And We're Back

Happy New Year and welcome back! On the off chance that you missed our series about milestones — and, hopefully, you were able to stay away from the Internet for the whole week — here’s what you should print out and read once you’re caught up with “work”: “Trinity,” by Maria Bustillos; “20 Years After Achtung Baby,” by Elmo Keep; “Each Generation Has Found They’ve Got Their Own Kind of Sound,” by Daniel D’Addario; “Playgirl’s First Hardon,” by Jessanne Collins; “Some New Directions,” by Thomas Beller; “Poses,” by Rakesh Satyal; “The Day the Gold Disappeared,” by Carl Hegelman; “You’ve Been Shot,” by Erik Martz; and “Brooklyn’s Return,” by Brent Cox. Anyway, it’s to 2012! Let’s all pretend it’s gonna be better than last year. Also, how were your holiday festivities? Tell us in the etc.!

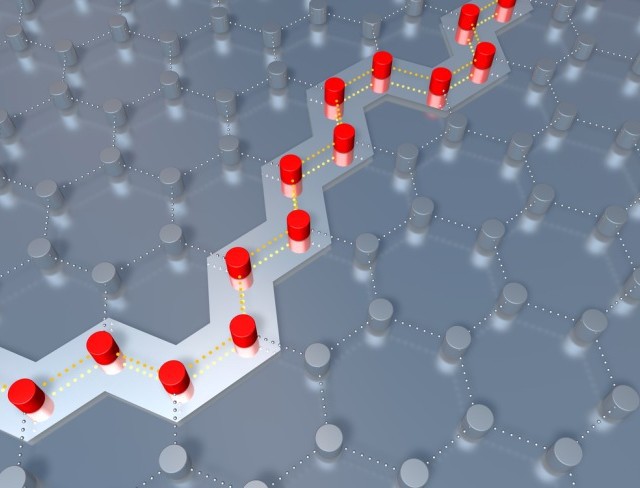

Photo by JNT Visual, via Shutterstock

I Have Thoughts About Commenting Systems!

Hello, and welcome. If you’re here, it’s because you have something to say about commenting at this site, about changes to commenting, or related matters. Let it fly! And thanks.

Brooklyn's Return

Shut up about Brooklyn already. We all know about Brooklyn, that shining city on the hill, where everything is made only of awesome. Yes, there are beards and clunky eyeglass frames and lawyers who skateboard and grandpas with noise bands. The hipsters run-off freely now, the cheesecake is largely appareled American and vice now has a market cap. There’s even a successful sitcom that purports to be set there, which is as large a cultural signifier as anything — Brooklyn may be located on the western-most tip of Long Island, but where it actually lives is dead solid in the middle of the zeitgeist. It’s now, it’s hip, it’s hot, it’s happening. There is no mystery of Brooklyn to it. And this is why shut up about Brooklyn already.

Part of what put Brooklyn over the top where it is now — both beloved and reviled, a migration target and the butt of jokes — involved a fat shirtless guy being knocked out of his shoes, in front of not so many people.

Brooklyn is back to where it was in the middle of the 20th Century: the capturer of imagination. Back then, the awesome was equivalent but in different flavors. The Dodgers played in Flatbush, the longshoremen looked like Marlon Brando and that burly Brooklyn squonk of an accent was not just uniform in the borough but popular among the entertainers of the day. Back then, Brooklyn served the purpose that Canada does today.

But this was not always the case, there in Brooklyn. There was a time in between these two times when the crime rose and the neighborhoods unsettled. There was a time when all Brooklyn had going for it was the opening credits of “Welcome Back Kotter”, when it was living not only in the shadow of Manhattan, but also of its former glories, and this time stretched right up to the turn of the century.

This is not meant to be a travel brochure for Brooklyn: yes, I live there, and I have done so for coming on twenty years, but I assume that anyone that lives in the same place for so long will have similar sentiments. But I’ve been there (or let’s just start saying, here), both in times of ignominious squalor and generally bad borough-reputation (which were more fun than you’d think) and in times of the Bright Shiny Animal-Hat Wearing Brooklyn. Plus also, that transitional moment? I was there.

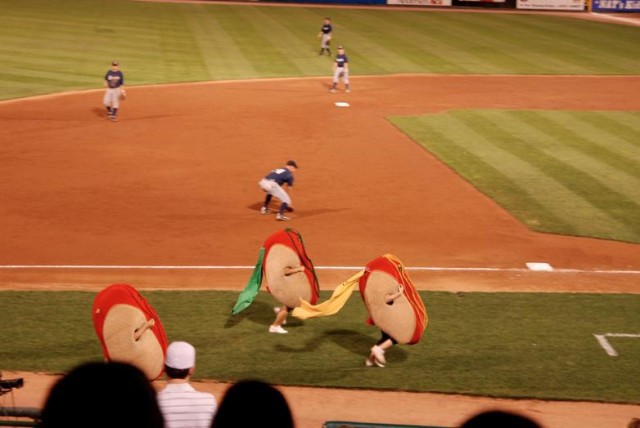

In 2001, baseball returned to Brooklyn. In Coney Island, a modest little stadium was built, and the Cyclones brought pro baseball back for the first time in 44 years. My friends and I were very excited by this, having lived in Brooklyn for a while, and we obtained a nine game season package.

They were a Single-A short season club for the New York Mets, which meant that the players were largely fresh out of the draft, and generally either starting a long road to the bigs or enjoying their brief stay as the talent was winnowed out. It also meant that there was no such thing as a routine throw to first. But the games were fun, sitting in that park hard on the beach and the Atlantic Ocean behind it, the actually Cyclone visible (and audible) in the distance over the left field fence. In the stands, the atmosphere was festive, old-timers and hipsters alike keeping the taunting PG for the masses of kids there, a fellow named Party Marty running the mid-inning promotions (like “Who Wants A Pizza?” and “What’s In The Box?”), and characters attending every game, like this old fellow who looked like he might have been an original extra in “Saturday Night Fever” who boogied in the aisle holding a sign that read “DISCO MANIAC” (though we called him the ESCAPED DISCO LUNATIC). Basically, the Ur-baseball experience, without the complications of drunken fans working blue, or actually caring about the outcome of the season.

On June 26 of 2001, we got to see our first game, the second home game for the Cyclones ever, and the atmosphere was as described above but after a heroic dose of Dexadrine. The people that could remember the last Dodger’s game in Ebbets Field were nearly in tears for the day, and the little kids were feeding off that and were spider monkey to an extra degree. It was packed to the rafters (what few rafters the place had). It was a big day for Brooklyn. We all felt prosperous and lucky, and the future was as unfathomably big as the ocean stretching out past Sandy Hook and to the vanishing point.

I don’t remember who the Cyclones played or what the score was, but I do remember this: somewhere in the middle innings, between pitches, a man jumped onto the field and started to run around. Usually this behavior is tolerated by the crowd for the spectacle, but on this day we were not in the mood: the dude, an older guy, large, flabby and without a shirt, was almost immediately booed. But the security staff, two days into the job, must not have been particularly skilled at their jobs, because they were unable to catch the fat shirtless guy, stumbling after him in lazy circles in shallow right field.

Once the fat shirtless guy realized that he wasn’t getting tackled immediately, he did what every unauthorized field runner does — he decided to round the bases. The other team was in the middle of their at-bats, so the Cyclones were in the field. The infielders all stood well off the bags, with their arms crossed. They were not going to take part in this foolishness. And so the fat shirtless guy made his slow procession, first, second, with hapless security far behind.

Except for the catcher, that is. The catcher, Mike Jacobs, a righty from Chula Vista, California, stood astride home plate. The fat shirtless guy was rounding third. Mike Jacobs didn’t budge. And as the fat shirtless guy approached home, unsure whether to slide or not, Mike Jacobs speared him: basically picked him up and drove him into the dirt.

The stadium exploded. We roared because the fat shirtless guy was done and baseball would recommence, and we roared because our catcher was so dedicated as to protect that plate under all circumstances: from fat shirtless guys, from seagulls, from the wind and the rain. But we also cheered because we were Brooklyn, and many of us were feeling that we were Brooklyn for the first time.

Oddly, I seem to have a knack for being present at auspicious New York baseball moments, even though I only catch a couple games a year. I was at the old Yankee Stadium when David Wells lumbered through a perfect game in 1998, and the only Major League game I saw was in the new Yankee Stadium, when Derek Jeter hit his 3,000th hit (and four others). I am apparently good luck for someone (though sadly that someone is the Bronx Bombers).

But that moment, Mike Jacobs leveling the fat shirtless guy, was the sweetest moment of all. Brooklyn was well on its way up at that time — galleries were opening in Williamsburg, a modest restaurant row was popping up on Smith Street in Carroll Gardens, and other neighborhoods like Red Hook and Kensington were being chosen by the students and the refugees from Manhattan not just for the rent but for the fabric of the neighborhoods, decades old. That game was a big Brooklyn appreciation party, attended by both the new and the old Brooklynites, and during this party a recent transplant from California defended the Brooklyn institution of baseball from the depredations of the fat shirtless guy.

Mike Jacobs was eventually moved to first base and ended up with four years in the Major Leagues, with the Marlins, Royals and the Mets and then, well, like so many of us, he took a few shortcuts. And Brooklyn? Well, Brooklyn is a movie star now. It’s a phenomenon with which you are no doubt familiar, and one regarding which you are likely sick to death.

Brent Cox is all over the Internet.Photo by Pete Jelliffe.

Football Pick Haikus For Week 17

January 1

At Philadelphia -8.5 Washington

The bad dream’s over

in Philadelphia.

Fire Andy Reid!

PICK: EAGLES

At Atlanta -11.5 Tampa Bay

I wish they’d open

a Waffle House for us in

Brooklyn, NYC.

PICK: BUCCANEERS

San Francisco -10.5 At St. Louis

Rams will probably

fire Coach Spagnuolo and

the Giants will hire him.

PICK: RAMS

At Minnesota -1 Chicago

Can a team without

a running back beat a team

with no QB? No.

PICK: BEARS

Detroit -3.5 At Green Bay

Lions can send a

big message that they’re for real.

Pack lets ball boys play.

PICK: LIONS

At New Orleans -8 Carolina

In the battle twixt

Kitties and the Do-Gooders

Cam Newton scores big.

PICK: PANTHERS

Tennessee -3 At Houston

Texans say they won’t

bench their third string QB for

this game, FYI.

PICK: TITANS

At Jacksonville -3.5 Indianapolis

If the Colts win this

game they will rue it for a

sad generation.

PICK: JAGUARS

At Miami -2.5 NY Jets

The Jets are clearly

the greatest 8–7 team

in league history.

PICK: DOLPHINS

At New England -11 Buffalo

Patriots play hard

in first half then let Gisele

Brady play QB.

PICK: PATRIOTS

Baltimore -2.5 At Cincinnati

Bengals having to

beg their fans to show up to

games is just so sad.

PICK: BENGALS

Pittsburgh -7 At Cleveland

Even if Steelers

stayed at their hotel they’d beat

this fucking game’s spread.

PICK: STEELERS

At Oakland -3 San Diego

Bay Area fans

can turn the page and enjoy

Warrior losses.

PICK: CHARGERS

At Denver -3.5 Kansas City

Can Tim Tebow get

to the football promised land?

Well, yeah, most likely.

PICK: BRONCOS

At Arizona -3 Seattle

I enjoy Starbucks

and Nirvana and Pearl Jam

and Bridget Fonda.

PICK: SEAHAWKS

At NY Giants -3 Dallas

There’s no way that the

Giants can win this game but

poor Romo is jinxed.

PICK: GIANTS

Last week Haiku Picks Went 11–5. That makes it 117–121–6 for 2011. One week, one shot at .500! Playoff haikus? If you demand ‘em!

Jim Behrle tweets at @behrle for your possible amusement.

You've Been Shot

by Erik Martz

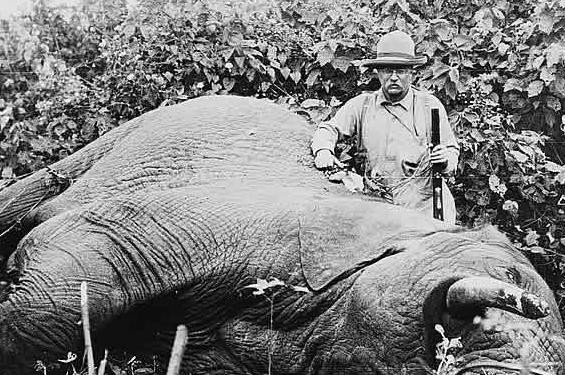

In October of 1912, Theodore Roosevelt was about to give a speech in Milwaukee in support of his reelection campaign under the newly created Progressive “Bull Moose” Party when a bartender named John Flammang Schrank walked up and shot him in the chest. Roosevelt of course was not killed, but neither his survival nor Schrank’s claim that he was instructed by the ghost of William McKinley to prevent a third term for the two-term former president were the most extraordinary parts of the whole affair. It was the fact that Roosevelt decided to deliver his speech in the Milwaukee Auditorium anyway, for an hour and a half, with blood seeping through his clothes. “Friends, I shall ask you to be as quiet as possible,” he began, “I don’t know whether you fully understand that I have just been shot; but it takes more than that to kill a Bull Moose.”

Reading a transcript of the speech is probably more comical than it should be, or than it would have been at the time. Having concluded from the fact that he wasn’t dead that the bullet had not penetrated any vital organs, Roosevelt spent the better part of the first half of his prepared remarks assuring the alarmed crowd and the various dignitaries and medical personnel pleading with him to leave the stage that he was not dying and in fact not much affected by the bullet wound. “Don’t pity me,” he said, “I am all right. I am all right, and you cannot escape listening to the speech either.”

The character named Teddy Roosevelt — the blustering, mustachioed bull moose caricature that posterity has given us — tends to shine through here. Only Teddy Bear the Rough Rider, the red-blooded man’s man, would have endured a gunshot wound to deliver a speech in which he somehow tied the attempt on his life to the Taft/Wilson Republican regime’s attempt to disavow worker’s rights and assassinate the former president’s character. Only the notoriously long-winded Teddy Bear would have been saved from death partially by the thickness of his speech manuscript, which was folded into his jacket pocket over his right breast where the bullet struck him. Only Teddy Bear, fiery activist and intimidating orator, would never let a bullet’s progress inhibit the chance for real social progress.

The image is a dream, of course, but it’s always been a compelling one, more so now because one can hardly imagine such a person existing, or such a thing occurring, in modern politics. There are no Roosevelts in either the Republican or Democratic party of today, even among those who invoke him. Such booming candor would hardly be appreciated on the eggshell-laced floors of Congress, where integrity has been been traded out the market door like so much speculation on rotting fish. Is there a man or woman in our assembly of politics who one could see standing next to Teddy on that platform, crippled from relentless attack, but spurred on by the sheer volume of their ideas and their will to push the country forward? Gabrielle Giffords comes to mind, but her story has already been wrapped, neatly bowed, and forgotten at the department of public inattention.

Everyone plays the game the same old way, not applying the lessons of history, but admiring them in a china display of fragile, pretty ornaments to be used when campaign funds dry up. Yet in the back of the cupboard on some glazed filigree of the past, a scene is illuminated in which a bespectacled man reads out to a gathered assembly of concerned American laborers a plan for labor rights and fair economic play, in the state where almost a century later, concerned laborers would again gather in protest against the belligerence of Republican authority — the authority which the bespectacled man had abandoned a century earlier for a now oxymoronic progressive-conservative tandem agenda.

Roosevelt excoriated the party which he had abandoned, and which he felt had abandoned him. “But while they don’t like me,” he said, “they dread you. You are the people they dread. They dread the people themselves, and those bosses and the big special interests behind them made up their mind that they would rather see the Republican party wrecked than see it come under the control of the people themselves.” He probably didn’t even need the bullet-shattered notes in his bloodied coat pocket. The bull had steam, and the hunt was on. “There are only two ways you can vote this year,” he said. “You can be progressive or reactionary. Whether you vote Republican or Democratic, it does not make a difference, you are voting reactionary.”

The cycles of economic crisis precipitated by political ineptitude, followed by the typical blind swing at the nothing of reactionary politics, are well chronicled, to the point that we can look into the reflection of “I have just been shot” and witness the faint outline of our own moment a century later. Republicans, it turns out, haven’t changed that much. The Perrys and Romneys might as well be the Tafts and Wilsons, as beholden to oil and other special interests near the end of their influence as their predecessors were at the beginning (Perry in particular is a bath tub away from infamy). Their voices are interchangeable, monotone, and more those of David and Charles Koch than the otherwise well-meaning Tea Party stooges, who unwittingly voted more money out of their own bank accounts and into those of the wealthiest because they were scared into believing that “progressive,” a word that essentially describes the course of human events that led to their existence, is wrong. In response to this insult, the Democrats have once again disappeared to wherever it is they go, leaving a would-be progressive president to weather a reactionary battery of frantically backward-receding minds (think not of 1912, but of 912). Meanwhile, as winter comes on, Occupy Wall Street, a genuinely progressive movement, struggles with how to proceed or communicate its complaints against a conservative business class whose impaired empathy and endemic contempt for the poor have finally been stripped naked in the public square.

All around us in politics and business, we witness the reactionary — the dread by those in power that the people of this country might not actually like things as they stand. This is as it should be. But where is the voice of reason, haggard from wounding, that nevertheless rings out? Roosevelt the Republican was no perfect president. His jingoistic bravado and imperialistic tendencies softened the bite of his more democratic beliefs. For all his trust-busting, he was at base a conservative with a mind toward expanding American commerce by any means necessary. Likewise, though he loved nature, his enthusiasm was somewhat undercut by his penchant for hunting endangered species.

Still, it was his belief in commerce that pushed him to improve the lot of the average American. It was that same zeal that caused him, an environmentalist Republican, to take the advice of noted hippie scientist John Muir in the matter of conserving natural resources and preserving national park lands. It was Bull Moose Teddy who finally broke away from the establishment, pushing the phantom third party platform that still has no foothold to this day, campaigning tirelessly for the “square deal” he planned to make with all Americans. And then he was shot.

Many of us have been shot, too, many, many times, again and again, in the same exact place. But like Roosevelt, we stagger to our feet after each blow, mindful that we are still alive, though the wound gapes ever wider. Our own speeches have changed over the years, shrunken down now to fit the economy of social media and the various factions which claim pieces of it. One version says, “We are the 99%,” while another cries, “Don’t tread on me.” One’s enemy is big business, the other’s is government. Both decry corruption. Our collective sighing is the echo of one weakened voice nevertheless booming out over the heads of a Milwaukee crowd 99 years ago. “I do not care a rap about being shot,” it says, “not a rap.” Let the hunt begin.

Erik Martz is a writer living in Minnesota, where a famous president once implored state fair attendees to “speak softly and carry a deep-fried candy bar on a stick.”

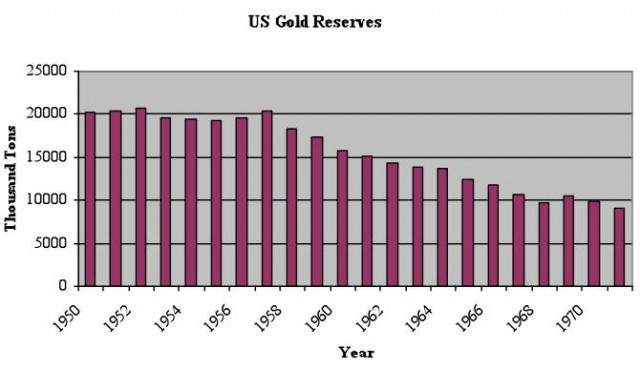

The Day the Gold Disappeared

by Carl Hegelman

In the long summer vacation of 1971, I “worked” on a construction site in the English countryside where they were proposing to build a new hangar for the U.S. Air Force, and used the proceeds to take a holiday in Greece with my friend Charles. Originally, the idea had been to hitchhike, having crossed the channel on the boat and made our way from Calais to Paris by bus. We soon found out what I had been warned of, that the French can’t abide hitchhikers. After sleeping in the Bois de Boulogne we fluked a short ride to a small town by the name of Auxerre, and there our luck ran out. We stood by the side of the road and for the rest of the day stuck out our thumbs in vain. There was a storm that night, the worst they had suffered for many years, and, abandoning the woods, we laid down our dampened sleeping bags on a narrow strip of shelter by the pumps under a gas station canopy which rang all night with the fusillade of golf-ball sized hailstones. Having stood by the side of the same road for most of the next day, we got tired of looking up Gallic nostrils and spent some precious money on train tickets to Dijon (in the south, named after the mustard). Amazingly, even after dark, we got a lift from the eastern outskirts with some clergymen — they were Belgian, not French — stayed the night for free at their monastery in the mountains, and arrived in Lausanne the next day full of warm feelings for les Belges. The Swiss, too, were much less snooty than the French, and it took no more than a couple of hours to get to the border town of Brig, where we were picked up from the Shell station at the foot of the nearby Alp by a truculent Italian workman in a Fiat, who drove us to Bologna without a word. And that’s when Richard Nixon stepped in. He decided to take the U.S. dollar off the gold standard, and as a result, for a couple of days, nobody would change any money. All you could get in the cambio for your travellers’ cheques or your leftover francs were Italian shrugs.

If you’d asked me at the time why the bureaux de change had shut down, I’d have had absolutely no clue, nor did I spend any time wondering about it as we wandered, hungry, about various piazze looking for somewhere to get lire. The fact that my holiday had been financed by the U.S. Air Force didn’t occur to me as being in any way related. But the “Nixon Shokku”, as the Japanese called it, was a historic event. It marked the end of the Bretton Woods international currency system put in place by a passel of politicians and economists at a conference in New Hampshire some 27 years before, in 1944.

The idea of Bretton Woods was to create stable exchange rates to facilitate international trade and forestall the competitive devaluations that had helped destroy it in the 1930s. The way they did it was to fix the dollar to gold (at $35 per ounce) and fix all the other currencies against the dollar, so anyone wanting to do business with another country would know how much it was going to cost him. If you were a foreign central bank, you could, if you wanted, convert your dollars into gold, so really every major currency was indirectly tied to gold. The U.S. at that time owned about 65% of the world’s gold reserves, and was required by the Federal Reserve Act to allow no more than four times that amount in circulating dollars. Most of the dollars, obviously, were owned by Americans, and Americans weren’t allowed to convert their dollars into gold — in fact, it had been illegal since 1933 for Americans even to own gold other than in jewelry or numismatic coins. So nobody had much doubt that if he wanted gold instead of dollars the U.S. was good for it, and so nobody really bothered converting their dollars to the less convenient gold. Bretton Woods also created the IMF, whose job was basically to make sure the member countries didn’t endanger their exchange rates by irresponsible spending — a sort of international “fiscal union” much like what they’ve been talking about recently in Europe.

As proprietor and printer of the world’s reserve currency, the U.S. wasn’t behindhand in spreading it abroad. There was the $13bn Marshall Plan, which, together with $12bn in previous aid, revived Europe and so created markets for U.S. goods. (This may not sound like much now, but bear in mind, U.S. GDP at the time was between $220bn and $270bn, and the entire Federal budget in 1948 was about $30bn.)

Then there was a lot of spending on military bases and a flood of foreign investment by U.S. corporations building up their international operations. Still, people didn’t really start to worry until the late 1950s. Beginning in 1959, there was a distinct tendency for the foreign central banks, suspecting the dollar was overvalued, to show up at the “gold window” and demand gold for their increasing piles of dollars. Vietnam and the Great Society programs didn’t help: The Federal budget more than doubled from 1960 to 1970. The amount of freshly minted dollars grew so much that, in 1968, Congress had to repeal the law restricting circulating dollars to four times the gold reserves, allowing the U.S. Treasury to keep printing. Which, of course, worried the foreign central banks even more. When foreign finance ministers whined about the growing level of dollar-induced inflation, Nixon’s Treasury Secretary, John Connally, famously told them the dollar “may be our currency but it’s your problem.” (Yes, the same Connally who got shot in JFK’s Dallas motorcade. By some accounts, he was also, indirectly, indispensable to the election 30 years later of George W. Bush.) Not surprisingly, the foreign central banks kept coming. By 1971, U.S. gold reserves were down from 65% of world reserves to 25%. Nixon was facing re-election in 1972 with unemployment and inflation at vote-squashing levels, and the overvaluation of the dollar tied to gold — though it had been an immense boon to U.S. corporations by enabling them to buy foreign assets on the cheap — was crimping his ability to stimulate the domestic economy.

And so it all snapped that August. Allegedly, it was triggered by a British request to reactivate the Fed’s swap lines and cover hundreds of millions of dollars they had absorbed in keeping the markets orderly. These swaps were essentially a guarantee against loss due to dollar devaluation and had been used for years to prevent too much depletion of the US gold reserves.

Connally, however, told Nixon it was a request for $3bn in gold — about a quarter of the remaining U.S. reserves — a story repeated by Nixon in his memoirs. “All Connally had to hear was that some limey wanted gold,” according to Charles Coombs, a New York Federal Reserve official, and his mind was made up. Connally persuaded Nixon to default on Bretton Woods and put the blame on “an assault by international speculators” — the European and Japanese. They didn’t even tell the Chairman of the New York Federal Reserve. And certainly not the fiscal police, aka the IMF. For good measure, Nixon also imposed a 10% surcharge on imports. Politically and economically, the default and attendant measures turned out to be a brilliant move.

No wonder there was deadlock in the cambio. Suddenly, nobody knew what the exchange rates should be. How many lire for your French francs? Shrug. We were a little weary of hitchhiking by this time, stuck in Bologna on a rainy Sunday evening with too much baggage, no map, no phrase book, not a word of Italian and no clue how to find the road south to Brindisi, where you could catch a ferry across to Corfu and Greece. Fortunately, Charles, who was a worried, conscientious sort of bloke, had taken the precaution of buying some lire before we set off from London. It wasn’t much, but enough to get us on a decrepit wooden-benched train as far as Bari, about sixty miles short. Bari, across the Adriatic from our goal, turned out to be an exceptionally desolate, parched little seaside town, with oil storage tanks and threatening-looking yobs in tight trousers. We spent our last few lire, after sweatily debating in the August sun, on a delicious-looking iced drink which turned out to be all but undrinkable. (All flash, these Italians, Charles decided). Fortunately, the Nixon shock soon passed, the money-changers became more affable, and, a few spaghetti bologneses later, we found ourselves in Athens, camping on the roof of the Hotel Sans Rival. It was mobbed with fellow travellers attracted, like us, by the price — about 5p (roughly 11 cents) a night¹, as I recall. You could share a room for about 25p, but only Americans could afford that, and the roof was wall-to-wall sleeping bags and European longhairs, transients en routeto and from the islands via the port at Piraeus.

All in all, it wasn’t a great trip. We got stuck in a lift for an hour in Athens in the middle of a blazing heatwave. On the ferry over to Mykonos, someone on the deck above puked on my head and there was nowhere to wash my then-copious hair. I didn’t even meet any girls, let alone find a Shirley Valentine type romance. For a ridiculous technical reason, few of the photographs I took with my prized 35mm Voigtländer rangefinder came out. Really, overall, a bit of a bust.

Forty years on, with Greece and Italy threatening to throw the international banking system into fresh turmoil, there is some added resonance to this little episode. The Greeks now owe a lot of Euros which they have no means to pay. A lot of that debt is held by Greek banks, which means that those banks are effectively bust. The Greeks themselves are very sensibly withdrawing Euros from their accounts, which puts those banks in a very tight spot. Quite a lot of the Greek debt is owned by German and French banks, so their ability to lend is severely curtailed, exacerbating an ongoing credit crunch which will undoubtedly provoke a recession in Europe next year. Then there’s the problem of the Credit Default Swaps (CDSs), which are essentially guarantees of the Greek debt. Nobody seems to know who undertook those guarantees (AIG? Goldman?) or how much is outstanding, but if the Greeks default (and there’s a very indignant debate about what “default” means here) they’ll be on the hook for the difference between the actual value of the Greek debt and its face value. The shakiness of the German and French banks, together with the CDS threat, may in turn endanger the US banks. (You can play this by buying one of the short financial ETFs, like SKF, with the risk that they might default too.) And then there’s the possibility that the same thing will happen to Italy and Spain, whose debt is much more ginormous than the paltry Greek debt. The debacle has already claimed one U.S. victim — Jon Corzine’s MF Global, which had $11.5 billion of Italian, Spanish, Belgian, Portuguese and Irish debt (hedged down by some unfortunate counterparty to $6.4bn) — with knock-on effects to its lenders.

Angela Merkel, the German premier, must surely see an opportunity here to put Germany, de facto, at the head of a fiscally integrated European Union with legal authority by treaty over all Euro country budgets. The Brits threw a spanner in those works with their recent veto of the proposed treaty. Nicolas Sarkozy, in France, is wary of full fiscal union, perhaps because France might become its victim if its credit rating is cut, but would still like the EU to have enough clout to make sure the Greeks pay the French banks what they owe. The European Central Bank, which is like the Fed only without the accompanying ability to control national budgets, is ostensibly refusing to come to the rescue by being a lender of last resort. (Except maybe through a back door: its wily new chief, Mario Draghi, is, after all, a former managing director at Goldman Sachs). The Europeans are left with a relatively small “stability fund” (joke!) and our old friend the IMF.

The Greeks have an overvalued currency but no ability to become more competitive through devaluation, except by abandoning the Euro, which would leave them just as poor but without any of the huge advantages of sharing a common currency. (Imagine a United States where you had to change currency, at some unpredictable rate, every time you transacted across state lines). The fiscal police, which in this case means the various European financial authorities as well as the IMF, are only willing to bail them out if everybody tightens their belts. The Greek government, without getting any definitive consent from the Greeks, has agreed to sell off the country — or at least much of its transportation, utility, energy, telecomm, gaming and real estate assets — to foreign (read German/American?) interests in order to help pay their debts.

In short, the Greeks are kind of in the same spot as the U.S. was in 1971, only without the massive economic clout which forces everybody else to forgive them.

But you might as well be poor in Euros as poor in New Drachmas. Even if the EU throws them out, there’s nothing to stop the man in the street using Euros, or, pace Gresham, having dual currencies (like, say, Zimbabwe). Putting myself in the shoes of the average Greek, I’d be inclined to do what Nixon did: Default and everybody can go to hell.

¹ By my calculation, adjusted for inflation that would be about 57p today, or around 60 to 90 cents, depending on how you do it.

Carl Hegelman (a pen name) is a corporate bond analyst and a connoisseur of leisure.

'Poses'

by Rakesh Satyal

Wherever you went in 2011, you could hear Adele’s 21 catapulted at you from every open car window, open apartment window, and open mouth. That album has its charms, but I see a much more long-lasting and powerful influence in Rufus Wainwright’s Poses, and its tenth anniversary has passed without appropriate fanfare.

It was the oddity of the singer’s name and his striking picture that enticed me to buy his first CD with not even a minute between first look and printed receipt. What I heard when I popped the CD into my stereo was astounding and peculiar, a heady mixture of Jon Brion-produced clangs and strums and insistent beats. But most of all, there was that voice, a robust croon that was somewhere between two Kings — Nat Cole and Carole. I had seldom heard such a distinctive tone, deployed by someone whose music was, as many critics attested, a worthy heir to that of the Tin Pan Alley era.

That debut effort, though thrilling and highly ambitious, was merely an aperitif to the gorgeous album that would follow. Poses somehow manages to portray exactly the kind of disillusionment — born from an air of glamorous emotional detachment — that embodied New York in the summer of 2001. Beautifully enough, it did not lose its relevance afterwards; it still shows how the landscape of one’s romantic devastation persists despite all larger events. Knowing the potentially superficial tendencies of his concerns, Wainwright nevertheless finds fair weight in them, making songs that read specific and universal at the same time. Yes, it is very much about Rufus Wainwright, troubadour and gay man-about-town, but it captures the milieu of New York at that time with the utmost breadth and accuracy.

The summer of 2001 was, after all, most surely a Rufus Summer. Not only had Poses come out, but, in an inspired pairing, Wainwright had taken part in the most flamboyant melee of the season, Moulin Rouge! On that film’s soundtrack, he sang a plain but beautiful rendition of “Compliante de la Butte” (a song that, Wainwright himself noted, often became misunderstood as “Complaint of the Butt”). That summer, it felt like every gay boy in the city had a Rufus crush. He had become our pied piper, the boy who could appear in a variety of gay venues and hold court at them all. Britney was still dancing up a storm, and the height of J. Lo’s reign was imminent, but it was more comforting to see one of our own get up on stage with a piano and a guitar — and an unapologetic queeniness — and rack up the accolades.

I bought a ticket that summer to see him open for Roxy Music at the Theater at Madison Square Garden. There I was, dorkily waiting in the lobby to have Rufus sign a T-shirt for me. When he spoke, I felt like I was still an adolescent, back home in my bedroom with posters on my walls and my mom cooking dinner downstairs. (This feeling would be multiplied ten-fold that fall when, miraculously enough, Wainwright visited my college campus and I got to interview him at-length for our school paper. Rarely have I felt like so dithering an idiot.) He had adopted a signature look by then, which usually involved a flowing shirt and tight pants and an inspired collection of accessories, and against the leather pants and spiked hair and punked-out style of the Brian Eno devotees at the show, his persona still managed to stun. “Who,” I thought, in a turn of mind that occurs with the most besotted of admirers, “could wrong a person like this? Who could possibly break Rufus’s heart?” The sprawling “Evil Angel,” in which Wainwright recounts an aborted tryst with a lover who promptly disappears, seemed especially cruel. It seemed clear to me that anyone capable of treating him in such a manner was malignant indeed. The same sentiment defines “The Tower of Learning,” a wonderfully modulated piece of music that builds and builds until it practically shatters with longing and the disappointment of unrealized love.

Still a great deal of the allure of Poses derives not from what others to do Wainwright but what he does to himself. The album — and this would be true of the albums to follow it — is quick to admit that the person who breaks Wainwright’s heart is often Wainwright himself. In it he confesses to a fair share of hedonism and masochism; “cigarettes and chocolate milk” are not foisted upon Wainwright, but are willfully chosen by him. The title track continually trains its blame on the singer himself; he is his own cautionary tale. This was, self-reportedly, a time of much wanton drug use for Wainwright — he had written the album while staying in the Chelsea Hotel, so — and the album is the firmest craft of a poete maudit. (When Wainwright recasts the chorus of “Rebel Prince” in French, late in the song, he might as well be inscribing his name and a date on a copy of Rimbaud’s collected poems.)

One of the album’s most poignant moments occurs when Wainwright covers “One-Man Guy,” written by his father, Loudon Wainwright III. A brilliant (if borderline misanthropic) ode to living by one’s own rules and habits, it is remarkable not only for the way in which the younger Wainwright flips its sexuality for comedic effect but for the bookend it seems to create: here is a perfectly written song, via pere, that foreshadows all that is possible from Wainwright fils. When the tenderly rendered “In a Graveyard” follows suit a couple of tracks later, we yet again understand the surety with which the younger writer takes inspiration from the older. It is similarly rich yet reserved, and as with many songs on the album, it deals with mortality and other weighty matters so smartly that it reinforces the album’s status as a tool of catharsis and confession.

Take, for example, the deceptively buoyant “California.” Although Wainwright’s songwriting ability has been compared to that of Joni Mitchell, this song is decidedly the opposite, in spirit, to her song of the same title. The Sunshine State, in Wainwright’s view, is hardly “home” but a freon-fueled mess hall of vapid, self-conscious poseurs (sure). There’s hardly a more damning conclusion than “Life is the longest death in California,” but what a deliciously delivered pronouncement it is: Wainwright’s specialty is the beautiful pain behind the bruise. The song’s gift lies less in its misery than in the insidious glee of its tune. If New York brings out the brooding sweep of Wainwright’s voice and lyricism, then California shellacs his melancholy and shoves it out with a bright fuck-you.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KtuyzOxTfs8

There is the lovely but anxious movement of “Greek Song” (“I’m scared to death,” Wainwright proclaims), the percussive and insistent thrum of “Shadows,” the courtly love of “The Consort,” one of the album’s calmer moments. But the album’s title song is its most masterful and it captures from head to toe the self-absorption mixed with self-criticism that was the style among gay men at the time. It was the kind of song that you would play to yourself after stumbling home from Beige, the long-running gay party that finally met its end earlier this year: a gaggle of suited-and-booted, roving-eyed, antsy-yet-effete gays who could easily fit Wainwright’s profile of having no more grave matter than “comparing our new brand-name black sunglasses.” (Cole Porter comparisons abounded at this stage in Wainwright’s career, and this is a song quite worthy of them, as heartbreaking, aching and needy as Kiss Me, Kate’s “So in Love.”) It has a measured rhythm paired with lyrics as world-weary and contrite as they are tender. The song is sung as an apostrophe — “You said watch my head about it,” Wainwright sighs over each chorus — and the unidentified “you” of the song could, it seems, be a variety of people or things: friends, lovers, New York, desire, identity. The most touching moment occurs when Wainwright sings:, “Now no longer boyish / Made me a man / But who cares what that is.” I would have a hard time naming one of my gay friends who has not felt this interior struggle, this desire to slough off the demands of being a “strong man” while accepting his sexuality. At the same time, it does not capture only a queer sensibility. It is a song that could apply to many a fledgling New Yorker, struggling to reconcile superficial concerns with much deeper ones.

During that luxurious summer of 2001 — a far funner recession than the one preceding it and following it — the City teemed with a range of sexual options and experiences, and with that freedom came the accompanying doubts and sadnesses and worries. This is exactly the aura conveyed by the album’s cover. On it, Wainwright’s shiny coiffe of brown hair is both combed back and spilling forward; his features are so pronounced and his lips so dark as to be rouged. He hangs his head in profile, in apparently some mixture of remorse, shame and rumination. It is obviously a pose, but one with an earnest bearing to it. It’s perfect for an album that aims to address such a wide scope, an ambition that elevates it from being a collection of songs to being a social document. It is a break-up album and a coming-of-age album and a work of singer-songwriter angst and then some; it encompasses a vast landscape of feeling.

And what of New York? With the tumult-ridden year we’ve had, there’s a similar blend of melancholy and hopefulness these days. New York seems very much like the former Beale home that Wainwright recasts in “Grey Gardens”: it is a partly abandoned, partly occupied playground, gnarled and labyrinthine but possessed of a simultaneously diverting and unsettling atmosphere. The cliques of New York are as segmented as ever, but there also seems to be a shared sympathy about this, as if we are all aware that the scene is fraught but that we must be resilient. We’re like “Cigarettes and Chocolate Milk,” which not only begins Poses but ends it in a slightly peppier reprise. Wainwright was saying that every period has its challenging foil, that we exist between times of fulfillment and frustration. Put this album on and marvel at its still ferocious presence, its moments of clarity, apology, and romanticism. The deep in which it rolls, as it were, continues to stun.

Rakesh Satyal is the author of the Lambda Award-winning novel Blue Boy. He also sings a popular cabaret show in New York, an installment of which was “Roofies: The Songs of Rufus Wainwright and Fiona Apple.” Photo by Ben Beaumont-Thomas.

Some New Directions

by Thomas Beller

Lou Reed wore black. He moved slowly and a bit stiffly through the darkness that had descended on the Great Hall, a sheaf of paper in his hand. For the last thirty years he has looked like an ageless lizard but now I felt concern for him at the sight of his stiff gait. He entered the circle of light and put on reading glasses, gold rimmed.

Just a few minutes earlier the audience had been treated to several facts. One of them, shared by the Dean of Cooper Union, was that Abraham Lincoln had spoken in this very hall. I have been to a number of events at the Great Hall over the years and this fact has been reported on every occasion. The space — a scooped out amphitheater underground, slightly redolent of a bunker, with a domed ceiling and gothic arches — resonates with the evocation of Lincoln’s speech having been spoken into darkness over and over for decades, centuries. The other fact was that although the program listed him later in the evening, Lou Reed would now go first because of another commitment. Immediately I began to imagine what this commitment might be, if it was another public appearance, or a dinner with a friend, or some complicated mélange of professional and personal socializing, or if he was just tired and wanted to go home and watch TV. At any rate it was going to be an evening of circling around and engaging with the avant-garde, and Lou Reed was a fine ambassador for this world, whose literary iteration has always made me feel a bit uncomfortable, even reproached. I was one of the presenters that evening, so in this encounter I felt somewhat beyond reproach. I was eager to see how it would all look when freed from the defensive position.

Reed began to read “In Dreams Begin Responsibilities,” by Delmore Schwartz. Behind him were three huge screens which were now filled with a photograph of Schwartz, dapper in a suit and tie, luscious full lips and no sign of the madness that was to undermine him. The mood of the moment was that of the early minutes of an art house film, black and white, scratchy and intense — an analog atmosphere. I half expected to see a credit for Janus Films or New Yorker Films appear followed by the somber opening shot of something from Goddard, De Sica, Jarmusch.

Maybe I felt this because “In Dreams Begins Responsibilities,” itself takes place in a movie theater. The narrator settles in to watch a film of his parents’ life before he was born. Scenes from a courtship, with commentary from its offspring.

Of all the material in the New Directions catalogue, whose 75 years we had gathered to celebrate, and which includes such familiar names as Ezra Pound, Borges, Henry Miller, William Carlos Williams, Roberto Bolano, and Tomas Tranströmer (who just won the Nobel prize), this book by Delmore Schwartz, and in particular this story, is the one with which I am most familiar.

Reed read in his monochrome Long Island accent. The sound system was excellent. His tone was conversational, matter of fact, pitched just a little towards tension. We sat in the dark watching Reed in his pool of white light at the podium, hearing about a man sitting in the darkness watching bright images on the screen. The movie theater, and the movie, are set in New York City.

You are also welcome to read this later with Instapaper.

Somewhere along the line the American avant-garde in literature moved back into the America from which it traditionally fled; nestling in academia, or just in cities with low rent. Dalkey Archive Press, located in Champaign, Illinois, is just the most conspicuous example. Large parts of its catalog are crusty New Yorkers like David Markson, who lived in a studio in the West Village, and Gilbert Sorrentino, who did his time in California but came home to Sheepshead Bay to die, and Carole Maso, now a country matron but for a long time a bohemian who made rent by cleaning Manhattan office buildings at night. Listening to Reed’s voice, remembering the voice of Irving Howe, and imagining the voice of Delmore Schwartz, was an affirmation that the avant-garde had once had a distinctly New York address.

Reed’s hands trembled a little as he turned the pages. His rendition may have deprived the story of some its humor but he brought other things to it, most notably a sense of place. That accent! On the early Velvet Underground records it is not so noticeable, in the same way that when I was a kid and listened the Beatles I assumed they were American; when I first heard them speaking it was a shock. In Reed’s later, solo work, his singing becomes a kind of declaiming and he comes out of the vocal closet as a New Yorker, specifically a guy from the boroughs — even if he is from Long Island — someone familiar with “the Dirty Blvd.”

I started thinking of how many of Andy Warhol’s Factory gang were outer borough people — Reed; Mapplethorpe with his hard core Queens accent and Patti Smith with her New Jersey sound; Paul Morrissey, who made the movies, and Donald Lyons, who wrote about them and was Edie Sedgwick’s muse, from the Bronx and Queens respectively, as was Danny Fields, who managed the Velvet Underground and brought Sedgwick into Warhol’s circle.

Now the screen behind Reed featured the cover of the book itself, edited by James Atlas and with an introduction by Irving Howe. Reed’s voice was like a conduit to an earlier New York, a place of immigrant striving that was directly engaged with literature and politics in a way that feels abstract now, that incredible gang of Jewish Intellectuals; Schwartz, Irving Howe, Daniel Bell, Irving Kristol, Norman Podhoretz.

The payoff of “In Dreams Begin Responsibilities” (spoiler alert) is when, at a key moment, the interior voice we have been listening to suddenly surfaces and he begins shouting at the screen. “Don’t do it!” he yells. “It’s not too late to change your minds!”

I thought Reed did this well but I also felt he had sold some humor or dynamic in it a bit short. But then the story continues to a place I had forgotten about — an usher grabs the narrator’s arm and throws him out of the theater, all the while delivering a lecture on the perils of acting crazy, how the narrator is too old to behave like this, doesn’t he know that? “Everything you do matters too much!” says the usher.

Reed made that usher come alive. He left the pool of light to applause. It was, by far, the lengthiest presentation of the night, appropriately. Reed was Schwartz’s student at Syracuse, and is writing an introduction to a new edition of the book.

Nicole Krauss, in dangling gold earrings, came next, a solemn presence. She talked about her special bookshelf where she keeps her most extra favorite books — only a slight paraphrase — and what a large number of them are from New Directions. She read from the work of Yoel Hoffmann. He was an author, I decided snappishly, whose obscurity seemed justified.

There was one vivid image — a carp that had been caught in the sea is brought home and put in a bathtub. It swims back and forth for two days, up and down, and then the Aunt in the story, its main character, declares, “That fish thinks just like us,” and insists it be brought back to the ocean and set free. Hoffmann was one of several authors I was introduced to that night who possessed the distinction of not eliciting my interest. (Though having now slandered this guy, and by extension Krauss, I will now probably feel guilty and therefore develop an attachment to him; I will have to read him to justify or overturn this blithe assessment.)

Paul Auster appeared in triptych on the giant screen, sitting in his study on a grey-green leather couch, hair combed back neatly over his head. Another New Jersey kid, you can hear it at the edges of his voice, he began with an encomium to New Directions in general and then began talking about George Oppen, a poet. He read a striking piece of prose about the predicament of men who wished to avoid the German draft during World War II and who “dug a hole.” In this hole they lived for up to two or three years. Winter was a problem, not for the cold but because anyone who delivered food to the hole in the snow would leave tracks. The only safe time to deliver food was during snowfall. One man knew of the locations of a couple of dozen such holes and kept these men alive. But he had his own problems, which the story — could it have been a poem that Auster read as prose? — goes on about in fascinating detail.

I had expected the flatness of the screen to make Auster’s appearance dull, but there was an entirely unexpected and exciting aspect to it — we sitting, like a special guest, with Auster in the confines of his study. His place of work, procrastination, sex, or sexual thoughts, a private, interior space which was filled with books and pictures and other personal ephemera. I could not make out the titles of the books but their shape, color and texture were interesting — quite a few old bound items were part of a set, a number of these sets of two or three or four. The collected works of someone; not knowing who was almost as interesting as knowing. Framed pictures hung on the wall and also sat on his desk, leaning against the back wall, in black frames. It was a veritable Elle Décor sort of moment, and I thought of all the exasperating moments in movies and fashion shoots when someone gets it into their head that books would be useful as a prop, and how shamefully fake these moments are; the apotheosis of this being, perhaps, the lobby of the Mercer Hotel with its huge bank of books that, upon being touched, reveal themselves to be made of styrofoam.

Auster, perhaps trained by his years of Francophillia, has very nice taste. Over his left shoulder was a photograph of an attractive, stylish woman who I assumed was his wife. Though it could also be his daughter, the one he wrote about saving when she fell down the staircase and he happened to be there to catch her.

Part of me felt like I was intruding, but then Auster made his name with the New York Trilogy, books about highly stylized voyeurs, and his high minded fans often get all Rear Window on him, most famously the tourist from Turkey whose peripatetic stalking of Park Slope in search of the author was documented in the New Yorker. I am sure he has had to deal with less charming instances of this impulse. The rap on Auster, in my opinion, is that his voice, on the page, sometimes veers into Rod Serling territory. Once you enter the Twilight Zone it is hard to leave. But I could have sat with him in his study for hours listening to him read and talk about George Oppen.

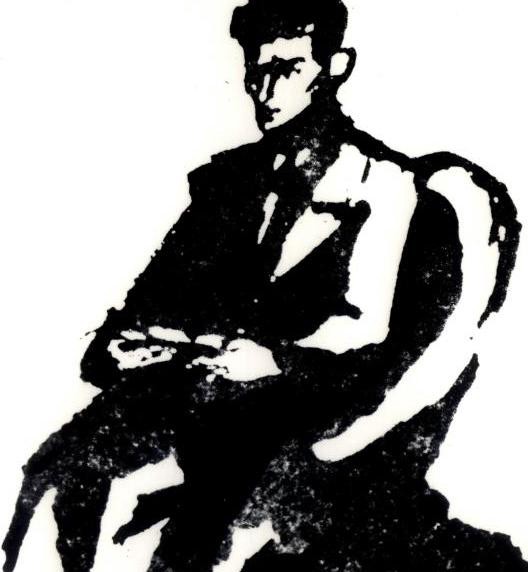

Francine Prose was the first reader to make us laugh — behind her the screen filled up with the book cover of Gustav Janouch’s Conversations with Kafka. A work of non-fiction, Janouch, an aspiring writer, had a connected father who arranged for him to take long walks with Kafka through Prague. Kafka did most of the talking. At the end of these evenings Janouch would rush home and write everything down. Prose shared the following anecdote from the book: The two men are walking at night when they see, off in the distance, a dog cross the street.

“What was that?” says Kafka.

“A dog,” says Janouch.

“It could be a dog, or it could be a sign,” Kafka says. “We Jews often make tragic mistakes.”

The book’s jacket was up on the screen, a painting of a young Kafka against a bright yellow background, his expression handsome, astute, avid, almost leering. I felt a materialistic, acquisitive response to a book based on the design alone. Going all the way back to the stark minimal design of Ezra Pound and Djuna Barnes, New Directions has always had a flair for design but it’s tended to be black and white.

Prose talked about how, in lieu of cash, she took a gift of books as payment for her intro to the Janouch book, and finally settled on Microtexts by Robert Walser, page after page of tiny scrawl and fascinating design. Walser, as literary as can be, was mimicking the impulse of every ambitious art director I have encountered at a magazine, namely to make the font so tiny that the words are like conceptual decorations to the page whose main purpose is to make the white space look dramatic. It was a gorgeous book. New Directions have clearly staked their future on the fetishized physical object, one whose tactile pleasure correlates with its literary pleasure.

It occurs to me now, writing about Prose, and knowing her prolific work as author and journalist and literary activist, that her name could be a stage name, like Robert Zimmerman changing his name to mimic Dylan Thomas, whose voice had kicked off the evening.

Rackstraw Downes came next. He announced he had been reading New Directions for forty years and read from Eliot Weinberger. Somehow, perhaps because I was mulling over the name Rackstraw Downes, I missed everything he said.

Carroll Baker came next. It was not a name I was familiar with. A lady of a certain age, she came to the podium with a bounce in her step, radiating sass and good humor. She had short blond hair and pink sweater and announced that she would be reading from Tennessee Williams’ Sweet Bird of Youth. A still from the film appeared behind her in triptych. It featured a young woman who resembled Carroll Baker, in a mode of astonishingly sultry suggestiveness, curled in the arms of a man.

It took a moment to grasp that we were now being presented with two versions of the same person. I looked back at Carroll Baker, hoping to God that I wouldn’t think “I can’t believe that is the same person.” I didn’t think it; just the opposite, it was very much the same person and she stood at the podium a bit mischievously, as though somehow aware of this trick and our anxiety at what judgments we might arrive at. It was interesting to subsequently discover that her first job in show business was as a magician’s assistant.

Baker launched into a scene. We were in the hands of a performer and I was impressed by the reading, the posture, the scene, and the fact that while reading she chewed gum.

Also, I was very impressed that she wore no make-up, at least none that I could detect. The image behind her was replaced with the cover of the book, but that black and white still remained — a retinal burn that lasted all the way until she laughingly strode back to her seat to the sound of applause.

The poet Anne Carson’s presentation was listed on the program as including dancers and a saxophonist. The dancers were on film; they moved around a large spooky space followed by a kind of Zamboni with a spotlight gliding after them. The saxophonist was real, and stood behind her on stage, breathing sounds of accompaniment that were at times musical and at other times a sort of sound effect. She read from a book of poems about her brother, written after his death. The book, Nox, is based on a poem of Catallus, “Poem 101.” One word of the Catallus poem surfaces in each of her poems. She read the Catallus poem in Latin to start. Before the dancers appeared, a black and white still of a young boy popped up on the screens, her brother, “looking heroic in flippers.” She said. The picture itself only gave us a young boy, maybe thirteen, maybe ten, and the feeling of time lost, but beyond that it drove home that we were now going to be presented with an artful and intense processing of grief. I was riveted throughout, even in the really arty bits when the sax made funny noises, thinking that it was so great to see this in New York, in downtown Manhattan, in the Great Hall, which validated it somehow, as though here in New York you can do this, it is what people come here to do, even if they then disperse to university towns. Here, in this bunker, is where the oxygen is. I don’t know what Abraham Lincoln would have made of it all, the saxophone, the dancing singers, the slender woman at the podium. He may have been a big fan of Catallus. He may have understood the poem she read in Latin and not had to wait until the end when she read it again in English, revealing it to be about the loss of a brother. Perhaps he would have felt comfortable with its intense sense of loss and grief.

I made a mental note to read Catallus.

Fredric Tuten came next, and read from Djuna Barnes’ Nightwood, praising it even while saying it was at times a very difficult book to read, which I was heartened to hear, as I have never gotten very far in it. He then joked that he was tempted to read all of it. He laughed heartily at this suggestion. In me it instilled a moment of fear. Not that I thought he would do it, though you never know.

He told us how, after she moved back from Paris, Barnes lived in a tiny rent controlled apartment on Patchin Place, just behind the church at Sixth Avenue and Greenwich Avenue, until she died. Tuten told us her neighbor, E.E. Cummings, used to drop in regularly to see if she was okay. What stayed with me most from Tuten’s appearance was how, when he characterized Nightwood as a book about love, I felt no spike of interest, but when he said that it was also a book about the intense feelings of love rejected, I was interested.

Next was a short clip from the movie The Driver’s Seat, based on a novel of the same name by Muriel Spark. A parenthetical at the start informed us that Muriel Spark hated the movie; I later found out Spark was never paid for the rights, though whether this informed her opinion of it is hard to say.

The clip was deeply strange and wonderful in a kitschy 1974 sort of way: Elizabeth Taylor appears on screen in close up, furious; she is buying a dress, not in a store but in a showroom. She moves among mannequins, her eyebrows splendidly dark and alive; she is talking about the importance of natural color, natural fabric. The saleswoman she speaks to is Italian. The whole scene feels dubbed. When it is revealed that the dress is stain resistant, Taylor throws a hissy fit, storms into a dressing room behind a curtain, and tears off the dress. A moment later a more senior figure emerges to placate the angry Taylor. A flustered little dynamic ensues. The younger saleswoman tries to explain. Then Taylor steps from behind the curtain and there is a shocking moment of confusion provoked by the flesh-colored bra she is wearing. In the end it turns out the same dress is made without the stain-resistant chemical. The scene ends there. The heads of the mannequins between which Taylor has been moving are wrapped in tin foil.

I was next. I talked about a remark by James Laughlin, the founder of New Directions, about how their publishing strategy is built around the notion that a book takes twenty years to find its audience. Of course this is an utterly outrageous statement, wonderfully contrary, and possibly true. It echoes the famously amusing statement by Zhou Enlai, when asked by Henry Kissinger about his thoughts on the French Revolution: “It’s too early to say.”

A less provocative version of Laughlin’s remark is that readers have strange and peculiar needs. Their wishes are often perverse. It’s more complicated than supply and demand alone. Books sit for years on our bookshelves, mute and ignored, and then one day they call out. Maybe you take them down. Or maybe you just glance at them. And there it may end. Such a process may have to occur several times over a period of years before the book is even opened. But one day you suddenly think you absolutely must read this book. You may feel this at the exact moment you are unable to get to that book, at which point you buy another copy of a book you have spent twenty years not reading. At which point the fever may pass again, never to return. Or you may actually read it at last.

The New Directions author I spoke about was Niccolo Tucci, whose collection of stories, “The Rain Came Last and Other Stories,” is a favorite of mine. Part of the charm of his stories is their capriciousness. By way of illustrating the strangeness of a reader’s needs and desires, neither of which this reader is in particular control of, I spoke of how a month or so earlier I was in the manuscripts and archives division of the New York Public Library, perusing the letters and manuscripts of Niccolo Tucci, shortly before leaving on a trip to Cambodia. I had been to Cambodia before; I was going on assignment for a magazine; I had a lot to prepare for in the two days before my flight. There was absolutely no reason in the world I should have been spending time perusing marginalia by Niccolo Tucci. But there I was.

Tucci’s stories are histrionic, droll, charming, seductive, chaste in their concern for family life yet somehow acknowledging the ever-present libidinal chaos that springs from it — his voice has a naughty, Italian, libertine lilt. His letters are more extreme versions of this. The self pity is less comic and more urgent. I found them shockingly hysterical, in both senses.

I began by reading a letter written to him by an editor at the New Yorker, Katharine White, dated September 5th, 1947. It begins:

“Dear Mr. Tucci,

“I am sorry that you are having such a hard time writing but perhaps it will reassure you to know that what is happening to you is happening to dozens of other writers, my husband among them. He had not been able to work all summer and indeed has written less than you have, I know, since the first of the year. The awful state of the world is what makes a thinking and imaginative person half sick all the time.”

Then I read the letter to which she was responding:

“Dear Mrs White,

I should have answered your very kind letter long ago, but I was always hoping to send you a few stories as the best substitute for an answer. I have them: they are summer stories, and in a few weeks they will no longer prove acceptable. And I also have every other reason in the world to try and sell them now; among others the fact that I have borrowed money from the magazine and cannot pay it back. Yet I would be so grateful to you or to anyone else if anyone could tell me what it means when a man my age, with the problems he has and the wonderful opportunities that are offered him by magazines like yours, cannot even overcome the reluctance to get a few things copied and sent away by mail. I am now finishing a reporter at large on Einstein whom I visited recently with Bimba and my mother-in-law (who is also on my shoulders now). Einstein said many things that were quote interesting, then he played the violin for Bimba, so these are all things I could quite easily write down and give to Mr Shorn [sic]. But it will take me another week to do it. It’s not the heat, and not the family. They are away, in an abandoned farmhouse of the Addams type, near Harpers Ferry in Millwood Virginia. I am here alone, surrounded by my manuscripts. No one disturbs me except the world at large and the impending war, and of course the futility of all appeals to reason. This goes for me too. I appeal to my reason and nothing happens. Really, I am almost ashamed to show my face at the New Yorker now. Well, probably today, after mailing this letter, something will happen and I’ll work.

“Remember me with friendship to Mr White, please.

(then in a fountain pen scrawl): “Yours with best regards Nika Tucci”

From there I launched into a few paragraphs of his story, “The Evolution of Knowledge.”

After that I stepped off but not before adding, “It’s very difficult, and rare, for a publisher to be interesting, even for a short time. And New Directions has been interesting for a long time.”

This was my nod to the fact that a publishing house, if it lasts long enough, is not a single entity but includes many hard to pin down issues of succession, education and, most ineffably, taste. The same taste that informs an editor as they read a manuscript comes into play when hiring people to surround and eventually succeed them. James Laughlin started New Directions, he published the iconic books on which its reputation rests, and somehow this sensibility was passed down from one person to another and ended up with Barbara Epler, who is now editor.

Helen DeWitt came next. Limpid blond bangs and blinking furiously like a subterranean creature forced into daylight. There was a lot of stammering, fumbling with the microphone, gasped phrases. “Standing up here is like being in Kafka’s The Trial!” she finally blurted out and, a moment later, “Oh, they’re clearing out.” Chunks of people were gathering their stuff and heading up the aisles. Something about her manner of incredulity and excitement gave every indication that we were about to be treated to a kind of high art version of Sally Field’s famous Oscar speech.

I don’t think that every writer needs to be a loquacious figure of ease who is never happier than when her voice is amplified to a room, but all this stammering and blushing seemed a bit much. Then I considered that DeWitt was not just promoting a New Directions author; she was herself a New Directions author, whose novel, Lightning Rods, has just been published. These publication readings are, in my own experience, occasions for a mini-nervous breakdowns. They are supposed to be a celebration of the book’s publication, but for the writer, especially once you are past your first one when you and the book are pure potential and all your friends are there, they are going away parties, a kind of a wake; I wore all white at the first reading at Barnes and Noble for my most recent book. It was the end of summer; I hadn’t thought about it too much. But in hindsight it corresponded to my feeling that the reading was a kind of Buddhist mourning ritual in which the body is burned so the soul can roam free.

DeWitt, after citing the number of rejections her manuscript endured before New Directions took it (19), did get around to reading and talking about a New Directions author, Ezra Pound. Pound, she said, had been domesticated and made into a harmless pet at the college she attended, Smith. This so aggrieved her that she dropped out to live a life of hardship and adventure and become the person she is. She hammered at Smith College for a while and then at all English departments before pausing to say, “I mean, yay, English!” It was impressive, the hate. Then she read from Ezra Pound’s Cantos.

Next came Siri Hustvedt, who appeared on the screen seated on the same couch as her husband, Paul Auster, but at the other end, so we had the satisfaction of further exploring the room and its decor. Behind her was that photograph of herself, I think, her arms wrapped around her torso. But after a minute the video malfunctioned.

Next up was Paul Beatty. A big guy, lean but with some heft, he approached the podium with a curious body language that reminded me of that slippery quality certain boxers have, a bob and weave. He read from Roberto Bolano’s “Distant Star.” But first he talked a bit about New Directions books, and how he had always tried to avoid them. “They’d say, ‘Oh, you’re from L.A., you have to read Nathanael West!’ And I’d be like, ‘No! I don’t want to! I always hear about him. But then I’d have the book, and read it, and I’d have to wrestle with it.”

Francisco Goldman read last. He spoke of how New Directions had been a boon to his early adventures in picking up girls when he lived in Boston, and how they were the first books he ever purchased. He read from the work of César Aira, a prolific Argentinian author whose method, Goldman told us, was to sit down and just start writing until the book was done. “Don’t try this at home,” Goldman said. “Unless you have this particular kind of genius.” Goldman read from a book called An Episode in the Life of a Landscape Painter.

The evening wrapped up with Alice Quinn, head of the Poetry Foundation of America, who presented Barbara Epler with a black and white photograph of James Laughlin. He is seen in silhouette, smoking a pipe, a bit mysterious, even a little bit Hitchcockian somehow. Quinn was for many years poetry editor at the New Yorker, and she published some of the poems that Laughlin had begun writing in his later years. She told of a visit to his Connecticut home where, for lunch, she received an immaculate grilled cheese sandwich and Oreo cookies for dessert. Though this was reported in all innocence I took from it the feeling that Laughlin was an old school WASP who did something adventurous and meaningful with his money.

But that is a kind of praise as Percocet — it kills feeling and clogs you. Beatty’s remarks were the most memorable for me, because they acknowledged what a pain in the ass literature can be. Speaking about New Directions Books, with feints and ducks, he spoke of books not as some wonderful palliative, not as this delightful thing that can move and uplift us, etc., etc., but as frightening, demanding, intimidating and essentially bullying presences. Things he would often prefer to avoid. It was a bit like the feeling Italo Calvino evokes at the start of If On A Winter’s Night A Traveler, when he talks about a writer going into a bookstore and being besieged by all the books he hasn’t read but means to, or hasn’t read but ought to, all of them reproaching him.

In Calvino’s warm, Italian voice it has a humorous quality, but Beattie seemed to say that these books — specifically these New Directions titles that people kept giving him — were a pain in the ass that took him out of his own groove. “It happened with Bolano,” he said. “Everyone was going on about The Savage Detectives. The last thing I wanted to do was to read anything by Roberto Bolano. But someone gave me Distant Star. And so I had to wrestle with it.”

The evening was filled with challenging moments, but the whole time, even in the moments of resistance or boredom, I was awake in some essential way, which is why I was so eager to write this down this account of it. I wanted to get these thoughts down on paper, so to speak, before they vanished like fireflies whose beauty was connected to a specific time and place.

Thomas Beller is a cofounder of Open City. He teaches writing at Tulane University, and his most recent books are The Sleep-Over Artist, a novel, and How To Be A Man: Scenes From a Protracted Boyhood, an essay collection.

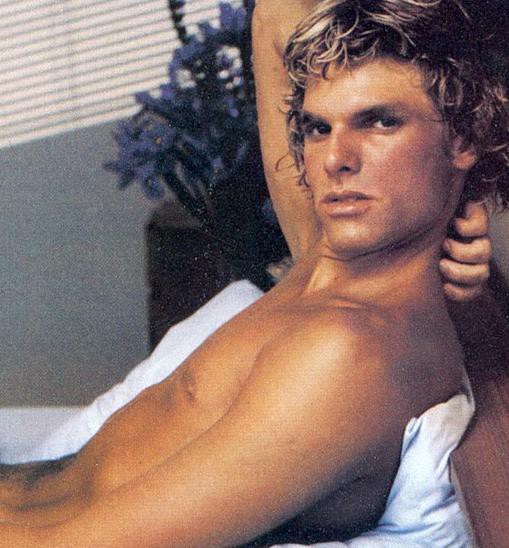

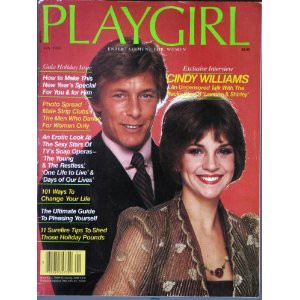

Playgirl's First Hardon

by Jessanne Collins

January 1980. A nation nurses a sepia-hued hangover. It’s the dawn of a new decade, and while the polyester may not be packed away just yet, change is in the air. For the first time in history, there’s an erection in the pages of a glossy magazine.

Playgirl is eight years old and boasts a circulation of 10 million. It’s clearly hit some kind of cultural nail on the head, borrowing Playboy’s patented aspirational hedonism and appropriating it for the fun ’n’ flirty feminist set. This month, the centerfold is a sun-kissed California blonde named Geoff Minger. He reclines, shinily, on a set of clean white sheets. In one shot — in pointed contrast to the afternoon light on the drawn venetian blinds, the purple flowers on the bedside table — his penis just stands there, like, yeah?

It’s not like the late ’70s were some kind of disco Camelot, but there was something kind of soft-focus about them. Jimmy Carter was president, cigarettes were mainstream, air travel was exotic, and for another year or so anyway, sex wasn’t gonna kill you. It’s like I overheard this lady say yesterday, apropos of a Thelma Houston song playing at a cafe: “Everybody was just so beautiful in the ‘70s! Everything was so shiny and sparkly!” And there’d been plenty of penises in Playgirl’s pages, since its second issue, in the summer of 1973 (readers had complained when there were none in the debut), sandwiched softly between ads for Summer’s Eve and fashion spreads flowing with macrame.

But a full erection! That was something else. Something deliberate, something direct. “From the beginnings of Western civilization the penis was more than a body part,” David M. Friedman writes in his 2001 cultural history of the organ, A Mind of Its Own. “It was an idea, a conceptual but flesh-and-blood gauge of man’s place in the world…. It is possible to identify the key moments in Western history when a new idea of the penis addressed the larger mystery of man’s relationship with it and changed forever the way that organ was conceived of and put to use.”

So how better to greet this particular new decade than with a (sorry) stiff salute? By this time next year, John Lennon would be dead and Ronald Reagan on his way into the White House. Shoulder pads and neon colors are coming down the runway, and soon to be sporting them, a new archetype: the busy career woman, slinging a diaper bag in four-inch pumps. She’ll still be making a fraction of what her male colleagues bring home, though, and with all the domestic labor on her to-do list, she’ll have less time and patience for fantasy and romance and nonsense. The era of chiffon and divans is over.

In its way, Playgirl, in attempting to define and capitalize upon woman’s ever-shifting “place in the world,” changed again the way the organ was conceived of and put to use. Hear that distant synth beat? Madonna is coming. Samantha Jones is at her heels. It’s hard to imagine either of them, or anything that came next, in a society where women and men, in theory anyway, weren’t equal-opportunity oglers.

Jessanne Collins is an editor at Mental Floss and the coproprietor of Finite + Flammable.

Each Generation Has Found They Have Got Their Own Kind of Sound

Each Generation Has Found They Have Got Their Own Kind of Sound

by Daniel D’Addario

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aYywiQ3-6To

Rumors have circulated that Madonna, recording artist, will sing with M.I.A. at the Super Bowl. Nicki Minaj is also implicated. Both artists have had success, but can either bring back the monoculture? Leaving the fleeting sensation of a Lynn Hirschberg truffle-fry ambush aside, if M.I.A. were interviewed by Barbara Walters, who would care? Neither M.I.A., a self-consciously “edgy” singer of extraordinary gifts of curation, nor Nicki Minaj, a self-consciously outré rapper of extraordinary gifts full-stop, have cultivated personae beyond “hardworking,” “talented,” and (in M.I.A.’s case) “prone to ignorable political pronouncements.” It’ll be a good show, but no one should expect an iconic moment on par with Madonna heaving in a wedding gown or re-enacting Versailles to the tune of “Vogue.” Having marketable personality upon which to hang a moment is, now, left to those “famous-for-being-famous.”

Madonna’s last great moment, ever, of being famous-for-being-a-famous-singer (a category no longer in existence) was in 2003. Her performance at the VMAs ended with shared kisses with Britney Spears and Christina Aguilera, a performance viewed then as the bestowing of the Queen of Pop crown upon the two leading princesses and most easily viewed now as the dying gasp of the monoculture. Madonna’s Super Bowl gig feels rather like charity and she no longer has the pull to recruit whatever 2012’s pop princess manqués might truly be (Adele and Taylor Swift? Beyoncé and child? Lady Gaga and a Lady Gaga impersonator?); Christina Aguilera is a tippling, toppling reality-TV Miss Havisham; Britney resurfaced this year for a zombified album and a guest spot on a single by Rihanna, which even Rihanna’s devoted fans, resilient as they are, can view as a comedown. The road from the early 2000s to the early 2010s, from ménage to Minaj, has treated none of the once world-beating trio well.