Remember the Kingsbridge Armory!

In 2009, you may or may not remember, the City Council nixed the Kingsbridge Armory mall project in the Bronx. The developers of the project were to receive $50 million in exemptions and tax credits — but the Council, after much argument, knocked it down, because neither the developer nor the future mall tenants would agree to pay workers a minimum of $10 an hour. ($10 an hour is basically $21,000 a year, by the way, before taxes are withheld.)

But the developer and its associates wouldn’t agree to do this, so the Council told them to get stuffed. The Mayor got all huffy and passive-aggressive that the City Council wouldn’t let the developer “create jobs” in the Bronx. (He even called it “a great tragedy.”) Amusingly, the developer wouldn’t build the mall without the subsidies, even though it would have likely done pretty well for them.

Mike Bloomberg still opposes mandating wages for publicly funded building projects. Now the lastest version of the bill that would mandate that developers receiving these incentives agree to pay workers that minimum of $10 an hour is going to City Council Speaker Christine Quinn’s desk.

At the same time, a poll released today finds that voting New Yorkers support this “Living Wage” act, to the tune of a whopping 74–19 percent.

The developer of the Kingsbridge Armory mall, by the way, was The Related Companies L.P.; they are the New York affiliate of the Related Group. The chairman of the Related Group is Jorge M. Pérez, who recently had the name of the publicly funded Miami Art Museum changed to the Jorge M. Pérez Art Museum of Miami-Dade County, for just $10 million in cash on top of another $5 million, plus some art. So that’s the dude who can’t pay people $10 an hour.

Higgs and the Certainty of Physicists

by Ann Finkbeiner

The room is 100 percent physicists, 75 percent of them are likely to be under age forty, under 10 percent of them are likely to be female. They’re all unusually quiet, no scrooching, no whispers, motionless.

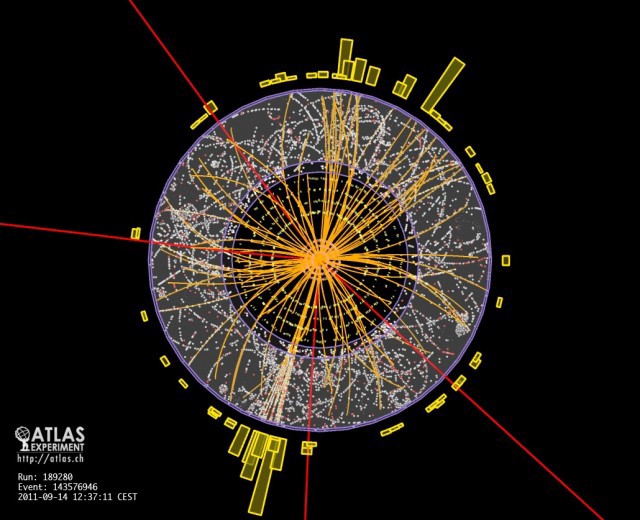

On two screens is the broadcast from CERN, the physics institute in Switzerland, of a scientific talk. Invisible in the air is the theory called the Standard Model, or at least one of its articles of faith, which you can read like it’s liturgy: the first fundamental particles in the universe had no mass; but as the universe cooled, it changed, and during this change a force called the Higgs field condensed into a quantum liquid, and the liquid dragged on the fundamental particles and gave them mass; and in the liquid, waves formed into a particle, and it was called the Higgs. Highly theological, but in the room on the screens is the first physical evidence that the Higgs is a fact. Sort of. Depending. The room has its own force field created by physicists, tense and ready to jump.

The broadcast has turned to questions and the young physicists in the room get tired of listening to people on another continent quibble and a pale, blonde physicist stands up and says, “So. Let’s summarize.”

CERN has collided fundamental particles at enormous energies — hundreds of gigaelectron volts (GeV which the physicists pronounce Jev), over and over and over again, and each time has examined the energies of the particles that came out of the collisions. CERN has done this in two different experiments; the young blonde worked on one of them. He says the experiments together suggest that the Higgs’s energy is around 125 GeV. The physicists in the room are not that interested in the number, which is after all a matter of statistics — 125 GeV just had more hits, showed “an excess of events,” they say. They’re more interested in whether they believe it.

Physicists do the most lovely thing: they quantify conviction. They know what they believe to within four decimal places. They assign to their certainty a number called sigma: 2 sigma, you’re certain to one in a hundred; 3 sigma, to one in a thousand. Physicists remain restless up until 5 sigma, one in a million. In the room, the young blonde is waffling on the sigma; the physicists get pushy: “You gotta give us a number or we’re gonna shoot you.” You can’t really combine the experiments, says the blonde, but combine the experiments and the naive number, don’t take a picture of it, is 4.4 sigma.

Five chances in a million that’s it not true.

Quantification of conviction doesn’t always take the form of numbers. “I believe this one day in five,” physicists say, or “I believe this utterly and completely once a month.” Or: “I bet my house. I bet my grad student’s house. I bet your next paycheck. I bet my car. I bet my old car. I bet my dog but I don’t bet my child.” A Higgs of 125 GeV? You have a coin with a thousand sides, how many flips to come up with a fake Higgs? No, you have an unfair coin, how many flips would prove it’s unfair? The room of physicists, a little frustrated now,

turns to a physicist in late middle age who helped find the last hot particle, the top quark: Well? “I’d bet Mitt Romney $10,000 because he can afford to lose it.” C’mon, is this gonna be for real? The physicist pauses. “Sure.”

Well then. So what. The bible, the Standard Model, predicted the Higgs would be at a slightly lower energy, around 114 GeV. An extension of the bible called Supersymmetry — in which fundamental particles are made of strings coiled in 11 dimensions, and for which no evidence exists — predicted a Higgs that’s higher than 114 GeV. “Watch out,” says a physicist with dark curly hair, “tomorrow you’re going to see statements from supersymmetrists that 125 GeV confirms supersymmetry, and that’s absolutely not true.”

The bible’s opposite — cold hard fact — says that most of the universe is not stuff like us but something invisible called dark matter. Astronomers have been nagging physicists to find dark matter for years. Is the Higgs dark matter? To first even believe the Higgs is 125 GeV, says the blonde, will take more statistics and another year of data; but saying in seven-parameter space that it’s dark matter, that’ll take twenty years. “Twenty years?” says an aging astronomer. He stumps out of the room: “Oh Lord. I gotta keep going now.”

Ann Finkbeiner is a proprietor of The Last Word on Nothing.

Family Dresses Funny

You could view this report as the heartwarming tale of a family brought together by its tradition of dressing up in comical holiday outfits, yearly proof that despite the passage of time and the differences that come between us as we grow and change, Christmas stills retain the magic of our earliest childhood memories, when all was wonder and joy. In fact, that is exactly how I suggest you view it, because the alternative — the story of a group of adults held hostage by a megalomaniac matriarch whose need to humiliate her spouse and offspring on a yearly basis is probably driven by resentment and regret over the paths her life never took while she gave up the best years of her life to her family — is just too grim to contemplate. And too real.

Blackwater and the "Military Aged Males" of Iraq

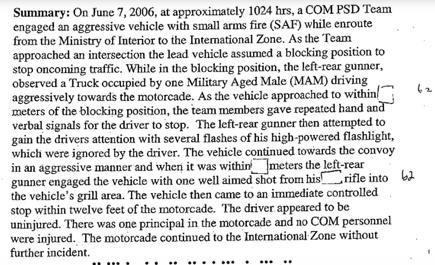

John Cook’s 4500-page Blackwater document dump is incredibly engrossing. These little stories! It’s like, “we shot this dude’s car, then everything was okay.” What a nightmare Baghdad must have been (for Iraqis, I mean).

The Connie Converse Double Album That Never Got Crowd-Funded

by L.V. Anderson

Sometimes, Kickstarter campaigns don’t meet their funding goals — but it’s not the end of the world! In this series we explore what happens next. Up first are Dan Dzula and David Herman, the founders of Squirrel Thing Recordings. The label’s first album, How Sad, How Lovely, was a collection of songs by an obscure and enigmatic singer-songwriter named Connie Converse, who recorded in New York in the 1950s without ever finding an audience for her music. After giving up songwriting and working as an editor for several years, Connie packed up her belongings, said goodbye to her friends and family and disappeared. No one ever heard from her again, and her car and body were never found.

This fall, Dan and David created a Kickstarter to raise money for a special-edition, two-disc vinyl set of Connie’s recordings that would include specially commissioned artwork and a bound collection of Connie’s writings. After 30 days, David and Dan had gotten pledges for only $2,036 of their $15,000 goal.

L.V.: First off, who was Connie Converse?

Dan: Connie was a woman who dropped out of college and moved to New York to be a songwriter in the late ’40s, and she was in New York through the ’50s. She had a good day job, but she spent a lot of her time writing songs and a lot of her energy trying to get other artists and other musicians interested in her songs.

When you’re talking to people who don’t know her music, how do you describe it to them? What’s your little elevator spiel to describe what her music sounds like, in terms of artists that people know?

David: Our Kickstarter campaign might have been more successful if we had had that down. I guess I describe it as folk-inspired but with a Tin Pan Alley kind of flavor to it. Definitely that sort of Depression-era songwriting comes into her more so than pop music of the ‘50s.

Dan: What strikes me is how simple her songs are and often how narrative-driven they are, and also how elegant they are. Really so restrained.

David: I always thought of her as a really efficient songwriter, or an efficient lyricist. She was always really good at like making really potent lyrics, meaning that she fit the most meaning into the smallest amount of words possible.

Dan: In the ’60s, she moved to Michigan, created for herself a whole new career in academia.

David: She started as a secretary; pretty soon she was an editor of the journal there, and then she was the managing editor of the journal.

Dan: For ten years, she built this new career, and as she approached her 50th birthday in 1974, evidently she felt like she needed to move on, to try and find herself or reinvent herself or to find life somewhere else.

David: So in 1974, not very long after her 50th birthday, her brother and his family, they took a summer trip every year to a lake in Michigan, I can’t remember which one, and she decided not to go. And, as far as we know, she packed up all of her stuff and left her apartment and left a couple of goodbye letters for people that she knew. And she went away.

Dan: Her brother has accepted that she committed suicide. Within ten years after Connie’s disappearance, Phil contacted a private investigator. And, basically, the private investigator told him, “Look, I might well find your sister, but you need to know that if I find her, that doesn’t mean she’s coming back. It doesn’t even mean that she’ll talk to you.”

David: “If I find her, and she doesn’t want you to know about it, then I can’t tell you about it.”

Dan: “It’s her right to disappear.”

I didn’t know private investigators operated on that code of ethics.

David: They’re not all like that guy in The Big Lebowski.

Dan: That seems to have hit Phil Converse very heavily. That resonated, it made sense to him, that it’s her right, and since then, as a decision to disappear, he has respected that.

Tell me about your background. How did you guys meet?

Dan: David and I met at NYU. We worked on a theater piece together as co-sound designers —

David: Which we thought would come crashing to a miserable halt.

Dan: It’s funny, actually, I didn’t want to do the project. It was my college girlfriend’s theater project, and she was forcing me to work with this new guy David — or new to me — and I was just resisting… and as it turns out, I met my best friend! Anyway, since college, I’ve been working as a recording engineer and a music producer and composer, doing mostly commercials, advertising. And for a couple of short spells, we’ve worked together in the same studio. But David has had his own trajectory.

David: Oh, yeah. I was working in theater for a while, for a few years out of school, doing audio, and then wanted to start working in studios, and Dan’s studio, the place where he was working had an opening, so I worked there for a while, and now I actually work for WNYC as a sound engineer.

Connie’s music has been featured on WNYC’s “Spinning on Air.” Did [“Spinning on Air” host] David Garland find Connie’s music through you?

David: Well, we found Connie through David Garland. Not personally, we didn’t know him; we listened to the show.

Dan: So this man Gene Deitch, from Prague, he has been sort of a recording hobbyist for his whole life, and at some point maybe in the late ’90s or early aughts, his son reminded him that he had some very early John Lee Hooker tapes that he made before John Lee Hooker was signed to a label, in 1949, I think. And it was on that release that he was brought to New York by David Garland and WNYC, and they did a “Spinning on Air” special —

David: Playing Gene Deitch’s records.

Dan: — and Garland had asked him to play some more random and unique things that he had done, or recorded in the last 50 years, and yeah, she was one of those. And he talks, Gene, on that broadcast, it was in 2004, he talked about her for a minute, played her song, and that was it. And I was in the car with my brother, and it just like — dumbfounded me. And over the next several years, I was always trying to find information on her, and just couldn’t. And that was really frustrating.

You remembered her name and remembered the song and that was it?

Dan: Yeah. And then after a couple of months, I went to the WNYC website and did a very crude recording of their webstream — it wasn’t downloadable — just so I could listen to this woman’s song. It was “One by One.”

And I always wanted to know more about her, I always felt like if no one else was prepared to work with her music that perhaps I could. And I finally just got sick of never knowing, and it took me three years to — I don’t know if it was to get up the courage or what — but three years to write a letter to Gene Deitch, and he responded immediately. He was so excited to hear of my interest, and excited to hook me up with Phil Converse. And evidently this project of promoting Connie’s music has been his lifelong mission.

And so How Sad, How Lovely is the first album that you put out, correct?

Dan: Yes.

I think that the story was sort of the allure. Come for the story, stay for the music!

Who do you think the audience for that album is? Do you think you generally drew people in who heard the story and then fell in love with the music the way you did, or do you think they were folk-music buffs who loved it because of its genre?

David: I think that the story was sort of the allure. Come for the story, stay for the music! I think the audience really is people that are searching out those kinds of stories. People that are interested in — what’s the word? — bizarreties. Unexplained things. Those moments of awe that people are always searching for on the Internet. That’s sort of the grail of the 21st century.

How did you come to develop the second project? This was supposed to be two-disc set with other media attached, right?

Dan: Well, over the past two years, we had received emails from people asking us when this will be available on vinyl. Some people have even said, “I will not buy this until it’s on vinyl,” which is also just a funny indicator —

Why do you think that was?

David: People are really into the experience of vinyl. And there’s a lot of crossover between the people who are really into this tactile experiential thing of playing a record and the people who are into these weirdo stories like Connie Converse. I’m sure you could do a Venn diagram —

Dan: Her music, too, the vibe of her music and the vibe of vinyl is kind of, there’s a crossover —

David: Light a candle.

Dan: So we wanted to please that one person. Or two people.

David: And we thought that it was the right way to present her music, and especially the right way to present what we envisioned as a really special collection of her music.

How many copies were you going to do?

David: We were going to do 300 copies of the special edition, two-LP set, but at the same time we wanted to run 500 copies of the first CD as a vinyl edition.

Dan: Yeah, like a straight reissue. And ultimately, that was too ambitious.

Dan: I used to think that — and this is just speculation — I think of a Kickstarter, I suspect that the more successful a project is, the more successful it will be. If you’re 80% at your goal, then someone who doesn’t really know the project might be more likely to support a project like that.

Right. Like once you get momentum going —

Dan: Whereas something hovering at 10% is less likely.

Kickstarter is such an interesting sort of alternative economy.

We chose to go about it very differently. It was like, “Here’s a story. You may know it already; you may not. And this is what we’d like to do.”

David: There are people who make all kinds of money on all kinds of bizarro stuff. There are some great projects; there was this bike-light project that makes your bicycle look like a bike from Tron. It was $250, and there were thousands of supporters.

Dan: That girl from Pomplamoose raised $120,000. Her goal was $20,000.

David: Pomplamoose?

Dan: They’re this duo, this sort of indie-pop duo. They were in a Hyundai commercial last year. They’ve done Beyoncé covers on YouTube?

David: Ah, yeah yeah yeah.

Dan: I understand her appeal, and I think she’s kind of cool. But it’s just amazing that she made six times her $20,000 goal.

David: I’m really positive on Kickstarter. I think it’s great. I don’t think that the reason we didn’t get funded was the fault of Kickstarter.

So what do you think it was?

Dan: I think part of it was marketing on our behalf, because it was — well, first of all, not a thing about our project had a personal appeal. Whereas a lot of Kickstarter projects I’ve seen are very personal.

David: Like a guy in a video saying, “Blah blah blah.”

Dan: Right, it wasn’t like, “Hi, it’s me! This is what I want to do. Help me!” We chose to go about it very differently. It was like, “Here’s a story. You may know it already; you may not. And this is what we’d like to do.”

David: Also, I think in general the market for music by people who are no longer around to play their music is very different from that of people who are like bands touring or something like that. You know, fans jump in on a different kind of involvement, a different level of involvement.

It seems like today people almost expect to be able to interact with the musicians they like on Twitter and whatever.

Dan: I have friends in bands on Kickstarter that are basically auctioning off dates with the singers of their bands.

David: A date with Connie Converse would be amazing.

Oh, I wanted to talk about — one of the rewards you offered, which was a visit to her apartment. Where is her apartment and how did you find it?

Dan: Well, she had — three?

David: Yeah, she had three addresses in New York.

Dan: She basically was moving from the West Village to Hell’s Kitchen, I think, and then up to Harlem, or Morningside Heights, through the decade.

David: Yeah. Because she sent her songs to the U.S. copyright office. She got copyright on a lot of her songs. And there was a registered address on her copyright.

Oh, so that’s how you found out.

David: Yeah, and that also gave us the chronology of where she was living over a handful of years, maybe five or six years we have those records. We have a record that her landlord sent to the, whatever, the New York City housing office. I think she was paying sixty-some-odd dollars a month for her apartment in the West Village. Which apparently was still a lot of money.

So a visit to her apartment was the closest you could get to offering a date with Connie Converse?

Dan: Right. That was the thinking.

What would you do differently if you were going to do it again?

David: What we would have done and what we are now planning to do is scale it down a lot. Not necessarily in terms of — we don’t want to scale down the quality of the materials, just the scope of the release. We’re doing a smaller run and trying to find some ways to maybe make the book a little smaller, not as many pages in the booklet, maybe print the cover, what’s going to be the folio enclosure in a different way to make it a little less expensive, and try to find partners who will want to do a co-release maybe.

Dan: That’s the thing, too. The money we were asking for was basically for us to produce it entirely ourselves. And so now we’re considering taking partners.

David: I think, maybe naively so, I envisioned Kickstarter as an interesting presales kind of platform, but also, an ask your customers what they want and respond accordingly sort of a thing? Whereas it’s not that businesslike. It’s not set up to be that… Straightforward isn’t the right word —

Transactional?

David: Yeah, transactional, exactly. It’s set up to make you feel like you’re part of a big group of friends.

How did you decide on the name Squirrel Thing for your label?

David: It’s a line from one of her songs.

Why that lyric; why that song?

David: Well, it was one of the first ones that we heard. I mean, “One by One” was the first song that we heard, but “Talkin’ Like You” was a crowd favorite among her friends and family.

David: And it’s so peculiar.

What do you think it means? Is she just talking about an animal that’s like a squirrel in a tree?

Dan: Yeah, yeah. But cheekier, it’s like flippant.

David: The song is also very bubbly and very quintessentially Connie, in the sense that the tone belies the meaning. It has a kind of bouncy thing going on, but it’s really about these two people who love each other but can’t stand each other. It’s sort of a theme going on. The actual “squirrel thing” is, I think, a metaphor that she’s using, or an image that she’s using, that has a lot more than that wrapped up in it. But how many other people would have found something to rhyme with “quarreling” and said, “Ah, yes. Squirrel thing!”

Dan: Yeah, we really liked the image of it, we liked its poetic nature, and we thought it would be fitting to use it as a tribute to Connie.

David: Yeah, we don’t necessarily want to be, like, all Connie Converse, all the time.

Dan: Yeah. We want to do other things.

David: But we don’t necessarily feel the need to do a bajillion projects. At this point, we’ve done a record a year. And that’s maybe not the speed that I’d like to be going ultimately, but it is what it is.

What other kinds of projects do you want to do going forward?

David: Personally, I’d prefer to do the kind of projects that you stumble on, like Connie Converse. Things that would otherwise get forgotten about or tossed aside.

Dan: Yeah, whether it has been overlooked or not, I’m looking for projects that have a compelling story. I think generally we’re looking in the realm of a rerelease.

The untold, forgotten stories.

David: You know, the 21st-century Holy Grail. It’s our version of sailing across the ocean or finding the North Pole.

Was your Kickstarter unsuccessful? Want to talk about it? Send us an email with a link to your Kickstarter page at kickstarted@theawl.com.

L. V. Anderson lives in Brooklyn and works at Slate.

A Possible Cure For The Christmas Song Blues

I was in a CVS last night buying smoked almonds and dental floss — yes, yes, it’s all rather glamorous over here — when “Most Wonderful Time of the Year,” a song which never fails to send me into paroxysms of depression, started playing. I had somehow managed to avoid it thus far, but now I have the Christmas sad. I am going to try to listen to these actually great Christmas songs to cheer myself up, but sometimes it’s just hard.

Pictures Of You From Space (With Bonus Quiz!)

Pictures Of You From Space (With Bonus Quiz!)

Do you ever wonder how many pictures there are with you in the background? Like, the ones taken at crowded bars during other people’s birthdays; or when you stroll through someone else’s shot at a tourist attraction; or when you get good seats at a game? You’re probably in the background of thousands upon thousands of photographs — and you’re probably making a stupid face in every single one of them. On top of this, your picture also is being taken daily in ways you may not be aware of: from 400 miles above, by the satellites used to observe the earth. Lucky for your face, you’re too small to appear, given the resolution capabilities. But you’re still being ‘remotely sensed,’ your house a blip that appears as part of the imagery, in the same way you’re a part of someone else’s photo album.

‘Remote sensing’ is a fancy term for looking at something without actually being near it. Or, as I called my college class on the subject, “looking at stuff from space.” The term encompasses lots of technologies — RADAR, LiDAR, aerial photography, etc. — but today we’re talking about satellites, specifically, imagery and observation satellites. Then let’s see how good you are at recognizing things from space.

This is a first photograph of Earth taken by a satellite. It was captured by Explorer 6 on August 14, 1959. That white smeary thing is an image of Pacific clouds, taken at an angle while the satellite passed over Mexico. As a total coincidence, August 14 1959 is Magic Johnson’s birthday. Can you imagine if he had been in Space Jam? I would have had a connection to make here. Oh, well. (This is just one of the many great missed coincidences in 1959. On the same day the Buffalo Bills were established — Oct. 28 — Lycra was introduced to the world. What if the Bills were a swim team?! The mind reels.)

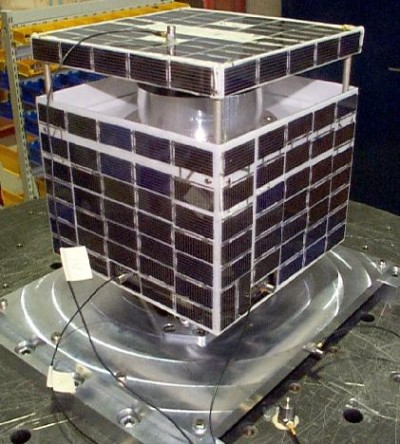

The space race kept imagery technology advancing at an impressive clip. By 1972, the same year the famous Blue Marble photograph was taken by astronauts aboard Apollo 17, NASA was launching the Earth Resources Technology Satellite, later known as the first of the Landsat birds.* There are hundreds of satellites up there, taking images as they pass overhead. India has a team of satellites, Argentina, even Sweden has one.

Some of them, like GOES-8 here, make me want to play air guitar.

Others, like Sweden’s Munin, look like a model of my dad’s office building.

The Landsat program (first run by NASA but transitioned to NOAA control during the Carter administration) has launched six successful satellites into orbit (and one failure into the ocean). The team of satellites have captured millions of images of the earth over nearly 40 years of service, providing a constantly growing, publicly accessible library of the changes taking place across the surface of the planet; it’s an invaluable resource for everything from urban planning to forest monitoring. The two Landsats currently functioning, 5 and 7, have fallen on hard times. Landsat 5 is in a 90-day break imposed this November after a critical component was found to be heavily degraded. But don’t feel too bad for ol’ fivey; it was launched in 1984 and was predicted to last three years. Landsat 5 has functioned for 24 years beyond expectations. Landsat 7, launched in 1999, suffered a failure four years later of the Scan Line Corrector, a component that kept images taken parallel to each other. Though 5 and 7 may sound a little bruised, help is on the way: Landsat 8, the Landsat Data Continuity Mission, is scheduled for a launch in early 2013.

These Landsats, like most imagery satellites, follow a polar orbital path — they circle the earth from pole to pole and back up again, crossing the equator at a different location on each pass — as demonstrated in this animation. The Landsats have a revisit time — that is, the time it takes to cover every image-able surface — of 16 days, but newer satellites have a revisit time as short as two days.

As I said, the Landsats aren’t the only satellites up there. In addition to God knows how many military satellites (have you ever looked at a launch schedule? Stuff is being tossed into space all the time), there are a pair private-sector companies, Digital Globe and GeoEye, operating earth observation satellites. These companies provide extremely high-resolution imagery to many companies, including Google. Next time you’re on Google Earth or Maps, check the credit bar. Most often you’ll see one (or both!) of those names credited at the bottom. In fact, GeoEye’s 2008 launch of GeoEye-1 even carried the Google logo on the side of the rocket, leading many people (who neglected to read whatever text was near photos of the thing) to believe that Google itself was launching a satellite.

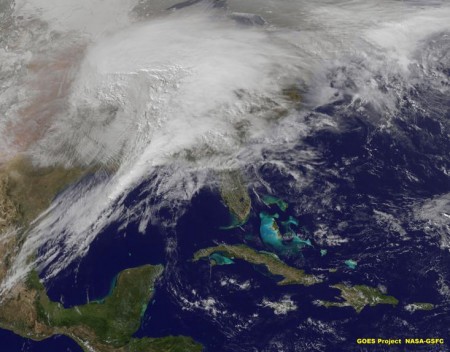

Meanwhile, satellites in a geosynchronous orbit, mostly weather satellites, hover above the same place on the planet, following the earth’s rotation. The United States’ GOES (Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite) and the EU’s Meteosat are both such networks. Among many other uses, the National Hurricane Center uses GOES imagery to track storms during hurricane season. Many of those satellites are not active at the moment, but some birds are designated to update every 30 minutes. You can check them out here. There was actually some big news on the GOES front these past weeks as GOES-11 (the eleventh GOES launched), having faithfully imaged the Pacific as GOES-West since 2000, was decommissioned (see its last photo here, under a truly apocalyptic headline). A decomissioned satellite, by the way, will probably not crash down to earth ROSAT-style. Most are just sent outward in what’s called ‘a graveyard orbit,’ there to float with other decommissioned satellites, assorted debris and space junk.

Now a quiz! Can you name what you’re seeing in these nine images? Answers follow below.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

Answers:

1. Baghdad (satellite image by Landsat)

2. Obama inauguration (satellite image by GeoEye)

3. Hurricane Irene (satellite image by GOES )

4. Eyjafjallajokull Volcano (satellite image by GeoEye )

5. Feb. 1, 2011 East Coast Blizzard (satellite image by GOES )

6. Auckland (satellite image by Landsat)

7. El Capitan (satellite image by GeoEye )

8. St. Louis (satellite image by Landsat)

9. This morning’s view (satellite image by GOES)

* Technical jargon!

Victoria Johnson is a cartographer and this is her Tumblr.

Other images: Explorer VI satellite courtesy of NASA, via Wikipedia; GeoEye launch photo courtesy of GeoEye; GOES-1 graphic courtesy of NOAA Photo Library, via Wikipedia; Munin satellite picture courtesy of its website.

Our Holiday Gift Guide for Extremely Rich People

Christmas is nearly upon us. Are you prepared? Let us help with this guide to gifting for every occasion. All of the gifts here are certified by us as things that people actually would truly like to receive this holiday season. (Hint, hint.)

JUST TRINKETS

Hermes leather coffee cup holder. $195.

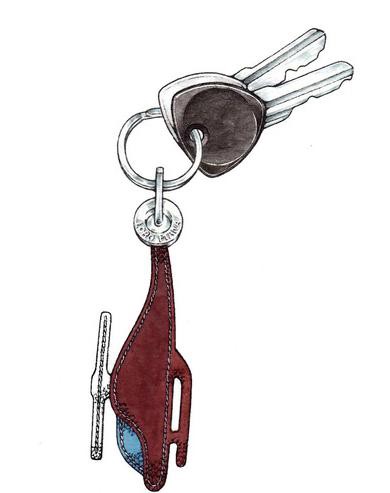

The “My Helicopter” key ring, Loro Piana, $195.

FOR TRAVEL PALS AND VACATION BUDDIES

For ski! The Kjus Hawk insulated jacket. Super-trim, super-slim. $1490.

For her, for the boat: Bottega Veneta Nero Pewter Peridot Sandal (Cruise ‘11). $920.

For him, for the boat: Bottega Veneta Pewter Turquoise Intrecciato Suede Sneaker (Cruise ‘11). $560.

FOR ANIMAL LOVERS

The MacKenzie-Childs Pet Palace. “A royal setting for your prince of a Pekinese or Pomeranian. And a truly extraordinary piece of furniture.” $3500.

Balenciaga neon large dog collar, $295.

The Louis Vuitton Pet Carrier. (N.B. Not approved for use on most commercial airliners; appropriate for private flights.) Circa $2100.

FOR YOUNG FRIENDS

Marc Jacobs Fall ’11 “Garage Denim Pant.” $792.50.

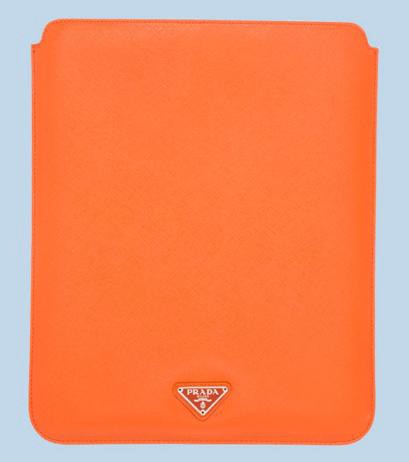

Prada iPad cover (color: “papaya”), in saffiano calf leather, $300.

FOR YOUR HOSTESS

Sharon Core, 1606, edition of 7, initial prints in edition start at $7500.00 and escalate.

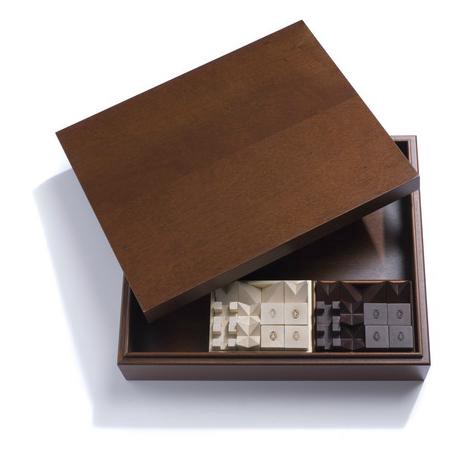

Mahogany chess box and pawns. Loro Piana, $6450.

Jim Hodges, Untitled, metal chain, circa $375,000.

FOR THAT SPECIAL SOMEONE

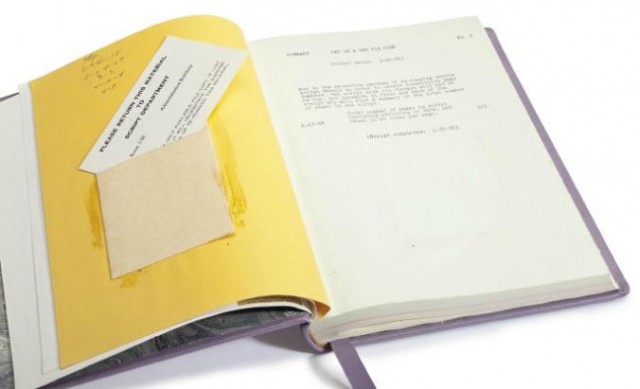

Elizabeth Taylor’s script for Cat On A Hot Tin Roof, bound for her by Eddie Fisher, “with attached leather bookmark gilt-stamped To My Wife — My Life — Love Eddie.” Christies, estimate $3,000 — $5,000, realized price for auction on December 16th surely much higher.

Gaetano Pesce, “Executive Desk for TBWA/Chiat/Day New York, ca. 1994.” Phillips de Pury, estimate $4,000–6,000, on auction December 14th.

Classic 1954 Bell 47G helicopter. $150,000.

5,834 acres in Lewis County, Washington, $10,979,000.

New Magnetic Fields Album, With Synths. Synths!

“After putting out their ‘synth-free trilogy,’ The Magnetic Fields are returning to their signature mix of synth and acoustic sounds. Merritt notes about the new album that ‘instead of using a synthesizer as a melodic instrument, much of the time I used it as a compositional destructive mechanism, something eating away at the apparent order of my perfectionist arrangements. I was very happy to be using synthesizers in ways that I had not done before. Most of the synthesizers on the record didn’t exist when we were last using synthesizers.’ The songs — none over three minutes long — were recorded with Merritt’s usual cast of collaborators: Claudia Gonson, Sam Davol, John Woo, Shirley Simms, Johny Blood and Daniel Handler.”

— Oh, man, now I’ve got to stay alive until March, when The Magnetic Fields release Love at the Bottom of the Sea

, their new album.