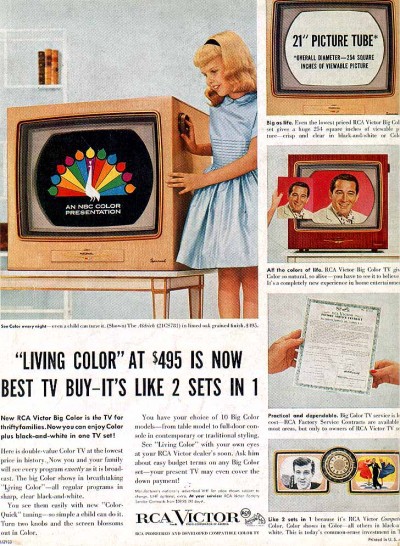

The implied redefinition of ‘poverty’ as ‘abject poverty’ is certainly a conversation starter, so let’s continue the conversation by looking into how much television sets have cost as the decades (decades with differing percentages of poor people) roll past. As we’ve been looking into how much things cost and when they cost it, we’ve been seeing a general trend of inflation above and beyond the increases in the cost of living. Let’s see if this is also the case with television sets.

***

Though we take television for granted, entertainment was not always so seamlessly obtained. By the 1930s we had achieved moving pictures, but we were forced to watch them outside of our homes, with other people. But the research that would eventually reach ubiquity was already in progress, all across the globe. In the United States, a young inventor named Philo T. Farnsworth was at the forefront. In fact, the first public demonstration of his device, the first all-electronic television mechanism, shooting electrons back and forth onto a screen, creating the moving image viewed, in 1934.

It was only a few short years before televisions were manufactured commercially in the United States. Programming began at the same time, but sporadically and locally, so the earliest owners of TVs were like the earliest owners of compact disc players: sitting on a space-age gizmo that could play the only four CDs available. Eventually, production of TV sets was curtailed in 1942 by the War Production Board, to free up resources for the great effort which ultimately won World War Two (our half of it, at least). Before suspension of TV manufacturing, only 7,000 sets were made, insane luxury items that were more conversation pieces than portals into the world of broadcasting, so they were priced like crocodile handbags — the first RCA model debuted at $600 in 1939. Adjusted for inflation (i.e., converting the purchasing power of six hundred 1930 dollars into 2011 dollars), that would be $9,773.

Gathering data on this topic turned out to be not as difficult as I anticipated thanks largely to the exhaustive website TVHistory.tv, which is the work of a fellow named Tom Genova. The site breaks down everything about television — the technology, the networks, the marketing, ephemera — by era and by year. If you want to, grab a few dazzling bits of trivia so that you may win the next dinner party. (First TV remote control? Zenith Flash-Matic, 1955. Was there ever a pre-cable channel one? Yes, until 1946, when the FCC reassigned the frequency.) Mr. Genova’s site is the place to go. And hidden in there is even this page, which is a convenient chart listing how much television sets cost over time. Boom.

However, the problem with comparing the costs of television sets over time is that the thing that we think of as a “television set” has mutated over the generations. Even in the past decade, think of how the cathode ray tube sets have become extinct. Is it fair to compare the cost of 12” console television from 1948, with a Mahogany cabinet designed to centerpiece a room, able only to receive local programming during limited hours (like, say, a Stromberg-Carlson, retailing at $985 installed — or $9,524 adjusted), against a 25” console from 1986, which was designed less as furniture and more as appliance, able to access the hundred or so national cable networks in addition to the various local stations, round the clock (like, say, a Sylvania, retailing at $540 — or $1,115 adjusted)?

Remember also that the true-life color TVs we are so accustomed to took some time to materialize. Arguably, the first compatible (i.e., could receive shows broadcast either in black-and-white or color) electronic color TV set was the RCA CT-100, a 12½” console, which sold for $1,000 in 1953 (or $8,480 adjusted)? And even into the ’60s, when you could buy a ’68 Admiral 23” color console for $349 ($2,270 adjusted), the black-and-white television was not uncommon, maybe at Grandma’s house. It wasn’t until the late 70s (when you could get a ’77 Sylvania 25” color console for $530, or $1,840 adjusted) that production of B&W; TVs was halted.

What about the introduction of complimentary technologies, such as VCRs, which enabled the viewer to not be present for broadcasts, and duplicate programming for re-viewing? Or of the DVD, which took the marketing appeal of the videocassette and introduced near-theater level quality (which happened, incidentally, in 1996, when a Samsung 10” tabletop would set you back $340, or $490 adjusted)? There are a dizzying array of factors that make it almost arbitrary to try to compare these TV sets to one another, starting with the technology and the available programming, including the fact that the variation of prices within a specific time, from the high-end to the low-end product, can be pretty wide, and ending with the evolving relationship that the American family developed with the “idiot box,” during which it went from luxury to novelty to babysitter to omnipresence. Remember how you didn’t have a TV back in the ’90s because you spent your entire childhood soaking in the CRT goodness and wanted to have your own tiny rebellion? Well, you probably didn’t have a rotary phone, either, but you weren’t moved to explain that to people.

Is it fair to compare? Probably not. But we’re answering the call of the Heritage Foundation premise that TV sets are a negative signifier of poverty, so we soldier on. By the way, a TV right now, in the twilight of television’s dominance as a stand-alone industry, as content increasingly becomes platform neutral? J&R;’s will sell me a Viewsonic 27” LCD HDTV flatscreen for $319. That’s a pretty good deal.

***

Let’s stop talking about television sets and talk about poverty for a second, as that is the issue underlying the Heritage Foundation premise. The U.S. Census Bureau is the organization that set the “threshold” for determining poverty — what is commonly referred to as the poverty line. We all know what it means. It’s a number, and if a person’s annual income falls below that number, then this person is officially impoverished for statistical purposes. These thresholds, however, have little to do with whether this person will receive assistance from the government. Those guidelines are put out by the Department of Health and Human Services. They use discretely different analytical techniques to arrive at their figures, which do vary from the USCB threshold, though not by an awful lot.

Basically how it works is this, a statistician in the 1960s working for the Social Security Administration, Mollie Orshansky, developed a sort of a formula to determine what poverty is. The cost of living is determined, pegged to the cost of a “nutritionally adequate diet,” and then numbered up into a fixed proportion of income of a person/family. This figure is adjusted each successive year based on how the Consumer Price Index changes from the year previous.

The Merriam-Webster definition of the word is, “the state of one who lacks a usual or socially acceptable amount of money or material possessions.” Of course, dictionary definitions may vary, but the concept is relative to the standards set by the rest of society.

So is the standard by which poverty is measured open to question? Of course. As federally determined, it’s based on a 40-year-old theory, so assumedly it would be weighted to reflect concern relevant to the time. Perhaps some aspect of the cost of living is overemphasized, and some other aspect is not given enough credence. Perhaps television ownership should somehow be mixed in there, to keep the process of government assistance honest.

For the record, the current HHS Poverty Guidelines are $10,890 of annual income for a single person, and $14,710 for a couple.

***

So we have the prices of a lot of television sets since their inception, and we’ve converted them to current price levels. They are as follows:

1939: $9,773

1948: $9,524

1953: $8,480

1968: $2,270

1977: $1,840

1986: $1,115

1996: $490

2011: $319

As you can plainly see, if you were graphing that, it would make a line that you could ski down. From 1939 to now, there’s a decrease of a little more than 96%. The cost of acquiring a television has absolutely plummeted.

I mentioned at the beginning of this piece the bit of research from the Heritage Foundation that launched this discussion. It’s hard not to have noticed it, because since the original Backgrounder published on July 19, they’ve wasted no opportunity to restate their premise, including another Backgrounder released on September 13, 2011, practically identical to the July 19 Backgrounder, to respond to the annual Census Bureau poverty report (which stated that the poverty rate was up to 11.7%, or 9.2 million American families). Obviously the Heritage Foundation is a think tank that is committed to communicating their message, to give official-sounding ammunition to like-minded politicians and pundits, but why are they so dead-set on viewing American poverty through rose-colored glasses? They are attempting to set the stage for the argument that less discretionary spending should be spent on the poor (because they have TV sets).

From the initial July 19 Backgrounder:

In discussions about poverty, however, misunderstanding and exaggeration are commonplace. Over the long term, exaggeration has the potential to promote a substantial misallocation of limited resources for a government that is facing massive future deficits. In addition, exaggeration and misinformation obscure the nature, extent, and causes of real material deprivation, thereby hampering the development of well-targeted, effective programs to reduce the problem. Poverty is an issue of serious social concern, and accurate information about that problem is always essential in crafting public policy.

The Heritage Foundation, in an effort to tighten government spending so that less revenue (i.e., taxes) is needed, argues that the poor aren’t really all that poor, and as long as they have a TV set (or an air conditioner, or a PS3) should have no assistance.

Now, they do acknowledge the fact that buying a TV is not as prohibitive as it might have been once. From the September Backgrounder:

Liberals use the declining relative prices of many amenities to argue that it is no big deal that poor households have air conditioning, computers, cable TV, and wide-screen TV. They contend, polemically, that even though most poor families may have a house full of modern conveniences, the average poor family still suffers from substantial deprivation in basic needs, such as food and housing. In reality, this is just not true.

Sidestepping the polemics, while researching this it was heartening to discover an item that has declined in adjusted price for once. But to propose that families below the shockingly low poverty line should either be disqualified by reason of TV ownership, or I guess live a life without a television, or an air conditioner, etc., before the social safety net kicks in, is, for lack of a better word, mean. This is poverty that we’re talking about, a relative level of living standards, not destitution. Better for the Heritage Foundation to come out and say what it means, that it believes that the well-being of its citizens is not the obligation of the government, instead of trying to shame 9.2 million families because they watch “So You Think You Can Dance” once a week.

Brent Cox is all over the Internet.

Ads courtesy of TVHistory.tv, used with permission.